Abstract

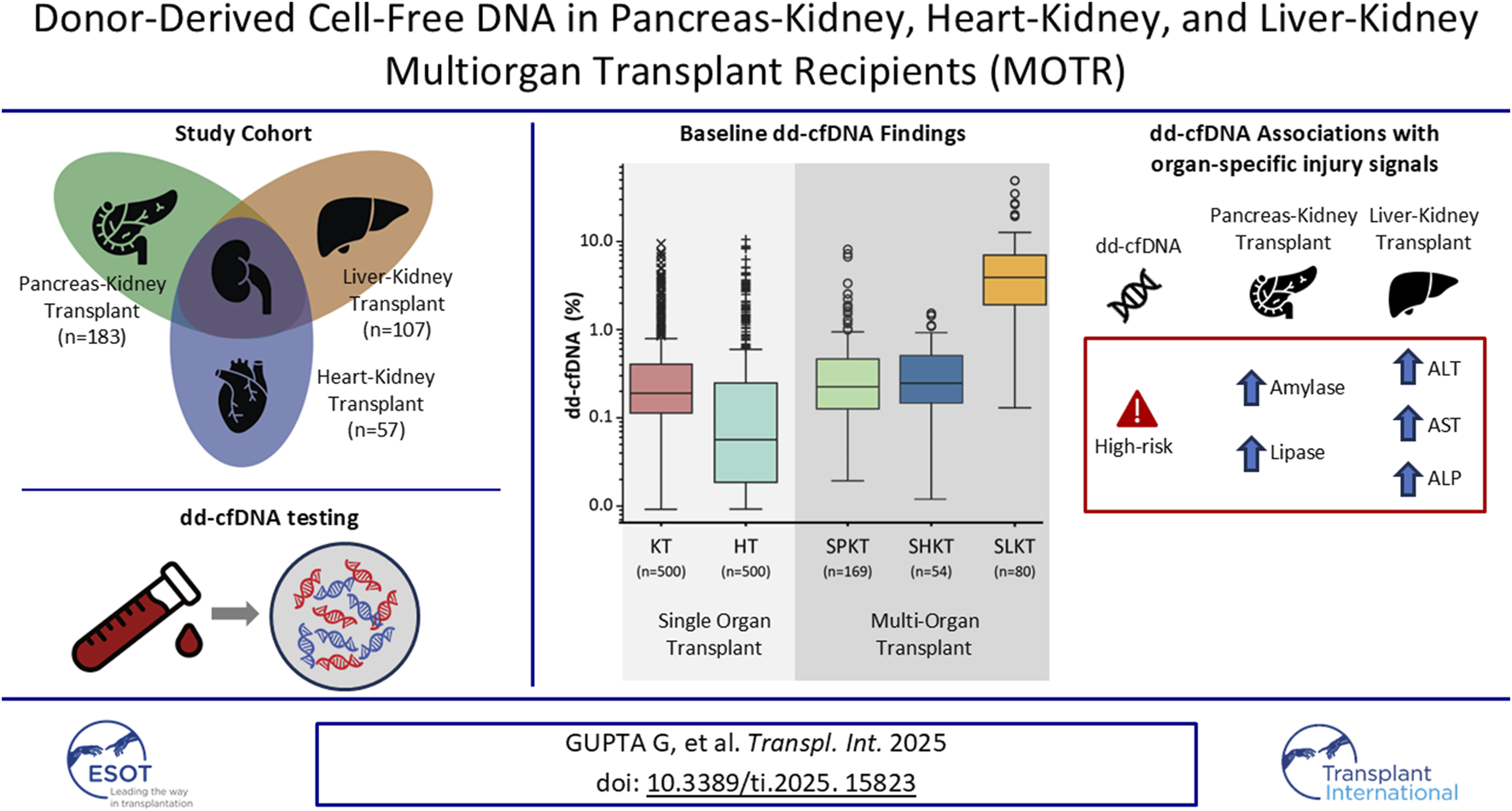

Donor-derived cell free DNA (dd-cfDNA) is an established biomarker for detection of rejection in single organ transplants; data is limited in multi-organ transplant (MOT) recipients. “Use of dd-cfDNA in Multi-Organ Transplant Recipients” (MOTR) was a multicenter, prospective, cross-sectional study that assessed dd-cfDNA fraction (%) and donor quantity score (DQS, cp/mL) in pancreas-kidney (PKT), heart-kidney (HKT), and liver-kidney (LKT) recipients. We explored dd-cfDNA baseline levels across the different organ combinations, and compared them to kidney-only (KT) and heart-only (HT) transplant recipients. Among 347 MOT recipients from 18 sites (PKT = 183, HKT = 57, LKT = 107), most (88.2%) had simultaneous transplants. Median dd-cfDNA levels in PKT and HKT recipients were not significantly different from KT; median dd-cfDNA levels among HKT recipients were significantly higher than in HT recipients (p < 0.001). In LKT recipients, median dd-cfDNA was significantly higher compared to KT (p < 0.001). dd-cfDNA showed associations with organ impairment indicated by abnormal values of pancreatic and liver enzymes in PKT and LKT. As the largest multi-center study to date evaluating dd-cfDNA levels in MOT recipients, MOTR showed that organ-specific physiology affects dd-cfDNA levels across organ transplant combinations, laying the foundation for future efforts to use dd-cfDNA to assess organ-specific signatures of allograft injury in MOT recipients.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Multi-organ transplantation (MOT) is an increasingly important therapeutic strategy driven by the rising burden of chronic disease, aging patient population, and the complex interplay of multi-organ dysfunction. As more patients present with concurrent multiple organ failure, MOT is the optimal treatment, providing life-saving intervention [1, 2]. The number of patients undergoing MOT between 2011 and 2021 with a kidney and additional solid organ has grown 23.4% [3]. Clinical management of MOT recipients is significantly more complex than single organ transplant, requiring more resources for monitoring and coordination between multiple clinical teams. Thus, there is a growing need to understand the applicability of emerging non-invasive biomarkers in this expanding high-risk population.

The physiological rationale for MOT is well-established across different clinical scenarios. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant (SPKT) improves outcomes in patients with diabetes and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [4]. Heart-kidney transplantation (HKT) benefits patients with coexisting cardiac and renal failure, a common clinical scenario resulting from the inter-independence of both organs [5], reducing the risk of calcineurin inhibitor (CNI)-induced nephrotoxicity during heart transplantation which has contributed to a six-fold rise in US transplants since 2010 [6]. Simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation (SLKT) treats end-stage liver disease with concomitant kidney impairment or ESRD [7, 8], a common complication in this population [9]. Also, patients who may not qualify for a kidney transplant alone due to significant cardiac or hepatic dysfunction may qualify through the addition of the heart or liver allograft.

Traditional biomarkers for monitoring acute rejection (AR) in MOT are limited in their prognostic utility. For example, serum creatinine (sCr), proteinuria, amylase, lipase, and liver enzymes (like alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)) are non-specific and can be confounded by unrelated factors [10–12]. Heart transplant biomarkers like B-type natriuretic (BNP) and N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) are weakly-associated with heart transplant rejection [13]. Although biopsy remains the gold standard, its invasive nature and susceptibility to sampling error highlight the need for non-invasive biomarkers with improved sensitivity and specificity for organ injury in patients with MOT.

Donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) is a validated biomarker for detecting AR in kidney [14, 15], lung [16], and heart single-organ transplant recipients [17]. Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated the high negative predictive value and strong correlation of dd-cfDNA with molecular and histologic rejection phenotypes across single-organ transplant types [18–22]. While dd-cfDNA was historically reported as a fraction of total circulating cf-DNA, studies have demonstrated that quantification of the plasma concentration of dd-cfDNA improves discrimination of rejection and reduces confounding from fluctuations in total cfDNA [23, 24]. Moreover, the combination of dd-cfDNA fraction and a donor quantity score (DQS), which estimates the quantity of dd-cfDNA in copies per mL of patient’s plasma, has also been shown to improve accuracy in the detection of AR with rejection thresholds of ≥1.0% and/or ≥78 cp/mL in kidney [25, 26], and ≥0.26% and/or ≥18 cp/mL in heart transplants [27]. While dd-cfDNA has been studied and characterized in SPKT recipients in a single-center study [28], its behavior in other MOT combinations remains largely unexplored, highlighting the need for additional research.

Here we introduce the “Use of dd-cfDNA in Multi-Organ Transplant Recipients” (MOTR) study; a multicenter, prospective, cross-sectional study designed to evaluate the dd-cfDNA baseline levels in real-world cohort of MOT recipients who were either clinically stable or who underwent a scheduled biopsy of at least one transplanted organ. This study analyzed dd-cfDNA levels, as a fraction (%), and donor quantity score (DQS; copies/mL) in pancreas-kidney (PK), heart-kidney (HK), and liver-kidney (LK) transplant recipients, and compared them to matched, real-world single-organ KT and HT recipients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The MOTR study was an international, prospective, cross-sectional, multicenter study that evaluated dd-cfDNA baseline levels in patients with MOT. The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by local or central institutional review boards (IRBs, Supplementary Table S1). All PK, HK and LK transplant recipients who met the eligibility criteria were consented according to the IRB-approved protocol. The study has been performed in full adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients were considered eligible for enrollment into the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) age ≥18 years at the time of signing informed consent, (2) history of pancreas-kidney, kidney-heart, or liver-kidney transplant, (3) either considered clinically stable (defined as no history of rejection or no clinical indication of rejection within 3 months prior to enrollment in the study), or scheduled to undergo a biopsy of at least one of the transplanted organs, (4) able to read, understand, and provide written informed consent, and (5) willing and able to comply with the study-related procedures. Patients were excluded from this study if, at the time of enrollment they (1) were pregnant, (2) were on dialysis, (3) had received an allograft from an identical twin, and/or (4) had more than 2 unique organ transplant types (i.e.: pancreas, liver, heart).

Clinical and biological data related to recipient characteristics, donor characteristics, transplant procedure, and contemporaneous laboratory tests including SCr, lipase, amylase, ALP, AST, ALT, DSA, and viral loads, were collected for patients in both the stable arm and the biopsy-matched arm (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Recipient characteristics | All patients (N = 347) | Pancreas-kidney Cohort (N = 183) | Heart-kidney cohort (N = 57) | Liver-kidney (N = 107) | P valuea | Pairwise p-valuesb PKT-HKT PKT-LKT HKT-LKT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.1 (48.7–65.9) | 51.1 (45.4–57.3) | 62.1 (54.6–68.9) | 64.8 (59.3–71.1) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 <0.0001 0.2901 |

| Sex ratio Male Female | 224 (64.6%) 123 (35.4%) | 115 (62.8%) 68 (37.2%) | 45 (78.9%) 12 (21.1%) | 64 (59.8%) 43 (40.2%) | 0.0398 | 0.1094 1.0000 0.0647 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.2 (24.9–32.7) | 27.2 (24.1–31.8) | 28.9 (26.0–32.9) | 29.0 (26.0–33.4) | 0.0404 | 0.1958 0.0828 1.0000 |

| Time from most recent transplant to dd-cfDNA testing (months) | 23.5 (8.4–52.7) | 33.8 (9.2–73.9) | 13.1 (6.4–33.2) | 19.0 (8.2–41.8) | 0.0001 | 0.0003 0.0220 0.2001 |

| Race White African American Other Asian Unknown | 179 (51.6%) 96 (27.7%) 6 (1.7%) 11 (3.2%) 55 (15.9%) | 82 (44.8%) 44 (24.0%) 4 (2.2%) 3 (1.6%) 50 (27.3%) | 18 (31.6%) 32 (56.1%) 0 (0.0%) 5 (8.8%) 2 (3.5%) | 79 (73.8%) 20 (18.7%) 2 (1.9%) 3 (2.8%) 3 (2.8%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 <0.0001 <0.0001 |

| Ethnicity Not hispanic or latino Hispanic or latino Unknown | 263 (75.8%) 28 (8.1%) 56 (16.1%) | 116 (63.4%) 16 (8.7%) 51 (27.9%) | 53 (93.0%) 3 (5.3%) 1 (1.8%) | 94 (87.9%) 9 (8.4%) 4 (3.7%) | <0.0001 | 0.0002 <0.0001 1.000 |

| Contemporaneous DSA status to dd-cfDNA testing Yes No | 23 324 | 12 171 | 7 50 | 4 103 | 0.1115 | 0.7925 1.0000 0.2379 |

| Transplant sequence Non-simultaneous Simultaneous Repeat | 36 (10.4%) 303 (87.3%) 8 (2.3%) | 7 (3.8%) 169 (92.3%) 7 (3.8%) | 3 (5.3%) 52 (91.2%) 2 (3.5%) | 26 (24.3%) 80 (74.8%) 1 (0.9%) | <0.0001 | 0.8934 <0.0001 0.00181 |

| Biopsies For-cause For-protocol Not reported | 49 (14.1%) 48 (13.8%) 250 (72.0%) | 34 (18.6%) 6 (3.3%) 143 (78.1%) | 7 (12.3%) 27 (47.4%) 23 (40.4%) | 8 (7.5%) 15 (14.0%) 84 (78.5%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 0.0008 <0.0001 |

| Mortality status Alive Died | 345 (99.4%) 2 (0.6%) | 182 (99.5%) 1 (0.5%) | 57 (100.0%) 0 (0.0%) | 106 (99.1%) 1 (0.9%) | 0.7509 | 1.0000 1.0000 1.0000 |

| Kidney donor characteristics | ||||||

| Donor age (years) | 32.0 (22.0–41.0) | 27.0 (20.0–35.0) | 33.0 (27.0–45.0) | 40.0 (30.2–49.0) | <0.0001 | 0.0009 <0.0001 0.0768 |

| Donor relationship to recipient Not related Biologically related | 342 (98.6%) 5 (1.4%) | 178 (97.3%) 5 (2.7%) | 57 (100.0%) 0 (0.0%) | 107 (100.0%) 0 (0.0%) | 0.1030 | 1.0000 0.6259 1.0000 |

| Donor type Living DCD DBD Not reported | 11 (3.2%) 43 (12.4%) 270 (77.8%) 23 (6.6%) | 7 (3.8%) 22 (12.0%) 144 (78.7%) 10 (5.5%) | 3 (5.3%) 2 (3.5%) 47 (82.5%) 5 (8.7%) | 1 (0.9%) 19 (17.8%) 79 (73.8%) 8 (7.5%) | 0.1190 | 0.7209 0.7031 0.0805 |

| KDPI | 23.0 (6.0–41.0) | 11.0 (0.0–26.0) | 28.0 (15.2–46.5) | 39.0 (24.0–64.0) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 <0.0001 0.0424 |

| Pancreas/Heart/Liver donor characteristics (non-simultaneous) | ||||||

| Donor age (years) | 28.0 (20.5–39.5) | 20.0 (17.5–24.5) | 29.0 (24.8–32.5) | 33.0 (25.5–45.0) | 0.0090 | 0.6017 0.0088 1.0000 |

| Donor type DCD DBD Not reported | 3 (6.5%) 36 (78.3%) 7 (15.2%) | 1 (7.1%) 7 (50.0%) 6 (42.9%) | 0 (0.0%) 5 (100.0%) 0 (0.0%) | 2 (7.4%) 24 (88.9%) 1 (3.7%) | 0.0132 | |

Demographics and clinical characteristics of MOTR study patients.

Categorical variables are shown as median (IQR). BMI: body mass index, dd-cfDNA: Donor-derived cell-free DNA, DSA: donor specific antibodies, CPRA: calculated panel reactive antibody, DCD: donation after cardiac death, DBD: donation after brain death, KDPI: kidney donor profile index, CMV: cytomegalovirus, EBV: Epstein-Barr virus, HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus.

Kruskal-Wallis test comparing PKT, HKT, and LKT, cohorts.

Post-hoc Mann-Whitney U or Chi-Square test comparing PKT-HKT, PKT-LKT, and HKT-LKT, with Bonferroni correction for significant Kruskal-Wallis values.

dd-cfDNA Testing

dd-cfDNA samples were analyzed using the methodology previously described (the Prospera™ test; Natera, Inc., Austin, TX) [29]. Blood samples for dd-cfDNA testing were collected in two 10 mL Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT tubes and shipped at room temperature to Natera’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified and College of American Pathologists-accredited laboratory. Samples were processed within 8 days of collection, or according to previously validated standard operating protocol [30]. The algorithm was designed to provide a single composite value by combining non-recipient cfDNA for both dd-cfDNA % and DQS, which is an estimate of the concentration of dd-cfDNA in plasma reported as genomic copies per mL (cp/mL). Blood draws for dd-cfDNA testing were performed within 0–7 days before biopsy in the biopsy-matched arm, or according to clinical standard in the stable arm. Results of the investigational test (dd-cfDNA) were not shared with the patients or the attending physicians, and thus not used in patient management.

Biopsy Classification

Allograft biopsies of kidney, pancreas, heart, and liver transplants were graded as previously reported [31–34]. Biopsy reports were centrally reviewed by pathologists for data accuracy.

Statistical Analysis

dd-cfDNA levels in PKT, HKT, LKT recipients were compared to real-world cohorts of KT and HT recipients matched for time post-transplant.

Statistical analyses were performed in Python (3.8.10). Normally distributed variables were reported as mean and standard deviation; non-normally distributed variables were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were represented as counts and percentages and evaluated using Chi-square test as appropriate. Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed for groupwise comparisons. For significant p-values, post-hoc tests of chi-square or Mann Whitney U tests were performed, as appropriate, with Bonferroni corrections for multiple testing.

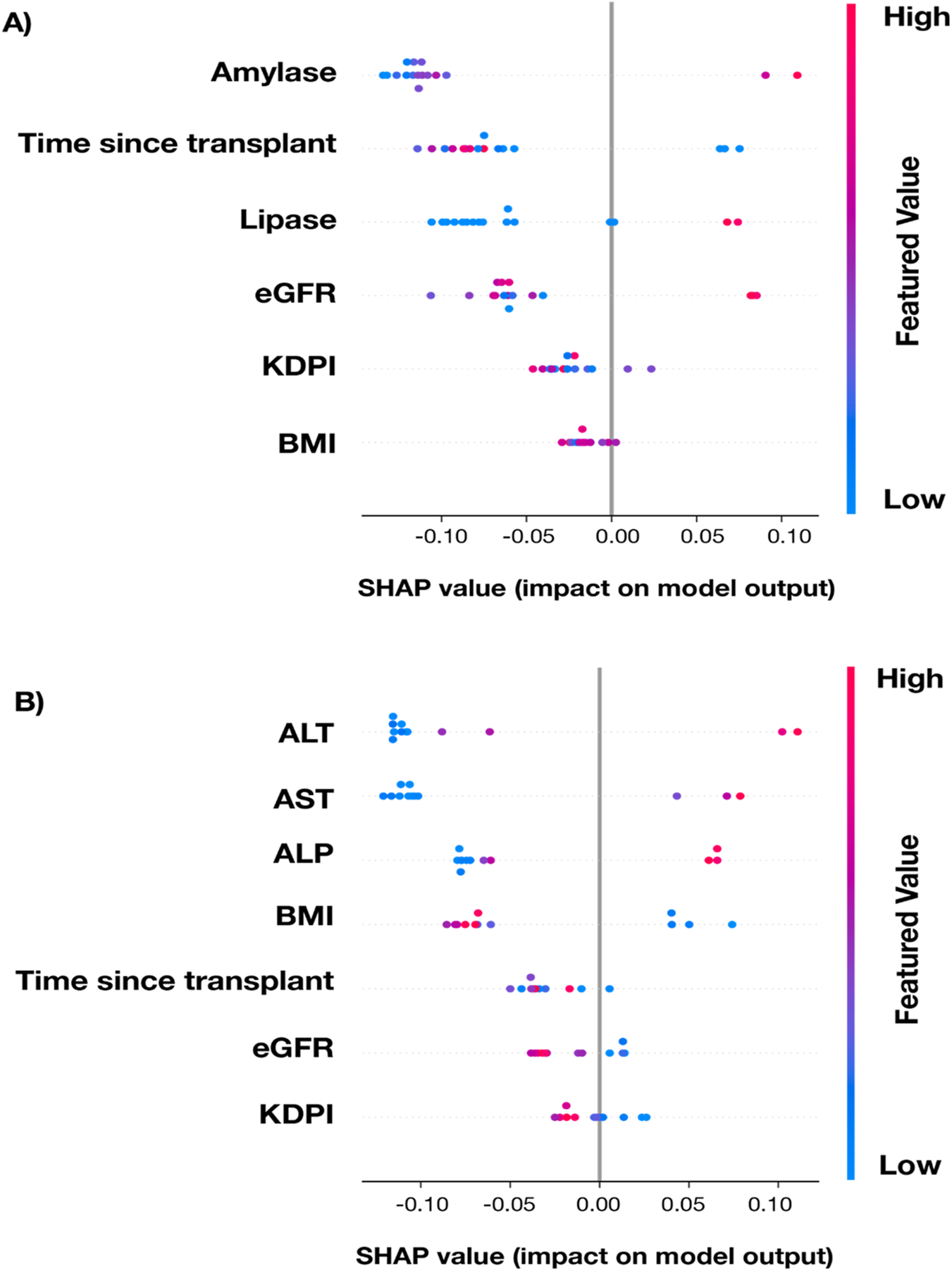

Random forest classifiers were applied to identify the relationship between known clinical variables and positivity of dd-cfDNA (i.e., high risk by dd-cfDNA) testing. dd-cfDNA positivity was defined using the clinical thresholds established for kidney-alone transplant rejection (dd-cfDNA%≥1.0% OR DQS≥78.0 cp/mL) for the PKT and HKT cohorts, and an investigational, unvalidated threshold for liver-alone transplant rejection (dd-cfDNA%≥10.0%) based on prior studies [35–37] for the LKT cohort. Modeling was not feasible in the HKT cohort due to the limited number of dd-cfDNA-positive cases. Modeling included PKT cases with complete known matched eGFR (estimated glomerular filtration rate), amylase and lipase values, and LKT cases with complete known matched eGFR, ALP, AST, and ALT values, and was trained on these values along with time from transplant, Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI), and body mass index (BMI) and optimized for F1 score. The Shapley values of these features were assessed on a holdout random set of 20% of the complete cases.

Spearman correlation analyses were performed between dd-cfDNA (%, cp/mL) and the clinical biomarkers relevant to each transplanted organ, as described above. For each variable pair, correlation was calculated using cases with complete data.

SRTR Database

This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The SRTR data system includes data on all donor, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the US, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. Contemporaneous data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) was assessed for comparison.

The data reported here have been supplied by the Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute (HHRI) as the contractor for SRTR. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the U.S. Government.

Contemporaneous data from SRTR were queried to compare the MOTR study cohorts (PKT, HKT, and LKT) to the corresponding national cohorts for each MOT type, to assess representativeness and generalizability. Variables included MOT recipient age, sex, BMI, race/Ethnicity, and repeat transplant status as indicated in Supplementary Table S2.

Results

Study Cohort

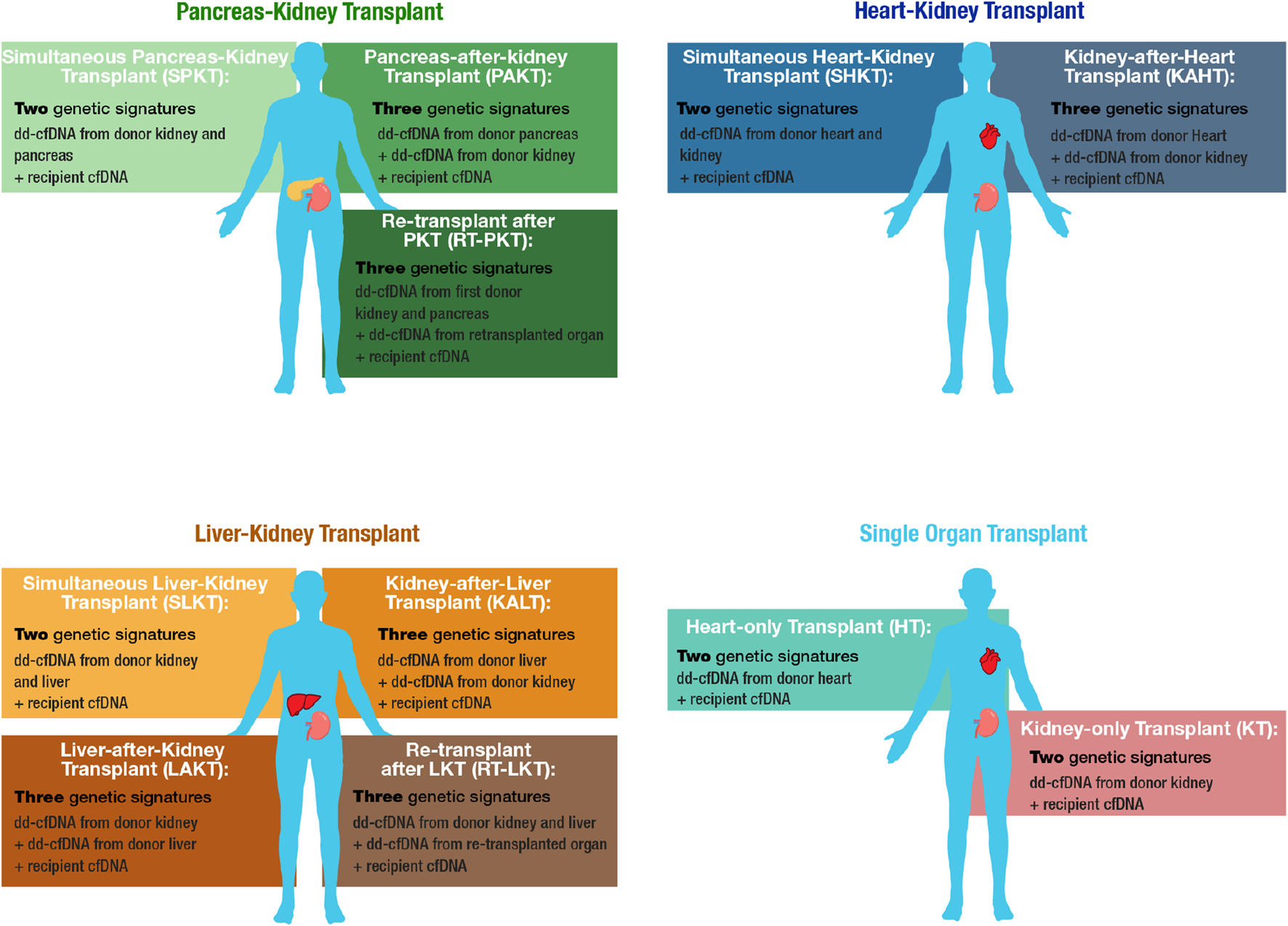

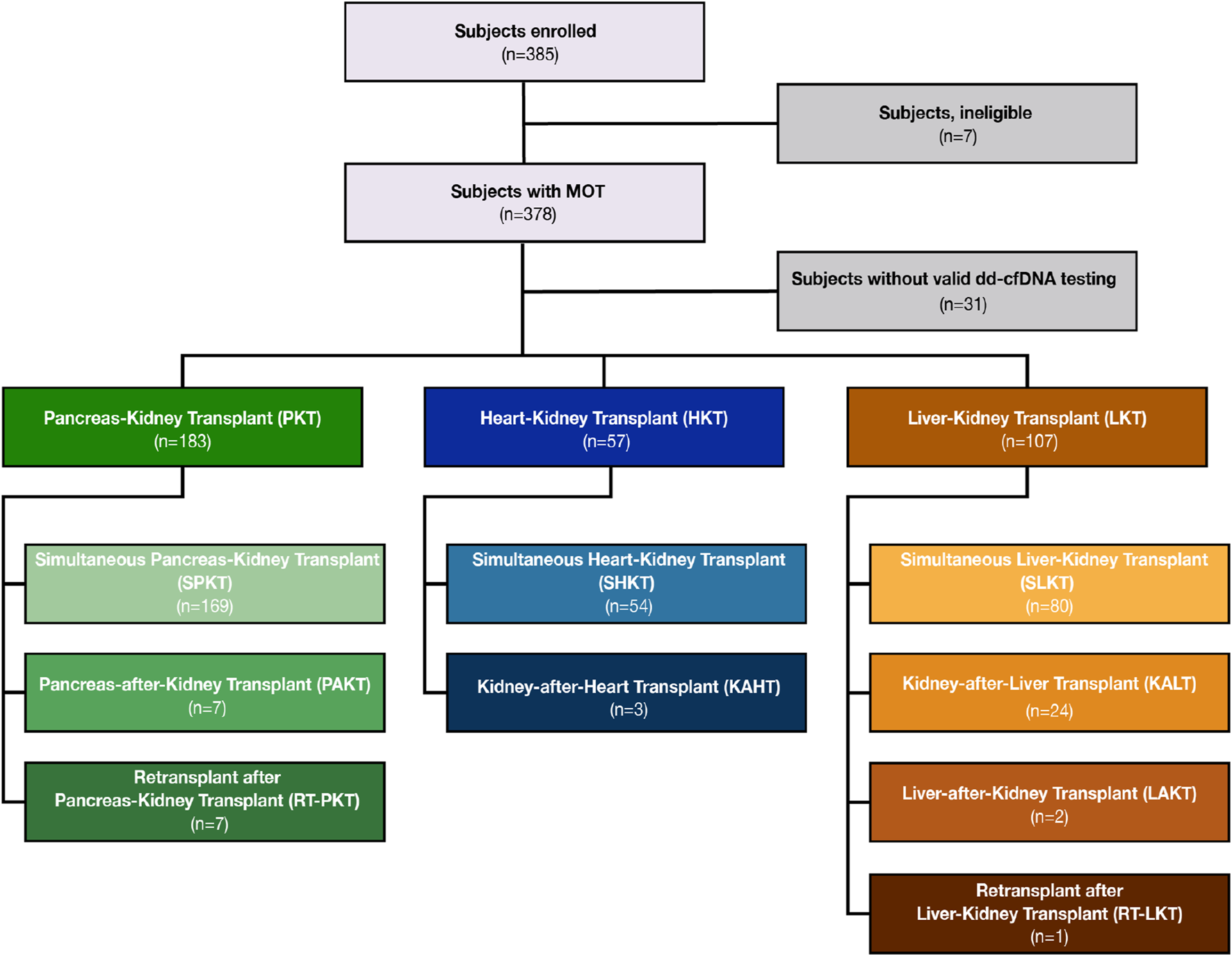

Between October 2020 and June 2022, 385 subjects from 18 sites were enrolled in the MOTR Study (Supplementary Table S1). Of these, 38 subjects were excluded due to ineligibility or lack of valid dd-cfDNA testing (e.g., insufficient plasma volume). Of the remaining 347 transplant recipients, 183 had PKT, including 169 with a simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant (SPKT; 92.4%), 7 with a pancreas-after-kidney transplant (PAKT; 3.8%). 7 patients (3.8%) underwent repeat transplant following a kidney-pancreas transplant: Four received kidney re-transplant after SPK, and three received a pancreas retransplant (one after PAK, two after SPK). 57 subjects had HKT, including 54 with a simultaneous heart-kidney transplant (SHKT; 94.7%) and 3 with a kidney-after-heart transplant (KAHT; 5.3%). 107 subjects had LKT including 80 with a simultaneous kidney-liver transplant (SLKT; 74.8%), 24 with a kidney-after-liver transplant (KALT; 22.4%), two with a liver-after-kidney transplant (LAKT; 1.9%), and one (0.9%) with a liver re-transplant following a kidney-after-liver transplant (Figures 1, 2).

FIGURE 1

Overview of MOT cohorts and corresponding cfDNA constituents. MOT cohorts include Pancreas-Kidney transplant (PKT), Heart-Kidney transplant (HKT), and Liver-Kidney transplant (LKT). Matched-single-organ transplant cohorts, kidney-only transplant (KT) and heart-only transplant (HT), serve as comparators.

FIGURE 2

CONSORT diagram of study enrollment and breakdown of organ groups by transplant sequence.

The MOTR cohort was 64.6% male (n = 224), had a median age of 57.1 y (IQR: 48.7–65.9), and a median BMI of 28.2 kg/m2 (IQR: 24.9–32.7). Patients were 51.6% White, 27.7% African American, and 8.1% Hispanic and/or Latino. In the PKT, HKT, and LKT cohorts, 3.8% (7/183), 5.3% (3/57), and 0.9% (1/107) of the transplanted kidneys were donated by living donors, respectively. The median KDPI across all deceased donor’s kidney transplants was 23.0 (IQR: 6.0–41.0). The majority (72%) of MOTR participants were considered clinically stable at enrollment, and the remaining 28% underwent biopsy; (for-cause: n = 49, 50.5%; for-protocol: n = 48, 49.5%) (Table 1). For-cause and for-protocol biopsies were observed in 18.6% and 3.3% of PKT, 12.3% and 47.4% of HKT, and 7.5% and 14.0% of LKT recipients, respectively; 70% of all biopsies were performed on the transplanted kidney.

The covariates of the PKT, HKT, and LKT subcohorts, such as MOT recipient demographics including age, sex, and ethnicity, were also compared to a contemporaneous national cohort’s covariates as represented in data requested from the SRTR (https://www.srtr.org/) (Supplementary Table S2).

dd-cfDNA Fraction and DQS Estimates

In this analysis, a single dd-cfDNA test from each patient was used, along with a matched biopsy, when available. The median time from most recent transplant to dd-cfDNA testing was 23.5 months (IQR: 8.4–52.7) and was significantly longer in the PKT cohort (33.8 months) compared to the HKT (13.1 months) and LKT (19.0 months) cohorts (p < 0.05).

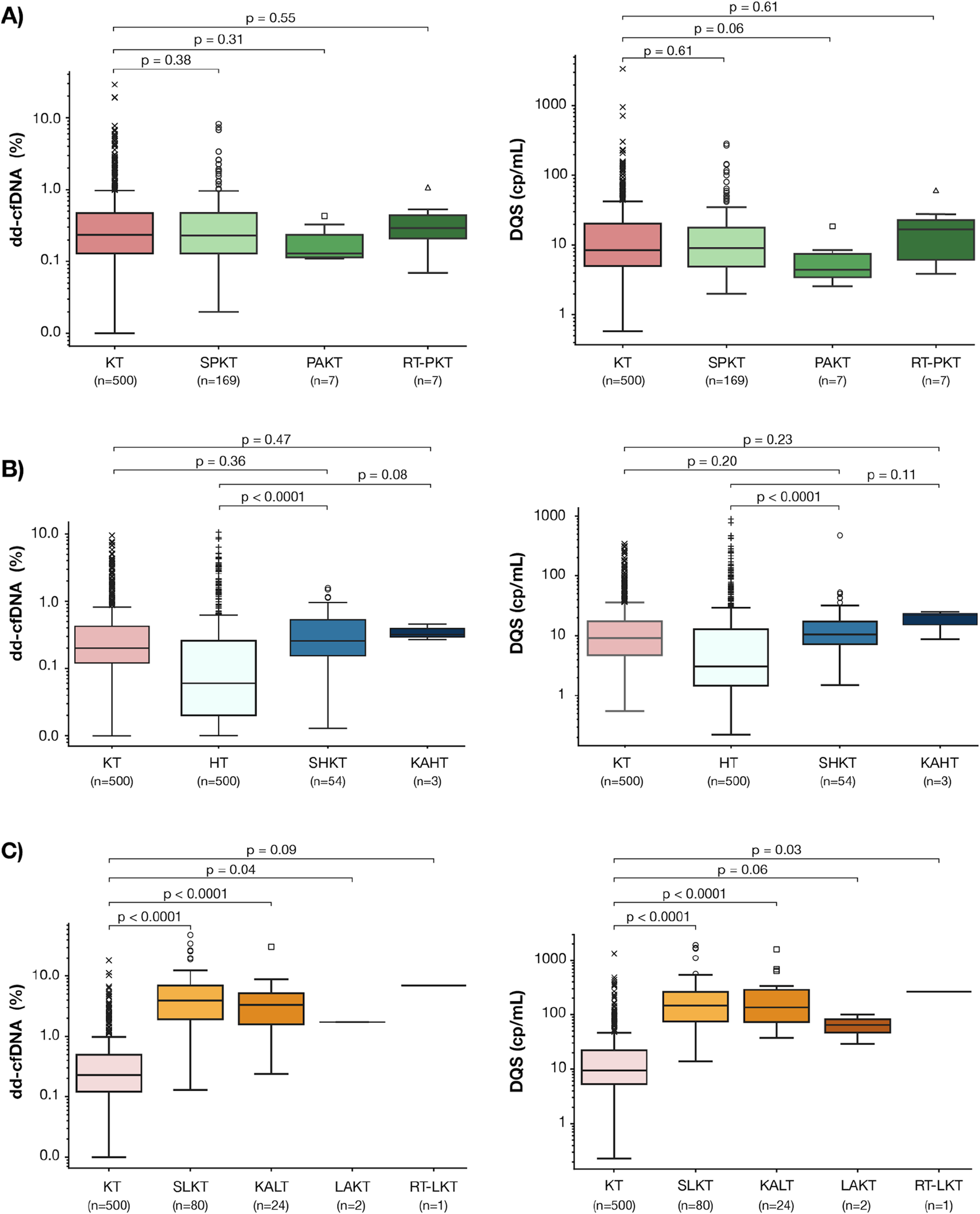

Among the PKT recipients, there were no significant differences in the median (IQR) dd-cfDNA % or DQS between the SPKT (dd-cfDNA%: 0.23% (0.13–0.47); DQS: 9 (4–17) cp/mL), PAKT (dd-cfDNA%: 0.13% (0.11–0.23); DQS: 4 (3–7) cp/mL) or those who underwent kidney or pancreas retransplant after PKT (dd-cfDNA%: 0.29% (0.21–0.44); DQS: 16 (6–22) cp/mL) cohorts and the KT cohort (dd-cfDNA%: 0.23% (0.12–0.48); DQS: 9 (5–20) cp/mL) (p = 0.38, 0.31, and 0.55, respectively) (Figure 3A). The distribution of total cfDNA paralleled that of both dd-cfDNA (%) and DQS (cp/mL) among these groups (Supplementary Figure S1A).

FIGURE 3

Baseline dd-cfDNA fraction (%) and DQS (cp/mL) levels in the PKT (A), HKT (B), and LKT (C) sub-cohorts. Box-and-whisker plots display the median and interquartile range (IQR); whiskers extend to 1.5x IQR representing the expected data range; outliers beyond this range are shown as individual points. P values denote pairwise comparisons in dd-cfDNA levels between: (A) SPKT, PAKT, and PK-RT and KT cohorts, (B) SHKT, KAHT and KT, HT cohorts, (C) SLKT, KALT, LAKT, KL-RT and KT cohorts. PKT: Kidney-Pancreas transplant, SPKT: Simultaneous Kidney-Pancreas transplant, PAKT: Pancreas-after-Kidney transplant, PK-RT: Pancreas-Kidney Repeat transplant, KT: Kidney transplant, HT: Heart transplant, HKT: Kidney-Heart transplant, KAHT: Kidney-after-Heart transplant, SLKT: Simultaneous kidney-liver transplant, KALT: Kidney-after-liver transplant, LAKT: Liver-after-kidney transplant, KL-RT: Kidney-liver Repeat transplant.

Similarly, among the HKT recipients, there were no significant differences in the median (IQR) dd-cfDNA % or DQS (cp/mL) between the SHKT (dd-cfDNA%: 0.21% (0.12–0.42); DQS: 10 (7–18) cp/mL) or the KAHT cohorts (dd-cfDNA%: 0.32% (0.30–0.39; DQS: 22 (15–23) cp/mL) and the KT cohort (dd-cfDNA%: 0.24% (0.12–0.51); DQS: 10 (5–22) cp/mL (p = 0.36, 0.47, respectively) (Figure 3B). Both the median dd-cfDNA % and DQS (cp/mL) were significantly higher among the SHKT cohort when compared to the HT cohort (dd-cfDNA%: 0.21% (0.12–0.42); DQS: 10 (7–18) cp/mL) vs. (dd-cfDNA%: 0.06 (0.02–0.21), DQS: 2 (1–11) cp/mL, p < 0.001) (Figure 3B). There were no differences in total cfDNA when comparing SHKT and KAHT to KT and SHKT and KAHT to HT cohorts (Supplementary Figure S1B).

Among the LKT recipients, both the median (IQR) dd-cfDNA % and DQS for the SLKT (dd-cfDNA%: 3.92% (1.92–6.99); DQS: 147 (75–258) cp/mL) and KALT cohorts (dd-cfDNA%: 3.35% (1.59–5.14); DQS: 35 (73–284) cp/mL) were significantly higher than the KT (dd-cfDNA%: 0.23% (0.12–0.49); DQS: 9 (5–22) cp/mL; p < 0.001 for both) (Figure 3C). Lower total cfDNA levels in the SLKT compared to the KALT cohort may contribute to differences between dd-cfDNA% and DQS (cp/mL) observed between them (Supplementary Figure S1C).

Patients With Biopsy-Proven Acute Rejection (BPAR)

While this study did not contain sufficient patients with BPAR to assess appropriate dd-cfDNA cutoffs for rejection risk in MOT, we felt it was still illustrative to interpret the data in the context of the validated kidney-only threshold, as we would expect the dd-cfDNA values for kidney-only transplant patients to approximate a lower-bound for the appropriate MOT rejection risk threshold. A total of three patients in the SPKT cohort had kidney BPAR, two of which had dd-cfDNA above the 1.0% threshold used to define increased rejection risk in KT recipients (Supplementary Figure S2A): one recipient with T-cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) had dd-cfDNA levels of 3.11% and 63 cp/mL, while two patients with chronic active antibody-mediated rejection (AMBR) had dd-cfDNA% of 0.51% and 1.59% and DQS of 21 and 55 cp/mL. Three patients among the LKT cohort had BPAR in the kidneys (Supplementary Figure S2B), including TCMR 1A with dd-cfDNA of 1.32%, 86 cp/mL, chronic active ABMR (2.31%, 114 cp/mL), and ABMR (6.98%, 698 cp/mL). No patients in the HKT cohort showed acute rejection on biopsy (Supplementary Figure S2B). Of the remaining 91 biopsies, 68 showed no rejection, 18 showed other findings not representing rejection, and 5 consisted of limited sample tissue and were thus unable to be diagnosed.

Patients With dd-cfDNA Values Above Thresholds for Kidney-Only Transplant Rejection

Of the 240 non-rejecting PKT and HKT recipients, 21 (19 PKT and 2 HKT) exceeded KT dd-cfDNA thresholds (≥1.0% and/or ≥78 copies/mL). All but one of these transplants were simultaneous; the remaining one was a kidney re-transplant after SPK. Seven patients (33.%) underwent biopsies (6 kidney, 1 heart), all without significant findings. The remaining 14 patients (13 PKT, 1 HKT) were considered clinically stable and did not undergo biopsy; one of these had substantially elevated amylase levels, while the other 13 were clinically stable by all parameters apart from dd-cfDNA. Of the 219 patients with dd-cfDNA below KT threshold, only one experienced BPAR (chronic-active ABMR).

Of the 107 subjects in the LKT cohort, 12 (11.2%; 11 SLKT, 1 KALT) had dd-cfDNA above 10%, which prior studies have posited as an appropriate threshold for rejection in liver-only transplants [35–37]. Two of these subjects received surveillance biopsies of the kidney, both demonstrating no rejection; no patients received biopsies of the liver.

Variables Associated With Elevated dd-cfDNA Levels in MOT Recipients

We sought to identify the clinical variables in MOT recipients that were associated with elevated dd-cfDNA levels using a random forest classifier with the PKT (Figure 4A) and LKT (Figure 4B) cohorts. The traditional markers for respective organ function were chosen as variables. In the PKT cohort, the most influential variables included amylase, time since transplant, and lipase. Shorter time post-transplant, higher amylase values, and higher lipase values were associated with higher likelihood of elevated dd-cfDNA (Figure 4A). Looking at the continuous relationship between dd-cfDNA and the laboratory markers in the PKT cohort, significant positive correlations were observed in the PKT cohort between dd-cfDNA% and amylase and lipase (p < 0.001, 0.006, respectively), as well as between DQS and amylase and lipase (p = 0.006, 0.027, respectively). eGFR did not show a significant association with dd-cfDNA in either the random forest model or using Spearman correlations (Supplementary Figure S3).

FIGURE 4

SHAP (SHapely Additive exPlanations) summary plot for a randomly-selected holdout testing subset of cases with complete data from the PKT (A) and LKT (B) transplant cohorts displaying the contribution of key variables to the random forest model’s prediction of increased-risk dd-cfDNA results. Each dot represents an individual patient. SHAP values on the x-axis indicate the variable’s impact on the model output (positive values increase likelihood of positive result, negative values decrease it). Features are ranked by overall importance from top to bottom. Color represents the variable value, with blue indicating low values and red indicating high values.

In the LKT cohort, the most influential variables in the random forest classifier were ALT, AST, and ALP. Higher liver enzyme profiles were associated with higher likelihood of elevated dd-cfDNA (Figure 4B). Across all dd-cfDNA levels in this cohort, significant positive correlations were observed between dd-cfDNA% and ALT and AST (p < 0.001 for both), and between DQS and ALT and AST (p < 0.001 for both). No significant correlations were found between dd-cfDNA levels and eGFR (Supplementary Figure S4).

As the model indicated a significant association between time post-transplant and the likelihood of elevated dd-cfDNA levels, we further assessed the relationship between dd-cfDNA and time post-transplant in the different MOT cohorts (Supplementary Figure S5). In the PKT and HKT cohorts, dd-cfDNA% and DQS (cp/mL) both decreased over time. Total cfDNA remained steady in the PKT cohort while the HKT cohort showed a dramatic decrease in the first 40 months post-transplant before stabilizing. Despite these fluctuations, dd-cfDNA levels in both cohorts remained below the validated thresholds for KT rejection. In the LKT cohort, dd-cfDNA% and DQS increased slightly over time, whereas the total cfDNA decreased slightly, before stabilizing.

Discussion

This study represents the largest comprehensive characterization of dd-cfDNA (fraction and quantity) baseline levels in MOT recipients, addressing a gap in transplant biomarker research in this growing high-risk population. With characteristics comparable to the national SRTR registry, this cohort reflects real-world diversity and provides reference data for these populations. Key findings show that dd-cfDNA baselines vary by MOT combination and were generally aligned with known dd-cfDNA patterns from the major contributing organ: PKT and HKT had values comparable to KT recipients, while the higher dd-cfDNA levels in LKT recipients likely reflected the larger dd-cfDNA contribution from the liver transplants. Further, our data show associations between elevated dd-cfDNA and abnormal levels of traditional biomarkers used to test allograft functions indicating that dd-cfDNA levels reflect functional impairment of the respective transplanted organ (kidney, liver). Collectively, these data may help establish dd-cfDNA baseline levels for different MOT combinations, underscoring the potential for dd-cfDNA to serve as a non-invasive biomarker for rejection risk assessment in MOT recipients.

The release of dd-cfDNA from transplanted organs is influenced by several factors, including order of organ transplantation, organ size, organ vascularization, and cellular turnover rate [38]. The broad inclusion criteria include patients with both simultaneous and sequential transplants, allowing us to explore the impact of the order of organ transplant on dd-cfDNA levels. Our data suggests that the pancreas is the minor dd-cfDNA contributor in PKT recipients as the levels in SPKT were comparable to those of KT recipients. Similarly, the baseline dd-cfDNA levels in the HKT recipient’s cohort, including SHKT and KAHT, were comparable to those of KT recipients and significantly higher in SHKT than those of HT recipients, suggesting heart is the minor dd-cfDNA contributor relative to kidney. In contrast, dd-cfDNA levels were higher among the LKT cohort compared to KT recipients which is consistent with previous reports that LT recipients exhibit significantly higher dd-cfDNA levels than other solid organ transplants [35–37]. Given these data, it is not surprising that in this cohort, 2/3 PKT patients with kidney BPAR had dd-cfDNA above the 1.0% threshold established for KT rejection, as were 3/3 of the LKT patients with BPAR in the kidney. Of note, none of the three LKT patients with BPAR in the kidney had dd-cfDNA% above the exploratory 10% threshold proposed for liver transplant (LT) rejection; likely due to the lack of evidence of rejection in the liver of these patients. Taken together, these data suggest that the dd-cfDNA levels from the organ with the higher baseline may obscure rejections in the organ with the lower dd-cfDNA baseline, as seen in LKT and HKT (Supplementary Figure S2C). These findings underscore the importance of considering organ-specific dd-cfDNA levels when interpreting combined dd-cfDNA results in MOT populations and how it can be extrapolated from those established in single organ transplant recipients.

The clinical value of dd-cfDNA in MOT is further supported by its associations with abnormal levels in traditional biomarkers. In the PKT cohort, dd-cfDNA positivity was associated with increased serum amylase and lipase levels, suggesting that pancreas-derived injury signals correlate with higher dd-cfDNA release associated with rejection. Similarly, in the LKT cohort, strong associations between dd-cfDNA positivity and elevated liver enzymes (ALT, AST) are consistent with prior data suggesting that elevated dd-cfDNA levels in LT patients are associated with impaired liver function. These findings suggest that elevations in dd-cfDNA may serve as a sensitive indicator of allograft dysfunction across different transplanted organ types in MOT recipients.

In our study, the incidence of AR in our cohort (6.2%) was lower than that reported in similar MOT studies (24%) [39, 40] and (43%) [28]. This may reflect the large proportion of clinically stable patients enrolled in the study, which could be due to the relatively long post-transplant timeframe observed in this cohort. An added effect could be the immunoprotective role hypothesized in MOT recipients, which could explain the seemingly counterintuitive finding that rejection rates are lower in MOT than in single organ transplant. Previous studies have shown that patients with dual organ transplants involving the heart and/or liver, tend to exhibit greater graft stability compared to single transplants alone [41, 42]. While it was previously thought that only MOT patients with a liver allograft experienced this immunoprotective effect, data has now shown that other simultaneously-transplanted organs also have this immunologic benefit [8, 43, 44]. This effect was not observed in sequential transplants, indicating that shared antigenicity in simultaneous MOT may be required for immunoprotection to manifest [44]. In this study, the majority of participants were simultaneous MOT, which could have contributed to the lower incidence of AR via this ‘immunoprotective’ MOT mechanism.

A key challenge in MOT is identifying the graft undergoing rejection while managing immunosuppression to avoid toxicity. This becomes more complex when the transplanted organs are from different donors. The ability to discern the rejecting graft in these cases could be augmented by distinguishing between donor-specific cfDNA signatures, an approach proven feasible in a recent study of pregnant kidney recipients where fetal- and graft-derived cfDNA were successfully differentiated [45]. Analogous advances in noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT), such as SNP-based assays that enable precise attribution of cfDNA to individual fetuses in twin pregnancies, demonstrate that identifying the tissue origin of circulating cfDNA is feasible [46]. While this approach would not allow for differentiation of organ-specific dd-cfDNA in simultaneous MOT where the two transplanted organs are from the same donor, other studies have revealed that the cfDNA methylation patterns can be used to identify the tissue-of-origin, independent of donor number or type [47].

This study has several limitations. First, biopsy data were not available for 72% of patients, with the designation of “non-rejecting” made based on clinical characteristics, and of those patients with a biopsy, very few patients had a biopsy from both organs. Second, the overall number of BPAR cases was insufficient to allow determination of a dd-cfDNA threshold for the clinical detection rejection in MOT recipients. Third, the study did not differentiate between dd-cfDNA contributions from multiple donors in MOT recipients, limiting the ability to precisely attribute dd-cfDNA elevations to a specific organ. Fourth, this analysis was cross-sectional in nature, limiting the assessment of the dynamic changes of dd-cfDNA over time.

In conclusion, this study is the largest of its kind, in which dd-cfDNA% and DQS baselines were characterized in pancreas-kidney, heart-kidney, and liver-kidney transplant recipients. This study provides foundational insights into how dd-cfDNA levels differ among and between different combinations of MOT, how dd-cfDNA levels relate to more traditional rejection biomarkers, and how these levels may be interpreted relative to each other. Future longitudinal studies focusing on MOT cohorts are needed to develop clinically valid assays to detect and define thresholds of organ-specific dd-cfDNA and improve rejections detection in these complex transplant scenarios.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

This study involved human subjects. All patients who met the eligibility criteria were consented according to local or central institutional review-board approved protocol, in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. A list of all IRB is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Author contributions

GaG contributed to conceptualization, investigation, methodology, resources, and writing (original draft, review and editing); DW, AS, TG, TD, NC, JO, RD, VR, and SA contributed to investigation, resources, and writing (original draft, review and editing); DGB contributed to data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, software, visualization, and writing (original draft, review and editing); DaB. contributed to formal analysis, investigation, software, visualization, and writing (review and editing); NK contributed to conceptualization, data curation, methodology, project administration, supervision, and writing (original draft, review and editing); GeG contributed to data curation, formal analysis, investigation, and writing (review and editing); EA contributed to methodology, validation, and writing (review and editing); JX and CS contributed to data curation, validation, and writing (review and editing); NA and MB contributed to visualization and writing (original draft, review and editing); ZD contributed to conceptualization, visualization, and writing (original draft, review and editing); AP contributed to conceptualization, project administration, supervision, and writing (review and editing); PG contributed to conceptualization, methodology, project administration, supervision, and writing (review and editing); SB contributed to conceptualization, project administration, supervision, and writing (original draft, review and editing); and HT contributed to conceptualization, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, and writing (original draft, review and editing). All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The authors declare that this study received funding from Natera, Inc. The funder had the following involvement with the study: study design, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of this article, and publication.

Conflict of interest

GaG reports institutional research support from Merck and Veloxis (through Virginia Commonwealth University); consulting or advisory roles with Appellis, CareDx, Eurofins-Viracor, Natera, Novartis, and Specialist Direct; and honoraria from CareDx. He serves as Chair of the Kidney Pancreas Community of Practice of the American Society of Transplantation. DW received grants and/or contracts and consulting fees from Natera. AS reports institutional research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). TG reports research support from a grant funded by the American Society of Transplantation. JO reports support from Veloxis, received royalties for content contributed to UpToDate, and reports grant support from Breakthrough T1D. RD serves on the Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) of an NIH-sponsored clinical trial. SA reports consulting or advisory roles with Natera and Transplant Genomics and has received honoraria from Verici and Natera. DGB, DaB, NK, GeG, EA, JX, CS, NA, MB, AP, PG, SB, and HT are employees of Natera, Inc., and receive salary and may own stock and/or stock options. ZD is a named inventor on several patents and is an employee of Natera, Inc., and receives salary and may own stock and/or stock options.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ti.2025.15823/full#supplementary-material

Glossary

- ABMR

antibody-mediated rejection

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- AMBR

antibody-mediated rejection

- AR

acute rejection

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI

body mass index

- BNP

B-type natriuretic peptide

- BPAR

biopsy-proven acute rejection

- cfDNA

cell-free DNA

- CNI

calcineurin inhibitor

- cp/mL

copies per milliliter

- dd-cfDNA

donor-derived cell-free DNA

- DQS

donor quantity score

- DSA

donor-specific antibodies

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HK

heart–kidney

- HKT

heart–kidney transplant

- HT

heart transplant

- IQR

interquartile range

- KAHT

kidney-after-heart transplant

- KALT

kidney-after-liver transplant

- KDPI

Kidney Donor Profile Index

- KT

kidney transplant

- LAKT

liver-after-kidney transplant

- LK

liver–kidney

- LKT

liver–kidney transplant

- LT

liver transplant

- MOT

multi-organ transplantation

- MOTR

Multi-Organ Transplant Recipients study

- NIPT

noninvasive prenatal testing

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- PAK

pancreas-after-kidney transplant

- PAKT

pancreas-after-kidney transplant

- PKT

pancreas–kidney transplant

- sCr

serum creatinine

- SHKT

simultaneous heart–kidney transplant

- SPKT

simultaneous pancreas–kidney transplant

- SLKT

simultaneous liver–kidney transplant

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

- TCMR

T-cell–mediated rejection

References

1.

LangFMTopkaraVK. Evolving Indications and Management Patterns in Heart - Kidney Transplantation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens (2025) 34(1):16–22. 10.1097/MNH.0000000000001042

2.

WestphalSGLangewischEDMilesCD. Current State of Multiorgan Transplantation and Implications for Future Practice and Policy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis (2021) 28(6):561–9. 10.1053/j.ackd.2021.09.012

3.

LentineKLSmithJMMillerJMBradbrookKLarkinLWeissSet alOPTN/SRTR 2021 Annual Data Report: Kidney. Am J Transpl (2023) 23(2 Suppl. 1):S21–S120. 10.1016/j.ajt.2023.02.004

4.

NagendraLFernandezCJPappachanJM. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney Transplantation for end-stage Renal Failure in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: Current Perspectives. World J Transpl (2023) 13(5):208–20. 10.5500/wjt.v13.i5.208

5.

BanerjeeDAliMAWangAYJhaV. Acute Kidney Injury in Acute Heart failure-when to Worry and when Not to Worry?Nephrol Dial Transpl (2024) 40(1):10–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfae146

6.

JainRKittlesonMM. Evolutions in Combined Heart-Kidney Transplant. Curr Heart Fail Rep (2024) 21(2):139–46. 10.1007/s11897-024-00646-0

7.

AliHBegum OzturkNHerdanNELuuHSimsekCKazanciogluRet alCurrent Status of Simultaneous liver-kidney Transplantation. Hepatol Forum (2024) 5(4):207–10. 10.14744/hf.2023.2023.0071

8.

ZhangIWLurjeILurjeGKnosallaCSchoenrathFTackeFet alCombined Organ Transplantation in Patients with Advanced Liver Disease. Semin Liver Dis (2024) 44(3):369–82. 10.1055/s-0044-1788674

9.

BeraCWongF. Management of Hepatorenal Syndrome in Liver Cirrhosis: A Recent Update. Therap Adv Gastroenterol (2022) 15:17562848221102679. 10.1177/17562848221102679

10.

JahnNVoelkerMTLaudiSStehrSSchneebergerSBrandacherGet alCorrelation of Different Serum Biomarkers with Prediction of Early Pancreatic Graft Dysfunction Following Simultaneous Pancreas and Kidney Transplantation. J Clin Med (2022) 11(9):2563. 10.3390/jcm11092563

11.

ZhouHHewittSMYuenPSStarRA. Acute Kidney Injury Biomarkers - Needs, Present Status, and Future Promise. Nephrol Self Assess Program (2006) 5(2):63–71.

12.

GermaniGRodriguez-CastroKRussoFPSenzoloMZanettoAFerrareseAet alMarkers of Acute Rejection and Graft Acceptance in Liver Transplantation. World J Gastroenterol (2015) 21(4):1061–8. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i4.1061

13.

ZhuVPerryLAPlummerMSegalRSmithJLiuZ. Diagnostic Accuracy of Brain Natriuretic Peptide and N-terminal-pro Brain Natriuretic Peptide to Detect Complications of Cardiac Transplantation in Adults: A Systematic Review and meta-analysis. Transpl Rev (Orlando) (2023) 37(3):100774. 10.1016/j.trre.2023.100774

14.

SigdelTKArchilaFAConstantinTPrinsSALibertoJDammIet alOptimizing Detection of Kidney Transplant Injury by Assessment of Donor-Derived Cell-free DNA via Massively Multiplex PCR. J Clin Med (2018) 8(1):19. 10.3390/jcm8010019

15.

BloomRDBrombergJSPoggioEDBunnapradistSLangoneAJSoodPet alCell-Free DNA and Active Rejection in Kidney Allografts. J Am Soc Nephrol (2017) 28(7):2221–32. 10.1681/ASN.2016091034

16.

RosenheckJPRossDJBotrosMWongASternbergJChenYAet alClinical Validation of a Plasma donor-derived Cell-free DNA Assay to Detect Allograft Rejection and Injury in Lung Transplant. Transpl Direct (2022) 8(4):e1317. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001317

17.

KimPJOlymbiosMSiuAWever PinzonOAdlerELiangNet alA Novel donor-derived Cell-free DNA Assay for the Detection of Acute Rejection in Heart Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl (2022) 41(7):919–27. 10.1016/j.healun.2022.04.002

18.

OellerichMSherwoodKKeownPSchützEBeckJStegbauerJet alLiquid Biopsies: Donor-Derived Cell-free DNA for the Detection of Kidney Allograft Injury. Nat Rev Nephrol (2021) 17(9):591–603. 10.1038/s41581-021-00428-0

19.

OellerichMBuddeKOsmanodjaBBornemann-KolatzkiKBeckJSchützEet alDonor-Derived Cell-free DNA as a Diagnostic Tool in Transplantation. Front Genet (2022) 13:1031894. 10.3389/fgene.2022.1031894

20.

AkifovaABuddeKAmannKBuettner-HeroldMChoiMOellerichMet alDonor-Derived Cell-free DNA Monitoring for Early Diagnosis of antibody-mediated Rejection After Kidney Transplantation: A Randomized Trial. Nephrol Dial Transpl (2025) 40(7):1384–95. 10.1093/ndt/gfae282

21.

Madill-ThomsenKSHidalgoLGDemkoZPGauthierPMPrewettALoweDet alDefining Relationships Among Tests for Kidney Transplant Antibody-Mediated Rejection. Kidney Int Rep (2025) 10(9):3225–38. 10.1016/j.ekir.2025.06.017

22.

Madill-ThomsenKSHidalgoLGMackovaMCampbellPDemkoZFeliusJet alDefining the Relationships Among Four Tests for Assessing antibody-mediated Rejection in Heart Transplants in a Prospective, Observational Study. J Heart Lung Transpl (2025). 10.1016/j.healun.2025.10.024

23.

OellerichMShipkovaMAsendorfTWalsonPDSchauerteVMettenmeyerNet alAbsolute Quantification of donor-derived Cell-free DNA as a Marker of Rejection and Graft Injury in Kidney Transplantation: Results from a Prospective Observational Study. Am J Transpl (2019) 19(11):3087–99. 10.1111/ajt.15416

24.

WhitlamJBLingLSkeneAKanellisJIerinoFLSlaterHRet alDiagnostic Application of Kidney allograft-derived Absolute Cell-free DNA Levels During Transplant Dysfunction. Am J Transpl (2019) 19(4):1037–49. 10.1111/ajt.15142

25.

BunnapradistSHomkrailasPAhmedEFehringerGBillingsPRTabrizianiH. Using Both the Fraction and Quantity of Donor-Derived Cell-free DNA to Detect Kidney Allograft Rejection. J Am Soc Nephrol (2021) 32(10):2439–41. 10.1681/ASN.2021050645

26.

HalloranPFReeveJMadill-ThomsenKSKaurNAhmedECantosCet alCombining donor-derived Cell-free DNA Fraction and Quantity to Detect Kidney Transplant Rejection Using Molecular Diagnoses and Histology as Confirmation. Transplantation (2022) 106(12):2435–42. 10.1097/TP.0000000000004212

27.

KimPJOlympiosMSiderisKTseliouETranTYCarterSet alA two-threshold Algorithm Using donor-derived Cell-free DNA Fraction and Quantity to Detect Acute Rejection After Heart Transplantation. Am J Transpl (2025) 25(9):1895–905. 10.1016/j.ajt.2025.04.021

28.

Ventura-AguiarPRamirez-BajoMJRoviraJBañón-ManeusEHierroNLazoMet alDonor-Derived Cell-free DNA Shows High Sensitivity for the Diagnosis of Pancreas Graft Rejection in Simultaneous Pancreas-kidney Transplantation. Transplantation (2022) 106(8):1690–7. 10.1097/TP.0000000000004088

29.

BrombergJSBunnapradistSSamaniego-PicotaMAnandSStitesEGauthierPet alElevation of Donor-derived Cell-free DNA Before Biopsy-proven Rejection in Kidney Transplant. Transplantation (2024) 108(9):1994–2004. 10.1097/TP.0000000000005007

30.

AltugYLiangNRamRRaviHAhmedEBrevnovMet alAnalytical Validation of a Single-nucleotide Polymorphism-based Donor-derived Cell-free DNA Assay for Detecting Rejection in Kidney Transplant Patients. Transplantation (2019) 103(12):2657–65. 10.1097/TP.0000000000002665

31.

LoupyAHaasMRoufosseCNaesensMAdamBAfrouzianMet alThe Banff 2019 Kidney Meeting Report (I): Updates on and Clarification of Criteria for T cell- and antibody-mediated Rejection. Am J Transpl (2020) 20(9):2318–31. 10.1111/ajt.15898

32.

DrachenbergCBBuettner-HeroldMAguiarPVHorsfieldCMikhailovAVPapadimitriouJCet alBanff 2022 Pancreas Transplantation Multidisciplinary Report: Refinement of Guidelines for T cell-mediated Rejection, antibody-mediated Rejection and Islet Pathology. Assessment of Duodenal Cuff Biopsies and Noninvasive Diagnostic Methods. Am J Transpl (2024) 24(3):362–79. 10.1016/j.ajt.2023.10.011

33.

StewartSWintersGLFishbeinMCTazelaarHDKobashigawaJAbramsJet alRevision of the 1990 Working Formulation for the Standardization of Nomenclature in the Diagnosis of Heart Rejection. J Heart Lung Transpl (2005) 24(11):1710–20. 10.1016/j.healun.2005.03.019

34.

DemetrisAJBellamyCHubscherSGO'LearyJRandhawaPSFengSet al2016 Comprehensive Update of the Banff Working Group on Liver Allograft Pathology: Introduction of Antibody-Mediated Rejection. Am J Transpl (2016) 16(10):2816–35. 10.1111/ajt.13909

35.

GohSKDoHTestroAPavlovicJVagoALokanJet alThe Measurement of Donor-Specific Cell-Free DNA Identifies Recipients with Biopsy-Proven Acute Rejection Requiring Treatment After Liver Transplantation. Transpl Direct (2019) 5(7):e462. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000902

36.

LevitskyJKandpalMGuoKKleiboekerSSinhaRAbecassisM. Donor-Derived Cell-free DNA Levels Predict Graft Injury in Liver Transplant Recipients. Am J Transpl (2022) 22(2):532–40. 10.1111/ajt.16835

37.

SchutzEFischerABeckJHardenMKochMWuenschTet alGraft-Derived Cell-free DNA, a Noninvasive Early Rejection and Graft Damage Marker in Liver Transplantation: A Prospective, Observational, Multicenter Cohort study. Plos Med (2017) 14(4):e1002286. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002286

38.

KeungNSandbergFSidlerDBanzVBerzigottiANgCKYet al (2025). Integrated Targeted Deep Sequencing Reveals Unique Tissue-Of-Origin And Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Signatures in Organ Transplant Recipients. medRxiv. 10.1101/2025.04.29.25326125

39.

MoellerCMOrenDFernandezVARubinsteinGLotanDMehlmanYet alClinical Utility of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA in Heart Transplant Recipients with Multi-Organ Transplants. Clin Transpl (2024) 38(10):e15479. 10.1111/ctr.15479

40.

ZakyZSCliffordSAFlemingJN. Diagnostic Performance of Gene Expression and dd-cfDNA in Multiorgan Transplant Recipients. Transpl Direct (2025) 11(3):e1772. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001772

41.

CareySATecsonKMJamilAKFeliusJWolf-DotyTKHallSA. Gene Expression Profiling Scores in Dual Organ Transplant Patients are Similar to Those in heart-only Recipients. Transpl Immunol (2018) 49:28–32. 10.1016/j.trim.2018.03.003

42.

ItagakiSToyodaNMossNManciniDEgorovaNMikamiTet alOutcomes of Simultaneous Heart and Kidney Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol (2023) 81(8):729–40. 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.053

43.

BenselerVTaySSBowenDGBertolinoP. Role of the Hepatic Parenchyma in Liver Transplant Tolerance: A Paradigm Revisited. Dig Dis (2011) 29(4):391–401. 10.1159/000329802

44.

RanaARoblesSRussoMJHalazunKJWoodlandDCWitkowskiPet alThe Combined Organ Effect: Protection Against Rejection?Ann Surg (2008) 248(5):871–9. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31817fc2b8

45.

TangJLigumskyLKWoodruffKJangCCharlandNAl Haj BaddarNet alA Novel Method to Estimate Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA in Pregnant Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Transpl Proc (2025) 57(5):706–12. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2025.03.025

46.

NorwitzERMcNeillGKalyanARiversEAhmedEMengLet alValidation of a Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism-Based Non-Invasive Prenatal Test in Twin Gestations: Determination of Zygosity, Individual Fetal Sex, and Fetal Aneuploidy. J Clin Med (2019) 8(7):937. 10.3390/jcm8070937

47.

SunKJiangPChanKCWongJChengYKYLiangRHSet alPlasma DNA Tissue Mapping by Genome-wide Methylation Sequencing for Noninvasive Prenatal, Cancer, and Transplantation Assessments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2015) 112(40):E5503–12. 10.1073/pnas.1508736112

Summary

Keywords

allograft rejection, dd-cfDNA, heart transplant, kidney translant, multi-organ transplant

Citation

Gupta G, Wojciechowski D, Sener A, Gong T, Dunn TB, Costa N, Odorico JS, Daloul R, Rohan VS, Biagini DG, Barnes D, Kaur N, Gude G, Ahmed E, Xie J, Spellicy CJ, Al Haj Baddar N, Bloom MS, Demko Z, Prewett A, Gauthier P, Bhorade S, Tabriziani H and Akkina SK (2026) Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA in Pancreas-Kidney, Heart-Kidney, and Liver-Kidney Multiorgan Transplant Recipients (MOTR). Transpl. Int. 38:15823. doi: 10.3389/ti.2025.15823

Received

30 October 2025

Revised

18 December 2025

Accepted

19 December 2025

Published

19 January 2026

Volume

38 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Gupta, Wojciechowski, Sener, Gong, Dunn, Costa, Odorico, Daloul, Rohan, Biagini, Barnes, Kaur, Gude, Ahmed, Xie, Spellicy, Al Haj Baddar, Bloom, Demko, Prewett, Gauthier, Bhorade, Tabriziani and Akkina.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gaurav Gupta, gaurav.gupta@vcuhealth.org

† Present address: Ty B. Dunn, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, United States Reem Daloul, Allegheny General Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.