Abstract

Soil has rarely been represented as the central object in the art of painting. Its occasional presence on canvases appears to be accidental, not depicted for itself but as a subordinate element of the landscape. In pictorial works, it is more frequently shown on its surface and rarely seen in profile or with the details that interest soil scientists. However, exceptionally, certain pictorial works show striking images of the soil, even allowing us to recognize its horizons and other soil features, which can be interpreted with today’s knowledge. In the history of Western art, we observe that this has occurred coinciding with the periods in which naturalistic landscape painting developed. At such times, artists more frequently left their studios to take sketches from nature and, occasionally, to execute complete works outdoors, capturing details of reality not perceived in other artistic periods, including subtle characteristics of the soil. This would first occur in the 17th century, in the landscape art that emerged in the Nordic countries, and particularly in Dutch painting. This would later occur in the 19th century, especially in the landscape painting movements manifested in the so-called English School, the Barbizon School, and the Hague School. This article identifies and justifies, in their historical and cultural context, the paintings and painters who, during these exceptional artistic periods, focused more specifically on the representation of the soil.

Introduction

Soil provides a wide range of ecosystem services, as is now widely recognized. These include the traditionally valued services of providing food and fiber, as well as the performance of a wide variety of environmental functions, which have gained relevance in current public discourse. However, at the same time, they have played and continue to play an important role in other aspects that have been less considered, such as cultural aspects, whether aesthetic, spiritual, or other ethical and knowledge dimensions.

The appreciation of these cultural values of soil is still incipient and insufficiently explored. However, the need to enrich the view of soil with new perspectives is already being pointed out, while opening new frontiers for soil science. Expanding knowledge about soil through different visions would also serve, reciprocally, to attract the attention of a broader audience than the restricted one of soil scientists, and in general would allow for greater communication between soil scientists and society.

In this sense, for some time now, some soil scientists have paved the way for greater interaction with other areas of scientific, humanistic, and artistic culture (Jenny, 1968; Wessolek, 2002; Hartemink, 2009; Toland and Wessolek, 2010; Feller et al., 2010; 2015; Landa and Feller, 2010; Toland and Wolter, 2023; Moscatelli and Marinari, 2024). Furthermore, creative methods have even been explored to develop this interdisciplinary dialogue in a practical way, particularly with art.

The art of painting, by offering a visual and eloquent representation, generally recognizable, allows us to interpret how the soil was once viewed. Therefore, to a certain extent, it can be useful as a documentary source and cultural indicator.

The soil was gradually represented in Western pictorial art, almost in parallel with the birth and evolution of the landscape in painting, whose origins can be traced back to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, until its later full consecration, evolving under different pictorial styles. Consequently, the soil was observable in paintings long before the soil science was established as a scientific discipline, which has developed in just 150 years of history, taking Dokuchaev as its founding reference, commonly considered the father of pedology (Hartemink, 2009; Brevik and Hartemink, 2010; Díaz-Fierros, 2011).

However, in these ancient paintings, soil is never depicted as a central object in itself, but rather as a subordinate element of the landscape. Furthermore, its representation is rarely observed in the detail shown in other natural elements, such as rocks or vegetation, for example. At the same time, from the outset, most paintings show the soil only in its superficial features, and less frequently its profile is observable, making it impossible to view it in three dimensions, as studied by soil scientists.

The soil profile only becomes visible in paintings when it is exposed in slope cuts, along roadsides or on escarpments. Even so, the differentiation of horizons or other soil characteristics would rarely be observable without prior excavation of the profile, which is inconceivable in times long before the scientific observation and knowledge of the soil. However, exceptionally, some paintings show eloquent soil images with textures, colors, or chromatic combinations corresponding to soil features that can identified with today’s knowledge.

In this paper, we examine how the soil has been viewed in the history of pictorial art within Western culture. At the same time, we discuss the social and cultural context in which these paintings are situated. We will focus in particular on the two periods in which we believe soil and landscape have been most faithfully represented pictorially. According to our hypothesis, this occurred in the 17th and 19th centuries, when naturalistic movements were particularly developing in art.

Previous Studies

The representation of soil in the history of Western pictorial art has attracted the recent interest of some authors, who have pointed to selected paintings they considered the most representative examples. A pioneer in addressing this issue was Hans Jenny, best known for having developed a formula for the combined action of the factors of soil formation (Jenny, 1941), who later published a brief history of soil in art, from medieval to contemporary times (Jenny, 1968).

More recent contributions by other authors, in addition to highlighting some early representations of soil in art, also examine its image in parallel with the development of soil science, reflected in textbooks and other publications, as well as the more recent use of soil as an artistic medium. Hartemink (2009), for example, in a historical review, refers to precursor paintings of soil as well as its first representations in scientific literature. He also refers to the appearance in the mid-1950s of colour diagrams of soil profiles, mainly water paintings, such as those published by Kubiena (1954). He points out how they would later be illustrated with photographs, initially in black and white, and from the 1960s/1970s also with colour photos; and finally he describes the use of earth as a medium for artistic performances at the present time.

Similarly, other authors review the historical representation of soil in art and science, and also show interest in certain proposals from contemporary art (Toland and Wessolek, 2010; Feller et al., 2010; 2015). In relation to this last aspect, the interest in creative modalities that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, generally known as Land Art, Eco Art, etc., is noteworthy. In fact, some soil scientists have proposed classifying them as “Soil Art” (Wessolek, 2002; Toland and Wessolek, 2010). Even cinematic representations of soil have been reported (Landa, 2010; Ganga et al., 2023), adding to other varied and original forms of cultural interpretation of soil (Minami, 2009; Landa and Feller, 2010).

Likewise, in our own contributions, we have pointed out two paintings that represent the soil profile in a truly interesting way (Pérez Moreira, 2016). They correspond precisely to the two historical moments mentioned above in which naturalism triumphed in art. These paintings were included in the annual calendar published by the Spanish Society of Soil Science dedicated to soil and art (Sociedad Española de la Ciencia del Suelo, 2016; Mataix-Solera et al., 2017).

The Soil in Precursor Paintings

Some pictorial antecedents show only the surface soil, sometimes showing the furrows in the earth, turned over by the plow during agricultural tasks. Early and well-known examples include, for example, a miniature from the “Calendiers” Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (1413–1416), mostly attributed to Pol de Limbourg,1 as well as the painting The Fall of Icarus (c. 1558–1560) by Pieter Brueghel the Elder.2

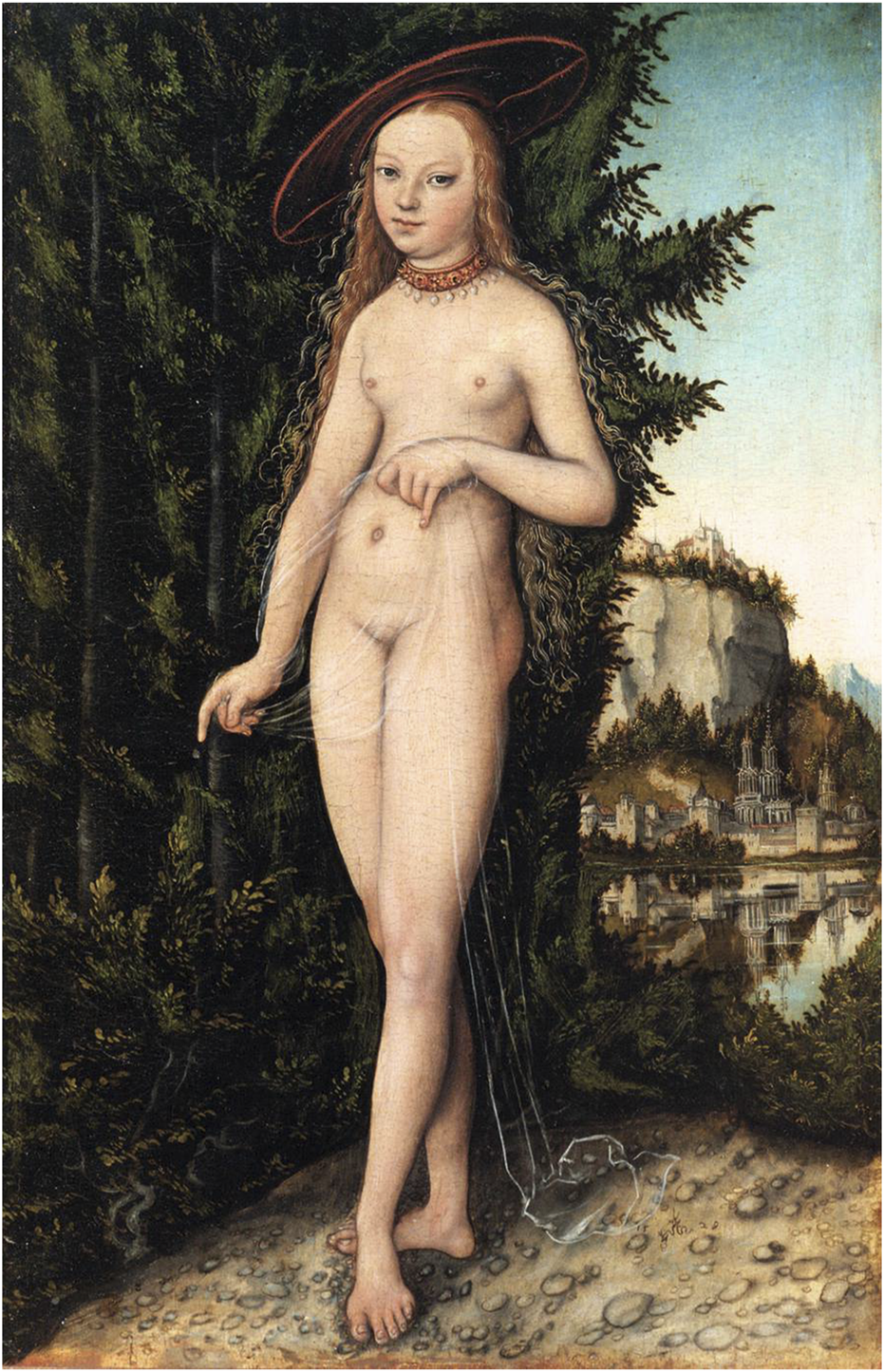

Regarding the representation of the soil in depth, some pioneering paintings suggest the existence of the soil beneath the surface, without actually depicting the soil profile (Pächt, 1997). Prominent examples include the following paintings: Last Judgment (c. 1443–1451) by Rogier van der Weyden;3The Last Judgment (c. 1466–1473) by Hans Memling;4St. John the Baptist in the Wilderness (c. 1489) by Hieronymus Bosch;5Quattro allegorie-perseveranza (c. 1490) by Giovanni Bellini;6The Discovery of Honey by Bacchus (c. 1499) by Piero di Cossimo;7The Tempest (c. 1508) by Giorgione;8Vénus debout dans un paysage (1529) by Lucas Cranach the Elder9 (Figure 1). In some of such representations the soil has an essentially symbolic character, often lending itself to allegories alluding to the Resurrection of the dead, or serving as an excuse to display plant roots, also with a symbolic meaning (Feller et al., 2010; 2015).

FIGURE 1

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Vénus debout dans un paysage (c. 1529), Musée du Louvre. Paris, France. Image from: https://lucascranach.org/en/F_MdLP_1180/.

However, the soil profile is clearly observable in other early paintings. Good examples are the following: Pan y Siringa (c. 1510) by Giovanni Agostino da Lodi (Pseudo Boccaccino)10 (Figure 2), active in Venice in the early 16th century, where a darkened horizon A is shown above the talus. Also in several works by Lodewijk de Vadder, a 17th-century Flemish painter, where a deep talus appears, showing reddish-brown or ochre soil tones, such as in A Hilly Landscape with Travellers and a Wagon on a Path (1640)11 (Figure 3), in Sunken Road with Figures in the Sonian forest (c. 1640s-50s)12 (Figure 4), or in Landscape with Hunters (1640s-50s)13. Likewise, even though no soil features are observed, an eloquent representation of the soil on its surface and in its profile, used in a precursory way as the main element that gives perspective to the painting, can be seen in Country Road by a House (1619–1620), by the German painter Goffredo Wals14 (Figure 5).

FIGURE 2

Giovanni Agostino da Lodi (Pseudo Boccaccino), Pan y Siringa (c.1510), Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, España. Image from: https://www.museothyssen.org/coleccion/artistas/lodi-giovanni-agostino-da/pan-siringa.

FIGURE 3

Lodewijk de Vadder, A hilly landscape with travellers and a wagon on a path (c. 1640), private collection (up for auction on 10/25/2017 in Bonhams, London). Image from: https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/24056/lot/228.

FIGURE 4

Lodewijk de Vadder, Sunken Road with Figures in the Sonian forest (1640/50), Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent, Belgium. Image from: https://www.mskgent.be/en/collection/1938-a.

FIGURE 5

Goffredo Wals, Country Road by a House (1620s). Image from: https://kimbellart.org/collection/ap-199102, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

The Soil in 17th-Century Naturalistic Painting

Social and Artistic Context

There is an accepted consensus that the true birth of landscape in painting occurred at the beginning of the 17th century, in Nordic countries such as Germany and Flanders, and in a definitive way in Holland. Prior to this, there were gradual precedents, initially as a background or simple backdrop for figures. Later, the seemingly central subject became merely a pretext, minimized to magnify the Nature. For example, the landscape was already evident in works by artists such as Konrad Witz (1410–1445) or Joachim Patinir (1480/85–1525). Later, the landscape took on an independent role, devoid of figures, as it is demonstrated in some paintings by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Albrecht Altdorfer (1480–1538), or Pieter Brueghel (1526/30–1569). However, it would not be until this significant moment in the 17th century when certain established criteria were fully met, to consider that the autonomous landscape truly emerged (Berque, 1995; 2009; Roger, 1997). This means that now the landscape is not only the prominent protagonist of the canvas but is an end in itself, not a simple stage subject to a story. Furthermore, it would coincide in time with the diffusion of the word “landscape” itself, which already emerged at the end of the 15th century (Maderuelo, 2006; Roger, 2008; López Silvestre, 2009; Pérez Moreira, 2010).

Historical reasons explain the triumph of the naturalistic landscape painting during the 17th century, which reached its zenith in its middle years, as the culminating artistic moment of what is commonly called the Golden Age of Dutch landscape painting. Political, economic, and religious changes occurred simultaneously. Their origin lay in the rebellion of the Netherlands against the Spanish monarchy, provoking a long war known as the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648). As early as 1579, the Seven United Provinces of the North (Holland) declared themselves an independent republic, separating themselves from the southern provinces (Flanders), which remained under the hegemony of the Spanish crown. The period of war concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Münster, by which Spain recognized the newly independent nation. At the same time, Protestantism replaced Catholicism in the religious dominance in this new nation. From then on, the new nation would experience immediate economic development, driven by a powerful commercial bourgeoisie, becoming one of the leading European powers of the time.

Regarding pictorial art, the traditional institutional and ecclesiastical patronage was lost. This was because in this new secularized and bourgeois society, both the courtly nobility and the Catholic Church ceased to be hegemonic. At the same time, the iconoclasm of the Reformed Church proscribed religious or mythological images, considering them idolatrous. This affected the traditional historical painting, which was restricted to the private sphere of the elite. The triumphant bourgeois class, with less cultural training and less interest in historical representations, appreciated new pictorial genres, including landscapes (Posada Kubissa, 2011).

The art of painting innovatively adapted to social changes (Brown, 1984; Franits, 2004). The new Dutch merchant bourgeoisie emerged as a class interested in owning paintings. A dynamic art market then flourished, becoming popular the small-format genre paintings, especially landscapes. Landscape paintings were collected by all classes of society, even the most modest, constituting almost 40% of artistic production by mid-century (Adams, 1994; Sutton, 1994). This could be partly explained by economic reasons derived from a special relationship with the land, significantly enlarged through the effort to drain wetlands, as in the regions surrounding Haarlem and Amsterdam (Adams, 1994). It could also be due to a certain nostalgia for the traditional rural landscape among a population that was now predominantly urban. But above all, it would be due to a civic pride in representing their free country, its joyful everyday reality, and its landscapes (Hauser, 1998; Adams, 1994; Sutton, 1994; Posada Kubissa, 2009). Landscape painting would therefore be a vehicle for affirming the new national identity.

Artists, in this early period, rarely painted outside their studios (Slive, 1995), but they frequently went into the field to take sketches from nature. These preliminary drawings would be used to create the final work, which was always executed back in their studio or workshop. However, by going outdoors to take sketches in the field, these painters captured details and subtleties previously unperceived, transcending traditional pictorial conventions. At the same time, these excursions allowed them to discover their nature and their country as a landscape.

The final artistic result was a peculiar naturalism in landscape painting, often interpreted as a true vision of its nature. Its apparent objectivity was based on a thorough representation of details. However, they painted scenes that were believable but not real, as they imaginatively reconstructed reality, translated in an exemplary manner. In truth, it was an idealized vision, in which imagination and convention combined with observation (Adams, 1994; Sutton, 1994; Slive, 1995).

This Dutch naturalistic landscape has also sometimes been attributed symbolic meanings, as concepts with moral undertones. However, today’s dominant scholarly opinion questions this overinterpretation (Sutton, 1994; Alpers, 1987). Surely, there would be no other pretension than to mean the simple beauty represented in such landscapes.

The Pictorial Representation of the Soil

The soils of much of the Netherlands have mobile sand deposits as their parent material. These are frequently paleosols interbedded between successive sand layers. In these drifting sands, the youngest soils are little evolved; however, a study of the paleosols shows that most of them developed more or less evident podzolic characteristics (Koster, 2009; Sevink et al., 2023).

Some Dutch artists specialized in painting such dune landscapes, almost from the beginning and during the first half of the 17th century. In all these paintings, the human figure is subordinate, with the dunes as the main subject. One of the first to paint them, in a work dated 1614, was Esaias van de Velde (1587–1630), who was highly influential on later landscape artists (Sutton, 1994). Other artists also inspired by this subject were, mainly, Pieter van Santvoort (1604/05–1635), Jan J. van Goyen (1596–1656), Pieter de Molinj (1595–1661) and Salomon van Ruysdael (1600/03–1670). Likewise, these painters distinguished themselves among the creators of the so-called “tonal phase”, toning the paintings in a unitary, almost monochromatic way, with a reduced palette of colors of warm tones, usually grays and earth tones (Sutton, 1994).

This group of artists laid the foundations for a subsequent “classical phase” of Dutch landscape painting, in which nature and landscape became monumentalized, with solid forms, accentuated contrasts, and more vivid colors (Sutton, 1994; Slive, 1995). These other painters were more versatile in their subjects, but they also represented dunes in their landscapes, either directly or in woodland or other scenes located on dune soils. Notable among these were Jacob I. van Ruisdael (1628/29–1682), Meinder Hobbema (1638–1709), and Philips Wouwerman (1619–1668), while the painter Jan Wijnants (1632/35–1684) stands out for having focused his entire artistic work on painting dunes and dune soils, as will be detailed later.

The soil profile is already hinted at in several of these dune paintings, at least with its A horizon clearly distinguishable. This surface horizon is observable, for example, in works by Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691), such as in A River Scene with Distant Windmills (c. 1640-42),15 as well as in Wooded Landscape with an Artist (c. 1643).16 It is also present in various canvases by Jacob I. Van Ruisdael (1628–1682), an artist renowned for his meticulous depiction of natural elements, particularly his unmistakably recognizable trees. The soil can be seen in several of his works, such as in Road through an Oak Forest (c. 1646-47),17 but more clearly in Dunes (c. 1650-53)18 (Figure 6). The soil profile is much more eloquent in Salomon van Ruysdael’s painting Landscape with Sandy Road (1628)19, where an upper horizon with abundant roots stands out (Figure 7).

FIGURE 6

Jacob I. van Ruisdael, Dunes (c. 1650/53). Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA. Image from: https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/102356.

FIGURE 7

Salomon van Ruysdael, Landscape with Sandy Road (1628), Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California, USA. Image from: https://www.nortonsimon.org/art/detail/F.1970.15.P/.

Jan Wijnants (Haarlem, 1632/35–Amsterdam, 1684) stands out not only for his exclusive specialization in dune paintings but also for his representation of distinct soil horizons. Like many other artists of the time, his thematic specialization was probably due to the demands of a market saturated with painters and paintings, which were quoted at very low prices, forcing them to focus on the topics in which they achieved greater recognition (Sutton, 1994; Slive, 1995).

This artist was inspired by the dunes near his native Haarlem. However, what is surprising is that his paintings with the most expressive soil horizons date from a period when he no longer lived there but in Amsterdam, where he would move permanently in December 1660. In paintings prior to this date, the soil profile is not clearly observed; however, in later works, the soil details are not merely anecdotal, but exceptional for their time and undoubtedly the result of prior observation, even though it later became a particular convention, repeated in varying degrees throughout his paintings.

In almost all of his paintings executed after 1660, the superficial A horizon can be clearly distinguished above the dune substrate, and in several of them podzolic soils can also be distinguished, with a distinctive eluvial horizon (E) and even an underlying illuvial spodic B horizon (Bh, Bs). Among the best examples of this, the following works can be highlighted: A wooded landscape with figures walking by a sandy bank (1659-60),20 perhaps the only one that could be done when he was still living in Haarlem; A Track by a Dune, with Peasants and a Horseman (c. 1655);21Landscape with Hunters (c. 1660-80)22 (Figure 8) and Landschap met twee jagers (1665–1684)23 (Figure 9). However, we consider that the most eloquent example of a soil profile, with features that can now be recognized as podzols, is observed in his painting The Dunes near Haarlem (1667)24 (Figure 10).

FIGURE 8

Jan Wijnants, Landscape with Hunters (c. 1660-80), Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, USA. Image from: https://www.clevelandart.org/art/2011.48.

FIGURE 9

Jan Wijnants, Landschap met twee jagers (1665–1684), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Image from: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/object/Landscape-with-two-Hunters--e3afc5e0ceb3f4f89930d90913809209?tab=data.

FIGURE 10

Jan Wijnants, The Dunes near Haarlem (1667), National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin. Image from: https://www.nationalgalleryimages.ie/search/?searchQuery=Jan+Wijnants%2C+The+Dunes+near+Haarlem, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The Soil in 19th-Century Naturalistic Painting

Social and Artistic Context

Early 19th-century Europe emerged from successive wars and political turmoil in several countries, where an incipient Industrial Revolution was already emerging. England was at the forefront of progress, followed by France and the Netherlands, and then Germany. Industrial prosperity, above all, empowered a new bourgeoisie, wielding a power that until then had been held almost exclusively by monarchs and aristocrats (Pérez-Reverte, 2024).

Pictorial art, consequently, was no longer driven, as it once was, by the desire to express the grandeur of power, as expressed in traditional history paintings. This allowed artists to develop their individuality with fewer constraints (Hauser, 2003). Moreover, painters could not escape the new reality that manifested itself with the advances of progress over the course of the century. Nor will they be immune to the attraction aroused by scientific discoveries and the development of the natural sciences. Even some artists, along with poets, geographers, geologists, adventurers, etc., will participate in the intellectual atmosphere and desire for discovery of scientific excursionism, which will develop mainly at the end of the century. In this context, a certain convergence of scientific and humanistic cultures would occur, motivated by a shared interest in nature and the landscape (Pena, 1998; Casado de Otaola, 2010; Martinez de Pisón, 2017).

The great masters of the Golden Age of Dutch landscape painting exerted a notable influence on this 19th-century landscape painting, serving as inspiration for the resurgence of a new naturalism. Thus, for example, Thomas Gainsborough and John Constable, pioneers of this emerging trend, looked back and studied with devoted admiration the paintings of Ruisdael, Hobbema, and Wijnants, as did other painters involved in this artistic movement. It could therefore be argued that the most revolutionary and lasting contribution of the Dutch landscape painting precedent was its naturalism (Sutton, 1994). Thus, naturalism and the practice of outdoor painting are once again appreciated. Now artists will approach painting from nature in a more consistent manner, with plein air painting becoming a success.

In the preceding 18th century, the socio-historical circumstances and the prevailing aesthetic criteria were not conducive to an equivalent development of pictorial naturalism and plein-air painting. Both were disparaged even in their country of origin, declining there shortly after reaching their zenith, especially due to the subsequent artistic and normative expansion of French academicism (Pena, 2000; López-Manzanares, 2013).

Open-air painting was unusual, with a few exceptions. This was partly because it was not valued as a priority in the pictorial tradition. Likewise, landscape painting was still considered a minor genre in the pictorial hierarchy, secondary to history painting, which enjoyed the highest academic recognition. But it was also the case, especially with oil painting, that its execution in the field was technically complicated until certain technical innovations facilitated the task. Specifically, the invention of paint tubes and portable or field easels, in the mid-century, simplified fieldwork and led to the further development of this plein air activity (Graham-Dixon et al., 2020).

For some time now, highly influential treatises had dictated standards regarding landscape painting and open-air painting. Among the most famous were those written by Karol van Mander (published in 1604), Roger de Piles (published in 1708), and Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (published in 1800), which remained reference texts for a long time. In all of them, the practice of painting from life was advocated, but solely for the purpose of acquiring a repertoire of notes with which to later compose the complete work, which invariably had to be developed in the studio (López-Manzanares, 2013; Pomarède, 2013). In other words, sketches that were simply copies from life were not yet considered true art, but rather what was subsequently recomposed and reinvented with them. What was valued as art was not imitation but creation, and not the landscape elements themselves, but their composition as an integral part of historical painting.

Another preliminary step on the path to the full triumph of pictorial naturalism was to overcome the sublime fantasies characteristic of Romanticism. At this earlier stage, nature was not yet an end but a means of expressing feelings. However, in their romantic exaltation, some artists elevated landscape painting to the level of recognition of historical painting. With them, the pictorial category of the “picturesque” would also be confirmed. In their struggle against the rules imposed on art, they anticipated “l’art pour l’art” (art for its own end), an art more free of prejudice, with its consequent freedoms for artistic development (Hauser, 2003).

After Romanticism’s flight from reality, a return to it arose with Realism. The aim was no longer to create a breathtaking or picturesque setting, but rather to faithfully reproduce nature as it is, as a natural entity, of interest in itself. The theoretical discourse would also adjust to this shift in approach. For example, John Ruskin, in his monumental work Modern Painters (1843–1860), in his advice to young painters, specified that nature should be copied truthfully “in the best way of penetrating its meaning; without rejecting anything, without choosing anything and without despising anything” (Ruskin, 1848).

In contemporary naturalistic/realistic painting, work from life would no longer be secondary and subordinate to its completion in the studio, as had been the case until then. The balance nature-studio, as well as the gradation between faithful reproduction or the reproduction of one’s own feelings, would depend on the will of each artist (López-Manzanares, 2013). Furthermore, in contrast to the academic postulates of the “universal” and the “ideal,” in Realism the “local” and the “real” prevail (Pena, 2000). This painting demonstrates sincerity and meticulous attention to detail. In it, natural elements are no longer simply decorative elements of the composition, but are reproduced as singular entities and according to their own reality.

This new naturalistic landscape painting would develop in Europe mainly in three areas, which are now retrospectively referred to as the English School, the Barbizon School, and the Hague School.

The English School of landscape painters of the early 19th century was partly a Romantic expression, partly a transcendence of Romanticism, and the initiator of Naturalism (Hauser, 2003). Its landscape painters were pioneers in the practice of open-air painting. However, the opportunity for definitive academic recognition of the landscape genre and plein air painting arose in France with the creation in 1817 of the “Grand Prix de Rome de paysage historique”, an award that included a coveted two-year pension in Rome (Pomarède, 2013). One of the most feared exercises was the “tree test,” which required many of the candidates to practice painting studies in forests near the French capital, the most notable being the Forest of Fontainebleau.

The Barbizon School is the name given to the group of painters who came to this French village, about 50 km southeast of Paris, to find inspiration in the nearby Fontainebleau forest. This place would attract several generations of landscape artists to paint outdoors, primarily between 1820 and 1860 (Schama, 1999; Hauser, 2003; Oropesa and Caille, 2007; López-Manzanares, 2013; Schulman, 2013). However, they did not constitute a uniform movement or a shared ideal, having only in common a rejection of imposed academic rules and an enthusiasm for painting from nature (Hauser, 2003; Schulman, 2013).

The Hague School refers in turn to those painters who in Holland followed similar paths to those taken by the Barbizon artists, whose equivalent here would be the village of Oosterbeek, in the eastern part of the country. Many of the painters in this group were previously attracted to the Fontainebleau forest, and later developed their Dutch activity mainly between 1860 and 1885 (Suijver, 2009).

The Pictorial Representation of the Soil

In the English School of landscape painting, which had already emerged in the previous century, the view of the soil was anticipated in some paintings. The soil profile appears -although its horizons are not clearly defined- in several works by Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788), such as A View in Suffolk (1746-47)25 (Figure 11). However, it was the work of John Constable (1776–1837) that marked a substantial change from earlier landscape artists. He is considered one of the first artists to paint deliberately outdoors, having begun doing so in 1810 and continuing for most of his life. This painter was a pioneer in a period of transition between Romanticism and Realism, incorporating truth and emotion, although his painting was not an exact realism. The soil profile is clearly shown in several of his paintings, such as Dedham Vale (1802)26 (Figure 12) or Dell at Helmingham Park (c. 1825-26),27 in which the surface horizon and other soil features are distinguished. Another British painter of this period was J. M. William Turner (1775–1851), also ahead of his time, who himself would move away from figurative and realistic painting, dissolving forms and colors, and advancing the art of later times; the upper horizon of the soil is suggested in his work The Bay of Baiae with Apollo and the Sibyl (1823).28

FIGURE 11

Thomas Gainsborough, A View in Suffolk (1746-47), National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin. Image from: https://www.nationalgalleryimages.ie/search/?searchQuery=Thomas+Gainsborough%2C+A+View+in+Suffolk, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

FIGURE 12

John Constable, Dedham Vale (1802), Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK. Image from: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O69881/dedham-vale-oil-painting-constable-john-ra/.

In the Barbizon School, the painters who anticipated naturalistic landscape painting were Georges Michel (1763–1843) and Làzare Bruandet (1755–1804), who made their first field trips together to paint from life, doing so in places close to Paris. They also represented a turning point in landscape art, moving away from the idealist tradition of classicism, capturing in their paintings both reality and the artist’s feelings. The soil is intuited in works by Georges Michel such as Landschap met zandweg (1820),29 but the soil profile is more clearly seen in works by Làzare Bruandet -one of the first to visit the Fontainebleau Forest-, as in Vue prise dans le forêt de Fontainebleau (1785),30 and in Paysage avec chasseurs (c. 1780-90),31 where the upper horizon can be clearly distinguished.

The soil profile was eloquently represented in paintings by Jacques-Raymond Brascassat (1804–1867) and Jean Baptiste Camille Corot (1796–1875), who were also among the first landscape artists to regularly visit the Fontainebleau Forest, back in the 1920s and early 1930s, and were the true precursors of the Barbizon School.

In Brascassat, the soil profile is evident in his painting Rochers en forêt (1828)32 (Figure 13), which for a long time was considered to have been executed in the Fontainebleau forest, although this was not true. In fact, having been awarded second prize at the Grand Prix de Rome in 1825, he remained in Italy between 1826 and 1830, coinciding with the period in which he produced this painting, along with many others in which he depicted nature, composing paintings based on sketches taken from life. Another good example is seen in Clairière en forêt (1828).33 Upon his return to Paris, he gained a reputation for animal paintings in which the soil profile is also visible in the foreground, such as Un combat de taureau (1855).34

FIGURE 13

Jacques-Raymond Brascassat, Rochers en forêt (1828), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Reims, France. Image from: https://musees-reims.fr/oeuvre/rochers-en-foret, by Christian Devleeschauwer, licensed under CC BY 2.0 FR.

In Corot, the truly realist intention is observed in his painting Carrière de Chaise-Marie à Fontainebleau (1831)35 (Figure 14). It is a representation, not at all picturesque, of a fragment of nature that is interrupted by the frame of the painting, appearing to have been drawn directly from nature. This painting attests to the importance of the observation and truthful reproduction of nature, including the reproduction of the soil.

FIGURE 14

Jean Baptiste Camille Corot, Carrière de Chaise-Marie à Fontainebleau (1831), Musée des Beaux-Arts Gand, Belgique. Image from: https://www.mskgent.be/fr/collection/1914-di.

In the Hague School, we must highlight Willem Roelofs (1822–1897), one of its precursors and a leader of the movement in its early days. He was previously involved with the Barbizon School of Realists, visiting the Forest of Fontainebleau on three occasions. In his painting Landschap bij naderend onweer (1850)36 (Figure 15), the soil appears to be part of an old riverbed, seen on its surface rather than in profile. Likewise, his painting Forêt de Fontainebleau (c. 1852-55)37 is a good example of the realistic reproduction of details in this naturalistic art, with its meticulous representation of trees, rocks, and even soil.

FIGURE 15

Willem Roelofs, Landschap bij naderend onweer (1850), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Image from: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/object/Landschap-bij-naderend-onweer--525e62041874927f3ac3c5ed30ef0523.

As naturalism developed in the aforementioned English, Barbizon, and Hague schools, paintings in this style were also produced in other European countries. For example, in Spain, where the Belgian-born painter Carlos de Haes (1826–1898), would create a naturalist school of landscape at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid, popularizing open-air painting and the faithful reproduction of natural reality (Pena, 1998; 2014; Gutiérrez Marquez, 2004; Casado de Otaola, 2010). Another example, also significant, is that of the Catalan landscape painter Joaquim Vayreda (1843–1894), who contributed to the founding of the renowned Olot School. Both artists, familiar with the pictorial work of Barbizon, suggest the vision of the soil in some of his paintings.

Finally, many of the painters who initially participated in this naturalistic art would later move toward other, less narrative and more informalist artistic styles. Among them were some of the best-known artists who practiced plein-air painting in the Fontainebleau forest. They initially evolved toward Impressionism, still a radically plein-air art, and later advanced toward other formulas, labeled as Symbolism, Fauvism, Expressionism, etc., in successive distortions on the path to abstraction and modernity (Thomson, 2014). To a certain extent, toward the end of the century, the prevailing naturalism was rejected in favor of new creative codes, no longer figurative but rather conceptual. Painters now sought to distinguish themselves with their own style that distanced themselves from the merely descriptive, replacing external reality with one born from the artist’s spirit. Consequently, under these new aesthetic parameters, the faithful reproduction of nature loses interest, while the soil profile would no longer be represented in a recognizable and realistic way.

Conclusion

Soil is very rarely represented explicitly and for itself in the history of painting. However, exceptionally, some early paintings already show soil horizons and soil features in some detail, which we can even identify with today’s knowledge.

This work shows that the most eloquent pictorial representations of the soil emerge, in Western art, at the same time as the development of naturalistic currents in landscape painting, as occurred primarily during the 17th and 19th centuries, due to exceptional circumstances that favored the open-air pictorial exercise. This allowed painters to perceive subtleties of Nature and landscape not observed with equal precision in other artistic periods. However, from the end of the 17th century and throughout the 18th century, the socio-historical context and the prevailing aesthetic criteria were not equally conducive to an equivalent development of pictorial naturalism and plein-air painting.

The pictorial representation of soil is especially notable in those two aforementioned periods. Particularly noteworthy are works from 17th-century Dutch painting, as well as from the English, Barbizon, and Hague schools, developed in the 19th century. This pictorial exceptionality is justified by the social and cultural context that have been discussed, pointing out the historical conditions and aesthetic codes under which these artistic works were created.

Finally, as a complementary reflection to this study, we consider that the art of painting offers interesting new aspects regarding soil. On the one hand, its pictorial image can serve as a documentary source and cultural indicator, testifying to how soil was viewed in earlier historical periods, prior to the birth of soil science. On the other hand, pictorial art can help provide an attractive image of soil for both the public and soil scientists themselves. Artistic representations of the soil, in their various forms, both figurative art and other innovative forms experimented with in contemporary art, contribute to its dissemination and greater awareness by society. At the same time, it can favor a beneficial interdisciplinary approach between scientific and humanistic fields, even collaborating with artists and educators, thus opening up new opportunities for soil science.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

RP conceptualized the work, carried out the bibliographic review and contributed to the writing of the text. MB participated in the selection of the more representative paintings and contributed to the writing of the text. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

1.^Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (1413–1416), largely attributed to Pol de Limbourg, Musée Condé, Chantilly, France.

2.^The Fall of Icarus (c. 1558–1560), Pieter Brueghel the Elder. Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Bruxelles, Belgique.

3.^Last Judgment (c. 1443–1451), Rogier van der Weyden, Musée Hôtel-Dieu, Beanne, France.

4.^The Last Judgment (c. 1466–1473), Hans Memling, National Museum of Gdansk, Poland.

5.^St John Baptist in the Wildeners (c. 1489), Hieronymus Bosch, Museo Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid.

6.^Quattro Allegorie-perseveranza (c. 1490), Giovanni Bellini, Gallerie Accademia, Venezia, Italia.

7.^The Discovery of Honey by Bacchus (c. 1499), Piero di Cossimo, Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, USA.

8.^The Tempest (c. 1508), Giorgione, Accademia di Belle Arti, Venezia, Italia.

9.^Vénus debout dans un paysage (c. 1529), Lucas Cranach the Elder, Musée du Louvre. Paris, France.

10.^Pan y Siringa (c. 1510), Giovanni Agostino da Lodi (Pseudo Boccaccino), Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, España.

11.^A hilly landscape with travellers and a wagon on a path (c. 1640), Lodewijk de Vadder, private collection (up for auction on 10/25/2017 in Bonhams, London).

12.^Sunken Road with Figures in the Sonian forest (1640-50), Lodewijk de Vadder, Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent, Belgium.

13.^Paisaje con cazadores (1640s-50s). Lodewijk de Vadder, Museo del Prado, Madrid, España.

14.^Country Road by a House (1620s), Goffredo Wals, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, USA.

15.^A River Scene with Distance Windmills (c. 1640-42), Aelbert Cuyp, National Gallery, London, UK.

16.^Wooded Landscape with an Artist (c. 1643), Aelbert Cuyp, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, USA.

17.^Road through an Oak Forest (1646-47), Jacob I. Van Ruisdael, Staten Museum for Kuns, Copenhagen, Denmark.

18.^Dunes (c. 1650/53). Jacob I. Van Ruisdael, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA.

19.^Landscape with Sandy Road (1628), Salomon van Ruysdael, Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California, USA.

20.^A wooded landscape with figures walking by a Sandy Bank (1659-60), Jan Wijnants, Manchester Art Gallery, UK.

21.^A Track by a Dune, with Peasants and a Horseman (c. 1665), Jan Wijnants, National Gallery, London, UK.

22.^Landscape with Hunters (c. 1660-80), Jan Wijnants, Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, USA.

23.^Landschap met twee jagers (c. 1665–1684), Jan Wijnants, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

24.^The Dunes near Haarlem (1667), Jan Wijnants, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

25.^A View in Suffolk (1746-47), Thomas Gainsborough, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

26.^Dedham Vale (1802), John Constable, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

27.^The Dell at Helmingham Park (1825-26), John Constable, Philadelphia Museum of Arts, USA.

28.^The Bay of Baiae with Apollo and the Sibyl (1823), J. M. William Turner, Tate Britain, London, UK.

29.^Landschap met zandweg (1820), Georges Michel, Museum Gouda, Netherlands.

30.^Vue prise dans le forêt de Fontainebleau (1785), Làzare Bruandet, Louvre Collections, on loan at Palaix du Luxenbourg-Sénat, Paris, France.

31.^Paysage avec chasseurs (c. 1780s-90s), Làzare Bruandet, Musée National Magnin, Dijon, France.

32.^Rochers en forêt (1828), Jacques-Raymond Brascassat, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Reims, France.

33.^Clairière en forêt (1828), Jacques-Raymond Brascassat, Musée Paul-Dupuy, Toulouse, France.

34.^Un combat de taureau (1855). Jacques Raymond Brascassat, Musum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, USA.

35.^Carrière de Chaise-Marie à Fontainebleau (1831), Jean Baptiste Camille Corot, Musée des Beaux-Arts Gand, Belgique.

36.^Landschap bij naderend onweer (1850), Willem Roelofs, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

37.^Forêt de Fontainebleau (c. 1852-55), Willem Roelofs, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

References

1

AdamsA. J. (1994). “Competing Communities in the «Great Bog of Europe». Identity and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Landscape Painting,” in Landscape and Power. Editor MitchellW. J. T. (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press), 35–76.

2

AlpersS. (1987). “Introducción” and “Apéndice”, in El arte de describir: el arte holandés del siglo XVII. Madrid: Hermann Blume, 17-31 and 311–316.

3

BerqueA. (1995). Les Raisons du paysage: De la Chine antique aux environnements de synthése (París: Hazan), 192.

4

BerqueA. (2009). in El Pensamiento Paisajero. Editor MaderueloJ. (Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva), 144.

5

BrevikE. C.HarteminkA. E. (2010). Early Soil Knowledge and the Birth and Development of Soil Science. Catena83 (1), 23–33. 10.1016/j.catena.2010.06.011

6

BrownC. (1984). Scenes of Everyday Life. Dutch Genre Painting of the Seventeenth Century. London: Faber and Faber, 240.

7

Casado de OtaolaS. (2010). Naturaleza patria. Ciencia y sentimiento de la naturaleza en la España del regeneracionismo. Madrid: Marcial Pons Ediciones de Historia, 379.

8

Díaz-FierrosF. (2011). La ciencia del suelo. Historia, concepto y método. Santiago de Compostela: Univ. Santiago de Compostela, 191.

9

FellerC.Chapuis-LardyL.UgoliniF. (2010). “The Representation of Soil in the Western Art: From Genesis to Pedogenesis,” in Soil and Culture. Editors LandaE. R.FellerC. (Dordrecht: Springer), 3–22.

10

FellerC.LandaE. R.TolandA.WessolekG. (2015). Case Studies of Soil in Art. Soil1 (2), 543–559. 10.5194/soil-1-543-2015

11

FranitsW. (2004). Dutch Seventeenth-Century Genre Painting. Its Stylistic and Thematic Evolution. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 328.

12

GangaA.RibeiroL.PaganiniE. A.DilipkumarA.Abreu-JuniorC. H.NogueiraT. A. R.et al (2023). Filming a Hidden Resource: The Soil in Seventh Art Narrative. Geoderma440, 1–12. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116710

13

Graham-DixonA.BraineA.BrayG.ChilvesI.GwynneP.ZaczekL.et al (2020). Historia de la pintura. Cómo Se Hizo Arte (Madrid: Akal), 360.

14

Gutiérrez MarquezA. (2004). Carlos de Haes en el Museo del Prado. Catálogo razonado. Exposición 2004-2005. (A Coruña: Museo de Belas Artes da Coruña), 422.

15

HarteminkA. E. (2009). The Depiction of Soil Profiles since the Late 1700s. Catena79 (2), 113–127. 10.1016/j.catena.2009.06.002

16

HauserA. (1998). Historia social de la literatura y el arte. I: Desde la Prehistoria hasta el Barroco. Madrid: Debate, 567.

17

HauserA. (2003). Historia social de la literatura y el arte. II: Desde el Rococó hasta la época del cine. Madrid: Debate, 539.

18

JennyH. (1941). Factors of Soil Formation. A System of Quantitative Pedology. New York: McGraw-Hill, 281.

19

JennyH. (1968). “The Image of Soil in Landscape Art, Old and New,” in Organic Matter and Soil Fertility (Città del Vaticano: Pontificiae Academia Scientarium. Scripta Varia), 979–1011.

20

KosterE. A. (2009). The “European Aeolian Sand Belt”. Geoconservation of Drift Sand Landscapes. Geoheritage1 (1), 93–110. 10.1007/s12371-009-0007-8

21

KubienaW. L. (1954). Atlas de perfiles de suelos (Madrid: Inst. de Edafología y Fisiología Vegetal, CSIC), 28.

22

LandaE. R. (2010). “In a Supporting Role: Soil and the Cinema,” in Soil and Culture. Editors LandaE. R.FellerC. (Dordrecht: Springer), 83–105.

23

LandaE. R.FellerC. (2010). Soil and Culture (Dordrecht: Springer), 488.

24

López-ManzanaresJ. A. (2013). “Al Aire Libre,” in Impresionismo y aire libre, de Corot a Van Gogh (Madrid: Fundación Colecc. Thyssen-Bornemisza), 13–33.

25

López-SilvestreF. (2009). “Cara a unha teoría integral da paisaxe,” in Olladas críticas sobre a paisaxe. Editors Díaz-FierrosF.López-SilvestreF. (Santiago de Compostela: Consello da Cultura Galega), 93–104.

26

MaderueloJ. (2006). El paisaje, génesis de un concepto (Madrid: Abada), 344.

27

Martinez de PisónE. (2017). La Montaña Y El Arte. Miradas desde la pintura, la música y la literatura (Madrid: Fórola Ediciones), 614.

28

Mataix-SoleraJ.PochR. M.Díaz-FierrosF.Pérez-MoreiraR.AsinsS.PortaJ.et al (2017). Soil and Art: The Spanish Society of Soil Science Calendar for 2016. Geophys. Res. Abstr.19. Available online at: https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU2017/EGU2017-203.pdf (Accessed July 28, 2025).

29

MinamiK. (2009). Soil and Humanity: Culture, Civilization, Livelihood and Health. Soil Sci. Nutr.55, 603–615. 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2009.00401.x

30

MoscatelliM. C.MarinariS. (2024). Digging in the Dirt: Searching for Effective Tools and Languages to Promote Soil Awareness. Soil Secur.16, 100167. 10.1016/j.soisec.2024.100167

31

OropesaM.CailleM. T. (2007). La Escuela de Barbizón. Catálogo Exposición (Vigo: Centro Cultural Caixanova), 95.

32

PächtO. (1997). Early Netherlandish Painting. From Rogier van der Weyden to Gerard David. Editor RosenauerM. (London: Harvey Miller Publishers), 264.

33

PenaC. (1998). Pintura de paisaje e ideología. La generación del 98 (Madrid: Taurus), 170.

34

PenaC. (2000). “Aspectos da tradición do pintoresco na Colección Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza,” in Texto do Catálogo da Exposición: De Van Goyen a Constable. Aspectos da tradición do pintoresco na Colección Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza (A Coruña: Museo de Belas Artes da Coruña), 221.

35

PenaC. (2014). “La invención del paisaje español,” in Del realismo al impresionismo (Madrid: Círculo de Lectores: Galaxia Gutenberg), 143–165.

36

Pérez MoreiraR. (2010). “A descuberta cultural da paisaxe,” in Cultura e Paisaxe. Editors Pérez MoreiraR.López GonzálezF. J. (Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela), 19–51.

37

Pérez MoreiraR. (2016). “Wijnants, Dunas cerca de Haarlem (1667); Raymond Brascassat, Peñascos en el bosque (1828),” in Suelos Y Arte. Calendario SECS (April, Wijnants; Back Cover, Brascassat) (Madrid: Sociedad Española de la Ciencia del Suelo).

38

Pérez-ReverteA. (2024). “Una Historia de Europa (LXXXVI),” in XL-semanal, 11-VIII-2024.

39

PomarèdeV. (2013). “Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes y los ornamentos de la naturaleza,” in Impresionismo y aire libre, de Corot a Van Gogh (Madrid: Fundación Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza), 35–47.

40

Posada KubissaT. (2009). Pintura holandesa en el Museo Nacional del Prado. Catálogo de la Colección (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado), 336.

41

Posada KubissaT. (2011). “Rubens, Brueghel, Lorena. El paisaje nórdico en el Prado,” in Catálogo de la Colección (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado), 181.

42

RogerA. (1997). Court traitè du paysage (París: Gallimard). Spanish translation, 2007: Breve tratado del paisaje. (Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva), 236.

43

RogerA. (2008). “Vida y muerte de los paisajes. Valores estéticos, valores ecológicos,” in El paisaje en la cultura contemporánea. Editor NoguéJ. (Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva), 67–85.

44

RuskinJ. (1848). Modern Painters. 4th Edn. (London: Smith, Elder and Co.).

45

SchamaS. (1999). Le Paysage et la Mémoire. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 720.

46

SchulmanM. (2013). “La pintura al aire libre en la Escuela de Barbizón,” in Impresionismo y aire libre, de Corot a Van Gogh (Madrid: Fundación Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza), 49–59.

47

SevinkJ.WallingaJ.ReimanT.Van GeelB.BrinkkemperO.JansenB.et al (2023). A Multi-Staged Driff Sand Geo-Archive from the Netherlands: New Evidence for the Impact of Prehistoric Land Use on the Geomorphic Stability, Soils, and Vegetation of Aeolian Sand Landscapes. Catena224, 1–17. 10.1016/j.catena.2023.106969

48

SliveS. (1995). Dutch Painting, 1600-1800. New Haven: Yale University Press, 365.

49

Sociedad Española de la Ciencia del Suelo (SECS) (2016). Suelos y Arte. Calendario SECS (Madrid, Sociedad Española de la Ciencia del Suelo).

50

SuijverR. (2009). “Reflexos da paisaxe holandesa. A pintura da Escola da Haia”, in La Escuela de la Haya. Obras maestras del Rijksmuseum. (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, and Vigo: Fundación Caixanova), 17–37.

51

SuttonP. C. (1994). “Introducción,” in El Siglo de Oro del paisaje holandés. Catálogo de Exposición (Authors P. C. Sutton with the collaboration of J. Loughman) (Madrid: Fundación Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza), 15–57.

52

ThomsonR. (2014). “El caso del «postimpresionismo»: La búsqueda de estilo y el fracaso de una etiqueta estilística,” in Del realismo al impresionismo (Madrid: Círculo de Lectores: Galaxia Gutenberg), 267–287.

53

TolandA. R.WessolekG. (2010). “Merging Horizons – Soil Science and Soil Art,” in Soil and Culture. Editors LandaE. R.FellerC. (Dordrecht: Springer), 45–66.

54

TolandA. R.WolterD. (2023). “Soil Art: Sensory and Symbolic Engagement with Soils,” in Enciclopedia of Soils in the Environment. Editors GoosM. J.OliverM. (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 509–520.

55

WessolekG. (2002). Art and Soil: Newsletter 10 (Rome: The Committee on the History, Philosophy, and Sociology of Soil Science International Union of Soil Science, and Madison: Council on the History, Philosophy, and Sociology of theSoil Science Society of America), 14–15.

Summary

Keywords

soil art, soil culture, painting, landscape, naturalistic landscape painting

Citation

Pérez Moreira R and Barral Silva MT (2025) Soil in Art. Its Representation in Naturalistic Painting of the 17th and 19th Centuries. Span. J. Soil Sci. 15:14834. doi: 10.3389/sjss.2025.14834

Received

29 April 2025

Accepted

14 July 2025

Published

20 October 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Edited by

Raul Zornoza, Polytechnic University of Cartagena, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Pérez Moreira and Barral Silva.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rogelio Pérez Moreira, roxelio.perez.moreira@usc.es

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.