Abstract

The policy landscape explores the policy formulation processes, the policies, and the stakeholders involved in improving governance, implementation of policies, and government commitment in a democratic country. It emphasizes the human development approach that is within the Pastoralism Framework of the African Union (AU), recognizing the link between economic growth and human development through deliberate policies at various levels. The integrated strategies in Kenya’s pastoral policy landscape aim to evaluate progress against the objectives of national development projects and how those objectives are integrated into County-Integrated Development Plans (CIDPs) and outcomes based on Metland’s Ambiguity-Conflict Model. This landscape seeks to frame and advance the changing dynamic of how the current policies and strategies align with the realities of the pastoral sector with an emphasis on livestock production and marketing but recognizing pastoralists are involved in other economic activities such as opportunistic irrigation, fishing, beekeeping, quarry mining, firewood, liquor production, and casual labor. Doing so is to support the alleviation of persistent multidimensional poverty in those regions and improve communication (at the intra-and inter-governmental levels), coordination, and flow of county-level heterogeneous information in support of a centralized policymaking process. It also identifies ways to prioritize pastoral livestock marketing, integrate pastoral issues in decision-making, empower women, and adopt climate adaptation for holistic pastoral transformation.

Introduction

As a livelihood system, pastoralism is deeply rooted in expansive livestock production, relying on the strategic use of sparse natural resources such as water and pastures (Nyariki and Amwata, 2019). Globally, pastoralism spans 25%–45% of the land surface, with Asia and Africa accounting for the most significant shares and cumulatively supporting over five million households (Ameso et al., 2018; Manzano et al., 2021). In Kenya, pastoralism contributes approximately 10% of the national and 50% of the agricultural gross domestic production (GDP) (PACJA and KLMC, 2022), underscoring its economic significance. Despite its resilience in arid and semi-arid lands (ASALs), pastoralism has historically been marginalized in policy frameworks shaped by colonial and post-independence narratives that dismissed it as economically unviable and environmentally destructive (Catley et al., 2013). Despite the increased intensity of stressors such as floods and droughts, pastoral system innovativeness has demonstrated the adaptability to thrive in agro-ecological zones that hinder expansion. Consequently, pastoral production has been credited to be the most suited use of rangelands.

Historical power structures, political interests, and competing knowledge systems have influenced the formulation of pastoral policies in Kenya. Colonial administrations imposed restrictive grazing schemes that disrupted traditional mobility. This trend persisted post-independence through policies like Sessional Paper No. 10 of 1965, prioritizing high-potential agricultural zones over arid and semi-arid lands (ASALs) (Scoones, 2021). These policies were not neutral technical decisions but were shaped by entrenched power relations that favored sedentary agriculture and state control over pastoralist autonomy.

Contemporary policy processes continue to reflect these dynamics. While Kenya’s Constitution and Vision 2030 acknowledge pastoralism, their implementation often prioritizes commercialization and infrastructure over indigenous resource management systems (GoK, 2010b; Gok, 2010a). The National Policy for the Sustainable Development of arid and semi-arid lands and Community Land Act represent attempts to integrate pastoralist concerns, yet their effectiveness is hampered by weak enforcement, bureaucratic resistance, and competing land-use interests (GoK, 2012d; GoK, 2016a). Power asymmetries in policymaking mean that pastoralist voices are often sidelined in favor of elite economic agendas, such as large-scale land acquisitions for conservation or commercial agriculture (African Union, 2013).

Kenya’s pastoral policy landscape has seen notable advancements, particularly in aligning with regional frameworks including the African Union (AU) Policy Framework on Pastoralism and Intergovernmental Authority for Development (IGAD) Protocol on Transhumance and Agricultural Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy (African Union, 2010; IGAD, 2020b; GoK, 2019a). The AU framework advocates for mobility rights, climate resilience, and socio-economic inclusion, challenging the historical marginalization of pastoralists. Kenya’s domestication of the IGAD Protocol marks a significant shift, recognizing cross-border livestock mobility as a legitimate livelihood strategy (IGAD, 2020a).

However, critical gaps remain. While Kenya has adopted progressive policies on paper, implementation is often inconsistent due to fragmented governance, limited county-level capacity, and competing political interests. For instance, the National Livestock Policy promotes pastoralist market access (GoK, 2020b). Nevertheless, high taxation and restrictive trade policies hinder informal cross-border trade, accounting for 71% of live animal exports along the Ethiopia-Kenya border (Berhanu, 2016). Similarly, while the Rangelands Management and Pastoralism Strategy seeks to enhance productivity, its success depends on decentralized decision-making and meaningful pastoralist participation, elements often undermined by top-down policymaking (GoK, 2021b).

While progressive in principle, pastoral policies in Kenya exhibit significant implementation gaps that disproportionately affect women, particularly concerning land rights, economic empowerment, and access to resources. The Community Land Act and National Land Use Policy theoretically safeguard women’s rights to inherit and manage land, yet patriarchal customary practices in pastoralist communities, like Turkana, often exclude women from land ownership, relegating them to precarious livelihoods like charcoal burning (Akall, 2021; GoK, 2016a; Gok, 2017b). The ASAL Policy and National Gender Policy, advocate for women’s financial inclusion, but county-level execution remains weak; for instance, Turkana and Garissa lack gender-responsive revenue policies, and women pastoralists face underrepresentation in local governance (OXFAM, 2022; GoK 2012d; GoK 2019b). Economic empowerment initiatives, such as the Livestock Insurance Program and IGAD Protocol on Transhumance, fail to address gendered barriers women’s limited access to markets, credit, and extension services perpetuates dependency on informal trade (ILRI, 2022). Climate adaptation strategies under the Rangeland Management Strategy neglect women’s unique vulnerabilities, as water scarcity and drought amplify their labor burdens without commensurate support (Marsabit County Government, 2018; GoK, 2021b). Despite constitutional guarantees, the disconnect between national policies and localized patriarchal norms underscores the need for enforced gender audits, grassroots women’s participation in CIDPs, and targeted funding to bridge equity gaps in pastoralist development.

Devolution under the Constitution was intended to empower counties in tailoring policies to local pastoralist needs. However, county governments face challenges in balancing national directives with community priorities. Some counties have integrated pastoralist concerns into County Integrated Development Plans (CIDPs), but others remain constrained by limited funding, weak institutional capacity, and elite capture (GOK, 2017a). The Intergovernmental Relations Act was designed to harmonize national and county policies, but tensions persist, particularly in land and resource governance (GoK, 2012b).

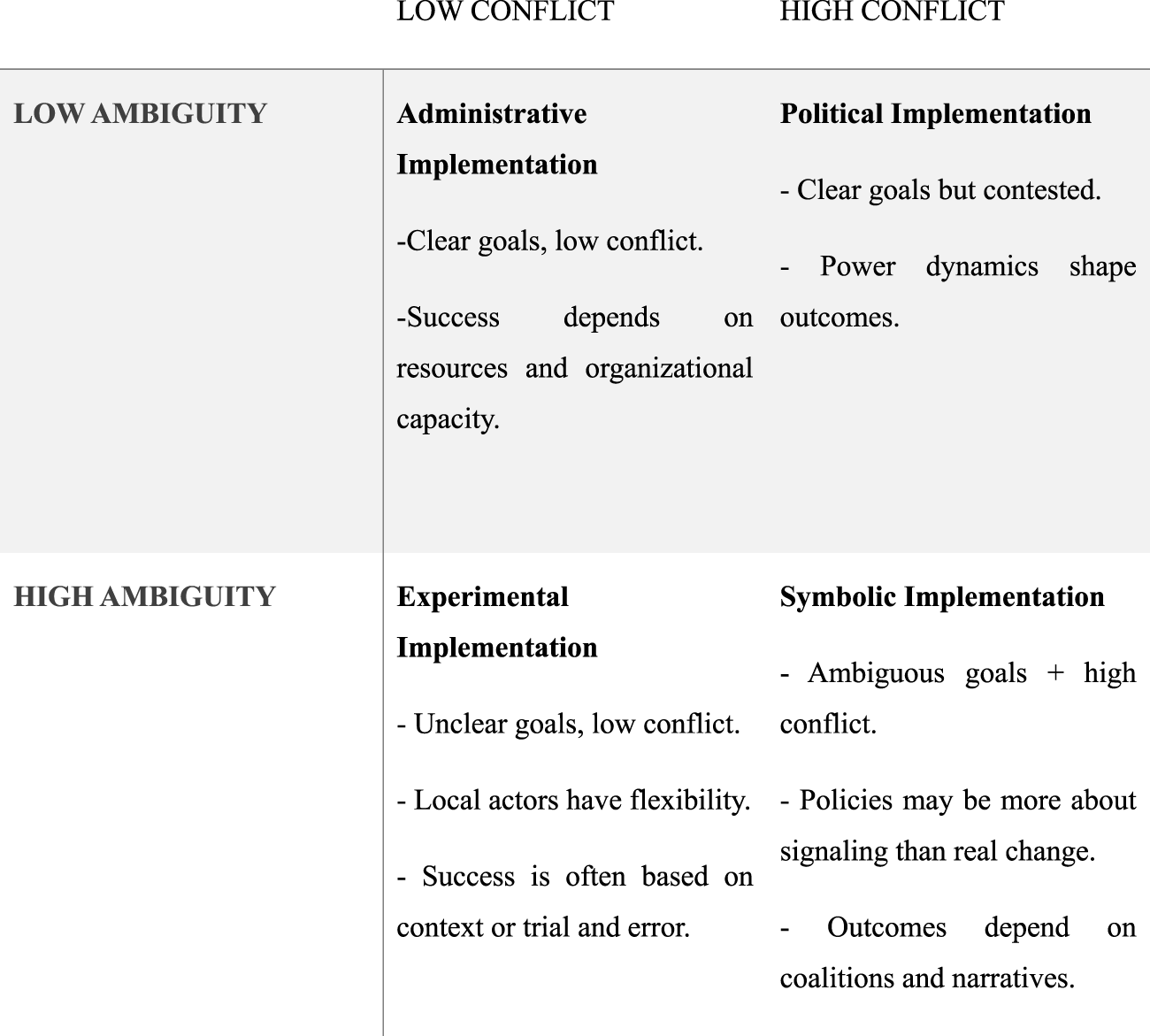

Metland’s Ambiguity-Conflict Model explains policy implementation outcomes based on two key variables of policy ambiguity and policy conflict, as illustrated in Figure 1 (Jensen et al., 2018). The model explains why some policies fail and others succeed during implementation and is applicable to Kenya’s pastoral policy landscape. According to the model, low ambiguity policies have clear goals and means of achieving them, and vice versa. Also, low-conflict policies have high consensus and minimal political contestation, leading to success in implementation and vice versa. Therefore, the success or failure of implementing pastoral policies in Kenya depends on the context of implementation, clarity of goals, and power relations of various power actors.

FIGURE 1

Metland model.

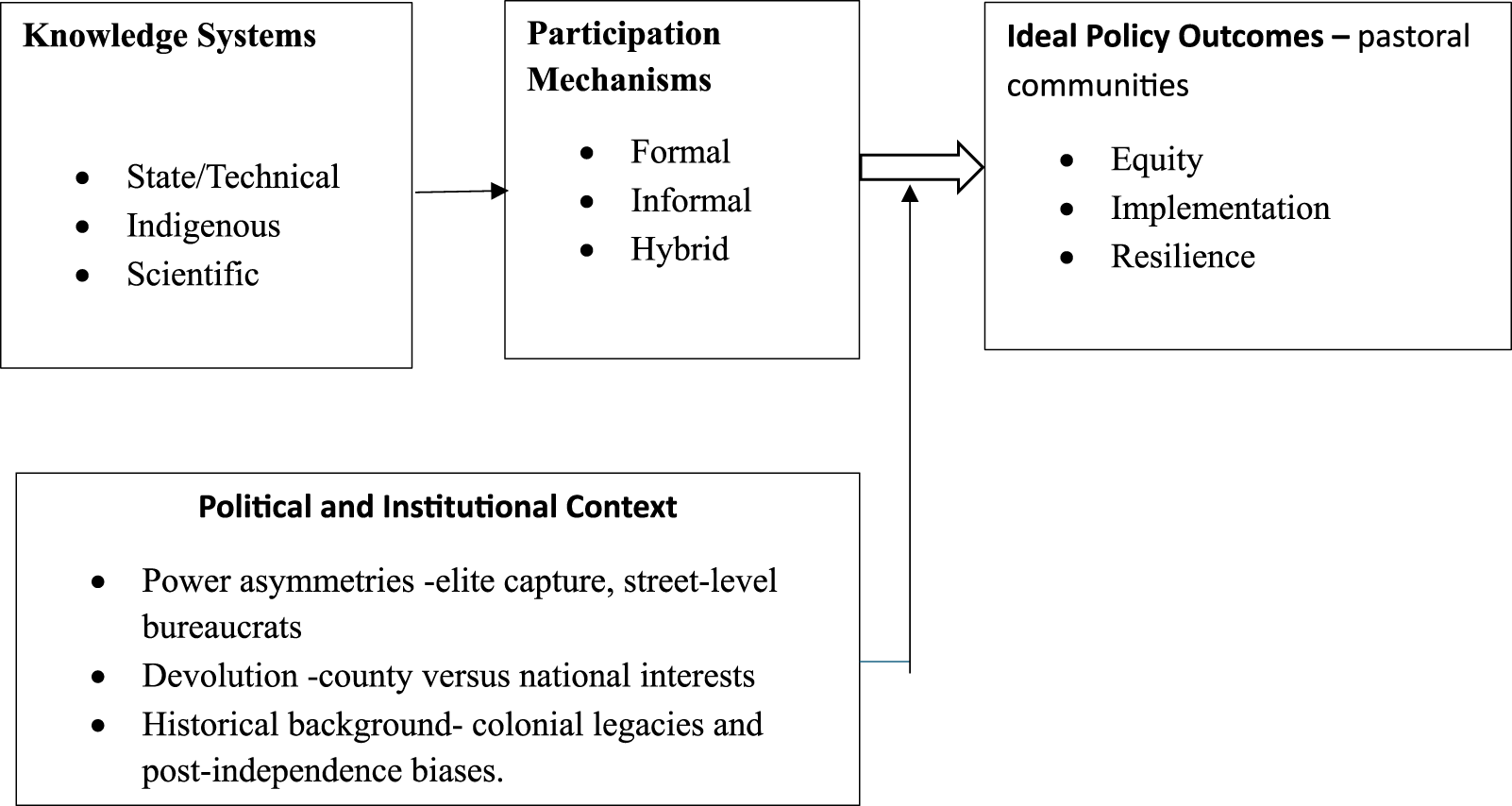

The conceptual framework illustrates how knowledge systems, participation mechanisms, and policy outcomes interact within a broader political institutional context (Figure 2). Arrows show the flow from knowledge (state, indigenous, scientific) to participation (formal, informal, hybrid), ultimately shaping outcomes (equity, implementation, and resilience). The bottom box highlights external factors like power asymmetries and historical marginalization that either distort or enhance this process. This model clarifies why policies fail pastoralists: when knowledge is exclusionary, or participation is tokenistic, outcomes reinforce inequality rather than resilience.

FIGURE 2

Conceptual framework.

Materials and methods

This qualitative policy analysis evaluates Kenya’s pastoral policies through the lens of the African Union Pastoralism Framework assessing governance structures, formulation processes, and implementation alignment (African Union, 2010). The study analyzes primary legal/policy documents, including Kenya’s Constitution, CIDPs, National Livestock Policy, Community Land Act, and IGAD Transhumance Protocol alongside secondary data from, Kenya Law Reform Commission (KLRC), Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA) and International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) (GoK, 2010b; GoK, 2020b; GoK, 2016a; IGAD, 2020a). County-level cases (e.g., Marsabit, Turkana, Isiolo CIDPs) illustrating the impacts of devolution.

Using a political economic approach, the research examines power dynamics, historical marginalization, and institutional capacity, focusing on land rights, mobility, gender equity, market access, and climate adaptation. It critiques public participation, budgeting, and intergovernmental coordination, triangulating documentary analysis, policy evaluations, and county case studies. The study, approved by national and university ethics committees, identifies gaps in Kenya’s alignment with AU goals and proposes actionable improvements for pastoral development.

Results and discussion

Policy formulation and pastoral policies in Kenya

Kenya’s policy-making process is a structured, multi-stage approach emphasizing inclusivity, transparency, and alignment with development agendas (KLRC, 2015; KIPPRA, 2021). It involves initiation by government and stakeholders, followed by research, consultations, public participation, and approvals before publication or legislative drafting. Similarly, the legislative process requires gazettement, public input, multiple readings, committee reviews, and assent by the President or Governor, ensuring scrutiny, accountability, and coordination across national and county levels (KLRC, 2015; KIPPRA, 2021).

Key frameworks addressing pastoralism in Kenya

Kenya has established various frameworks to support pastoralism, guided by the Constitution and regional agreements. Policies like the National Policy for Development of ASALs integrate pastoralists into education and health while addressing women’s vulnerabilities, while the National Food and Nutrition Security Policy enhances productivity and drought resilience (GoK 2012c; GoK, 2011). The National Peace Building Policy tries to resolve pastoralist-agropastoral conflicts through stakeholder participation (GoK, 2014). However, implementation gaps persist, Vision 2030s, Medium Term Plans (MTPs) lack explicit pastoralist strategies, and laws like the Community Land Act and National Land Use Policy face weak enforcement (GoK, 2010b; GoK, 2013; GoK, 2022a; GoK, 2016a; GoK 2017c; GoK, 2008; GoK, 2013; GoK, 2022a).

Recent policies, such as the National Livestock Policy, recognize pastoralism’s economic role, proposing better land use and market access (GoK, 2020b). Complementary frameworks like the Gender Policy, Livestock Act, and IGAD Transhumance Protocol address gender disparities and cross-border mobility (GoK 2019b; GoK, 2021a; IGAD, 2020a). County initiatives, including Rangelands Strategies, further support pastoralism (GoK, 2021b). Despite progress, devolution’s success hinges on stronger funding, coordination, and political will to bridge implementation gaps. The ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and County Governments spearhead these efforts, with policies summarized in Table 1 for reference (Ministry of AgricultureLivestockFisheries and Irrigation, 2019). For ease of reference, these major policies and legislation are organized by the governing body as high lightened in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Governing body | Key policies |

|---|---|

| The Agriculture Sector Coordination Units of the county governments and the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries, and Cooperatives (MoALF&C) | National Livestock Policy, National Food and Nutrition Security Policy, National Livestock Policy 2020, Rangelands Management and Pastoralism Strategy, Agricultural Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy |

| Ministry of National Treasury and Planning (MTP) | Medium Term Plans |

| Northern Kenya and Development Ministry of State | The ASAL Policy is Kenya’s National Policy for the Sustainable Development of Arid and Semi-Arid Lands |

| Ministry of Lands and Physical Planning | National Land Use Policy |

| Ministry of Public Service, Youth and Gender | National Policy on Gender and Development |

| County Ministries of Pastoralism and Livestock Production Pastoralist Parliamentary Group, Senate | County Integrated Development Plans |

Pastoral policy and governance.

County landscape

Kenya’s Constitution introduced devolution in 2013, decentralizing power and resources from the national government to forty-seven counties to enhance governance, equitable development, and service delivery (GoK, 2010a; GoK 2012a). The Fourth Schedule delineates county functions, empowering them to legislate and implement policies in health, agriculture, and trade. While devolution has boosted local decision-making, challenges like funding gaps, capacity constraints, low absorption rates and intergovernmental disputes persist. Institutions like the Council of Governors (CoG) and the Intergovernmental Relations Act, aim to improve coordination, but success hinges on counties' administrative capacity and political commitment (GoK 2012b; GoK 2020a).

Kenya’s Arid and Semi-Arid Lands spanning twenty-two counties, including Turkana, Marsabit, and Mandera are home to pastoralist communities. Regions like Narok, Kajiado, and Laikipia also rely on livestock production. These areas face climate vulnerabilities, with Table 2 illustrating the overlap between geopolitical and historically marginalized and underdeveloped Northern Kenya, livelihood based pastoral zones, and broader climatic and ecological classification ASALs each with distinct but complementary policy implications.

TABLE 2

| Northern Kenya | Pastoral areas | ASALs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Counties | Turkana, parts of Baringo, West Pokot, Samburu, Isiolo, Marsabit, Mandera, Wajir, Garissa, Tana River, Lamu | Turkana, Baringo, West Pokot, Samburu, Isiolo, Marsabit, Mandera, Wajir, Garissa, Tana River, Narok, Kajiado, parts of Laikipia | Turkana, Baringo, West Pokot, Samburu, Isiolo, Marsabit, Mandera, Wajir, Garissa, Tana River, Narok, Kajiado, Lamu, Kilifi, Kwale, Taita Taveta, Kitui, Makueni, Meru, Tharaka-Nithi, Embu, Laikipia |

Classification of counties by different dryland categories.

Comparative assessment of Kenya’s pastoral policies against the African Union framework

Efforts to support African pastoral communities focus on securing their livelihoods, rights, and integration into broader economic development. Key strategies aim to recognize the vital role of pastoralism in national economies and strengthen indigenous institutions and women’s participation. These strategies also promote climate adaptation, mobility, and innovative service delivery models tailored to the unique needs of pastoralists. Additionally, protecting pastoral assets, securing property rights, and enhancing livestock marketing and financial services are central to reinforcing the contribution of pastoralism to regional and continental development. Table 3 below identifies three objectives of the AU Framework for pastoralism and the respective strategies to be pursued to achieve each of the objectives. The strategies talk to recognizing and incorporating pastoralism and pastoral activities as a national economic growth enabler.

TABLE 3

| Objective | Strategies |

|---|---|

| Objective 1: Secure and protect the lives, livelihoods, and rights of pastoral peoples and ensure continent wide commitment to the political, social, and economic development of pastoral communities and pastoral areas | 1.1. Recognize the role of pastoralists in national economic development |

| 1.2. Commit to funding pastoral development | |

| 1.3. Integrate pastoralism in development sectors | |

| 1.4. Legitimize Indigenous pastoral institutions | |

| 1.5. Strengthening women’s rights in pastoral communities | |

| 1.6. Integrate pastoral issues into poverty reduction | |

| 1.7. Improve mobile service delivery in pastoral communities | |

| Objective 2: Strengthen the role that pastoral cattle play in the economies of the country, the region, and the continent | 2.1. Secure pastoral property rights |

| 2.2. Support mobility within and between countries | |

| 2.3. Protect pastoral livestock assets | |

| 2.4. Improve marketing of livestock and products | |

| 2.5. Promote financial and insurance services | |

| 2.6. Protect African genetic resources | |

| 2.7. Strengthen research and extension |

Policy Overview Aligned to AU Framework for Pastoralism.

Source: African Union (2010) Policy Framework for Pastoralism in Africa.

Let’s now turn to discussing each of two objectives identified in Table 3 below. We sought to know, how does the Government of Kenya (GoK) policies and legislation as high lightened stand with respect to these AU specific objectives and strategies in Table 3? We have summarized our answers in Table 4 starting with Objective 1: Secure and protect the lives, livelihoods, and rights of pastoral peoples and ensure continent-wide commitment to the political, social and economic development of pastoral communities and pastoral areas. Table 6 focusing on objective 2: Strengthen the role that pastoral cattle play in the economies of the country, the region, and the continent. The text that follows Tables 4, 6 explains our findings with respect to each strategy under objectives 1 and 2. In particular, the reasons for evaluative terms, like weak, unfavorable and moderate in Tables 4, 6 are outlined in the text.

TABLE 4

| Strategy | Policy rationale | Implementation rationale | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1. Recognize pastoralism in economic development | Moderate: The pastoral county government recognizes the importance of pastoralism in county-integrated development plans; however, institutional frameworks support commercial ranching | Weak: Delays in the design of policies (e.g., the ASAL Policy) affect implementation plans | Favorable policy, weak implementation or moderately favorable policy, moderate to weak implementation |

| 1.2. Commit to funding pastoral development | Unfavorable: Pastoral counties rely on insufficient government funding, and regional governments misappropriate donor funds allocated to pastoral projects | Weak: Policies lack continuity in pastoral institutional dockets as ministries responsible for pastoral issues were disbanded | Unfavorable policy, weak implementation, or unfavorable policy |

| 1.3. Integrate pastoralism in development sectors | Moderate: CIDPS are enacted with pastoral representatives in mind, considering their cultures and traditions | Limited evidence: Limited information demonstrates the implementation of inclusive participation of pastoralists in development projects | Limited or no evidence |

| 1.4. Legitimize Indigenous pastoral institutions | Favorable: ASAL policy acknowledges pastoralists' traditional systems of governance and administration, while CIDPs acknowledge the importance of pastoralists as custodians and stakeholders of natural and cultural resources | Limited evidence: Limited information on how implementation strategies offer an assessment of the role played by clan elders in deciding political leadership against the individual’s rights in the electoral process | Limited or no evidence |

| 1.5. Strengthening women’s rights in pastoral communities | Favorable: The Constitution acknowledges injustice against women; the National Land Use Policy seeks to ensure women’s rights are protected in rangeland management, while the ASAL policy aims to ensure that finance is available to women and women livestock producers | Weak: The pastoral county government failed to formulate an own-source revenue policy, considering that women own businesses in hides and skins, charcoal, and firewood. Women are also weakly represented in county positions | Favorable policy, weak implementation or moderately favorable policy, moderate to weak implementation |

| 1.6. Integrate pastoral issues into poverty reduction | Moderate: The Food and nutrition security are addressed in the Constitution and Kenya Vision 2030, which also promotes the inclusive involvement of pastoralists in reaching middle-income status | Weak: Because pastoral areas' Human Development Index has stayed below the national average, the county government has not implemented policies and practices. In the face of poverty, pastoralists continue to maintain sizable herds of animals to ensure their survival during droughts | Favorable policy, weak implementation, or moderately favorable policy, moderate to weak implementation |

| 1.7. Improve mobile service delivery in pastoral communities | Favorable: ASAL policy targeted establishing health insurance while the government established NACONET to cater to pastoralists' mobility nature | Weak: Illiteracy in Garissa County is about 8%, while the distance to the nearest health facility is estimated at 20 km around settlements | Favorable policy, weak implementation, or moderately favorable policy, moderate to weak implementation |

| Addendum strategy 1.8. Emphasize the importance of climate adaptation and resilience | Moderate: ASAL policy, rangeland management, and pastoralism strategy address the issue of droughts, providing opportunities for communities to benefit from carbon trading | Limited evidence: Limited information exists on the budgetary and capacity for implementing the policy objectives | Limited or no evidence |

Summary of Evaluation of Kenya’s pastoral policies against the AU pastoral policy framework.

Source: Policy Framework for Pastoralism in Africa, (African Union, 2010). As per the author’s scoring.

Objective 1- securing and protecting the lives, livelihoods, and rights of pastoral peoples and ensuring continent wide commitment to the political, social, and economic development of pastoral communities and pastoral areas

The main sub-objectives of Kenya’s pastoral development policies are to address the difficulties faced by pastoral communities and to acknowledge the contribution of pastoralism to economic growth. While the policy environment is generally favorable or moderately supportive, there are significant gaps in policy implementation due to weak institutional capacity, limited resources, and poor coordination. Challenges such as weak funding mechanisms, limited inclusion of indigenous institutions, and poor service delivery hinder the realization of these objectives. Despite progressive policy frameworks, the implementation of pastoral development strategies remains weak or uneven across key sectors.

Strategy 1.1 recognize the role of pastoralism in development

The overall scoring of strategy 1.1 is either a favorable policy with weak implementation or moderately favorable policy with moderate to weak implementation. East Africa’s traditional livestock sector supplies 90% of meat consumed (Nyariki and Amwata, 2019), yet policies favor commercial ranching (Odhiambo, 2021). While Kenya’s ASAL policy aligns with the AU Pastoralism Framework, implementation lags, as seen with delays in the ASAL Policy draft (CSDES, 2016; GoK 2012c). Political marginalization persists, exemplified by disputed 2009 census data in pastoralist counties (KHRC, 2018).

County governments recognize livestock’s economic but face challenges like overgrazing and unproductive labor (Isiolo County Government, 2018). Policymakers lack disaggregated rangeland data, hindering capacity-building (Odhiambo, 2021). Though county plans integrate pastoralist rights, awareness of pastoralism’s developmental role, particularly in budgeting, remains inadequately documented among stakeholders.

Strategy 1.2 commit to funding pastoral development

Strategy 1.2 overall scoring is either an unfavorable policy coupled with weak implementation, or summative unfavorable policy. Kenya’s Constitution mandates that 15% of national revenue be allocated to counties (GoK, 2010a), supplemented by local sources. However, some counties like Turkana generate only 1%–2% locally and remain heavily dependent on central funds (County Government of Turkana, 2019). Supplemental funds like the Equalization Fund and Northern Kenya Investment Fund (per ASAL Policy) represent important avenues for addressing regional disparities. Continued efforts to operationalize these instruments through well-defined implementation frameworks could further enhance their impact and alignment with local development priorities.

Institutional frameworks supporting arid and semi-arid lands have evolved over time. These include the former Ministry for Northern Kenya (Odhiambo, 2021) and the Ministry of Devolution, which has played a central role in decentralization. Earlier initiatives such as the $223.9 million Arid Lands Resource Management Project (ALRMP), supported by the World Bank, reflect significant investment in the region (AFRICOG, 2012). More recently, the establishment of ministries such as the Ministry of East African Community (EAC) and ASALs signals continued commitment to addressing the needs of pastoralist communities. The budget process also incorporates pastoralism through the Commission on Revenue Allocation’s (CRA) formula (CRA, 2021), and constitutional provisions mandate resource transfers when functions shift between levels of government (GoK, 2010a). Nonetheless, ensuring sustained institutional presence and coordination in rangeland development remains an area with room for further strengthening.

Strategy 1.3 integrate pastoralism in development sectors

The overall scoring of strategy 1.3 is either limited or there is no evidence. County Integrated Development Plans across Kenya’s pastoral regions acknowledge pastoralism’s economic significance and have created localized strategies to enhance pastoralist resilience. These plans focus on key areas including livestock productivity, market development, animal healthcare, conflict mitigation, and climate adaptation measures. However, implementation faces persistent challenges including limited funding, low literacy rates, and intercommunal conflicts.

Specific counties have adopted tailored approaches: Turkana, Marsabit, and Mandera emphasize capacity building through education programs, and emergency response systems. Meanwhile, Isiolo and Wajir counties concentrate on securing land tenure rights and modernizing pastoral practices to bridge traditional livelihoods with commercial opportunities. Despite these efforts, structural barriers continue to constrain the full integration of pastoralism into sectoral development. Table 5, which includes the sixteen major pastoral counties in Kenya, gives the overall inclination of their respective CIDPs towards pastoralism.

TABLE 5

| Turkana: Dedicated to enhancing the capacity of pastoralists through capacity building, training, education, reducing conflicts, and improving market infrastructure, livestock production, and animal health | Marsabit: Pastoralism is the main income-generating opportunity. The country plans to improve resilience by improving disaster management, disease control, veterinary service extension, etc. |

| Samburu: Priorities include enhancing pastoral resilience through education, rangeland, and soil management, improving emergency response, and peace among communities | Mandera: Improve pastoral resilience through improved emergency responses, climate change mitigation, livestock production, infrastructure, animal health, and marketing |

| West Pokot: Plan to enhance pastoral resilience by improving natural resources management, market access, and trade and livelihood support for pastoralists' management | Wajir advocates modernizing pastoralism and preserving traditional culture by adapting commercial lenses to improve their livelihoods and generate significant wealth |

| Laikipia Advocates improve livestock production through inputs, feedlots, animal health, and market linkages and create mobile clinics to ensure pastoral communities are reached | Isiolo: Besides aiming to enhance pastoralists' resilience by improving livestock production, infrastructure, and animal health, the Isiolo County government is advocating land tenure rights for pastoralists |

| Narok: Ongoing projects to enhance the resilience of pastoral communities through livestock infrastructure projects, rangeland management, and breed improvement | Garissa: Have prioritized policies to increase emergency responses, improve community preparedness, resilience, and adaptation to climate change, and revamp livestock production |

| Kajiado: The aim is to provide extension services to pastoralists through vocational schools, improve infrastructure rangeland management, and eventually build capacity to improve livestock production | Tana River: Dedicated to improving livestock production, marketing, drought resilience, breeding, and animal health, and well adapted to pastoral production systems |

| Baringo: commits to supporting pastoralism by enhancing livestock production, improving rangeland management, strengthening livestock markets, and promoting drought resilience to sustain pastoral livelihoods | Taita Taveta: commits to supporting pastoralism by enhancing livestock production, improving market access, and strengthening rangeland management to boost pastoral livelihoods and resilience |

| Lamu: supporting pastoralism through improved livestock markets, water infrastructure, and conflict-resolution mechanisms to enhance pastoral livelihoods and resilience | Elgeyo Marakwet: improved livestock value chains, water infrastructure development, and climate-resilient rangeland management to enhance pastoral livelihoods |

County Integrated Plans and their Commitment to Support Pastoralism.

The sixteen counties in Table 5 are part of Kenya’s ASAL and pastoral zones where livestock-based livelihoods are central. The counties reflect diverse pastoral contexts across the country and have CIDPs that prioritize improving livestock production, market access, rangeland management, and resilience to climate change. Since CIDPs are key planning tools under devolution, analyzing them helps assess county-level commitment to supporting and modernizing pastoralism.

Strategy 1.4 legitimize indigenous pastoral institutions

Under strategy 1.4, there is limited or no evidence on legitimizing indigenous pastoral institutions. ASAL policy acknowledges the traditional systems of governance and administration in a pastoral society (GoK, 2012c). National Peace Building and Conflict Management Policy (GoK, 2014) considers pastoral policies and their role in governance, alternative dispute resolution, human-wildlife conflict, and sustainable peace and security with neighboring countries. County Integrated Development Plans (CIDPs) in pastoral areas recognize pastoralists as custodians and stakeholders of natural and cultural resources. However, there is limited information on how implementation strategies offer an assessment of the role played by clan elders in deciding political leadership against the individual’s rights in the electoral process (Odhiambo, 2021). There is also limited information on how the resultant political leadership drives coalition, which is important in policy implementation.

Strategy 1.5 strengthening women’s rights in pastoral communities

Our overall evaluation of strategy 1.5 is either favorable policy and weak implementation or moderately favorable policy with moderate to weak implementation. Kenya’s National Policy on Gender and Development promotes sustainable women’s empowerment, yet implementation through County Integrated Development Plans (CIDPs) remains inconsistent in pastoralist regions (GoK, 2019b). While women constitute substantial populations, from estimated 78,286 in Isiolo to 771,742 in Mandera (County Government of Marsabit, 2018), these areas show limited gender-specific policies and inadequate maternal healthcare access.

Several policies support women’s rights, including the National Land Use Policy protecting rangeland access and the ASAL Policy ensuring livestock financing (Odhiambo, 2021). Constitutional provisions mandate women’s political representation, resulting in twenty-seven female MPs and mobile schooling initiatives (DLCI, 2021). However, Oxfam (2022) reports persistent challenges: women’s underrepresentation in county governments, exclusion from revenue policy despite their significant economic contributions, and gender-blind (information communication technology) ICT systems.

A critical gap exists between constitutional land rights and local practices in Turkana, where women face inheritance barriers (Akall, 2021), forcing them into risky livelihoods and worsening inequality. This underscores the need for better gender-disaggregated data and evaluation of whether top-down gender-responsive budgeting effectively reduces disparities in pastoralist counties.

Strategy 1.6 integrate pastoral issues into poverty reduction

Overall evaluation of strategy 1.6 is either favorable policy coupled with weak implementation, or moderately favorable policy with moderate to weak implementation. Communities in Turkwell and other pastoral areas have grown increasingly dependent on cash transfers due to dwindling rangeland resources (Akall, 2021). While Kenya’s National Food and Nutritional Security Policy, aims to break poverty cycles through coordinated resource management, its effectiveness remains questionable after 11 years of implementation, given persistent food insecurity (GoK, 2011). Constitutional provisions (Article 10, 2010) and Vision 2030 emphasize sustainable development and inclusive growth, with county governments established to promote equity (GoK, 2010a; GoK 2010a). Programs like the Hunger Safety Net demonstrate these efforts (Garissa County Government, 2018).

Development partners including United Nations (UN) agencies, NGOs, and initiatives like Lamu Port and Lamu Southern Sudan Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET), which promises economic growth through livestock market expansion (Marsabit County Government, 2018), operate across multiple sectors. Despite these interventions, pastoral regions continue to lag in human development indicators, revealing systemic shortcomings. The enduring practice of maintaining large herds as drought insurance underscores the deep rooted cultural and economic logic within pastoral systems. While policy interventions have aimed to support livelihood diversification and resilience, there remains an opportunity to further align these efforts with the adaptive strategies already in use by pastoral communities, particularly in the context of persistent vulnerability and poverty.

Strategy 1.7 improve mobile service delivery in pastoral communities

Strategy 1.7 is evaluated as either a favorable policy with weak implementation, or moderately favorable policy with moderate to weak implementation. Kenya established National Council for Nomadic Education in Kenya (NACONEK) in 2015 to address pastoralists' educational needs (GoK, 2019c), while the ASAL Policy aims to create tailored health insurance (GoK, 2012c). However, pastoral regions still face significant challenges. Garissa County illustrates these issues starkly: residents travel an average 20 km to health facilities, with severely inadequate medical staffing (1 doctor per 41,538 people versus WHO’s 1:10,000 standard) (Garissa County Government, 2018). The county suffers from high malnutrition rates and extreme literacy gaps - only 8.2% literacy overall, with 74% illiteracy and significant gender disparities (Garissa County Government, 2018). These conditions persist despite policy interventions, revealing critical implementation gaps in serving mobile pastoralist communities.

Addendum strategy 1.8: emphasize the importance of climate adaptation and resilience

Addendum strategy 1.8 is evaluated as limited or has no evidence. The added strategy is not within the AU Framework but based on the relevance and implications of climate change to pastoralism, we included it for review. Kenya’s ASAL policy mandates creation of a National Drought Management Authority and Disaster Contingency Fund, while also enabling pastoralist communities to participate in carbon markets (Odhiambo, 2021; GoK, 2016b). The 2021 Range Management Strategy further develops frameworks for drought prediction and rangeland conservation through early warning systems to boost climate resilience (GoK, 2021b). However, implementation challenges persist due to unclear budgeting and insufficient capacity to execute these policy goals.

Objective 2- strengthen the role that pastoral cattle play in the economies of the country, the region, and the continent

Kenya’s pastoral policy framework establishes multiple objectives to strengthen community resilience, including land rights protection, mobility support, livestock security, market access, and climate adaptation (Table 6). Implementation remains uneven - while property rights and livestock protection show notable progress (especially in Isiolo), other areas like mobility, marketing systems, financial services, and genetic resource conservation demonstrate weak or inconsistent execution.

TABLE 6

| Strategy | Policy rationale | Implementation rationale | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1. Secure pastoral property rights | Favorable: Community Land Act recognizes communal land ownership of pastoral rangelands | Strong: Noted improvements in improved pasture in Isiolo County from three thousand acres in 2013 to about five thousand acres in 2017 | Favorable policy, strong implementation |

| 2.2. Support mobility within and between countries | Moderate: IGAD protocol aims to facilitate mobility for herders and livestock | Limited Evidence: Limited information exists on the outcomes of policies regarding mobility for pastoralists | Limited or no evidence |

| 2.3. Protect pastoral livestock assets | Moderate: Kenya Vision 2030 aims to improve pastoral counties' infrastructure by establishing Livestock disease-free zones and regional abattoirs | Strong: Isiolo County has improved animal health services with additional funding to develop climate-tolerant livestock breeds | Favorable policy, strong implementation |

| 2.4. Improve marketing of livestock and products | Favorable: Kenya Vision 2030 and ASAL policy recognize the importance and aim of establishing markets and abattoirs to improve the off take of livestock products in pastoral counties | Weak: Limited positive effects on implementation as market infrastructure projects in Isiolo are incomplete years after the launch of the development plan. Pastoral counties lack market infrastructure, ranches, and feedlots despite the huge livestock population in such counties | Favorable policy, weak implementation, or moderately favorable policy, moderate to weak implementation |

| 2.5. Promote financial and insurance services | Moderate: ILRI rolled out livestock insurance schemes based on the severity of climate change, and Isiolo County is working to implement a Livestock insurance program alongside other private companies | Weak: Despite insurance schemes through ILRI and county governments, they have been inadequate in insuring pastoralists from uncertainties | Favorable policy, weak implementation, or moderately favorable policy, moderate to weak implementation |

| 2.6. Protect African genetic resources | Moderate: The government aims to invest in livestock breeding to improve animal husbandry in Vision 2023 | Limited evidence: The Veterinary Department in Marsabit implements projects to improve animal health services and livestock breeds. However, there is little evidence of the implementation of programs that cater to genetic resources | Limited or no evidence |

| 2.7. Strengthen research and extension | Favorable: County and government policies seek to strengthen research and extension services in pastoral counties; however, policies remain inadequate and lack guidance in gender auditing | Weak: Extension services have been few in pastoral counties, with one research station (Marsabit) and one farmers’ training center (Marsabit and Isiolo) | Favorable policy, weak implementation, or moderately favorable policy, moderate to weak implementation |

| Addendum strategy 2.8: Mitigate emissions and increase resilience through climate adaptive practices | Favorable: Several institutions recognize the importance of climate change mitigation and have committed to ending droughts, improving Rangeland Management, promoting green energy, etc. | Moderate: Despite water resource management infrastructure in Marsabit, boreholes have contributed to drought and rangeland degradation through a siphoning effect on forest water sources. | Favorable policy, weak implementation, or moderately favorable policy, moderate to weak implementation |

Evaluation of Kenya’s pastoral policies against AU pastoral policy framework.

Strategy 2.1 secure pastoral property rights

Strategy 2.1 is evaluated as having a favorable policy with strong implementation. Urban expansion threatens pastoral transhumance and accelerates resource depletion (Akall, 2021). While the Community Land Act recognizes communal land rights, challenges persist in county-level land governance, including political interference and unregistered community lands, despite pastoral rangelands contributing to revenue streams like land rates (OXFAM, 2022). The National Land Use Policy addresses water and pasture scarcity, aiming to curb land fragmentation, urban encroachment, and unplanned rangeland conversion while promoting communal grazing plans and land registration for pastoralists (GoK, 2020b).

County Integrated Development Plans (CIDPs) highlight resource management challenges but show progress in some areas, such as Isiolo, where registered land increased from three hundred acres in 2013 to 5,000 in 2017 (Isiolo County Government, 2018). CIDPs also integrate pastoral concerns into spatial planning and legal frameworks. Finally, the Rangeland Management and Pastoralism Strategy seeks to enforce sustainable rangeland practices across government levels (GoK, 2021b).

Strategy 2.2 support mobility within and between countries

The overall evaluation of strategy 2.2 is limited or has no evidence. The IGAD Protocol on Transhumance aims to facilitate cross-border mobility for herders and livestock (IGAD, 2020a). On the other hand, there is limited evidence about the results of the national and local execution of the policy.

Strategy 2.3 protect pastoral livestock assets

Strategy 2.3 is a favorable policy with strong implementation. Kenya Vision 2030 aimed to establish Livestock Disease Free Zones and regional abattoirs (GoK, 2010b). Isiolo’s county integrated development plan notes key achievements in veterinary services in disease quarantine, regular meat inspections, and improved animal identification (Isiolo County Government, 2018). Additionally, in Isiolo, there exist programs and proposals on strengthening research and extension with partners and institutions on issues on livestock diseases and on development of more climate-tolerant breeds with sources of funding including International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Vétérinaires Sans Frontières (VSF), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), universities, and other development partners and the implementing agent as Veterinary department.

Strategy 2.4 marketing of livestock goods and pastoral livestock

The evaluation of strategy 2.4 is either a favorable policy with weak implementation, or moderately favorable policy with moderate to weak implementation. Kenya’s ASAL policy proposed establishing a Livestock Marketing Board, while Vision 2030 aimed to develop marketing infrastructure to boost meat exports (GoK, 2010b; GoK, 2012c). Despite livestock contributing 50% of agricultural GDP (∼10% of national GDP) (KALRO, 2022), market interventions remain underdeveloped. While some Vision 2030 projects like Thika Highway were completed, key livestock infrastructure lags - Isiolo’s abattoir (planned for 474,000 animals annually) remain in-operational years later (County Government of Isiolo, 2018), with current capacity at just 270,000.

Market access challenges persist, with middlemen undermining value chains, as seen in Turkana fisheries projects (OECD, 2009). Only 50% of Isiolo traders access market information (Isiolo County Government, 2018). The Amaya Triangle Initiative (Baringo, Laikipia, Samburu, Isiolo) seeks to capitalize on regional livestock potential, supported by facilities like the Isiolo Export Abattoir. NRT conservancies have increased traded animals from 20,000 in 2013 to 30,000 in 2017 through USAID/ADB programs (County Government of Isiolo, 2018). However, Marsabit lacks processing capacity despite its livestock wealth, relying mainly on a 200-head feedlot and 55 marketing cooperatives (Marsabit County Government, 2018).

Strategy 2.5 promote financial and insurance services

Strategy 2.5 overall evaluation is either favorable policy with weak implementation, or moderately favorable policy with moderate to weak implementation. The ASAL Policy proposed livestock insurance programs to protect pastoralists. While International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI’s) Index-Based Livestock Insurance, which compensates based on weather conditions-satellite-observed forage conditions, rather than animal deaths and has expanded to Ethiopia (ILRI, 2022) - exists, coverage remains inadequate. Isiolo County is developing a comprehensive livestock insurance program worth KES 260 million, implemented by the Department of Livestock Production with partners including NG and ICG Takaful (County Government of Isiolo, 2018).

Strategy 2.6 protect African genetic resources

Strategy 2.6 overall evaluation is either limited or has no evidence. Investments in cattle breeding are part of Vision 2030 (GoK, 2010b). Indigenous sheep, goats, and cattle make up most of the livestock population in pastoralist areas, particularly in the southern regions that receive higher rainfall. Poor animal husbandry is seen as a contributing factor to degrading rangelands. Projects exist to strengthen veterinary extension services and livestock breed improvement programs, with the Veterinary Department as the implementing agency (Marsabit County Government, 2018).

Strategy 2.7 strengthen research and extension

On strategy 2.7, the evaluation is either favorable policy with weak implementation, or moderately favorable policy with moderate to weak implementation. The ASAL Policy sought to enhance research and extension services in arid regions, yet implementation challenges persist Marsabit County faces extension service gaps due to its vast territory, with only one KALRO research station, a single farmers' training center, and inactive demonstration farms (Marsabit County Government, 2018; Odhiambo, 2021). Similarly, Isiolo County relies on just one central training facility, though its Agriculture Department plans to expand extension services to modern livestock production (Isiolo County Government, 2018). Both counties struggle with insufficient gender-disaggregated data and lack gender audit policies (Marsabit County Government, 2018).

Addendum strategy 2.8 mitigate emissions and increase resilience through climate adaptive practices

The overall evaluation of strategy 2.8 is either a favorable policy with weak implementation, or moderately favorable policy with moderate to weak implementation. Kenya’s National Drought Management Authority committed in 2016 to eliminate drought emergencies (GoK, 2016b), while the National Land Use Policy integrates climate adaptation into rangeland management. A Ksh 961.6 million Climate Smart Agriculture project in Isiolo, funded by National Government (NG), World Bank and partners, aims to enhance livelihoods across all sub-counties (County Government of Isiolo, 2018). However, Marsabit faces challenges as borehole drilling has intensified water source depletion and drought grazing pressures (Marsabit County Government, 2018), highlighting the need for climate-sensitive water management. Pastoral counties are incorporating green energy and ICT into disaster risk policies to strengthen resilience (County Government of Isiolo, 2018).

AU framework process guidelines

Pastoral policy development is inherently complex, requiring participatory and iterative approaches that reflect the diverse realities of pastoralist communities. Section AU framework process guidelines evaluates Kenya’s progress in implementing key steps of the policy development process against AU Framework Process Guidelines that seeks to ensure a robust and inclusive participatory process incorporating pastoralist perspectives and input. The analysis draws on literature and documented evidence to assess the extent to which these steps have been realized, with a focus on inclusivity, institutional capacity, and implementation effectiveness.

Ensure a robust and inclusive participatory process incorporating pastoralist perspectives and input

Kenya’s pastoral policy development process follows structured steps aimed at inclusive participation and good governance. While progress is evident in drafting planning documents like County Integrated Development Plans, implementation faces major hurdles. Key challenges include insufficient community engagement, inadequate funding, weak institutional capacity, and poor information dissemination. The overall process remains hampered by ineffective implementation, lacking evidence of conclusive consultation, defined institutional roles, or successful capacity-building initiatives (Table 7).

TABLE 7

| Steps | Implementation rationale | Overall |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1. Consult pastoralists and other actors to identify key changes | Weak: Implementation highlights the engagement of elite members of society who do not amplify all pastoralists' concerns and are the minority that benefit from government and development partner interventions | Weak implementation |

| 1.2. Prepare working documents for further discussion | Strong: Pastoral counties have developed County Integrated Development Plans linked to the AU Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals | Strong implementation |

| 1.3. Appraisal of institutional and financial/budgetary options | Weak: The budgetary allocation made for pastoral counties is inadequate, and supplemental funds, i.e., the equalization fund and the Northern Kenya Investment Fund, as per ASAL Policy (GoK, 2012c), lack clarity on implementation | Weak implementation |

| 1.4. Iterative process to refine national pastoral policy | Weak: Institutions cannot engage communities in policy development, as they rely on county governments to carry out the task | Weak implementation |

| 1.5. Design implementation program and institutional responsibilities | Limited evidence: Limited information exists on the implementation program and institutional responsibilities | Limited or no evidence |

| 1.6. Enact new or revise/repeal existing pastoral legislation | Limited evidence: Inconclusive evidence on changing existing policies or revising them | Weak implementation |

| 1.7. Disseminate information and build capacity to support implementation | Limited evidence: Limited evidence of dissemination and capacity building to support implementation | Weak implementation |

AU policy framework for pastoralism in Africa.

Consult pastoralists and other actors to identify key challenges

Step 1.1 is evaluated as weak implementation. There is no conclusive evidence on implementation. Development interventions have been seen to marginalize gender, social and economic status, and access to communal resources further, as only a minority can benefit from the government and development partners' interventions (Akall, 2021). Additionally, the engagement of elites in participatory procedures is seen to amplify different concerns of pastoralists (Rodgers, 2021).

Prepare working documents for further discussion

The overall evaluation of step 1.2 is strong implementation. County Annual Development plans acknowledge public participation in governance issues of planning, budgeting, implementation, and monitoring (County Government of Garissa, 2019). However, there is no conclusive evidence of implementation.

Appraisal of institutional and financial/budgetary options

Step 1.3 is evaluated as weak implementation. County Annual Development Plans seem to integrate public participation of the diaspora community to bridge the financial gap (County Government of Garissa, 2019). However, there is no conclusive evidence of implementation.

Iterative process to refine national pastoral policy

On step 1.4, the evaluation is weak implementation. There is no conclusive evidence of implementation. Additionally, the World Bank provides a community engagement policy note on how implementing agencies should ensure community engagement processes; however, there seems to be limited capacity as there is sometimes reliance and assumption that the government has already engaged the communities or cases of implementing agencies enforcing their interests. Therefore, this delays the project’s implementation and delivery and affects future project interventions (World Bank, 2018).

Design implementation program and institutional responsibilities

Step 1.5 is evaluated as limited or has no evidence. There is no conclusive evidence of implementation. There still exists evidence of the exclusion of women and youth. Therefore, a more inclusive approach through commitment by institutions and agencies, funding and training of facilitators, and translation in real time can offer a solution to the implementation program and institutional responsibilities (Rodgers, 2021).

Enact new or revise/repeal existing pastoral legislation

The overall evaluation of step 1.6 is weak implementation. There is no conclusive evidence on implementation. An example of the Community Land Act case is that a study (Akall, 2021) recommends the integration of marginalized communities on their knowledge of adaptation and climate change to ensure resilience and considerations in the implementation of national government plans.

Disseminate information and build capacity to support implementation

About step 1.7, the evaluation is weak implementation. Current evidence fails to demonstrate effective information dissemination for capacity building in pastoral areas. Research indicates successful community land management requires both formal and customary governance structures (Rodgers, 2021). While democratic governments are recognized, more inclusive hybrid systems must integrate pastoralists, communities, and leaders.

Implementation of livestock programs shows uneven progress across Kenyan counties. Marsabit excels in marketing, policy development, insurance programs and water infrastructure. However, Mandera, Samburu and West Pokot struggle with budgetary limitations, technical capacity gaps and policy delays. Despite isolated successes in infrastructure and research, systemic challenges - particularly weak institutions, funding shortages and policy deficiencies - continue to impede consistent implementation.

Table 8 gives a spot check of seven pastoral counties on their implementation achievements for the year 2019 and 2020 as per County Annual Progress Reports, County Annual Development Plans, and Counties Monitoring and Evaluation Units. The achievements show uneven implementation.

TABLE 8

| Counties | Key achievements |

|---|---|

| Marsabit (County Government of Marsabit, 2018) | Development of secondary and primary markets towards trading is estimated at 71,000 cattle, 250,000 sheep, and goats |

| Establishment of livestock markets management committee | |

| Additionally, the county successfully domesticated the National Livestock Policy, which led to the development of a draft management policy. Bill on livestock marketing and commerce at the county assembly level | |

| Construction of Marsabit modern market. | |

| The holding ground for livestock at Segel is still under construction | |

| Insurance asset protection program of an estimated 2,500 households with the support of the National Government | |

| The Kenya Livestock Insurance Program paid out Kenya Shillings 360,000 to 140 beneficiaries in Dukana in North Horr Sub-County | |

| Ongoing research and extension on Livestock Feeding for Human Health (L4H study) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV) by Washington State University, FAO, and UNICEF. | |

| The Livestock department and partners' distribution of certified grass seeds totaling an estimated 3,500 kgs | |

| 11 cooperatives formed along with the livestock value chains | |

| Twelve boreholes were drilled, 29 earth pans were constructed and designed, and the Water Sector Policy and the Marsabit Water and Sewerage Act of 2018 were developed | |

| Development of climate change adoption action plan | |

| Mandera (County Government of Mandera, 2020; Mandera County Government, 2018) | Lack of policy framework for peacebuilding and conflict management |

| No policies were drafted, bills were enacted due to delays by the county assembly, and no policy on culture and heritage due to budgetary allocation | |

| Low recorded figures of public participation forums at 2 compared to a baseline of 20 | |

| Challenges include the need for more technical staff to implement programs | |

| Targets on livestock health and market infrastructure were constructed, coordination of livestock-based meetings was achieved, and a new abattoir was constructed | |

| Budgetary constraints affected the value of livestock production, animal husbandry, breeding and feeding, dissemination of information on livestock production, livestock investments for groups, and resilience through insurance | |

| West Pokot (County Government of West Pokot, 2021) | Ongoing projects on the introduction of livestock breeds and livestock marketing groups trained |

| Budget absorption of livestock production and management of rangelands was at 0% as of the first quarter of the financial year 2021–2022 | |

| Samburu (County Government of Samburu, 2019) | Delay in funding affects the implementation of programs |

| An estimated Kenya Shillings 5,000,000 is budgeted for formulating county land policy, and another Kenya Shillings 5,000,000 for implementing national urban policy in the county | |

| Another estimated 15,000,000 is for malnutrition, 30,000,000 for enhancing public participation, and 3,000,000 for handling disaster risk and reduction | |

| Isiolo (County Government of Isiolo, 2019) | A notable improvement in livestock record keeping, incidences of zoonotic diseases, and public participation |

| Reduced number of livestock buyers from Isiolo due to distance, competition, and reduction of livestock breeding programs | |

| Challenges in locally processed livestock feed due to costs, market, and competition from agro vets | |

| Policy on County disaster risk management at the final stage | |

| Turkana (County Government of Turkana, 2019) | Lack of policies on development projects and policy research papers and reports disseminated |

| Limited budget for the export market for county products and modernization of markets | |

| Evidence of increased public participation forums held from 32 to 40, pastoralists beneficiaries of livestock extension services at 4,957 from a target of 5,000 | |

| Garissa (County Government of Garissa, 2019) | Strategies for ensuring diaspora stakeholder forums to ensure implementation of initiatives for counties |

| Draft livestock bills, sectoral plans, and rangeland management policies are among the bills forwarded to the county assembly | |

| Zero recorded achievements in training livestock traders and several livestock yards constructed as of June 2018 |

Key achievements of county integrated development plans.

Conclusion and recommendations

The pastoral policy landscape in Kenya reflects progress and persistent challenges in aligning national and county-level frameworks with the needs of pastoralist communities. While devolution under the Constitution of Kenya has provided an opportunity for localized policymaking, implementation remains uneven due to structural, financial, and governance constraints (GoK, 2010a). The African Union 2010 Policy Framework on Pastoralism offers a blueprint for securing pastoral livelihoods (African Union, 2010). However, Kenya’s policies often fail in execution, particularly in mobility rights, conflict resolution, and gender equity.

Despite progressive legal frameworks like the Community Land Act and the National Livestock Policy, pastoralists face marginalization due to historical biases, weak enforcement, and competing land-use interests. Additionally, while County Integrated Development Plans (CIDPs) acknowledge pastoralist needs, elite capture, limited public participation, and insufficient funding often undermine their effectiveness.

A critical gap remains in pastoralists' inclusive participation in policymaking. Although policies such as the ASAL Policy and the National Gender and Development Policy advocate for pastoralist representation and women’s empowerment, implementation is often top-down, with minimal grassroots engagement. Furthermore, though present in policy documents, climate adaptation strategies lack sufficient budgetary support and localized action plans, leaving pastoralists vulnerable to increasing droughts and resource conflicts.

Kenya must adopt a holistic, participatory, and regionally aligned approach to pastoral governance to bridge the gap between policy intent and outcomes. First, there is a need to harmonize national and county policies with the AU Framework, ensuring mobility rights, conflict resolution mechanisms, and climate resilience are prioritized. This requires stronger intergovernmental coordination and dedicated funding mechanisms like the Equalization Fund to address historical underinvestment in ASAL regions. Second, decentralized decision-making must be reinforced by enhancing county governments' capacity to implement CIDPs effectively. This includes increasing budgetary allocations, improving technical expertise, and ensuring meaningful pastoralist participation in policy formulation. Third, gender-responsive policies must move beyond rhetoric by enforcing land inheritance rights, expanding women’s access to livestock markets, and integrating gender audits into county planning processes.

Fourth, livestock marketing and trade policies should be revised to facilitate informal cross-border trade, reduce taxation barriers, and improve infrastructure such as abattoirs and disease-free zones. Finally, robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms must be institutionalized to track policy outcomes, ensuring accountability and adaptive management in response to emerging challenges. Pursuing the four aspects will offer clarity and enhance consensus in pastoral policy implementation, increasing the chances of success.

Kenya’s pastoralist communities remain a vital yet underutilized economic asset, contributing significantly to food security and national GDP. However, without concerted political will, equitable resource allocation, and inclusive governance, existing policies risk remaining symbolic rather than transformative. By aligning with the AU Framework, strengthening devolved governance, and prioritizing pastoralist agencies in policymaking, Kenya can transition from fragmented interventions to a sustainable, resilient pastoral economy that benefits local livelihoods and national development goals. The time for policy coherence and decisive action is now. Pastoralists cannot afford another decade of marginalization amidst climate crises and economic shifts. Kenya must seize the opportunity to redefine pastoral governance, ensuring that policies are written and lived realities for millions who depend on rangelands for survival and prosperity.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SN oversaw the conceptualization of the research idea, methodology design, design, project administration and supervision. AW developed the original manuscript and editing. SB-M contributed to visualization and manuscript development. AM contributed to editing and reviewing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

Author AM was employed by Boston Consulting Group.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

References

1

African Union (AU) (2010). Policy framework for pastoralism in Africa: securing, protecting, and improving the lives, livelihoods, and rights of pastoralist communities. Addis Ababa Afr. Union.

2

African Union. (2013). Policy framework for pastoralism in Africa: securing, protecting and improving the lives, livelihoods and rights of pastoralist communities.

3

AFRICOG (2012). Kenya's drought cash cow. Lessons from the forensic audit of the World Bank arid lands resource management project. Nairobi: Africa Centre for Open Governance.

4

AkallG. (2021). Effects of development interventions on pastoral livelihoods in Turkana County, Kenya. California: Springer.

5

AmesoE. A.BukachiS. A.OlungahC. O.HallerT.WandibbaS.NangendoS. (2018). Pastoral resilience among the Maasai pastoralists of Laikipia County, Kenya. Land7 (2), 78. 10.3390/land7020078

6

BerhanuW. (2016). Informal cross-border livestock trade restrictions in eastern Africa: is there a case for free flows in Ethiopia-Kenyan borderlands?Ethiop. J. Econ.25 (1), 95–119.

7

CatleyA.LindJ.ScoonesI. (2013). Pastoralism and development in Africa: dynamic change at the margins. London: Taylor and Francis, 328.

8

County Government of Isiolo (2018). County Integrated Development Plan 2018-2022. Nairobi: County Government.

9

County Government of Garissa (2019). Eighth Garissa county annual development plan 2020/2021. Garissa: Government Printer.

10

County Government of Isiolo (2019). County annual progress report (CAPR) 2018/19. Isiolo: County Government.

11

County Government of Mandera. (2020). County annual progress report (2019–2020). Nairobi: ministry of finance and economic planning. Department of economic planning and statistics. Monitoring and evaluation section.

12

County Government of Marsabit (2018). County annual progress report (C-apr) FY 2018/19. Marsabit: Government Printer.

13

County Government of Samburu (2019). Annual development plan (2020–2021). Samburu: County Government.

14

County Government of Turkana (2019). County annual development plan (CADP) 2020/2021. Turkana Turkana Cty.

15

County Government of West Pokot (2021). First quarter progress report for FY 2021–2022. Nairobi: County Monitoring and Evaluation Unit.

16

CRA (2021). Technical report of the third basis on revenue sharing among county governments for financial year 2020/21 to 2024/25. Nairobi: Commission on Revenue Allocation.

17

CSDES (2016). Kenya: country situation assessment working paper: pathways to Resilience in Semi-arid Economies (PRISE) project. Canada: The Center for Sustainable Dryland Ecosystems and Societies.

18

DLCI (2021). Drylands learning and capacity building initiative. Available online at: https://dlci-hoa.org/ppg/overview.

19

Garissa County Government (2018). County integrated development plan 2018–2022. Nairobi: County Government.

20

GoK (2008). First medium-term plan 2008–2012. Nairobi: The National Treasury and Planning. State Department for Planning.

21

GoK (2010a). The constitution of Kenya. Nairobi: Government Printer.

22

GoK (2010b). Kenya vision 2030. Nairobi: Government Printer.

23

GoK. (2011). National food and nutrition security policy. Nairobi: agricultural sector coordination unit (ASCU).

24

GoK (2012a). County government Act No. 17. Nairobi: Government Printer.

25

GoK (2012b). The intergovernmental relations Act. Nairobi: Government Printer.

26

GoK (2012c). National policy for the sustainable development of arid and semi-arid lands (ASALs). Nairobi: Government Printer.

27

GoK. (2012d). Sessional paper No. 8 of 2012 on national policy for the sustainable development of northern Kenya and other arid lands 'releasing our full potential.' nairobi: ministry of state for development of northern Kenya and other arid lands.

28

GoK (2013). Second medium-term plan 2013–2017. Nairobi: The National Treasury and Planning. State Department for Planning.

29

GoK (2014). National peace building and conflict management policy. Nairobi: Government Printer.

30

GoK (2016a). Community land Act. Nairobi: Government Printer.

31

GoK (2016b). “The national drought management authority Act,” in National Council for law reporting. Nairobi: Government Printer.

32

GoK (2017a). Guidelines for preparation of county integrated development plans (revised). Nairobi: Ministry of Devolution.

33

GoK. (2017b). National land use policy. Nairobi: ministry of lands and physical planning.

34

GoK (2017c). Sessional paper No. 01 of 2017 on national land use policy. Nairobi: Ministry of Lands and Physical Planning.

35

GoK (2019a). Agricultural Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy 2019–2029: towards sustainable agricultural transformation and food security in Kenya. Nairobi: Ministry of Agriculture. Livestock, Fisheries and Irrigation.

36

GoK (2019b). National policy on gender and development. Nairobi: Ministry of Public Service. Youth, and Gender.

37

GoK (2019c). “Transformative innovation learning history: nomadic education in Kenya: a case study of mobile schools in Samburu county, as a transformative innovation policy,”. Nairobi: National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation.

38

GoK (2020a). Legislative process. From county governance toolkit. Available online at: https://knowledgehub.devolution.go.ke/kh/devolution/county-governance-toolkit/legislative-process/.

39

GoK (2020b). National livestock policy. Nairobi: Ministry of Agriculture. Livestock, Fisheries, and Cooperatives.

40

GoK (2021a). Livestock Act. Nairobi: Government Printer.

41

GoK (2021b). Range management and pastoralism strategy 2021–2031. Nairobi: Ministry of Agriculture. Livestock, Fisheries and Cooperatives.

42

GoK (2022a). Fourth Medium term plan 2023–2027. Nairobi: The National Treasury and Planning. State Department for Planning.

43

IGAD (2020a). IGAD Protocol on transhumance. Nairobi: ICPALD.

44

IGAD (2020b). Regional strategic framework: rangeland management for arid and semi-arid lands of the IGAD region. Nairobi: IGAD Centre for Pastoral Areas and Livestock Development (ICPALD) and the World Bank.

45

ILRI (2022). Index-based livestock insurance: reflecting on success. Available online at: https://www.ilri.org/news/index-based-livestock-insurance-reflecting-success.

46

Isiolo County Government (2018). County integrated development plan (CIDP) 2018-2022. Isiolo: Isiolo County Government.

47

JensenC.JohanssonS.LöfströmM. (2018). Policy implementation in the era of accelerating projectification: synthesizing Matland’s conflict–ambiguity model and research on temporary organizations. Public Policy Adm.33 (4), 447–465. 10.1177/0952076717702957

48

KALRO (2022). Livestock. From Kenya agricultural and livestock research organization. Available online at: https://www.poverty-action.org/organization/kenya-agricultural-and-livestock-research-organization-kalro.

49

KHRC (2018). Ethnicity and politicization in Kenya. Nairobi Kenya Hum. Rights Comm.

50

KIPPRA (2021). Public policy formulation process in Kenya. Repos. Available online at: https://kippra.or.ke/download/public-policy-formulation-in-kenya-1-pdf/.

51

KLRC (2015). “A Guide to the legislative process in Kenya,” in Nairobi: Kenya law Reform commission.

52

Mandera County Government (2018). County integrated development plan 2018–2022. Nairobi: County Government.

53

ManzanoP.BurgasD.CadahíaL.EronenJ. T.Fernández-LlamazaresÁ.BencherifS.et al (2021). Toward a holistic understanding of pastoralism. One Earth4 (5), 651–665. 10.1016/j.oneear.2021.04.012

54

Marsabit County Government (2018). County integrated development plan (CIDP) 2018-2022. Marsabit: Marsabit County Government.

55

Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Irrigation. (2019). National livestock policy 2019[Policy paper]. Retrieved from Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA) repository

56

NyarikiD. M.AmwataD. A. (2019). The value of pastoralism in Kenya: application of total economic value approach. Springer.

57

OdhiamboM. O. (2021). Priority areas for action and research on pastoralism and rangelands in eastern Africa. Int. Grassl. Congr. Proc. KALRO.

58

OECD (2009). “Evaluation of Norwegian development Co-operation in the fisheries sector,” in Norway: Norwegian agency for development cooperation.

59

OXFAM (2022nda). Gender equity analysis of the proposed own source revenue (OSR) policy and legislation in Kenya: case of Turkana and nairobi city counties. Publ. Available online at: https://kenya.oxfam.org/latest/policy-paper/gender-equity-analysis-proposed-own-source-revenue-osr-policy-and-legislation.

60

PacjaILRIKlmcCMRD (2022). Policy brief – economic benefits of pastoralism, centre for minority rights development (CEMIRIDE). Available online at: https://www.cemiride.org/policy-brief-economic-benefits-of-pastoralism/ (Accessed April 11, 2025).

61

RodgersC. (2021). Community engagement in pastoralist areas: lessons from the public dialogue process for a new refugee settlement in Turkana, Kenya. California: Springer.

62

ScoonesI. (2021). Pastoralists and peasants: Perspectives on agrarian change. J. Peasant Stud.48 (1), 1–47. 10.1080/03066150.2020.1802249

63

World Bank (2018). “Community engagement strategies,” in UNCTAD–World Bank knowledge into action series, note 15 (Washington, DC: World Bank).

Summary

Keywords

pastoralism, pastoralist, policy, rangelands, Kenya

Citation

Ndiritu SW, Waimiri AMG, Muthanga A and Baskaran-Makanju S (2025) An in-depth assessment of pastoral policy landscape in Kenya. Pastoralism 15:14334. doi: 10.3389/past.2025.14334

Received

13 January 2025

Accepted

03 June 2025

Published

10 July 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Edited by

Carol Kerven, University College London, United Kingdom

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Ndiritu, Waimiri, Muthanga and Baskaran-Makanju.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: S. Wagura Ndiritu, sndiritu@strathmore.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.