Abstract

Transplantation improves survival and quality of life, but rejection remains a major threat to allograft longevity. Current surveillance relies heavily on protocols with clinically indicated biopsies, which are invasive, carry procedure-related risks, and have variable sensitivity due to sampling and interpretation limitations. Percent donor-derived cell-free DNA (%dd-cfDNA) has emerged as a noninvasive blood-based biomarker for allograft injury and a potential rule-out test for rejection. Centralized commercial assays are increasingly used in clinical practice; however, published studies report heterogeneous performance and reveal important blind spots and confounders. This review synthesizes the evidence for %dd-cfDNA in thoracic transplantation, delineates its limitations, and outlines emerging cfDNA methodologies that may reduce reliance on invasive biopsies and enable more individualized monitoring strategies.

Introduction

Acute rejection (AR) remains a critical vulnerability in thoracic transplantation. Clinicians rely on traditional biopsies of the allograft to detect AR and two classic phenotypes: acute cellular rejection (ACR) and antibody-mediated rejection (AMR). The traditional one-size-fits-all monitoring protocol performs repeated surveillance biopsies to detect and treat early forms of AR before irreversible allograft injury, chronic rejection, and allograft failure develop. Testing often necessitates intricate coordination among various specialties, procedural services, and advanced care planners [1, 2]. This complex model places a substantial burden on healthcare systems and patients alike, ultimately imposing significant socioeconomic across a wide spectrum of care [1, 3, 4]. Moreover, the low sensitivity and high inter-rater variability of biopsy further compromise transplant outcomes [5, 6].

In light of these challenges, donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) has emerged as a highly sensitive and non-invasive alternative to biopsy. Cell-free nucleic acids are circulating DNA and RNA fragments (cfDNA and cfRNA, respectively) that are released from nuclear, mitochondrial, or microbial genomes into the peripheral bloodstream at the time of cell injury and/or death. In transplant patients, both the recipient and donor contribute to the circulating cell-free nucleic acid pool (rd-cfDNA and dd-cfDNA, respectively).

Cohort studies among transplant patients demonstrate excellent diagnostic performance of dd-cfDNA, with high negative predictive values when used to screen for acute rejection, primary graft dysfunction, and chronic rejection in clinically stable patients [7]. With the availability of commercial testing, %dd-cfDNA has been increasingly adopted in routine clinical care at US and European Centers, particularly large academic institutions [8–10]. Clinical experiences, however, have been mixed: some centers report consistent performance aligning with early cohort findings, while others exhibit less favorable results alongside challenges with interpretation [7, 11, 12]. To optimize integration into routine clinical care, it is paramount to address the blind spots of %dd-cfDNA and move beyond the one-size-fits-all monitoring paradigm in thoracic transplant populations.

This review aims to highlight the strengths, blind spots, and novel approaches using cfDNA to address these dd-cfDNA gaps.

Historical Basis: The Advent of Cell-free DNA Technology

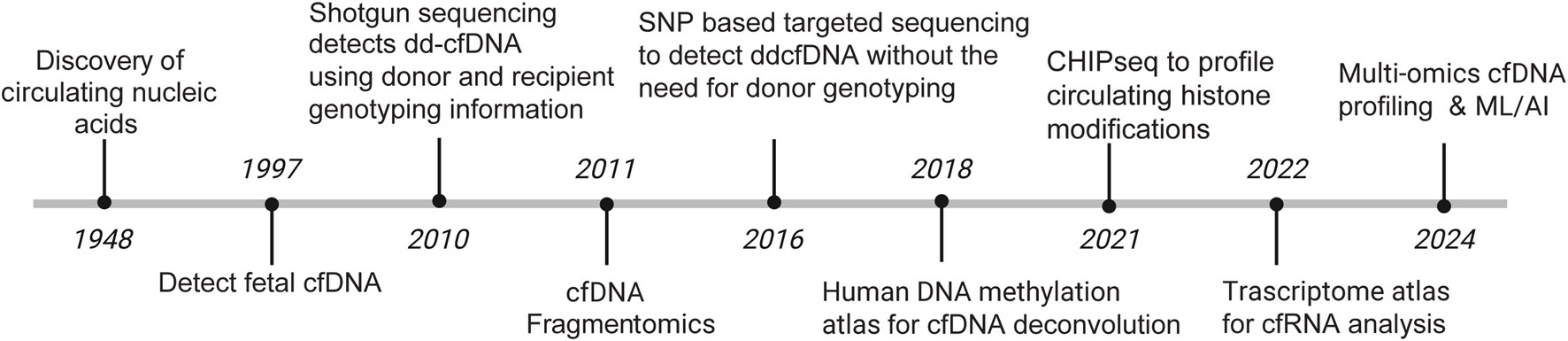

Transplantation restores organ function and creates a donor–recipient genomic admixture wherein measurement of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) provides a noninvasive window into allograft health. Half a century after the discovery of cfDNA in human plasma, Denis Lo first reported on the presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma in 1997 [13]. Despite these initial findings, cfDNA adoption in transplantation was initially slow. In 2010, Dr. Stephen Quake published a SNP-based approach that leveraged the unique transplant genomic admixture [14]. This 1st generation assay genotyped transplant donors and recipients to identify informative donor-recipient single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Post-transplant plasma was then subjected to cfDNA isolation and whole genome sequencing and reads were analyzed using SNPs to assign donor and recipient cfDNA fragments. Percent dd-cfDNA (%dd-cfDNA) was then computed as the donor-to-total (donor plus recipient) cfDNA percentage, which has become the standard reported value in transplant populations. Since then, commercial %dd-cfDNA tests are increasingly available for routine clinical care. These SNP-based assays used a targeted approach and imputed donor and recipient SNPs without the need for genotype data. Figure 1 summarizes the modern evolution of cfDNA technologies.

FIGURE 1

Evolution of cfDNA technologies.

Novel cfDNA approaches (3rd generation) have emerged in the last decade and while they do not fix the listed weaknesses, they offer mechanisms that utilize epigenetic fingerprints on cfDNA to better characterize tissue-specific contributions and highlight molecular mechanisms of action [15]. In theory, these approaches could unveil known and unknown pathobiological information of AMR and ACR using a single vial of blood. We summarize these different epigenetic technologies at the end of this review.

Current Knowledge

Cell-Free DNA to Detect Acute Rejection

Table 1 summarizes seminal studies on the use of cfDNA in thoracic transplant, highlighting the wide range of %dd-cfDNA cutoffs used in initial validation studies and the ongoing work that must be done before %dd-cfDNA is widely adopted. The Stanford Genome Transplant Dynamics (GTD) team launched the initial transformative studies in both heart and lung transplants. The NHLBI-funded Genomic Research Alliance for Transplantation (GRAfT) consortium has since built on these initial studies.

TABLE 1

| Transplant type | Author | Study design | Sample size (n) | Biomarker threshold | Data Collection methodology | AUROC | Specificity (%) | Sensitivity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart transplantation | De Vlaminck et al. [16] | Single-center prospective cohort study | 65 | Dd-cfDNA ≥0.25% to detect acute cellular rejection (ISHLT ≥2R/3A) or AMR | SNP-based shotgun sequencing | 0.83 | 58 | 93 | - | - |

| Khush et al. [17] | Multicenter prospective cohort study + single center cohort study | 773 | ddcfDNA ≥0.2% to detect acute rejection | Allosure | 0.64 | 80 | 44 | 8.9 | 97.1 | |

| Agbor-Enoh et al. [18] | Multicenter prospective cohort study | 171 | Day 28 ddcfDNA ≥0.25% to detect biopsy-positive acute rejection | SNP-based shotgun sequencing | 0.92 | 81 | 85 | 19.6 | 99.2 | |

| Knuttgen et al. [19] | Single-center prospective cohort study | 87 | ddcfDNA ≥0.35% to detect severe rejection (ISHLT 1R/2R) | Therasure transplant monitor | 0.81 | 83 | 76 | 31 | 97 | |

| Kim et al. [20] | Observational single-center cohort study | 223 | ddcfDNA ≥0.15% to detect acute rejection | Prospera | 0.86 | 76.9 | 78.5 | 25.1 | 97.3 | |

| Absolute quantity ddcfDNA ≥13 cp/mL to detect acute rejection | 0.88 | 82.5 | 84 | 32.2 | 98.1 | |||||

| Bohmer et al. [21] | Multicenter observational prospective cohort study | 94 (24 children/70 adults) | Absolute quantity ddcfDNA ≥25 cp/mL to detect biopsy-confirmed rejection | SNP-based shotgun sequencing approach | 0.87 | 80.7 | 94.1 | 8.6 | 99.9 | |

| ddcfDNA ≥0.09% to detect biopsy-confirmed rejection | 0.75 | 49.3 | 88.2 | 3.1 | 99.6 | |||||

| Lung transplantation | De Vlaminck et al. [22] | Single-center prospective cohort study | 51 | ddcfDNA ≥1.0% to detect moderate-to-severe acute rejection | SNP-based shotgun sequencing | 0.9 | 100 | 73 | - | - |

| Jang et al. [23] | Multicenter prospective cohort study | 148 | Day 45 ddcfDNA ≥0.5% to detect acute rejection | SNP-based shotgun sequencing | 0.89 | 65 | 95 | 51 | 96 | |

| Day 45 ddcfDNA ≥1.0% to detect acute rejection | - | 84 | 77 | 64 | 90 | |||||

| Keller et al. [24] | Multicenter retrospective cohort study | 175 | ddcfDNA ≥1.0% to detect acute lung allograft dysfunction | SNP-based shotgun sequencing | 0.79 | 70 | 76.2 | 66.7 | 79.2 | |

| Rosenheck et al. [25] | Single-center prospective cohort study | 104 | Day 45 ddcfDNA ≥1.0% to detect acute rejection | Prospera | 0.91 | 89.1 | 82.9 | 51.9 | 97.3 | |

| Day 45 ddcfDNA ≥1.0% to detect combined allograft injury (ACR + AMR + CLAD/NRAD + INFXN) | 0.76 | 59.9 | 83.9 | - | - | |||||

| Ju et al. [26] | Single-center retrospective cohort study | 188 | Prediction score based upon ddcfDNA and mNGS ≥0.2781 to detect rejection | Allodx (NGS ddcfDNA system based upon analysis of 6200 SNPs) | 0.986 | 94.7 | 98.2 | 88.7 | 99.2 |

Seminal Studies in the Validation of dd-cfDNA as a marker for thoracic organ rejection.

Lung Transplant

In 2015, using the 1st generation SNP-based assay to measure %dd-cfDNA, De Vlaminck et al. reported excellent diagnostic performance with a ≥1% dd-cfDNA threshold used as indicator of AR when compared to traditional metrics of AR detection [22]. Lower grade ACR and AMR (A1 and A2) were not included.

Building on this initial data, GRAfT replicated and validated the cfDNA detection methods established by the Stanford GTD, enhancing the reliability and clinical applicability of %dd-cfDNA in assessing AR, which now included AMR and lower grades of ACR [27]. This early work resulted in a seminal publication by Jang et al. who proposed two %dd-cfDNA rejection detection thresholds of 1% and 0.5% dd-cfDNA indicative of a high and low risk patients, respectively [23]. This work set the stage for further clinical testing and validation studies, many of which have proposed different diagnostic thresholds to maximize the sensitivity and specificity of dd-cfDNA [25, 28–31].

In 2022, Keller et al. from the GRAfT consortium reported %dd-cfDNA performance as part of routine clinical care using a home-based surveillance program and thresholds from Jang et al. %dd-cfDNA demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance for detection of acute lung allograft dysfunction (ALAD–defined in this study as a composite endpoint of either acute rejection or infection) and its use successfully avoided 80% of bronchoscopies, which aligned with the GRAfT and other cohort study experiences [24, 31].

However, in 2024, Sindu et al. used the same commercial testing platforms and %dd-cfDNA thresholds but observed unsatisfactory sensitivity for detecting ACR or respiratory infection [11]. These diverging experiences are potentially valid and highlight the need to better understand the performance of the test in different patient populations. Future studies should also address multiple reported confounders that limit the assay performance [32–34].

Comparing the fidelity of %dd-cfDNA to more established rejection markers, %dd-cfDNA has a significantly higher sensitivity to detect rejection compared to FEV1 changes, 95% vs. 60%, while offering a more detailed injury map than traditional inflammatory markers such as ESR/CRP [23, 35]. Future studies would benefit from comparing the distinguishing performance of dd-cfDNA compared to ESR/CRP as studied within kidney transplantation [36].

Heart Transplant

The Stanford GTD published initial proof of concept for use of %dd-cfDNA in heart populations and the first seminal studies in their single center cohort [16]. In 2019, Khush et al. studied 740 heart transplant patients across 26 centers, pairing them with events of biopsy-proven rejection [17]. Using a 0.2% dd-cfDNA threshold, they reported a 97% NPV for detecting AR. Their findings indicated that %dd-cfDNA detected AR across a broad heart transplant population, not just in lung transplants.

Following those seminal studies, Agbor-Enoh et al. ran a prospective cohort study of 171 subjects through the GRAfT cohort [18]. Notably, AR showed higher %dd-cfDNA compared to controls, with elevations detectable 0.5–3.2 months before histopathologic diagnosis of both ACR and AMR via endomyocardial biopsy. A 0.25% threshold yielded a 99% NPV and could have avoided 81% of endomyocardial biopsies over the study period. Since these initial studies, multiple additional cohorts have emerged to validate diagnostic testing thresholds in AR [19, 20, 37]. We summarize seminal studies in Table 1 and the differing diagnostic thresholds for detecting AR in these cohorts across both heart and lung transplantation.

While most heart transplantation societies do not recommend routine AR screening with troponin/BNP/ESR given their low sensitivity, further studies are needed to directly compare these easily available biomarkers with %dd-cfDNA [2]. When compared directly with endomyocardial biopsy and cardiac MRI, %dd-cfDNA shows sensitivity to detect AR as high as 88% which is higher than MRI alone (85% sensitivity) and EMBx (as low as 58% sensitivity depending on technique) [6, 12, 38]. In the GRAfT cohort, EMB was positive in less than 20% of instances with positive %dd-cfDNA. Of note, %dd-cfDNA was shown to notably not distinguish between patients with angiographic cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV) post-transplant and those without, highlighting a particular weakness given the high frequency of and mortality associated with CAV [39].

Like with lung transplantation, experiences have been mixed across centers with–highlighting the challenges that still remain with using %dd-cfDNA routinely in heart transplantation. Institutions have reported inconsistent sensitivities for AR across a range of % cutoffs, high rates of non-rejection causes of elevated dd-cfDNA, and even that patients with elevated dd-cfDNA and negative biopsies had worse outcomes, highlighting areas for future studies [19, 40, 41].

Cell-Free DNA for Risk Stratification

Studies involving the long-term risk stratification ability of cfDNA have primarily focused on lung transplant populations within the GRAfT consortium, with cfDNA demonstrating consistent predictive performance throughout the transplant journey. In the pre-transplant period, Balasubramanian et al. evaluated 186 lung transplant candidates and reported variable n-cfDNA levels that were two-fold higher than those for healthy controls and were correlated with a patient’s Lung Allocation Score as well as other markers of disease severity [42]. Patients with high levels pre-transplant had higher risks of primary graft dysfunction and death post-transplant. The risk was highest in patients with elevated neutrophil-derived n-cfDNA, suggesting a role for pre-transplant n-cfDNA monitoring for risk evaluation and assessment.

High Early Injury after Transplantation (HEIT) also demonstrates predictive value, particularly injury in the early post-transplant period. In 2016, Agbor-Enoh et al. analyzed a cohort of 108 patients and reported variable %dd-cfDNA in the early post-transplant period. Patients with elevated %dd-cfDNA levels (upper tertile) showed higher rates of AMR, CLAD, and death when compared to those in the lower two tertiles [43]. Alnababteh et al. published a follow up study of rd-cfDNA in 215 patients and found that patients in the upper tertile had lower lung function post-transplant and an increased risk of death and AR when compared to the lower two tertiles [44]. Along a similar vein, Keller et al. evaluated the prognostic role of extreme molecular injury (EMI - measured as %dd-cfDNA above 5%) and found that all episodes of EMI were associated with an increased risk of severe CLAD or death [45]. Put together, there appears to be a close interplay between the allograft and the host which sets the stage for subsequent allograft function, rejection, and other poor outcomes.

Beyond the early post-transplant period, %dd-cfDNA drawn at the diagnosis of multiple acute post-transplant complications has predictive utility. In patients with respiratory pathogens, Bazemore K et al. showed that patients with %dd-cfDNA levels of 1% or higher showed increased risk of CLAD and death [32]. Keller et al. reported that patients with values above 1% at diagnosis of ACR demonstrated increased risk of CLAD and death [46, 47]. %dd-cfDNA levels at the diagnosis of organizing pneumonia and other acute complications are also predictive of CLAD and early death [48].

Cell-Free DNA to Monitor Infection

Microbial cfDNA (mcfDNA) is found alongside human cfDNA in peripheral blood at lower concentrations and metagenomic sequencing of mcfDNA is an emerging tool that enables unbiased pathogen detection. Currently, there is a commercial clinical-grade mcfDNA sequencing test called the Karius Test that identifies over 1,250 clinically relevant bacteria, DNA viruses, fungi, and parasites non-invasively [49]. Studies have leveraged microbial cfDNA to detect new pathogens in transplant populations and assess a patient’s immunosuppression status [50, 51]. Although this approach has a limitation in identifying colonization versus active infection, it has the potential to detect unculturable and emerging microbes as well as help to distinguish AR from active infection–a known limitation of %dd-cfDNA.

Monitoring Immunosuppression

De Vlaminck et al. demonstrated a close association between plasma cfDNA and a patient’s degree of immunosuppression post-transplant using plasma anellovirus abundance as a surrogate marker of immunosuppression [50]. Adequate immunosuppression is poised to reduce allograft injury and the risk of AR. Thus, %dd-cfDNA could theoretically assist clinicians in understanding the relative degree of immunosuppression when interpreted alongside traditional laboratory markers. Charya et al. recently tested this hypothesis in the GRAfT cohort. They showed a significant inverse correlation of %dd-cfDNA with both tacrolimus trough concentrations and anellovirus abundance, a recognized surrogate marker of global immunosuppression over time [52]. Percent dd-cfDNA identified episodes of inadequate immunosuppression with higher performance compared to both tacrolimus troughs and anellovirus abundance.

Adoption of %dd-cfDNA in Routine Clinical Practice

Three CLIA-approved centralized commercial dd-cfDNA tests are available in the US and Europe: AlloSure (CareDx), Prospera (Natera), and TRAC (Eurofins Viracor) [20, 41]. These tests perform %dd-cfDNA testing without the need for prior genotyping. While these assays show considerable agreement in detecting rejection, the cutoff values are different [53]. CareDx also markets a more decentralized testing kit (CE-IVDD) that utilizes custom SNP panels and PCR. Direct comparison of CE-IVDD with a a centralized assay assay demonstrated positive correlation and reproducibility [10]. However, CE-IVDD has a higher assay detection limit, which could reduce its sensitivity, particularly for heart transplants where lower threshold values are needed for diagnosis of AR.

Clinical adopters of %dd-cfDNA often follow variable monitoring protocols given the lack of consensus standards. A recent editorial summarizes common monitoring protocols used in recent years including the ALARM study, which used %dd-cfDNA thresholds of 0.5% and 1% [24, 54]. They found that %dd-cfDNA values above 1% were highly suggestive of AR and served as an “alarm signal”, or a trigger to biopsy and perform additional testing to identify a cause of the derangement. On the other hand, values below 0.5% provide reassurance as an “all clear” signal. Values between 0.5% and 1% represent a gray zone and could serve as an indication for careful monitoring to detect early or impending forms of complications. In light of these results, a recent meta-analysis showed consistency upon review, giving users more guidance on application of %dd-cfDNA although further studies to describe optimal testing windows are still needed [55].

Gaps in Knowledge

Despite the robust performance of %dd-cfDNA in cohort studies, reports from routine clinical practice show conflicting %dd-cfDNA results, which suggest unaddressed gaps [20, 41, 56]. For example, while replicate analysis demonstrates reproducibility across laboratories, technicians, and platforms, %dd-cfDNA unfortunately presumes stable rd-cfDNA levels post-transplant, which is its first blind spot [57]. This blind spot is particularly problematic, as rd-cfDNA levels can surge and show variable levels after transplantation [21, 58–60]. Any variability therefore results in false-negative or false-positive %dd-cfDNA values independent of the state of allograft injury. Some centers have included absolute dd-cfDNA levels in addition to % to minimize this concern. However, there are significant interindividual differences in dd-cfDNA levels, which can limit its utility [18, 29, 31, 61, 62].

Commercial assays use different %dd-cfDNA thresholds for AR detection, making it challenging to compare results across commercial assays - a 2nd blind spot [10, 63]. There are also no internal control standards to enable comparison between commercial tests. These limitations, plus the paucity of consensus clinical guidelines limit uniform %dd-cfDNA adoption across centers, a 3rd blind spot [20, 41]. Therefore, clinicians and scientists are left to determine their own significant %dd-cfDNA cutoffs for research and clinical purposes. Despite a growing body of evidence for use of %dd-cfDNA, there still remains no uniformly accepted decision-making process published to guide clinician use [2, 8, 64]. Clearly, a standardized approach to research methodology and data validation is required to implement dd-cfDNA beyond its current state, highlighting a key next step towards widespread adoption for transplant care.

%dd-cfDNA testing also lacks specificity for AMR and ACR or between AR and infection–a 4th blind spot. This is a critical shortcoming, as the therapeutic approach to manage ACR, AMR, and various infectious processes differs substantially, with delays or misclassification leading to irreversible allograft injury [23]. A future-ready cfDNA platform could overcome this limitation by coupling quantitative measures from multiple cfDNA compartments - including donor-derived, recipient-derived, and the novel cfDNA testing outlined below - with molecular fingerprints of etiology to produce separate probability scores for AMR and ACR compared to active infection.

Given the limitations outlined above, the emerging field of recipient-derived cfDNA offers a particularly promising avenue for a more holistic approach to post-transplant monitoring. This process may elucidate differences of %dd-cfDNA performance between cohorts and provide inferences to personalize test performance. Only a handful of studies have examined this dimension including our own recent work demonstrating that elevated recipient-derived cfDNA in the early post-transplant period is strongly associated with mortality, AR, and impaired lung function–likely reflecting a systemic injury phenotype that influences the host immune response [44, 65]. In the future, integrating donor and recipient-derived cfDNA into a unified graft–host injury map could quantify both local immune assault and broader physiologic stress, identifying patients at the highest risk for complications such as primary graft dysfunction, secondary infections, or chronic allograft dysfunction long before overt clinical decline.

Do we need randomized control trials (RCTs) in the cfDNA space? There is fear that RCTs, given their high cost, difficulty in achieving enrollment and study benchmarks, could divert resources away from other important discoveries. Well-designed cohort studies have often produced reliable clinical data, particularly in rare diseases as transplantation, without the need for RCTs. However, in the case of %dd-cfDNA, mixed clinical experience compels the need for randomized trials to provide guidelines. A proposed study design for such a trial has been proposed but not yet clinically validated [66]. Any future RCT should ideally address the well-characterized blind spots of %dd-cfDNA to guide proper implementation and adoption into routine clinical practice.

Next Generation cfDNA Approaches Coming to Transplant Medicine

Cell-free Nucleic Acids

The human body is complex and composed of various cells, tissues, and organ types, each with specialized functions. Single-cell genetic, transcriptomic, and epigenetic profiling have enabled the comprehensive characterization of cell populations in multiple tissue types–including rare cell types–during both physiologic and diseased states. Advances in next-generation sequencing technologies and computational tools have revolutionized the characterization of the genome, epigenome, and transcriptomic profiles of circulating nucleic acids. This allows researchers to better understand different diseases and pathways related to the disease, and aid in establishing diagnostic methods and therapeutic targets. Cell-free DNA carries genetic, epigenetic, and fragmentomic information related to tissues-of-origin and disease biology.

Cell-Free RNA

Plasma cfRNA opens a window to capture systemic response, systemic injury, and molecular mechanisms [67]. In addition to traditional RNAs, circulating cfRNA consists of a variety of cfRNA molecules such as microRNAs (miRNAs), short noncoding RNAs (sncRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and others that regulate gene expression. Recent studies used circulating messenger RNA to identify risk of preeclampsia in pregnant women and phenotype cancer subtypes [68–70]. There are limited studies on the use of cfRNA in transplantation. Previous studies focused on miRNAs and the results are conflicting [71, 72]. Nonetheless, we believe plasma cfRNA characterization may reveal pathological processes in previously inaccessible organs [73, 74].

DNA Methylation

Cells show unique epi-methylation markers that play vital roles in genetic regulation with patterns that are unique and stable to each cell type [75]. Recent studies have leveraged cell or tissue specific DNA methylomic markers to identify the tissue origin of cfDNA [76–78]. Microarray- or whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) based methods have also successfully been used [79, 80]. While microarrays require high sample input and cover a small percentage of the total methylation site of interest, WGBS, after bisulfite conversion, surveys the methylation state of all cytosines residues and is considered the gold standard. Reference-based deconvolution libraries have continued to grow from an atlas of 25 human cells or tissues to more than 39 cell or tissue types in a recent study [79, 80]. Despite these advances, studies exploring differential methylation regions from cfDNA in transplant settings are scarce. Furthermore, transplant patients are exposed to combinations of immunosuppressive drugs daily, which may cause epigenetic changes that may lead to undesirable outcomes. Therefore, cfDNA methylome analysis may be an additional tool to identify genes and pathways related to AR.

Cell-Free Histone Modifications

Plasma cfDNA from cell nuclei is wrapped around histone proteins H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 to form an octamer protein called nucleosome, a basic unit of chromatin. Epigenetic profiles of histones, such as mono-methylation of lysine 4 at histone H3 (H3K4me1; enhancer region), carry information related to tissues-of-origin and disease biology. Sadeh et al. recently performed cell-free chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (cfChIP-seq) targeting H3K4me3 to delineate gene expression patterns and subsequently enabled the identification of unique biological pathways linked to common disease conditions [81]. Similar studies in cancer biology report similar performance [82, 83]. In heart transplantation, cfChIP-seq demonstrated reliable gene expression signals for immunosuppression therapy including those in the calcineurin and mTOR signaling pathway [52]. This technique may hold significant potential to distinguish between ACR and AMR phenotypes and elucidate genes or molecular pathways associated with rejection for potential therapeutic targets.

Cell-Free DNA Fragmentomics

cfDNA fragmentation is non-random and regulated by chromatin structure and epigenetic modification. Fragmentation patterns also vary by the cfDNA tissue source and could infer disease biology [84]. Various cell death mechanisms–such as apoptosis, necrosis, autophagy, necroptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and NETosis–as well as active secretion, contribute distinct pools of cfDNA. Nucleosome positioning controls transcription by restricting access to the target DNA region [85]. Recent studies have leveraged nucleosome positioning to identify tissue origin of cfDNA and decipher gene expression profiles in cells contributing to cfDNA pools [86, 87]. Use of similar techniques in transplant patients could offer further insight into the unique transplant genetic environment and gene expression pathways.

Cell-Free Mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondria are found in varying numbers and shapes within human cells and differ among cell and tissue type, reflecting metabolic and bioenergetic demands. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is highly susceptible to oxidative damage due to its poor ability to repair its own DNA [88]. Therefore, during cellular injury, mtDNA is released into the extracellular environment as circulating mt-cfDNA and contribute to the circulating cfDNA pool [89]. A number of studies have reported that increased plasma levels of mtcfDNA in transplant settings can serve as markers of mitochondrial or cell damage, as well as predict allograft dysfunction or episodes of rejection [90–93]. Additionally Ma et al.’s showed that both linear and circular mtDNA coexist in the plasma of liver transplant patients, and as such, both may provide different biological information [94]. Studies characterizing the mt-cfDNA fragment size distribution released from the allograft and recipient tissues may provide new disease-related information.

Future Directions

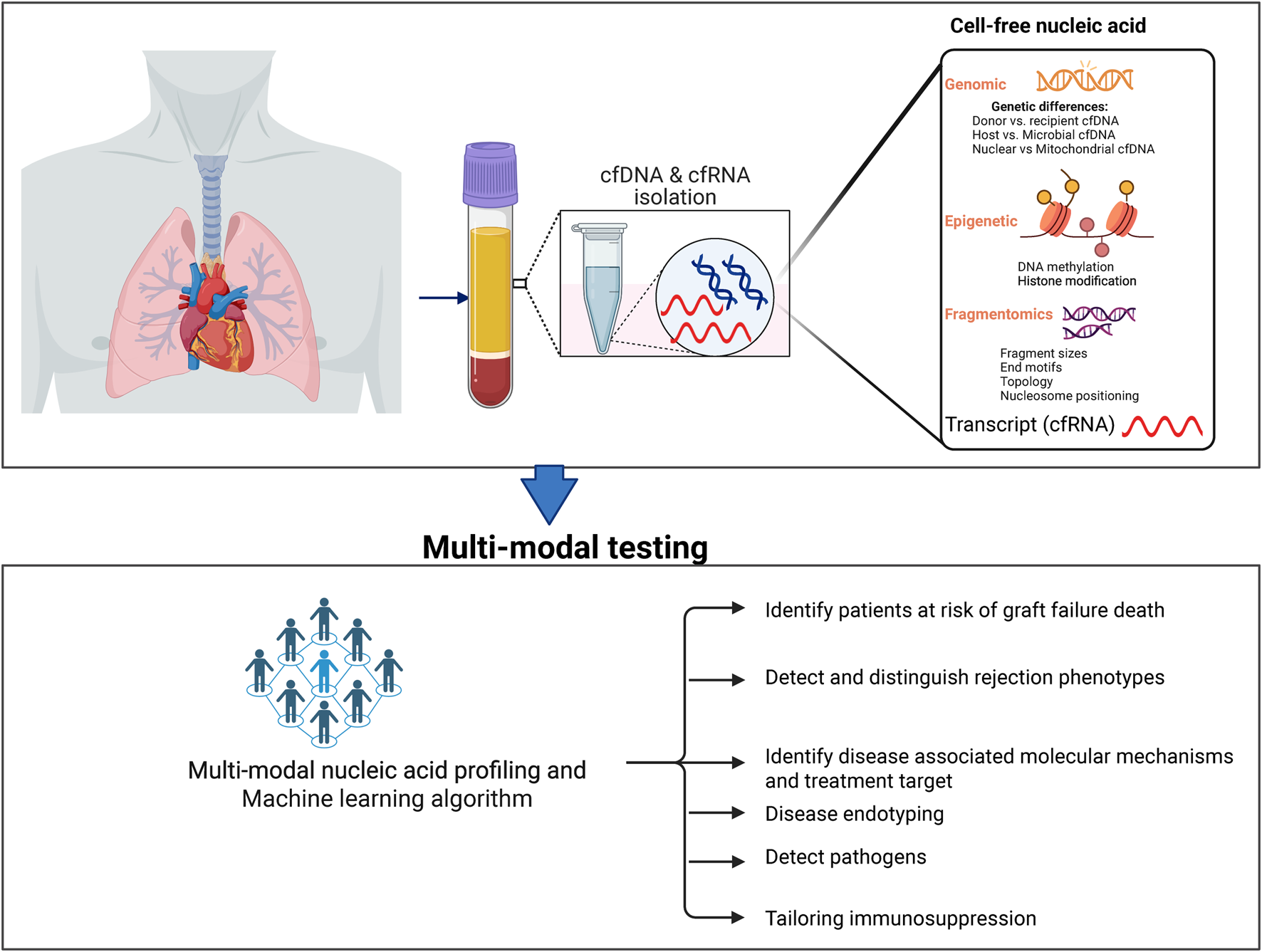

Figure 2 summarizes the diagnostic potential of %dd-cfDNA and novel technologies discussed. %dd-cfDNA has shown significant results in well-structured cohort studies [18, 43]. However, the mixed results from routine clinical experiences suggest the need for additional studies to address the blind spots and gaps in the dd-cfDNA test [15]. Notably, given the wide variability in host cfDNA levels between patients, it is essential to revisit the effectiveness of %dd-cfDNA across diverse populations, considering personal factors that may impact performance [44]. There is also a need to establish decentralized testing with robust internal controls to enable reproducibility between labs.

FIGURE 2

Novel cfDNA and the future diagnostic utility in transplantation.

Looking ahead, the promise of cfDNA lies in integrating different modalities. Embedding the readouts of these modalities into adaptive algorithms–especially when augmented by pharmacogenomics, immune monitoring, and AI-enabled prediction–could shift practice. For example, this approach could shift immunosuppression from empiric population-based regimens to an individualized, real-time management model. The ultimate vision is a precision-guided strategy where one test informs whether to intensify, taper, or redirect therapy, thereby reducing rejection, infection, and drug toxicity while improving long-term graft survival. While this promise may be a mere dream today, we have summarized novel cfDNA approaches that offer advantages to address these gaps. We anticipate that these new technologies could move transplant monitoring away from the one-size-fits-all paradigm towards a more individualized approach.

Statements

Author contributions

SA-E received invitation and defined content. S-AE, EF, NN, TA, and MA contributed to writing, and editing the manuscript. NN and TA produced Figures and Tables. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. SA-E Laboratory of Applied Precision Omics. This includes funding from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (AGBORE20QI0), the Anne Theodore Foundation, the National Institute of Health Distinguished Scholar Program and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Division of Intramural Research.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Author disclaimer

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The contributions of the NIH authors are considered Works of the United States Government. The findings and conclusions presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

References

1.

ChristieJDVan RaemdonckDFisherAJ. Lung Transplantation. N Engl J Med (2024) 391(19):1822–36. 10.1056/NEJMra2401039

2.

VellecaAShulloMADhitalKAzekaEColvinMDePasqualeEet alThe International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Guidelines for the Care of Heart Transplant Recipients. J Heart Lung Transpl (2023) 42(5):e1–e141. 10.1016/j.healun.2022.10.015

3.

LampertBCTeutebergJJShulloMAHoltzJSmithKJ. Cost-Effectiveness of Routine Surveillance Endomyocardial Biopsy After 12 Months Post-Heart Transplantation. Circ Heart Fail (2014) 7(5):807–13. 10.1161/circheartfailure.114.001199

4.

HolzmannMNickoAKühlUNoutsiasMPollerWHoffmannWet alComplication Rate of Right Ventricular Endomyocardial Biopsy via the Femoral Approach. Circulation (2008) 118(17):1722–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743427

5.

BhoradeSMHusainANLiaoCLiLCAhyaVNBazMAet alInterobserver Variability in Grading Transbronchial Lung Biopsy Specimens After Lung Transplantation. Chest (2013) 143(6):1717–24. 10.1378/chest.12-2107

6.

ButlerCRSavuABakalJATomaMThompsonRChowKet alCorrelation of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings and Endomyocardial Biopsy Results in Patients Undergoing Screening for Heart Transplant Rejection. J Heart Lung Transpl (2015) 34(5):643–50. 10.1016/j.healun.2014.12.020

7.

Jiménez-CollVEl Kaaoui El BandJLlorenteSGonzález-LópezRFernández-GonzálezMMartínez-BanaclochaHet alAll that Glitters in cfDNA Analysis Is Not Gold or Its Utility Is Completely Established Due to Graft Damage: A Critical Review in the Field of Transplantation. Diagnostics (Basel) (2023) 13(12):1982. 10.3390/diagnostics13121982

8.

NikolovaAAgbor-EnohSBosSCrespo-LeiroMEnsmingerSJimenez-BlancoMet alEuropean Society for Organ Transplantation (ESOT) Consensus Statement on the Use of Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Cardiothoracic Transplant Rejection Surveillance. Transpl Int (2024) 37:12445. 10.3389/ti.2024.12445

9.

AubertOUrsule-DufaitCBrousseRGueguenJRacapéMRaynaudMet alCell-Free DNA for the Detection of Kidney Allograft Rejection. Nat Med (2024) 30(8):2320–7. 10.1038/s41591-024-03087-3

10.

LoupyACertainATangprasertchaiNSRacapéMUrsule-DufaitCBenbadiKet alEvaluation of a Decentralized Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Assay for Kidney Allograft Rejection Monitoring. Transpl Int (2024) 37:13919. 10.3389/ti.2024.13919

11.

SinduDBayCGriefKWaliaRTokmanS. Clinical Utility of Plasma Percent Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA for Lung Allograft Surveillance: A Real-World Single-Center Experience. JHLT Open (2024) 6:100141. 10.1016/j.jhlto.2024.100141

12.

KimPJOlympiosMSiderisKTseliouETranTYCarterSet alA Two-Threshold Algorithm Using Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Fraction and Quantity to Detect Acute Rejection After Heart Transplantation. Am J Transplant (2025) 25(9):1895–905. 10.1016/j.ajt.2025.04.021

13.

LoYMCorbettaNChamberlainPFRaiVSargentILRedmanCWet alPresence of Fetal DNA in Maternal Plasma and Serum. Lancet (1997) 350(9076):485–7. 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)02174-0

14.

SnyderTMKhushKKValantineHAQuakeSR. Universal Noninvasive Detection of Solid Organ Transplant Rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2011) 108(15):6229–34. 10.1073/pnas.1013924108

15.

SebastianASilvyMCoiffardBReynaud-GaubertMMagdinierFChiaroniJet alA Review of Cell-Free DNA and Epigenetics for Non-Invasive Diagnosis in Solid Organ Transplantation. Front Transplant (2024) 3:1474920. 10.3389/frtra.2024.1474920

16.

De VlaminckIValantineHASnyderTMStrehlCCohenGLuikartHet alCirculating Cell-Free DNA Enables Noninvasive Diagnosis of Heart Transplant Rejection. Sci Transl Med (2014) 6(241):241ra77. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007803

17.

KhushKKPatelJPinneySKaoAAlharethiRDePasqualeEet alNoninvasive Detection of Graft Injury After Heart Transplant Using Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Am J Transplant (2019) 19(10):2889–99. 10.1111/ajt.15339

18.

Agbor-EnohSShahPTuncIHsuSRussellSFellerEet alCell-Free DNA to Detect Heart Allograft Acute Rejection. Circulation (2021) 143(12):1184–97. 10.1161/circulationaha.120.049098

19.

KnüttgenFBeckJDittrichMOellerichMZittermannASchulzUet alGraft-Derived Cell-Free DNA as a Noninvasive Biomarker of Cardiac Allograft Rejection: A Cohort Study on Clinical Validity and Confounding Factors. Transplantation (2022) 106(3):615–22. 10.1097/tp.0000000000003725

20.

KimPJOlymbiosMSiuAWever PinzonOAdlerELiangNet alA Novel Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Assay for the Detection of Acute Rejection in Heart Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl (2022) 41(7):919–27. 10.1016/j.healun.2022.04.002

21.

BöhmerJWåhlanderHTran-LundmarkKOdermarskyMAlpmanMSAspJet alAbsolute Quantification of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Following Pediatric and Adult Heart Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl (2025) 44:1638–47. 10.1016/j.healun.2025.04.024

22.

De VlaminckIMartinLKerteszMPatelKKowarskyMStrehlCet alNoninvasive Monitoring of Infection and Rejection After Lung Transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2015) 112(43):13336–41. 10.1073/pnas.1517494112

23.

JangMKTuncIBerryGJMarboeCKongHKellerMBet alDonor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Accurately Detects Acute Rejection in Lung Transplant Patients, a Multicenter Cohort Study. J Heart Lung Transpl (2021) 40(8):822–30. 10.1016/j.healun.2021.04.009

24.

KellerMSunJMutebiCShahPLevineDAryalSet alDonor-Derived Cell-Free DNA as a Composite Marker of Acute Lung Allograft Dysfunction in Clinical Care. J Heart Lung Transpl (2022) 41(4):458–66. 10.1016/j.healun.2021.12.009

25.

RosenheckJPRossDJBotrosMWongASternbergJChenYAet alClinical Validation of a Plasma Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Assay to Detect Allograft Rejection and Injury in Lung Transplant. Transplant Direct (2022) 8(4):e1317. 10.1097/txd.0000000000001317

26.

JuCWangLXuPWangXXiangDXuYet alDifferentiation Between Lung Allograft Rejection and Infection Using Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA and Pathogen Detection by Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing. Heliyon (2023) 9(11):e22274. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22274

27.

Agbor-EnohSJacksonAMTuncIBerryGJCochraneAGrimmDet alLate Manifestation of Alloantibody-Associated Injury and Clinical Pulmonary Antibody-Mediated Rejection: Evidence from Cell-Free DNA Analysis. J Heart Lung Transpl (2018) 37(7):925–32. 10.1016/j.healun.2018.01.1305

28.

JuCXuXZhangJChenALianQLiuFet alApplication of Plasma Donor-Derived Cell Free DNA for Lung Allograft Rejection Diagnosis in Lung Transplant Recipients. BMC Pulm Med (2023) 23(1):37. 10.1186/s12890-022-02229-y

29.

KhushKKDe VlaminckILuikartHRossDJNicollsMR. Donor-Derived, Cell-Free DNA Levels by Next-Generation Targeted Sequencing are Elevated in Allograft Rejection After Lung Transplantation. ERJ Open Res (2021) 7(1):00462-2020. 10.1183/23120541.00462-2020

30.

NodaKSnyderMEXuQPetersDMcDyerJFZeeviAet alSingle Center Study Investigating the Clinical Association of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA with Acute Outcomes in Lung Transplantation. Front Transplant (2023) 2:1339814. 10.3389/frtra.2023.1339814

31.

TrindadeAJChapinKCGrayJNFuruyaYMullicanAHoyHet alRelative Change in Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Is Superior to Absolute Values for Diagnosis of Acute Lung Allograft Dysfunction. Transplant Direct (2023) 9(6):e1487. 10.1097/txd.0000000000001487

32.

BazemoreKPermpalungNMathewJLemmaMHaileBAveryRet alElevated Cell-Free DNA in Respiratory Viral Infection and Associated Lung Allograft Dysfunction. Am J Transplant (2022) 22(11):2560–70. 10.1111/ajt.17125

33.

SmithJBPetersonRAPomponioRSteeleMGrayAL. Donor Derived Cell Free DNA in Lung Transplant Recipients Rises in Setting of Allograft Instability. Front Transplant (2024) 3:1497374. 10.3389/frtra.2024.1497374

34.

NovoMNordénRWestinJDellgrenGBöhmerJRickstenAet alDonor Fractions of Cell-Free DNA Are Elevated During CLAD But Not During Infectious Complications After Lung Transplantation. Transpl Int (2024) 37:12772. 10.3389/ti.2024.12772

35.

Van MuylemAMélotCAntoineMKnoopCEstenneM. Role of Pulmonary Function in the Detection of Allograft Dysfunction After Heart-Lung Transplantation. Thorax (1997) 52(7):643–7. 10.1136/thx.52.7.643

36.

WijtvlietVPlaekePAbramsSHensNGielisEMHellemansRet alDonor-Derived Cell-Free DNA as a Biomarker for Rejection After Kidney Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transpl Int (2020) 33(12):1626–42. 10.1111/tri.13753

37.

RichmondMEDeshpandeSRZangwillSDBichellDPKindelSJMahleWTet alValidation of Donor Fraction Cell-Free DNA with Biopsy-Proven Cardiac Allograft Rejection in Children and Adults. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg (2023) 165(2):460–8.e2. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2022.04.027

38.

HanDMillerRJHOtakiYGransarHKransdorfEHamiltonMet alDiagnostic Accuracy of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance for Cardiac Transplant Rejection. JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging (2021) 14(12):2337–49. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2021.05.008

39.

MoellerCMOrenDFernandez ValledorARubinsteinGDeFilippisEMRahmanSet alElevated Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Levels Are Associated with Reduced Myocardial Blood Flow but Not Angiographic Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy: The EVIDENT Study. Circ Heart Fail (2025) 18(1):e011756. 10.1161/circheartfailure.124.011756

40.

MoellerCMFernandez ValledorAOrenDRahmanSBaranowskaJHertzAet alSignificance of Elevated Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA in Heart Transplant Recipients with Negative Endomyocardial Biopsies: A Dawn of a New Era. Circ Heart Fail (2025) 18:e012787. 10.1161/circheartfailure.125.012787

41.

Jiménez-BlancoMCrespo-LeiroMGGarcía-Cosío CarmenaMDGómez BuenoMLópez-VilellaROrtiz-BautistaCet alDonor-Derived Cell-Free DNA as a New Biomarker for Cardiac Allograft Rejection: A Prospective Study (FreeDNA-CAR). J Heart Lung Transpl (2025) 44(4):560–9. 10.1016/j.healun.2024.11.009

42.

BalasubramanianSRichertMEKongHFuSJangMKAndargieTEet alCell-Free DNA Maps Tissue Injury and Correlates with Disease Severity in Lung Transplant Candidates. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2024) 209(6):727–37. 10.1164/rccm.202306-1064OC

43.

Agbor-EnohSWangYTuncIJangMKDavisADe VlaminckIet alDonor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Predicts Allograft Failure and Mortality After Lung Transplantation. EBioMedicine (2019) 40:541–53. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.12.029

44.

AlnababtehMKellerMBKongHPhippsKNamianJPonorLet alEarly Post-Transplant Recipient Tissue Injury Predicts Allograft Function, Rejection, and Survival in Lung Transplant Recipients, Evidence from Cell-Free DNA. Eur Respir J (2025):2402537. 10.1183/13993003.02537-2024

45.

KellerMBNewmanDAlnababtehMPonorLShahPMathewJet alExtreme Elevations of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Increases the Risk of Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction and Death, Even Without Clinical Manifestations of Disease. J Heart Lung Transpl (2024) 43(9):1374–82. 10.1016/j.healun.2024.04.064

46.

KellerMBTianXJangMKMedaRCharyaABerryGJet alHigher Molecular Injury at Diagnosis of Acute Cellular Rejection Increases the Risk of Lung Allograft Failure: A Clinical Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2024) 209(10):1238–45. 10.1164/rccm.202305-0798OC

47.

KellerMBSunJAlnababtehMPonorLPDSMathewJet alBaseline Lung Allograft Dysfunction After Bilateral Lung Transplantation Is Associated with an Increased Risk of Death: Results from a Multicenter Cohort Study. Transplant Direct (2024) 10(7):e1669. 10.1097/txd.0000000000001669

48.

KellerMBTianXJangMKMedaRCharyaAOzisikDet alOrganizing Pneumonia Is Associated with Molecular Allograft Injury and the Development of Antibody-Mediated Rejection. J Heart Lung Transpl (2024) 43(4):563–70. 10.1016/j.healun.2023.11.008

49.

BlauwkampTAThairSRosenMJBlairLLindnerMSVilfanIDet alAnalytical and Clinical Validation of a Microbial Cell-Free DNA Sequencing Test for Infectious Disease. Nat Microbiol (2019) 4(4):663–74. 10.1038/s41564-018-0349-6

50.

De VlaminckIKhushKKStrehlCKohliBLuikartHNeffNFet alTemporal Response of the Human Virome to Immunosuppression and Antiviral Therapy. Cell (2013) 155(5):1178–87. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.034

51.

ShahJRSohailMRLascoTGossJAMohajerMAKhalilS. Clinical Utility of Plasma Microbial Cell-Free DNA Sequencing in Determining Microbiologic Etiology of Infectious Syndromes in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Ther Adv Infect Dis (2024) 11:20499361241308643. 10.1177/20499361241308643

52.

CharyaAVJangMKKongHParkWTianXKellerMet alDonor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Is Associated with the Degree of Immunosuppression in Lung Transplantation. Am J Transplant (2025) 25:1906–15. 10.1016/j.ajt.2025.04.011

53.

HsiBVan ZylJAlamKShakoorHFarsakhDAlamAet alTale of Two Assays: Comparison of Modern Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Technologies. JHLT Open (2024) 4:100090. 10.1016/j.jhlto.2024.100090

54.

MackintoshJAChambersDC. Genomic Lung Allograft Surveillance-Is It Primer Time?J Heart Lung Transpl (2022) 41(4):467–9. 10.1016/j.healun.2022.01.016

55.

LiYLiangB. Circulating Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA as a Marker for Rejection After Lung Transplantation. Front Immunol (2023) 14:1263389. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1263389

56.

BloomRDBrombergJSPoggioEDBunnapradistSLangoneAJSoodPet alCell-Free DNA and Active Rejection in Kidney Allografts. J Am Soc Nephrol (2017) 28(7):2221–32. 10.1681/asn.2016091034

57.

Agbor-EnohSTuncIDe VlaminckIFideliUDavisACuttinKet alApplying Rigor and Reproducibility Standards to Assay Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA as a Non-Invasive Method for Detection of Acute Rejection and Graft Injury After Heart Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl (2017) 36(9):1004–12. 10.1016/j.healun.2017.05.026

58.

Paunel-GörgülüAWackerMEl AitaMHassanSSchlachtenbergerGDeppeAet alcfDNA Correlates with Endothelial Damage After Cardiac Surgery with Prolonged Cardiopulmonary Bypass and Amplifies NETosis in an Intracellular TLR9-Independent Manner. Scientific Rep (2017) 7(1):17421. 10.1038/s41598-017-17561-1

59.

SchützEAsendorfTBeckJSchauerteVMettenmeyerNShipkovaMet alTime-Dependent Apparent Increase in dd-cfDNA Percentage in Clinically Stable Patients Between One and Five Years Following Kidney Transplantation. Clin Chem (2020) 66(10):1290–9. 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa175

60.

FilipponeEJFarberJL. The Monitoring of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA in Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation (2021) 105(3):509–16. 10.1097/tp.0000000000003393

61.

ShahPAgbor-EnohSLeeSAndargieTESinhaSSKongHet alRacial Differences in Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA and Mitochondrial DNA After Heart Transplantation, on Behalf of the GRAfT Investigators. Circ Heart Fail (2024) 17(4):e011160. 10.1161/circheartfailure.123.011160

62.

KellerMBMedaRFuSYuKJangMKCharyaAet alComparison of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Between Single Versus Double Lung Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant (2022) 22(10):2451–7. 10.1111/ajt.17039

63.

OellerichMSherwoodKKeownPSchützEBeckJStegbauerJet alLiquid Biopsies: Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA for the Detection of Kidney Allograft Injury. Nat Rev Nephrol (2021) 17(9):591–603. 10.1038/s41581-021-00428-0

64.

SchultzJStehlikJ. Emergence of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Monitoring for Heart Transplant: Future of Rejection Surveillance. Am Coll Cardiol (2022).

65.

ZajacovaAAlkhouriMFerraoGGuneyMRezacDVyskocilovaKet alEarly Post-Lung Transplant Cell-Free DNA Levels are Associated with Baseline Lung Allograft Function. Transpl Immunol (2025) 92:102245. 10.1016/j.trim.2025.102245

66.

KellerMRossDBhoradeSAgbor-EnohS. (1187) Study Design for a Randomized Control Trial of Lung Allograft Monitoring with Blood Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Assessments (LAMBDA 001). The J Heart Lung Transplant (2023) 42(4, Suppl. ment):S509. 10.1016/j.healun.2023.02.1398

67.

VorperianSKMoufarrejMNQuakeSR. Cell Types of Origin of the Cell-Free Transcriptome. Nat Biotechnol (2022) 40(6):855–61. 10.1038/s41587-021-01188-9

68.

AlbrechtLJHöwnerAGriewankKLueongSSvon NeuhoffNHornPAet alCirculating Cell-Free Messenger RNA Enables Non-Invasive Pan-Tumour Monitoring of Melanoma Therapy Independent of the Mutational Genotype. Clin Transl Med (2022) 12(11):e1090. 10.1002/ctm2.1090

69.

LarsonMHPanWKimHJMauntzREStuartSMPimentelMet alA Comprehensive Characterization of the Cell-Free Transcriptome Reveals Tissue- and Subtype-Specific Biomarkers for Cancer Detection. Nat Commun (2021) 12(1):2357. 10.1038/s41467-021-22444-1

70.

MoufarrejMNVorperianSKWongRJCamposAAQuaintanceCCSitRVet alEarly Prediction of Preeclampsia in Pregnancy with Cell-Free RNA. Nature (2022) 602(7898):689–94. 10.1038/s41586-022-04410-z

71.

ShahPAgbor-EnohSBagchiPdeFilippiCRMercadoADiaoGet alCirculating microRNAs in Cellular and Antibody-Mediated Heart Transplant Rejection. J Heart Lung Transpl (2022) 41(10):1401–13. 10.1016/j.healun.2022.06.019

72.

CoutanceGRacapéMBaudryGLécuyerLRoubilleFBlanchartKet alValidation of the Clinical Utility of microRNA as Noninvasive Biomarkers of Cardiac Allograft Rejection: A Prospective Longitudinal Multicenter Study. J Heart Lung Transpl (2023) 42(11):1505–9. 10.1016/j.healun.2023.07.010

73.

DomínguezCCXuCJarvisLBRainbowDBWellsSBGomesTet alCross-Tissue Immune Cell Analysis Reveals Tissue-Specific Features in Humans. Science (2022) 376(6594):eabl5197. 10.1126/science.abl5197

74.

ZhuangJIbarraAAcostaAKarnsAPAballiJNerenbergMet alSurvey of Extracellular Communication of Systemic and Organ-Specific Inflammatory Responses Through Cell Free Messenger RNA Profiling in Mice. EBioMedicine (2022) 83:104242. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104242

75.

PortelaAEstellerM. Epigenetic Modifications and Human Disease. Nat Biotechnology (2010) 28(10):1057–68. 10.1038/nbt.1685

76.

AndargieTERoznikKRedekarNHillTZhouWApalaraZet alCell-Free DNA Reveals Distinct Pathology of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children. J Clin Invest (2023) 133(21):e171729. 10.1172/jci171729

77.

ChengAPChengMPGuWSesing LenzJHsuESchurrEet alCell-Free DNA Tissues of Origin by Methylation Profiling Reveals Significant Cell, Tissue, and Organ-Specific Injury Related to COVID-19 Severity. Med (2021) 2(4):411–22.e5. 10.1016/j.medj.2021.01.001

78.

AndargieTETsujiNSeifuddinFJangMKYuenPSKongHet alCell-Free DNA Maps COVID-19 Tissue Injury and Risk of Death and Can Cause Tissue Injury. JCI Insight (2021) 6(7):e147610. 10.1172/jci.insight.147610

79.

MossJMagenheimJNeimanDZemmourHLoyferNKorachAet alComprehensive Human Cell-Type Methylation Atlas Reveals Origins of Circulating Cell-Free DNA in Health and Disease. Nat Communications (2018) 9(1):1–12. 10.1038/s41467-018-07466-6

80.

LoyferNMagenheimJPeretzACannGBrednoJKlochendlerAet alA DNA Methylation Atlas of Normal Human Cell Types. Nature (2023) 613(7943):355–64. 10.1038/s41586-022-05580-6

81.

SadehRSharkiaIFialkoffGRahatAGutinJChappleboimAet alChIP-seq of Plasma Cell-Free Nucleosomes Identifies Gene Expression Programs of the Cells of Origin. Nat Biotechnology (2021) 39:1–13. 10.1038/s41587-020-00775-6

82.

Vad-NielsenJMeldgaardPSorensenBSNielsenAL. Cell-Free Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (cfChIP) from Blood Plasma Can Determine Gene-Expression in Tumors from Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Lung Cancer (2020) 147:244–51. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.07.023

83.

TrierMCMeldgaardPStougaardMNielsenALSorensenBS. Cell-Free Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Can Determine Tumor Gene Expression in Lung Cancer Patients. Mol Oncol (2023) 17(5):722–36. 10.1002/1878-0261.13394

84.

LiuY. At the Dawn: Cell-Free DNA Fragmentomics and Gene Regulation. Br J Cancer (2022) 126(3):379–90. 10.1038/s41416-021-01635-z

85.

Suárez-ÁlvarezBBaragaño RanerosAOrtegaFLópez-LarreaC. Epigenetic Modulation of the Immune Function: A Potential Target for Tolerance. Epigenetics (2013) 8(7):694–702. 10.4161/epi.25201

86.

UlzPThallingerGGAuerMGrafRKashoferKJahnSWet alInferring Expressed Genes by Whole-Genome Sequencing of Plasma DNA. Nat Genetics (2016) 48(10):1273–8. 10.1038/ng.3648

87.

SchübelerD. Function and Information Content of DNA Methylation. Nature (2015) 517(7534):321–6. 10.1038/nature14192

88.

LarsenNBRasmussenMRasmussenLJ. Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Repair: Similar Pathways?Mitochondrion (2005) 5(2):89–108. 10.1016/j.mito.2005.02.002

89.

MontierLLCDengJJBaiY. Number Matters: Control of Mammalian Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number. J Genetics Genomics (2009) 36(3):125–31. 10.1016/s1673-8527(08)60099-5

90.

YoshinoOWongBKLCoxDRALeeEHepworthGChristophiCet alElevated Levels of Circulating Mitochondrial DNA Predict Early Allograft Dysfunction in Patients Following Liver Transplantation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol (2021) 36(12):3500–7. 10.1111/jgh.15670

91.

HanFSunQHuangZLiHMaMLiaoTet alDonor Plasma Mitochondrial DNA Is Associated with Antibody-Mediated Rejection in Renal Allograft Recipients. Aging (Albany NY) (2021) 13(6):8440–53. 10.18632/aging.202654

92.

MallaviaBLiuFLefrançaisEClearySJKwaanNTianJJet alMitochondrial DNA Stimulates TLR9-Dependent Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation in Primary Graft Dysfunction. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2020) 62(3):364–72. 10.1165/rcmb.2019-0140OC

93.

SayahDMMallaviaBLiuFOrtiz-MuñozGCaudrillierADerHovanessianAet alNeutrophil Extracellular Traps are Pathogenic in Primary Graft Dysfunction After Lung Transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2015) 191(4):455–63. 10.1164/rccm.201406-1086OC

94.

MaMLZhangHJiangPSinSTKLamWKJChengSHet alTopologic Analysis of Plasma Mitochondrial DNA Reveals the Coexistence of Both Linear and Circular Molecules. Clin Chem. (2019) 65(9):1161–70. 10.1373/clinchem.2019.308122

Summary

Keywords

cfDNA, acute rejection, diagnosis, transplantation, allograft injury

Citation

Agbor-Enoh S, Fraser E, Nadella N, Andargie TE and Alnababteh M (2025) %dd-cfDNA: The New Frontier for Heart/Lung Transplant Surveillance?. Transpl. Int. 38:15555. doi: 10.3389/ti.2025.15555

Received

08 September 2025

Revised

14 November 2025

Accepted

09 December 2025

Published

29 December 2025

Volume

38 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Agbor-Enoh, Fraser, Nadella, Andargie and Alnababteh.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sean Agbor-Enoh, sean.agbor-enoh@nih.gov

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.