Abstract

Background:

Calcium and magnesium are essential ions that regulate multiple functions of keratinocytes. However, their precise effects on keratinocyte behavior remain incompletely understood.

Objectives:

To investigate the effects of varying calcium and magnesium concentrations on cell proliferation, migration, and the expression of genes related to differentiation and skin hydration in keratinocytes.

Methods:

HaCaT cells were stimulated by culture media with various calcium (0.32–18.0 mM) and magnesium concentrations (0.28–8.11 mM). MTT Assay was performed for proliferation. Cell migration ability was observed for 24 h using culture-Insert 2 well. mRNA levels of differentiation-associated gene expression was examined by qPCR assay.

Results:

Compared to standard DMEM, lower calcium concentrations and higher magnesium concentrations promoted keratinocyte proliferation. The combination of low calcium and high magnesium additively enhanced cell migration. However, both conditions tended to suppress the expression of genes related to differentiation and moisture retention.

Conclusion:

Keratinocyte functions related to proliferation, migration, and differentiation are intricately regulated by the concentrations of calcium and magnesium, as well as their interactions. Lower calcium and higher magnesium medium might have potential to enhance proliferation and migration in keratinocytes. However, further investigations under in vivo conditions are required to evaluate their effects and to translate these findings into clinical applications.

Introduction

The skin serves as a vital organ for maintaining physiological homeostasis and defending the body against external stressors. It comprises a variety of cell types, including keratinocytes, fibroblasts, neurons, and immune cells. Among these, keratinocytes fulfill multiple essential functions, such as forming the epidermal barrier to retain moisture and initiating re-epithelialization in response to tissue injury. These cellular processes are intricately regulated by intracellular signaling cascades and extracellular environmental factors, particularly the concentrations of calcium and magnesium [1–3]. In aging skin and inflamed skin, the calcium gradient in the epidermis is weakened or significantly disrupted. Adjusting the calcium-to-magnesium ratio to favor magnesium is beneficial for restoring epidermal homeostasis, leading to optimal repair of the skin barrier and potentially influencing inflammatory skin diseases [4].

Since Boukamp et al. established HaCaT cells in 1988 [5], this cell line has served as a representative in vitro model for human epidermal research. Numerous studies using this cell line have been conducted over many years, investigating the effects of minerals present in culture media on fundamental cellular functions such as proliferation, migration, and differentiation, as well as on more specific characteristics like differentiation profiles and calcium responsiveness [3, 6]. Several studies have reported that high concentrations of magnesium under in vitro conditions enhance the migratory capacities of keratinocytes [2, 3]. During wound healing process, the re-epithelialization process is achieved through the proliferation and migration of basal keratinocytes in the epidermis. Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated the promoting effect of magnesium and silver containing dressing in mouse skin wound healing model [7]. These findings suggest that external magnesium administration to the wound site may influence the keratinocytes, resulting in promoting wound healing.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by impaired skin barrier function, itching, and type 2 inflammation [8]. Filaggrin (FLG), a critical protein involved in epidermal differentiation, plays a fundamental role in preserving skin barrier integrity and maintaining hydration. It strengthens the structural stability of corneocytes and contributes to the generation of natural moisturizing factors (NMFs) [9]. In recent years, treatments involving mineral-rich natural extracts, such as hot spring and deep-sea water, have been reported to strengthen skin barrier integrity and reduce inflammation in conditions such as AD and psoriasis [10–12]. Interestingly, a recent study employing biotin permeability assays on lesional skin from patients with AD demonstrated that biotin can permeate down to the spinous layer, as a consequence of tight junction disruption [13]. We recently examined a recent phase II clinical trial which demonstrated a bath additive containing dissolved dolomite, that is a natural mineral source of calcium and magnesium, significantly improved both Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores and transepidermal water loss (TEWL) in patients with AD [14]. These findings indicate that calcium-and magnesium-containing water may have beneficial effects on skin health by modulating the physiology of the stratum corneum, granular layer, and spinous layer in inflammatory skin lesion.

Based on these findings, we aim to investigate future clinical applications of calcium-and magnesium-containing water. As a preliminary step, however, we deemed it essential to conduct a more detailed investigation into the effects of calcium and magnesium concentrations—and their ratio—on keratinocyte function under in vitro conditions. Indeed, several studies have demonstrated the individual effects of calcium and magnesium, as well as their ratios, on keratinocytes [1, 3, 6, 15]; however, detailed investigations into their comprehensive investigations into their combined effects remain limited. Therefore, we conducted this study using HaCaT cells to investigate the effects of different calcium-to-magnesium concentration ratios on keratinocyte functions, including proliferation, migration, and the expression of differentiation-related genes under in vitro condition.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human keratinocyte HaCaT cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Nissui Pharma, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA), 2 mmol/L l-glutamine (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd., Japan). Calcium -and magnesium-free DMEM was purchased from Cytiva (Tokyo, Japan). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Preparation of medium for cell stimulation

Since standard DMEM contains approximately 1.9 mM calcium and 1.6 mM magnesium [20], calcium- and magnesium-free DMEM was used to prepare the stimulation media. The media were supplemented with 1% FBS. Calcium chloride (CaCl2; WAKO) and magnesium sulfate (MgSO4; WAKO) were used to adjust the concentrations of calcium and magnesium, respectively. The calcium and magnesium concentrations were determined based on a previous study and the composition of standard DMEM medium [5, 16]. First, we gradually diluted the calcium and magnesium concentrations to establish the minimum concentration at which HaCaT cells could survive (Ca0.32-Mg0.28). The composition of the nine calcium- and magnesium-stimulating media used in the MTT assay is shown in Table 1. Specifically, Ca0.32-Mg0.28 contained 0.320 mM calcium; Ca0.90-Mg0.28 contained half the calcium concentration of standard DMEM; Ca9.01-Mg0.28 and Ca18.0-Mg0.28 contained fivefold and tenfold higher calcium concentrations, respectively. These conditions were applied following initial cell culture and seeding in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. For the magnesium-adjusted conditions (Ca0.32-Mg0.41, Ca0.32-Mg4.06, and Ca0.32-Mg8.11), the calcium concentration was fixed at 0.320 mM Ca0.32-Mg0.41 contained half the magnesium concentration of standard DMEM, while Ca0.32-Mg4.06 and Ca0.32-Mg8.11 contained fivefold and tenfold higher concentrations, respectively. Based on the MTT assay results from the media listed in Table 1, optimized calcium and magnesium concentrations were selected for further analysis, as shown in Table 2. These conditions were chosen based on their ability to most effectively enhance cell proliferation compared to standard DMEM, Ca0.32-Mg0.28, Ca0.90-Mg0.28, Ca9.01-Mg0.28, Ca18.0-Mg0.28, Ca0.32-Mg0.41, Ca0.32-Mg4.06, and Ca0.32–Mg8.11 conditions.

TABLE 1

| Medium name | Concentration conditions | Calcium [mM] | Magnesium [mM] |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMEM | Calcium 1-fold , magnesium 1-fold | 1.80 | 0.81 |

| Ca0.32-Mg0.28 | Calcium low, magnesium low | 0.32 | 0.28 |

| Ca0.90-Mg0.28 | Calcium 1/2-fold, magnesium low | 0.90 | 0.28 |

| Ca9.01-Mg0.28 | Calcium 5-fold, magnesium low | 9.01 | 0.28 |

| Ca18.0-Mg0.28 | Calcium 10-fold, magnesium low | 18.0 | 0.28 |

| Ca0.32-Mg0.41 | Calcium low, magnesium 1/2-fold | 0.32 | 0.41 |

| Ca0.32-Mg4.06 | Calcium low, magnesium 5-fold | 0.32 | 4.06 |

| Ca0.32-Mg8.11 | Calcium low, magnesium 10-fold | 0.32 | 8.11 |

Concentration profiles of stimulation media.

TABLE 2

| Medium name | Concentration conditions | Calcium [mM] | Magnesium [mM] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ca0.32-Mg0.28 | Calcium low, magnesium low | 0.32 | 0.28 |

| Ca0.90-Mg0.28 | Calcium 1/2-fold, magnesium low | 0.9 | 0.28 |

| Ca0.32-Mg8.11 | Calcium low, magnesium 10-fold | 0.32 | 8.11 |

| Ca0.90-Mg8.11 | Calcium 1/2-fold, magnesium 10-fold | 0.9 | 8.11 |

Combination conditions of calcium and magnesium.

MTT assay

HaCaT cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5,000 cells per well in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the medium was replaced with one of the stimulation media listed in Table 1 or Table 2. Cells were then incubated for 48 h. AQueous One Solution Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added and incubated for 2 h. The absorbance at 490 nm was measured using an ELISA plate reader, following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cell migration assay

HaCaT cells were seeded into the two chambers of a Culture-Insert 2 Well placed in a µ-Dish 35 mm (Ibidi, Gräfelfing, Germany) at a density of 8.25 × 104 cells per chamber in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the medium was replaced with the test media listed in Table 2, each containing 10 μg/mL Mitomycin C (Gibco), to inhibit cell proliferation and assess migratory capacity alone. Following an additional 1-hour incubation, the culture inserts were removed to create a defined cell-free gap. The medium was replaced again with the corresponding test medium, and phase-contrast images were captured at 0 and 24 h using a digital inverted microscope. The area of the cell-free region was quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, version 1.54).

qPCR

HaCaT cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 6.0 × 105 cells per well using DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the culture medium was replaced with the stimulation media described in Table 2. Following 72 h of stimulation, total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Netherlands), and RNA concentration was measured with a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from the isolated RNA using the GoScript™ Reverse Transcription System (Promega, USA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR Green system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on an ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Primer sequences used in this study are listed in Table 3. Gene expression levels were normalized to 18S rRNA, and relative expression was calculated using the 2^−ΔΔCt method.

TABLE 3

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| 18S | Forward: GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT |

| Reverse: CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG | |

| FLG | Forward: TGTGAGAGACAGTGGAGCGA |

| Reverse: GATGAGGCTGGTCTTGTTGG | |

| TG-1 | Forward: GAGAGTGGCAGATGAGGAGG |

| Reverse: TCAGGTGGTGTGGTTGTAGC | |

| IVL | Forward: CTCTGCGCTCTTCAACCTCT |

| Reverse: TGGTGTAGTGGCTGGTTTGT | |

| ZO-1 | Forward: GAGGAGCAGCAGTTGAGTGA |

| Reverse: ACATGAGGAGGGACACTTGG | |

| CERS3 | Forward: ACCAAGCCAGGTGTTTATGG |

| Reverse: CTTCCTTCCACAGAGGTTGC | |

| CERS4 | Forward: GCATGTTGGTGTTCCTGTTG |

| Reverse: GCTGTGGAGGATGATGGTTC | |

| SPTLC2 | Forward: AGGTTGGTGGAGCTGTTTGA |

| Reverse: GAGACACCTGTCTGGCTGAG | |

| GBA | Forward: AGACACCATCGAGGAGTTGC |

| Reverse: CAGCAGGTTGTCAGGTTGTT | |

| SMPD1 | Forward: TGCAGAGGAGTGGACTTTGA |

| Reverse: TGAGATGAGGAGGAGGAGGA | |

| SGMS1 | Forward: ACCAAGGAGGACAAAGAGCA |

| Reverse: TGGTGATGGAGTAGGAGGGA | |

| SGMS2 | Forward: ATGTCCTGGTGTTTGGCTTT |

| Reverse: CAGGAGGGATCTTCTTGGGT | |

| ELOVL1 | Forward: CTCTGCTGAGGATGGTGTGA |

| Reverse: TCCAGTTTCCACAGCACTTT | |

| ELOVL4 | Forward: GGAGGAGGAAGGAGGAAAGG |

| Reverse: TGGTGCTGTAGTCCTGCTTC |

Primer information of qPCR.

Statistics

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE) or ±standard deviation. Statistical comparisons among multiple groups were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

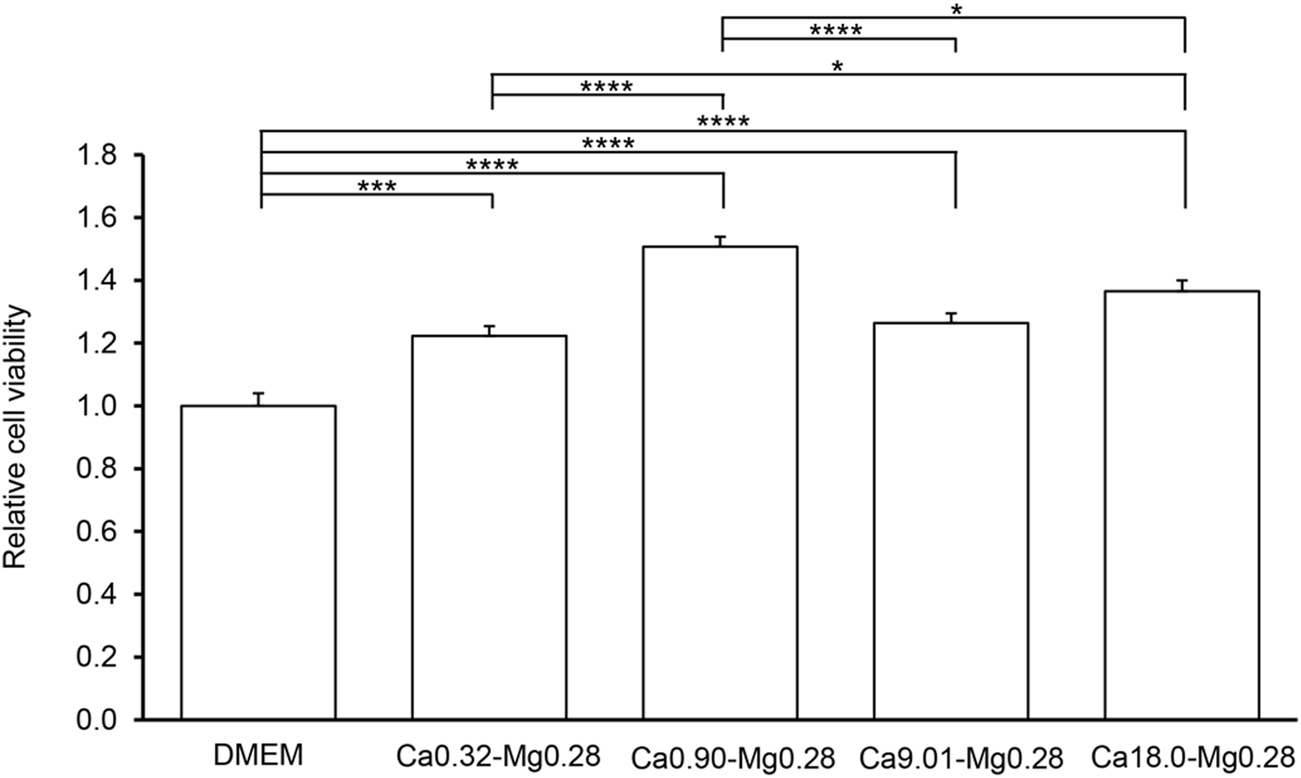

Cell proliferation capacity at different calcium concentrations in keratinocytes

First, we assessed the effect of varying calcium concentrations on keratinocyte proliferation. Standard DMEM served as the control, and media with different calcium concentrations (Ca0.32-Mg0.28, Ca0.90-Mg0.28, Ca9.01-Mg0.28, and Ca18.0-Mg0.28) under low magnesium conditions were tested, as shown in Table 1. The MTT assay results demonstrated that all low-calcium conditions (Ca0.32-Mg0.28, Ca0.90-Mg0.28, Ca9.01-Mg0.28, and Ca18.0-Mg0.28) significantly enhanced cell proliferation compared to the DMEM control (Figure 1). The greatest proliferative activity was observed in Ca0.90-Mg0.28, which contained approximately half the calcium concentration of standard DMEM and resulted in a 1.5-fold increase in proliferation. In contrast, Ca9.01-Mg0.28 and Ca18.0-Mg0.28 showed no further enhancement, with proliferation levels remaining nearly unchanged.

FIGURE 1

Cell proliferation capacity at different calcium concentrations in keratinocytes. MTT assay using HaCaT cells. The vertical axis represents the relative absorbance, with DMEM set to 1. The horizontal axis indicates each experimental medium. Data are presented as the mean +SEM (n = 10). Statistical significance is indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.0001.

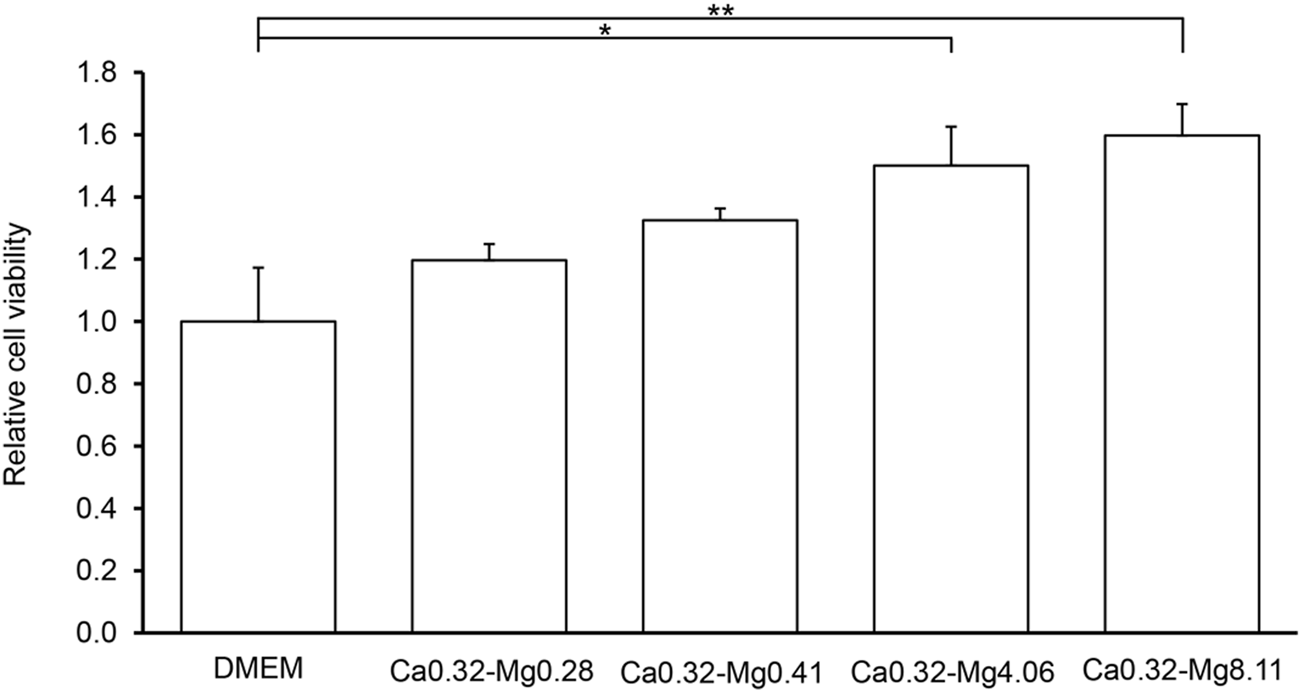

Cell proliferation capacity at different magnesium concentrations in keratinocytes

Next, we examined how varying magnesium concentrations influence keratinocyte proliferation. Standard DMEM served as the control, and media with different magnesium concentrations (Ca0.32-Mg0.28, Ca0.32-Mg0.41, Ca0.32-Mg4.06, and Ca0.32-Mg8.11) under low calcium conditions were tested (Table 1). The MTT assay results revealed that cell proliferation increased in a concentration-dependent manner. The highest proliferation was observed in Ca0.32-Mg8.11, which contained a magnesium concentration 10 times higher than that of standard DMEM (Figure 2). Under this condition, proliferation was approximately 2.3 times greater than that of DMEM control.

FIGURE 2

Cell proliferation capacity at different magnesium concentrations in keratinocytes. MTT assay using HaCaT cells. The vertical axis represents relative absorbance, with DMEM set to 1, and the horizontal axis represents each medium. All values are expressed as the mean +SEM (n = 10). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

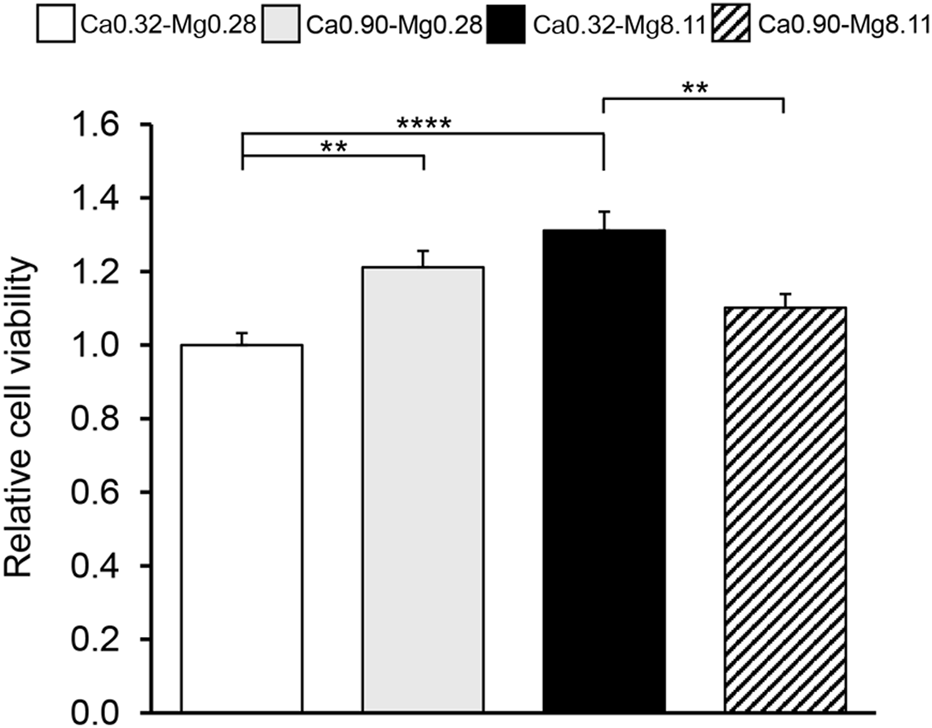

Cell proliferation capacity at different calcium and magnesium concentrations in keratinocytes

We next examined the combined effects of calcium and magnesium concentrations on keratinocyte proliferation. The low-calcium, low-magnesium condition (Ca0.32-Mg0.28) served as the control, and the most effective concentrations identified in the individual calcium- and magnesium-only experiments (Figures 1, 2; Table 2) were applied. MTT assay results revealed that both Ca0.90-Mg0.28 and Ca18.0-Mg0.28 significantly enhanced cell proliferation compared to the Ca0.32-Mg0.28 control (Figure 3). However, proliferation under the Ca0.32-Mg8.11 condition was unexpectedly lower than that observed in the varying magnesium concentrations group.

FIGURE 3

Cell proliferation capacity at different calcium and magnesium concentrations in keratinocytes. MTT assay using HaCaT cells. The vertical axis represents relative absorbance, with Ca0.32-Mg0.28 set to 1, and the horizontal axis indicates each medium. All values are expressed as the mean +SEM (n = 10). **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.001.

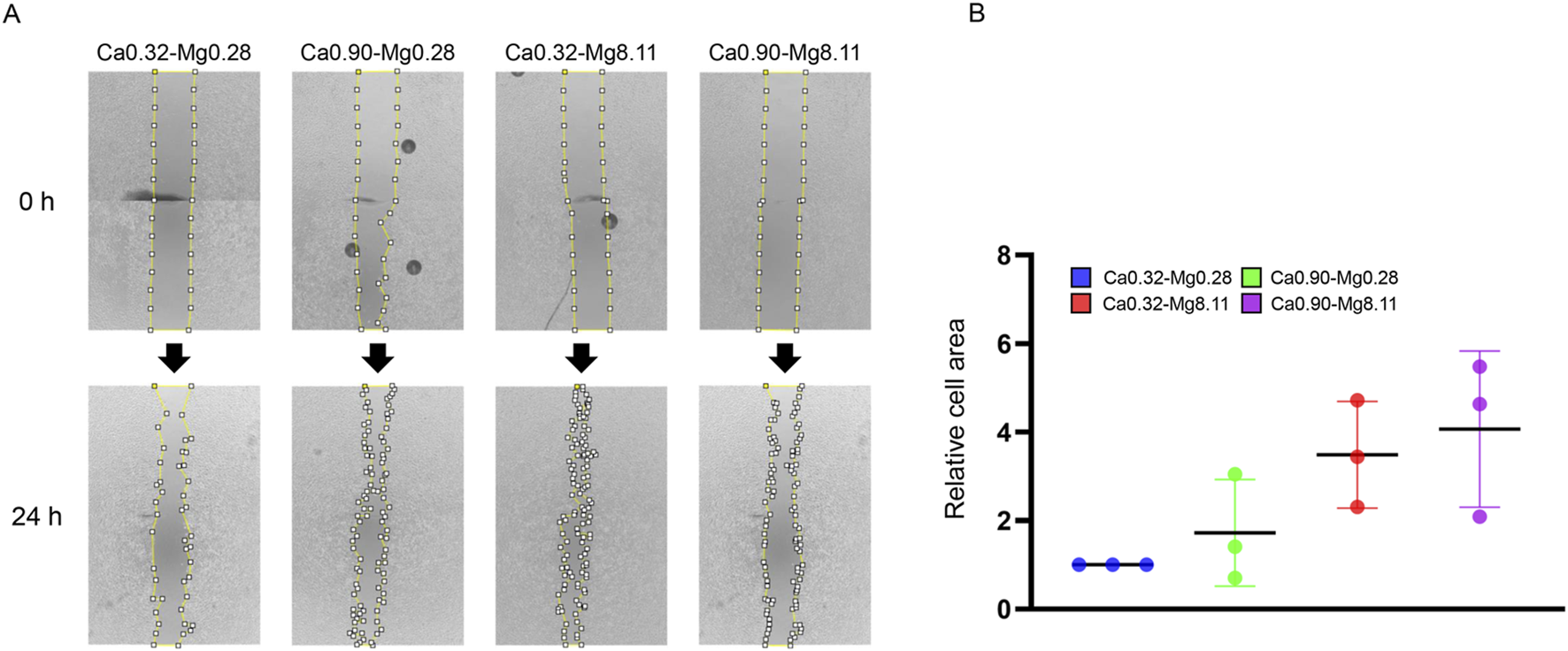

Cell migration capacity at different calcium and magnesium concentrations

We next investigated the combined effects of calcium and magnesium concentrations on keratinocyte migration. Stimulation with medium containing different concentration of calcium and magnesium resulted in an approximately 1.4-fold increase in migration under the Ca0.90-Mg0.28 condition, 3.13-fold increase in Ca0.32-Mg8.11, and 3.46-fold increase in Ca0.90-Mg8.11, respectively, compared to the control condition (Ca0.32-Mg0.28). These findings suggest that 0.9 mM calcium induces a modest enhancement of migratory capacity, whereas 8.11 mM magnesium promotes migration more robustly. Furthermore, an additive effect of calcium and magnesium on the enhancement of migratory capacity was also observed (Figures 4A,B).

FIGURE 4

Cell migration capacity at different calcium and magnesium concentrations. (A) The upper panel displays images captured immediately after calcium and magnesium stimulation (0 h), while the lower panel shows images taken after 24 h of incubation. (B) Quantitative analysis of the wound area was performed using ImageJ software. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

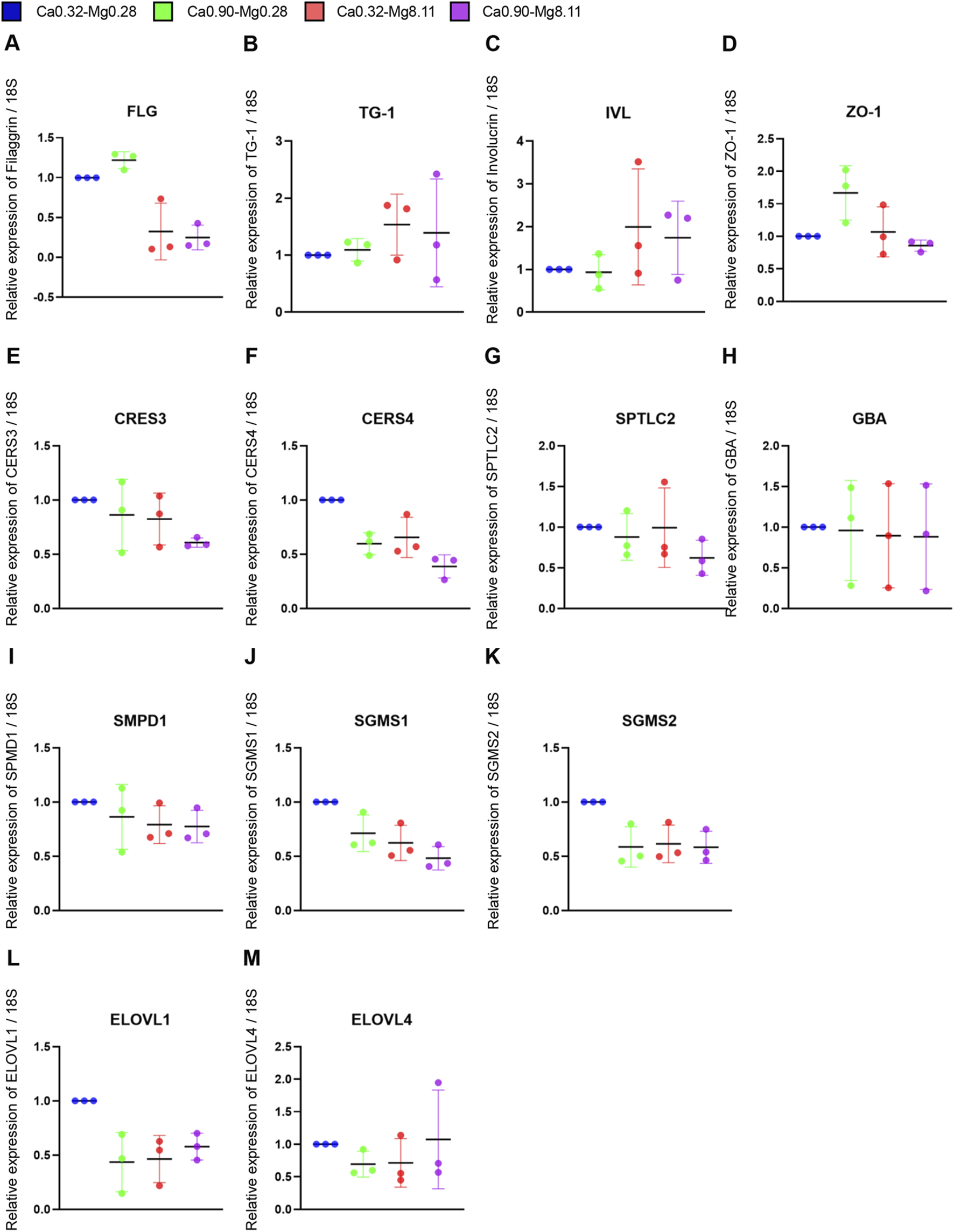

Effect of different calcium and magnesium concentrations on keratinocyte differentiation

Finally, we examined the effect of varying calcium and magnesium concentration on keratinocytes differentiation. Cells were stimulated with the media compositions listed in Table 2. Quantitative PCR analysis showed that FLG mRNA expression was increased by approximately 1.2-fold under the Ca0.90-Mg0.28 condition but was markedly reduced to approximately 0.3-fold and 0.2-fold under high-magnesium conditions (Ca0.32-Mg8.11 and Ca0.90-Mg8.11, respectively) (Figure 5A). Calcium stimulation with Ca0.90-Mg0.28 did not alter the mRNA expression levels of transglutaminase 1 (TG1) and involucrin (IVL) compared to the control. However, TG1 expression was increased by approximately 1.5-fold, and IVL by 1.8-fold, in the high-magnesium conditions (Ca0.32-Mg8.11. and Ca0.90-Mg8.11) (Figures 5B,C). Stimulation with Ca0.90-Mg0.28 increased ZO-1 mRNA expression by approximately 1.7-fold relative to the control, while Ca0.90-Mg0.28 had no effect. Interestingly, the upregulation of ZO-1 induced by Ca0.90-Mg0.28 was abolished in the Ca0.90-Mg8.11 condition (Figure 5D).

FIGURE 5

qPCR results for expression of differentiation-related genes. Quantitative PCR analysis was performed to evaluate the mRNA expression levels of the following genes: FLG(A), TG-1(B), IVL(C), ZO-1(D), CERS3(E), CERS4(F), SPTLC2(G), GBA(H), SMPD1(I), SGMS1(J), SGMS2(K), ELOVL1(L), and ELOVL4(M). The vertical axis represents the relative expression level normalized to Ca0.32-Mg0.28 (set to 1), and the horizontal axis shows the different culture media. All data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

We next evaluated the mRNA expression of genes related to ceramide synthesis.

CERS3 and CERS4 expression levels were reduced to approximately 0.8-fold and 0.6-fold, respectively, in both Ca0.90-Mg0.28 and Ca0.32-Mg8.11 conditions compared to the control, with a further reduction observed in the Ca0.90-Mg8.11 group (Figures 5E,F). Expression of SPTLC2 remained unchanged under Ca0.90-Mg0.28 and Ca0.32-Mg8.11 conditions but was downregulated to approximately 0.6-fold in the Ca0.90-Mg8.11 condition (Figure 5G). GBA expression remained unchanged across all conditions (Figure 5H). Among the sphingomyelin-related genes, SMPD1 expression was reduced to about 0.8-fold in high-magnesium conditions (Ca0.32-Mg8.11 and Ca0.90-Mg8.11) compared to the control (Figure 5I). SGMS1 expression decreased to approximately 0.7-fold under Ca0.90-Mg0.28 and decreased to approximately 0.6-fold under Ca0.32-Mg8.11. An additive inhibitory effect was observed in the Ca0.90-Mg8.11 condition (Figure 5J). SGMS2 expression was reduced to approximately 0.6-fold under all experimental conditions (Figure 5K). Regarding fatty acid elongation-related genes, ELOVL1 expression was decreased approximately 0.5-fold in all tested conditions (Figure 5L). ELOVL4 expression was reduced to approximately 0.8-fold in both Ca0.90-Mg0.28 and Ca0.32-Mg8.11, while no marked change was seen under the Ca0.90-Mg8.11 condition (Figure 5M).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated how varying concentrations of calcium and magnesium influence epidermal cell functions, including proliferation, migration, and differentiation.

Calcium is the most extensively studied factor regulating both proliferation and differentiation in keratinocytes. However, most previous studies have focused exclusively on calcium, often overlooking the potential role of magnesium. For instance, one study compared keratinocyte proliferation under low (0.09 mM) and high (1.2 mM) calcium conditions and found no significant difference; however, it did not consider the influence of magnesium [6]. In contrast, other studies have reported that keratinocyte proliferation is enhanced under conditions of either reduced calcium or elevated magnesium concentrations compared to those in standard DMEM [3, 17]. One notable finding of our study is that the combination of low calcium and magnesium (Ca0.32-Mg0.28) significantly increased cell proliferation compared to standard DMEM. Although DMEM is widely used for culturing various cell types, including HaCaT cells, due to its versatility, our results suggest that it may not offer optimal conditions for promoting keratinocyte proliferation. We observed the highest proliferative capacity under low-magnesium conditions combined with approximately half the calcium concentration of standard DMEM (Ca0.9-Mg0.28). Previous study reported that high magnesium concentrations (5.8 mM) did not change cell proliferation with no change of cyclin D1 (CCND1) mRNA levels after stimulation [2]. However, we newly found that under low-calcium conditions, proliferation increased in a magnesium concentration-dependent manner, peaking at 10 times the magnesium concentration found in standard DMEM (Ca0.32-Mg8.11).

We next evaluated whether the combination of calcium and magnesium exerted an additive effect on cell proliferation. As a novel observation in our study, increasing the calcium concentration appeared to counteract the proliferative enhancement induced by high magnesium stimulation. It is well known that magnesium regulates several other cations, including sodium, potassium, and calcium, and that high extracellular magnesium concentrations can inhibit calcium influx into cells [18]. This magnesium’s role as an antagonist to calcium is recognized as a fundamental biological principle observed in various tissues such as the brain, muscles, and kidneys [19]. However, whether high calcium levels suppress intracellular magnesium influx remains unclear and further investigation is required to clarify this mechanism.

Previous studies have demonstrated that cell motility increases in a concentration-dependent manner, peaking at approximately 1.1 mM calcium and 3.3 mM magnesium. They also suggested that enhanced migratory capacity is mediated through a competitive interplay between calcium-dependent E-cadherin-mediated adhesion and magnesium-dependent α2β1-integrin-mediated adhesion [3, 15]. In line with these findings, the present study showed that a combination of calcium and magnesium exerted a partial additive effect on cell migration. Interestingly, this additive effect in cell migration appeared to have the opposite outcome in terms of cell proliferation, as described above. This novel finding suggest that the combined presence of calcium and magnesium ions exerts different effects depending on cellular function.

Our findings also provide a new context for the “calcium switch”, the well-established concept that high extracellular calcium induces keratinocyte differentiation [1]. In differentiation assays using HaCaT cells, experimental conditions typically include calcium concentrations exceeding 1 mM, high cell density, and extended culture duration [20]. In our experiment, both cell density and culture duration were considered appropriate for promoting differentiation. However, the calcium concentration used in Ca0.90-Mg0.28 and Ca0.90-Mg8.11 media (Ca 0.9 mM) may have been slightly below the threshold required for full induction of differentiation, potentially making the difference from the low-calcium condition in Ca0.32-Mg0.28 (Ca 0.32 mM) less distinct. Furthermore, an extremely high extracellular magnesium concentration exerted a strong suppressive effect, sufficient to counteract the modest differentiation-promoting effect of calcium, as evidenced by qPCR results for FLG and ZO-1 expression. These results showed that calcium concentration alone does not absolutely control the keratinocytes differentiation; rather, it is substantially modulated by extracellular magnesium concentrations, consistent with previous reports indicating that magnesium concentrations exceeding those in standard DMEM can inhibit filaggrin synthesis [2]. TG-1, an enzyme involved in cornified envelope formation, and IVL, its precursor protein, are both well-established markers of terminal keratinocyte differentiation. A prior study reported that high magnesium concentrations (5.8 mM) in DMEM reduced differentiation in HaCaT cells [2]. Interestingly, our study found a slight increase in TG-1 and IVL expression under high-magnesium conditions (Ca0.32-Mg8.11 and Ca0.90-Mg8.11). Although the precise reason for this discrepancy is unclear, it may be attributed to the higher magnesium concentration and relatively longer culture period used in our study. Nonetheless, as our results are based solely on mRNA expression, further validation at the protein level is warranted.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the expression of genes involved in ceramide synthesis (CERS4, GBA) and sphingomyelin metabolism (SMPD1, SGMS1) is upregulated under calcium concentrations ranging from 1.1 to 1.8 mM in standard magnesium conditions [21–24]. However, the influence of magnesium concentration on the expression of these genes has not been previously addressed. A key novel finding of our study is that the mRNA expression levels of ceramide synthesis–related genes (CERS3, CERS4, SPTLC2), with the exception of GBA, and sphingomyelin-related genes (SMPD1, SGMS1) were markedly reduced under the calcium and magnesium conditions that most strongly promoted keratinocyte migration. These findings suggest that ion conditions that enhance cell motility may simultaneously suppress the expression of genes critical for skin barrier function and moisture retention. ELOVL1 is highly expressed in the skin and plays a central role in maintaining the skin barrier by contributing to the biosynthesis of ceramides and other long-chain lipids necessary for hydration, protection, and structural integrity [25]. Despite its importance, the effects of calcium and magnesium concentrations on the expression of the ELOVL gene family have not been thoroughly investigated. Our results showed that ELOVL1 and ELOVL4 mRNA levels were decreased under Ca0.90-Mg0.28 and Ca0.32-Mg8.11 conditions, and this suppression was partially alleviated in the Ca0.90-Mg8.11 condition. These observations raise the possibility that calcium–magnesium interactions may modulate ELOVL gene expression. However, given that only two concentrations of calcium and magnesium were tested in this study, more comprehensive investigations are needed to elucidate the underlying regulatory mechanisms.

This study has several limitations. First, the experiments were conducted using HaCaT cells, an immortalized human keratinocyte cell line, without validation in normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs) or primary mouse keratinocytes. Second, all experiments were performed in vitro, and the findings may not fully reflect in vivo physiological conditions. According to previous reports, the concentrations of calcium and magnesium in the extracellular fluid immediately after ulcer induction in rats and pigs were 1.52 mM and 1.43 mM, respectively [15]. In addition, it has been reported that wound dressings containing magnesium and silver can create a localized environment with a high magnesium concentration of approximately 2.2 mM [7]. The calcium concentrations used in our study (0.32–0.9 mM) were slightly lower than physiological levels, whereas the magnesium concentration of 8.11 mM represents a substantially elevated level compared to normal conditions. Further investigation is needed to clarify the effects of this concentration under physiological conditions. In addition, under the current differentiation experiment conditions, calcium and magnesium were applied at concentrations corresponding to those experienced by undifferentiated basal keratinocytes, which do not yet undergo terminal differentiation in vivo. Even in pathological conditions such as atopic dermatitis, where tight junctions are disrupted, the effects of externally applied calcium and magnesium solutions are likely limited to the spinous layer. Therefore, further investigation under differentiated conditions is required to fully evaluate the impact of calcium and magnesium. Third, the calcium and magnesium concentrations used in this study were selected based on their effects on cell proliferation and migration. As a result, they may not be optimal for evaluating barrier-related functions such as keratinocyte differentiation. Future studies are warranted to identify more appropriate ion concentrations to better assess the interaction between calcium and magnesium in the context of epidermal barrier function. Lastly, in some of the experiments, the sample size was too small to allow for appropriate statistical analysis. Therefore, we have limited our presentation to observed trends based on raw values.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that keratinocyte functions related to proliferation, migration, and differentiation are intricately regulated by the concentrations of calcium and magnesium, as well as their interactions. Culture media with lower calcium and higher magnesium concentration may have the potential to enhance proliferation and migration in keratinocytes. However, further investigations under in vivo conditions are required to evaluate their effects and to facilitate the translation of these findings into clinical applications.

Statements

Data availability statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in Figshare (Accession number: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30656543.v1).

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

Author contributions

KH and AU conducted the experiments, KH, MH, HI, AU and SI-M wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. GUDi Co. Ltd., and donation from Graduate School of Science and Technology, Gunma University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. We used ChatGPT5 for grammar correction.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Abbreviations

AD, Atopic dermatitis; DMEM, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium; FBS, Fetal bovine serum, FLG, Filaggrin; IVL, Involucrin; TG-1, Transglutaminase 1; ZO-1, Zonula occludens-1; CERS, Ceramide synthase; SPTLC, Serine palmitoyltransferase long chain base subunit; GBA, Glucosylceramidase beta; SMPD, Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase; SGMS, Sphingomyelin synthase; ELOVL, Elongation of very long chain fatty acids protein; TEWL, Transepidermal water loss; qPCR, Quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

References

1.

BikleDDXieZTuCL. Calcium regulation of keratinocyte differentiation. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab (2012) 7(4):461–72. 10.1586/eem.12.34

2.

YoshinoYTeruyaTMiyamotoCHiroseMEndoSIkariA. Unraveling the mechanisms involved in the beneficial effects of magnesium treatment on skin wound healing. Int J Mol Sci (2024) 25(9):4994. 10.3390/ijms25094994

3.

GrzesiakJJPierschbacherMD. Changes in the concentrations of extracellular Mg++ and Ca++ down-regulate E-cadherin and up-regulate alpha 2 beta 1 integrin function, activating keratinocyte migration on type I collagen. J Invest Dermatol (1995) 104(5):768–74. 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12606983

4.

HaftekMAbdayemRGuyonnet-DebersacP. Skin minerals: key roles of inorganic elements in skin physiological functions. Int J Mol Sci (2022) 23(11):6267. 10.3390/ijms23116267

5.

BoukampPPetrussevskaRTBreitkreutzDHornungJMarkhamAFusenigNE. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J Cell Biol (1988) 106(3):761–71. 10.1083/jcb.106.3.761

6.

MicallefLBelaubreFPinonAJayat-VignolesCDelageCCharveronMet alEffects of extracellular calcium on the growth-differentiation switch in immortalized keratinocyte HaCaT cells compared with normal human keratinocytes. Exp Dermatol (2009) 18(2):143–51. 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00775.x

7.

PanSCHuangYJWangCHHsuCKYehML. Novel Magnesium- and silver-loaded dressing promotes tissue regeneration in cutaneous wounds. Int J Mol Sci (2024) 25(17):9311. 10.3390/ijms25179311

8.

SaekiHOhyaYArakawaHIchiyamaSKatsunumaTKatohNet alExecutive summary: japanese guidelines for atopic dermatitis (ADGL) 2024. Allergol Int (2025) 74(2):210–21. 10.1016/j.alit.2025.01.003

9.

SandilandsASutherlandCIrvineADMcLeanWH. Filaggrin in the frontline: role in skin barrier function and disease. J Cell Sci (2009) 122(Pt 9):1285–94. 10.1242/jcs.033969

10.

BakJPKimYMSonJKimCJKimEH. Application of concentrated deep sea water inhibits the development of atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in NC/Nga mice. BMC Complement Altern Med (2012) 12:108. 10.1186/1472-6882-12-108

11.

EmmanuelTPetersenAHouborgHIRønsholdtABLybaekDSteinicheTet alClimatotherapy at the dead sea for psoriasis is a highly effective anti-inflammatory treatment in the short term: an immunohistochemical study. Exp Dermatol (2022) 31(8):1136–44. 10.1111/exd.14549

12.

ProkschENissenHPBremgartnerMUrquhartC. Bathing in a magnesium-rich dead sea salt solution improves skin barrier function, enhances skin hydration, and reduces inflammation in atopic dry skin. Int J Dermatol (2005) 44(2):151–7. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02079.x

13.

BergmannSvon BuenauBVidalYSSHaftekMWladykowskiEHoudekPet alClaudin-1 decrease impacts epidermal barrier function in atopic dermatitis lesions dose-dependently. Sci Rep (2020) 10(1):2024. 10.1038/s41598-020-58718-9

14.

UchiyamaAInoueYUchidaKHiyamaMItabashiHMotegiSI. The effect of balneotherapy with natural mineral dissolved water on dry skin in atopic dermatitis: a phase IIa, nonrandomized, controlled study. J Cutan Immunol Allergy (2021) 4(6):159–65. 10.1002/cia2.12195

15.

GrzesiakJJPierschbacherMD. Shifts in the concentrations of magnesium and calcium in early porcine and rat wound fluids activate the cell migratory response. J Clin Invest (1995) 95(1):227–33. 10.1172/JCI117644

16.

LiangCCParkAYGuanJL. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc (2007) 2(2):329–33. 10.1038/nprot.2007.30

17.

TuCLCelliAMauroTChangW. Calcium-sensing receptor regulates epidermal intracellular Ca(2+) signaling and Re-Epithelialization after wounding. J Invest Dermatol (2019) 139(4):919–29. 10.1016/j.jid.2018.09.033

18.

Aparna Ann MathewRPPanonnummalR. Magnesium’-the master cation-as a drug—possibilities and evidences. Biometals (2021) 34(5):955–86. 10.1007/s10534-021-00328-7

19.

BaaijJHFHoenderopJGJBindelsRJM. Magnesium in man: implications for health and disease. Physiol Rev (2015) 95(1):1–46. 10.1152/physrev.00012.2014

20.

MicallefLBattuSPinonACook-MoreauJCardotPJDelageCet alSedimentation field-flow fractionation separation of proliferative and differentiated subpopulations during Ca2+-induced differentiation in HaCaT cells. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci (2010) 878(15-16):1051–8. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.03.009

21.

BrauweilerAMBinLKimBEOyoshiMKGehaRSGolevaEet alFilaggrin-dependent secretion of sphingomyelinase protects against staphylococcal α-toxin-induced keratinocyte death. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2013) 131(2):421–7.e72. 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.030

22.

LeeAY. Molecular mechanism of epidermal barrier dysfunction as primary abnormalities. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(4):1194. 10.3390/ijms21041194

23.

MizutaniYSunHOhnoYSassaTWakashimaTObaraMet alCooperative synthesis of ultra long-chain fatty acid and ceramide during keratinocyte differentiation. PLoS One (2013) 8(6):e67317. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067317

24.

ZunigaKGhousifamNSansaloneJSenecalKVan DykeMRylanderMN. Keratin promotes differentiation of keratinocytes seeded on collagen/keratin hydrogels. Bioengineering (Basel) (2022) 9(10):559. 10.3390/bioengineering9100559

25.

SassaTOhnoYSuzukiSNomuraTNishiokaCKashiwagiTet alImpaired epidermal permeability barrier in mice lacking elovl1, the gene responsible for very-long-chain fatty acid production. Mol Cell Biol (2013) 33(14):2787–96. 10.1128/MCB.00192-13

Summary

Keywords

calcium, magnesium, keratinocyte, proliferation, migration

Citation

Hirakata K, Hiyama M, Itabashi H, Uchiyama A and Motegi S-I (2025) Modulation of keratinocyte proliferation, migration, and differentiation by calcium and magnesium. J. Cutan. Immunol. Allergy 8:15491. doi: 10.3389/jcia.2025.15491

Received

27 August 2025

Revised

21 November 2025

Accepted

26 November 2025

Published

09 December 2025

Volume

8 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Hirakata, Hiyama, Itabashi, Uchiyama and Motegi.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kazushi Hirakata, t212c601@gunma-u.ac.jp; Akihiko Uchiyama, akihiko1016@gunma-u.ac.jp

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.