Abstract

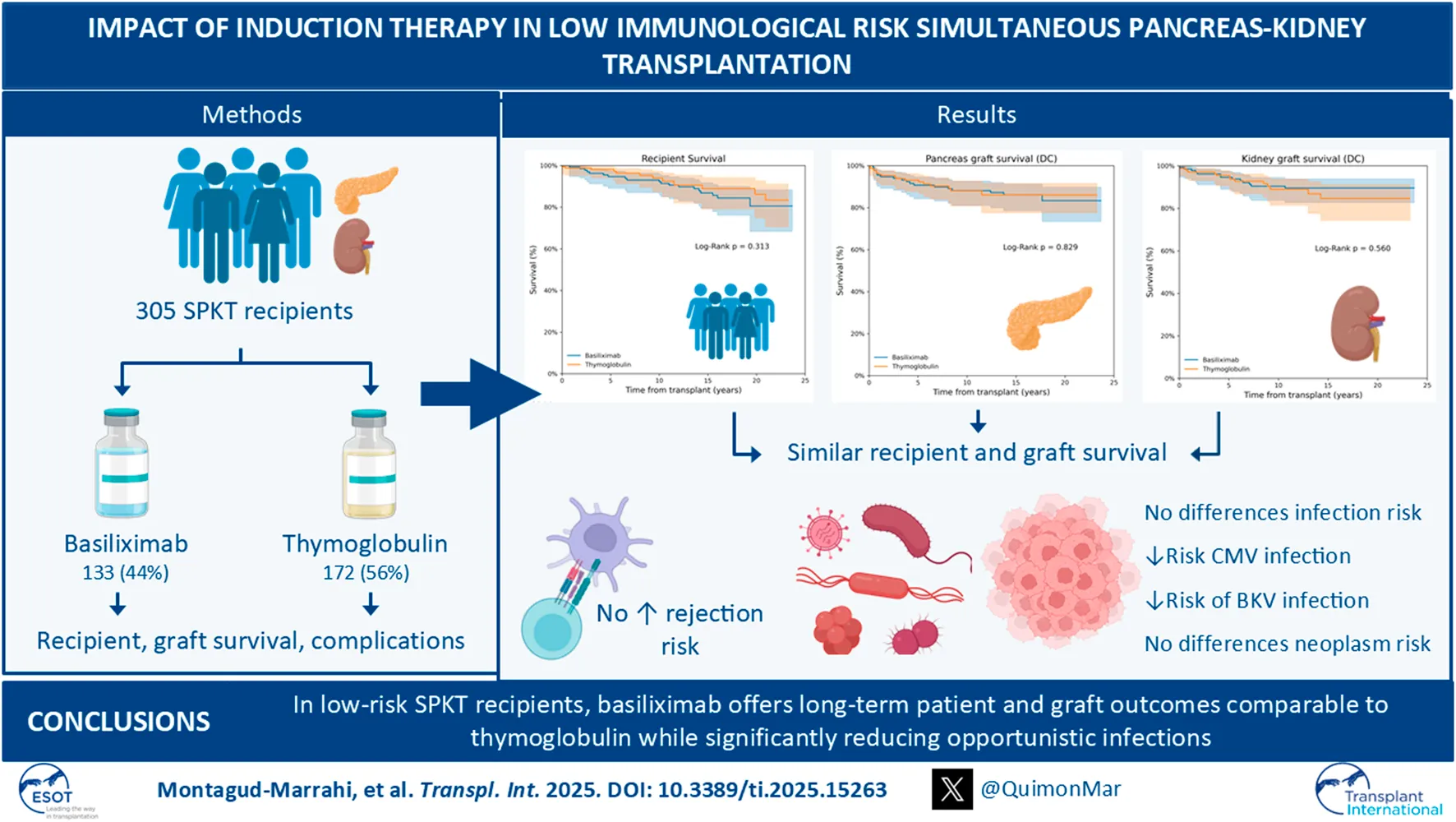

T-cell depleting agents and IL-2 receptor blockers are the most common induction therapies in simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation (SPKT), but the optimal choice remains debated. Here, we perform a retrospective, single-center study with SPKT recipients from 2000 to 2023. Basiliximab was used between 2008 and 2013, and thymoglobulin in other periods. Patients with prior transplants, calculated PRA >20%, pre-SPKT Donor-Specific Antibodies or graft primary non-function because technical reasons, were excluded. An Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW) was performed to adjust for confounding variables. 305 SPKT recipients were included, of which 172 (56%) received thymoglobulin and 133 (44%) basiliximab. Recipient (86% vs. 80%), pancreas (86% vs. 83%) and kidney (84% vs. 89%) death-censored graft survival at 20 years were comparable between groups. Basiliximab was not associated with an increased risk of patient death [HR 1.47 (0.69–3.14), P = 0.32], pancreas [HR 1.08 (0.55–2.10), P = 0.83] or kidney graft failure [HR 0.80 (0.38–1.70), P = 0.56] compared to thymoglobulin. Basiliximab did not significantly increase the risk of pancreas [OR 1.49 (0.84–2.63), P = 0.37] or kidney graft rejection [OR 1.31 (0.54–3.15), P = 0.20]. However, it was associated with significantly lower risk of CMV [OR 0.41 (0.23–0.72), P = 0.002] and BK virus infections [OR 0.31 (0.12–0.80), P = 0.02]. No significant difference was found in new-onset malignancy incidence. These results were maintained even after IPTW adjustment. In SPKT recipients with low immunological risk, basiliximab provides comparable long-term patient and graft outcomes to thymoglobulin while reducing the incidence of opportunistic infections.

Introduction

Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation (SPKT) has proven to be an effective therapy for patients with End-Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD) and insulin-dependent Diabetes Mellitus (DM), reducing the incidence of major cardiovascular events while improving patient survival and quality of life [1–5].

Despite significant advances in immunosuppressive therapy in recent years, allograft rejection remains one of the most common causes of graft loss, especially after 1 year post-transplant [5–7]. Immunosuppressive regimen for SPKT includes induction therapy, typically with either a T-cell depleting agent (e.g., thymoglobulin) or an IL-2 receptor blocker (e.g., basiliximab) administered in the immediate post-transplant period, followed by maintenance therapy, which usually consists of a combination of steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and an antiproliferative agent (such as mycophenolate or mTOR inhibitors) [8]. Most transplant centers use T-cell depleting agents for SPKT as induction therapy, regardless of the recipient’s immunological risk prior to transplantation [9, 10]. However, evidence comparing SPKT outcomes between T-cell depleting agents and basiliximab is controversial, particularly in patients with low immunological risk [8–10]. Identifying the most appropriate induction therapy for SPKT recipients is increasingly important, as T-cell depleting agents have been linked to higher rates of opportunistic infections and de novo malignancies, negatively impacting on recipient survival [10–12].

In the present study we compare post-transplant outcomes in SPKT recipients receiving either thymoglobulin or basiliximab as induction therapy. Specifically, we analyze patient and graft survival, rejection rates, incidence of infections, and the occurrence of de novo malignancies following transplantation.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

We conducted a longitudinal retrospective single center study including all SPKT performed at Hospital Clínic Barcelona from January 1st, 2000 until December 31st, 2023 (n = 385). Patients with ≥1 previous transplant of any type (n = 19), pre-transplant calculated Panel Reactive Antibody (cPRA) >20% and/or Donor Specific Antibodies (DSAs) (n = 54), and those with a kidney or pancreas graft primary non-function for technical reasons (n = 7) were excluded. In total, 305 SPKT recipients were included.

According to our immunology laboratory, a bead in the Single Antigen assay was considered positive when the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was ≥1,000. However, this threshold was subject to minor patient-specific adjustments based on the background MFI observed in non–donor-specific beads, which could result in a slightly higher or lower effective cut-off.

Data was collected until 31st December 2024. The clinical and research activities being reported were consistent with the Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (HCB/2025/0613).

Immunosuppression

Induction immunosuppression therapy was used in all patients, with two doses of basiliximab of 20 mg at day 0 and at day +4 after surgery between January 2008 until July 2013. Before January 2008, and after July 2013, rabbit anti-human lymphocytes polyclonal antibodies (either Thymoglobulin® 1.25 mg/kg/day or ATG® 2.5 mg/kg/day, for 4 consecutive days) was administered as induction therapy. The first dose was administered intraoperatively, and the subsequent three doses on consecutive days following surgery. Dosage was adjusted according to leukocyte and platelet counts: it was reduced by 50% if the leukocyte count was <3.000/mL and/or the platelet count was <75,000/mL. If the leukocyte count fell below 1.500/mL and/or the platelet count below 50.000/mL, the dose was postponed (not discontinued) until the following day to try to reach a total cumulative dose of 5 mg/kg (10 mg/kg for ATG).

Maintenance immunosuppression protocol was based on triple therapy with calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine A until 2005, and thereafter tacrolimus), mycophenolate or mTOR inhibitors, and steroids (methylprednisolone in the immediate post-transplant period, followed by oral prednisone). The first dose of the calcineurin inhibitor was administered immediately before surgery. Administration was not postponed in cases of kidney Delayed Graft Function (DGF), and dosage adjustments were made solely based on trough levels. Therefore, all patients received the same regimen regardless of kidney DGF occurrence and induction therapy.

Anticoagulation

Anticoagulation included subcutaneous enoxaparin 20 mg bid starting 8 h post-surgery and was maintained until patient discharge (in the absence of thrombotic/hemorrhagic complications), and acetylsalicylic acid 50 mg/day starting at 12 h post-surgery until discharge, when it is increased up to 100 mg/day.

Infections and De Novo Neoplasms

Infections were considered when requirement for hospital admission. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) prophylaxis with valganciclovir was administered to all patients for 1 month post-transplant or three if a donor/recipient mismatch for CMV was present. Infection was defined as any replication in CMV load post-transplant, regardless of the presence of CMV disease. BK nephropathy was defined an increase in BK viremia >10.000 UI/mL, regardless of the presence of biopsy proven BK nephropathy.

De novo neoplasms were considered as any neoplasia diagnosed during the post-transplant period, including solid tumours, post-transplant lymphoprolipherative disorders (PTLD) and excluding non-melanoma skin cancer.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were recipient survival and death-censored kidney or pancreas graft survival at 1, 5, 10, and 20 years after transplantation, and graft rejection during follow up. Our secondary outcomes were defined as number of infections requiring hospital admission, CMV infection, BK virus nephropathy, and new onset neoplasms.

Patient survival was calculated from the date of transplantation to the date of death from any cause. Patients alive at the last follow-up were censored at that date. Pancreas graft failure was defined as any of the following: a) graft removal, b) C-peptide <1 ng/mL or c) total daily insulin dose >0.5 U/Kg.

Kidney graft failure was defined as return to dialysis or re-transplantation. Kidney DGF was defined as the need for at least one session of hemodialysis during the first week following SPKT.

Graft survival was analyzed using death-censored estimates to evaluate the effect of induction therapy on graft failure, particularly from immunological causes, independent of patient mortality. Nevertheless, to reduce the risk of bias derived from potential competing risks between recipient death and graft failure, a competing risk analysis was also performed.

Rejection Diagnosis and Treatment

All rejection episodes (for both pancreas and kidney) were biopsy-proven. Diagnostic criteria were based on the Banff classification in use at the time of diagnosis for either pancreas or kidney grafts. In cases of pancreas T cell–mediated rejection (TCMR), patients received three doses of methylprednisolone (500 mg/day) followed by five doses of thymoglobulin (1.25 mg/kg/day). For pancreas antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR), treatment consisted of three doses of methylprednisolone (250 mg/day), two doses of rituximab (400 mg/day), and five sessions of plasma exchange. For kidney graft rejection, the same therapeutic protocols were applied, except in cases of TCMR grade I, in which thymoglobulin was not administered.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation, SD) for continuous variables and median [interquartile range (IQR)] for the non-continuous ones. The corresponding tests used were t-test, Mann-Whitney test, Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact test as appropriated. Competing risk analysis for graft survival was performed using the Fine–Gray subdistribution hazard model.

Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to account for covariate imbalance between basiliximab and thymoglobulin groups. IPTW was estimated from a propensity score from a logistic regression model to receive basiliximab as the induction agent. The model included factors associated with the donor and either of the outcomes: dialysis duration before transplant, diabetes duration before transplant, time on the waiting list, HLA mismatches between donor and recipient, type of maintenance immunosuppression, prednisone withdrawal, recipient age at transplantation, cold ischemia time for kidney graft, Pancreas Donor Risk Index (PDRI), pancreas transplantation era, recipient smoking habit, cPRA before transplant.

A stabilized weighting method was performed by multiplying the IPTW by the proportion of recipients treated with basiliximab and thymoglobulin. Check for adequate balance of covariates after IPTW analyses was performed by calculation of standardized differences and an absolute difference greater than 0.2 represented a meaningful imbalance. All subsequent analyses were performed on the weighted, covariate-balanced population. Kaplan-Meier was used to estimate patient and graft survival and compared using a log-rank test. Logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratio for graft rejection, infections and neoplasms, and Cox proportional regression was performed to estimate patient and graft hazards.

All variables analyzed presented less than 10% of missing values. Given the low percentage, imputation methods were not applied, and analyses were conducted with the available data.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 30.0 (SPSS, Inc; Chicago, Illinois) software for MacOS and Python programming language (Python Software Foundation, 2024) in MacOS. All tests were two-tailed and a significance of 0.05 was used. Graphs were generated using the Python programming language in MacOS.

Results

Recipient and Donor Characteristics

A total number of 305 SPKT recipients were included in the study (Table 1). In 172 (56%), thymoglobulin was used as the induction agent, while in 133 (44%) basiliximab was administered as the induction therapy. The mean follow up time for the whole cohort was 12.08 ± 6.84 years. Recipient age at SPKT was similar between both groups. Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) was predominant in both groups, in which diabetes duration was also similar. Most of the patients were on dialysis at SPKT in both groups, although time on dialysis before transplant was higher in the basiliximab one, as well as time on the waiting list. Smoking habit was more frequent in the basiliximab group, as well as patients at high risk of CMV infection.

TABLE 1

| Thymoglobulin (n = 172) | Basiliximab (n = 133) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Male) | 102 (59) | 88 (66) | 0.24 |

| Ethnicity | 0.59 | ||

| Caucasian | 162 (94) | 128 (95) | |

| Hispanic | 9 (5) | 5 (5) | |

| Asian | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Age at SPKT (years) | 40.56 ± 7.58 | 40.96 ± 7.19 | 0.64 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.60 ± 5.30 | 22.90 ± 5.40 | 0.26 |

| Diabetes Mellitus type | 1.00 | ||

| Type 1 | 171 (99) | 132 (99) | |

| Type 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Other types | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Diabetes Mellitus duration at SPKT (years) | 25 [21–31] | 24 [20–31] | 0.11 |

| Dialysis before transplant | 146 (85) | 117 (88) | 0.50 |

| Dialysis duration (months) | 23 [13–34] | 31 [21–40] | <0.001 |

| Waiting list duration at SPKT (months) | 10.5 [4.75–18.25] | 17 [9–27] | 0.002 |

| Retinopathy | 168 (98) | 126 (95) | 0.22 |

| Neuropathy | 91 (53) | 60 (45) | 0.17 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 16 (10) | 22 (17) | 0.08 |

| Peripheral Artery Disease | 44 (26) | 41 (31) | 0.37 |

| Hypertension | 121 (70) | 86 (65) | 0.50 |

| Smoking habit | 57 (40) | 72 (54) | 0.04 |

| Transplant era (after 2008) | 120 (69) | 82 (62) | 0.15 |

| High risk of CMV infection | 13 (8) | 26 (20) | 0.003 |

| Total HLA mismatches | 0.38 | ||

| 0–2 | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| 3–4 | 30 (17) | 20 (15) | |

| ≥5 | 140 (82) | 113 (85) | |

| cPRA pre-transplant >5% | 8 (5) | 8 (6) | 0.61 |

| Maintenance immunosuppression | 0.22 | ||

| FK + MMF | 164 (95) | 129 (97) | |

| FK + mTORi | 6 (4) | 1 (1) | |

| CsA + MMF | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | |

| Prednisone withdrawal | 46 (27) | 44 (33) | 0.31 |

| Tacrolimus trough levels (ng/mL) | |||

| 1 month | 10.86 ± 2.82 | 11.82 ± 1.46 | 0.49 |

| 6 months | 9.66 ± 1.66 | 9.80 ± 0.92 | 0.44 |

| 12 months | 9.14 ± 1.02 | 8.32 ± 1.28 | 0.27 |

| 5 years | 7.52 ± 0.94 | 7.07 ± 0.53 | 0.37 |

| Kidney DGF | 13 (8) | 17 (13) | 0.17 |

Baseline characteristics of included recipients.

Data are means ± SD, n (%) or median [IQR] unless otherwise indicated. SPKT, simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation; BMI, body mass index; CMV, cytomegalovirus; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; cPRA, calculated Panel Reactive Antibody; PDN, prednisone; FK, tacrolimus; MPS, mycophenolate; mTORi, mTOR, inhibitors; CsA, cyclosporine; DGF, delayed graft function.

Table 2 summarizes donor characteristics. Age at donation was similar between both groups. No differences were observed for PDRI score among the studied groups. Donors after Circulatory Death (DCD) were more frequent in the thymoglobulin group. Pancreas and kidney Cold Ischemia Time (CIT) were longer in the basiliximab one.

TABLE 2

| Thymoglobulin (n = 172) | Basiliximab (n = 133) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Male) | 100 (60) | 81 (61) | 0.91 |

| Age (years) | 32.85 ± 12.22 | 32.43 ± 10.55 | 0.76 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.72 ± 3.28 | 23.47 ± 2.94 | 0.54 |

| Hypertension history | 12 (8) | 4 (3) | 0.07 |

| Smoking habit | 40 (28) | 34 (28) | 1.00 |

| Alcohol consumption | 15 (10) | 6 (5) | 0.11 |

| PDRI risk | 1.35 ± 0.61 | 1.30 ± 0.38 | 0.55 |

| ICU Length of Stay (days) | 2 [1–4] | 2 [1–5] | 0.64 |

| Donation after Circulatory Death | 22 (15) | 2 (2) | <0.001 |

| Pancreas CIT (hours) | 8.77 ± 2.54 | 11.19 ± 3.11 | <0.001 |

| Kidney CIT (hours) | 10.93 ± 2.82 | 13.36 ± 3.23 | <0.001 |

Donor characteristics.

Data are means ± SD, n (%) or median [IQR] unless otherwise indicated. BMI, body mass index; PDRI, pancreas donor risk index; ICU, intensive care unit; CIT, cold ischemia time.

After IPTW adjustment, no significant differences were observed between both groups neither for recipient nor for donor characteristics. Supplementary Table S1 shows standardized differences for donor and recipient characteristics before and after IPTW adjustment.

Recipient Survival

Patient survival at 1, 5, 10, and 20 years after SPKT was 98.8%, 98.1%, 94% and 86.2% in the thymoglobulin group, respectively. For basiliximab group, survival was not significantly different, being 99.2%, 94.6%, 92.2% and 80.5% for the same time periods, respectively (Log Rank P = 0.31) (Figure 1A). Unadjusted Cox regression analysis showed that basiliximab was not associated with an increased risk of patient death compared to thymoglobulin [HR 1.47 (0.69–3.14), P = 0.32]. A similar scenario was observed after IPTW adjustment, with no difference for patient death comparing both groups [HR 1.01 (0.43–2.34) for basiliximab group, P = 0.99] (Table 3). The main cause of recipient death in both groups were infections (50% vs. 37% for thymoglobulin and basiliximab groups, respectively), followed by neoplasms (34% vs. 26% for thymoglobulin and basiliximab, respectively), with no differences between groups (P = 0.55) (Supplementary Table S2).

FIGURE 1

TABLE 3

| HR [95% CI]a | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-adjusted | ||

| Patient death | 1.47 [0.69–3.14] | 0.32 |

| Pancreas graft failure | 1.08 [0.55–2.10] | 0.83 |

| Kidney graft failure | 0.80 [0.38–1.70] | 0.56 |

| IPTW-weighted | ||

| Patient death | 1.01 [0.43–2.34] | 0.99 |

| Pancreas graft failure | 1.57 [0.75–3.28] | 0.24 |

| Kidney graft failure | 1.49 [0.84–2.63] | 0.17 |

Non-adjusted and IPTW-weighted Cox regression for patient, pancreas and kidney graft survival.

The Thymoglobulin group was considered the reference group.

Pancreas Graft Survival

In the thymoglobulin group, pancreas death-censored graft survival at 1, 5, 10, and 20 years after SPKT was 95.9%, 93.1%, 88%, 86.1%, respectively. For basiliximab one, pancreas graft survival was similar, being 95.5%, 90.7%, 88.2%, 83.3% for the same time periods, respectively (Log Rank P = 0.83) (Figure 1B). No differences were observed for overall pancreas graft survival (Log Rank P = 0.57, Supplementary Figure S1A). Unadjusted Cox regression analysis showed no increased risk of pancreas failure with basiliximab compared to thymoglobulin as induction [HR 1.08 (0.55–2.10), P = 0.83]. These results were maintained after IPTW weighting [HR 1.57 (0.75–3.28) for basiliximab group, P = 0.24] (Table 3). A similar scenario was observed when performing a competing risk analysis, with a HR 0.93 [0.48–1.83], P = 0.84 for the basiliximab group.

Kidney Graft Survival

Kidney graft survival rates in the thymoglobulin group at 1, 5, 10, and 20 years post-SPKT were 97.1%, 95.5%, 89%, and 84.7%, respectively. Similarly, kidney graft survival in the basiliximab group was 98.5%, 94.6%, 90.4%, and 89.6% at the corresponding time points (Log Rank P = 0.56) (Figure 1C). No differences were observed for overall kidney graft survival (Log Rank P = 0.99, Supplementary Figure S1B). According to unadjusted Cox regression analysis, there was no significant increase in the risk of kidney graft failure with basiliximab when compared to thymoglobulin [HR 0.80 (0.38–1.70), P = 0.56]. This finding remained consistent following IPTW adjustment [HR 1.49 (0.84–2.63) for the basiliximab group, P = 0.17] (Table 3). A similar scenario was observed when performing a competing risk analysis, with a HR 1.24 [0.57–2.70], P = 0.58 for the basiliximab group.

Graft Rejection

Throughout the entire follow-up period, 34 pancreas rejection episodes (20%) occurred in the thymoglobulin group and 32 episodes (24%) in the basiliximab group, with no statistically significant difference between them (P = 0.40) (Table 4). Rejection occurred after a median time of 4 [1–23] and 6 [1–13] months for the thymoglobulin and basiliximab groups, respectively (P = 0.69).

TABLE 4

| Thymoglobulin (n = 172) | Basiliximab (n = 133) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreas rejection | 34 (20) | 32 (24) | 0.40 |

| ABMR | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.06 |

| TCMR | 29 (17) | 32 (24) | |

| Kidney rejection | 11 (7) | 14 (11) | 0.19 |

| ABMR | 5 (3) | 2 (2) | 0.10 |

| TCMR | 6 (4) | 12 (9) |

Pancreas and kidney graft rejection during follow up.

Data are n (%). ABMR, Antibody-Mediated Rejection. TCMR, T Cell-Mediated Rejection.

In both groups, the most frequent type of pancreas rejection was TCMR, with 29 (17%) and 32 (24%) cases for thymoglobulin and basiliximab, groups, respectively. There was no statistical support for an association between rejection type and treatment group (P = 0.06). However, a tendency toward a different rejection pattern was observed for the pancreas graft: in the basiliximab group, all cases were TCMR, whereas in the thymoglobulin group, 3% of cases were ABMR. Pancreas graft rejection was the cause of graft loss in 14 cases in the thymoglobulin group and 11 cases in the basiliximab group, representing 82% and 61% of all graft losses (41% and 34% of treatment failure), respectively (P = 0.16).

Kidney graft rejection rate was similar between thymoglobulin and basiliximab groups, observing 11 (7%) and 14 (11%) kidney graft rejection episodes (P = 0.19). Rejection occurred after a median time of 8 [1–53] and 8 [2–44] months for the thymoglobulin and basiliximab groups, respectively (P = 0.93).

The most frequent type in both groups was TCMR (4% and 9% in the thymoglobulin and basiliximab groups, respectively). No statistically significant association was found between rejection type and treatment group (P = 0.10) (Table 4). Kidney graft rejection was the cause of graft loss in 2 cases in the thymoglobulin group and 1 case in the basiliximab group, representing 13% and 8% of all graft losses (18% and 7% of treatment failure), respectively (P = 0.63).

When assessing the risk of graft rejection, basiliximab was not associated with a higher risk of rejection, either for pancreas [OR 1.28 (0.74–2.22), P = 0.37] or kidney graft [OR 1.72 (0.76–3.93), P = 0.20] compared to thymoglobulin. These results were consistent after IPTW weighting, with an OR of 1.49 [0.84–2.63] (P = 0.17) for pancreas and 1.31 [0.54–3.15] (P = 0.55) for kidney graft and basiliximab compared to thymoglobulin (Table 5).

TABLE 5

| OR [95% CI]a | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-adjusted | ||

| Pancreas graft rejection | 1.28 [0.74–2.22] | 0.37 |

| Kidney graft rejection | 1.72 [0.76–3.93] | 0.20 |

| IPTW-weighted | ||

| Pancreas graft rejection | 1.49 [0.84–2.63] | 0.17 |

| Kidney graft rejection | 1.31 [0.54–3.15] | 0.55 |

Non-adjusted and IPTW-weighted logistic regression for pancreas and kidney graft rejection.

The Thymoglobulin group was considered the reference group.

Infections and New Onset Neoplasms

The rate of post-transplant infections (except for CMV and BKV) that required patient admission was similar between thymoglobulin and basiliximab (35% vs. 38%, respectively. P = 0.55). Infections occurred after a median time of 35 [1–109] and 34 [22–80] days for thymoglobulin and basiliximab, respectively (P = 0.57) Nevertheless, when specifically considering CMV infection and BK nephropathy, thymoglobulin group exhibited a significantly higher rate of CMV infection (29% vs. 14% for thymoglobulin vs. basiliximab, respectively. P = 0.002) and BK nephropathy (12% vs. 4%, P = 0.01) (Table 6). CMV infection occurred after a median time of 3 [2–5] and 3 [1–5] months (P = 0.42), while BK infection occurred after a median time of 9 [6–30] and 28 [23–30] months for thymoglobulin and basiliximab, respectively (P = 0.40). Induction with basiliximab was significantly associated with a reduced risk of CMV infection [OR 0.39 (0.21–0.70), P = 0.002] and BK nephropathy (OR 0.28 [0.10–0.77], P = 0.01) compared to thymoglobulin (Table 7). This association was maintained after IPTW adjustment (OR 0.41 [0.23–0.72], P = 0.002 for basiliximab and CMV infection; OR 0.31 [0.12–0.80], P = 0.02 for basiliximab and BK infection).

TABLE 6

| Thymoglobulin (n = 172) | Basiliximab (n = 133) | |

|---|---|---|

| Infections that require hospitalization | 59 (35) | 51 (38) |

| CMV infection | 48 (29) | 18 (14) |

| BK infection | 21 (12) | 5 (4) |

| New onset neoplasms | 11 (6) | 14 (10) |

| PTLD | 2 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Breast | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Melanoma | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Colon | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Kidney | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Other | 2 (1) | 4 (3) |

Infections and new onset neoplasms during follow up.

Data are expressed as n (%). CMV, cytomegalovirus; PTLD, Post-Transplant Lymphoproliferative Disease.

TABLE 7

| OR [95% CI] | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-adjusted | ||

| Infections that require hospitalization | 1.18 [0.74–1.89] | 0.49 |

| CMV infection | 0.39 [0.21–0.70] | 0.002 |

| BK infection | 0.28 [0.10–0.77] | 0.01 |

| New onset neoplasms | 1.72 [0.76–3.93] | 0.20 |

| IPTW adjusted | ||

| Infections that require hospitalization | 1.45 [0.92–2.33] | 0.11 |

| CMV infection | 0.41 [0.23–0.72] | 0.002 |

| BK infection | 0.31 [0.12–0.80] | 0.02 |

| New onset neoplasms | 1.24 [0.48–3.21] | 0.66 |

Non-adjusted and IPTW-weighted logistic regression for infection and new-onset neoplasms.

The Thymoglobulin group was considered the reference group. CMV, cytomegalovirus.

The incidence of new onset neoplasms was similar between both groups (6% vs. 10% for thymoglobulin and basiliximab groups, respectively, P = 0.21). Median time to neoplasm diagnosis was 73 [39–90] and 170 [95–201] months for thymoglobulin and basiliximab groups, respectively (P = 0.08). In this case, no significant association was identified between basiliximab and neoplasm development compared to thymoglobulin, either in the unadjusted [OR 1.72 (0.76–3.93), P = 0.20] or IPTW-weighted analysis [OR 1.24 (0.48–3.21), P = 0.66] (Tables 6, 7).

Discussion

T-cell depleting agents (as thymoglobulin or alemtuzumab) and the IL2R blocker basiliximab have become the most frequently used induction agents in SPKT [5, 8, 13]. Nevertheless, information regarding post-transplant outcomes for each treatment remains controversial. Thus, in the present study we retrospectively compared post-transplant outcomes in a cohort of low immunological risk SPKT recipients after using either thymoglobulin or basiliximab as induction agents, focusing on long-term patient and grafts survival, as well as the incidence of post-transplant infections and neoplasms. Recipient, pancreas and kidney graft survival were similar among the two studied groups, as well as the incidence of graft rejection. Remarkably, basiliximab was not associated with a higher risk of pancreas and kidney graft rejection but significantly reduced the risk of CMV and BKV infection compared to thymoglobulin.

A multicenter randomized clinical trial demonstrating the benefit of induction therapy in SPKT was published in 2003 and ever since the use of induction therapy in pancreas transplantation has become almost ubiquitous [13, 14]. In this study, no differences were observed on 12-month graft survival between T-cell depleting agents or IL2R blockers. Nevertheless, in 2015, Kopp et al [15] reported a higher rate of pancreas rejection with IL2R blockers compared to Thymoglobulin in a long-term follow up study over 30 years in pancreas transplantation, although no differences in graft survival were observed. Since then, T-cell depleting agents have progressively gained relevance over IL2R blockers in the last decade, representing up to 80% of induction agent used in the USA [14]. Some studies have previously compared T-cell depleting agents and IL2R blockers as induction therapy in SPKT [9, 10, 16]. In 2011, Bazerbachi et al [9]. reported no differences for recipient and pancreas graft survival after 5 years, although basiliximab increased by 7-times the risk of pancreas TCMR at 1 year. Similar results were reported by Aziz et al [10] with a larger cohort of pancreas recipients. Remarkably, no increased risk of pancreas rejection was observed when only low immunological risk patients were considered (defined as cPRA <10%), although no information about pre-transplant DSAs was available. Our results are in line to those reported by Aziz et al, although with a longer follow up. Furthermore, in our study we considered as low immunological risk patients those with a cPRA <20% and no pre-transplant DSAs. The gap between cPRA cut off may be explained by the possibility to measure DSAs before transplant, which would allow to consider patients with a cPRA between 10% and 20% as low risk cases. Nevertheless, although no statistically significant differences in kidney or pancreas rejection rates were observed between thymoglobulin and basiliximab, our data showed a numerical trend toward higher rejection in the basiliximab group, as previously reported in other studies [17, 18]. Nevertheless, this tendency did not translate into inferior long-term graft or patient survival. This observation highlights the importance of careful recipient selection when considering basiliximab to avoid clinically relevant increases in rejection.

Thymoglobulin has also become the preferred induction agent in DCD pancreas transplantation due to a theoretically increased risk of rejection because higher severity of ischemia-reperfusion injury compared to Donors After Brain Death (DBD) [19]. Different studies have demonstrated that pancreas graft survival, patient survival, and rates of acute rejection are equivalent between DCD and DBD pancreas transplants, although thymoglobulin is the most frequent induction agent [19–21]. In our study, the proportion of DCD donors was higher in the thymoglobulin group, although CIT for both pancreas and kidney grafts were slightly longer in the basiliximab group. These findings suggest that basiliximab may also be effective in settings involving prolonged CIT. However, the higher incidence of DCD donors in the thymoglobulin group limits the ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy of basiliximab in DCD transplants. This underscores the need for individualized selection of induction therapy based on the specific donor–recipient profile.

Post-transplant infections and neoplasms are two of the most important complications associated with T-cell depleting agents because their profound immunosuppressant effect [11, 12]. In our cohort, thymoglobulin was associated with an increased risk of CMV infection (up to 60%) compared to basiliximab. Noticeably, this observation persisted even when adjusting for confounding factors and considering that a higher number of recipients with CMV mismatch were present in the basiliximab group. These data are in line to those reported previously [10]. Similar to CMV, thymoglobulin increased the risk of BK virus infection up to 70% compared to basiliximab, a finding that has been previously suggested but no solidly demonstrated in those studies comparing thymoglobulin and basiliximab in SPKT [9, 10, 16]. No differences in the risk of post-transplant neoplasms were observed between the two study groups; however, neoplasms tended to occur earlier in the thymoglobulin group, suggesting a potential adverse effect associated with thymoglobulin use. Moreover, it has to be considered that, according to our center policy, induction with basiliximab was changed to thymoglobulin after 2013, thus conferring to the thymoglobulin cohort a shorter follow up that can falsely reduce the incidence of new onset neoplasms.

The results of our study reinforce some of the recommendations from the First World Consensus Conference on Pancreas Transplantation, particularly those regarding the impact of non-depleting agents on patient and graft outcomes [5]. In addition, the observed tendency toward earlier neoplasm development may support concerns about a higher risk of oncologic complications with depleting agents, an issue also highlighted in that Consensus.

Although our study focused on thymoglobulin and basiliximab as induction agents, these findings may also be relevant when evaluating alemtuzumab, another T-cell depleting agent used in pancreas transplantation. Previous studies in pancreas transplantation have suggested that alemtuzumab achieve comparable graft and recipient outcomes to thymoglobulin [22–24]. In this context, our findings indicating that basiliximab provides equivalent long-term outcomes to thymoglobulin, with a lower incidence of CMV and BK virus infection, raise the possibility that non-depleting IL2R blockers might offer a safer alternative even in comparison to alemtuzumab, at least for carefully selected low-risk recipients. This hypothesis has been recently addressed in a retrospective study performed by Swaab et al. [25]. They reported similar short-term graft outcomes between IL2R blockers and alemtuzumab induction in a small cohort of SPKT recipients, in line with previous studies [10]. Future studies directly comparing basiliximab, thymoglobulin, and alemtuzumab could therefore provide valuable guidance for tailoring induction therapy according to individual immunologic risk and infection susceptibility.

An additional consideration arising from our results is the potential role of “no induction” protocols in selected SPK recipients. Our cohort included exclusively SPK recipients, a population known to have lower immunologic risk compared with other pancreas transplant modalities (pancreas transplant alone and pancreas after kidney), and further restricted to low-risk immunologic profiles [17, 18, 26]. Given this context and the outcomes observed, it is conceivable that similar results could be achieved in carefully selected low-risk SPK recipients even without induction therapy, as has been suggested in prior studies [27, 28]. Therefore, future prospective studies are warranted to evaluate this strategy and to identify the patient characteristics that may allow safe omission of induction therapy.

Our study has the inherent limitations of a single-center, retrospective design. In addition, the two induction treatments were administered during different time periods, so a potential year effect cannot be entirely excluded. The choice of induction therapy followed institutional policy, with a transition from basiliximab to thymoglobulin after 2013. Nevertheless, the single-center setting ensured a homogeneous cohort, particularly in terms of SPKT management and treatment protocols, thereby reducing the risk of bias. Furthermore, our analysis accounted for improvements in pancreas transplantation observed since 2008, which also helps minimize bias related to the different administration periods of thymoglobulin and basiliximab.

With a follow-up period spanning 20 years, our findings add valuable long-term data on induction therapy in SPKT. Specifically, our results indicate that in recipients with low immunological risk, basiliximab offers comparable patient and graft survival outcomes to thymoglobulin, while being associated with a lower incidence of opportunistic infections post-transplantation. Randomized controlled trials are necessary to draw definitive conclusions about the optimal induction therapy for SPKT.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Comité d’Ètica per a la Investigació amb Medicaments (HCB/2025/0613). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

EM-M: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. AR-G: Investigation, Writing – original draft. JV-M: Investigation, Writing – original draft. BMÁ: Investigation, Writing – original draft. IR: Investigation, Writing – original draft, AB: Investigation, Writing – original draft. JF-F: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. AA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. MR-B: Methodology, Writing – review and editing. MM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review and editing, FD: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing. PV-A: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ti.2025.15263/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

ABMR, Antibody-Mediated Rejection; CIT, Cold Ischemia Time; CMV, Cytomegalovirus; cPRA, Calculated Panel Reactive Antibody; DBD, Donor After Brain Death; DCD, Donor after Circulatory Death; DGF, Delayed Graft Function; DM, Diabetes Mellitus; DSA, Donor Specific Antibodies; ESKD, End-Stage Kidney Disease; IPTW, Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting; IQR, Interquartile Range; MFI, Mean Fluorescence Intensity; PDRI, Pancreas Donor Risk Index; PTLD, Post-Transplant Lymphoprolipherative Disorders; SD, Standard Deviation; SPKT, Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation; TCMR, T Cell-Mediated Rejection.

References

1.

EsmeijerKHoogeveenEKVan Den BoogPJMKonijnCMallatMJKBaranskiAGet alSuperior long-term Survival for Simultaneous pancreas-kidney Transplantation as Renal Replacement Therapy: 30-Year follow-up of a Nationwide Cohort. Diabetes Care (2020) 43(2):321–8. 10.2337/dc19-1580

2.

LindahlJPHartmannAAakhusSEndresenKMidtvedtKHoldaasHet alLong-Term Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 1 Diabetic Patients After Simultaneous Pancreas and Kidney Transplantation Compared with Living Donor Kidney Transplantation. Diabetologia (2016) 59(4):844–52. 10.1007/s00125-015-3853-8

3.

Montagud-MarrahiEMolina-AndújarAPanéARuizSAmorAJEsmatjesEet alImpact of Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation on Cardiovascular Risk in Patients With Diabetes. Transplantation (2022) 106:158–66. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003710

4.

PoseggerKRLinharesMMMucciSRomanoTMGonzalezAMSalzedas NettoAAet alThe Quality of Life in Type I Diabetic Patients with end-stage Kidney Disease Before and After Simultaneous pancreas-kidney Transplantation: A single-center Prospective Study. Transpl Int (2020) 33(3):330–9. 10.1111/TRI.13562

5.

BoggiUVistoliFAndresAArbogastHPBadetLBarontiWet alFirst World Consensus Conference on Pancreas Transplantation: Part II – Recommendations. Am J Transplant (2021) 21(S3):17–59. 10.1111/AJT.16750

6.

DongMParsaikAKKremersWSunADeanPPrietoMet alAcute Pancreas Allograft Rejection Is Associated with Increased Risk of Graft Failure in Pancreas Transplantation. Am J Transplant (2013) 13(4):1019–25. 10.1111/AJT.12167

7.

AzizFMandelbrotDParajuliSAl-QaoudTRedfieldRKaufmanDet alAlloimmunity in Pancreas Transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transpl (2020) 25(4):322–8. 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000776

8.

NiederhausSVKaufmanDBOdoricoJS. Induction Therapy in Pancreas Transplantation. Transpl Int (2013) 26(7):704–14. 10.1111/TRI.12122

9.

BazerbachiFSelznerMBoehnertMUMarquezMANorgateAMcGilvrayIDet alThymoglobulin Versus Basiliximab Induction Therapy for Simultaneous Kidney-Pancreas Transplantation: Impact on Rejection, Graft Function, and long-term Outcome. Transplantation (2011) 92(9):1039–43. 10.1097/TP.0B013E3182313E4F

10.

AzizFParajuliSKaufmanDOdoricoJMandelbrotD. Induction in Pancreas Transplantation: T-Cell Depletion Versus IL-2 Receptor Blockade. Transpl Direct (2022) 8(12):E1402. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001402

11.

RomaoEAYamamotoAYGasparGGGarciaTMPMugliaVANardinMEPet alSignificant Increase in Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection in Solid Organ Transplants Associated with Increased Use of Thymoglobulin as Induction Therapy?Transpl Proc (2023) 55(9):2035–40. 10.1016/J.TRANSPROCEED.2023.08.021

12.

WangLMotterJBaeSAhnJBKanakryJAJacksonJet alInduction Immunosuppression and the Risk of Incident Malignancies Among Older and Younger Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Transpl (2020) 34(12):e14121. 10.1111/CTR.14121

13.

KaufmanDBBurkeGWBruceDSJohnsonCPGaberAOSutherlandDERet alProspective, Randomized, Multi-Center Trial of Antibody Induction Therapy in Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation. Am J Transplant (2003) 3(7):855–64. 10.1034/J.1600-6143.2003.00160.X

14.

KandaswamyRStockPGMillerJMHandarovaDIsraniAKSnyderJJ. OPTN/SRTR 2023 Annual Data Report: Pancreas. Am J Transplant (2025) 25(2):S138–S192. 10.1016/J.AJT.2025.01.021

15.

KoppWHVerhagenMJJBlokJJHuurmanVALde FijterJWde KoningEJet alThirty Years of Pancreas Transplantation at Leiden University Medical Center: Long-Term Follow-up in a Large Eurotransplant Center. Transplantation (2015) 99(9):e145–51. 10.1097/TP.0000000000000604

16.

Fernández-BurgosIMontiel CasadoMCPérez-DagaJAAranda-NarváezJMSánchez-PérezBLeón-DíazFJet alInduction Therapy in Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation: Thymoglobulin Versus Basiliximab. Transpl Proc (2015) 47(1):120–2. 10.1016/J.TRANSPROCEED.2014.12.003

17.

ParajuliSArunachalamASwansonKJAzizFGargNRedfieldRRet alOutcomes After Simultaneous Kidney-Pancreas Versus Pancreas After Kidney Transplantation in the Current Era. Clin Transpl (2019) 33(12):e13732. 10.1111/CTR.13732

18.

BazerbachiFSelznerMMarquezMANorgateAMcGilvrayIDSchiffJet alPancreas-After-Kidney Versus Synchronous pancreas-kidney Transplantation: Comparison of Intermediate-Term Results. Transplantation (2013) 95(3):489–94. 10.1097/TP.0B013E318274AB1A

19.

CallaghanCJIbrahimMCounterCCaseyJFriendPJWatsonCJEet alOutcomes After Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation From Donation After Circulatory Death Donors: A UK Registry Analysis. Am J Transpl (2021) 21:3673–83. 10.1111/ajt.16604

20.

ShahrestaniSWebsterACLamVWTYuenLRyanBPleassHCCet alOutcomes From Pancreatic Transplantation in Donation After Cardiac Death: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transplantation (2017) 101(1):122–30. 10.1097/TP.0000000000001084

21.

GopalJPMcLeanAMuthusamyA. Metabolic Outcomes After Pancreas Transplant Alone from Donation After Circulatory Death Donors-The UK Transplant Registry Analysis. Transpl Int (2023) 36:11205. 10.3389/ti.2023.11205

22.

StrattaRJRogersJOrlandoGFarooqUAl-ShraidehYDoaresWet alDepleting Antibody Induction in Simultaneous pancreas-kidney Transplantation: A Prospective Single-Center Comparison of Alemtuzumab Versus Rabbit Anti-thymocyte Globulin. Expert Opin Biol Ther (2014) 14(12):1723–30. 10.1517/14712598.2014.953049

23.

StrattaRJRogersJOrlandoGFarooqUAl-ShraidehYFarneyAC. 5-year Results of a Prospective, Randomized, single-center Study of Alemtuzumab Compared With Rabbit Antithymocyte Globulin Induction in Simultaneous Kidney-Pancreas Transplantation. Transpl Proc (2014) 46(6):1928–31. 10.1016/J.TRANSPROCEED.2014.05.080

24.

FarneyACDoaresWRogersJSinghRHartmannEHartLet alA Randomized Trial of Alemtuzumab Versus Antithymocyte Globulin Induction in Renal and Pancreas Transplantation. Transplantation (2009) 88(6):810–9. 10.1097/TP.0B013E3181B4ACFB

25.

SwaabTDAPolRACropMJSandersJSFBergerSPHofkerHSet alShort-Term Outcome After Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation With Alemtuzumab Vs. Basiliximab Induction: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Sci Rep (2025) 15(1):20732–10. 10.1038/S41598-025-06750-Y

26.

YangKHRyuJHShimJRLeeTBLeeHJKimSRet alThe Pancreas After Kidney Transplant Is a Competitive Option, Comparable to the Simultaneous Pancreas and Kidney Transplant. Transpl Proc (2024) 56(6):1347–52. 10.1016/J.TRANSPROCEED.2024.03.038

27.

NicoluzziJ. Successful Pancreas-Renal Transplantation Without Induction Therapy. Transpl Proc (2005) 37(10):4438–9. 10.1016/J.TRANSPROCEED.2005.11.027

28.

BeckerLENogueiraVAAbensurHMirandaMPGenziniTRomãoJEet alNo Induction Versus Anti-IL2R Induction Therapy in Simultaneous Kidney Pancreas Transplantation: A Comparative Analysis. Transpl Proc (2006) 38(6):1933–6. 10.1016/J.TRANSPROCEED.2006.06.072

Summary

Keywords

simultaneous kidney pancreas transplantation, thymoglobulin, basiliximab, opportunistic infections, neoplasm

Citation

Montagud-Marrahi E, Rodriguez-Gonzalo A, Vidiella-Martin J, Álvarez BM, Gaston Ramírez I, Baronet A, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Amor AJ, Ramírez-Bajo MJ, Musquera M, Diekmann F and Ventura-Aguiar P (2025) Impact of Induction Therapy in Low Immunological Risk Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation. Transpl. Int. 38:15263. doi: 10.3389/ti.2025.15263

Received

13 July 2025

Accepted

22 September 2025

Published

30 September 2025

Volume

38 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Montagud-Marrahi, Rodriguez-Gonzalo, Vidiella-Martin, Álvarez, Gaston Ramírez, Baronet, Ferrer-Fàbrega, Amor, Ramírez-Bajo, Musquera, Diekmann, Ventura-Aguiar.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pedro Ventura-Aguiar, pventura@clinic.cat

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.