Abstract

Uterine transplantation has revolutionized previously incurable causes of infertility. While most transplants are performed with live donors, the use of deceased donors could potentially expand the donor pool and increase the number of transplants performed. One limitation of deceased donor use is warm and cold ischemia time, which may be potentially mitigated by the implementation of ex-vivo machine perfusion (EVMP). This comprehensive review synthesizes the existing literature on uterine EVMP, highlighting both experimental and translational developments up to February 2025. A total of 31 relevant studies were identified from 244 screened articles, most involving human aor large-animal uteri. The majority of studies employed normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) as a model for physiologic conditions, focusing on endocrine or functional analysis, inflammatory reactions, or technical aspects of perfusion. Only in the past 6 years have articles looked at EVMP as a preservation technique for transplantation, or employed hypothermic machine perfusion (HMP). While EVMP has only recently increased in popularity for transplant preservation, uterine EVMP has historically been used in multiple studies as a model for physiologic conditions. While further research is needed to optimize preservation protocols, much can be gleaned from prior models of uterine perfusion.

Introduction

Absolute uterine factor infertility is a significant cause of infertility, and was considered incurable until the last decade. Uterine transplantation represents a revolutionary approach to addressing infertility in women with absent or nonfunctional uteri, which may result from congenital uterine agenesis or hysterectomy due to malignant disease, postpartum hemorrhage, uterine fibroids, and congenital abnormalities [1]. Distinct from other solid organ transplants, uterine transplant poses unique challenges; it must not only be technically and immunologically feasible but also enable the transplanted uterus to sustain pregnancy and facilitate a healthy live birth [2].

The first human uterine transplant attempt was conducted in 2000 [3], but the first live birth occurred in 2014 in Sweden [4]. Since then, over 80 uterine transplants have been performed globally, resulting in more than 40 live births [5, 6]. Approximately 72% of the registered uterine transplants were from live donors, according to the United States Uterus Transplant Consortium (USUTC) and the International Society of Uterus Transplantation (ISUTx) [5, 6]. However, recent research has now focused on using deceased (brain-dead) donors as graft sources. While this would potentially increase the donor pool, it also requires more attention to organ preservation.

Despite advancements in uterus transplantation, significant knowledge gaps persist, necessitating further research in surgical techniques, immune modulation, and graft rejection studies [7]. Moreover, the effects of warm and cold ischemia in uterus transplantation are still not well understood. Uterine grafts have been shown to tolerate static cold ischemic storage (SCS) for at least 6 h while maintaining histologic integrity, ATP concentrations, and contractile ability [8].

One concern in the field of uterine transplantation is the tolerance of the uterus to ischemia, and the effects of warm and cold ischemia on graft viability and functionality. According to previous studies using animal models, the uterus exhibits a relative tolerance to both cold and warm ischemia [9, 10]. In the mouse model of uterus transplantation, it has been demonstrated that live births can be achieved following a cold ischemia duration of 24 h [11]. However, the optimal duration of cold ischemia for uterine grafts remains undetermined, necessitating further investigation. During the 24 h of cold storage of human uterine, Gauthier et al, demonstrated that no significant histomorphology changes had occurred in the tissue, and there was little evidence of apoptosis [12]. In the clinical setting, live births have resulted from both living and deceased donors, although living donors comprise the majority of live births [5, 6]. Deceased donors have a significantly longer cold ischemia time (CIT) as compared to living donors [5], but successful live births have resulted from CIT as long as 6.5 h [13] and 9 h [14]. Among uterus transplants in the United States, early graft loss was associated with longer warm ischemia time (WIT), but no association was found between CIT and clinical outcomes [5].

SCS has long been considered the gold standard for organ preservation [15]. However, advancements in ex-vivo machine perfusion (EVMP) technology, originally developed for solid organs, have opened new avenues for preserving a wider range of organs and delivering therapeutic agents [15]. Previous large-scale studies have indicated that EVMP may offer advantages over SCS in liver and kidney transplants, including improved patient survival rates, reduced adverse events, and enhanced short- and long-term functional outcomes [16, 17]. In addition, EVMP may offer several advantages, such as reducing cold ischemia and hypoxic injuries by ensuring a continuous supply of oxygen and nutrients, clearing toxic metabolites, and improving the quality and viability of the graft [18, 19].

In clinical settings, this technique is now frequently applied for lung, heart, liver, and kidney transplantation [20–22]. In particular, EVMP has shown potential for extremity vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA), in which static cold storage typically requires reperfusion within 10–12 h to maintain viability, with optimal functional recovery anticipated between 3 and 6 h of cold ischemia [23]. The implementation of EVMP may be particularly important in uterus transplantation due to the non-vital nature of the uterus, which often leads to prolonged CIT during multi-organ procurement surgeries, as hysterectomies are performed as the last procedure in some protocols [24, 25].

Despite the growing fields of research in both uterus transplantation and EVMP, no comprehensive review papers exist on uterus machine perfusion. The purpose of this study is to conduct a extensive review of literature on uterus ex-vivo machine perfusion, including identification of relevant literature, characterization of these studies in terms of perfusion protocol and outcomes, and comparison of protocols.

Search Approach and Evidence Selection

A comprehensive literature search of manuscripts listed in PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and ClinicalTrials.gov databases was conducted in January 2025. The following search terms were used: [(uterus) OR (uteri) OR (uterine)] AND [(machine perfusion) OR (machine preservation) OR (ex vivo perfusion) OR (extracorporeal perfusion) OR (extracorporeal circulation)]. Selected studies met the following inclusion criteria: (1) preclinical articles studying machine perfusion; (2) perfusion of uterus grafts; (3) randomized control trials, prospective and retrospective case-control and cohort studies, cross-sectional cohort studies, case reports, and technique papers. Exclusion criteria were: (1) reviews without presentation of new data; (2) abstracts, conference papers, editorials, or comments; (3) articles about solid-organ or non-uterine VCA perfusion. Historically, however, perfusion systems have been extensively used for physiological and hormonal studies of the uterus, providing a valuable foundation for the future development of this approach in organ preservation. Despite the heterogeneity among existing studies, we included all such research in our review to capture the full scope of relevant evidence.

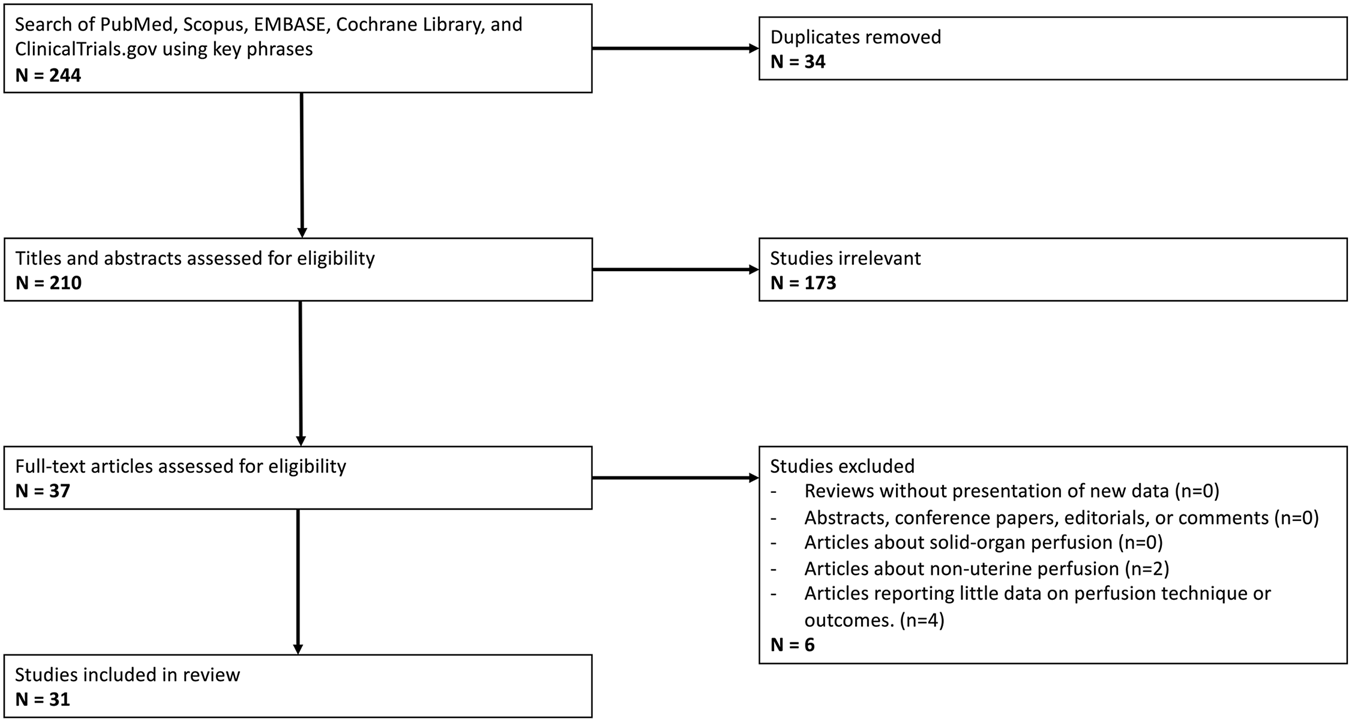

The literature search yielded 244 articles, of which 31 articles met criteria (see Figure 1; Table 1) [7, 26–33, 35–56]. Included studies were published between 1970 and 2025. Ten studies utilized human uteri, while the remaining 21 used animal models. Of these animal models, all but one were in large animals, with swine being the most common (15 studies). Other animals included sheep (2 studies), cows (2 studies), and horses (1 study). Only one study [28] used a small animal model (rabbits), and no studies used rodents.

FIGURE 1

PRISMA Flow Diagram outlining inclusion and exclusion criteria, number of abstracts screened, and full texts retrieved.

TABLE 1

| Author (Year) | Species (Details) | Surgical Details | Cannulation Details | Temp (°C) | Duration (Hr) | Flow (mL/min) | Pressure (mmHg) | Perfusion Pump Setup | Perfusate Details | Perfusion Monitoring | Study Design (# of uteri) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peirce [26] | Sheep (38–62 kg, near-term) | Pregnant uterus removed and placed in “artificial abdomen” | Bilateral uterine arteries | 37 | 0.5–5 | 300+ | NR | 2 roller pumps, artificial membrane lung for oxygenation | Heparinized maternal blood | Perfusate chemistry and gas | NMP [15] | Early fetal death early in all but 5 perfusions, survival up to 5 h in one experiment |

| Tojo [27] | Human | Hysterectomy for benign disease and trophoblastic tumor | Bilateral uterine arteries | 37 | 5 | 25–40 | NR | 1 diaphragm pump with Y-connector, oxygenator with oxygen | Hank’s solution, 20% autologous whole blood, 4% dextran | Perfusate chemistry and gas, EMG uterine muscle, biopsy tumor tissue, angiogram after perfusion | NMP [2] | Viability up to 5 h, preservation of trophoblastic tumor in utero |

| Bloch [28] | Rabbit (3–4 kg) | Single uterine horn included, contralateral blood supply ligated | Aorta | 37 | 7–10 | 6–8 | NR | 1 pump, oxygenator with carbogen | Krebs-henseliet buffer, dextran | Perfusate prostaglandin levels | NMP with angiotensin II, oxytocin, epinephrine, and arachidonic acid [29] | Increased prostacyclin release with all substances, most effectively for arachidonic acid |

| Bulletti [30] | Human | Scheduled hysterectomies for benign and malignant diseases | Bilateral uterine arteries and veins, 16G | 37 | 12 | 10–30 | 80–120 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | KRBB, heparin | Perfusate chemistry and gas, uterine biopsy | NMP [9] | Viability up to 12 h |

| Bulletti [31] | Human | Scheduled hysterectomies for benign and malignant diseases | Bilateral uterine arteries and veins, 16G | 37 | 48 | 12–35 | 80–120 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | KRBB, heparin | Perfusate chemistry and gas, uterine biopsy | NMP [20] | Viability up to 48 h, tissue is responsive to estrogen and progesterone |

| Bulletti [32] | Human | Scheduled hysterectomies for benign and malignant diseases | Bilateral uterine arteries and veins, 16G | 37 | 52 | 18–30 | 80–120 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | KRBB, heparin | Uterine biopsy | NMP after injection of fertilized embryo [3] | Successful implantation and trophoblastic invasion after 52 h in one of three uteri |

| Bulletti [33] | Human | Scheduled hysterectomies for benign and malignant diseases | Bilateral uterine arteries and veins, 16G | 37 | 1 | 30 | 120 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | KRBB, heparin | Perfusate estrogen levels, uterine biopsy | NMP with radio-labeled compounds to assess estrogen uptake [34] | Differential permeability of uterine vascular beds during proliferative and secretive phases |

| Bulletti [35] | Human (36–42 years) | Scheduled hysterectomies for benign and malignant diseases | Bilateral uterine arteries and veins, 16G | 37 | 1.5, 48 | NR | NR | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | KRBB, heparin | Perfusate chemistry and gas, IUP, EMG uterine muscle | NMP for 48 h [3] NMP for 1.5 h with estrogen [5], estrogen/progesterone [5] |

No spontaneous muscle activity in control uteri, increased muscle activity with estrogen, decreased with progesterone |

| Richter [36] | Human (28–56 years) | Scheduled hysterectomies for benign diseases | Bilateral uterine arteries, 14G | 37 | 24 | 15–35 | 70–130 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Modified KRBBa, gentamicin | Perfusate chemistry and gas, uterine biopsy | NMP without exchange [5] NMP with exchange every 1 h [5], 2 h [5], 4 h [5], 6 h [5] |

Increased damage with exchange every 6 h, viabillity in 1–4h groups |

| Baumer [37] | Cow (2+ years) | Post-mortem excision, 30–45 min WIT | Bilateral uterine arteries and veins | 39 | 5 | 12–17 | NR | 1 peristaltic pump with Y-connector, oxygenator with carbogen | Autologous whole blood plus tyrode solution (4:1 ratio), heparin | Perfusate chemistry and gas, uterine biopsy | NMP [4] NMP with addition of Lugol’s solution [4], arachidonic acid [5] |

Viability up to 5 h, adequate inflammatory response to irritants |

| Dittrich [38] | Swine (5–18 months) | Post-mortem excision | Bilateral uterine arteries and veins, 16–24G | 37 | 7 | 15 | 100 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen, no recirculation | Modified KRBBa, calcium carbonate | Perfusate chemistry and gas, IUP | NMP with oxytocin [15], PGE2 [15] | Viability up to 7 h, contractions induced by both oxytocin and PGE2 |

| Richter [29] | Human (34–46 years) | Scheduled hysterectomies for benign diseases | Bilateral uterine arteries, 14G | 37 | 27 | 15–35 | 70–130 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Modified KRBBa | Perfusate chemistry and gas, uterine biopsy | NMP with oxytocin [5], estradiol/oxytocin [5] | Increased oxytocin receptor concentration in estradiol/oxytocin group compared to oxytocin alone |

| Richter [39] | Human (31–46 years) | Scheduled hysterectomies for benign diseases | Bilateral uterine arteries, 14G | 37 | 27 | 15–35 | 70–130 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Modified KRBBa | Perfusate chemistry and gas, uterine biopsy | NMP [5] NMP with oxytocin [5], estradiol/oxytocin [5] |

Increased oxytocin receptor gene expression in estradiol/oxytocin group compared to oxytocin alone |

| Braun [40] | Cow (2+ years) | Post-mortem excision, 75 min WIT | Bilateral uterine arteries and veins | 39 | 6 | 17 | NR | 1 peristaltic pump with Y-connector, oxygenator with carbogen | Autologous whole blood plus tyrode solution (4:1 ratio), heparin | Perfusate chemistry and gas, uterine biopsy | NMP [6] NMP with addition of arachidonic acid [18] |

Viability up to 6 h, increased inflammatory markers in arachidonic acid exposure group |

| Maltaris [41] | Swine (5–18 months) | Post-mortem excision | Bilateral uterine arteries, 16–24G | 37 | 8 | 15 | 100 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Modified KRBBa | Perfusate chemistry and gas, IUP | NMP with acetylsalicylic acid [5], atosiban [5], ethanol [5], fenoterol [5], ritodrine [5], terbutaline [5], propofol [5], glyceryl trinitate [5], verapamil [5] | Increased contractility with all substances, most effectively with fenoterol |

| Mueller [42] | Swine (5–18 months) | Post-mortem excision | Bilateral uterine arteries, 16–24G | 37 | 8 | 15 | 100 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Modified KRBBa, oxytocin added to induce contractions | Perfusate chemistry and gas, IUP | NMP with estrogen [34], progesterone [34], estrogen/progesterone [34] | Estrogen increased contracility, progesterone antagonized effects of estrogen |

| Mueller [43] | Swine (5–18 months) | Post-mortem excision | Bilateral uterine arteries, 16–24G | 37 | 8 | 15 | 100 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Modified KRBBa | Perfusate chemistry and gas, IUP in corpus and isthmus | NMP with PGF2a [15], PGE1 [15], PGE2 [15], oxytocin [15] | Increased IUP globally with oxytocin and PGF2a, IUP gradient (isthmus > corpus) with PGE1 and PGE2 |

| Mueller [44] | Swine (5–18 months) | Post-mortem excision | Bilateral uterine arteries | 37 | 8 | 15 | 100 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Modified KRBBa, oxytocin added to induce contractions | Perfusate chemistry and gas, bilateral IUP | NMP with unilateral addition of estrogen [20], progesterone [20], estrogen/progesterone [20] | Estrogen increased contractility in ispilateral horn but not contralateral, progesterone antagonized effects of estrogen |

| Kunzel [45] | Swine (5–18 months) | Post-mortem excision | Bilateral uterine arteries, 16G | 37 | 8 | 15 | 100 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Modified KRBBa, oxytocin added to induce contractions | Perfusate chemistry and gas, IUP | NMP with butylscopolamine [12], atropine [13], denaverine [15], morphine [7], metamizole [9], pethidine [10], celandine [14] | Decreased contractility with all substances, most effectively for denaverine |

| Dittrich [46] | Swine (5–18 months) | Post-mortem excision, division into two horns for simultaneous perfusion | Bilateral uterine arteries, 16–24G | 37 | 3.5 | NR | NR | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Modified KRBBa, oxytocin added to induce contractions | Bilateral IUP | Simultaneous NMP of bilateral horns with unilateral addition of human seminal plasma [17] | Improved contractility on human seminal plasma side |

| Geisler [47] | Swine (5–18 months) | Post-mortem excision | Bilateral uterine arteries, 16G | 37 | 24 | 15 | NR | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | KRBB or modified KRBBa, oxytocin added to induce contractions | Perfusate chemistry and gas, IUP | NMP with KRBB [11], modified KRBBa [18], modified KRBB with exchange every 2 h [11] | Improved contractility with modified KRBBa, viability up to 17 h with perfusate exchange |

| Kunzel [48] | Swine (5–18 months) | Post-mortem excision | Bilateral uterine arteries, 16G | 37 | NR | 15 | 80–100 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Modified KRBBa | Perfusate chemistry and gas, IUP | NMP with PGE1 [3], PGE2 [3], PGF2a [3], progesterone/PGE1 [18], progesterone/PGE2 [16], progesterone/PGF2a [15] | Prostaglandin-induced contractions reduced by progesterone |

| Stirland [49] | Human | Scheduled hysterectomies for fibroids | Bilateral uterine arteries | 38 | 8 | NR | 100 | 1 peristaltic pump with Y-connector, oxygenator with carbogen | Krebs-henseleit buffer, heparin, gentamicin, insulin, glutathione | Perfusate chemistry and gas, uterine biopsy | NMP with methylene blue [14] | Poor methylene blue staining in fibroids |

| Oppelt [50] | Swine (5–18 months) | Post-mortem excision | Bilateral uterine arteries, 24G | 37 | 4 | 10–15 | 60–80 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Modified KRBBa | Perfusate chemistry and gas, IUP in corpus and isthmus | NMP control [18] NMP with progesterone [26], dienogest [38] |

Progesterone decreased contractility globally, dienogest decreased contractility at ithmus only |

| Weinschenk [51] | Swine (7–18 months) | Post-mortem excision, 20min WIT | Bilateral uterine arteries, 16G | 37 | 1 | 6 | NR | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Modified KRBBa | IUP | NMP with procaine [31], lidocaine [31], ropivacaine [32] | Lidocaine and ropivacaine reduce contracitlity in higher concentrations |

| Padma [7] | Sheep (9–12 months) | Post-mortem excision | Bilateral uterine arteries, 26G | 37 | 48 | NR | 45–55 | 1 peristaltic pump with Y-connector, oxygenator with carbogen | DMEM/F-12, GlutaMAX, fetal bovine serum, antibiotic-antimicotic solution | Perfusate chemistry and gas, uterine biopsy | SCS 4 h then NMP 48 h [6] SCS 48 h then NMP 48 h [7] |

Reperfusion damage in 48 h storage but not 4 h storage |

| Kohne [52] | Horse (8–25 years) | Post-mortem exicsion after exsanguination, 60–100 min WIT | Bilateral uterine and ovarian arteries, 14–18G | 39 | 8 | 30 | NR | 1 peristaltic pump with 3 Y-connectors, oxygenator with oxygen | Autologous whole blood plus autologous plasma (3:2 ratio), heparin | Perfusate chemistry and gas, uterine biopsy, sonomicrometry | NMP [12] | Viability up to 6 h, decreased function after 4 h s |

| Dion [53] | Swine | Uterus removed en bloc with aorta and IVC | Aorta | 4 | 18 | NR | NR | VitaSmart machine perfusion system (1 peristaltic pump) | UW solution | Macroscopic assessment | HMP 18h then transplant (NR) | Viable transplant |

| Loiseau [54] | Swine (150 kg) | Post-mortem excision, 60min WIT, uterus removed en bloc with aorta and IVC | Aorta | 4 (HMP) or 37 (NMP) | 12 (HMP) or 2 (NMP) | NR | 15 (HMP) or 30–35 (NMP) | VitaSmart machine perfusion system (1 peristaltic pump) (HMP) or liverassist machine perfusion system (1 peristaltic pump) (NMP) | UW solution (HMP) or heparinized autologous whole blood (NMP) | Perfusate chemistry and gas, uterine biopsy | SCS 12h then NMP 2h [5] HMP 12h then NMP 2h [5] |

Decreased resistance indices and higher tissue oxygenation during reperfusion in HMP group as compared to SCS |

| Cabanel [55] | Swine (30–40 kg) | Post-mortem excision, less than 60min WIT | Bilateral uterine arteries, 18G | 20 | 4 | 2.5–10 | 25–35 | 2 roller pumps, oxygenator with carbogen | Steen+ solution | Perfusate chemistry and gas, serial weights, post-perfusion angiography | SNMP [4] | Viability for 4 h perfusion, stable weight throughout perfusion, well-identified microvasculature post-perfusion |

| Sousa [56] | Swine | Uterus removed en bloc with aorta and IVC | Aorta | 4 | 18 | NR | 3 | VitaSmart machine perfusion system (1 peristaltic pump) | UW solution | Macroscopic assessment, uterine biopsy, post-transplant blood samples | SCS in HTK 18h then transplant [5] SCS in UW 18h then transplant [5] HMP 18h then transplant [5] |

Improved histology after transplant in HMP group initially but equivocal after 3 h, no biomarkers for uterus viability identified |

Summary of reviewed papers, n = 31.

NR, not recorded; WIT, warm ischemia time; NMP, normothermic machine perfusion; SNMP, sub-normothermic machine perfusion; HMP, hypothermic machine perfusion; SCS, static cold storage; IUP, intrauterine pressure; KRBB, Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer.

Modified KRBB, Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer with added saccharose, glutathione, dithiothreitol, 50 IU/L regular insulin.

Experimental Focus

The included studies comprise a variety of experimental aims. As machine perfusion has only recently increased in popularity for organ preservation, many of the total published works on uterus machine perfusion do not have an end goal of transplantation or organ preservation. The most common experimental aim was endocrine and/or functional analysis (16 studies), which involved contraction monitoring and biochemical analysis after the administration of various hormones, drugs, or prostaglandins. Another portion of studies focused on technical aspects of the perfusion (5 studies), including perfusate composition, perfusion flow and pressure, and the influence of perfusate exchange. Four studies analyzed EVMP as a storage method, comparing machine-perfused uteri to uteri stored statically on ice. Of these four studies, two included subsequent transplantation. Other experimental aims included EVMP as a model for inflammatory reactions (2 studies), preservation of a pregnant sheep uterus (1 study), preservation of an intrauterine trophoblastic tumor (1 study), in vitro fertilization of a machine-perfused uterus (1 study), and analysis of fibroid blood supply via addition of methylene blue (1 study).

Surgical Technique and Anatomical Considerations

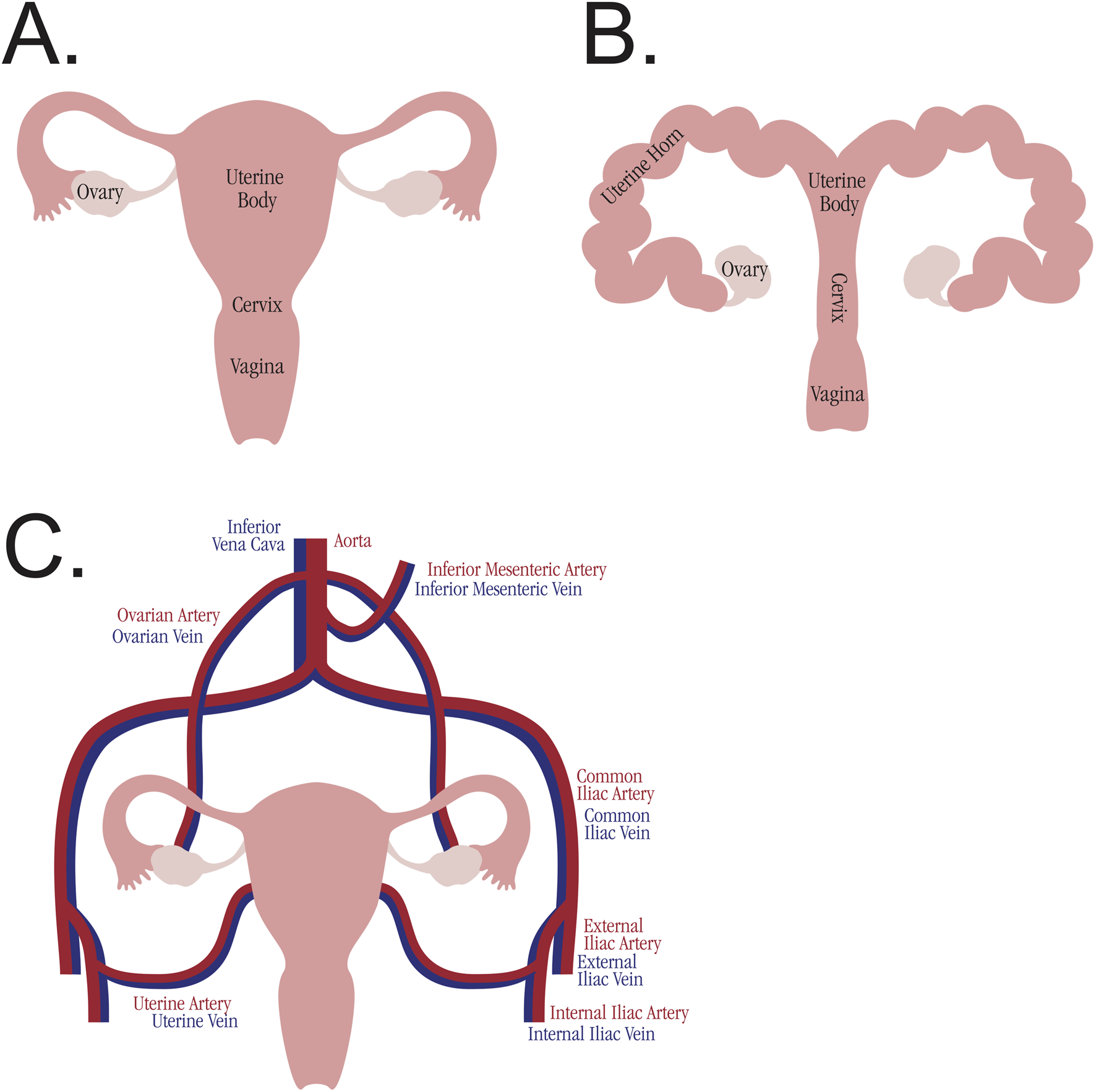

The uterus is relatively unique in its blood supply as compared to other transplants (see Figure 2). The majority of other solid organ transplants and VCAs have a single-artery and single-vein blood supply, allowing for simplified machine perfusion with a single roller pump. The body of the uterus (as well as the uterine horns in large animal anatomy) is perfused via bilateral uterine arteries, which arise from the bilateral internal iliac arteries. They drain via bilateral uterine veins (also referred to in humans as inferior uterine veins) [57], which drain into the bilateral internal iliac veins. The ovaries have a separate blood supply, bilateral ovarian arteries and veins, which originate directly from the aorta and drain directly into the inferior vena cava, respectively. In humans, the distal ovarian vein is referred to as the superior uterine vein, and accounts for a large portion of uterine venous drainage [57]. The majority of studies (27 studies) cannulated the bilateral uterine arteries. Of these studies, eight also cannulated the uterine veins bilaterally. One study cannulated both the uterine and ovarian arteries bilaterally, although the ovarian arteries do not provide a significant blood supply to the uterine body and are not utilized for anastomosis in uterine transplantation [57]. While the majority of studies kept the uterine body intact, one study divided the uterus along the midline to perfuse both sides simultaneously [46]. Another study, the only one to use a small animal model [28], isolated a single uterine horn and cannulated it through the abdominal aorta, ligating all other arterial branches. Three recent studies [53, 54, 56] use a technique of removing the uterus en bloc with the abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava, thereby allowing for a single cannulation site at the aorta for perfusion of both uterine arteries and both ovarian arteries. A number of studies (17 studies) removed the uterus after euthanasia, most commonly in the setting of sourcing research animals from slaughterhouses.

FIGURE 2

Comparative uterine anatomy. (A) Anatomy of the human uterus. (B) Anatomy of the swine uterus. (C) Blood supply to the uterus and ovaries, analogous across species.

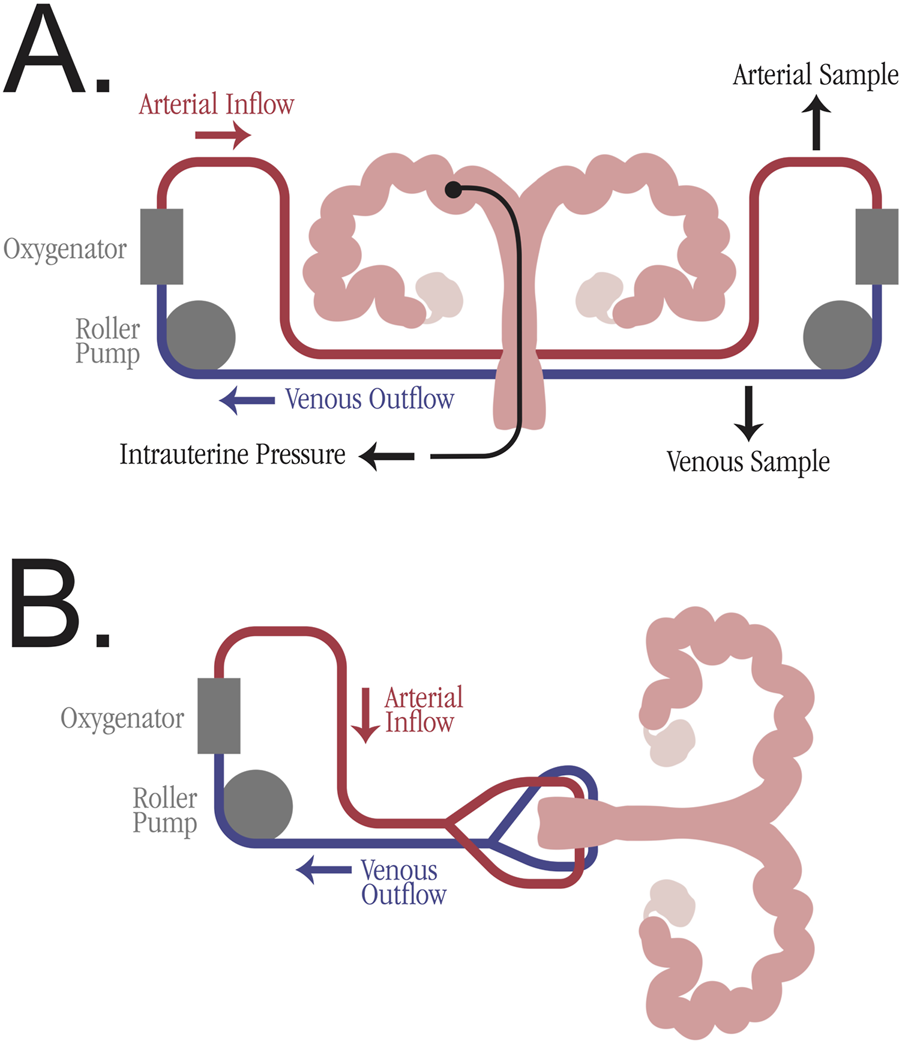

Perfusion Machine Design

The bilateral blood supply of the uterus poses a challenge for traditional machine perfusion devices, which typically have a single arterial inflow and single venous outflow. While some studies utilized a Y-connector after a single perfusion pump (6 studies), the majority of studies employed two separate pumps (21 studies), enabling adjustments to each artery individually and preventing unequal flow (see Figure 3). The studies cannulating the aorta all used a single pump for perfusion. All studies employed oxygenation of the perfusate, with the majority (28 studies) using carbogen gas. The perfusate medium was blood-based in 6 studies, but the majority of studies employed various organ preservation solutions, including Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer, Krebs-Henseleit buffer, and UW solution. Multiple studies utilized perfusate additives, including heparin, antibiotics, and insulin. The duration of the perfusions varied, with 11 studies perfusing for 1–6 h, 11 studies perfusing for 6–12 h, and 10 studies perfusing for more than 12 h. The longest perfusion was 52 h, utilizing a non-blood-based perfusate [32].

FIGURE 3

Simplified perfusion machine diagrams for uterus machine perfusion. (A) Individual arteriovenous circulation model with two roller pumps and oxygenator. Potential sampling venues are marked, including arterial perfusate sample, venous perfusate sample, and intrauterine pressure sample. (B) Mixed arteriovenous circulation model with one roller pump and a Y-connector for division of perfusate into bilateral uterine arteries.

As in solid organ machine perfusion, there is no consensus for the optimal temperature of uterus EVMP. As the majority of studies were not focused on storage or transplantation, most studies (28 studies) employed normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) (37 °C–39 °C) to mimic physiologic conditions. Three recent studies on uterine transplant preservation analyzed hypothermic machine perfusion (HMP) (4 °C) [53, 54, 56], and a fourth recent study on preservation analyzed sub-normothermic machine perfusion (SNMP) (20 °C) [55].

Flow and pressure varied greatly among studies that reported these values. These studies encompass perfusion of uteri from both humans and a variety of large animal models, thereby representing a wide range of uterine sizes. However, many studies (16 studies) employed normotensive or near-normotensive pressures (approximately 80–120 mmHg). Three recent studies [54–56], all in swine and all focused on transplant preservation, utilized much lower pressures (15–35 mmHg), aiming to mimic the low pressures employed in pancreas machine perfusion.

Graft Monitoring

In addition to flow, pressure, and temperature monitoring, there are multiple methods for assessing the uterine graft during and after machine perfusion. The majority of studies (24 studies) collected perfusate samples for chemistry and gas analysis, looking at changes in pH, pCO2, pO2, bicarbonate, potassium, and lactate over time. Many studies calculated change in uterine weight to assess edema during perfusion. The structural integrity of the uterus was assessed through various methods, including uterine biopsy, macroscopic appearance of the graft, and post-perfusion angiography. Multiple studies also utilized methods to assess the functional status of the organ, most commonly with the measurement of intrauterine pressure, but also through electromyography of the uterine muscle. Intrauterine pressure catheters allowed for the measurement and calculation of uterine contractions, many of which were induced artificially by the addition of oxytocin or prostaglandins.

Discussion

Surgical Model

The uterus poses unique challenges in the implementation of successful EVMP, especially in preclinical animal models. While the swine uterus was the most common animal model utilized, the anatomy is not identical to humans (see Figure 2). Furthermore, animal size and age both influence the uterine graft size and therefore the caliber of the arteries cannulated. Studies utilizing larger animals such as cows, or animals which had previously given birth, reported cannulating the uterine arteries with 14G or 16G catheters. Other studies which used 6 to 18-month-old swine reported uterine artery cannulation with catheters as small as 24G. Swine do not typically start to sexually mature until at least 7–8 months of age [58], so the use of younger swine further limits the uterine size. The one study to utilize a small animal model cannulated the aorta of the rabbit, presumably due to the uterine arteries being too small to cannulate. Even if cannulated, small-caliber arteries may not be amenable to successful anastomosis during subsequent transplantation, especially with the multiple vessel anastomoses required for uterine transplant. Therefore, animal size and age should be taken into serious consideration when choosing a model species.

One method for circumventing the surgical challenge of small-caliber arteries and multiple transplant anastomoses is to remove the uterus en bloc and cannulate via the aorta, which is described in three recent studies [53, 54, 56]. This technique has been previously described in preclinical uterine transplant models [58, 59]. In addition to reducing the anastomosis and cannulation site to a single large-caliber artery, this technique also incorporates the bilateral ovarian arteries and veins, which are often excluded from uterine EVMP models. However, this technique is surgically challenging, requiring the skeletonization of the aorta and its bifurcation, the inferior vena cava (IVC) and bifurcation, and the bilateral iliac vessels. All non-utero-ovarian branches from the infrarenal aorta, infrarenal IVC, and bilateral internal iliac vessels must be identified and ligated. The rectum or sigmoid colon must be transected in order to remove the uterine blood supply en bloc. The studies utilizing this model flushed the uterus with cold preservation solution retrograde through an external iliac artery (while clamping the infrarenal aorta), prior to definitive dissection of the uterine vessels. The reason for this is twofold: to minimize warm ischemia time during a lengthy dissection, and to mimic human deceased donor uterine procurements, in which the uterus is removed after all other essential organs are procured. Overall, this method for uterine procurement can be beneficial, especially if working with a smaller or younger animal model, but it requires an experienced surgical team and complex anatomical knowledge. This method is also limited to being performed as a terminal procedure and allotransplant model, preventing the utilization of an autotransplant model.

Optimal Perfusion Protocol

Given the breadth of variables involved in EVMP, it is difficult to devise an optimal perfusion protocol. Among VCA EVMP, there is no consensus on temperature or perfusate composition, although multiple studies have shown its benefit when compared to SCS [34, 60]. However, synthesis of the reviewed studies can identify some best practices for implementing EVMP in a uterine graft. The use of two perfusion pumps with individual pressure and flow adjustments is preferable to a single pump with a Y-connector (see Figure 3). This dual-pump system prevents unequal flow in the bilateral arteries due to variable pressure gradients [55]. In addition to oxygenation with carbogen, a perfusion medium should be prepared containing an organ preservation solution. While some studies added autologous whole blood to the perfusion medium, this may be impractical in clinical translation for a multi-organ deceased donor procurement.

The goal perfusion pressure varied between studies. The majority of large animal non-uterine VCA perfusions utilize normotensive pressures (60–80 mmHg) [34, 60], and many of the reviewed uterine studies reported similar goal pressures. However, three recent swine studies [54–56] utilized lower pressures (15–35 mmHg), citing the small caliber of the vessels and modeling the protocol after pancreas machine perfusion. Further research is needed to determine the optimal perfusion pressure, which likely will depend on animal size and vessel caliber.

As in solid organ EVMP, there is no consensus for optimal perfusion temperature in non-uterine VCA EVMP [15, 34, 60]. The articles reviewed in this paper predominantly utilize NMP, as many are using EVMP to model physiologic conditions rather than as a preservation method. Additional research into uterine HMP and SNMP is required to determine if lower temperatures are beneficial for uterine graft preservation.

Advantages and Limitations of Ex-Vivo Machine Perfusion in Uterus Transplantation

EVMP offers several potential advantages over static cold storage in the context of uterus transplantation. First, it may provide prolonged preservation times beyond those available through cold storage [61]. EVMP is able to continuously monitor perfusion parameters, such as flow, pressure, and metabolic activity, which may provide valuable insight into the viability of grafts prior to transplantation [61, 62]. Furthermore, it provides a therapeutic platform that helps to attenuate ischemia-reperfusion injury by providing oxygenated perfusate and targeted pharmacological or immunomodulatory interventions during preservation [62]. By enabling real-time evaluation of perfusion dynamics, EVMP may support viability testing and help identify uterine grafts with the greatest likelihood of successful transplantation.

Although EVMP has demonstrated promising results for solid organ preservation, the supporting evidence for its use in uterus transplantation remains preliminary because most studies have been conducted in animal models with limited human experience; therefore, its benefits for uterine preservation have not yet been conclusively determined. Perfusion systems, on the other hand, are expensive, technically complex, and require specialized knowledge [63]. In addition, perfusion itself may introduce risks, such as mechanical injury to delicate vascular endothelium or oxidative stress due to inadequate oxygenation [64].

Future Applications

As a whole, EVMP has the potential to not only prolong storage of uterine grafts, but also to optimize the graft itself. In solid organs, EVMP has been shown to recondition non-acceptable organs to be successfully transplanted [65, 66], thereby increasing organ availability and expanding the donor pool. The potential for extended storage times, organ optimization, and even immune engineering make EVMP a promising future technology for the practice of uterus transplantation.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This review is presented with the acknowledgement of several limitations. The literature search was conducted under the assumption that all relevant articles would be identifiable by the designated search terms and the databases utilized. Additionally, the review excluded abstracts, conference presentations, and unpublished data. There is a possibility that significant and noteworthy research on uterine EVMP was not included in the literature review, which might have allowed further insight into this topic.

Many of the articles discussed in this paper were published over 10 years ago. These studies did not have access to the most up-to-date protocols or designs of EVMP, especially as this is a rapidly-evolving technology. Therefore, the methods discussed in these articles may be outdated and not applicable to modern uterine transplantation practices. Only four articles, all published within the past 6 years, looked at EVMP as a method for transplant preservation. This small sample size makes it difficult to generalize and translate the studies into clinical practice. More studies on EVMP as a preservation method, especially HMP and SNMP, are needed to further research on this topic.

Despite its potential benefits, questions remain regarding the definitive effects of EVMP on uterus transplantation. In contrast to all other organs, uterine transplants are temporary, with hysterectomies performed after the birth of one or two children. Therefore, the improved long-term graft function associated with EVMP may be of lesser significance for the uterus. Additionally, no studies discussed in this paper are able to model or assess the true functionality of the uterus: embryo implantation and the ability to carry a pregnancy to term. Myometrial function is not analogous to endometrial function, and without adequate modeling of the functionality of the endometrium, no definitive conclusions can be made regarding the benefits of EVMP. Future preclinical studies involving embryo implantation and fetal development are necessary to determine the significance of EVMP for uterine transplant.

Conclusion

Ex-vivo machine perfusion is a versatile modality with the potential to preserve and optimize uterine grafts prior to transplantation. While many of the studies on uterine EVMP have been unrelated to preservation or transplantation, historical protocols can be used to inform future perfusions, in terms of surgical technique, perfusion machine design, perfusate composition, and graft monitoring. Further preclinical studies are needed to determine optimal perfusion protocols, to model endometrial function, and to definitively show a benefit to EVMP as compared to the current standard of SCS.

Statements

Author contributions

ED study conceptualization, manuscript writing, literature review, data analysis. SK manuscript writing, literature review, manuscript review. AL literature review, manuscript review. NL literature review, manuscript review. LJ literature review, manuscript review. BO study conceptualization, literature review, manuscript review. GB study conceptualization, literature review, manuscript review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

References

1.

Hur C Rehmer J Flyckt R Falcone T . Uterine Factor Infertility: A Clinical Review. Clin Obstet Gynecol (2019) 62(2):257–70. 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000448

2.

Johannesson L Testa G da Graca B Wall A . How Surgical Research Gave Birth to a New Clinical Surgical Field: A Viewpoint from the Dallas Uterus Transplant Study. Eur Surg Res Eur Chir Forsch Rech Chir Eur (2023) 64(2):158–68. 10.1159/000528989

3.

Fageeh W Raffa H Jabbad H Marzouki A . Transplantation of the Human Uterus. Int J Gynaecol Obstet Off Organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet (2002) 76(3):245–51. 10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00597-5

4.

Brännström M Johannesson L Bokström H Kvarnström N Mölne J Dahm-Kähler P et al Livebirth After Uterus Transplantation. Lancet Lond Engl (2015) 385(9968):607–16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61728-1

5.

Johannesson L Richards E Reddy V Walter J Olthoff K Quintini C et al The First 5 Years of Uterus Transplant in the US: A Report from the United States Uterus Transplant Consortium. JAMA Surg (2022) 157(9):790–7. 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.2612

6.

Brännström M Tullius SG Brucker S Dahm-Kähler P Flyckt R Kisu I et al Registry of the International Society of Uterus Transplantation: First Report. Transplantation (2023) 107(1):10–7. 10.1097/TP.0000000000004286

7.

Padma AM Truong M Jar-Allah T Song MJ Oltean M Brännström M et al The Development of an Extended Normothermic Ex Vivo Reperfusion Model of the Sheep Uterus to Evaluate Organ Quality After Cold Ischemia in Relation to Uterus Transplantation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand (2019) 98(9):1127–38. 10.1111/aogs.13617

8.

Wranning CA Mölne J El-Akouri RR Kurlberg G Brännström M . Short-Term Ischaemic Storage of Human Uterine myometrium--Basic Studies Towards Uterine Transplantation. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl (2005) 20(10):2736–44. 10.1093/humrep/dei125

9.

Tricard J Ponsonnard S Tholance Y Mesturoux L Lachatre D Couquet C et al Uterus Tolerance to Extended Cold Ischemic Storage After Auto-Transplantation in Ewes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol (2017) 214:162–7. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.05.013

10.

Tardieu A Dion L Lavoué V Chazelas P Marquet P Piver P et al The Key Role of Warm and Cold Ischemia in Uterus Transplantation: A Review. J Clin Med (2019) 8(6):760. 10.3390/jcm8060760

11.

Racho El-Akouri R Wranning CA Mölne J Kurlberg G Brännström M . Pregnancy in Transplanted Mouse Uterus After Long-Term Cold Ischaemic Preservation. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl (2003) 18(10):2024–30. 10.1093/humrep/deg395

12.

Gauthier T Piver P Pichon N Bibes R Guillaudeau A Piccardo A et al Uterus Retrieval Process From Brain Dead Donors. Fertil Steril (2014) 102(2):476–82. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.016

13.

Ejzenberg D Andraus W Baratelli Carelli Mendes LR Ducatti L Song A Tanigawa R et al Livebirth After Uterus Transplantation From a Deceased Donor in a Recipient With Uterine Infertility. Lancet Lond Engl (2019) 392(10165):2697–704. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31766-5

14.

Fronek J Janousek L Kristek J Chlupac J Pluta M Novotny R et al Live Birth Following Uterine Transplantation From a Nulliparous Deceased Donor. Transplantation (2021) 105(5):1077–81. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003346

15.

Tatum R O’Malley TJ Bodzin AS Tchantchaleishvili V . Machine Perfusion of Donor Organs for Transplantation. Artif Organs (2021) 45(7):682–95. 10.1111/aor.13894

16.

Guarrera JV Henry SD Samstein B Odeh-Ramadan R Kinkhabwala M Goldstein MJ et al Hypothermic Machine Preservation in Human Liver Transplantation: The First Clinical Series. Am J Transpl Off J Am Soc Transpl Am Soc Transpl Surg (2010) 10(2):372–81. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02932.x

17.

Peng P Ding Z He Y Zhang J Wang X Yang Z . Hypothermic Machine Perfusion Versus Static Cold Storage in Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Artif Organs (2019) 43(5):478–89. 10.1111/aor.13364

18.

Boncompagni E Gini E Ferrigno A Milanesi G Gringeri E Barni S et al Decreased Apoptosis in Fatty Livers Submitted to Subnormothermic Machine-Perfusion Respect to Cold Storage. Eur J Histochem EJH (2011) 55(4):e40. 10.4081/ejh.2011.e40

19.

Charlès L Filz von Reiterdank I Lancia HH Shamlou AA Berkane Y Rosales I et al Effect of Subnormothermic Machine Perfusion on the Preservation of Vascularized Composite Allografts After Prolonged Warm Ischemia. Transplantation (2024) 108(11):2222–32. 10.1097/TP.0000000000005035

20.

Markmann JF Abouljoud MS Ghobrial RM Bhati CS Pelletier SJ Lu AD et al Impact of Portable Normothermic Blood-Based Machine Perfusion on Outcomes of Liver Transplant: The OCS Liver PROTECT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg (2022) 157(3):189–98. 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.6781

21.

Roesel MJ Wiegmann B Ius F Knosalla C Iske J . The Role of Ex-Situ Perfusion for Thoracic Organs. Curr Opin Organ Transpl (2022) 27(5):466–73. 10.1097/MOT.0000000000001008

22.

Ghoneima AS Sousa Da Silva RX Gosteli MA Barlow AD Kron P . Outcomes of Kidney Perfusion Techniques in Transplantation from Deceased Donors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med (2023) 12(12):3871. 10.3390/jcm12123871

23.

Chakradhar A Mroueh J Talbot SG . Ischemia Time in Extremity Allotransplantation: A Comprehensive Review. Hand (N Y) (2024) 19:15589447241287806. 10.1177/15589447241287806

24.

Croome KP Barbas AS Whitson B Zarrinpar A Taner T Lo D et al American Society of Transplant Surgeons Recommendations on Best Practices in Donation After Circulatory Death Organ Procurement. Am J Transpl (2023) 23(2):171–9. 10.1016/j.ajt.2022.10.009

25.

Dickens BM . Legal and Ethical Issues of Uterus Transplantation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet (2016) 133(1):125–8. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.01.002

26.

Peirce EC Fuller EO Patton WW Swartwout JR Ballentine MB Wright BG et al Isolation Perfusion of the Pregnant Sheep Uterus. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs (1970) 16:318–24.

27.

Tojo S Sakai T Kanazawa S Mochizuki M . Perfusion of the Isolated Human Uterus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand (1972) 51(3):265–73. 10.3109/00016347209156857

28.

Bloch MH McLaughlin LL Martin SA Needleman P . Prostaglandin Production by the Pregnant and Non-Pregnant Rabbit Uterus. Prostaglandins (1983) 26(1):33–46. 10.1016/0090-6980(83)90072-2

29.

Richter ON Tschubel K Schmolling J Kupka M Ulrich U Wardelmann E . Immunohistochemical Reactivity of Myometrial Oxytocin Receptor in Extracorporeally Perfused Nonpregnant Human Uteri. Arch Gynecol Obstet (2003) 269(1):16–24. 10.1007/s00404-003-0474-0

30.

Bulletti C Jasonni VM Lubicz S Flamigni C Gurpide E . Extracorporeal Perfusion of the Human Uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol (1986) 154(3):683–8. 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90630-7

31.

Bulletti C Jasonni VM Martinelli G Govoni E Tabanelli S Ciotti PM et al A 48-hour Preservation of an Isolated Human Uterus: Endometrial Responses to Sex Steroids. Fertil Steril (1987) 47(1):122–9. 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)49947-4

32.

Bulletti C Jasonni VM Tabanelli S Gianaroli L Ciotti PM Ferraretti AP et al Early Human Pregnancy In Vitro Utilizing an Artificially Perfused Uterus. Fertil Steril (1988) 49(6):991–6. 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59949-x

33.

Bulletti C Jasonni VM Ciotti PM Tabanelli S Naldi S Flamigni C . Extraction of Estrogens by Human Perfused Uterus. Effects of Membrane Permeability and Binding by Serum Proteins on Differential Influx into Endometrium and Myometrium. Am J Obstet Gynecol (1988) 159(2):509–15. 10.1016/s0002-9378(88)80119-4

34.

Duru Ç Biniazan F Hadzimustafic N D'Elia A Shamoun V Haykal S . Review of Machine Perfusion Studies in Vascularized Composite Allotransplant Preservation. Front Transpl (2023) 2:1323387. 10.3389/frtra.2023.1323387

35.

Bulletti C Prefetto RA Bazzocchi G Romero R Mimmi P Polli V et al Electromechanical Activities of Human Uteri During Extra-corporeal Perfusion with Ovarian Steroids. Hum Reprod (1993) 8(10):1558–63. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137891

36.

Richter O Wardelmann E Dombrowski F Schneider C Kiel R Wilhelm K et al Extracorporeal Perfusion of the Human Uterus as an Experimental Model in Gynaecology and Reproductive Medicine. Hum Reprod (2000) 15(6):1235–40. 10.1093/humrep/15.6.1235

37.

Bäumer W Mertens A Braun M Kietzmann M . The Isolated Perfused Bovine Uterus as a Model for Mucous Membrane Irritation and Inflammation. ALTEX (2002) 19(2):57–63.

38.

Dittrich R Maltaris T Müller A Dragonas C Scalera F Beckmann MW . The Extracorporeal Perfusion of Swine Uterus as an Experimental Model: The Effect of Oxytocic Drugs. Horm Metab Res (2003) 35(9):517–22. 10.1055/s-2003-42651

39.

Richter ON Kübler K Schmolling J Kupka M Reinsberg J Ulrich U et al Oxytocin Receptor Gene Expression of estrogen-stimulated Human Myometrium in Extracorporeally Perfused Non-Pregnant Uteri. Mol Hum Reprod (2004) 10(5):339–46. 10.1093/molehr/gah039

40.

Braun M Kietzmann M . Ischaemia-Reperfusion Injury in the Isolated Haemoperfused Bovine Uterus: An In Vitro Model of Acute Inflammation. Altern Lab Anim (2004) 32(2):69–77. 10.1177/026119290403200204

41.

Maltaris T Dragonas C Hoffmann I Mueller A Schild RL Schmidt W et al The Extracorporeal Perfusion of the Swine Uterus as an Experimental Model: The Effect of Tocolytic Drugs. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol (2006) 126(1):56–62. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.07.026

42.

Mueller A Siemer J Schreiner S Koesztner H Hoffmann I Binder H et al Role of Estrogen and Progesterone in the Regulation of Uterine Peristalsis: Results From Perfused Non-pregnant Swine Uteri. Hum Reprod (2006) 21(7):1863–8. 10.1093/humrep/del056

43.

Mueller A Maltaris T Siemer J Binder H Hoffmann I Beckmann MW et al Uterine Contractility in Response to Different Prostaglandins: Results From Extracorporeally Perfused Non-Pregnant Swine Uteri. Hum Reprod (2006) 21(8):2000–5. 10.1093/humrep/del118

44.

Mueller A Siemer J Renner S Hoffmann I Maltaris T Binder H et al Perfused Non-Pregnant Swine Uteri: A Model for Evaluating Transport Mechanisms to the Side Bearing the Dominant Follicle in Humans. J Reprod Dev (2006) 52(5):617–24. 10.1262/jrd.18021

45.

Künzel J Geisler K Hoffmann I Müller A Beckmann MW Dittrich R . Myometrial Response to Neurotropic and Musculotropic Spasmolytic Drugs in an Extracorporeal Perfusion Model of Swine Uteri. Reprod Biomed Online (2011) 23(1):132–40. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.03.026

46.

Dittrich R Henning J Maltaris T Hoffmann I Oppelt PG Cupisti S et al Extracorporeal Perfusion of the Swine Uterus: Effect of Human Seminal Plasma. Andrologia (2012) 44(Suppl. 1):543–9. 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2011.01223.x

47.

Geisler K Künzel J Grundtner P Müller A Beckmann MW Dittrich R . The Perfused Swine Uterus Model: Long-Term Perfusion. Reprod Biol Endocrinol (2012) 10:110. 10.1186/1477-7827-10-110

48.

Künzel J Geisler K Maltaris T Müller A Hoffmann I Schneider H et al Effects of Interactions Between Progesterone and Prostaglandin on Uterine Contractility in a Perfused Swine Uterus Model. In Vivo (2014) 28(4):467–75.

49.

Stirland DL Nichols JW Jarboe E Adelman M Dassel M Janát-Amsbury MM et al Uterine Perfusion Model for Analyzing Barriers to Transport in Fibroids. J Control Release (2015) 214:85–93. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.07.006

50.

Oppelt PG Weber M Mueller A Boosz A Hoffmann I Raffel N et al Comparison of Dienogest and Progesterone Effects on Uterine Contractility in the Extracorporeal Perfusion Model of Swine Uteri. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand (2018) 97(11):1293–9. 10.1111/aogs.13428

51.

Weinschenk F Dittrich R Müller A Lotz L Beckmann MW Weinschenk SW . Uterine Contractility Changes in a Perfused Swine Uterus Model Induced by Local Anesthetics Procaine, Lidocaine, and Ropivacaine. PLoS One (2018) 13(12):e0206053. 10.1371/journal.pone.0206053

52.

Köhne M Unruh C Böttcher D Tönissen A Ulrich R Sieme H . Evaluation of an Ex Vivo Model of the blood-perfused Equine Uterus. Theriogenology (2022) 184:82–91. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2022.02.026

53.

Dion L Sousa C Boudjema K Val-Laillet D Jaillard S Rioux-Leclercq N et al Hypothermic Machine Perfusion for Uterus Transplantation. Fertil Steril (2023) 120(6):1259–61. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.08.020

54.

Loiseau E Mesnard B Bruneau S De Sousa C Bernardet S Hervouet J et al Uterine Transplant Optimization from a Preclinical Donor Model With Controlled Cardiocirculatory Arrest. Transpl Direct (2024) 11(1):e1735. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001735

55.

Cabanel L Oubari H Dion L Lavoué V Randolph MA Cetrulo CL et al Establishing a Swine Model to Study Uterus Dynamic Preservation and Transplantation. J Vis Exp (2024) 214. 10.3791/67357

56.

Sousa CH Mercier M Rioux-Leclercq N Flecher E Bendavid C Val-Laillet D et al Hypothermic Machine Perfusion in Uterus Transplantation in a Porcine Model: A Proof of Concept and the First Results in Graft Preservation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand (2025) 104(3):461–73. 10.1111/aogs.15056

57.

Johannesson L Testa G Flyckt R Farrell R Quintini C Wall A et al Guidelines for Standardized Nomenclature and Reporting in Uterus Transplantation: An Opinion From the United States Uterus Transplant Consortium. Am J Transpl (2020) 20(12):3319–25. 10.1111/ajt.15973

58.

Avison DL DeFaria W Tryphonopoulos P Tekin A Attia GR Takahashi H et al Heterotopic Uterus Transplantation in a Swine Model. Transplantation (2009) 88(4):465–9. 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b07666

59.

Brännström M Diaz-Garcia C Hanafy A Olausson M Tzakis A . Uterus Transplantation: Animal Research and Human Possibilities. Fertil Steril (2012) 97(6):1269–76. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.04.001

60.

Muss TE Loftin AH Zamore ZH Drivas EM Guo YN Zhang Y et al A Guide to the Implementation and Design of Ex Vivo Perfusion Machines for Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open (2024) 12(11):e6271. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000006271

61.

Del Prete L Cazzaniga B Liu Q Diago-Uso T Hashimoto K Quintini C. et al The Concept of Machine Perfusion in Uterus Transplantation. Eur J Transpl (2023) 155–62. 10.57603/ejt-018

62.

Xu J Buchwald JE Martins PN . Review of Current Machine Perfusion Therapeutics for Organ Preservation. Transplantation (2020) 104(9):1792–803. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003295

63.

Gao Q Alderete IS Aykun N Samy KP Nauser CL Raigani S et al Transforming the Logistics of Liver Transplantation with Normothermic Machine Perfusion: Clinical Impact Versus Cost. Liver Transpl (2025) 31(6):750–61. 10.1097/LVT.0000000000000560

64.

Hofmann J Pühringer M Steinkellner S Holl AS Meszaros AT Schneeberger S et al Novel, Innovative Models to Study Ischemia/reperfusion-related Redox Damage in Organ Transplantation. Antioxidants (Basel) (2022) 12(1):31. 10.3390/antiox12010031

65.

Urban M Bishawi M Castleberry AW Markin NW Chacon MM Um JY et al Novel Use of Mobile Ex-Vivo Lung Perfusion in Donation After Circulatory Death Lung Transplantation. Prog Transpl (2022) 32(2):190–1. 10.1177/15269248221087437

66.

Steen S Ingemansson R Eriksson L Pierre L Algotsson L Wierup P et al First Human Transplantation of a Nonacceptable Donor Lung After Reconditioning Ex Vivo. Ann Thorac Surg (2007) 83(6):2191–4. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.01.033

Summary

Keywords

uterus transplantation, machine perfusion, machine preservation, ex vivo perfusion, vascularized composite allotransplantation

Citation

Drivas EM, Khaki S, Loftin AH, Lamsehchi N, Johannesson L, Oh BC and Brandacher G (2025) A Comprehensive Review of Ex-Vivo Machine Perfusion in Uterus Transplantation. Transpl. Int. 38:15254. doi: 10.3389/ti.2025.15254

Received

11 July 2025

Revised

19 November 2025

Accepted

25 November 2025

Published

08 December 2025

Volume

38 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Drivas, Khaki, Loftin, Lamsehchi, Johannesson, Oh and Brandacher.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gerald Brandacher, brandacher@jhmi.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.