Dear Editors,

Letermovir is approved for primary prophylaxis of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in seropositive donor/seronegative kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) [1, 2]. Letermovir inhibits CYP3A4, raising the risk of interactions with calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) and mTOR inhibitors (mTORi) [3]. Real-world data regarding these interactions are limited [4]. This retrospective multicenter study evaluated letermovir-immunosuppressant interactions and assessed letermovir safety and efficacy.

Twenty-six KTRs were included. Detailed methods are provided in the Supplementary Material, and patient characteristics in Supplementary Table S1. Letermovir was initiated at a median of 135 days [IQR: 109–139] post-transplantation for primary prophylaxis (patients with a history of or current valganciclovir resistance or intolerance, n = 5), 264 days [192–397] for curative treatment (n = 11), and 296 days [252–423] for secondary prophylaxis (n = 10). At data cutoff, five patients remained on letermovir; one died of CMV disease and another lost graft function. Among the rest, median treatment duration was 151 days [66–361].

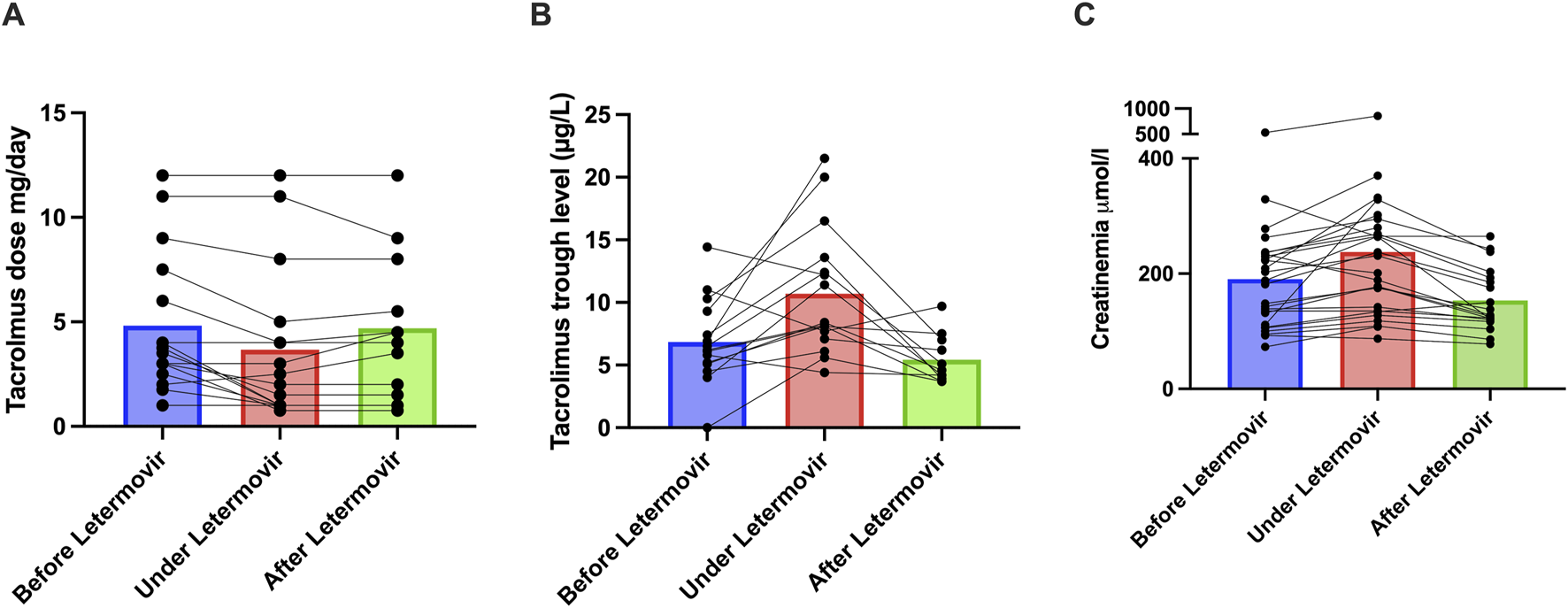

In the 16 patients receiving tacrolimus, the median daily dose significantly decreased from 3.6 mg [2.6–7.1] before letermovir to 2.3 mg [1–4.8] during treatment (p = 0.002, Figure 1A; Supplementary Table S2), corresponding to a median 33% dose reduction (range: 0%–75%). Similar findings have been reported in transplant recipients, with most studies recommending a 30%–50% dose reduction [5–7]. Two patients also receiving CYP3A4 inhibitors (lansoprazole, amiodarone) had among the largest tacrolimus dose reductions—74% and 60%—suggesting a cumulative effect. No association was found between dose reduction and body mass index (Spearman ρ = −0.04, p = 0.87), or with tacrolimus formulation (immediate-release: 33% reduction; melt-dose: 38%; prolonged-release: 0%; p = 0.41). Tacrolimus trough levels significantly increased from a median of 6.2 ng/mL [5.1–9.3] to 8.3 ng/mL [7.3–13.3] during letermovir treatment (p = 0.006, Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1

Impact of Letermovir on Tacrolimus dosage, Tacrolimus residual levels and renal function. (A) Changes in tacrolimus dosage before (n = 16), during (n = 16), and after stopping letermovir (n = 12). (B) Changes in tacrolimus residual levels before (n = 15), during (n = 16), and after stopping letermovir (n = 11). The tacrolimus trough level was below the limit of detection for one patient therefore, a value of zero was assigned. (C) Creatinine in µmol/L before (n = 26), during (n = 26), and after (n = 19) treatment with letermovir. Each dots represents a patient. The plot represents the median (bar).

Among 12 patients with post-letermovir treatment data, tacrolimus daily doses remained stable (3.5 mg [1.6–7.3] vs. 4.3 mg [1.6–7.4], p = 0.88), but trough levels significantly decreased after discontinuation (from 8.1 ng/mL [7.1–12.4] to 7 ng/mL [3.9–7.0], p = 0.01).

In the 5 patients receiving ciclosporin, the median dose decreased from 200 mg/day [125–200] to 100 mg/day [90–200], without reaching statistical significance (p = 0.25). In four patients with available through levels, concentrations increased from 71 ng/mL [55–126] to 169 ng/mL [152–406] (p = 0.13). In three patients with post-letermovir treatment data, doses remained unchanged in two and doubled in one. Notably, previous pharmacokinetic data showed a 1.7-fold increase in ciclosporin AUC with letermovir [3].

Among four patients on everolimus, one discontinued the drug shortly after starting letermovir. In the remaining three, trough levels increased (11.3, 10.8, and 9.1 ng/mL), prompting 50% dose reductions in two cases. In healthy volunteers, letermovir increased everolimus AUC by 3.4-fold [3].

An unanticipated observation was a transient 18% increase in serum creatinine following letermovir initiation from 185 μmol/L [110–235] to 216 μmol/L [135–284] (p = 0.0006), with 17 of 26 patients (65%) meeting KDIGO 1 criteria for acute kidney injury (AKI, defined as a ≥26 μmol/L increase). Seven of them also experienced gastrointestinal side effects that may have led to functional AKI. In 19 patients with post-letermovir treatment data, creatinine increased from 143 μmol/L [107–230] to 178 μmol/L [128–264] during treatment (p = 0.03), and then decreased to 126 μmol/L [120–193] after discontinuation (p = 0.0002), indicating reversibility (Figure 1C). No correlation was found between creatinine increase and tacrolimus peak levels (Spearman ρ = −0.08, p = 0.72), and creatinine elevation occurred also in all five patients not on CNIs (ranging from 28 μmol/L to 123 μmol/L). Possible mechanisms include inhibition of renal tubular OAT3 transporters by letermovir impairing creatinine elimination [8] or gastrointestinal symptoms leading to functional AKI. In the trial by Limaye et al. [9], AKI occurred in only 6.8% of patients receiving letermovir, similar to the valganciclovir group. As letermovir was initiated early post-transplant—when renal function is recovering—minor creatinine increases may have been difficult to detect.

Gastrointestinal adverse events, including diarrhea and vomiting, were reported in 9 patients (35%), consistent with earlier reports [9, 10]. These events were not associated with CNI exposure (7/9 vs. 14/17, p > 0.99) or tacrolimus trough levels (8.3 vs. 9.8 ng/mL, p = 0.7).

Letermovir was used for prophylaxis in 15 patients—10 due to valganciclovir-induced cytopenia and five for a prior history of valganciclovir resistance or poor virologic response. CMV replication occurred in three patients on secondary prophylaxis. Resistance was excluded in one case; two were not tested. These findings support cautious off-label use of letermovir for secondary prophylaxis in select cases [10].

Letermovir was used as curative therapy in 11 patients, mainly for CMV resistant to first-line antivirals (n = 10), and often in combination with other anti-CMV agents (n = 6). Treatment was initiated in a context of low viral load (median 3.49 log10 IU/mL [3.22–3.72]). Two patients experienced viral load increases (from 3.3 to 5.6 log10 IU/mL and from 3.2 to 4.3 log10 IU/mL, respectively), and both developed confirmed letermovir resistance. One of these patients died from CMV disease.

Because letermovir is unapproved for curative therapy and carries a low genetic barrier to resistance, it should only be considered in selected low viral load refractory cases, as a last-resort option in combination with other antiviral agents.

Despite limitations—including retrospective design, small sample size, and lack of standardized therapeutic drug protocols—this study suggests that letermovir use is associated with significant pharmacokinetic interactions with CNIs and mTORi, warranting close drug level monitoring during initiation and discontinuation. Clinicians should also be alert to the potential for renal function decline hopefully reversible.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Patients had provided informed consent for participation in the ASTRE database, which collects clinical and biological data across these centers (DR-2012-518). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

IB, designed the study, collected and analyzed the data and wrote the article. SC designed the study and reviewed the article. BS, CG, FR, CB, GF, CD, and DB collected the data and reviewed the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

IB received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, MSD and Biotest, was on advisory boards for Chiesi, Takeda, and MSD and received travel grants from Chiesi, MSD, AstraZeneca and Biotest. BS was on advisory boards for Chiesi and Takeda. SC received speaker fees from Pfizer, was on advisory boards for Astellas, ALexion, Astra Zeneca, Pierre Fabre, GSK, Chiesi and received travel grants from Alexion, Sanofi and Pierre Fabre.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. CHAT GPT chat bot for english langage editing.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ti.2025.15371/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

European Medicines Agency (n.d). Available online at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/prevymis-epar-product-information_en.pdf (Accessed November 28, 2025).

2.

Food and Drug Administration (n.d). Available online at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/209939s011,209940s010lbl.pdf (Accessed November 28, 2025).

3.

Kropeit D von Richter O Stobernack HP Rübsamen-Schaeff H Zimmermann H . Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Letermovir Coadministered With Cyclosporine A or Tacrolimus in Healthy Subjects. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev (2018) 7(1):9–21. 10.1002/cpdd.388

4.

Benotmane I Perrin P Caillard S . Letermovir vs Valganciclovir for Cytomegalovirus Prophylaxis After Kidney Transplant. JAMA (2023) 330(18):1803. 10.1001/jama.2023.18019

5.

Winstead RJ Kumar D Brown A Yakubu I Song C Thacker L et al Letermovir Prophylaxis in Solid Organ transplant-Assessing CMV Breakthrough and Tacrolimus Drug Interaction. Transpl Infect Dis Off J Transpl Soc (2021) 23(4):e13570. 10.1111/tid.13570

6.

Jorgenson MR Descourouez JL Saddler CM Smith JA Odorico JS Rice JP et al Real World Experience with Conversion from Valganciclovir to Letermovir for Cytomegalovirus Prophylaxis: Letermovir Reverses Leukopenia and Avoids Mycophenolate Dose Reduction. Clin Transpl (2023) 37(12):e15142. 10.1111/ctr.15142

7.

Hedvat J Choe JY Salerno DM Scheffert JL Kovac D Anamisis A et al Managing the Significant Drug-Drug Interaction Between Tacrolimus and Letermovir in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Clin Transpl (2021) 35(3):e14213. 10.1111/ctr.14213

8.

Menzel K Kothare P McCrea JB Chu X Kropeit D . Absorption, Metabolism, Distribution, and Excretion of Letermovir. Curr Drug Metab (2021) 22(10):784–94. 10.2174/1389200222666210223112826

9.

Limaye AP Budde K Humar A Vincenti F Kuypers DRJ Carroll RP et al Letermovir vs Valganciclovir for Prophylaxis of Cytomegalovirus in High-Risk Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA (2023) 330:33–42. 10.1001/jama.2023.9106

10.

Veit T Munker D Barton J Milger K Kauke T Meiser B et al Letermovir in Lung Transplant Recipients with Cytomegalovirus Infection: A Retrospective Observational Study. Am J Transpl (2021) 21(10):3449–55. 10.1111/ajt.16718

Summary

Keywords

cytomegalovirus, letermovir, drug interactions, kidney transplant, kidney function

Citation

Benotmane I, Schvartz B, Garrouste C, Runyo F, Boud’hors C, Flahaut G, Danthu C, Bertrand D and Caillard S (2025) Real-World Evaluation of Letermovir Use in Kidney Transplant Recipients: Drug Interactions, Safety, and Impact on Renal Function. Transpl. Int. 38:15371. doi: 10.3389/ti.2025.15371

Received

03 August 2025

Revised

19 November 2025

Accepted

24 November 2025

Published

04 December 2025

Volume

38 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Benotmane, Schvartz, Garrouste, Runyo, Boud’hors, Flahaut, Danthu, Bertrand and Caillard.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ilies Benotmane, Ilies.benotmane@chru-strasbourg.fr

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.