Abstract

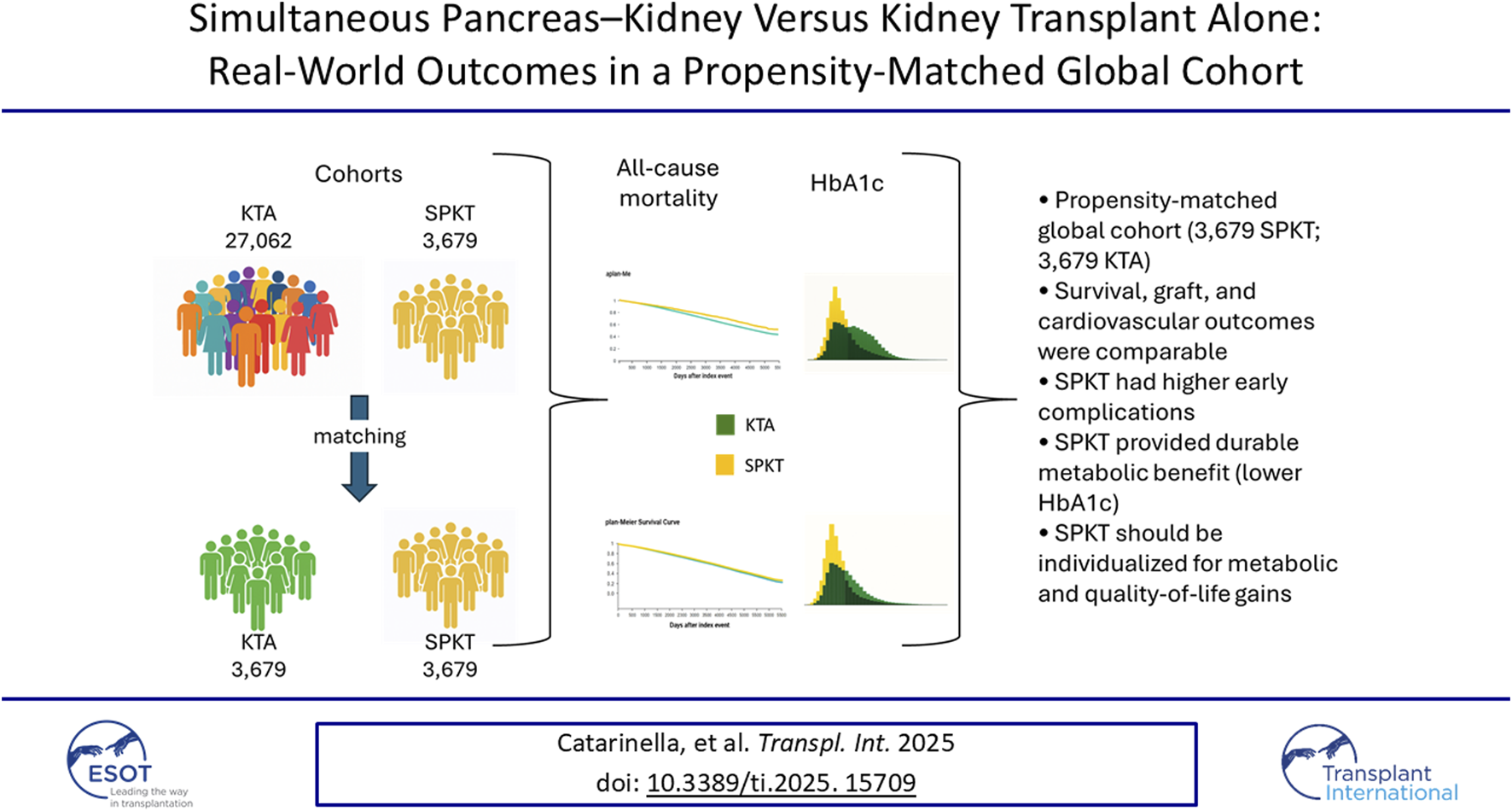

The true comparative effectiveness of simultaneous pancreas–kidney transplantation (SPKT) versus kidney transplantation alone (KTA) in patients with diabetes and end-stage renal disease remains incompletely defined. Using the TriNetX Global Collaborative Network (2010–2024), we identified 3,679 SPKT and 27,062 KTA recipients aged 18–59 years. In unmatched comparisons, SPKT recipients showed lower mortality, fewer cardiovascular events, and improved kidney graft survival relative to KTA recipients, but also higher early rejection, infection, and readmission rates. After 1:1 propensity score matching, the cohorts were well balanced across all measured covariates, and long-term estimates for survival (HR 1.00, 95% CI 0.90–1.10), kidney graft failure (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.94–1.04), and cardiovascular events (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.94–1.05) no longer differed over 10 years. In contrast, SPKT recipients maintained significantly lower HbA1c levels throughout follow-up (mean 6.2% vs. 6.6% at 5 years; p < 0.001), reflecting sustained physiologic glycaemic control and a high probability of insulin independence. Sensitivity analyses restricted to type 1 diabetes and non-obese recipients yielded consistent results. After accounting for measured differences between recipients, we did not detect a long-term survival advantage of SPKT over KTA, whereas durable metabolic benefits persisted. Because key donor and immunologic characteristics were not available, a modest intrinsic survival benefit cannot be excluded. These findings highlight the major role of patient selection and support individualised use of SPKT for metabolic indications and quality-of-life improvement rather than survival gain alone.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Simultaneous pancreas–kidney transplantation (SPKT) is a consolidated therapeutic option for patients with diabetes mellitus and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who are eligible for pancreas transplantation [1–3]. By replacing both organs simultaneously, SPKT provides restoration of renal function together with endogenous insulin secretion, offering the potential for insulin independence and durable metabolic control [4–7]. Kidney transplantation alone (KTA) remains the most common approach worldwide due to its broader applicability, lower surgical complexity, and higher availability of organs, but it does not address the underlying diabetes or its long-term complications [8]. The theoretical advantages of SPKT extend beyond kidney graft survival and patient longevity [9]. Normalization of glycaemic control after successful pancreas transplantation improves HbA1c and reduces glycaemic variability, thereby decreasing the risk of acute metabolic decompensation and potentially preventing or slowing the progression of microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes [10–15]. Several observational studies have suggested that SPKT recipients achieve superior metabolic outcomes and quality of life compared with patients undergoing KTA, who remain insulin-dependent and often face suboptimal glucose control despite advances in medical therapy [16]. Despite these potential benefits, the impact of SPKT on hard clinical outcomes has been debated. Some registry-based analyses and single-centre reports have described lower mortality and cardiovascular events among SPKT recipients [17–22], particularly in type 1 diabetes [23, 24], while others have failed to confirm a survival advantage once differences in baseline risk profiles are accounted for [25–30]. Moreover, SPKT carries higher perioperative morbidity, increased immunosuppression, and greater risk of early complications, raising concerns about the overall balance of risks and benefits [31–33]. In the recent era, with improvements in surgical techniques [34–36], perioperative care [37–40], immunosuppressive strategies [41–43], and diabetes management [44], it remains unclear whether the historical advantages of SPKT over KTA persist in real-world practice. Importantly, while survival and graft outcomes are critical endpoints, the ability of SPKT to provide superior long-term glycaemic control represents a distinctive and clinically meaningful outcome that may translate into downstream benefits for patients. Large-scale real-world data may help clarify these uncertainties. TriNetX, a federated network of healthcare organizations, aggregates longitudinal electronic health records and enables comparative effectiveness research across diverse populations with robust analytic tools, including propensity score methods to mitigate baseline imbalances [45]. The objective of this study was to compare long-term outcomes of SPKT versus KTA in patients with diabetes and ESRD using the TriNetX Global Collaborative Network. We evaluated survival, kidney and pancreas graft outcomes, cardiovascular events, diabetes-related acute and chronic complications, malignancies, and mental health, with a particular focus on whether the improved glycaemic control achieved by SPKT translates into clinical benefit in the new era of transplantation.

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Ethics

We performed a retrospective cohort study using the TriNetX Global Collaborative Network (2010–2024, access date 23 September 2025), which aggregates de-identified EHR data from >150 healthcare organizations worldwide. The network provides demographics, diagnoses, procedures, laboratory values, medications, and vitals. Data are de-identified per HIPAA and GDPR; institutional review board approval and informed consent were not required for analyses of de-identified data.

Study Population

Adults aged 18–59 years with diabetes and end-stage renal disease who underwent either simultaneous pancreas–kidney transplantation (SPKT) or kidney transplantation alone (KTA) were identified by transplant procedure codes. Exclusions: paediatric (<18 years) or older adults (>59 years), living-donor or multi-organ transplants, and records lacking a valid index date. The unmatched cohorts comprised 3,679 SPKT and 27,062 KTA recipients.

Exposure, Index Event and Follow-Up

The exposure was transplant type (SPKT vs. KTA). The index event was the date of transplantation. For survival analyses (Kaplan–Meier and Cox regression), outcomes were assessed from 90 days post-transplant. For fixed-timepoint estimates, 1-year outcomes were calculated including events from day 10 post-transplant, while 5- and 10-year outcomes were calculated including events from day 90 onwards.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were (i) all-cause mortality, (ii) kidney graft failure, and (iii) death-censored graft failure. Secondary outcomes included: major adverse kidney events (MAKE: dialysis dependence, eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2, transplant complications, or graft failure), transplant-related complications (ICD-10 T86.x), cardiovascular events (composite and components: acute myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, cardiac arrest, revascularization), infections/sepsis, treated acute rejection, 1-year hospital readmission, metabolic complications (hypoglycaemia; ketoacidosis/hyperosmolarity), microvascular complications (new-onset neuropathy; retinopathy), mental health (post-transplant depression/anxiety), and oncologic outcomes (PTLD/other neoplasms). Laboratory endpoints were most recent HbA1c and eGFR.

Detailed definitions of all outcomes, including the exact ICD-10 and procedure code lists used to define exposures, comorbidities and endpoints (e.g., cardiovascular events, rejection, infection, neuropathy), are provided in the Supplementary Methods. These definitions were pre-specified before any outcome analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Comparative analyses between cohorts were performed using risk difference, risk ratio, and odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals, as well as Kaplan–Meier curves with log-rank tests and Cox proportional hazards regression. Propensity score matching (1:1 nearest-neighbour with caliper 0.1) was applied to balance baseline demographic, clinical, and laboratory covariates. For all Cox models we assessed the proportional hazards assumption visually and using Schoenfeld residuals; no major violations were detected. Further details on cohort definitions, index event and time windows, analytic settings, outcome definitions (including ICD, CPT, and laboratory codes), and propensity score methodology are reported in the Supplementary Methods.

Result

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 3,679 SPKT and 27,062 KTA recipients were identified. Before matching, SPKT recipients were younger, more often type 1 diabetic, and carried fewer cardiovascular comorbidities, whereas KTA recipients were more frequently of Black or Hispanic ethnicity and more commonly had ischemic heart disease, heart failure, dyslipidaemia, and obesity (Supplementary Table S1). After 1:1 propensity score matching, well-balanced pairs were generated with excellent covariate balance (all SMD <0.1; Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Figures S1–S2). Median follow-up was ∼6 years in both groups. At the most recent assessment, HbA1c values were lower in SPKT compared with KTA recipients, both before matching (6.23% ± 1.68% vs. 7.11% ± 1.77%; p < 0.0001) and after matching (6.23% ± 1.68% vs. 6.58% ± 1.78%; p < 0.0001), although the difference was attenuated after adjustment. A similar pattern was seen for kidney function: eGFR was higher among SPKT recipients before matching (48.5 ± 29.3 vs. 44.1 ± 28.8 mL/min/1.73 m2; p < 0.0001), with only a modest residual difference after matching (48.5 ± 29.3 vs. 46.7 ± 29.0 mL/min/1.73 m2; p = 0.013).

Primary Outcomes

In the unmatched cohorts, SPKT recipients experienced significantly lower mortality compared with KTA, with hazard ratios well below unity and consistently favourable risk estimates at both 5 and 10 years (Table 1; Supplementary Tables S3–S4). Kaplan–Meier curves confirmed superior survival in SPKT (Figure 1). After propensity score matching, however, survival probabilities became virtually identical, and the risk of death did not differ between groups across all time points (Supplementary Tables S3–S4). Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier analysis suggested a modest advantage for SPKT, with lower cumulative incidence of graft loss over time (Table 1; Figure 1). However, risk estimates at 5 and 10 years indicated only minimal differences between groups, with relative risks close to unity (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). After propensity score matching, graft outcomes were fully comparable, with no evidence of a significant difference at any time point (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). In contrast, death-censored analyses showed less favourable outcomes for SPKT. In the unmatched population, the risk of death-censored graft failure was slightly higher in SPKT, particularly in the early post-transplant period, with relative risks favouring KTA (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). Kaplan–Meier curves showed largely overlapping trajectories (Figure 1). After matching, the differences disappeared, with similar risks of death-censored graft loss between groups (Table 1; Supplementary Tables S3, S4).

TABLE 1

| Outcome | Cohort | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | KM log-rank p | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | PS-matched | 1.00 (0.91–1.11) | 0.97 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 0.76 (0.71–0.83) | <0.001 | Favors SPKT | |

| Kidney graft failure | PS-matched | 0.97 (0.91–1.04) | 0.38 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) | 0.001 | Favors SPKT | |

| Death-censored graft failure | PS-matched | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) | 0.79 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | 0.11 | Neutral | |

| MAKE | PS-matched | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) | 0.10 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 0.82 (0.79–0.85) | <0.001 | Favors SPKT | |

| Post-transplant cardiovascular events | PS-matched | 0.98 (0.91–1.05) | 0.55 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 0.73 (0.69–0.77) | <0.001 | Favors SPKT | |

| Treated acute rejection | PS-matched | 1.02 (0.95–1.11) | 0.57 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 1.16 (1.09–1.23) | <0.001 | Favors KTA | |

| Acute myocardial infarction (first event) | PS-matched | 1.09 (0.94–1.25) | 0.26 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 0.89 (0.80–0.99) | 0.04 | Favors SPKT | |

| Heart failure (first event) | PS-matched | 0.94 (0.84–1.05) | 0.25 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) | <0.001 | Favors SPKT | |

| Stroke (first event) | PS-matched | 1.05 (0.87–1.25) | 0.63 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 0.87 (0.76–1.00) | 0.05 | Favors SPKT | |

| Infection or sepsis | PS-matched | 1.00 (0.92–1.08) | 0.98 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 0.87 (0.82–0.93) | <0.001 | Favors SPKT | |

| Hypoglycaemia | PS-matched | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) | 0.93 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 0.89 (0.81–0.97) | 0.01 | Favors SPKT | |

| Ketoacidosis/hyperosmolarity | PS-matched | 0.95 (0.83–1.09) | 0.50 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 1.20 (1.08–1.33) | 0.001 | Favors KTA | |

| Depression/Anxiety onset post-Tx | PS-matched | 0.99 (0.89–1.11) | 0.87 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) | 0.13 | Neutral | |

| Diabetic neuropathy (new onset) | PS-matched | 1.11 (0.99–1.24) | 0.06 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 1.04 (0.96–1.14) | 0.31 | Neutral | |

| Diabetic retinopathy (new onset) | PS-matched | 1.06 (0.93–1.20) | 0.38 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 1.11 (1.00–1.22) | 0.04 | Favors KTA | |

| PTLD/Neoplasm | PS-matched | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 0.87 | Neutral |

| Pre-matching | 0.95 (0.88–1.01) | 0.11 | Neutral |

Longitudinal outcomes (Kaplan–Meier and Cox models): SPKT vs. KTA.

Abbreviations. SPKT, simultaneous pancreas–kidney transplant; KTA, kidney transplant alone; KM, Kaplan–Meier; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; PS-matched, propensity-score matched; MAKE, major adverse kidney events; PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder.

FIGURE 1

Kaplan–Meier survival curves and hazard ratios for SPKT versus KTA. (A) Kaplan–Meier estimates are shown for patient survival, overall graft survival, death-censored graft survival, and cardiovascular outcomes (major adverse cardiovascular events, myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure), comparing simultaneous pancreas–kidney transplantation (SPKT, purple) and kidney transplant alone (KTA, light blue). Curves are presented for unmatched cohorts (left column) and after 1:1 propensity score matching (right column). Follow-up extended up to 10 years. (B) The forest plot summarizes hazard ratios (HR, dots) with 95% confidence intervals (bars) for each outcome, calculated at prespecified timepoints (1, 5, and 10 years) in unmatched (red) and matched (blue) populations. HR values <1 indicate lower risk with SPKT, whereas HR values >1 indicate lower risk with KTA.

Secondary Outcomes

A consistent pattern was observed across early peri-transplant endpoints. In the unmatched cohorts, SPKT recipients had higher rates of treated acute rejection, kidney transplant–related complications, and hospital readmission within the first year, all favouring KTA (Supplementary Tables S2–S4). After propensity score matching, the excess risk of acute rejection was no longer significant, whereas kidney transplant complications remained more frequent in SPKT, though with reduced effect sizes (Supplementary Tables S3-S4). Conversely, major adverse kidney events (MAKE) consistently favoured SPKT before adjustment, with hazard ratios and relative risks below unity across all time horizons (Table 1; Supplementary Tables S2–S4). After propensity score matching, however, this advantage was limited to the first post-transplant year, with neutral risks thereafter (Supplementary Table S2). In the unmatched cohorts, SPKT recipients showed lower risks of post-transplant cardiovascular events, with the advantage predominantly driven by a reduced incidence of heart failure (Table 1; Supplementary Tables S3–S4). Myocardial infarction and stroke occurred less frequently in SPKT as well, but the effect size was smaller. Kaplan–Meier analyses confirmed fewer cumulative cardiovascular events in SPKT, largely attributable to the divergence in heart failure risk (Figure 1). After propensity score matching, however, all differences were attenuated, and risks for the composite endpoint as well as for myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure became comparable between SPKT and KTA (Supplementary Tables S2–S4). In the unmatched cohorts, the profile of diabetes-related events was mixed. Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar states were more frequent in SPKT, with relative risks favouring KTA (Supplementary Tables S3–S4). By contrast, severe hypoglycaemia occurred less often in SPKT, indicating a modest advantage for SPKT in this acute complication (Supplementary Tables S3–S4). For chronic complications, new-onset diabetic neuropathy and retinopathy were more frequent in SPKT, with risk estimates favouring KTA (Supplementary Tables S3–S4). After propensity score matching, however, all these differences were attenuated, and risks of acute decompensation, hypoglycaemia, neuropathy, and retinopathy became largely comparable between groups (Supplementary Tables S2–S4). Patterns of infection and sepsis varied according to the time horizon. In the unmatched cohorts, Kaplan–Meier estimates suggested slightly lower cumulative infection risk in SPKT over long-term follow-up (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). In contrast, early events within the first year were more common in SPKT, favouring KTA. After propensity score matching, the survival curves became largely overlapping, but the excess of early infections in SPKT persisted, while long-term risks converged toward neutrality (Supplementary Table S2). The incidence of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease and other neoplasms was consistently similar between SPKT and KTA, both before and after adjustment (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). As a proxy of quality of life, new-onset depression or anxiety was slightly less frequent in KTA before matching, but this apparent difference was not confirmed after adjustment. In the matched cohorts, risks were virtually identical (Neutral; Supplementary Tables S2–S4).

Sensitivity Analyses

To assess the robustness of our findings, we repeated all analyses in two restricted subgroups: (i) recipients with a primary diagnosis of type 1 diabetes (Supplementary Table S5), and (ii) type 1 diabetes recipients with a body mass index <30 kg/m2 at the time of transplantation (Supplementary Table S6). Across both sensitivity analyses, the direction and magnitude of risk estimates were consistent with those observed in the overall study population.

Discussion

In this large, real-world analysis, SPKT recipients achieved consistently better glycaemic control than KTA recipients, as reflected by lower HbA1c levels both before and after propensity score matching. Despite this clear metabolic advantage, long-term patient survival, kidney graft survival, and cardiovascular outcomes were indistinguishable between SPKT and KTA once baseline differences were accounted for. The initial signals of improved survival and reduced cardiovascular risk in the unmatched cohorts were largely attributable to selection bias, with SPKT recipients being younger, predominantly affected by type 1 diabetes, and carrying fewer comorbidities at baseline. Importantly, SPKT was associated with higher early risks—including treated acute rejection, hospital readmission, perioperative complications, and infection/sepsis within the first post-transplant year. These excess short-term risks did not translate into inferior long-term outcomes. The only remaining clinical difference was a modest reduction in MAKE during the first post-transplant year, suggesting a possible short-term renoprotective effect of improved glycaemic control, although without sustained long-term impact on major endpoints. Our findings differ from the earliest registry-based and single-centre reports, which consistently suggested a survival and cardiovascular advantage of SPKT over KTA [46–49] particularly among younger recipients with type 1 diabetes [7, 21, 47, 49–51]. However, they align more closely with subsequent analyses that applied more comprehensive multivariable adjustment or propensity-based methods and reported attenuation or disappearance of these differences [25, 52, 53]. This pattern supports the interpretation that much of the apparent survival benefit of SPKT in historical cohorts may have reflected differences in recipient selection, donor quality, and the clinical context of earlier eras.

A notable result from our study is the persistently lower HbA1c observed in SPKT recipients after matching, despite the relatively small absolute difference (6.2% vs. 6.6%). Based on landmark trials such as DCCT/EDIC [54] and UKPDS [54], a 1% reduction in HbA1c corresponds to a 15%–20% reduction in microvascular risk and a 10%–15% reduction in cardiovascular events. Accordingly, the 0.3%–0.4% difference in our study would be expected to confer only a 4%–6% reduction in microvascular risk and a 3%–5% reduction in cardiovascular risk—an effect size insufficient to produce detectable long-term differences in survival or major cardiovascular outcomes in heterogeneous, real-world cohorts. This helps explain why improved glycaemic control after SPKT, while clinically relevant, did not translate into measurable survival advantages at a population level. These short-term risks associated with SPKT—including perioperative morbidity, treated rejection, infections, and early hospital readmissions—are well documented [31, 32, 36, 55, 56] and represent a recognised trade-off against the metabolic benefits. Furthermore, the therapeutic landscape has evolved substantially. Advances in continuous glucose monitoring, automated insulin delivery systems, and the availability of new agents such as SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists have markedly improved glycaemic profiles and cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes after kidney transplantation. These innovations have likely narrowed the incremental advantage of SPKT over KTA, further contextualising our findings of long-term similarity in hard outcomes.

This finding warrants further clinical interpretation. In SPKT recipients, an HbA1c in the low-to-mid 6% range reflects physiological insulin secretion, typically associated with minimal risk of severe hypoglycaemia and lower glycaemic variability. In contrast, similar HbA1c values in insulin-treated KTA recipients may mask substantial hypoglycaemia burden, glycaemic fluctuations, and the cognitive and emotional load of intensive insulin management. Because our dataset did not include continuous glucose monitoring metrics—such as time-in-range, glucose excursion indices, or asymptomatic hypoglycaemia—the true metabolic benefit of SPKT is likely underestimated. These considerations reinforce that the metabolic advantage of SPKT remains clinically meaningful even in the absence of detectable long-term survival differences. Our findings should also be interpreted in the context of prior evidence, which for decades has consistently shown a survival advantage of SPKT over KTA. Several factors likely explain why our real-world findings differ from these earlier observations. First, historical cohorts reflect an era of higher dialysis mortality and less effective diabetes and cardiovascular management. Second, donor and recipient selection practices have evolved: SPKT recipients typically receive younger, lower-risk organs and enter transplantation earlier in the course of diabetic complications, whereas KTA recipients accumulate greater comorbidity and longer pre-transplant dialysis exposure. These factors likely amplified earlier survival signals. Third, improvements in perioperative care, modern immunosuppression, and cardiovascular therapy have narrowed the survival gap. Finally, because our dataset lacked key transplant-specific variables—such as donor quality indices, HLA matching, cold ischaemia time, and immunosuppression—an intrinsic survival benefit of SPKT cannot be excluded and may be masked by unmeasured confounding. Together, these considerations reconcile our findings with the broader literature and suggest that, in current practice, the dominant advantage of SPKT lies in its metabolic and quality-of-life benefits rather than in large differences in long-term survival.

This study has several important limitations First, despite rigorous propensity score matching, residual confounding is unavoidable because the TriNetX platform lacks key transplant-specific variables. Donor quality metrics such as Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) and Pancreas Donor Risk Index (PDRI), which strongly influence kidney outcomes and differ systematically between SPKT and KTA, were not available. Similarly, no information was provided on HLA matching, panel reactive antibodies, donor-specific antibodies, cold ischaemia time, centre experience or detailed immunosuppression protocols. These unmeasured factors may attenuate or obscure a true intrinsic survival benefit of SPKT or, conversely, magnify early procedural risk. Second, exposures, comorbidities and outcomes were identified using ICD-10 and procedure codes. The complete lists of codes used in this study are provided in the Supplementary Methods. Although these coding-based definitions follow established conventions, they remain prone to misclassification, under-reporting and variability across institutions—particularly for complex outcomes such as cardiovascular events, rejection, infection or neuropathy, for which clinical adjudication would be preferable. Third, the database does not capture patient-reported outcomes, continuous glucose monitoring metrics or hypoglycaemia burden—elements that represent the most meaningful clinical benefits of SPKT for many patients [57, 58]. As a result, the metabolic advantage observed in this study likely underestimates the full quality-of-life impact of successful pancreas transplantation [59, 60]. Fourth, diabetes type was defined using diagnosis codes, which may misclassify insulin-treated type 2 diabetes as type 1. Although sensitivity analyses restricted to patients coded as type 1 diabetes and to non-obese recipients were performed, some residual misclassification may persist. Finally, because SPKT by definition requires a deceased donor, our comparison group included only deceased-donor KTA recipients. These findings cannot be extrapolated to living-donor kidney transplantation, which often provides superior survival and represents a distinct clinical pathway.

Taken together, these limitations suggest that while our findings demonstrate no detectable long-term survival advantage of SPKT after adjustment for measured variables, a modest true benefit cannot be excluded. Rather, our results underscore the extent to which survival outcomes are shaped by patient selection, donor quality, and centre-level variation. In this context, the principal justification for SPKT in contemporary practice lies in its profound metabolic and quality-of-life benefits, balanced against higher early procedural risks.

In summary, this large, contemporary real-world analysis shows that the apparent survival advantage of SPKT over KTA disappears after balancing for measurable clinical covariates. Because donor quality and other key transplant-specific factors were not captured, a residual survival benefit cannot be excluded. Nevertheless, SPKT provides durable metabolic benefits, including excellent glycaemic control and freedom from insulin. In the setting of comparable observed survival, decisions about SPKT should be individualised, considering each patient’s preference for insulin independence, glycaemic stability, and quality-of-life improvement, as well as willingness to accept higher short-term risks. These findings also highlight a broader issue: despite clear metabolic and quality-of-life benefits, SPKT remains underutilised, and many eligible patients are not systematically referred to transplant centres. Variability in referral pathways, limited awareness among non-transplant clinicians, and the absence of structured evaluation frameworks likely prevent equitable access. In light of our results—showing that the decision for SPKT increasingly centres on metabolic benefit and patient preference—timely and systematic referral becomes critical. Strengthening referral pathways and enhancing collaboration between diabetologists, nephrologists, and transplant teams will be essential to ensure that all suitable candidates are appropriately evaluated.

Statements

Data availability statement

Individual participant data will not be made available. Study protocol, statistical analysis plan, and analytical code will be available from the time of publication in response to any reasonable request addressed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LP conceived and supervised the study, had full access to all data, and takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the analyses. DC and LP performed the data extraction and statistical analyses. FR, SW, RC, and DC contributed to study design, data interpretation, and manuscript drafting. All authors contributed to the conception, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

FR and SW were employed by TriNetX at the time of the study.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ti.2025.15709/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S1Standardized mean differences (SMD) for baseline characteristics between SPKT and KTA recipients before (red circles) and after propensity score matching (blue squares). Variables include demographics, comorbidities, and diabetes type. Dashed vertical lines at ±0.1 indicate the threshold for acceptable balance. Matching achieved excellent covariate balance across all variables, with all post-matching SMDs <0.1.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S2Distribution of propensity scores, follow-up time, HbA1c, and eGFR before and after matching. The figure displays cumulative distribution curves of propensity scores (top panels), histograms of follow-up time (middle panels), and histograms of last available laboratory values for HbA1c (bottom left) and eGFR (bottom right) in SPKT and KTA recipients, shown separately for unmatched and propensity score–matched cohorts.

Abbreviations

AR, absolute risk; CI, confidence interval; DDKT, deceased donor kidney transplantation; EHR, electronic health records; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HR, hazard ratio; KTA, kidney transplantation alone; KM, Kaplan–Meier; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MAKE, major adverse kidney events; OR, odds ratio; PS-matched, propensity score–matched; PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder; RD, risk difference; RR, relative risk; SMD, standardized mean difference; SPKT, simultaneous pancreas–kidney transplantation; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

References

1.

Boggi U Vistoli F Andres A Arbogast HP Badet L Baronti W et al First World Consensus Conference on Pancreas Transplantation: Part Ii–Recommendations. Am J Transplant (2021) 21:17–59. 10.1111/ajt.16750

2.

Kandaswamy R Stock PG Miller JM Handarova D Israni AK Snyder JJ . Optn/Srtr 2023 Annual Data Report: Pancreas. Am J Transpl (2025) 25(2s1):S138–s92. 10.1016/j.ajt.2025.01.021

3.

Perosa M Branez JR Danziere FR Zeballos B Mota LT Vidigal AC et al Over 1000 Pancreas Transplants in a Latin American Program. Transplantation (2025) 109:e656–e665. 10.1097/tp.0000000000005421

4.

Fridell JA Stratta RJ . Modern Indications for Referral for Kidney and Pancreas Transplantation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens (2023) 32(1):4–12. 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000846

5.

Choksi H Pleass H Robertson P Au E Rogers N . Long-Term Metabolic Outcomes Post-Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation in Recipients with Type 1 Diabetes. Transplantation (2025) 109(7):1222–9. 10.1097/tp.0000000000005334

6.

Fridell JA Stratta RJ Gruessner AC . Pancreas Transplantation: Current Challenges, Considerations, and Controversies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2023) 108(3):614–23. 10.1210/clinem/dgac644

7.

Hau HM Jahn N Brunotte M Lederer AA Sucher E Rasche FM et al Short and Long-Term Metabolic Outcomes in Patients with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Receiving a Simultaneous Pancreas Kidney Allograft. BMC Endocr Disord (2020) 20(1):30. 10.1186/s12902-020-0506-9

8.

Kaballo MA Canney M O’Kelly P Williams Y O’Seaghdha CM Conlon PJ . A Comparative Analysis of Survival of Patients on Dialysis and After Kidney Transplantation. Clin Kidney Journal (2018) 11(3):389–93. 10.1093/ckj/sfx117

9.

Smets YF Westendorp RG van der Pijl JW de Charro FT Ringers J de Fijter JW et al Effect of Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation on Mortality of Patients with Type-1 Diabetes Mellitus and End-Stage Renal Failure. Lancet (1999) 353(9168):1915–9. 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07513-8

10.

La RE Fiorina P Di Carlo V Astorri E Rossetti C Lucignani G et al Cardiovascular Outcomes After Kidney–Pancreas and Kidney–Alone Transplantation. Kidney International (2001) 60(5):1964–71. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00008.x

11.

Fiorina P La Rocca E Venturini M Minicucci F Fermo I Paroni R et al Effects of Kidney-Pancreas Transplantation on Atherosclerotic Risk Factors and Endothelial Function in Patients with Uremia and Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes (2001) 50(3):496–501. 10.2337/diabetes.50.3.496

12.

Luan FL Miles CD Cibrik DM Ojo AO . Impact of Simultaneous Pancreas and Kidney Transplantation on Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Transplantation (2007) 84(4):541–4. 10.1097/01.tp.0000270617.43811.af

13.

Dmitriev IV Severina AS Zhuravel NS Yevloyeva MI Salimkhanov RK Shchelykalina SP et al Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Patients Following Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation: Time in Range and Glucose Variability. Diagnostics (Basel) (2023) 13(9):Epub 20230430. 10.3390/diagnostics13091606

14.

Montagud-Marrahi E Molina-Andújar A Pané A Ruiz S Amor AJ Esmatjes E et al Impact of Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation on Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Diabetes. Transplantation (2022) 106(1):158–66. 10.1097/tp.0000000000003710

15.

Scialla JJ . Choices in Kidney Transplantation in Type 1 Diabetes: Are There Skeletal Benefits of the Endocrine Pancreas?Kidney Int (2013) 83(3):356–8. 10.1038/ki.2012.438

16.

Fridell JA Powelson JA . Pancreas After Kidney Transplantation: Why Is the Most Logical Option the Least Popular?Curr Opinion Organ Transplantation (2015) 20(1):108–14. 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000160

17.

Sollinger HW Odorico JS Knechtle SJ D'Alessandro AM Kalayoglu M Pirsch JD . Experience with 500 Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplants. Ann Surgery (1998) 228(3):284–96. 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00002

18.

Sucher R Rademacher S Jahn N Brunotte M Wagner T Alvanos A et al Effects of Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation and Kidney Transplantation Alone on the Outcome of Peripheral Vascular Diseases. BMC Nephrol (2019) 20(1):453. 10.1186/s12882-019-1649-7

19.

Hedley JA Kelly PJ Webster AC . Patient and Kidney Transplant Survival in Type 1 Diabetics After Kidney Transplant Alone Compared to Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplant. ANZ J Surg (2022) 92(7-8):1856–62. 10.1111/ans.17663

20.

Reddy KS Stablein D Taranto S Stratta RJ Johnston TD Waid TH et al Long-Term Survival Following Simultaneous Kidney-Pancreas Transplantation Versus Kidney Transplantation Alone in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Renal Failure. Am J Kidney Dis (2003) 41(2):464–70. 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50057

21.

Lange UG Rademacher S Zirnstein B Sucher R Semmling K Bobbert P et al Cardiovascular Outcomes After Simultaneous Pancreas Kidney Transplantation Compared to Kidney Transplantation Alone: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. BMC Nephrol (2021) 22(1):347. 10.1186/s12882-021-02522-8

22.

Mohan P Safi K Little DM Donohoe J Conlon P Walshe JJ et al Improved Patient Survival in Recipients of Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplant Compared with Kidney Transplant Alone in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and End-Stage Renal Disease. Br J Surg (2003) 90(9):1137–41. 10.1002/bjs.4208

23.

Morath C Zeier M Döhler B Schmidt J Nawroth PP Schwenger V et al Transplantation of the Type 1 Diabetic Patient: The Long-Term Benefit of a Functioning Pancreas Allograft. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol (2010) 5(3):549–52. 10.2215/cjn.03720609

24.

Chetboun M Masset C Maanaoui M Defrance F Gmyr V Raverdy V et al Primary Graft Function and 5 Year Insulin Independence After Pancreas and Islet Transplantation for Type 1 Diabetes: A Retrospective Parallel Cohort Study. Transpl Int (2023) 36:11950. 10.3389/ti.2023.11950

25.

Sung RS Zhang M Schaubel DE Shu X Magee JC . A Reassessment of the Survival Advantage of Simultaneous Kidney-Pancreas Versus Kidney-Alone Transplantation. Transplantation (2015) 99(9):1900–6. 10.1097/tp.0000000000000663

26.

Ziaja J Kolonko A Kamińska D Chudek J Owczarek AJ Kujawa-Szewieczek A et al Long-Term Outcomes of Kidney and Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation in Recipients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: Silesian Experience. Transpl Proc (2016) 48(5):1681–6. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.01.082

27.

Barlow AD Saeb-Parsy K Watson CJE . An Analysis of the Survival Outcomes of Simultaneous Pancreas and Kidney Transplantation Compared to Live Donor Kidney Transplantation in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes: A Uk Transplant Registry Study. Transpl Int (2017) 30(9):884–92. 10.1111/tri.12957

28.

Wiseman AC Gralla J . Simultaneous Pancreas Kidney Transplant Versus Other Kidney Transplant Options in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol (2012) 7(4):656–64. 10.2215/cjn.08310811

29.

Weiss AS Smits G Wiseman AC . Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Versus Deceased Donor Kidney Transplant: Can a Fair Comparison Be Made?Transplantation (2009) 87(9):1402–10. 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a276fd

30.

Douzdjian V Abecassis MM Corry RJ Hunsicker LG . Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Versus Kidney-Alone Transplants in Diabetics: Increased Risk of Early Cardiac Death and Acute Rejection Following Pancreas Transplants. Clin Transpl (1994) 8(3 Pt 1):246–51. 10.1111/j.1399-0012.1994.tb00248.x

31.

King EA Kucirka LM McAdams-DeMarco MA Massie AB Al Ammary F Ahmed R et al Early Hospital Readmission After Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation: Patient and Center-Level Factors. Am J Transpl (2016) 16(2):541–9. 10.1111/ajt.13485

32.

Vidal CN López Cubillana P López González PA Alarcón CM Hernández JR Martínez LA et al Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation: Early Complications and Long-Term Outcomes - a Single-Center Experience. Can Urol Assoc J (2022) 16(7):E357–e62. 10.5489/cuaj.7635

33.

Kaku K Okabe Y Kubo S Sato Y Mei T Noguchi H et al Utilization of the Pancreas from Donors with an Extremely High Pancreas Donor Risk Index: Report of the National Registry of Pancreas Transplantation. Transpl Int (2023) 36:11132. 10.3389/ti.2023.11132

34.

Vianna R Morsi M Munoz-Abraham AS González J Ciancio G . Robotic-Assisted Simultaneous Kidney-Pancreas Transplantation (Raspkt) Without Hand Assistance: A Retrospective Cohort Study Showing a Paradigm Shift in Minimally Invasive Transplant Surgery. Surgery (2025) 186:109587. 10.1016/j.surg.2025.109587

35.

Spaggiari M Martinino A Petrochenkov E Bencini G Zhang JC Cardoso VR et al Single-Center Retrospective Assessment of Robotic-Assisted Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplants: Exploring Clinical Utility. Am J Transpl (2024) 24(6):1035–45. 10.1016/j.ajt.2023.12.021

36.

Ray S Hobeika C Norgate A Sawicka Z Schiff J Sapisochin G et al Evolving Trends in the Management of Duodenal Leaks After Pancreas Transplantation: A Single-Centre Experience. Transpl Int (2024) 37:13302. 10.3389/ti.2024.13302

37.

Ai LE Farrokhi K Zhang MY Offerni J Luke PP Sener A . Heparin Thromboprophylaxis in Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Transpl Int (2023) 36:10442. 10.3389/ti.2023.10442

38.

Sharda B Jay CL Gurung K Harriman D Gurram V Farney AC et al Improved Surgical Outcomes Following Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation in the Contemporary Era. Clin Transpl (2022) 36(11):e14792. 10.1111/ctr.14792

39.

Ahopelto K Bonsdorff A Grasberger J Lempinen M Nordin A Helanterä I et al Pasireotide Versus Octreotide in Preventing Complications After Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation. Transpl Int (2023) 36:11255. 10.3389/ti.2023.11255

40.

Petruzzo P Ye H Sardu C Rouvière O Buron F Crozon-Clauzel J et al Pancreatic Allograft Thrombosis: Implementation of the Cpat-Grading System in a Retrospective Series of Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation. Transpl Int (2023) 36:11520. 10.3389/ti.2023.11520

41.

Müller MM Schwaiger E Kurnikowski A Haidinger M Ristl R Tura A et al Glucose Metabolism After Kidney Transplantation: Insulin Release and Sensitivity with Tacrolimus- Versus Belatacept-based Immunosuppression. Am J Kidney Dis (2021) 77(3):462–4. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.07.016

42.

Swaab TDA Pol RA Crop MJ Sanders JF Berger SP Hofker HS et al Short-Term Outcome After Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation With Alemtuzumab Vs. Basiliximab Induction: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Sci Rep (2025) 15(1):20732. 10.1038/s41598-025-06750-y

43.

Cerise A Shaker T LeNguyen P Dinesh A Jackson S Kandaswamy R et al Recipient and Graft Outcomes in Simultaneous Kidney and Pancreas Transplantation with Steroid Avoidance in the United States. Transplantation (2023) 107(2):521–8. 10.1097/tp.0000000000004295

44.

Lo C Toyama T Oshima M Jun M Chin KL Hawley CM et al Glucose-Lowering Agents for Treating Pre-Existing and New-Onset Diabetes in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2020) 8(8):Cd009966. 10.1002/14651858.CD009966.pub3

45.

Ludwig RJ Anson M Zirpel H Thaci D Olbrich H Bieber K et al A Comprehensive Review of Methodologies and Application to Use the Real-World Data and Analytics Platform Trinetx. Front Pharmacol (2025) 16:1516126. 10.3389/fphar.2025.1516126

46.

Sollinger HW Odorico JS Becker YT D'Alessandro AM Pirsch JD . One Thousand Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplants at a Single Center with 22-Year Follow-Up. Ann Surgery (2009) 250(4):618–30. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b76d2b

47.

Esmeijer K Hoogeveen EK van den Boog PJM Konijn C Mallat MJK Baranski AG et al Superior Long-Term Survival for Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation as Renal Replacement Therapy: 30-Year Follow-up of a Nationwide Cohort. Diabetes Care (2020) 43(2):321–8. 10.2337/dc19-1580

48.

Lindahl JP Hartmann A Horneland R Holdaas H Reisæter AV Midtvedt K et al Improved Patient Survival with Simultaneous Pancreas and Kidney Transplantation in Recipients with Diabetic End-Stage Renal Disease. Diabetologia (2013) 56(6):1364–71. 10.1007/s00125-013-2888-y

49.

Cao Y Liu X Lan X Ni K Li L Fu Y . Simultaneous Pancreas and Kidney Transplantation for End-Stage Kidney Disease Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg (2022) 407(3):909–25. 10.1007/s00423-021-02249-y

50.

Fu Y Cao Y Wang H Zhao J Wang Z Mo C et al Metabolic Outcomes and Renal Function After Simultaneous Kidney/Pancreas Transplantation Compared with Kidney Transplantation Alone for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Transpl Int (2021) 34(7):1198–211. 10.1111/tri.13892

51.

Yiannoullou P Summers A Goh SC Fullwood C Khambalia H Moinuddin Z et al Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events Following Simultaneous Pancreas and Kidney Transplantation in the United Kingdom. Diabetes Care (2019) 42(4):665–73. 10.2337/dc18-2111

52.

Ji M Wang M Hu W Ibrahim M Lentine KL Merzkani M et al Survival After Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation in Type 1 Diabetes: The Critical Role of Early Pancreas Allograft Function. Transpl Int (2022) 35:10618. 10.3389/ti.2022.10618

53.

Alhamad T Kunjal R Wellen J Brennan DC Wiseman A Ruano K et al Three-Month Pancreas Graft Function Significantly Influences Survival Following Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Am J Transpl (2020) 20(3):788–96. 10.1111/ajt.15615

54.

Stratton IM Adler AI Neil HA Matthews DR Manley SE Cull CA et al Association of Glycaemia with Macrovascular and Microvascular Complications of Type 2 Diabetes (Ukpds 35): Prospective Observational Study. BMJ (2000) 321(7258):405–12. 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405

55.

Grasberger J Ortiz F Ekstrand A Sallinen V Ahopelto K Finne P et al Infection-Related Hospitalizations After Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation Compared to Kidney Transplantation Alone. Transpl Int (2024) 37:12235. 10.3389/ti.2024.12235

56.

Kandaswamy R Stock PG Miller JM White J Booker SE Israni AK et al Optn/Srtr 2021 Annual Data Report: Pancreas. Am J Transpl (2023) 23(2 Suppl. 1):S121–s77. 10.1016/j.ajt.2023.02.005

57.

Dunn TB . Life After Pancreas Transplantation: Reversal of Diabetic Lesions. Curr Opinion Organ Transplantation (2014) 19(1):73–9. 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000045

58.

McCune K Owen‐Simon N Dube GK Ratner LE . The Best Insulin Delivery Is a Human Pancreas. Clin Transplant (2023) 37(4):e14920. 10.1111/ctr.14920

59.

Romano TM Linhares MM Posegger KR Rangel ÉB Gonzalez AM Salzedas-Netto AA et al Evaluation of Psychological Symptoms in Patients Before and After Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation: A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Acta Cir Bras (2022) 37(2):e370202. 10.1590/acb370202

60.

Shingde R Calisa V Craig JC Chapman JR Webster AC Pleass H et al Relative Survival and Quality of Life Benefits of Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation, Deceased Kidney Transplantation and Dialysis in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus-a Probabilistic Simulation Model. Transpl Int (2020) 33(11):1393–404. 10.1111/tri.13679

Summary

Keywords

simultaneous pancreas–kidney transplantation, kidney transplantation, diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, patient survival

Citation

Catarinella D, Williford S, Rusconi F, Caldara R and Piemonti L (2025) Simultaneous Pancreas–Kidney Versus Kidney Transplant Alone: Real-World Outcomes in a Propensity-Matched Global Cohort. Transpl. Int. 38:15709. doi: 10.3389/ti.2025.15709

Received

08 October 2025

Revised

13 November 2025

Accepted

16 December 2025

Published

30 December 2025

Volume

38 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Catarinella, Williford, Rusconi, Caldara and Piemonti.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lorenzo Piemonti, piemonti.lorenzo@hsr.it

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.