Abstract

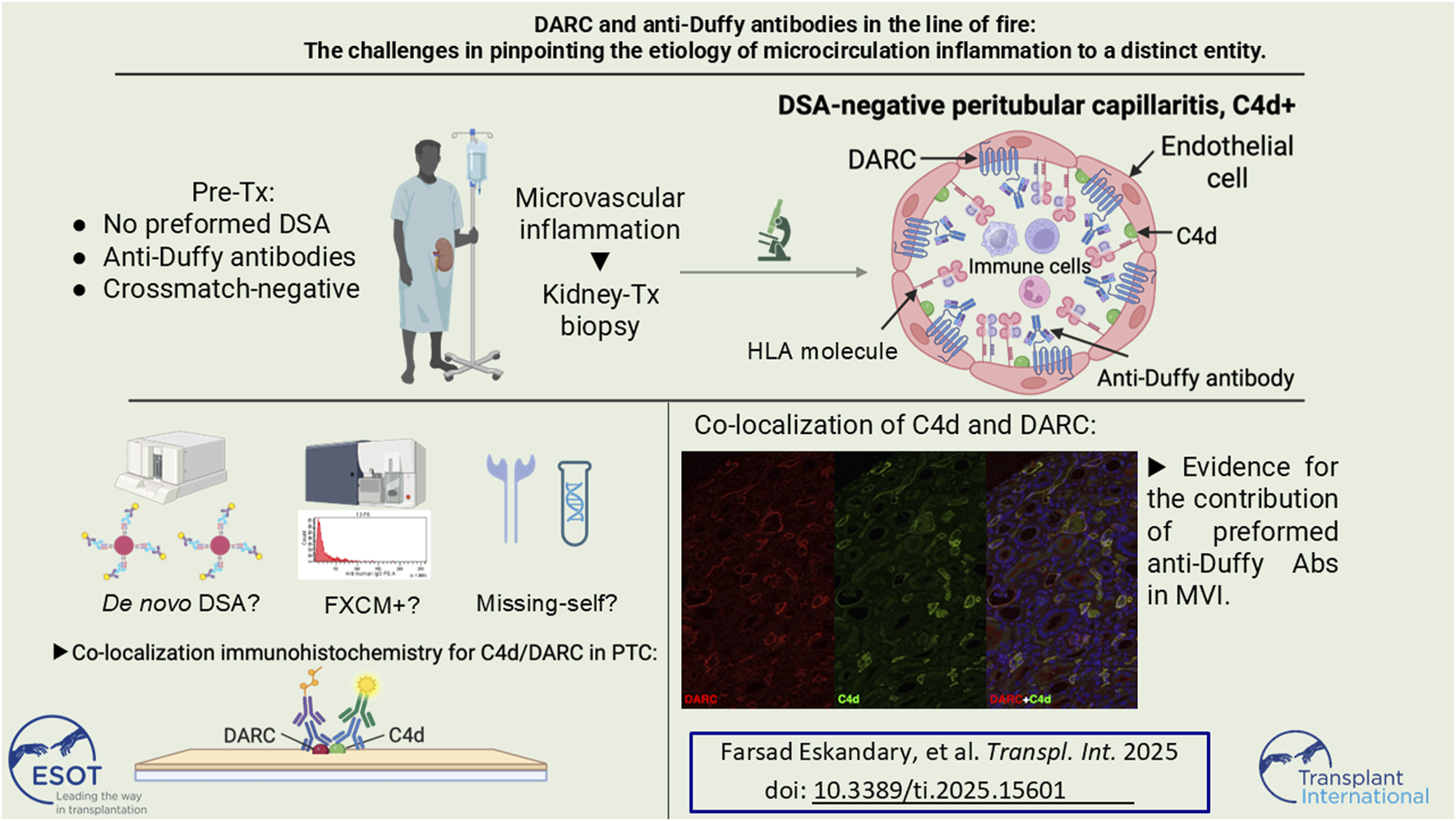

Antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR) due to non-HLA alloantibodies has gained substantial attention in transplantation research. One candidate for such non-HLA reactivity is the Duffy blood group carrier molecule DARC, which is not only expressed on erythrocytes, but also on kidney microvascular endothelial cells and is postulated as a potential transplantation-relevant alloantigen. However, in vivo observation of anti-Duffy antibodies as trigger of microvascular inflammation (MVI) is lacking. Here we propose a direct relationship between preformed anti-Duffy (anti-Fya) antibodies, complement deposition (C4d) in peritubular capillaries (PTC), and MVI. Double immunofluorescence for DARC and C4d in sequential biopsies revealed a striking overlap of DARC expression and C4d staining that was completely restricted to the peritubular capillaries. Remarkably, MVI was confined to PTC with complete absence of glomerulitis and lack of preformed anti-HLA DSA. Retrospective analysis revealed a self-limiting posttransplant flare of a low-level anti-DQ8 DSA after blood transfusions and a high missing-self KIR ligand constellation. Concomitant occurrence of non-HLA and anti-HLA reactivities next to missing-self constellations substantially complicates the assessment of individual contributions for the development and propagation of MVI. Due to the strictly confined distribution of DARC to PTC our report provides in vivo evidence that anti-Fya alloantibodies may associate with MVI.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR) constitutes one of the major causes for late allograft loss after kidney transplantation [1, 2]. While the majority of ABMR cases is positive for anti-HLA donor-specific antibodies (DSA), some evidence also supports a role of non-HLA antigens as primary targets of alloantibodies [3]. Clinicians usually only search for such antibodies, when serologic evidence of anti-HLA DSA is lacking despite typical ABMR lesions in biopsies. Detection of non-HLA alloantibodies is challenging, as only a limited number of validated assays are commercially available. Furthermore, the most comprehensive Luminex-based non-HLA antibody assays failed to correlate in a substantial proportion, hindering the development of recommendations for their routine testing [4, 5]. The occurrence of ABMR lesions in anti-HLA DSA-negative patients has recently been introduced as a diagnostic category of the Banff classification termed “microvascular inflammation (MVI) DSA and C4d negative,” because some studies observed its detrimental impact on graft survival [6, 7]. In this context it is of interest that particular donor/recipient HLA class I mismatches may trigger NK cells via KIR’s through the ‘missing-self’ pathway, leading to MVI through antibody-independent mechanisms [8].

The glycoprotein “Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines” (DARC) encoded on chromosome 1 constitutes a transfusion-relevant blood group system, belongs to the family of seven-transmembrane proteins, and exhibits clinically relevant Duffy blood group antigens (Fya or Fyb, depending on genotype) [9]. Its expression in the kidney vasculature is almost exclusively limited to the endothelium of peritubular capillaries (PTC) and postcapillary venules [10]. DARC was shown to be upregulated during kidney transplant rejection processes and its expression correlated with the extent of interstitial fibrosis in biopsies showing ABMR [11, 12]. Also, in gene expression profiling of kidney transplant biopsies [Molecular Microscope Diagnostic System (MMDx™) and NanoString®], DARC appeared as one of the most prominent ABMR-associated transcripts [13, 14]. Apart from a possible role in rejection, DARC has also been proposed as a transplantation-relevant antigen due to the fact that Duffy alloantibodies can form after sensitizing events [15, 16]. DARC genotype-mismatch constellations in kidney transplantation showed varying associations with respect to the occurrence of rejection, enhanced fibrosis and reduced graft survival. However, in vivo proof of such antibodies to directly contribute to ABMR are lacking [17–19].

Here we present the case of a patient with preformed anti-Fya, who received a kidney transplant from a Fy(a+b-) donor and subsequently developed early C4d+ microvascular inflammation (MVI), at that time without the evidence of any anti-HLA DSA in serum. We retrospectively performed double immunofluorescence for C4d and DARC in biopsies to assess a potential co-localization of the antigens and their spatial relation to histologic signs of rejection. In this paper we describe the process of corroborating our findings, thorough retrospective workup of patient sera revealed the complexity of the observed MVI with respect to a causative role of anti-Fya antibodies.

Methods

Biopsies

All biopsies were graded according to the 2022 update of the Banff classification. For C4d immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence staining we used a polyclonal anti-C4d antibody (BI-RC4D; Biomedica, Vienna, Austria) and for DARC immunofluorescence we used a mouse monoclonal anti-human DARC-Fy6 antibody (a generous gift from the laboratory of Prof. Yves Colin, INSERM). The detailed protocol of our DARC and C4d double-immunofluorescence is provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Anti-Duffy Antibody Titration

Anti-Fya titration was performed using indirect antihuman globulin technique in gel matrix (MicroTyping system, Bio-Rad, Vienna, Austria).

Anti-HLA Antibody Assessment, HLA and KIR Typing

HLA antibody detection was performed at our ISO-certified HLA laboratory, using LABscreen single-antigen flow-bead assays (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA). Details with respect to donor/recipient high-resolution HLA typing, anti-HLA reactivities, HLA eplet mismatch, KIR typing and missing-self and are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

FXCM Crossmatch

A detailed technical description of the FCXM is provided in the Supplementary Appendix. In brief, mononuclear cells from donor spleen were extracted using LymphoprepTM density medium. After pronase digestion to deplete unspecific binding, sera were incubated with B and T lymphocytes and incubated with corresponding antibody-mixes. Controls were performed to account for unspecific binding, enzymatic digestion and equal HLA distribution on cell surfaces. Positivity threshold for FXCM results was >6000 MFI above the mean of negative control values.

Results

In 2017, a 45-year-old male on peritoneal dialysis with a history of opioid abuse and hepatitis C-associated membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (nucleic acid test-negative since 2015), received his first ABO-compatible deceased donor kidney transplant from a 51-year-old male. HLA mismatch was 0/1/1/1/1/1 (A/B/C/DR/DQ/DP), pretransplant CDCXM was negative and single antigen bead (SAB) testing revealed no preformed anti-HLA DSA (latest vPRA for HLA class I and II: 0%, highest historic vPRA: 7%). Anti-IL2 receptor antibody basiliximab was administered on days 0 (d0) and d4 (20 mg each) and maintenance immunosuppression consisted of standard triple immunosuppression with tacrolimus, mycophenolate-mofetil and steroids.

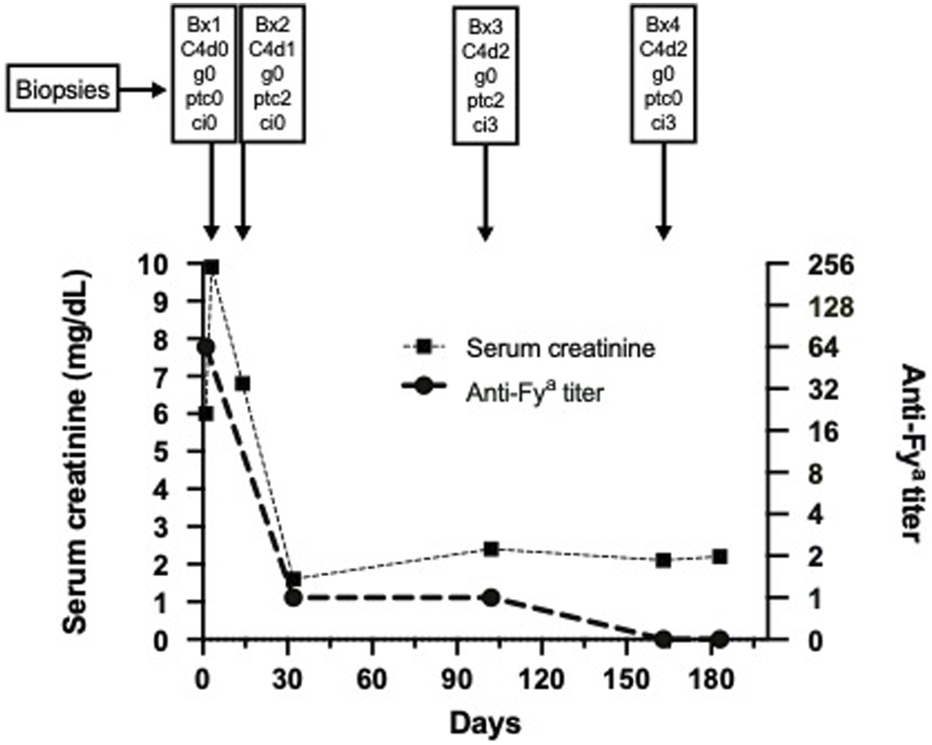

Upon transplant offer, previously identified donor-specific anti-Fya IgG was detectable, with an anti-Fya antibody titer of 64 (donor and recipient DARC genotypes FY*A and FY*B, respectively). Anti-Fya immunization was most likely due to prior RBC transfusion because of an episode of idiopathic autoimmune hemolytic anemia in 2005. We decided against any desensitization scheme, but to liberally perform transplant biopsies in case of graft dysfunction. The post-transplantation course was complicated by delayed graft function (DGF) most likely due to peri-renal hematomas that impaired global allograft perfusion, requiring two surgical revisions within the first week, and hemodialysis on day four (d4). A concomitant allograft biopsy on d4 contained very little cortical tissue, but showed severe tubular injury with tubular necrosis without signs of rejection and was C4d-negative. A second biopsy on d14 showed resolving tubular injury without TCMR, but now diffuse peritubular capillaritis (ptc2) and minimal linear C4d in PTC (C4d1), suggestive of antibody-mediated injury. Anti-HLA DSA were not detected. Meanwhile, the anti-Fya antibody titer had decreased to just above the detection level. Due to this early complicated course, with serum creatinine values stabilizing at around 1.5 mg/dL and absence of albuminuria/proteinuria, no anti-rejection treatment was initiated. At month three serum creatinine increased to >2 mg/dL, which prompted us to administer a steroid bolus before performing a biopsy, that still showed diffuse ptc2, but this time also a strong linear C4d-positivity in PTC (C4d2). There was still no sign of TCMR, but surprisingly we found mild diffuse interstitial fibrosis (ci3, affecting 70% of cortex) without chronic tubular damage (ct0); in electron microscopy no doubling of PTC basement membranes was found (MLPTC0). Repeated testing confirmed the absence of anti-HLA DSA, an anti-Fya titer decreasing below the detection limit and serum creatinine remaining at around 2 mg/dL. We decided to not further intensify immunosuppression, as our patient appeared prone to infectious complications (paralytic ileus with sepsis 4 months and pneumonia with subsequent right-sided surgical decortication for empyema 7 months post transplantation). Tacrolimus trough-level goal was set between 4 and 8 ng/mL and was mostly achieved with singular outliers in the upper and lower ranges (Median tacrolimus level day 14 until month ten after transplantation: 5.9 ng/mL, IQR: 4.3–6.4 ng/mL). Mycophenolate-mofetil was switched to azathioprine at month two because of gastrointestinal side effects. Torque-Teno-Virus PCR was assessed as a measure for global immunosuppression and was in the range of 104 and 108 copies, indicating no excessive immunosuppressive effect.

At month five BK-viremia (max: 6.5 × 103 copies/mL) together with decoy cells in urine (max: 90% of epithelial cells) were noted and a fourth biopsy at month seven showed BKPyVAN with positive multifocal SV40-positive nuclei, surprisingly together with moderate C4d in PTC (C4d2). Mild chronic interstitial fibrosis was now even more diffuse (ci3, affecting 100% of cortex), tubulitis and interstitial inflammation (i1, t3, ti1) were present, but in the absence of clinical deterioration were interpreted as signs of resolving BKPyVAN. Immunosuppression had already been reduced and BK-viremia together with decoy cell amount resolved gradually. Graft function stabilized at a creatinine of 1.6 mg/dL without any proteinuria. Since 2019 our patient was followed up at a remote center, where lung cancer was diagnosed and he died in mid-2020 with a functioning allograft. The serum creatinine and anti-Fya antibody titer trajectories in the context of biopsy results are provided in Figure 1. Detailed biopsy findings and representative histologic images are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figures S1A–D.

FIGURE 1

Serum creatinine course and anti-Fya antibody titer over time together with corresponding biopsy results. Abbreviations: Bx, biopsy; g, glomerulitis; ptc, peritubular capillaritis; ci, chronic interstitial fibrosis; C4d, complement split product C4d.

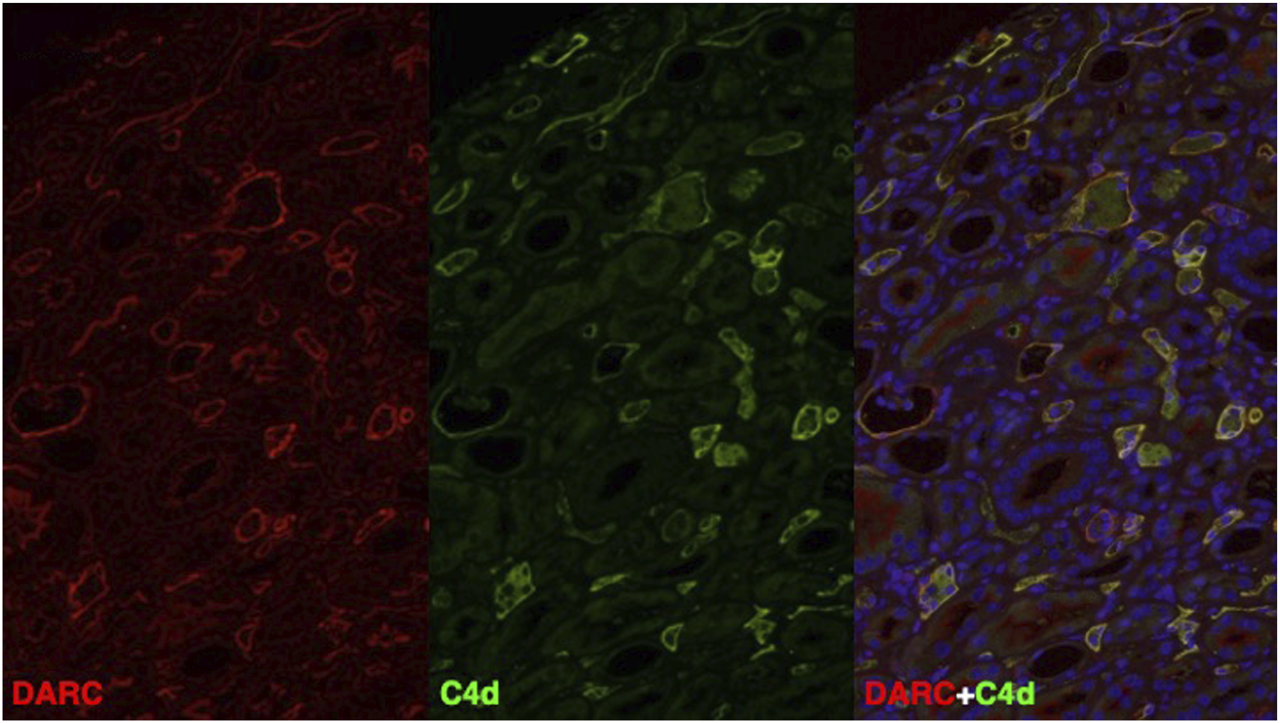

Due to the continuous presence of MVI in PTC without anti-HLA DSA but with endothelial C4d deposition, a causal relationship with the donor-specific anti-Fya antibodies was suspected and we therefore retrospectively performed double immunofluorescence for C4d and DARC in all four biopsies. In all three biopsies with linear C4d deposition, C4d was only positive in PTC, but not in glomeruli. DARC staining was only positive in PTC and absent in glomeruli. Most strikingly, and as illustrated in Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S2, C4d and DARC showed a high degree of co-localization and similar staining intensity. This finding was considered highly suggestive of anti-DARC antibody-mediated C4d deposition in PTC.

FIGURE 2

DARC (red) and C4d (green) and DAPI (blue) immunofluorescence staining in a representative biopsy specimen (Bx No. 3) fulfilling the Banff 2022 criteria for antibody-mediated rejection. On the right, double immunofluorescence is shown, where all areas with co-localization staining of DARC and C4d show high overlap (yellow = double positive) with respect to the positive area in PTC. Abbreviations: C4d, complement split product C4d; DARC, Duffy antigen-receptor of chemokines.

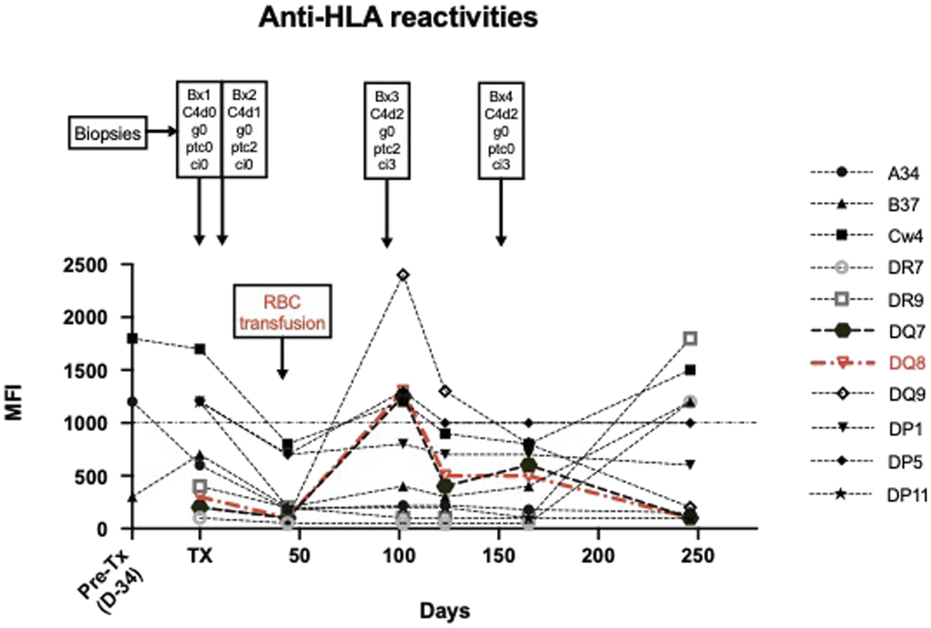

In order to corroborate our suspicion of ABMR mediated through anti-DARC antibodies, we performed detailed retrospective analysis of sera and NK cell genetics to rule out other contributors for MVI. As depicted in Figure 3 and shown in Supplementary Tables S2, S3 we were able to identify a transient and short-lived low-level anti-DQ8 DSA (MFI 1,300) around month three. Next, we retrospectively performed serial B and T FXCM using frozen cells from the kidney donor in order to pinpoint SAB results to biological relevance. We found that the transient DQ8 reactivity also coincided with a positive B cell FXCM (Supplementary Figures S3A–G), all other FXCM remained negative. Clinical workup showed that the occurrence of anti-DQ reactivities was closely related to the administration of RBC’s (Figure 3) and disappeared spontaneously without any treatment. A thorough description and interpretation of our SAB findings can be found in the Supplementary Appendix.

FIGURE 3

Illustrates anti-HLA reactivities over time in the context of biopsy results and the administration of RBC transfusions. Donor-specific antibody reactivities are shown in Red. A detailed discussion on the interpretation of SAB findings can be found in the Supplementary Appendix.

The option of MVI potentially being triggered by missing self, prompted us to perform donor/recipient KIR typing that revealed a high missing-self constellation for two established ligands (A11/KIR3DL2 and C2/KIR2DL1, Supplementary Table S4).

In follow-up biopsies MVI and C4d remained constantly high and interstitial fibrosis progressed without overt functional graft deterioration, again with no sign of glomerulitis or chronic glomerular lesions.

Discussion

This is the first description of a potential in vivo relationship between the non-HLA antigen DARC, preformed anti-Duffy antibodies and histologic ABMR features in a kidney transplant. Immunofluorescent double-labelling revealing co-localization of DARC and C4d further supported anti-Duffy antibodies as potential cause of ABMR.

The combination of a recipient with preformed anti-Fya antibodies receiving an Fya-positive donor kidney in the absence of anti-HLA alloreactivity is a rare event. We found only one report of a patient with preformed anti-Duffy antibodies who developed CDCXM-negative mixed rejection with crescentic GN, rendering the interpretation of Duffy-specific ABMR without SAB testing almost impossible as also upregulation of DARC during crescentic GN has already been demonstrated [20, 21].

Our findings are consistent with DARC acting as a non-HLA antigen potentially leading to clinically relevant rejection in kidney allografts. Our observation that interstitial fibrosis increased rapidly over time does confirm our previous findings showing that DARC expression on the transcriptome level, but also in IHC correlated well with fibrosis [11]. However, this study included patients with late ABMR, where DARC expression was investigated as a surrogate marker for ABMR and not as primary alloantibody target. DARC expression may lead to increases in cytokine levels within capillaries and thereby attract immune cells contributing to inflammation and potentially enhance subsequent fibrosis [22, 23]. One may argue that in this specific situation, preventive measures such as plasmapheresis or immunoadsorption could have been applied to prevent rejection due to anti-Fya antibodies, whereas declining this organ in order to wait for a Fya-negative donor (approximately 32% of Caucasians) would not have been an ideal option [24]. With respect to the literature we found no strong recommendation regarding desensitization, but our report indicates that it may be warranted in such a case [15].

The co-localization of DARC and C4d within PTC suggests that DARC might be a relevant non-HLA antigen, with anti-Fya antibodies being capable of mediating ABMR. However, a caveat to our hypothesis is the fact that patients with anti-Fya antibodies, generally sensitized by blood transfusions, have a chance to also be sensitized against HLA. In our case in-depth analysis indeed revealed a low-level anti-DQ8 DSA after administration of RBC transfusions early posttransplant, which was confirmed by corresponding B cell FXCM reactivity. However, subsequently all anti-DQ reactivities faded without treatment, which is not supporting the occurrence of a memory response or de novo DSA formation. The appearance of transfusion-specific anti-HLA class II antibodies that also may act as DSA has been demonstrated earlier, but it has not been documented whether these reactions cause long-term or only short-term memory as it happened in our case [25]. In addition, this also did not lead to clinical deterioration, new onset of proteinuria or aggravation of MVI, even though we retrospectively demonstrated a high degree of “missing-self” constellation. It is interesting that despite having two degrees of missing-self, this failed to manifest glomerular MVI, making DARC expression the primary reason for MVI in PTC. A possible explanation for a milder course of ABMR due to anti-Duffy antibodies might be the fact, that DARC is - if at all - only very weakly expressed in glomeruli, which would explain the lack of proteinuria despite early renal deterioration in our patient [12]. This is also supported by the absence of glomerulitis, and C4d deposition being exclusively restricted to the PTC compartment.

This report illustrates the challenges associated with establishing the diagnosis of non-HLA-mediated ABMR on the basis of an actual clinical case. Despite having made use of our full current diagnostic armamentarium - with the exception of a lack of molecular biopsy diagnostics due to insufficient remaining material - and in order to perform a deep dive into the different potential immunologic processes that might have contributed to MVI in our patient, it seems almost impossible to provide definite evidence for a causal relationship between a non-HLA DSA and MVI in our representative case. Of note, the different potential triggers of MVI are not mutually exclusive, and other conditioning factors such as DGF and ischemia might also have played a role in this specific scenario.

Nevertheless, our findings strengthen a potential association of preformed anti-Fya antibodies with MVI, but our report also highlights the caution that is warranted to exclude the remaining causes of MVI, rendering it a highly complex task to prove causality [26].

Statements

Data availability statement

Original datasets are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because Patient has deceased before project. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The human samples used in this study were acquired from a by- product of routine care or industry. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article because Patient has deceased before research project was started.

Author contributions

FE, GK, and HR designed the study and wrote the manuscript draft. MS, HS, and DK carried out experiments. GF, IF, and SW helped with interpretation of the data and experiments. RO, RR-S, AH, JK, NK, SS, KD, LH, and GB worked on the manuscript draft and helped with interpretation of the results. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by a research grant from the Christine-Vranitzky-Stiftung zur Förderung der Organtransplantation (Project number: P4/5/8200-Grant_19) granted to FE.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prof. Yves Colin from INSERM for supplying the Anti-Fy6 antibody.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ti.2025.15601/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

ABMR, antibody-mediated rejection; BKPyVAN, polyomavirus-associated nephropathy; CDCXM, cytotoxicity-dependent crossmatch; DARC, Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines; DGF, delayed graft function; DSA, donor-specific antibody; FXCM, flow cytometric crossmatch; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; ISBT, international society for blood transfusion; KIR, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor; MVI, microvascular inflammation; MLPTC, multilayering of peritubular capillary basement membranes; MMDx™, molecular microscope diagnostic system; PTC, peritubular capillaries; RBC, red blood cell transfusion; SAB, single antigen bead; SOT, solid organ transplantation; TCMR, T cell-mediated rejection; vPRA, virtual panel-reactive antibodies.

References

1.

MayrdorferMLiefeldtLWuKRudolphBZhangQFriedersdorffFet alExploring the Complexity of Death-Censored Kidney Allograft Failure. J Am Soc Nephrol (2021) 32(6):1513–26. 10.1681/ASN.2020081215

2.

SellaresJde FreitasDGMengelMReeveJEineckeGSisBet alUnderstanding the Causes of Kidney Transplant Failure: The Dominant Role of Antibody-Mediated Rejection and Nonadherence. Am Journal Transplantation (2012) 12:388–99. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03840.x

3.

Reindl-SchwaighoferRHeinzelAKainzAvan SettenJJelencsicsKHuKet alContribution of non-HLA Incompatibility Between Donor and Recipient to Kidney Allograft Survival: Genome-Wide Analysis in a Prospective Cohort. Lancet (2019) 393(10174):910–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32473-5

4.

TamburARBestardOCampbellPChongASBarrioMCFordMLet alSensitization in Transplantation: Assessment of Risk 2022 Working Group Meeting Report. Am Journal Transplantation (2023) 23(1):133–49. 10.1016/j.ajt.2022.11.009

5.

ObriscaBLecaNChou-WuESibuleskyLBakthavatsalamRKlingCEet alHeterogeneity of Non-HLA Antibody Prevalence in Kidney Antibody-Mediated Rejection with the Commercial Luminex Assays. Transplantation (2025) 109(8):e409–e421. 10.1097/TP.0000000000005363

6.

SenevACoemansMLerutEVan SandtVDaniëlsLKuypersDet alHistological Picture of Antibody-Mediated Rejection Without Donor-Specific Anti-HLA Antibodies: Clinical Presentation and Implications for Outcome. Am Journal Transplantation (2019) 19(3):763–80. 10.1111/ajt.15074

7.

NaesensMRoufosseCHaasMLefaucheurCMannonRBAdamBAet alThe Banff 2022 Kidney Meeting Report: Reappraisal of Microvascular Inflammation and the Role of Biopsy-Based Transcript Diagnostics. Am Journal Transplantation (2024) 24(3):338–49. 10.1016/j.ajt.2023.10.016

8.

KoenigAChenCCMarcaisABarbaTMathiasVSicardAet alMissing Self Triggers NK Cell-Mediated Chronic Vascular Rejection of Solid Organ Transplants. Nat Commun (2019) 10(1):5350. 10.1038/s41467-019-13113-5

9.

HorukRChitnisCEDarbonneWCColbyTJRybickiAHadleyTJet alA Receptor for the Malarial Parasite Plasmodium Vivax: The Erythrocyte Chemokine Receptor. Science (1993) 261(5125):1182–4. 10.1126/science.7689250

10.

HadleyTJLuZHWasniowskaKMartinAWPeiperSCHesselgesserJet alPostcapillary Venule Endothelial Cells in Kidney Express a Multispecific Chemokine Receptor that Is Structurally and Functionally Identical to the Erythroid Isoform, Which Is the Duffy Blood Group Antigen. J Clin Invest (1994) 94(3):985–91. 10.1172/JCI117465

11.

KlagerJEskandaryFBohmigGAKozakowskiNKainzAColin AronoviczYet alRenal Allograft DARCness in Subclinical Acute and Chronic Active ABMR. Transpl International (2021) 34(8):1494–505. 10.1111/tri.13904

12.

SegererSBohmigGAExnerMColinYCartronJPKerjaschkiDet alWhen Renal Allografts Turn DARC. Transplantation (2003) 75(7):1030–4. 10.1097/01.TP.0000054679.91112.6F

13.

AdamBASmithRNRosalesIAMatsunamiMAfzaliBOuraTet alChronic Antibody-Mediated Rejection in Nonhuman Primate Renal Allografts: Validation of Human Histological and Molecular Phenotypes. Am Journal Transplantation (2017) 17(11):2841–50. 10.1111/ajt.14327

14.

VennerJMHidalgoLGFamulskiKSChangJHalloranPF. The Molecular Landscape of Antibody-Mediated Kidney Transplant Rejection: Evidence for NK Involvement Through CD16a Fc Receptors. Am Journal Transplantation (2015) 15(5):1336–48. 10.1111/ajt.13115

15.

HoltSGKotagiriPHoganCHughesPMastersonR. The Potential Role of Antibodies Against Minor Blood Group Antigens in Renal Transplantation. Transpl International (2020) 33(8):841–8. 10.1111/tri.13685

16.

HaririDBordasJElkinsMGallayBSpektorZHod-DvoraiR. The Role of the Duffy Blood Group Antigens in Renal Transplantation and Rejection. A Mini Review. Transpl International (2023) 36:11725. 10.3389/ti.2023.11725

17.

AkalinENeylanJF. The Influence of Duffy Blood Group on Renal Allograft Outcome in African Americans. Transplantation (2003) 75(9):1496–500. 10.1097/01.TP.0000061228.38243.26

18.

LerutEVan DammeBNoizat-PirenneFEmondsMPRougerPVanrenterghemYet alDuffy and Kidd Blood Group Antigens: Minor Histocompatibility Antigens Involved in Renal Allograft Rejection?Transfusion (2007) 47(1):28–40. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01060.x

19.

MangeKCPrakELKamounMDuYGoodmanNDanoffTet alDuffy Antigen Receptor and Genetic Susceptibility of African Americans to Acute Rejection and Delayed Function. Kidney International (2004) 66(3):1187–92. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00871.x

20.

WatorekEBoratynskaMHalonAKlingerM. Anti-Fya Antibodies as the Cause of an Unfortunate Post-Transplant Course in Renal Transplant Recipient. Ann Transpl (2008) 13(1):48–52.

21.

SegererSCuiYEitnerFGoodpasterTHudkinsKLMackMet alExpression of Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors During Human Renal Transplant Rejection. Am J Kidney Dis (2001) 37(3):518–31. 10.1016/s0272-6386(01)80009-3

22.

LiuXHHadleyTJXuLPeiperSCRayPE. Up-Regulation of Duffy Antigen Receptor Expression in Children with Renal Disease. Kidney International (1999) 55(4):1491–500. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00385.x

23.

PruensterMMuddeLBombosiPDimitrovaSZsakMMiddletonJet alThe Duffy Antigen Receptor for Chemokines Transports Chemokines and Supports Their Promigratory Activity. Nat Immunol (2009) 10(1):101–8. 10.1038/ni.1675

24.

MenyGM. The Duffy Blood Group System: A Review. Immunohematology (2010) 26(2):51–6. 10.21307/immunohematology-2019-202

25.

HassanSReganFBrownCHarmerAAndersonNBeckwithHet alShared Alloimmune Responses Against Blood and Transplant Donors Result in Adverse Clinical Outcomes Following Blood Transfusion Post-Renal Transplantation. Am Journal Transplantation (2019) 19(6):1720–9. 10.1111/ajt.15233

26.

BohmigGALoupyASablikMNaesensM. Microvascular Inflammation in Kidney Allografts: New Directions for Patient Management. Am Journal Transplantation (2025) 25(7):1410–6. 10.1016/j.ajt.2025.03.031

Summary

Keywords

antibody-mediated rejection (AMR), humoral rejection, DSA, donor specific antibodies, Duffy blood group

Citation

Eskandary F, Körmöczi GF, Schönbacher M, Fischer G, Faé I, Wenda S, Koren D, Oberbauer R, Reindl-Schwaighofer R, Heinzel A, Kläger J, Kozakowski N, Segerer S, Doberer K, Hidalgo LG, Schachner H, Böhmig GA and Regele H (2026) DARC and Anti-Duffy Antibodies in the Line of Fire: The Challenges in Pinpointing the Etiology of Microcirculation Inflammation to a Distinct Entity. Transpl. Int. 38:15601. doi: 10.3389/ti.2025.15601

Received

18 September 2025

Revised

05 November 2025

Accepted

16 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

38 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Eskandary, Körmöczi, Schönbacher, Fischer, Faé, Wenda, Koren, Oberbauer, Reindl-Schwaighofer, Heinzel, Kläger, Kozakowski, Segerer, Doberer, Hidalgo, Schachner, Böhmig and Regele.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Farsad Eskandary, farsad.eskandary@meduniwien.ac.at

ORCID: Farsad Eskandary, orcid.org/0000-0002-8971-6149; Günther F. Körmöczi, orcid.org/0000-0002-5490-9987; Johannes Kläger, orcid.org/0000-0001-5761-0713; Nicolas Kozakowski, orcid.org/0000-0001-9180-620X; Stephan Segerer, orcid.org/0000-0002-1936-9719; Konstantin Doberer, orcid.org/0000-0002-8036-7042; Georg A. Böhmig, orcid.org/0000-0002-7600-912X; Heinz Regele, orcid.org/0000-0003-2929-6135

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.