Abstract

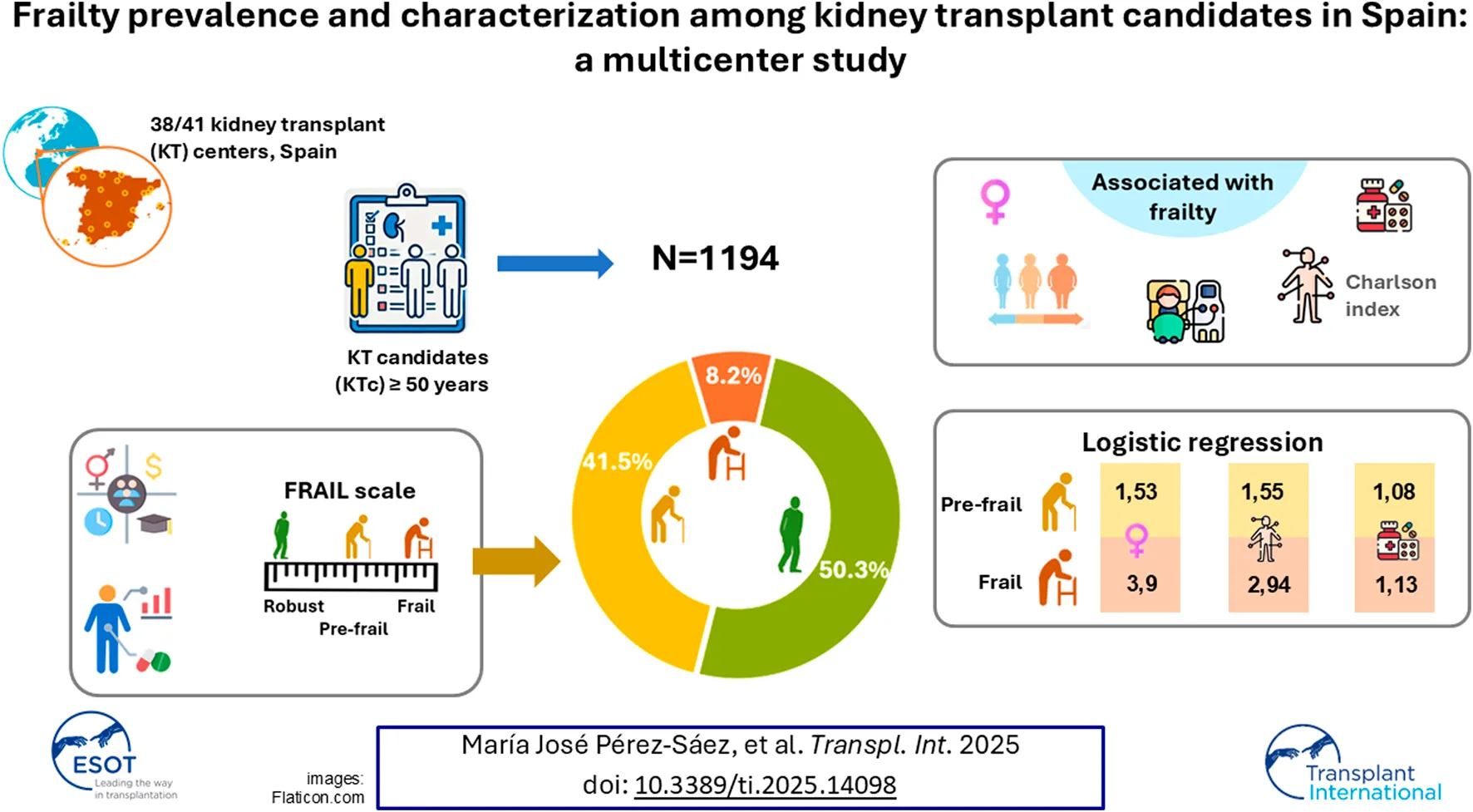

Frailty is a frequent condition among kidney transplant candidates (KTc) that confers poor outcomes after transplantation. We aimed to establish frailty prevalence in a representative sample of KTc in Spain. We conducted a multicenter cross-sectional study including 1194 KTc ≥50 years. Frailty was assessed by the FRAIL scale. Mean age was 64.2 years; 38.4% were female. Median Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was 6 [4–7] and the total number of medications was 9 [7–12]. We found that 8.2% of patients were frail and 41.5% were pre-frail. Frailty was more frequent among females (60.2% of frail vs. 32.8% of robust; p < 0.001), hemodialysis patients (74.5% of frail vs. 67.1% of robust; p = 0.02), and those with a high burden of disease (54.6% of frail patients with CCI >6 vs. 29.3% of robust; p < 0.001). The multivariable analysis confirmed that frailty was associated with the female sex (OR 3.9 [2.5–6.2]); higher CCI (>6 OR 2.9 [1.6–54]); and the number of medications (OR –per medication- 1.13 [1.07–1.2]). Almost 50% of KTc in Spain are pre-frail or frail. Frailty is more prevalent between women and patients with high comorbidity burden. Identifying those candidates at risk is essential to establish risks and implement strategies to minimize them.

Introduction

Frailty is characterized by a reduced physiological reserve to stressors and was initially studied within the aging population residing in communities [1]. Among individuals with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD), frailty is a frequent condition and has been reported to affect up to 70% of patients receiving hemodialysis [2, 3]. These patients experience poorer outcomes while on dialysis, including higher mortality rates [4, 5].

Frail CKD patients have also restricted access to the kidney transplantation (KT) waiting list and their chances of receiving a transplant are notably reduced [6, 7]. Among subjects evaluated for KT, frailty prevalence ranges from 5% to more than 50%, depending on the series and the scale used [6–9]. Eventually, pooled analysis of different studies shows that about 17% of KT recipients are identified as frail [10]. However, most of the studies included in the systematic reviews of frailty among KT recipients come from US cohorts, with a very small representation of European studies [11]. Sociodemographic differences between American and European populations prevent direct extrapolation of the results.

Frail KT recipients experience heightened rates of complications such as intolerance to immunosuppressants [12], prolonged length of stay and a higher rate of readmissions [13, 14], higher rate of delayed graft function and surgical complications [15, 16], and, more importantly, higher post-transplant mortality [14, 17–21].

In Spain, fewer than 20% of dialysis patients have access to KT [22]. Possibly, frailty hampers this access, especially among elderly recipients. Despite the recognized impact of frailty on KT outcomes, clinicians often encounter challenges in assessing frailty during outpatient visits, and questions arise regarding the best scale to use and the potential utility of the information obtained [23]. A survey across 133 KT programs in the US revealed that 69% of centers reported performing standardized frailty assessments during transplant evaluations, yet there was little consensus on the preferred tool for measuring frailty [24]. The scale proposed by Linda Fried more than 20 years ago, the Physical Frailty Phenotype (PFP), has emerged as the most used frailty scale in research involving KT candidates and recipients [1]. However, other less time-consuming metrics, like the FRAIL scale, have also found utility in this context [7, 25]. Centers conducting frailty evaluations through validated tools have demonstrated better waitlist and transplant outcomes, regardless of the tool used [26]. Although correlation among different frailty metrics is poor [27–29], identifying patients at risk for unfavorable results holds paramount importance in assessing prognosis, establishing preventive strategies, and implementing therapeutic interventions such as prehabilitation.

This is a multicenter cross-sectional study carried out with the participation of the vast majority of KT Units in Spain. We aimed to establish frailty prevalence and associated factors among KT candidates over 50 years in our setting, as well as to boost the universal implementation of the frailty measurement as part of the KT candidacy study work-up.

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This is a multicenter, cross-sectional study carried out in 38 KT Units in Spain during 2022.

All KT Units in Spain were invited to participate and 38 out of 41 agreed. During the outpatient visits, subjects ≥50 years old included on the KT waiting list and able to consent were invited to participate in the study. Both patients already included on the waiting list and those who were new inclusions during the visit could be included in the study. Patients with a major psychiatric disorder, cognitive impairment, or an acute condition that to the judgment of the investigator could cause a physical impairment were excluded from the study.

The study started in March 2022 and the inclusion was competitive among centers until the end of the study (December 2022). The number of patients included was different across centers, depending on the number of patients included on their KT waiting list, the frequency of the visits, etc. Although there were differences, with a maximum of 169 and a minimum of 2 patients per center, 50% centers included more than 20 patients in the study.

Clinical and epidemiological variables and the FRAIL scale were collected at each center and introduced in a central database. Data extraction and analysis were further conducted.

Ethics

The Institutional Review Board of Hospital del Mar approved the study (2020/9349), and all enrolled participants provided written informed consent at the time of frailty evaluation. The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, only relying on the official database.

Frailty Assessment

Frailty was assessed according to the FRAIL scale which includes 5 questions (all of them self-reported) assessing fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illness, and loss of weight. In both scales, each component or question scores 0/1 depending on its presence or absence. Robust patients were defined by a score of 0, pre-frail as those who ranked 1–2, and frail patients were defined by a score ≥3 [30].

The FRAIL scale has been proposed as a screening tool for frailty in general population [31]. It has been used in Spanish geriatric population [32] but also in Spanish KT candidates [7, 28].

Study Variables

Besides the FRAIL scale, we included demographics (age, sex, ethnicity); social (education -defined by 4 categories: elementary, primary education, secondary education, and tertiary education-, family or social support –living by their own, in family, with friends, in a health/social facility-); and clinical data (body mass index (BMI), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [33], total number of medications, cause of renal disease, type of renal replacement therapy (RRT), date of dialysis initiation and date of waiting list inclusion, candidate to re-transplantation, albumin levels, C-reactive protein levels).

Statistics

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), or median and interquartile range (IQR), according to normal distribution. Categorical data were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. Comparisons of baseline characteristics between two groups were made using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests to analyze categorical variables, Student’s t-test for continuous variables with normal distribution, and Mann–Whitney test for non-parametric variables. When three categories were present, the Chi-square test was also used to compare categorical variables, the ANOVA test to compare quantitative variables with normal distribution, and the Kruskal-Wallis test for quantitative variables without normal distribution. Binomial and multinomial logistic regression models considering frailty as yes/no (merging pre-frailty and frailty status) or with the three categories (robust, pre-frail, and frail) were conducted. Variables were considered to be included in the multinomial model if a p-value ≤0.20 was found in the bivariate analysis. Two multinominal logistic regression models were conducted: one including the global CCI (ranking 0–24), and other including only cardiovascular disease as Charlson comorbidities (ranking 0 to 4: myocardial infarction, congestive heart disease, peripheral vascular disease and cerebrovascular disease). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 29 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total number of 1194 KT candidates ≥50 years old were included in the study. Table 1 displays the main characteristics of the cohort. The mean age was 64.2 years, 38.4% of them were female and 92.7% were Caucasian. In terms of education and social support, 17.4% declared themselves as having received elementary education and 11.7% lived on their own. The most frequent cause of CKD was unknown (23.9%) followed by glomerular disease (19.5%). Almost one-third of candidates had received at least one kidney transplant before (27.6%). In terms of RRT modality, 64.9% were on hemodialysis, 18% were on peritoneal dialysis and 19.8% were on a situation of advanced CKD pre-dialysis. The median time from dialysis onset to the waiting list entry was 12 months. KT candidates presented with a high comorbidity burden (CCI >6) in 35.6% of the cases. Subsequently, the total number of medications prescribed to each patient was high (9). In terms of laboratory parameters, mean albumin levels were 4 g/dL and mean levels of C-reactive protein were 0.6 mg/dL.

TABLE 1

| KT candidates (n = 1,194) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± sd) *n = 0, 0% | 64.2 ± 8.4 |

| Sex (female, n (%)) *n = 0, 0% | 459 (38.4) |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian, n (%)) *n = 9, 0.8% | 1,107 (92.7) |

| Education (elementary, n (%)) *n = 170, 14.2% | 208 (17.4) |

| Family/social support (living alone, (%)) *n = 84, 7% | 140 (11.7) |

| BMI (Kg/m2, mean ± sd) *n = 79, 6.6% | 26.7 ± 4.5 |

| Cause of renal disease *n = 5, 0.4% Unknown Diabetic nephropathy Glomerular disease Others | 285 (23.9) 183 (15.3) 233 (19.5) 493 (41.3) |

| Previous KT (yes, n, (%)) *n = 14, 1.2% Number of previous KT (median [max-min]) | 329 (27.6) 1 [1–5] |

| Renal replacement therapy modality (n, (%)) *n = 3, 0.3% Hemodialysis Peritoneal dialysis Preemptive transplant | 775 (64.9) 215 (18) 201 (19.8) |

| Time from dialysis onset to WL entry (years, median [IQR]) *n= 291, 24.7% Time from dialysis onset to frailty determination (years, median [IQR]) *n = 0, 0% | 1 [0.5–1.9] 2 [1–3.9] |

| Charlson comorbidity index (median [IQR]) *n = 18, 1.5% Low comorbidity = 3–4 Intermediate comorbidity = 5–6 High comorbidity >6 | 6 [4–7] 337 (28.7) 420 (35.7) 419 (35.6) |

| Total number of different medications (median [IQR]) *n = 0, 0% | 9 [7–12] |

| Albumin (g/dL, mean ± sd) *n = 200, 16.7% | 4 ± 0.6 |

| CRP (mg/dL, median [IQR]) *n = 370, 31% | 0.6 [0.2–1.9] |

Baseline and clinical characteristics of the 1194 KT candidates included in the study.

KT, kidney transplant; sd, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; WL, waiting list; CRP, C-reactive protein. *Frequencies and % of missing data of each variable.

Frailty prevalence was determined by the FRAIL scale. Half of the patients were robust (50.3%), 41.5% were pre-frail, and 8.2% were frail. The most frequently reported item was fatigue (27.7%), followed by loss of weight (21.1%) and lack of robustness (15.5%). Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Table 2 compares KT candidates who were robust, pre-frail, and frail. We found a higher percentage of females as the frail score increases (32.8% of robust patients; 40.9% of pre-frail; and 60.2% of frail patients). Frail candidates were also slightly more overweighted (BMI 27.5 kg/m2 in frail candidates vs. 26.1 kg/m2 in robust ones), were more frequently receiving hemodialysis as RRT (74.5% -frail- vs. 67.1% -robust-), had higher comorbidity burden (CCI >6 54.6% -frail- vs. 29.3% -robust-), and were on more medications (11 –frail- vs. 8.5 –robust-). On the contrary, the mean age was similar among robust and frail candidates. No differences in terms of albumin or C-reactive protein levels were found between robust or frail patients either.

TABLE 2

| Baseline and clinical characteristics of KT candidates | Robust group | Pre-frail group | Frail group | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRAIL = 0 (n = 600) | FRAIL = 1–2 (n = 496) | FRAIL ≥3 (n = 98) | ||

| Age (years, mean ± sd) | 64.1 ± 8.2 | 64.5 ± 8.7 | 63.3 ± 8.1 | 0.475 |

| Sex (female, n (%)) | 197 (32.8) | 203 (40.9) | 59 (60.2) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian, n (%)) | 553 (93.3) | 464 (93.9) | 90 (91.8) | 0.729 |

| Education (basic, n (%)) | 99 (19.4) | 87 (20.3) | 22 (26.2) | 0.093 |

| Family/social support (living alone, (%)) | 70 (12.6) | 53 (11.4) | 17 (18.5) | 0.230 |

| BMI (Kg/m2, mean ± sd) | 26.1 ± 4.1 | 27.1 ± 4.6 | 27.5 ± 5.4 | 0.002 |

| Cause of renal disease Unknown Diabetic nephropathy Glomerular disease Others | 128 (21.5) 88 (14.8) 116 (19.5) 268 (44.6) | 129 (26.1) 79 (16) 98 (19.8) 190 (19.8) | 28 (28.6) 16 (16.3) 19 (19.4) 35 (35.7) | 0.734 |

| Previous KT (yes, n, (%)) Number of previous KT (median [max-min]) | 167 (28.1) 1 [1–3] | 129 (26.4) 1 [1–5] | 33 (34.4) 1 [1–3] | 0.276 0.993 |

| Renal replacement therapy modality (n, (%)) Hemodialysis Peritoneal dialysis Preemptive transplant | 402 (67.1) 106 (17.7) 91 (15.2) | 300 (60.7) 93 (18.8) 101 (20.4) | 73 (74.5) 16 (16.3) 9 (9.2) | 0.020 |

| Time from dialysis onset to WL entry (years, median [IQR]) Time from dialysis onset to frailty determination (years, median [IQR]) | 1.1 [0.6–2.3] 2 [1–3.8] | 1.2 [0.6–2.3] 1.8 [1–3.8] | 1.5 [0.7–4.1] 3 [1.-4.9] | 0.105 0.471 |

| Charlson comorbidity index Low comorbidity = 3–4 Intermediate comorbidity = 5–6 High comorbidity >6 | 195 (33.2) 221 (37.6) 172 (29.3) | 124 (25.3) 173 (35.2) 194 (39.5) | 18 (18.6) 26 (26.8) 53 (54.6) | <0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (only considering CV risk factors (0–4) Low comorbidity = 0 Intermediate comorbidity = 1 High comorbidity =2–4 | 394 (55.9) 138 (42.6) 56 (9.52) | 282 (40) 149 (46) 60 (12.2) | 29 (4.1) 37 (11.4) 31 (31.9) | <0.001 |

| Total number of different medications (median [IQR]) | 8.5 [7–11] | 10 [7–12] | 11 [8–13] | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL, mean ± sd) | 4 ± 0.6 | 4 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 0.688 |

| CRP (mg/dl, median [IQR]) | 0.6 [0.2–1.8] | 0.5 [0.2–1.7] | 1 [0.2–2.6] | 0.205 |

Baseline and clinical characteristics of KT candidates according to their FRAIL score.

KT, kidney transplant; sd, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; WL, waiting list; CV, cardiovascular; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Two multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to analyze factors associated with pre-frailty and frailty in KT candidates (Table 3). In the first model, including global Charlson index as comorbidity index, female sex (odds ratio (OR) 1.53 [1.19–1.98]), high comorbidity burden (OR 1.55 [1.13–2.13]), and total number of medications (OR 1.08 per medication [1.04–1.12]) were associated with pre-frailty status. The same factors with higher intensity were also associated with frailty: female sex (OR 3.90 [2.46–6.19]), high comorbidity burden (OR 2.93 [1.61–5.41]), and total number of medications (OR 1.13 per medication [1.07–1.20]), Table 3. The second model included only cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, congestive heart disease, peripheral vascular disease and cerebrovascular disease) as comorbidity burden. Cardiovascular disease was highly associated with frailty in this cohort, starting at one cardiovascular problem (OR 3.46 [2.02–5.95], and increasing this association along with the number of cardiovascular problems (Table 3).

TABLE 3

| Independent variables | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | |||

| Pre-frailty (FRAIL = 1–2) | |||

| Sex (ref: male) | 1.531 | 1.186 | 1.978 |

| Charlson index (ref: 3–4) | |||

| 5–6 | 1.097 | 0.806 | 1.492 |

| >6 | 1.550 | 1.126 | 2.135 |

| Number of medications (per each one) | 1.081 | 1.045 | 1.118 |

| Frailty (FRAIL ≥3) | |||

| Sex (ref: male) | 3.904 | 2.462 | 6.190 |

| Charlson index (ref: 3–4) | |||

| 5–6 | 1.030 | 0.539 | 1.970 |

| >6 | 2.935 | 1.612 | 5.412 |

| Number of medications (per each one) | 1.132 | 1.067 | 1.200 |

| B | |||

| Pre-frailty (FRAIL = 1–2) | |||

| Sex (ref: male) | 1.504 | 1.166 | 1.941 |

| Charlson CV index (ref: 0) | |||

| 1 | 1.387 | 1.043 | 1.844 |

| 2 | 1.369 | 0.876 | 2.139 |

| 3 | 1.369 | 0.541 | 3.462 |

| 4 | 1.416 | 0.196 | 10.247 |

| Number of medications (per each one) | 1.084 | 1.049 | 1.122 |

| Frailty (FRAIL ≥3) | |||

| Sex (ref: male) | 4.117 | 2.572 | 6.591 |

| Charlson CV index (ref: 0) | |||

| 1 | 3.466 | 2.019 | 5.948 |

| 2 | 8.204 | 4.278 | 15.731 |

| 3 | 7.897 | 2.337 | 26.682 |

| 4 | 7.897 | 2.337 | 26.682 |

Multinomial logistic regression of factors associated with pre-frailty and frailty in KT candidates. A) Considering global Charslon index; B) Considering a cardiovascular Charlson index (0–4).

KT, kidney transplant; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

We initially explored factors associated with pre-frailty and frailty through a binomial logistic regression. Factors with a p-value <0.2 were included in the final multinomial analysis: A) age, sex, body mass index, level of education, renal replacement therapy modality, C-reactive protein levels, Charlson comorbidity index, and number of medications; B) age, sex, body mass index, level of education, renal replacement therapy modality, C-reactive protein levels, Charlson cardiovascular comorbidity index, and number of medications.

Discussion

Herein, we present a multicenter cross-sectional study involving thirty-eight out of the total forty-one Kidney Transplant Units in Spain and more than 1000 CKD patients who are KT candidates that establishes the prevalence of frailty according to the FRAIL scale and factors associated. This sample represents about 50% of all patients over 50 years included in the KT waiting list in Spain (data provided by Spanish National Transplant Organization). Although less than 10% of KT candidates ≥50 years old in Spain are frail, the prevalence of pre-frailty and frailty together was almost 50% of the cohort. Female sex, comorbidity, and medications were strongly associated with frailty status.

The prevalence of frailty among KT candidates already listed for transplantation may vary from less than 5% to more than 50%, depending on the population and the scale used [6–9]. A large multicenter study from the US identified 18% of individuals as frail at the time of initial evaluation, while only 12% of individuals were identified as being frail among those who were ultimately listed for KT [6]. Among KT recipients, frailty prevalence before transplantation was established at 17.1% when a pooled analysis was made [10]. However, eleven of the fourteen studies included in the analysis were from the US. In Europe, two single-center studies have explored the prevalence of frailty in KT candidates/recipients: 15% of KT recipients were frail according to the Groningen Frailty Indicator in a Dutch study [11], and 10.5% and 3.6% of KT candidates were frail according to the PFP and the FRAIL scale, respectively, in a Spanish study [7]. In this multicenter study, we describe a large cohort of Spanish KT candidates over 50 years listed for transplantation with a prevalence of frailty of 8.2% according to the FRAIL scale. Pre-frailty was a very frequent finding, with 41.5% of candidates scoring 1 or 2 points by FRAIL. This has relevance as not only frailty but also pre-frailty has been associated with poorer outcomes in patients after transplantation [20]. In our cohort, the most frequently reported item was fatigue, followed by loss of weight. The lack of robustness was present in 15.5% of the patients. The latter is especially relevant given that pre-transplant grip strength has been found to be the most important frailty item related to post-transplant outcomes [34].

Differences in frailty prevalence may respond to different scales applied. Although there is an agreement regarding the underlying conceptual framework of frailty, there is a low level of consensus regarding the constituent elements to be included in operational definitions of frailty [35]. Consequently, various frailty metrics, encompassing different aspects like physical reserve, morbidity, cognition, or social factors, have been developed to date [3]. The PFP remains the most popular one for KT candidates and recipients and is characterized by the presence of three out of five indicators: slow walking speed, low physical activity, unintentional weight loss, weakness, and exhaustion. It has been suggested as the preferred choice for measuring physical reserve [36]. In contrast, the FRAIL scale also requires 3 out of 5 criteria—weight loss, resistance, fatigue, ambulation, and illness—but all items are self-reported [25], and, therefore, easier and faster to apply in the clinical practice setting. On the other hand, as the FRAIL scale did not account for objective measurements of physical reserve, it might underestimate the presence of frailty and classify as robust a patient who can be pre-frail or frail [28]. The decision regarding which scale to utilize during candidate evaluation will hinge on various factors, including the scale’s feasibility concerning time and resource consumption. In any case, clinicians should opt for a validated frailty scale, as they have demonstrated better transplant outcomes [26]. In our study, the prevalence of frailty was lower than the reported in studies from the US (8.2% vs. 15%–20%). This may reflect population differences, but also scale-dependent differences, as FRAIL usually estimates a lower prevalence of frailty than others that include physical domains [28]. There is no clear consensus on what frailty tool should be used in this population, and no systematic determinations are held during KT candidates’ evaluation [37]. Reasons to choose one frailty tool over the rest are broad, and KT candidates lack of a specific frailty tool (in contrast to liver transplant candidates) [38]. We chose the FRAIL scale because at that time 90% of KT centers in Spain were not systematically measuring frailty in their KT candidates. FRAIL scale has been acknowledged as a validated screening tool for frailty and is very easy to implement [39]. Our aim was to dimension and highlight the problem of frailty, and we needed to establish the frailty prevalence with a tool that most of the centers were willing and able to do.

Despite being a geriatric syndrome, age was not related to frailty in KT candidates, similar to what other studies in the CKD population have found [2, 40, 41]. Additionally, this fact could be related to a more restrictive selection of older candidates included in the waiting list [42]. We did find that female sex and comorbidity/treatment are associated with frailty in our cohort of patients. The second one is foreseeable as the FRAIL scale accounts for disease as part of its frailty phenotype. Importantly, cardiovascular disease seems to play the leading role in this association. On the contrary, time on dialysis was not associated with frailty, despite frail patients presented with a substantial longer time on dialysis. Although patient’s functional status decline seem irreversible after starting dialysis, studies have reported improvement in frailty status in up to one third of patients after starting dialysis [43]. Regarding sex, studies in community-dwelling populations have revealed a higher prevalence of frailty in females compared to males [44]. Studies including liver and kidney transplant candidates have found similar results [40, 45]. However, although women present with more frailty than men do, health results in the general population are usually worse in the latter, known as the male-female health-survival paradox [44, 46]. In liver transplant candidates, however, women present with higher mortality rates on the waiting list [45], while female kidney transplant candidates have lower mortality rates than men [47, 48]. Moreover, not only the prevalence but also the components and characteristics of frailty differ between male and female frail patients [40]. Examining sex-based disparities in frailty holds the potential to enhance risk assessment before transplantation and tailor specific, personalized interventions. Regarding BMI and albumin levels, we did not find any association with frailty status in this cohort. This may reflect how poorly BMI and albumin levels detect potential sarcopenia in these patients. Conversely, a higher BMI was found among frail patients. As sarcopenia is defined as reduced muscle mass and strength, a higher BMI does not necessarily reflect less risk of sarcopenia [49]. Moreover, it has been described that albumin levels may not differ among robust and frail KT candidates but sarcopenia does [28]. Novel biomarkers should guide the future investigation in this regard [50].

Our study has limitations, as it is a cross-sectional study that analyzes frailty prevalence and factors associated, lacking a follow-up of the patients. Regarding the study design, it has a potential selection bias, as there were centers with a high number of patients included while others only included a few patients. In addition, the FRAIL scale has been proposed as a screening frailty tool [23, 31], and its sensitivity detecting CKD frail patients may be lower [7, 28, 39]. However, this is to our knowledge the largest cohort of European KT candidates with frailty measurement reported so far. We aimed to establish the dimensions of the frailty problem in the KT waiting list in Spain, using a representative cohort. More than 1,000 patients over 50 years have been analyzed, from a total (considering all ages) of 4000 individuals included in the KT waiting list in Spain by the end of 2023 [22]. We provide important information about the prevalence and factors associated with frailty that may serve to implement adequate preventive and treatment interventions in this population. The photograph of the situation might be also useful for changing health policies.

In conclusion, less than 10% of the KT waiting list in Spain is frail according to the FRAIL scale, but pre-frailty and frailty together account for half of the patients. Female sex and comorbidity burden are factors associated with frailty. As frailty has a negative impact on outcomes after transplantation, measurements to improve/revert frailty should be part of the healthcare and preparation of candidates for KT.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board of Hospital del Mar approved the study (2020/9349). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MP-S conducted the multicenter study, ran the analysis, and wrote the manuscript. AG-D and FM conceptualized the study and interpreted the results. RM, EME, and JZ supported and organized the study. The rest of the authors included patients in the study. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors declare that this study received funding from Sandoz Farmacéutica SA, Spain. The funder contributed to the study by providing financial support for data collection and statistical analysis, as well as participating in the preparation of the final English version of the manuscript. The funder had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflict of interest

Authors RM, EME, and JZ were employed by the company Sandoz Farmacéutica SA.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

References

1.

FriedLPTangenCMWalstonJNewmanABHirschCGottdienerJet alFrailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (2001) 56(3):146–M156. 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146

2.

BaoYDalrympleLChertowGMKaysenGAJohansenKL. Frailty, Dialysis Initiation, and Mortality in End-Stage Renal Disease. Arch Intern Med (2012) 172(14):1071–7. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3020

3.

HarhayMNRaoMKWoodsideKJJohansenKLLentineKLTulliusSGet alAn Overview of Frailty in Kidney Transplantation: Measurement, Management and Future Considerations. Nephrol Dial Transpl (2020) 35(7):1099–112. 10.1093/ndt/gfaa016

4.

JohansenKLChertowGMJinCKutnerNG. Significance of Frailty Among Dialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol (2007) 18(11):2960–7. 10.1681/ASN.2007020221

5.

McAdams-DemarcoMALawASalterMLBoyarskyBGimenezLJaarBGet alFrailty as a Novel Predictor of Mortality and Hospitalization in Individuals of All Ages Undergoing Hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc (2013) 61(6):896–901. 10.1111/jgs.12266

6.

HaugenCEChuNMYingHWarsameFHolscherCMDesaiNMet alFrailty and Access to Kidney Transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol (2019) 14(4):576–82. 10.2215/CJN.12921118

7.

Pérez-SáezMJRedondo-PachónDArias-CabralesCEFauraABachABuxedaAet alOutcomes of Frail Patients while Waiting for Kidney Transplantation: Differences between Physical Frailty Phenotype and FRAIL Scale. J Clin Med (2022) 11(3):672. 10.3390/JCM11030672

8.

HaugenCEAgoonsDChuNMLiyanageLLongJDesaiNMet alPhysical Impairment and Access to Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation (2020) 104(2):367–73. 10.1097/TP.0000000000002778

9.

HaugenCEThomasAGChuNMShafferAANormanSPBingamanAWet alPrevalence of Frailty Among Kidney Transplant Candidates and Recipients in the United States: Estimates from a National Registry and Multicenter Cohort Study. Am J Transpl (2020) 20(4):1170–80. 10.1111/ajt.15709

10.

QuintEEZogajDBanningLBDBenjamensSAnnemaCBakkerSJLet alFrailty and Kidney Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transpl Direct (2021) 7(6):E701. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001156

11.

SchopmeyerLEl MoumniMNieuwenhuijs-MoekeGJBergerSPBakkerSJLPolRA. Frailty Has a Significant Influence on Postoperative Complications after Kidney Transplantation—A Prospective Study on Short-Term Outcomes. Transpl Int (2019) 32(1):66–74. 10.1111/tri.13330

12.

McAdams-DemarcoMALawATanJDelpCKingEAOrandiBet alFrailty, Mycophenolate Reduction, and Graft Loss in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation (2015) 99(4):805–10. 10.1097/TP.0000000000000444

13.

GoldfarbDA. Re: Frailty and Early Hospital Readmission after Kidney Transplantation. J Urol (2014) 191(5):1366–7. 10.1016/j.juro.2014.02.016

14.

McAdams-DemarcoMAKingEALuoXHaugenCDiBritoSShafferAet alFrailty, Length of Stay, and Mortality in Kidney Transplant Recipients: A National Registry and Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Surg (2017) 266(6):1084–90. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002025

15.

Garonzik-WangJMGovindanPGrinnanJWLiuMAliHMChakrabortyAet alFrailty and Delayed Graft Function in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Arch Surg (2012) 147(2):190–3. 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1229

16.

MakaryMASegevDLPronovostPJSyinDBandeen-RocheKPatelPet alFrailty as a Predictor of Surgical Outcomes in Older Patients. J Am Coll Surg (2010) 210(6):901–8. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028

17.

McAdams-DeMarcoMAYingHOlorundareIKingEAHaugenCButaBet alIndividual Frailty Components and Mortality in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation (2017) 101(9):2126–32. 10.1097/TP.0000000000001546

18.

McAdams-DeMarcoMAChuNMSegevDL. Frailty and Long-Term Post-Kidney Transplant Outcomes. Curr Transpl Rep (2019) 6(1):45–51. 10.1007/s40472-019-0231-3

19.

McAdams-DemarcoMALawAKingEOrandiBSalterMGuptaNet alFrailty and Mortality in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Am J Transpl (2015) 15(1):149–54. 10.1111/ajt.12992

20.

Pérez-SáezMJArias-CabralesCERedondo-PachónDBurballaCBuxedaABachAet alIncreased Mortality after Kidney Transplantation in Mildly Frail Recipients. Clin Kidney J (2022) 15(11):2089–96. 10.1093/CKJ/SFAC159

21.

AlfieriCMalvicaSCesariMVettorettiSBenedettiMCiceroEet alFrailty in Kidney Transplantation: A Review on its Evaluation, Variation and Long-Term Impact. Clin Kidney J (2022) 15(11):2020–6. 10.1093/ckj/sfac149

22.

Actividad De Donación Y Trasplante Renal España. Organización Nacional de Trasplantes (2023).

23.

McAdams-DeMarcoMAThindAKNixonACWoywodtA. Frailty Assessment as Part of Transplant Listing: Yes, No or Maybe?Clin Kidney J (2022) 16(5):809–16. 10.1093/CKJ/SFAC277

24.

McAdams-DeMarcoMAVan Pilsum RasmussenSEChuNMAgoonsDParsonsRFAlhamadTet alPerceptions and Practices Regarding Frailty in Kidney Transplantation: Results of a National Survey. Transplantation (2020) 104(2):349–56. 10.1097/TP.0000000000002779

25.

MorleyJEMalmstromTKMillerDK. A Simple Frailty Questionnaire (FRAIL) Predicts Outcomes in Middle Aged African Americans. J Nutr Heal Aging (2012) 16(7):601–8. 10.1007/s12603-012-0084-2

26.

ChenXLiuYThompsonVChuNMKingEAWalstonJDet alTransplant Centers that Assess Frailty as Part of Clinical Practice Have Better Outcomes. BMC Geriatr (2022) 22(1):82–12. 10.1186/S12877-022-02777-2

27.

van LoonINGotoNABoereboomFTJBotsMLVerhaarMCHamakerME. Frailty Screening Tools for Elderly Patients Incident to Dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol (2017) 12(9):1480–8. 10.2215/CJN.11801116

28.

Pérez-SáezMJDávalos-YeroviVRedondo-PachónD. Frailty in Kidney Transplant Candidates: A Comparison between Physical Frailty Phenotype and FRAIL Scales. J Nephrol. 10.1007/s40620-021-01234-4

29.

MalmstromTKMillerDKMorleyJE. A Comparison of Four Frailty Models. J Am Geriatr Soc (2014) 62(4):721–6. 10.1111/JGS.12735

30.

MorleyJEVellasBAbellan van KanGAnkerSDBauerJMBernabeiRet alFrailty Consensus: A Call to Action. J Am Med Dir Assoc (2013) 14(6):392–7. 10.1016/J.JAMDA.2013.03.022

31.

HOW TO CHOOSE. How to Choose a Frailty Tool. Available online at: https://efrailty.hsl.harvard.edu/HowtoChoose.html (Accessed March 10, 2025).

32.

Oviedo-BrionesMLasoÁRCarniceroJACesariMGrodzickiTGryglewskaBet alA Comparison of Frailty Assessment Instruments in Different Clinical and Social Care Settings: The Frailtools Project. J Am Med Dir Assoc (2020) 22:607.e7–607.e12. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.024

33.

CharlsonMEPompeiPAlesKLMacKenzieCR. A New Method of Classifying Prognostic Comorbidity in Longitudinal Studies: Development and Validation. J Chronic Dis (1987) 40(5):373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

34.

ParajuliSAstorBCLordenHMO'TooleKAWallschlaegerREBreyerICet alAnalysis of Individual Components of Frailty: Pre-Transplant Grip Strength Is the Strongest Predictor of Post Kidney Transplant Outcomes. Clin Transpl (2022) 36(12):e14827. 10.1111/CTR.14827

35.

Rodríguez-MañasLFéartCMannGViñaJChatterjiSChodzko-ZajkoWet alSearching for an Operational Definition of Frailty: A Delphi Method Based Consensus Statement. The Frailty Operative Definition-Consensus Conference Project. Journals Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci (2013) 68(1):62–7. 10.1093/GERONA/GLS119

36.

Bandeen-RocheKGrossALVaradhanRButaBCarlsonMCHuisingh-ScheetzMet alPrinciples and Issues for Physical Frailty Measurement and its Clinical Application. Journals Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci (2020) 75(6):1107–12. 10.1093/GERONA/GLZ158

37.

LevinAAhmedSBCarreroJJFosterBFrancisAHallRKet alExecutive Summary of the KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease: Known Knowns and Known Unknowns. Kidney Int (2024) 105(4):684–701. 10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.016

38.

LaiJCCovinskyKEDodgeJLBoscardinWJSegevDLRobertsJPet alDevelopment of a Novel Frailty Index to Predict Mortality in Patients with End-Stage Liver Disease. Hepatology (2017) 66(2):564–74. 10.1002/HEP.29219

39.

Pérez-SáezMJPascualJ. Unmet Questions about Frailty in Kidney Transplant Candidates. Transplantation (2024). 10.1097/TP.0000000000005093

40.

Pérez-SáezMJArias-CabralesCEDávalos-YeroviVRedondoDFauraAVeraMet alFrailty Among Chronic Kidney Disease Patients on the Kidney Transplant Waiting List: The Sex-Frailty Paradox. Clin Kidney J (2021) 15(1):109–18. 10.1093/CKJ/SFAB133

41.

ChowdhuryRPeelNMKroschMHubbardRE. Frailty and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr (2017) 68:135–42. 10.1016/j.archger.2016.10.007

42.

BufordJRetzloffSWilkASMcPhersonLHardingJLPastanSOet alRace, Age, and Kidney Transplant Waitlisting Among Patients Receiving Incident Dialysis in the United States. Kidney Med (2023) 5(10):100706. 10.1016/J.XKME.2023.100706

43.

JohansenKL. Frailty Among Patients Receiving Hemodialysis: Evolution of Components and Associations with Mortality (2019). p. 1–31.

44.

GordonEHPeelNMSamantaMTheouOHowlettSEHubbardRE. Sex Differences in Frailty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Exp Gerontol (2017) 89:30–40. 10.1016/j.exger.2016.12.021

45.

LaiJCGangerDRVolkMLDodgeJLDunnMADuarte-RojoAet alAssociation of Frailty and Sex with Wait List Mortality in Liver Transplant Candidates in the Multicenter Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation (FrAILT) Study. JAMA Surg Published Online (2021) 156:256–62. 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5674

46.

OksuzyanAJuelKVaupelJWChristensenK. Men: Good Health and High Mortality. Sex Differences in Health and Aging. Aging Clin Exp Res (2008) 20(2):91–102. 10.1007/BF03324754

47.

LynchRJRebeccaZPatzerRELarsenCPAdamsAB. Waitlist Hospital Admissions Predict Resource Utilization and Survival after Renal Transplantation. Ann Surg (2016) 264(6):1168–73. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001574

48.

LynchRJZhangRPatzerRELarsenCPAdamsAB. First-Year Waitlist Hospitalization and Subsequent Waitlist and Transplant Outcome. Am J Transpl (2017) 17(4):1031–41. 10.1111/ajt.14061

49.

CurtisMSwanLFoxRWartersAO’SullivanM. Associations between Body Mass Index and Probable Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Nutrients (2023) 15(6):1505. 10.3390/NU15061505

50.

Madrid-GambinFPérez-SáezMJGómez-GómezAHaroNRedondo-PachónDDávalos-YeroviVet alFrailty and Sarcopenia Metabolomic Signatures in Kidney Transplant Candidates: The FRAILMar Study. Clin Kidney J (2025) 18(1):366. 10.1093/CKJ/SFAE366

Summary

Keywords

FRAIL, frailty, kidney transplant, waiting list, candidate

Citation

Pérez-Sáez MJ, Melilli E, Arias M, Franco A, Martínez R, Sancho A, Molina M, Facundo C, Polanco N, López V, Mazuecos A, Cabello S, González García ME, Suárez ML, Auyanet I, Espi J, García Falcón T, Ruiz JC, Galeano C, Artamendi M, Rodríguez-Ferrero ML, Portolés JM, Santana MA, Martín-Moreno PL, Arhda N, Calvo M, Mendiluce A, Macía M, Pérez-Tamajón ML, de Teresa J, Gascó B, Soriano S, Tabernero G, de la Vara L, Ramos AM, Martínez R, Montero de Espinosa E, Zalve JL, Pascual J, Rodríguez-Mañas L, Gutiérrez-Dalmau A and Moreso F (2025) Frailty Prevalence and Characterization Among Kidney Transplant Candidates in Spain: A Multicenter Study. Transpl. Int. 38:14098. doi: 10.3389/ti.2025.14098

Received

21 November 2024

Accepted

30 May 2025

Published

24 June 2025

Volume

38 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Pérez-Sáez, Melilli, Arias, Franco, Martínez, Sancho, Molina, Facundo, Polanco, López, Mazuecos, Cabello, González García, Suárez, Auyanet, Espi, García Falcón, Ruiz, Galeano, Artamendi, Rodríguez-Ferrero, Portolés, Santana, Martín-Moreno, Arhda, Calvo, Mendiluce, Macía, Pérez-Tamajón, de Teresa, Gascó, Soriano, Tabernero, de la Vara, Ramos, Martínez, Montero de Espinosa, Zalve, Pascual, Rodríguez-Mañas, Gutiérrez-Dalmau and Moreso.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: María José Pérez-Sáez, mperezsaez@hmar.cat

‡These authors share senior authorship

ORCID: María José Pérez-Sáez, orcid.org/0000-0002-8601-2699; Edoardo Melilli, orcid.org/0000-0001-6965-3745; Marta Arias, orcid.org/0000-0001-8023-2589; Antonio Franco, orcid.org/0000-0002-1349-1764; Asunción Sancho, orcid.org/0000-0002-4170-9003; María Molina, orcid.org/0000-0003-0033-4214; Carme Facundo, orcid.org/0000-0003-1254-5553; Verónica López, orcid.org/0000-0002-1793-7065; Auxiliadora Mazuecos, orcid.org/0000-0002-5860-2309; Sheila Cabello, orcid.org/0000-0001-9319-6935; María Elena González García, orcid.org/0000-0003-2003-4737; Ingrid Auyanet, orcid.org/0009-0001-4452-4370; Jordi Espi, orcid.org/0000-0003-2443-1035; Juan Carlos Ruiz, orcid.org/0000-0002-7904-8730; Cristina Galeano, orcid.org/0000-0003-2785-8886; José María Portolés, orcid.org/0000-0002-2114-1385; María Auxiliadora Santana, orcid.org/0009-0001-1198-2631; Paloma Martín-Moreno, orcid.org/0000-0001-5335-0555; Marta Calvo, orcid.org/0000-0002-5894-5360; Manuel Macía, orcid.org/0000-0002-0011-7706; María Lourdes Pérez-Tamajón, orcid.org/0000-0001-9812-5706; Javier de Teresa, orcid.org/0000-0002-3416-5490; Sagrario Soriano, orcid.org/0000-0002-0530-3022; Guadalupe Tabernero, orcid.org/0000-0002-1917-0769; Lourdes de la Vara, orcid.org/0009-0005-5835-0147; Ana María Ramos, orcid.org/0000-0001-8137-8483; Julio Pascual, orcid.org/0000-0002-4735-7838; Leocadio Rodríguez-Mañas, orcid.org/0000-0002-6551-1333; Alex Gutiérrez-Dalmau, orcid.org/0000-0002-2253-7779; Francesc Moreso, orcid.org/0000-0002-7267-3963

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.