Abstract

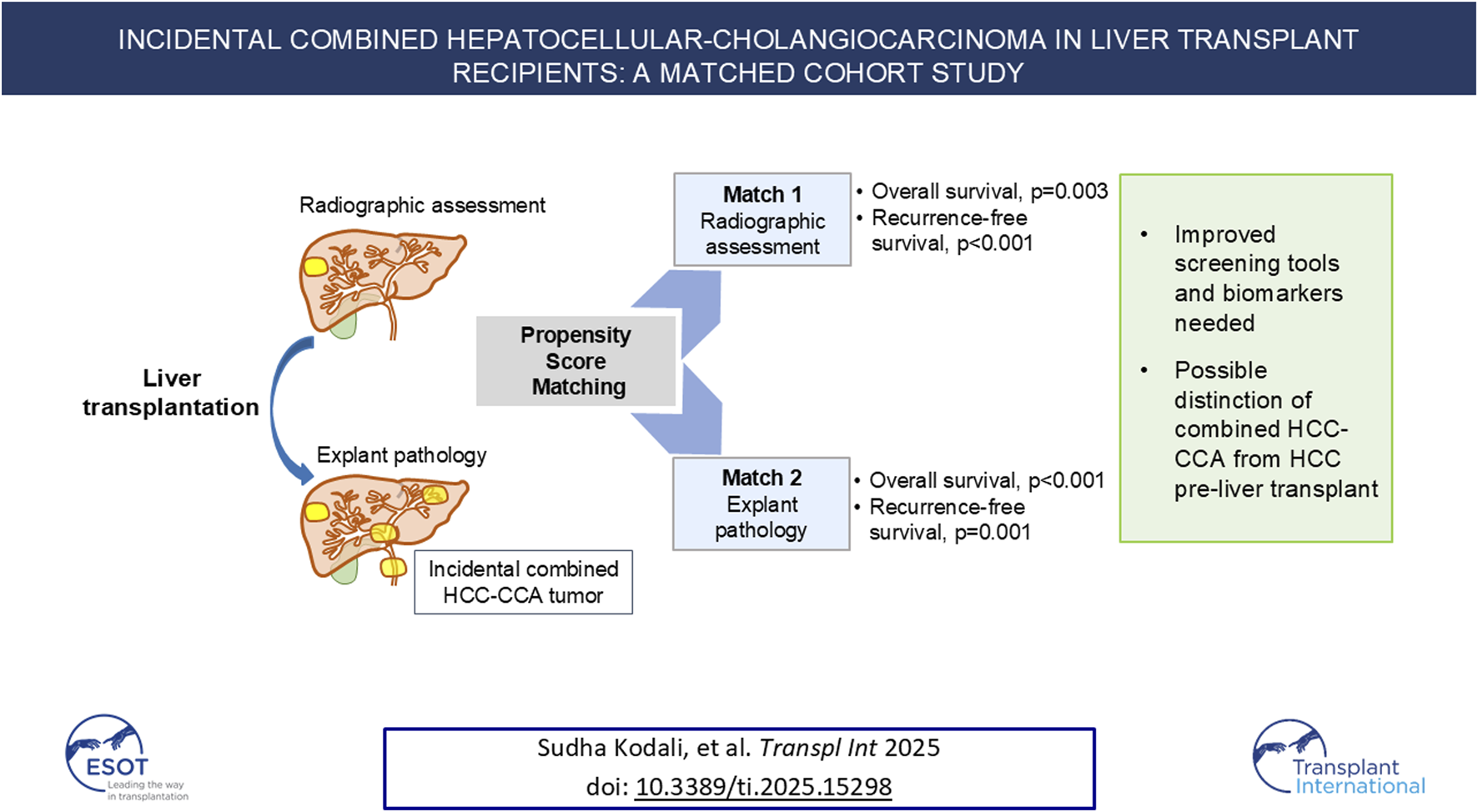

Mixed hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with cholangiocarcinoma (HCC-CCA) is an aggressive primary liver cancer and difficult to distinguish from HCC using non-invasive methods. Outcomes of patients incidentally diagnosed with HCC-CCA after LT relative to pure HCC with similar tumor burden were investigated. Medical records of patients undergoing LT (n = 1,898) for HCC (n = 493) from 6/2008–9/2023 were reviewed. Patients incidentally diagnosed with HCC-CCA were propensity matched to HCC patients undergoing LT. Independent analyses were performed using pre-LT (Match1; identifiable pre-LT) and explant pathology (Match2, more prognostic) characteristics. Incidental HCC-CCA occurred in 19 (3.9%) patients; all assumed to have HCC pre-LT and received HCC-directed neoadjuvant treatment. When matched on pre-LT characteristics (Match1, n = 57), more patients with HCC-CCA were outside Milan or University of California, San Francisco criteria on explant (p = 0.01). More patients with HCC-CCA underwent neoadjuvant microwave ablation (p = 0.02) compared to HCC Match2 (n = 45) but were otherwise similar demographically and clinically. Overall and recurrence-free survival were lower for HCC-CCA in Match1 (p = 0.003 and p < 0.001, respectively) and Match2 (p < 0.001 and p = 0.001, respectively). HCC-CCA has an aggressive phenotype with high recurrence after LT. Better screening tools and biomarkers are needed to distinguish HCC-CCA from HCC to ensure patients receive appropriate treatment and maximize post-LT outcomes.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Primary hepatic malignancies are increasing in incidence and are now the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1]. Combined or mixed hepatocellular carcinoma-cholangiocarcinoma (HCC-CCA), accounting for around 0.4%–14.2% of primary liver cancers, is rare and often misclassified as HCC pre-transplant with worse outcomes [2]. Studies indicate that HCC-CCA tumors are more aggressive than HCC tumors and are associated with poorer prognosis than either HCC and or CCA alone [2–5].

Unlike HCC, HCC-CCA has largely been considered a contraindication for liver transplantation (LT) due to the increased risk of post-transplant recurrence and poor outcomes [6]. LT does provide a survival benefit over resection in patients with mixed tumors [7–9], but that benefit has traditionally been outweighed by the need to pursue utility in deceased donor grafts allocation. Importantly, most HCC-CCA cases in LT recipients were considered to be HCC alone prior to transplantation due to the difficulty in distinguishing HCC-CCA from HCC radiologically [10–13]. Thus, incidental diagnosis seems to be the norm for patients with HCC-CCA undergoing LT.

Some reports indicate an increasing incidence of incidental HCC-CCA in LT recipients in recent years [8, 10]. It is important to determine optimal treatment regimens to provide the best medical care possible to patients with HCC-CCA. Given the rarity of this type of tumor and that LT is not standard-of-care, a detailed description of the trajectory of patients with HCC-CCA provides important information on clinical outcomes. The primary aim of this paper is to describe the outcomes of LT recipients presumed to have HCC alone pre-LT and received neoadjuvant treatment for HCC but found to have HCC-CCA on explant. The secondary aims were to compare pre-LT (representing clinical decision making) versus explant predictors and to examine the patterns of recurrence and treatment.

Materials and Methods

Medical records of 1,898 adult patients undergoing LT at a single, quaternary care institution between June 2008 and September 2023 were reviewed. Patients diagnosed with mixed HCC-CCA on explant were included in the primary analysis. All work was carried out with approval from the Houston Methodist Research Institute Institutional Review Board under protocol number Pro00000587 with a waiver of authorization. The center follows the guidance of the Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism.

A multidisciplinary tumor board reviewed the medical records of patients referred for LT who had a diagnosis of liver cancer and made clinical care recommendations, including systemic therapy and locoregional therapy (LRT). Patients with large, single tumors (>5 cm in diameter), multifocal lesions, or poorly differentiated tumors received combined neoadjuvant systemic therapy and LRT. Neoadjuvant treatment was HCC-directed, as all patients with HCC-CCA were believed to have HCC prior to undergoing LT. All patients in the study were appropriately treated and down staged with LRT. Microwave ablation, TACE, and TARE were the LRT modalities utilized. Decisions to place patients on the LT waitlist were made by a multidisciplinary transplant medical review board. While on the LT waitlist, patients underwent close monitoring, including cross-sectional imaging every 3 months to rule out disease progression.

Statistical Analysis

HCC-CCA recipients were matched with HCC alone recipients using a propensity score method of 1:3 (as 1 HCC-CCA case to 3 HCC cases), using a non-replacement, caliper width 0.2 approach. Propensity score matching allowed comparisons between patients with similar disease burden. Since the patients with HCC-CCA were determined at the time of liver explant, it was decided to perform 2 independent propensity score matches. Variables were chosen based on established prognostic factors in HCC. The first match utilized characteristics measurable pre-transplant that could inform clinical decision making and transplant candidate selection (“pre-LT match”): pre-transplant alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels and total radiologic tumor diameter. No imputation of missing variables was planned.

The second, independently performed propensity score match used features from explant pathology (“explant match”), which are frequently more prognostic than pre-transplant variables in HCC [14–16]. This match more reflects the actual pathologic risk of the lesions on explant. The propensity match was performed using a 1:3 ratio of 1 HCC-CCA to 3 HCC alone cases, again using the non-replacement, 0.2 caliper width approach. The scoring was based on pathologic total tumor diameter, tumor differentiation, and presence or absence of vascular invasion. No imputation of missing variables was planned.

Demographic and clinical data are reported as frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. Differences between patients with HCC-CCA and matched patients with HCC were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. Balance of the covariates used as the matching criteria was evaluated by the percent standardized bias. Overall all-cause patient and recurrence-free survival are presented by Kaplan-Meier curves. Differences in survival across groups were compared using the log-rank test. All analyses were performed on Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients With Mixed Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Cholangiocarcinoma

Of 493 patients having LT for HCC, 19 (3.9%) patients with incidentally diagnosed HCC-CCA underwent LT for HCC during the study period (Table 1). Recipients were predominantly male (15, 78.9%) and white (14, 73.7%). Most had viral disease etiology (Hepatitis C: 8 [42.1%]; Hepatitis B: 2 [10.5%]). All received a deceased donor LT. Median laboratory Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score at transplant was 17 (IQR, 9–29). These patients generally had low serum tumor markers: median alpha fetoprotein (AFP) was 7.1 (2.7–22.2) ng/mL at listing and was 5.2 (2.6–20.9) ng/mL at transplant. Median carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19-9) level measured soonest prior to LT was 34.0 (19.3–54.0) U/mL, and 11 (57.9%) patients had “normal” CA19-9 values (<37 U/mL). Only one patient (5.3%) had CA19-9 >100 U/mL.

TABLE 1

| Recipient Characteristics | Mixed tumor | HCC Pre-LT match | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 19 | N = 57 | ||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 65.2 (61.1, 69.5) | 62.0 (57.0, 67.0) | 0.12 |

| Sex, n (%) | | | 0.77 |

| Male | 4 (21.1) | 15 (26.3) | |

| Female | 15 (78.9) | 42 (73.7) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | | | 0.76 |

| White | 14 (73.7) | 39 (68.4) | |

| Black | 0 (0.0) | 4 (7.0) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (15.8) | 10 (17.5) | |

| Asian | 2 (10.5) | 4 (7.0) | |

| BMI at LT (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 29.6 (24.8, 33.9) | 27.3 (23.9, 32.7) | 0.64 |

| Laboratory MELD at transplant, median (IQR) | 17.0 (9.0, 29.0) | 13.0 (10.0, 19.0) | 0.57 |

| Underlying etiology of liver disease, n (%) | | | 0.19 |

| Hepatitis C | 8 (42.1) | 39 (68.4) | |

| Hepatitis B | 2 (10.5) | 3 (5.3) | |

| Alcohol-associated liver disease | 3 (15.8) | 7 (12.3) | |

| MASLD or cryptogenic cirrhosis | 5 (26.3) | 7 (12.3) | |

| Other | 1 (5.3) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Waiting time from listing (days), median (IQR) | 332.0 (148.0, 806.0) | 346.0 (190.0, 525.0) | 0.67 |

| Pre-transplant tumor markers | |||

| Last AFP prior to transplant (ng/mL), median (IQR) | 5.2 (2.6, 20.9) | 6.6 (3.6, 27.3) | 0.63 |

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio pre-LT, median (IQR) | 3.5 (2.0, 7.2) | 5.8 (2.7, 17.9) | 0.15 |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | |||

| Neoadjuvant therapy, n (%) | |||

| TACE | 11 (57.9) | 43 (75.4) | 0.16 |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 4 (21.1) | 13 (22.8) | 1.00 |

| Resection | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.5) | 1.00 |

| Sorafenib | 5 (26.3) | 14 (24.6) | 1.00 |

| Yttrium-90 | 2 (10.5) | 3 (5.3) | 0.59 |

| Microwave ablation | 3 (15.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.01 |

| Total number of LRT, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 0.09 |

| Pre-transplant radiographic tumor characteristics | |||

| Tumor burden classification, n (%) | | | 0.54 |

| Within Milan | 16 (84.2) | 45 (78.9) | |

| Outside Milan, within UCSF | 2 (10.5) | 4 (7.0) | |

| Outside UCSF | 1 (5.3) | 8 (14.0) | |

| Pathologic tumor characteristics | |||

| Tumor burden classification, n (%) | | | 0.01 |

| Within Milan | 7 (36.8) | 38 (66.7) | |

| Outside Milan, within UCSF | 6 (31.6) | 4 (7.0) | |

| Outside UCSF | 6 (31.6) | 15 (26.3) | |

| Tumor T stage, n (%) | | | 0.30 |

| T0 | 1 (5.3) | 1 (2.8) | |

| T1s | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| T1 | 4 (21.1) | 15 (41.7) | |

| T2 | 9 (47.4) | 17 (47.2) | |

| T3a | 2 (10.5) | 2 (5.6) | |

| T3b | 1 (5.3) | 1 (2.8) | |

| T4 | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Tumor N Stage, n (%) | | | 0.37 |

| N0 | 8 (42.1) | 21 (58.3) | |

| N1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.8) | |

| NX | 11 (57.9) | 14 (38.9) | |

| Microvascular invasion, n (%) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (5.6) | 0.60 |

| Total number of tumors (pathology), median (IQR) | 2.0 (2.0, 4.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 0.34 |

| Largest tumor diameter (cm), median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0, 3.8) | 2.5 (2.0, 3.1) | 0.20 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Tumor recurrence, n (%) | | | 0.001 |

| No | 10 (52.6) | 51 (89.5) | |

| Yes | 9 (47.4) | 6 (10.5) | |

| Patient status, n (%) | | | 0.003 |

| Deceased | 13 (68.4) | 16 (28.1) | |

| Alive | 6 (31.6) | 41 (71.9) | |

| Propensity score matching criteria | |||

| AFP at listing (ng/mL), median (IQR) | 7.1 (2.7, 22.2) | 7.9 (4.3, 32.9) | 0.22 |

| Total radiographic total tumor diameter at listing (cm), median (IQR) | 2.2 (1.3, 4.3) | 2.3 (1.2, 5.3) | 0.71 |

| Total number of tumors at last scan pre-LT, median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 0.80 |

Clinical characteristics of liver transplant recipients with mixed hepatocellular carcinoma-cholangiocarcinoma and propensity-matched patients with hepatocellular carcinoma only based on pre-transplant variables (“pre-LT match”).

Bold values denote statistical significance (p < 0.05).

AFP, alpha fetoprotein; BMI, body mass index; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IQR, interquartile range; LRT, locoregional therapies; LT, liver transplantation; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; UCSF, University of California, San Francisco.

Because the patients were thought to have HCC prior to LT based on imaging characteristics, they received neoadjuvant therapies directed at HCC. Most (n = 16, 84.2%) received some type of neoadjuvant therapy (Table 1). TACE was most frequently used (n = 11, 57.9%), followed by sorafenib (n = 5, 26.3%), and radiofrequency ablation (RFA, n = 4, 21.1%, including 1 patient who received both RFA and TACE). Three patients (15.8%) received microwave ablation and two (10.5%) received yttrium-90 (Y90) as neoadjuvant treatment. The 5 patients who received neoadjuvant sorafenib underwent treatment in 2015 or earlier and are included in the count of those who received TACE. Based on pre-LT radiographic measurements, most (n = 16, 84.2%) were within Milan criteria. Two patients (10.5%) were outside Milan but within University of California, San Francisco (USCF) criteria, and one patient (5.3%) was outside UCSF criteria (Table 1).

The median largest tumor size in the HCC-CCA cases was ∼3.0 (IQR, 2.0–3.8); most patients had multifocal disease. Based on pathology results, 7 (36.8%) patients were within Milan, 6 (31.6%) were outside Milan and within UCSF, and 6 (31.6%) were outside USCF criteria. Of the patients who were outside UCSF criteria on explant, 5 patients responded to LRT with tumor size stabilization or reduction. One patient was transplanted urgently and had only hepatic ultrasound pre-LT; thus, this case did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy or LRT.

Most patients had T2 tumors (9, 47.4%), based on pathologic findings in the explants (Table 1). One patient (5.3%) had nodal metastases. None of the patients had macrovascular invasion, and 2 (10.5%) patients were found to have microvascular invasion (Supplementary Table S2). Most patients had moderately (n = 9, 47.4%) or poorly (n = 9, 47.4%) differentiated tumors; only one (1.8%) patient had well-differentiated HCC-CCA.

Data on post-LT adjuvant therapy was available for 18 of 19 patients. Of those 18 patients, 13 received adjuvant therapy with most patients receiving gemcitabine- or capecitabine-based therapy (Supplementary Table S3). None of the patients had metastatic disease at transplant.

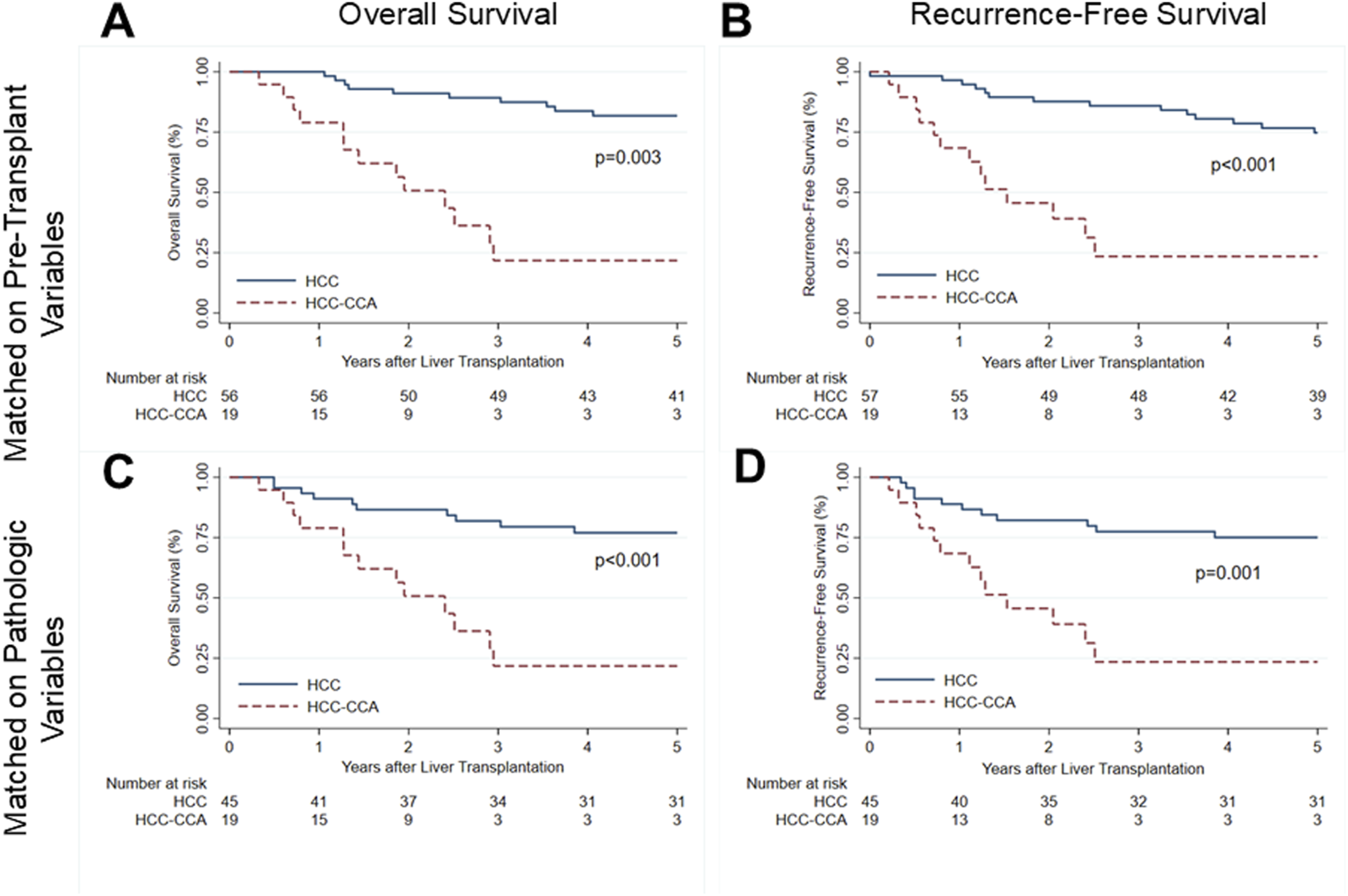

At a median post-transplant follow-up of 1.95 years, 13 (68.4%) of the 19 patients with HCC-CCA were deceased (Table 1). Nine (47.4%) patients ultimately died from metastatic adenocarcinoma, 2 (10.5%) from cardiac arrest, 1 (5.3%) from multi-system organ failure, and 1 (5.3%) from respiratory failure. Overall survival (OS) rates of patients with mixed tumors were 78.9% at 1 year and 23.8% at 3 and 5 years post-LT (Figure 1A). Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was 68.4% at 1 year and 26.8% at 3 and 5 years after transplant (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1

Survival after liver transplantation for patients with mixed hepatocellular carcinoma-cholangiocarcinoma (solid line) and propensity-matched patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (dashed line). (A) Overall patient survival and (B) recurrence-free survival for mixed tumor patients and patients with HCC matched on pre-transplant characteristics. (C) Overall patient survival and (D) recurrence-free survival for mixed tumor patients and HCC patients matched on explant pathology characteristics. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCC-CCA, mixed hepatocellular carcinoma-cholangiocarcinoma.

Pre-Liver Transplantation Matched Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patient Comparison

The pre-LT match included 57 patients with HCC matched to the 19 patients with HCC-CCA based on pre-transplant characteristics. No missing variables occurred in the match. Characteristics of the entire HCC cohort are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Demographically, patients with mixed tumor and HCC alone were similar, and they also had similar indications for LT (all p > 0.05; Table 1; Supplementary Table S2). There were also no differences in severity of illness: laboratory MELD (p = 0.57), listing MELD (p = 0.80), and medical condition at transplant (p = 1.00) were all statistically similar.

Serum tumor markers (AFP, neutrophil-to-leukocyte ratio) at the time of listing and prior to LT were also not significantly different between patients with HCC-CCA and matched patients with HCC (all p > 0.05) when matched on pre-LT features (Table 1). Radiographically, tumor number (p = 0.86) and total tumor diameter at listing (p = 0.71) were similar. Patients with HCC-CCA also received similar types of neoadjuvant therapy (all p > 0.05) apart from microwave ablation (MWA), which occurred more often in HCC-CCA (p = 0.01; Table 1). The number of locoregional therapy treatments were similar between groups (p = 0.70; Table 1). HCC T and N staging based on explant pathology was also similar between patients with HCC-CCA and pre-LT matched HCC alone (T stage, p = 0.30; N stage, p = 0.37; Table 1). Both groups also had similar pathologic estimated tumor necrosis (p = 0.40). Importantly, although pre-LT tumor burden was similar between groups, a significantly greater proportion of patients with HCC-CCA were found to be outside Milan and UCSF criteria on explant, indicative of the true biological disease burden (p = 0.01; Table 1).

Relative to matched patients with HCC, patients with HCC-CCA had significantly lower OS (log-rank: p = 0.003; Figure 1A) and RFS (log-rank: p < 0.001; Figure 1B). By Cox proportional hazards analysis, OS for patients with HCC-CCA had a hazard ratio (HR) of 6.47 (95% CI, 2.87–14.55; p < 0.001) relative to patients with HCC only matched on pre-LT features. Similarly, RFS rates were significantly inferior for patients with HCC-CCA (HR, 5.55; 95% CI, 2.58–11.97; p < 0.001).

Explant Pathology Matched Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patient Comparison

The second, independent propensity match using explant pathology features (“explant match”) included 45 patients with HCC matched to the core cohort of 19 patients with HCC-CCA. No missing variables occurred in the match. The patients with HCC-CCA had similar demographics as the patients with explant-matched HCC (all p > 0.05; Supplementary Table S4). Etiology of liver disease was not significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.62; Table 2), and they also had similar laboratory MELD scores at transplant (p = 0.58). AFP levels at listing and immediately prior to transplant were not statistically different between patients with HCC-CCA and patients with HCC (p = 0.07 and p = 0.75, respectively; Table 2). Patients with HCC-CCA were more likely to have received neoadjuvant MWA than patients with HCC matched on explant pathology features (15.8% vs. 0%; p = 0.02; Table 2).

TABLE 2

| Recipient Characteristics | Mixed Tumor | HCC Explant Match | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 19 | N = 45 | ||

| Laboratory MELD at transplant, median (IQR) | 17.0 (9.0, 29.0) | 13.0 (10.0, 25.0) | 0.58 |

| List MELD at txp, median (IQR) | 29.0 (26.0, 33.0) | 29.0 (27.0, 32.0) | 0.85 |

| Underlying etiology of liver disease, n (%) | | | 0.62 |

| Hepatitis C | 8 (42.1) | 27 (60.0) | |

| Hepatitis B | 2 (10.5) | 2 (4.4) | |

| Alcohol-associated liver disease | 3 (15.8) | 5 (11.1) | |

| MASLD or cryptogenic cirrhosis | 5 (26.3) | 8 (17.8) | |

| Other | 1 (5.3) | 3 (6.7) | |

| Waiting time from listing (days), median (IQR) | 332.0 (148.0, 806.0) | 364.0 (206.0, 571.0) | 0.98 |

| Pre-transplant tumor markers | |||

| AFP at listing (ng/mL), median (IQR) | 7.1 (2.7, 22.2) | 17.2 (4.8, 56.1) | 0.07 |

| Last AFP prior to transplant (ng/mL), median (IQR) | 5.2 (2.6, 20.9) | 7.6 (3.6, 25.1) | 0.75 |

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio pre-LT, median (IQR) | 3.5 (2.0, 7.2) | 4.4 (2.2, 9.2) | 0.59 |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | |||

| Neoadjuvant therapy, n (%) | |||

| TACE | 11 (57.9) | 33 (73.3) | 0.25 |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 4 (21.1) | 13 (28.9) | 0.76 |

| Resection | 0 (0.0) | 3 (6.7) | 0.55 |

| Sorafenib | 5 (26.3) | 17 (37.8) | 0.57 |

| Yttrium-90 | 2 (10.5) | 5 (11.1) | 1.00 |

| Microwave ablation | 3 (15.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.02 |

| Any neoadjuvant therapy, n (%) | 16 (84.2) | 41 (91.1) | 0.41 |

| Total number of LRT, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 0.78 |

| Pre-transplant radiographic tumor characteristics | |||

| Tumor burden classification, n (%) | | | 0.11 |

| Within Milan | 16 (84.2) | 25 (55.6) | |

| Outside Milan, within UCSF | 2 (10.5) | 11 (24.4) | |

| Outside UCSF | 1 (5.3) | 9 (20.0) | |

| Total radiographic total tumor diameter at listing (cm), median (IQR) | 2.2 (1.3, 4.3) | 3.5 (2.1, 5.3) | 0.09 |

| Total number of tumors at listing, median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 0.84 |

| Pathologic tumor characteristics | |||

| Tumor burden classification, n (%) | | | 0.44 |

| Within Milan | 7 (36.8) | 17 (37.8) | |

| Outside Milan, within UCSF | 6 (31.6) | 8 (17.8) | |

| Outside UCSF | 6 (31.6) | 20 (44.4) | |

| HCC necrosis estimate (%), median (IQR) | 35.0 (10.0, 80.0) | 65.0 (20.0, 95.0) | 0.32 |

| Tumor location, n (%) | | | 0.26 |

| Right lobe | 8 (42.1) | 27 (60.0) | |

| Left lobe | 3 (15.8) | 4 (8.9) | |

| Bilobar | 7 (36.8) | 14 (31.1) | |

| Other | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Tumor T stage, n (%) | | | 0.49 |

| T0 | 1 (5.3) | 1 (2.2) | |

| T1s | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| T1 | 4 (21.1) | 14 (31.1) | |

| T2 | 9 (47.4) | 20 (44.4) | |

| T3a | 2 (10.5) | 8 (17.8) | |

| T3b | 1 (5.3) | 1 (2.2) | |

| T4 | 1 (5.3) | 1 (2.2) | |

| Tumor N Stage, n (%) | | | 0.36 |

| N0 | 8 (42.1) | 27 (60.0) | |

| N1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | |

| NX | 11 (57.9) | 17 (37.8) | |

| Microvascular invasion, n (%) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (2.2) | 0.21 |

| Total number of tumors (pathology), median (IQR) | 2.0 (2.0, 4.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.0) | 0.87 |

| Largest tumor diameter (cm), median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0, 3.8) | 3.5 (2.7, 4.7) | 0.08 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Tumor recurrence, n (%) | | | 0.01 |

| No | 10 (52.6) | 38 (84.4) | |

| Yes | 9 (47.4) | 7 (15.6) | |

| Patient status, n (%) | | | 0.005 |

| Deceased | 13 (68.4) | 13 (28.9) | |

| Alive | 6 (31.6) | 32 (71.1) | |

| Total intraoperative PRBC (units), median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0, 10.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 6.0) | 0.99 |

| Propensity score matching criteria | |||

| Pathologic total tumor diameter (cm), median (IQR) | 5.6 (3.5, 7.3) | 6.0 (4.1, 11.0) | 0.83 |

| Pathologic differentiation, n (%) | | | 0.68 |

| Well | 1 (5.3) | 3 (6.7) | |

| Moderate | 9 (47.4) | 27 (60.0) | |

| Poor | 9 (47.4) | 15 (33.3) | |

| Any vascular invasion, n (%) | | | 0.21 |

| No | 17 (89.5) | 44 (97.8) | |

| Yes | 2 (10.5) | 1 (2.2) | |

Clinical characteristics of liver transplant recipients with mixed hepatocellular carcinoma-cholangiocarcinoma and propensity-matched patients with hepatocellular carcinoma only based on explant pathology variables (“explant match”).

Bold values denote statistical significance (p < 0.05).

AFP, alpha fetoprotein; BMI, body mass index; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IQR, interquartile range; LRT, locoregional therapies; LT, liver transplantation; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; UCSF, University of California, San Francisco.

Disease burden was similar between HCC-CCA and HCC alone in the “explant match” group. The proportion of patients within or outside Milan or USCF criteria were similar between groups (p = 0.44). Pre-transplant radiographic lesion number (p = 0.84) and total tumor diameter (p = 0.09) were not statistically different. Total tumor number (p = 0.87) and tumor diameter (p = 0.08) on explant were also statistically comparable. T (p = 0.49) and N (p = 0.36) staging were similar between groups (Table 2). Microvascular invasion rates were similar among HCC-CCA (10.5%) and HCC alone in the “explant match” group (2.2%; p = 0.21).

Mixed tumor cases had significantly lower OS (log-rank: p < 0.001; Figure 1C) and RFS (log-rank: p = 0.001; Figure 1D) rates than those with HCC alone matched on explant features. In univariable Cox proportional hazards analysis, both OS (HR, 4.67; 95% CI, 2.07–10.53; p = 0.0003) and RFS (HR, 3.65; 95% CI, 1.70–7.82; p = 0.001) were significantly inferior for patients with HCC-CCA.

Discussion

Patients with HCC-CCA had significantly worse OS and RFS than HCC, despite similar clinical features. This reflects the aggressive biology and challenges of pre-LT diagnosis. These comparisons identified patients with HCC with similar features that inform pre-LT clinical decision making and that approximate actual pathologic risk, respectively. Unfortunately, the mixed tumor patients had low AFP and CA19-9 levels and were radiographically similar to patients with HCC alone, making correct pre-LT diagnosis difficult. Like many other studies, the patients with mixed tumor in this cohort were originally diagnosed with HCC and thus received HCC-directed neoadjuvant therapy. It is likely that the CCA component of the mixed HCC-CCA lesions did not receive appropriate neoadjuvant systemic treatment, such as standard chemotherapy regimens for CCA. All patients with intrahepatic CCA considered for LT at our institution receive neoadjuvant gemcitabine and cisplatin as bridging and downstaging therapy, which is also used to inform patient selection [17]. It was not possible to follow the standard protocol in patients who were determined to have HCC-CCA only at the time of examination of the liver explant. These patients did receive CCA-focused adjuvant therapy. Due to the small sample size, we are unable to make conclusions regarding the efficacy of one adjuvant therapy over another, and the adjuvant regimens remain hypothesis-generating only.

The propensity match analysis provides insight into the clinical presentation and biology of HCC-CCA compared to HCC with similar pre-LT (Match 1) and post-LT (Match 2) characteristics. Matching on a small subset of prognostic variables allows us to better understand differences in mixed tumors and HCC when controlling for tumor burden. In both analyses, patients with HCC-CCA were more likely to have received neoadjuvant MWA. MWA has been shown to be an effective treatment in both HCC [18] and iCCA [19], and single-center studies have demonstrated its efficacy as a bridging [20, 21] and downstaging therapy [22]. Thus, it is unlikely that the use of MWA significantly affected outcomes. Patients matched on pre-LT characteristics (Match 1) were more likely to be outside Milan criteria on explant, highlighting the difficulty of radiologic staging in biologically aggressive tumors. This result highlights the difficulty of estimating tumor burden pre-LT in patients whose tumors have aggressive biology, such as HCC-CCA. It is interesting that 9 of the HCC-CCA patients with tumors inside Milan criteria radiologically pre-LT were outside Milan on explant pathology. Only 2 patients were outside Milan criteria due to lymphovascular invasion, which is very difficult to detect radiologically.

The 3- and 5-year OS rates for the cohort of 19 patients with HCC-CCA described here were much lower than other papers have reported (Table 3). Most patients with mixed tumors were thought to be within Milan criteria pre-LT (16, 84.2%), demonstrating that poor outcomes can occur even with a small tumor burden. Other papers have also shown that patients with HCC-CCA have worse outcomes than matched patients with HCC alone [13, 23–25], although some centers have reported similar survival rates [8, 9, 26, 27]. The OS rates reported here are also much lower than what our own center has demonstrated for patients with large HCC tumor burden (beyond UCSF criteria) [28], and for patients with intrahepatic CCA [17]. Penzkofer and colleagues noted that outcomes seemed to be more strongly associated with the CCA component of the mixed tumors [11]; our data also support this conclusion.

TABLE 3

| Paper | Year | n | Data source | Dates | 1y OS (%) | 3y OS (%) | 5y OS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present study | | 19 | Texas, US (single center) | 2008–2022 | 78.9 | 23.8 | 23.8 |

| Panjala et al. | 2010 | 12 | Florida, US (single center) | 1998–2008 | 79 | 66 | 16 |

| Groeschl et al. | 2013 | 19 | SEER database (US) | 1973–2008 | 89 | 48 | |

| Sapisochin et al. | 2014 | 15 | Spain (multicenter) | 2000–2010 | 93 | 78 | 78 |

| Vilchez et al. | 2016 | 94 | UNOS database | 1994–2013 | 82 | 47 | 40 |

| Jung et al. | 2017 | 32 | Seoul, South Korea (single center) | 2005–2014 | 84.4 | 73.1 | 65.8 |

| Antwi et al. | 2018 | 19 | Florida, US (single center) | 2001–2016 | 84 | 74 | |

| Lunsford et al. | 2018 | 12 | California, US (single center) | 1984–2015 | 75 | 54 | 42 |

| Li et al. | 2019 | 301 | Meta-analysis | 2000–2018 | | | 41 |

| Spolverato et al. | 2019 | 220 | National cancer database | 2004–2015 | | | 52.6 |

| Dageforde et al. | 2021 | 99 | US consortium (12 centers) | 2009–2017 | 89.1a | 77.1a | 70.1a |

| Jaradat et al. | 2021 | 19 | Germany, Turkey, Jordan (multi-center) | 2001–2018 | 57.1 | 38.1 | |

| Brandão et al. | 2022 | 7 | Brazil (single center) | 1997–2019 | 85.7 | | 54.1 |

| Chen et al. | 2022 | 60 | SEER database (US) | 2004–2015 | 86.7 | 68.3 | 56.6 |

| Anilir et al. | 2023 | 17 | Turkey (single center) | 2004–2019 | 80.2 | 57.3 | 66.7 |

| Garcia-Moreno et al. | 2023 | 6 | Spain (single center) | 2006–2019 | 83.3 | 66.7 | 66.7 |

| Mi et al. | 2023 | 49 | SEER database (US) | 2000–2018 | 86.2 | 72.4 | 60.3 |

| Penzkofer et al. | 2023 | 6 | Germany (single center) | 2008–2020 | 100 | 100 | 80 |

| Kim et al. | 2023 | 111 | Korea (multicenter) | 2000–2018 | 84.4 | 63.8 | |

Summary of survival outcomes of literature reports of patients undergoing liver transplantation for combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma.

Patients within Milan criteria.

This study highlights the need for unique biomarkers, whether blood, tissue, or imaging, to distinguish HCC from HCC-CCA. Other studies of LT recipients have shown that CCA-specific biomarkers like CA19-9 were similar between patients with pure HCC and patients with mixed tumors [13]. Given that patients with mixed tumors have reduced expected post-LT survival, better methods for diagnosing HCC-CCA pre-LT are needed, particularly as the number of patients undergoing LT for oncologic indications increases. Patients whose lesions are identified as liver imaging reporting and data system (LIRADS)-M, presumed to have likely or definite malignancy, or imaging characteristics not typical of HCC, should undergo image-guided biopsy for definitive diagnosis. If a patient is confirmed to have HCC-CCA, centers should obtain genetic profiling/next-generation sequencing data to optimize tailoring treatment. Such genomic data can help guide physicians in selecting neoadjuvant systemic options that will treat both components (hepatocellular and adenocarcinoma) of the cancer. Given poor outcomes and high rates of recurrence, institution-based protocols are necessary for treating these aggressive cancers, considering the dearth of data in post-transplant outcomes in patients with HCC-CCA.

This study is limited by its retrospective nature and because it only incorporates patients from a single center. Additionally, very few patients underwent LT for HCC-CCA during the study period, limiting the sample size of this cohort, particularly at longer follow-up (>3 years post-LT) when many patients had died. Thus, the small number of patients could reduce the confidence in long-term follow up outcomes. Although our institution is in a region with high racial and ethnic diversity, the results presented here may not accurately reflect the experiences at other centers. There might be residual confounding arising from unmeasured patients’ attributes. Despite these limitations, this study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this manuscript presents the largest propensity score matching analysis of patients undergoing LT for HCC-CCA vs. HCC using multiple variables to select patients with similar disease burden. Thus, the conclusions drawn here provide important insight into the surgical treatment of patients with HCC-CCA. Another major strength of this cohort is the diverse patient population at our center. Although most patients with HCC-CCA were non-Hispanic White, this work still provides an accurate representation of the incidence of HCC-CCA in a diverse transplant population.

This manuscript provides a propensity-score matched comparison utilizing granular center medical records of patients receiving LT from deceased donors for HCC where incidental HCC-CCA occurred. Although LT can offer superior OS relative to resection [7, 9, 11], the study showed that survival is still much lower for patients with HCC-CCA than for HCC, the most common oncologic indication for LT. Given that most patients with HCC-CCA are diagnosed incidentally after transplant and are associated with inferior outcomes, allocation policy may need to weigh whether LT for HCC-CCA is justified without better selection tools and treatment options. Accurate pre-LT diagnosis may have allowed patients with HCC-CCA to receive adequate neoadjuvant treatment for the CCA component of the tumor, potentially improving outcomes. Better screening techniques are needed to identify patients with these rare tumors pre-transplant to ensure they receive the most appropriate treatment possible. Liquid biopsy and next-generation sequencing show promise in helping to accurately distinguish HCC-CCA from HCC [29]. Given the improved survival after LT for HCC-CCA relative to resection, increasing utilization of machine perfusion [30] and extended criteria donor grafts [31–34] may allow greater expansion of LT to well-selected patients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: Individual privacy is a concern when reporting on rare conditions. Therefore, the data are not available to be released. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to rmghobrial@houstonmethodist.org.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Houston Methodist Research Institute Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because the study was minimal risk. Informed consent was not practicable because some of the patients had died. The study uses only secondary data analysis.

Author contributions

SK – conception or design of the work; acquisition and interpretation of data; preparation of the manuscript; review and final approval of the manuscript. AC and AE – acquisition of data; interpretation of data; review and final approval of the manuscript. DV and MA interpretation of data; review and final approval of the manuscript. KP – conception or design of the work; acquisition and analysis of data; interpretation of data; review and final approval of the manuscript. EB – conception or design of the work; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; preparation of the manuscript; review and final approval of the manuscript. EG, DN, and SX – analysis and interpretation of data; review and final approval of the manuscript. LM – acquisition and interpretation of data; preparation of the manuscript; review and final approval of the manuscript. MS, SD, TB, M-JP, MH, CS, YL, KH, AK, AS, and AG – interpretation of data; review and final approval of the manuscript. RG – conception or design of the work; interpretation of data; review and final approval of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ti.2025.15298/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCC-CCA, mixed hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma; LT, liver transplantation.

References

1.

BrayFFerlayJSoerjomataramISiegelRLTorreLAJemalA. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2018) 68:394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492

2.

SchizasDMastorakiARoutsiEPapapanouMTsapralisDVassiliuPet alCombined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: An Update on Epidemiology, Classification, Diagnosis and Management. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int (2020) 19:515–23. 10.1016/j.hbpd.2020.07.004

3.

SpolveratoGBaganteFTsilimigrasDEjazACloydJPawlikTM. Management and Outcomes Among Patients with Mixed Hepatocholangiocellular Carcinoma: A Population-Based Analysis. J Surg Oncol (2019) 119:278–87. 10.1002/jso.25331

4.

ChenPDChenLJChangYJChangYJ. Long-Term Survival of Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: A Nationwide Study. Oncologist (2021) 26:e1774–e1785. 10.1002/onco.13893

5.

AmoryBGoumardCLaurentALangellaSCherquiDSalameEet alCombined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma Compared to Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Different Survival, Similar Recurrence: Report of a Large Study on Repurposed Databases with Propensity Score Matching. Surgery (2024) 175:413–23. 10.1016/j.surg.2023.09.040

6.

SapisochinGJavleMLerutJOhtsukaMGhobrialMHibiTet alLiver Transplantation for Cholangiocarcinoma and Mixed Hepatocellular Cholangiocarcinoma: Working Group Report from the ILTS Transplant Oncology Consensus Conference. Transplantation (2020) 104:1125–30. 10.1097/tp.0000000000003212

7.

MiSHouZQiuGJinZXieQHuangJ. Liver Transplantation Versus Resection for Patients with Combined Hepatocellular Cholangiocarcinoma: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Heliyon (2023) 9:e20945. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20945

8.

ChenXYSunSQLuYWWangZYShiXLChenXJet alPromising Role of Liver Transplantation in Patients with Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Ann Transl Med (2022) 10:21. 10.21037/atm-21-5391

9.

DagefordeLAVachharajaniNTabrizianPAgopianVHalazunKMaynardEet alMulti-Center Analysis of Liver Transplantation for Combined Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Cholangiocarcinoma Liver Tumors. J Am Coll Surg (2021) 232:361–71. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.11.017

10.

De MartinERayarMGolseNDupeuxMGelliMGnemmiVet alAnalysis of Liver Resection Versus Liver Transplantation on Outcome of Small Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma in the Setting of Cirrhosis. Liver Transpl (2020) 26:785–98. 10.1002/lt.25737

11.

PenzkoferLGrögerLKHoppe-LotichiusMBaumgartJHeinrichSMittlerJet alMixed Hepatocellular Cholangiocarcinoma: A Comparison of Survival Between Mixed Tumors, Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Hepatocellular Carcinoma from a Single Center. Cancers (Basel) (2023) 15:639. 10.3390/cancers15030639

12.

Garcia-MorenoVJusto-AlonsoIFernandez-FernandezCRivas-DuarteCAranda-RomeroBLoinaz-SegurolaCet alLong-Term Follow-Up of Liver Transplantation in Incidental Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Mixed Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma. Cir Esp Engl Ed (2023) 101:624–31. 10.1016/j.cireng.2023.04.010

13.

AnilirEOralASahinTTurkerFYuzerYTokatY. Incidental Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma in Liver Transplant Patients: Does It Have a Worse Prognosis?Hepatol Forum (2023) 4:97–102. 10.14744/hf.2022.2022.0037

14.

MehtaNHeimbachJHarnoisDMSapisochinGDodgeJLLeeDet alValidation of a Risk Estimation of Tumor Recurrence After Transplant (RETREAT) Score for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence After Liver Transplant. JAMA Oncol (2017) 3:493–500. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5116

15.

Al-AmeriAYuXBZhengSS. Predictors of Post-Recurrence Survival in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Following Liver Transplantation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transplant Rev (2022) 36:10. 10.1016/j.trre.2021.100676

16.

SotiropoulosGCMolmentiEPLöschCBeckebaumSBroelschCELangH. Meta-Analysis of Tumor Recurrence After Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Based on 1,198 Cases. Eur J Med Res (2007) 12:527–34.

17.

McMillanRRJavleMKodaliSSahariaAMobleyCHeyneKet alSurvival Following Liver Transplantation for Locally Advanced, Unresectable Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Transpl (2022) 22:823–32. 10.1111/ajt.16906

18.

CuiRYuJKuangMDuanFLiangP. Microwave Ablation Versus Other Interventions for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Cancer Res Ther (2020) 16:379–86. 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_403_19

19.

SongMLiJLiYZhangCSigdelMHouRet alEfficacy of Microwave Ablation for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Quant Imaging Med Surg (2025) 15:760–9. 10.21037/qims-24-607

20.

CouillardABKnottEAZlevorAMMezrichJDCristescuMMAgarwalPet alMicrowave Ablation as Bridging to Liver Transplant for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Single-Center Retrospective Analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol (2022) 33:1045–53. 10.1016/j.jvir.2022.05.019

21.

SomAReidNJDiCapuaJCochranRLAnTUppotRet alMicrowave Ablation as Bridging Therapy for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Awaiting Liver Transplant: A Single Center Experience. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol (2021) 44:1749–54. 10.1007/s00270-021-02873-7

22.

FrondaMSusannaEDoriguzzi BreattaAGazzeraCPatronoDPiccioneFet alCombined Transarterial Chemoembolization and Thermal Ablation in Candidates to Liver Transplantation with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Pathological Findings and Post-Transplant Outcome. Radiol Med (2024) 129:1086–97. 10.1007/s11547-024-01830-x

23.

LunsfordKECourtCSeok LeeYLuDSNainiBVHarlander-LockeMPet alPropensity-Matched Analysis of Patients with Mixed Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma and Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl (2018) 24:1384–97. 10.1002/lt.25058

24.

JaradatDBagiasGLorfTTokatYObedAOezcelikA. Liver Transplantation for Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: Outcomes and Prognostic Factors for Mortality. A Multicenter Analysis. Clin Transpl (2021) 35:e14094. 10.1111/ctr.14094

25.

KimJJooDJHwangSLeeJMRyuJHNahYWet alLiver Transplantation for Combined Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Cholangiocarcinoma: A Multicenter Study. World J Gastrointest Surg (2023) 15:1340–53. 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i7.1340

26.

BrandãoABMRodriguezSFleckAMJr.MarroniCAWagnerMBHörbeAet alPropensity-Matched Analysis of Patients with Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma or Mixed Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma and Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing a Liver Transplant. World J Clin Oncol (2022) 13:688–701. 10.5306/wjco.v13.i8.688

27.

SapisochinGFidelmanNRobertsJPYaoFY. Mixed Hepatocellular Cholangiocarcinoma and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma in Patients Undergoing Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Transpl (2011) 17:934–42. 10.1002/lt.22307

28.

VictorDW3rdMonsourHPJr.BoktourMLunsfordKBaloghJGravissEAet alOutcomes of Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Beyond the University of California San Francisco Criteria: A Single-Center Experience. Transplantation (2020) 104:113–21. 10.1097/tp.0000000000002835

29.

BeaufrèreACalderaroJParadisV. Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: An Update. J Hepatol (2021) 74:1212–24. 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.01.035

30.

GhinolfiDRrekaEPezzatiDFilipponiFDe SimoneP. Perfusion Machines and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Good Match Between a Marginal Organ and an Advanced Disease?Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol (2017) 2:87. 10.21037/tgh.2017.10.01

31.

NutuAJustoIMarcacuzcoACasoÓManriqueACalvoJet alLiver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using Grafts from Uncontrolled Circulatory Death Donation. Sci Rep (2021) 11:13520. 10.1038/s41598-021-92976-5

32.

CusumanoCDe CarlisLCentonzeLLesourdRLevi SandriGBLauterioAet alAdvanced Donor Age Does Not Increase Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence After Liver Transplantation: A Retrospective Two-Centre Analysis Using Competing Risk Analysis. Transpl Int (2021) 34:1948–58. 10.1111/tri.13950

33.

LozanovskiVJKerrLTBKhajehEGhamarnejadOPfeiffenbergerJHoffmannKet alLiver Grafts with Major Extended Donor Criteria May Expand the Organ Pool for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Clin Med (2019) 8:1692. 10.3390/jcm8101692

34.

CroomeKPLeeDDBurnsJMMustoKPazDNguyenJHet alThe Use of Donation After Cardiac Death Allografts Does Not Increase Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Am J Transpl (2015) 15:2704–11. 10.1111/ajt.13306

Summary

Keywords

hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, liver transplantation, transplant oncology, liver neoplasms

Citation

Kodali S, Connor AA, Victor DW III, Abdelrahim M, Elaileh A, Patel K, Brombosz EW, Graviss EA, Nguyen DT, Xu S, Moore LW, Schwartz MR, Dhingra S, Basra T, Jones-Pauley MR, Noureddin M, Mobley CM, Hobeika MJ, Simon CJ, Lee Cheah Y, Heyne K, Kaseb AO, Saharia A, Gaber AO and Ghobrial RM (2026) Incidental Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma in Liver Transplant Recipients: A Matched Cohort Study. Transpl. Int. 38:15298. doi: 10.3389/ti.2025.15298

Received

21 July 2025

Revised

19 October 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

28 January 2026

Volume

38 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Kodali, Connor, Victor, Abdelrahim, Elaileh, Patel, Brombosz, Graviss, Nguyen, Xu, Moore, Schwartz, Dhingra, Basra, Jones-Pauley, Noureddin, Mobley, Hobeika, Simon, Lee Cheah, Heyne, Kaseb, Saharia, Gaber and Ghobrial.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: R. Mark Ghobrial, rmghobrial@houstonmethodist.org

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.