Dear Editors,

Sensitization leads to the formation of antibodies to human leukocyte antigens (HLA) [1]. Among sensitized heart transplant (HT) candidates, the waiting time for HT is longer along with the risk of adverse events [2]. Moreover, the presence of HLA antibodies reduces rate of survival and increases the risk of rejection and cardiac allograft vasculopathy [3].

These rejection episodes require increased immunosuppression, which in turn raises concerns about adverse effects such as malignancies. Moreover, desensitization, including intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), plasmapheresis, and several anti-humoral agents, is performed for highly sensitized patients for an increase in the chances of a negative crossmatch, expansion of the donor pool, and improvement of post-HT outcomes.

However, the relationship between sensitization and post-transplant malignancies (PTM) has not been well understood. Therefore, we investigated the incidence of PTM and the impact of desensitization for PTM in sensitized HT recipients.

This study design is illustrated in Supplementary Figure S1. We reviewed the records of adult patients who underwent HT between 2010 and 2023 and excluded those with a history of malignancies and missing data. Sensitization was defined as a panel-reactive antibody (PRA) level (either class I or II) of ≥10%. Highly sensitized patients were considered for desensitization therapy. Desensitization included Rituximab, Eculizumab, Bortezomib, Tocilizumab and Obinutuzumab treatment. Our institutional protocol for post-transplant management has been previously described [4, 5].

The primary endpoint of this study was the incidence of PTM diagnosed based on histological evidence. The secondary end point was all-cause mortality. The study participants were followed up until 31 August 2024. Event-free survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazard model was constructed, adjusting for sensitization status, age, and sex. Nearest-neighbor propensity matching was performed to generate matched cohort. The propensity score model was developed using the following covariates: recipient age, sex, and history of HT. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cedars-Sinai. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Among the 1,096 patients who underwent HT, 364 were sensitized and 110 were desensitized. The overall mean age was 55.1 ± 12.9 years, and 801 (73.1%) patients were male. The mean follow-up period was 6.4 ± 3.8 years.

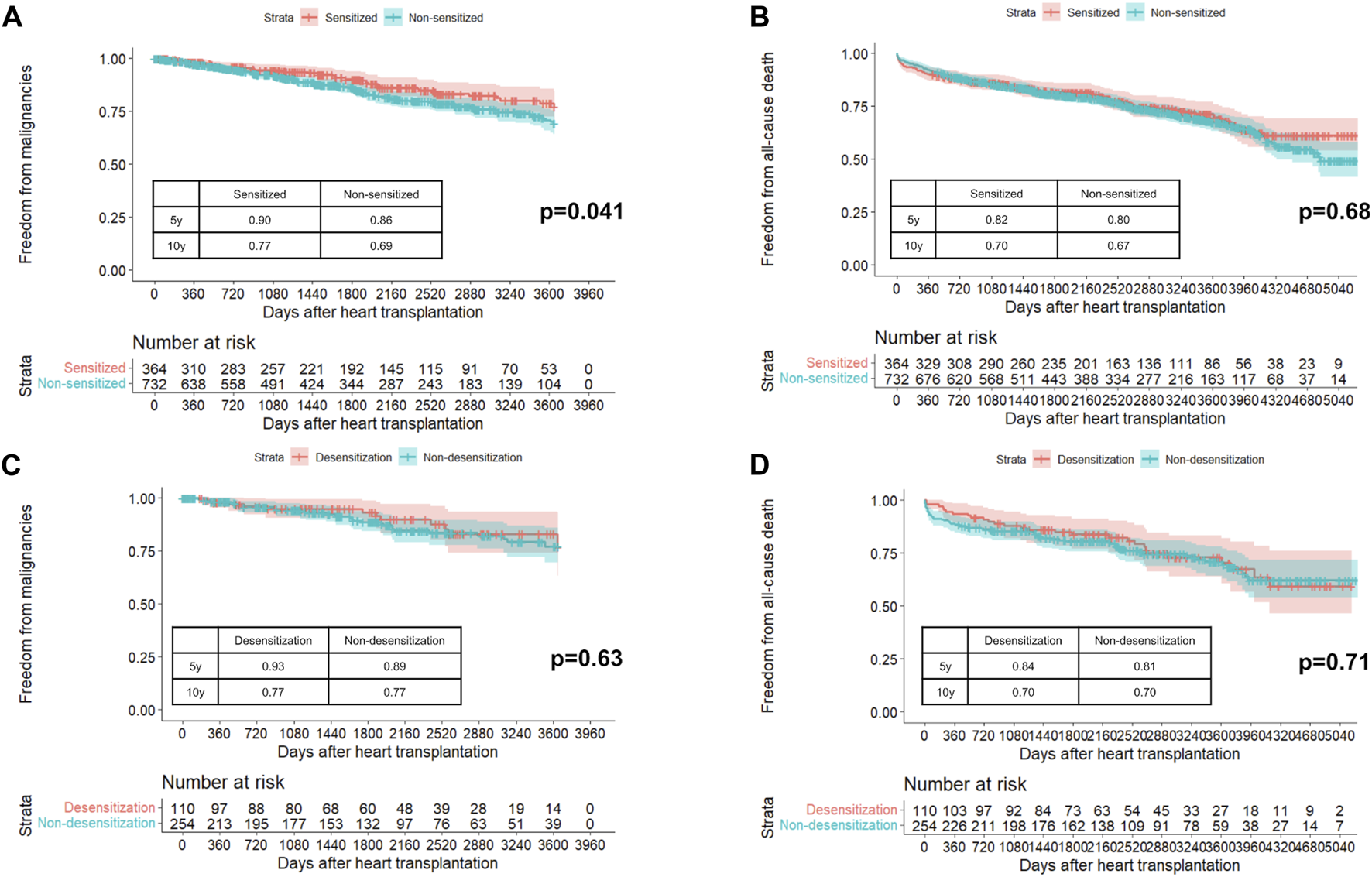

The baseline patient characteristics of the sensitized and non-sensitized groups are presented in Supplementary Table S1. The sensitized group was significantly younger, with a higher proportion of female, history of pregnancy, history of blood transfusion, history of HT, and sex mismatch than the non-sensitized group. The mean follow-up period was 6.5 ± 3.9 years in the sensitized group and 6.4 ± 3.8 years in the non-sensitized group (p = 0.68). During the follow-up period, 183 (16.7%) patients developed PTM, with skin cancer being the most common, followed by genitourinary/gynecologic/renal cancers (Supplementary Table S2). Figure 1A shows the difference in freedom from PTM, which was significant between the sensitized and non-sensitized groups (p = 0.041). The 10-year freedom from PTM was 77% in the sensitized group and 69% in the non-sensitized group. However, the all-cause mortality was similar between the two groups (p = 0.68, Figure 1B). In the multivariable Cox analysis, sensitized status was not associated with PTM (Supplementary Table S3).

FIGURE 1

Probability of freedom from post-transplant malignancies (A) and all-cause death (B) in sensitized and non-sensitized groups. Probability of freedom from post-transplant malignancies (C) and all-cause death (D) in desensitization and non-desensitization groups in unmatched cohort.

The baseline patient characteristics of the desensitization and non-desensitization groups are presented in Supplementary Table S4. Before propensity score matching, the desensitization group was younger, had a higher proportion of females, and had a higher body mass index. The peak PRA value was significantly higher in the desensitization group than in the non-desensitization group. The most common agent for desensitization was rituximab (56.4%) followed by eculizumab (38.2%). The mean follow-up period was 6.9 ± 3.7 years in the desensitization group and 6.4 ± 3.9 years in the non-desensitization group (p = 0.31). In the unmatched cohort, freedom from PTM (Figure 1C) and all-cause mortality (Figure 1D) were similar between the two groups (p = 0.63 and p = 0.71). After propensity matching with one-to-one pairs, 108 patients in the desensitization group had a higher proportion of multi-organ transplants, whereas age, sex, and body mass index were similar (Supplementary Table S4). In the matched cohort, PTM incidence (Supplementary Figure S2A) and all-cause death (Supplementary Figure S2B) were comparable between the two groups (p = 0.43 and p = 0.58, respectively).

In this study, we identified the following: (1) Sensitized patients were younger, more often female, and had a history of pregnancy, blood transfusion, or HT. (2) The incidence of PTM in sensitized patients was lower than that in non-sensitized patients. (3) Desensitization did not lead to the development of PTM in sensitized patients.

Risk factors for sensitization include prior pregnancy, blood transfusions, infections, presence of homografts/allografts, and use of temporary or durable mechanical circulatory support [3]. Data from the United Network of Organ Sharing dataset for bridge-to-transplant patients show that sensitized patients tend to be younger and female [6]. Conversely, the risk factors for PTM, as identified in several large cohort analyses, include older age at HT, male sex, infection with oncogenic viruses, re-transplantation, and malignancies prior to HT. The risks of sensitization and PTM are inversely related to age and sex. The lower incidence of PTM in sensitized patients in our study might be explained by their younger age and higher proportion of females.

The safety of desensitization agents in terms of PTM risk is not well established, and reports on the association between desensitization and PTM in solid-organ transplants are limited. Bachelet, et al. found no difference in the incidence of PTM between sensitized kidney transplant recipients treated with Rituximab and those who were not [7]. On the contrary, a report from Taiwan showed that patients who underwent desensitization with Rituximab, plasmapheresis and IVIG in kidney transplant had a higher incidence of PTM, particularly urothelial carcinoma [8]. There are no reports on other desensitization agents beside Rituximab nor are there studies in HT population. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate desensitization and PTM in the field of HT and suggests no significant difference in PTM incidence between groups after adjusting for baseline characteristics.

This study has some limitations. First, this was a retrospective, single-center study with a small cohort. Second, IVIG and plasmapheresis were not defined as desensitization. The general categories of desensitization therapy include mechanical removal of antibodies, IVIG, and immunosuppressive agents targeting antibody production; however, this study focused on immunosuppressive agents targeting antibody production. Third, the targets of the humoral immune pathway for each agent used for desensitization were different, and further investigation of the PTM risk associated with each agent is necessary. Fourth, malignancy-related data, including stage and severity, were missing. Finally, oncogenic viral infections were not identified; therefore, their involvement remained unclear.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that neither sensitization nor desensitization therapies were associated with an increased incidence of PTM in this cohort; however, these results should be interpreted cautiously given the potential for residual confounding and the limitations of the retrospective design.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board of Cedars-Sinai. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Design of the work: MT and JK. Conduct of the work and data acquisition: MT, MK, DC, EK, AN, LS, ML, and JK. Data analysis and interpretation: MT, MK, DC, EK, AN, LS, ML, and JK. Drafting the work: MT. Reviewing the work and providing input: all authors. Final approval: all authors. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude California Heart Center research team members who enabled this long-term comprehensive study.

Conflict of interest

MT received a grant for studying overseas from Fukuda Foundation for Medical Technology and from Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research, outside the submitted work.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ti.2026.15593/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

PRA, panel-reactive antibody; HLA, human leukocyte antigens; HT, heart transplant; IVIG, intravenous immune globulin; PTM, post-transplant malignancies.

References

1.

KobashigawaJColvinMPotenaLDragunDCrespo-LeiroMGDelgadoJFet alThe Management of Antibodies in Heart Transplantation: An ISHLT Consensus Document. J Heart Lung Transpl (2018) 37:537–47. 10.1016/j.healun.2018.01.1291

2.

KransdorfEPKittlesonMMPatelJKPandoMJSteidleyDEKobashigawaJA. Calculated Panel-Reactive Antibody Predicts Outcomes on the Heart Transplant Waiting List. J Heart Lung Transpl (2017) 36:787–96. 10.1016/j.healun.2017.02.015

3.

ColvinMMCookJLChangPPHsuDTKiernanMSKobashigawaJAet alSensitization in Heart Transplantation: Emerging Knowledge: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation (2019) 139:e553–e78. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000598

4.

ChangDHYounJCDiliberoDPatelJKKobashigawaJA. Heart Transplant Immunosuppression Strategies at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Int J Heart Fail (2021) 3:15–30. 10.36628/ijhf.2020.0034

5.

DeFilippisEMKransdorfEPJaiswalAZhangXPatelJKobashigawaJAet alDetection and Management of HLA Sensitization in Candidates for Adult Heart Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl (2023) 42:409–22. 10.1016/j.healun.2022.12.019

6.

ArnaoutakisGJGeorgeTJKilicAWeissESRussellSDConteJVet alEffect of Sensitization in US Heart Transplant Recipients Bridged With a Ventricular Assist Device: Update in a Modern Cohort. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg (2011) 142:1236–45. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.07.019

7.

BacheletTVisentinJDavisPTatonBGuidicelliGKaminskiHet alThe Incidence of Post-Transplant Malignancies in Kidney Transplant Recipients Treated With Rituximab. Clin Transpl (2021) 35:e14171. 10.1111/ctr.14171

8.

YangCYLeeCYYehCCTsaiMK. Renal Transplantation Across the Donor-Specific Antibody Barrier: Graft Outcome and Cancer Risk After Desensitization Therapy. J Formos Med Assoc (2016) 115:426–33. 10.1016/j.jfma.2015.11.006

Summary

Keywords

cancer after transplant, desensitization, heart transplant, malignancy, sensitized

Citation

Tsuji M, Kittleson MM, Chang DH, Kransdorf EP, Nikolova AP, Stern LK, Lee M and Kobashigawa JA (2026) Due to Increased Immune Therapies, Are Sensitized Heart Transplant Recipients at Increased Risk for Malignancies?. Transpl. Int. 39:15593. doi: 10.3389/ti.2026.15593

Received

17 September 2025

Revised

06 December 2025

Accepted

19 January 2026

Published

29 January 2026

Volume

39 - 2026

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Tsuji, Kittleson, Chang, Kransdorf, Nikolova, Stern, Lee and Kobashigawa.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jon A. Kobashigawa, jon.kobashigawa@cshs.org

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.