Abstract

Critical transitions in ecosystems occur when a “tipping point” is crossed, resulting in an abrupt shift to a new stable state that is almost impossible, to reverse. These changes produce severe socio-economic consequences, often displaying typical characteristics of tipping points at various societal levels, particularly in positive feedbacks, non-linearity, and irreversibility. These societal phenomena are analogously referred to as “negative social tipping points.” However, empirical studies examining the real-world dynamics of these social tipping points remain limited in scope, leaving unanswered questions about their significance in different contexts, the underlying causes and processes, and potentials for preventative human actions. This paper explores what such a social tipping point might be like within a specific social-ecological system: Namibian dryland pastoralism. Adopting a qualitative, ethnographic approach, this paper focuses on pastoralists who lost all their livestock. It investigates region-specific social and ecological factors that lead to such hardship, portraying people’s experiences throughout this process. This includes their views on what it means to ‘lose everything’ and their endeavours to restart livestock farming. It considers how to prevent other households in the region from facing similar challenges, and examines how pastoral lifestyles can be maintained in the face of ongoing rangeland degradation and climate change effects in the Anthropocene. Based on this analysis, the paper considers whether these social dynamics can be classified as social tipping points and, further, evaluates the usefulness of this classification in describing the observed phenomena.

Introduction

The present geological epoch is defined by significant and widespread impacts of human actions on Earth, resulting in the suggested term “Anthropocene” (Crutzen and Stoermer, 2000; Zalasiewicz et al., 2011; Lewis and Maslin, 2015). While responsibilities and vulnerabilities linked to these changes vary among individuals, groups, and societies (Sayre, 2012; Mathews, 2020), such impacts have caused notable changes in global temperatures, landscapes, and biodiversity (Crutzen, 2006; Steffen et al., 2015). Over the past two decades, scientists have warned that these processes may involve critical transitions in numerous complex environmental systems, including regional ecosystems (e.g., fisheries, rangelands) and entire biospheres (e.g., Antarctic ice sheet, or Amazon rainforest) (Steffen et al., 2018; Spake et al., 2022). Theoretically, these transitions involve crossing a “tipping point” (TP), implying an abrupt change that is self-perpetuating until a new stable state is reached (Lenton, 2013; Dakos et al., 2019). TPs are challenging to identify and predict, and difficult or impossible to reverse once crossed (Lenton, 2011; Dakos et al., 2024). Notable examples include disappearance of mountain glaciers (Xiao et al., 2023), vegetation collapse leading to desertification in drylands (Bestelmeyer et al., 2015), and transition of Amazon rainforest into white sand savannah (Flores et al., 2024).

Due to intrinsic linkages between environmental and social dynamic systems, ecological TPs are likely to have adverse, if not catastrophic, socioeconomic consequences if preventive measures, such as behavioral changes in environmental use and management, are not taken in time (Keys et al., 2019; Dietz et al., 2021). Accordingly, these undesirable impacts may exhibit typical TP characteristics at different social scales (e.g., individuals, households, communities, entire societies), particularly in terms of non-linearity and irreversibility, analogously referred to as “negative social TPs” (Kopp et al., 2016; van Ginkel et al., 2020; Spaiser et al., 2024). These are normatively distinguished from “positive social TPs,” which imply desirable changes in human actions toward sustainability and the prevention of systemic collapse, thereby supporting social systems and ecologies (David Tàbara et al., 2018; Winkelmann et al., 2022; Lenton et al., 2023). In the former case, social systems theoretically undergo an undesired, critical, and nearly irreversible transition between states, driven by self-reinforcing positive feedback mechanisms (Milkoreit et al., 2018; Lenton et al., 2023).

In conjunction with these conceptual developments, the number of publications utilising the social TP concept has increased exponentially in recent years (Milkoreit et al., 2018; Szabó et al., 2023). Initially, social scientists introduced this term to examine the dynamics of neighbourhood segregation (Grodzins, 1957; Schelling, 1971) and emergence of collective action processes (Granovetter, 1978). The concept has been applied in other contexts too, such as analyses of shifts in political systems (Nathan, 2013) and changes in economic conditions (Mukherji, 2013). However, scholars of human-environment relations have called for better focused application of the social TP concept to explore critical transitions in social systems intimately linked to ecological processes and transformations. Otherwise, they argue, vague application of the term can undermine the rigor and quality of analyses of social-ecological interactions and their outcomes (Milkoreit et al., 2018; Milkoreit, 2023).

Despite this context, there remains a lack of empirical case studies that explore the real-world dynamics of social tipping dynamics within social-ecological systems (Hodbod et al., 2024). Although some studies have sought to clarify the mechanisms behind historical societal collapses and transformations through the lens of tipping points (Fernández-Giménez et al., 2017; Lenton, 2023), these investigations primarily rely on secondary data and adopt an environmentally deterministic approach. As a result, such research exhibits some critical limitations, first identified by Anthropologist, Nuttall (2012), which still prevail. These limitations include: i) tendency to overlook the influence of socioeconomic, political, and cultural factors in shaping social-ecological dynamics and outcomes; and ii) disregard for the subjective nature of what constitutes a social TP for people in different contexts.

This paper aims to address such limitations by contributing to the ongoing discussion on social TP, using empirical research to examine how this phenomenon manifests within a specific social-ecological system–namely, a dryland pastoral system in Namibia. Guided by the principle for social TP analysis proposed by Hodbod et al. (2024), which suggests that case studies should be chosen according to their potential to exemplify social TP, this study focuses on a social issue in a setting likely to demonstrate this phenomenon: loss of livestock among pastoralists. This approach was supported by the understanding that social and ecological factors frequently impact this process, leading to significant changes in pastoralists’ livelihoods and posing notable challenges for those attempting to revert to livestock rearing (cf. Niamir-Fuller and Turner, 1999; Dong et al., 2011; Dong, 2016). The study employs an ethnographic approach involving qualitative data collection methods to examine the region-specific social-ecological factors that lead to such adverse circumstances and to illustrate how households cope with these conditions. Further, the study aims to generate hypotheses on how other households in the region can be prevented from experiencing similar hardships and how a pastoral way of life can be sustained in a post-colonial context characterised by ongoing rangeland degradation and the impacts of climate change. Ultimately, the paper discusses whether these social dynamics can be categorised as a social TP and whether this concept is helpful to analyse the observed processes.

The dryland pastoral system in focus

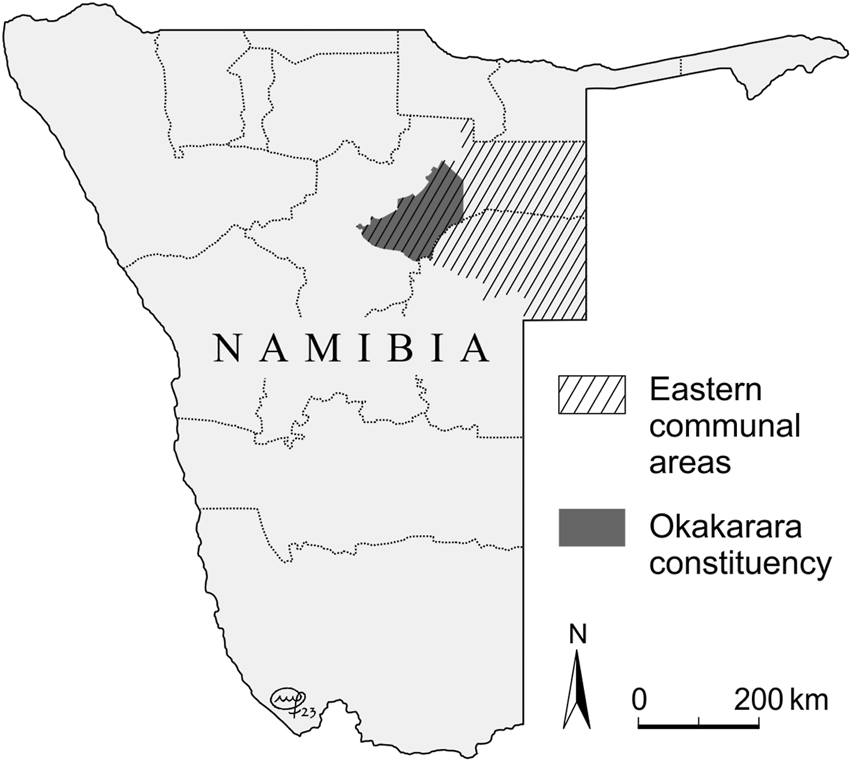

The pastoral system forming the focus of this research is situated in the semi-arid communal areas of eastern Namibia, with particular emphasis on the Okakarara Constituency (Figure 1). According to the last national census (2023), the region has an area of 14,644 km2, a population of ca. 31,000 individuals distributed across approximately 8,600 households, and a population density of 2.1 people per square kilometre. This makes it the most densely populated constituency in the eastern communal areas.1 Mostly, the population comprises Ovaherero pastoralists living in communities of 15–50 households with an average of 4.3 members each (Kakujaha-Matundu, 2003; Republic of Namibia, 2014). Primary income derives from selling livestock–mainly cattle, goats, and sheep–at town auctions. However, revenues are affected by fluctuating prices, livestock theft, and droughts (Hangara et al., 2011; Menestrey Schwieger, 2023). While livestock are typically slaughtered for own meat consumption only on special occasions, (e.g., funerals and weddings), cattle and, to a lesser extent, goat milk provide significant nutrition sources for several months annually (Kakujaha-Matundu, 2003). State transfers, such as old-age pensions, plus salaries and remittances from family members working in urban areas, are supplementary revenue sources. Horticulture (e.g., maize, beans, pumpkins) is limited because most gardens are irrigated by rainfall (Menestrey Schwieger, 2023). Average annual precipitation is 350mm, with volumes peaking between November and April (Mendelsohn and el Obeid, 2002). However, in recent decades, interannual rainfall variability has increased, leading to higher rainfall anomalies and more severe, widespread droughts that impact farming practices and ecosystem conditions (Turpie et al., 2010).

FIGURE 1

Location of the Okakarara constituency.

Historically, this region constituted part of the so-called “Native Reserve” in the Waterberg area (Köhler, 1959). The reserve was established by the South African colonial administration (1920–1990) in the 1920s to resettle survivors of the genocidal war against the Ovaherero communities (1904–1908) perpetrated by the former German colonial power (1885–1915) (Wagner, 1952; Werner, 1998). Subsequently, the reserve was incorporated into the larger Herero “homeland” in the 1960s as part of South Africa’s apartheid policies. These policies persisted until the country’s independence in 1990, when the homeland was declared communal land (Mendelsohn and el Obeid, 2002; Kakujaha-Matundu, 2003). Throughout the colonial period, this “reserve”, and later “homeland”, was designed to exert political and economic control over the Ovaherero through oppressive measures, including discriminatory taxation, exploitative labor recruitment, subjugation of leaders, and inadequate infrastructure development (Werner, 1993; Kössler, 2000). In addition, these areas were ecologically inferior to those allotted to white settlers, being deficient in phosphates and having few water sources (Werner, 1998).

Nowadays, ongoing challenges associated with multidimensional poverty, sectoral overpopulation, and rangeland overutilisation in the region are closely intertwined with the legacies of the aforementioned colonial interventions (Menestrey Schwieger and Mbidzo, 2020). Before these, the Ovaherero’s pastoral system resembled modern rotational grazing schemes, effectively preventing land degradation and supporting a thriving pastoral society (ibid.). Despite implementing various post-independence policies and programmes aimed at promoting rural development and ensuring sustainable rangeland management, progress in poverty reduction and land degradation has been limited (Kakujaha-Matundu, 2003). This is mainly because communal areas have largely preserved the structural layouts from the homeland era, especially regarding land use and availability. Problems include inadequate farming infrastructure like cattle posts with boreholes and emergency grazing zones, which encourage continuous grazing patterns (Kakujaha-Matundu, 2003). Moreover, fencing–particularly the construction of ‘camps’ to safeguard animals and secure land amid ongoing land competition–further affects access to grazing and reduces the overall communal grazing area (Stahl, 2009; Werner, 2015). In this post-colonial framework, communities face complex common-pool resource management problems in developing and implementing effective and sustainable rangeland management institutions at the settlement level (Menestrey Schwieger, 2022; Menestrey Schwieger et al., 2025).

Due to this combination of structural and local dynamics as well as climatic factors, the current landscape is characterised by high levels of encroaching woody plants, such as Senegalia mellifera, dominance of annual grass species with low grazing value, and large patches of bare ground (Strohbach, 2014; Brinkmann et al., 2023). Key, near-natural perennial grasses for grazing, such as Stipagrostis uniplumis and Eragrostis rigidor have virtually disappeared (Strohbach, 2014; Menestrey Schwieger et al., 2025). The situation is exacerbated by government regulations that have restricted removal of invasive woody plants from communal rangelands for almost 10 years (Brinkmann et al., 2023). Consequently, rangelands are shifting from primarily open savannahs to a patchwork of bush encroachment and barren areas (Tabares et al., 2020). Climate factors, including frequent droughts, have also contributed to these land degradation processes (ASSAR, 2018). Coupled with an anticipated 20% decrease in rainfall by 2050, these changes pose significant risks to livestock production and pastoral livelihoods on a large scale (Turpie et al., 2010).

Materials and methods

Despite the aforementioned developments, there are no reports of pastoralists losing their primary livelihood source, nor details on the processes causing these conditions. This lack of information sharply contrasts with the experiences documented by the author from elder herders before this study. In his earlier work on the human aspect of desertification in the region2, they often mentioned that households now have fewer animals than 30 years ago, with more families losing all their livestock. However, official data on livestock numbers could not corroborate these statements. According to Mendelsohn and el Obeid (2002), livestock numbers remained relatively stable between 1992 and 2001, but no later figures have been published. Efforts to evaluate recent declines in livestock numbers were unsuccessful, as multiple formal requests for data from government agencies went unanswered. Still, farmers in the nearby Omaheke region share the same observations (Siririka et al., 2025), and the area’s recent history of severe droughts (such as in 1981, 1992, 1995, 2013, 2019, 2024), as well as the significant loss of carrying capacity (up to 50% in some areas) due to bush encroachment (Brinkmann et al., 2023), lend credibility to their claims.

Given these circumstances, data collection and analysis relied mainly on local people’s observations and accounts. To this end, a combination of snowball and purposive sampling techniques was used to identify potential participants for this study and to gain a deeper understanding of the processes they experienced while losing all their livestock (DeWalt and DeWalt, 2002; Bernard, 2017). Accordingly, the research was guided by phenomenological thinking, focusing more on an in-depth understanding the mechanisms driving this phenomenon at the individual/household level as lived and described by participants, rather than evaluating quantitatively how close the overall pastoral system is to a social TP (Gill, 2020). Therefore, a small sample was selected and an exploratory approach was adopted using qualitative data collection methods to achieve rich data collection. This strategy also sought to gather sufficient longitudinal data to identify the context-specific factors and processes contributing to critical livestock losses from a social TP perspective (Hodbod et al., 2024). In doing so, it was assumed that both socio-economic and ecological/climatic factors significantly influenced pastoralists’ vulnerability to undergoing such transitions (cf. López-i-Gelats et al., 2016).

Sampling and data collection took place from early May to the end of June 2024 (a drought year). The process began with key informants from the author’s previous work in the region being contacted to identify individuals who had recently lost all their farm animals. The author was led to potential interviewees and further informants through this outreach, including local traditional authorities (ozorata) who maintain lists of vulnerable households needing government food aid. Through their assistance, additional potential cases were identified. Eventually, ten participants were selected: six without livestock, two with some livestock but feeling they had lost everything, and two rebuilding their herds. This diverse group was deliberately selected to thoroughly examine and provide meaningful perspectives on social TPs, especially regarding what these conditions mean to various individuals and how these TPs might potentially be reversed, aligning with the phenomenological approach.

The primary method to gather information was unstructured interviewing, which is well-suited for investigating relatively unexplored phenomena and capturing individuals’ lived experiences (DeWalt and DeWalt, 2002; Bernard, 2017). Interviewees, often accompanied by their family members, were encouraged by the author to speak freely and in detail about how they lost all or nearly all their livestock. He exercised minimal control during the interviews, primarily asking follow-up questions about specific dates, processes, and influencing factors. Participants were also encouraged to express how they sustained their livelihoods with little or no livestock and what this situation meant for their income and food security. Lastly, their perspectives were sought on possibilities of resuming livestock production or rebuilding their herds, considering the socio-economic and environmental circumstances in which they lived. In the cases of pastoralists actively rebuilding their herds, how this was possible and how the process had unfolded thus far were investigated. All interviews were audiotaped and conducted with the assistance of an Otjiherero-English translator. The recorded information was then transcribed and analysed through thematic coding using MAXQDA qualitative data analysis software. Initial coding categories included “drivers,” “consequences,” and “coping strategies” related to livestock losses; however, these were expanded with more specific sub-codes linked to the TP concept as the data was reviewed in greater detail. These sub-codes included “reinforcing factor,” “irreversible state,” and “requirement to reverse TP.” Subsequently, patterns and relationships among these codes were identified to develop a cohesive narrative. This analytical process was further supported by an extensive literature review to connect the interview data with regional structural and historical processes.

Results

Basic socio-economic characteristics of the sample

The ten cases analysed in this study include six men and four women, aged between 52 and 89 (see Table 1). The six cases without livestock had been without animals for varying periods, with one having lost its animals as early as 1994 and the others as recently as 2019. Before that, they had owned farm animals for about 20–60 years, most of which they received as inheritance and/or by purchase. The two cases of participants who still had some animals at the time of interview had two goats and two sheep, and 15 head of cattle, respectively. The two who were actively rebuilding their herds started this process in 2022. Despite their different circumstances, all had suffered substantial livestock losses, with the most extreme case involving losses of around 280 cattle and 200 goats.

TABLE 1

| Case | Main informant’s (MI) name, age, sex, and place of residence | No. of people living together | No. of livestock | No. of livestock losses | Without livestock since | Main source of subsistence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Simon 89, ♂ Omupanda | 3 (MI + spouse + 1 adult daughter) | 0 | 5 cattle 45 goats 9 sheep | 1994 | Old-age pension grants |

| 2 | Christine 83, ♀ Ohakane | 4 (MI + 3 adult sons) | 0 | 50 cattle 100 goats 100 sheep | 2012 | Old-age pension grant, occasional drought relief |

| 3 | Vetavi 57, ♂ Orunahi | (MI staying at his elder brother’s homestead) | 0 | 10 cattle | 2014 | Entirely depending on his elder brother |

| 4 | Fares 66, ♂ Okakarara | 2 (MI + spouse) | 0 | 18 cattle 20 goats | 2016 | Old-age pension grants, occasional income from sewing business |

| 5 | Nelson 53, ♂ Ohakane | 1 (MI alone) | 0 | 50 cattle 40 goats/sheep | 2019 | Occasional work, occasional drought relief |

| 6 | Berhnardine 53, ♀ Okarumatero | 7 (MI + 7 children, 2 below 18 years old) | 0 | 7 cattle 25 goats | 2019 | Child benefit grants, occasional work from adult children, occasional drought relief |

| 7 | Joe 72, ♂ Omupanda | 2 (MI + spouse) | 15 cattle (left) | 280 cattle 200 goats | (Most animals died in 2013) | Old-age pension grants, remittances from a child |

| 8 | Josephine 52, ♀ Okovimboro | 4 (MI + 3 small children) | 2 goats 2 sheep (left) | 70 cattle 40 goats/sheep | (Most animals died in 2019) | Occasional work, requesting neighbours for food |

| 9 | Gerson 85, ♂ Ombojumbonde | 2 (MI + 1 adult son) | 18 goats (since restart in 2022) | 13 cattle 63 goats 20 sheep | 2012 (but recovered in 2022) | Old-age pension grant, church pension, regular remittances from child |

| 10 | Katambo 65, ♀ Orunahi | 7 (MI + younger sister + MI’s grandmother’s brother + four grandchildren) | 11 goats (since restart in 2022) | 15 cattle 15 goats | 2019 (but recovered in 2022) | Old-age pension grants, occasional drought relief |

Basic characteristics of the sample.

Due to their livestock losses, all households faced food shortages, notably in cow’s milk–a crucial part of the Ovaherero diet–and the number of daily meals. Instead of the usual three meals, often maize porridge with sour milk (omaere) or potatoes with store-bought sauce or canned meat, most participants managed only one, sometimes two, meals, usually plain porridge. During this challenging period, households couldn’t grow food through gardening because of inadequate rainfall and high water costs from commercial providers serving only a few local communities. While some participants received occasional food relief, all reported that the general food scarcity was very stressful and negatively affected their mental wellbeing.

All informants primarily relied on income sources that typically supplement livestock earnings in the region, such as government transfers and/or remittances (cf. Menestrey Schwieger, 2023). This included those who still had a few animals or were actively trying to rebuild their herds. These informants would only sell or use their animals when absolutely necessary to preserve their remaining stock or allow the herds to grow. Extremely urgent situations encompassed severe food shortages or funerals due to the latter’s socio-religious significance (Durham, 2002; Kgatla and Park, 2015). These events often involve the slaughter of at least one animal (especially cattle and/or sheep) to honor the deceased’s transition into the realm of the ancestors and provide food for mourners. Furthermore, especially in cases where key informants received no government subsidy, they relied exclusively on odd jobs (e.g., building houses, housekeeping) and food donations from neighbours and the government to make ends meet. In one case, a 57-year-old informant, Vetavi, who neither received government aid nor found employment, had to join his older brother’s household to survive after losing all his animals. He had previously been self-sufficient, farming independently for over 20 years.

As with this example, all family compositions recorded during the research were impacted by livestock loss. In some instances, individual family members, such as an adult son or daughter of the main informant, had to leave because of reduced livestock income to find work and support their families. In other cases, most of the family left for the same reason, leaving only a few individuals to manage the homestead. Notably, two interviewees did not get support from those who had left, mainly because they couldn’t find income in their new location. Additionally, they were ineligible for government subsidies, which worsened their socioeconomic situation compared to others. This was the case for 52-year-old Josephine. She lived alone in a small hut on her husband’s homestead, caring for three children–two of her own and one from her ill sister. After losing nearly all their livestock in the 2019 drought, her husband and his extended family moved to Windhoek, and he was unemployed, unable to send money. Josephine struggled to manage her two goats and two sheep while feeding her children, sometimes cleaning a retired teacher’s house for cash, or maize milling, but such opportunities were rare. She kept her last animals in case she could not find food or as a final resort to “pay for transport to town and struggle there”.

Conversely, two cases involved individuals who initially left due to livestock losses or were already living and working elsewhere but chose to return to help their families care for their animals and prevent further depletion–an effort that ultimately proved unsuccessful. Additionally, there was one case where an individual returned specifically to help rebuild the herd. These examples will be briefly illustrated in the following sections. Finally, one participant stood out as an example of those who had left their homes and extended families behind. With hopes of someday resuming farming, he and his wife relocated to Okakarara town to start a small business and earn a living after their livestock on the family homestead diminished. Otherwise, all informants still lived in their home areas, regardless of their livestock situation.

Dynamics contributing to livestock losses

Participants lost livestock for multiple reasons, with droughts being the leading cause in all cases, except for one participant whose animals were lost mainly due to livestock theft and illness. In each instance, participants usually identified at least one other factor that worsened the effects of droughts, leading to the reduction of herds. These additional factors were linked to household constraints, such as insufficient financial and human resources to purchase supplemental feed and care for animals effectively. Other issues included inadequate decision-making, for example, failure to prioritise spending on animal care, and unforeseen circumstances like funeral associated expenses. Additional determinants mentioned were more contextual, relating to the social-ecological framework in which participants lived. These included livestock theft, ongoing degradation of rangelands, carnivore attacks (e.g., jackals, hyenas), inadequate drought support, lack of alternative grazing areas, and/or shrinking grazing lands due to population growth and fencing.

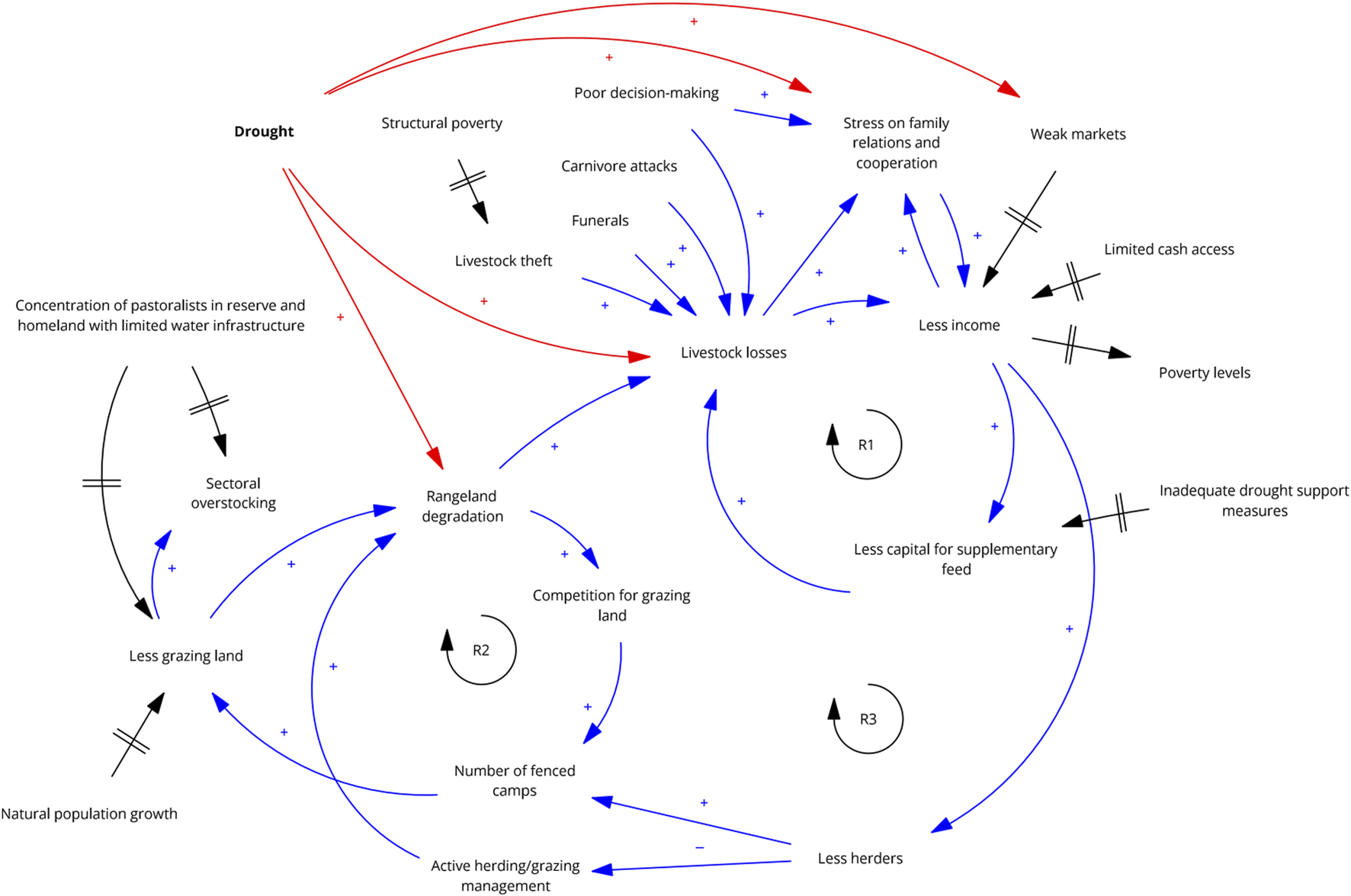

From a social TP perspective, these interactive processes resemble notions of ‘positive feedback loops’ and non-linearity (Milkoreit, 2023); that is, reinforcing mechanisms that promote a rapid change toward another undesirable state, which in our context would involve transitioning from having livestock to having no animals. To detail the complex interplay of these factors leading to livestock losses, I share the experiences of two individuals.

Example 1

When I first met 53-year-old Nelson, he was living alone on a homestead that had once housed his grandmother, three sisters, their children, and an uncle, totalling 13 family members. They had about 50 cattle, 40 goats, and sheep, which had served as their primary sources of income, alongside his grandmother’s pension. By the time we met, his grandmother had died, and the rest of the family had scattered. No animals were kept, and Nelson survived by helping to build huts for some cash or taking “any small job I could find,” as he put it. He received rations of porridge from neighbours. The 2004 drought significantly influenced this situation, but it was not the only factor.

During a similar drought 8 years earlier, Nelson’s family accessed grazing at a nearby community and a government farm after applying. However, by 2004, the population in that community had increased, and external users were no longer allowed. Moreover, obtaining a permit for the government farm became impossible due to the surge in applicants. Consequently, Nelson’s livestock had to remain in the settlement, where the grazing land was severely degraded. This forced him to sell several of his animals to buy supplementary feed, “but it was never enough”. To make matters worse, Nelson’s uncle sold several young cows during and after the drought “to solve his own problems”, putting his own needs ahead of the family’s welfare, further weakening the herd’s ability to recover. By the end of 2004, the family’s herd had dwindled to six cows.

In 2010, Nelson moved to a town 165 km away to find work and support his family, leaving them without their main herder. As a result, thieves stole a cow along with several calves while he was gone. In 2019, during a severe drought, Nelson returned home when his grandmother fell seriously ill and eventually died. To pay for the funeral, the family sold two cows, leaving them with only three. At this point, his sisters and uncle left for the towns seeking another source of livelihood, leaving Nelson behind. To save the remaining animals, Nelson took them to another uncle in a different community, hoping for better grazing conditions. Unfortunately, all three cattle died there due to the widespread effects of the drought, and Nelson lacked money to buy feed for them.

Example 2

In 2012, 83-year-old Christine lost her entire herd to drought, but she noted that “things started going bad” a decade earlier, in 2002. At that time, she lived with her late husband’s four siblings, their children, and grandchildren, totalling twenty people. The family owned approximately 50 cows, 100 goats, and 100 sheep, which provided their primary source of income, along with the pensions of Christine and her husband’s siblings. She remembered, “We lived like one big family; whenever we slaughtered a goat, we shared it.” However, during 2002, animals began to disappear more frequently, a phenomenon that Christine attributed to the local introduction of cell phones, which made it easier for livestock thieves to coordinate their thefts. Simultaneously, more people began to build “camps” to better protect their animals from being stolen. However, this gradually reduced the available grazing land within the settlement and “led to more damage to the land”, a trend that continues today, Christine emphasised. Then, in 2004, a drought resulted in fewer animals returning from the veld as less grazing was available. This dynamic, combined with the ongoing issue of cattle rustling, strained family ties as people became suspicious, accusing one another of secretly taking and selling animals. These conflicts were exacerbated by the need to sell livestock to raise cash for feed, prompting questions about whose animals should be sold to keep the rest alive.

Eventually, the drought ended, but relationships within the homestead were severely affected. The members decided to part ways, splitting the family herd and leaving Christine with her late husband’s nephew and two sons. When drought struck in 2012, she still had 18 goats and five cattle, which were challenging to save. An adult son working in town as a security guard returned to help her, but his efforts proved futile. Grazing in the village was depleted, and relocating the animals, leaving elderly Christine alone, was not an option. Ultimately, they lost all their animals due to drought and lack of funds to buy fodder that year; “since then, we all survive only from my pension,” Christine concluded.

Feedback loops

These examples illustrate how different households may face similar factors resulting in livestock loss. This is particularly evident in both cases as drought conditions intersected with challenges such as reduced access to grazing land, cattle theft, family issues, and financial constraints. Together, these factors lead to a rapid decline in livestock numbers. Like Nelson and Christine’s cases, other participants’ experiences with livestock loss were also unique in some ways, but shared notable similarities. One common aspect was the purchase of fodder to keep their animals alive. Except for the individual who lost animals to theft and illness, all took this step to protect their remaining herd. However, during dry seasons, animal prices usually decline in already weak markets that are difficult for pastoralists to access, meaning they need more animals to earn the same income. This often results in fewer animals and reduced capital, particularly as droughts persist amid rangeland degradation, limited grazing options, scarce cash access, and inadequate drought support measures for farmers, such as low subsidies for selling livestock and purchasing supplementary feed, which are not accessible to all farmers (Menestrey Schwieger, 2023). These processes, initiated and amplified by the drought, resemble the typical TP dynamic of ‘positive feedback loops’ previously mentioned (Figure 2, R1). Over time, as shown above, such developments can strain family relations and cooperation during critical periods, increasing households’ vulnerability to livestock loss.

FIGURE 2

Factors and feedback loops leading to livestock losses.

Simultaneously, these dynamics are connected to other structural factors that, although not directly triggered by drought, limit pastoralists’ capacity to sustain their livestock during such periods. They often have no choice but to buy supplementary feed, which is usually insufficient during these times. These factors include reduced rangeland, population growth, fencing, and livestock theft, as pointed out by participants. Such issues are tied to the legacies of colonial land and resettlement policies, socio-economic marginalisation, and the shortcomings of post-independence governments in adequately addressing these challenges (Menestrey Schwieger and Mbidzo, 2020). Throughout history, these forces have amplified through their own self-reinforcing mechanisms (Figure 2, R2): initially, the concentration of pastoralists in this former reserve and homeland, with limited water infrastructure, resulted in sectoral overstocking. Subsequently, natural population growth, less land available for farming, and heightened competition for grazing land, along with structural poverty, prompted people to set up camps to safeguard their animals and ensure access to grazing (Kakujaha-Matundu, 2003). These actions increased grazing pressure, which harmed rangeland conditions and livestock productivity, leading to higher poverty levels. More herders were forced to seek wage labour elsewhere–a pattern that began during colonial times when young men were compelled to find work outside their homeland to pay colonial taxes (Werner, 1998). By extension, this caretaker shortage results in less active herding and less effective grazing management (Figure 2, R3) (Menestrey Schwieger and Mbidzo, 2020). It also leads to more camps being set up to prevent livestock theft, which in turn reduces grazing land and causes more deterioration (Stahl, 2009).

Consequently, it is reasonable to suggest that these ongoing, historically embedded structural dynamics have created increasingly difficult conditions for pastoralists, hindering their ability to overcome droughts while suffering significant livestock losses. Essentially, these factors have consistently reduced their ability to handle such climate challenges within the post-colonial, social-ecological context of their farming practices, thereby increasing the risk of rapidly losing all their animals. As these cases illustrate, one prolonged drought in this setting can trigger a chain reaction leading to complete loss of animals. Since participants have been breeding farm animals for decades, and family herds are often inherited across generations (Gordon, 2005), this process of losing livestock can happen relatively rapidly, thus also reflecting the idea of abruptness from a TP perspective (Milkoreit, 2023).

Irreversible circumstances (?)

According to the TP logic, an essential feature of a TP process is “limited reversibility”, closely related to the timescale relevant to the individuals or communities involved (Milkoreit et al., 2018). In our case, this can be framed as the question of whether participants and families who have reached the state of being without livestock can resume livestock production or rebuild their herds within their lifetimes. If they cannot, they may have reached a social TP. While this question appears straightforward, it is difficult to provide a comprehensive answer since it is challenging to predict how the lives of the participants and their families will unfold in the coming years or decades, not to mention how the overall social-ecological context in which they live will progress alongside political and global dynamics. One way to get insight, however, is to illustrate the personal challenges, hopes, and expectations of participants regarding the possibility of returning to livestock farming or restoring their herds to their original sizes. This approach will highlight their viewpoints on what they view as irreversible and thus elucidate the subjective significance of a TP within their lived experiences.

Challenges of resuming livestock farming

Of the six cases in the sample where all livestock were lost, four participants were pessimistic about restarting livestock farming. Two remained hopeful, as illustrated below. Among the former, three actively tried to restart farming (Christine, Simon, Fares) but faced various challenges, while one indicated she lacked the means to even try (Bernhardine).

In Christine’s case, whose story was shared above, restarting was hindered by local livestock theft. After losing her livestock in 2012, she approached the household of her patrilineage for help and received 18 goats that still belong to her. However, soon after she returned to her homestead, the animals began to be stolen, and by 2016, she had none again. With her pension being the only income source for her and her dependants, alongside occasional drought relief, there was little chance of restarting livestock farming. When asked if she thought things could still take a positive turn in the future, she despairingly answered “aye” (no).

A little different was 89-year-old Simon’s attempt to restart livestock farming. He lost all his animals in 1994, mainly through drought. Since then, he, his wife, and their unemployed daughter have depended solely on their pension grants. Six of his eight grandchildren were in different towns; some unable, and some unwilling to help him, despite being employed. The other two were jobless. At one point, he concentrated on gardening to sell crops and buy some livestock. However, this failed due to high water costs from a government water supplier. He explained, “I used to sell whatever I planted, especially maize, but then the little vegetables I managed to grow and sell went toward paying the water bill.” Despite these struggles, he bought a donkey just before the 2019 drought, but it did not survive it. The only way to return to livestock farming, according to him, is “if the government gives me a few goats”.

Similarly, 66-year-old Fares and his wife attempted to return to livestock farming by setting up a sewing business in Okakarara with the intention of investing the profits in buying livestock. They financed this venture in 2016 with the money they made from selling their last goats. Most of their remaining animals were lost that year, mainly because of drought and livestock theft. At the beginning, “[the business] started well but now, it is going down”, Fares explained. Since 2019, the couple have received a pension grant, which helps cover their basic needs. However, to cover their business expenses and support their two children–who live with Fares’ older brother in a coastal city and attend school there–they had to take out a cash loan. This led them into a cycle of debt that they are struggling to repay due to high interest rates. Therefore, when asked about returning to livestock farming, Fares said, “We would love to, but only if we had the income to do so.”

Finally, 53-year-old Bernhardine lacked the resources to even attempt to return to livestock farming. When we met, five of her seven children were living in towns, surviving on temporary jobs. She depended mainly on child benefits from two of her children who lived with her, totalling N$700, along with occasional drought relief. She has no other relatives to turn to. Her last animal died during the 2019 drought, but their numbers had been declining for several years due to hyena attacks, theft and limited grazing. Since then, Bernhardine has focused on crop farming, but growing crops in her small garden is difficult due to seasonal, erratic rains. She could use water from a parastatal for irrigation, but cannot afford the utility bills. When asked if she wanted to farm with livestock again, she said that “without help, any new animals would face the same fate”.

These four participants’ reports indicate they might be facing irreversible conditions. Despite their efforts, restarting livestock farming was impossible for Christine, Simon, and Fares due to external barriers like livestock theft, high water costs, and challenges in maintaining their businesses and families. These issues prevented them from earning money to buy livestock and rebuild their herds. Bernhardine, by contrast, wanted to focus on other farming activities because she considered livestock farming unviable under her current socio-economic conditions. Additionally, the high cost of water needed for food production made her dependent on government grants to survive. Therefore, participants believed resuming a pastoral lifestyle was impossible without external intervention, such as government aid or water subsidies. This suggests that they have probably reached a social TP, as they cannot return to farming unless assisted (cf. Hodbod et al., 2024).

Hoping despite the circumstances

Unlike previous participants, the cases of Nelson and Vetavi show that reaching a negative social TP may also be a matter of perspective. Nelson–whose story was detailed earlier–was hopeful of resuming farming, despite having been without animals for almost 5 years and having survived on odd jobs and food handouts from neighbours. “My plan is to repair the kraal and fix the house, and then try to get livestock if I get a big tender to build a house,” he said. Resuming livestock farming is vital to him, as he explained: “I grew up farming; I never went to school, so farming is something I love. Not having a cow or any livestock really hurts my heart”. He believes that with just two female calves and perhaps five goats or sheep, he could resume farming. His plan involves having them “meet” a bull from another household on the veld so as to start breeding. Nonetheless, he would put more emphasis on the goats as the pasture is not in the best condition, and the rains have been poor. But he was also hopeful that “perhaps in 5 years’ time there would be good rains and more grass for the cows” and that in 7 years he would receive his pension, which might help him start his projects.

Similarly optimistic was Vetavi, who has been living with his older brother since losing all his livestock in 2014. “My brother helps me so that I do not starve, but he cannot do any more than that.” However, Vetavi hopes that once he starts receiving his pension in 3 years’ time, he will be able to save up to buy livestock and start farming independently again. “It’s really difficult because I don’t have any money to buy animals, but a pension would help a lot,” he said. Nevertheless, buying cattle seemed unrealistic as he estimated that it would take him at least 60 years to acquire ten animals for N$10,000 each. Therefore, focusing on smaller livestock was a more realistic starting point for him. Moreover, since small animals tend to withstand drought and adapt better to the current degraded conditions, he was confident he could gather them more quickly, start selling them someday, then reinvest in young cows to rebuild his herd to its former size, assuming the rainfall improves.

Consequently, these two accounts suggest that, from the participants’ perspective, being without livestock is only a temporary situation that can be reversed in the near future. From this emic view, a social TP may not have been reached since being without livestock is not permanent. However, despite their confidence in returning to livestock farming, Nelson and Vetavi rely heavily on external factors, particularly the hope of receiving an old-age pension, to change their situation. This detail is essential because a TP is considered such when external intervention becomes necessary to restore the previous state (Milkoreit, 2023; Hodbod et al., 2024). Therefore, from an etic perspective, they might have indeed reached a TP, as they seemingly cannot restart farming based solely on their own capacities. Moreover, it remains uncertain whether they can manage to resume livestock farming, especially cattle, given the financial aid situation and current rangeland conditions. However, as long as hope persists, they may still succeed despite the challenges.

Having animals is not a condition to restart or continue livestock farming

While earlier participants faced challenges in acquiring a few animals to restart farming, others, like Josephine and Joe, who still owned some, struggled to, or gave up on, rebuilding their herds. Consequently, they felt trapped in a situation that couldn’t be improved or reversed, suggesting that having livestock can still indicate that a social TP has been reached, or at least that pastoralists are on an unavoidable path toward it.

In the case of Josephine, whose story was shared earlier–caring for three kids without any financial support and living only on occasional work and food handouts–was not conducive to increasing their herd. She kept her last two goats and two sheep as a final resort, in case no food could be obtained, or if she needed to pay for transportation to town to find work. I explicitly asked her whether she thought she could have as many animals as she once did, but she only shook her head in despair.

In Joe’s case, he and his wife still had 14 head of cattle, which many locals would see as enough for livestock production and possibly for starting to rebuild his herd. However, Joe felt a deep sense of loss because he, his wife, and his late mother once had around 300 cattle and 200 goats before the 2014 drought, when much of the herd was lost due to starvation, or sold for feed. In this context, government support was unhelpful for Joe, who received only N$300 subsidy for selling a cow, and the discount for extra support was available only after paying the full amount. This did not motivate him to sell animals nor help him keep them alive. Therefore, the cattle they still owned came from a small group he had sent to a relative for grazing, about 200 km away, where they have been ever since.

Against this background, Joe had no ambitions to rebuild his herd, saying that he would be too old to care for them and that maintaining the number of animals he once had was no longer practical due to ongoing local land degradation. “Maybe two or three cows, so you can get some milk. Otherwise, I do not see how cattle can be kept here” he remarked. He would rather have goats and sheep “because they can survive better now that it does not rain much”. However, he pointed out that his and his wife’s pensions, plus occasional remittances from a daughter (who left as income from animals dwindled), are not enough to afford a herder. He emphasised that he was keeping his remaining animals with a relative as insurance for specific situations. “As a Herero person, you can’t sell everything, or you can’t be without cattle. If there’s a funeral, you need a cow; if there’s a wedding, you need a cow,” suggesting that without animals, these rituals would not have the same cultural significance.

These two examples show that owning livestock alone is not enough to rebuild herds. Several other factors are also important, including additional economic and human capital, as well as better rangeland conditions. Otherwise, even if pastoralists still have livestock, they may inevitably head towards a social TP of losing livestock. Notably, the emic perspective is particularly relevant in Joe’s case, given that he has already given up on livestock farming and rebuilding his herds despite having enough animals to do so. This emphasises that additional and variable case-specific conditions must be met before restarting livestock farming and rebuilding herds. His account also highlights that support for pastoralists during droughts is inadequate and may be difficult to access (Menestrey Schwieger, 2023).3 To provide insight into how resuming livestock rearing can practically work in the current social-ecological framework of this study, I provide relevant examples in the next section.

Restarting and rebuilding herds

Gerson, an 85-year-old retired pastor who dedicated himself to livestock farming after his church duties, once owned 13 cows, 63 goats, and 20 sheep. He lived with his son, who assisted with caring for animals, but eventually moved away for work, leaving him alone. Without a herder, Gerson’s cows started being stolen, one by one, until none remained. He hired a herder for the small stock to prevent the same issue, but the herd contracted an unidentified illness “so, every animal that died, I had to burn,” he recalled. Ultimately, only five goats and five sheep remained, but they produced no offspring. As a result, he sold them in 2012 and depended solely on his state old-age pension from then on. Ten years later, however, he managed to restart livestock farming by buying 15 goats, and had 18 when we met. He managed this by various means. After losing his livestock, he asked the church where he worked for help and started receiving a monthly pension of N$750. Additionally, a girl he once adopted, now an adult, found steady employment in tourism and started providing him with regular financial support. Therefore, through saving money over time and receiving external support, he was eventually able to gather enough to buy the animals. When I asked if he was planning to later farm with cattle too, he said “cattle is very expensive […] and the bushes are a lot, the rangeland is closed […] you won’t see much grass.” Therefore, given the current state of the rangeland where he lived, he would rather focus on goat farming. Fortunately, one of his adult sons, who used to live in the city, had returned to assist with the new animals. Gerson is optimistic that his herd will continue to grow, although it will probably not consist of the same kinds of animals as before.

Like Gerson, 65-year-old Katambo, who lived with her 63-year-old sister and 69-year-old uncle, was in the process of rebuilding their herd when we met. They once jointly owned 15 cattle and 15 goats, but lost most of them in the 2019 drought. Before that year, their small stock had almost been decimated by theft and by selling animals to buy supplements and salt to support their cattle. When drought struck, they lost all their cattle except one, which they decided to sell and use the money to buy six goats. This move helped them avoid becoming fully livestock-less, but they couldn’t rely on these animals for their livelihood. To prevent selling them, Katambo went to the capital to work as a housekeeper and sent money to her sister, who stayed at the homestead taking care of the animals. Meanwhile, the uncle was taken in by his nephews, who thought he would be better off with them. Other relatives, like Katambo’s and Hizembi’s children–eight in total–couldn’t offer support because they were unemployed, or couldn’t send money because they had their own children to care for.

However, almost 2 years later, Katambo began receiving her state old-age pension, as did her sister. Subsequently, she decided to return to the village, and soon, her uncle, who also received a grant, did the same. With all three receiving basic income, they could avoid using their animals for sustenance and let them reproduce. On the day of interview, the herd had increased to 13 goats. But for a jackal that killed two, there would have been 15. To better protect them, they wanted to get a shepherd dog. If things went well, Ketambo also wanted to buy a cow someday to get back to the 15 animals they had before, but “it all depends on God […] the lack of rain has affected us a lot. We hope that good rains will come back”, she said.

Accordingly, these two examples confirm that restarting livestock farming and rebuilding herds require particular economic and human capital. These capital assets are generally crucial for pastoralists in the broader region to cope and adapt to climate change impacts, such as Ovahimba, Damara, Nama in Namibia, as well as Griqua and other mixed-descent groups in South Africa (Ntombela et al., 2024). In both cases presented, the process of restarting and/or rebuilding herds is strongly supported by external input, with old-age pensions from the state playing a crucial role. Without them, participants probably would have had difficulty restarting livestock farming to rebuild their herds, just like other participants in this study who did not receive any grants. This means that, for recovery from a TP, at least in these two cases, this type of capital was crucial. In other cases within this study, additional factors (e.g., herders) might also be relevant. However, whether Gerson and Katambo will manage to rebuild their herds to their previous level remains uncertain, as other problems such as livestock theft and carnivore attacks are still present. Moreover, both of them are sceptical about restarting cattle farming due to rangeland conditions and current rain patterns, which again suggests their herds might not consist of the same animals and numbers as before. Therefore, if these external factors are left unaddressed or do not improve, individuals might be unable to recover fully, or in the same way, from a social TP within the current social-ecological framework.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to analyse the processes that pastoralists experience when losing their livestock from a social TP perspective using an ethnographic case study approach. In doing so, I illustrated the reinforcing mechanisms that cause the rapid loss of livestock among participants. These mechanisms include a combination of factors, with droughts being one of the most critical drivers, along with other determinants that amplify their effects. These amplifying factors are related to the social-ecological framework in which pastoralists live and farm, as well as household characteristics and decision-making. It was highlighted that colonial legacies related to land distribution and resettlement have created conditions that make it very hard for pastoralists to cope with drought and livestock losses. This, alongside population growth, and reduced chances to access grazing, has limited their options to manage drought by buying supplementary feed for their animals, which, in a context of poverty, limited access to job markets, and ongoing rangeland degradation, is of little help in keeping animals alive. Therefore, one could argue that Namibia’s post-colonial political economy and prolonged droughts caused by climate change are increasing the vulnerability of pastoralists and significantly influencing social TP processes of livestock loss at the local level. This situation is not only typical for the pastoral system in the study region but also for other pastoral communities in Namibia, such as the Ovahimba in northern Kunene (Inman et al., 2020) and globally, like the Maasai in Kenya or Khalkh Mongols in Mongolia (Muhammad et al., 2019).

Additionally, I explored the aspect of irreversibility, a key feature of TPs, by considering participants’ experiences after losing livestock and their efforts to restart livestock farming and rebuild their herds. From these analyses, it emerged that some participants have independently tried to restart livestock farming in different ways, but they have not succeeded for various reasons, such as livestock theft and difficulties generating income from other activities. From the cases presented, it is clear that individuals under 60 who do not receive pension grants, lack support networks, and have dependents—such as young children, as seen among female participants in this study—face major challenges in their recovery. Consequently, without human and economic capital, they are ‘stuck’ in a situation where resuming a pastoral lifestyle seems impossible without external intervention or structural changes, which indicates they have reached a social TP (Milkoreit, 2023; Hodbod et al., 2024). Conversely, it was highlighted that owning animals is not always essential for maintaining livestock farming, including reestablishing herds, if economic, human, and ecological challenges remain. In these cases, participants were probably on an inevitable path to a social TP of livestock loss despite possessing animals. Eventually, cases of participants actively restarting and rebuilding their herds–that is, recovering from a social TP–demonstrated that external financial aid, especially old-age pensions and networks, can be crucial. Without them, other participants in the study had much more difficulty restarting livestock farming, let alone securing their livelihoods. This reinforces the idea that various economic and human assets are essential for pastoralists to manage critical TP situations, assuming that at least a minimum critical level of natural capital is still available (Ntombela et al., 2024).

Recovery pathways and policy implications

By extension, it remains uncertain whether those restarting their herds will recover the same number and variety of animals, especially given ongoing rangeland degradation and climate uncertainties. In this regard, further research will be needed to explore how the regional social-ecological system will evolve and whether participants’ efforts to reverse social TP of livestock loss can be effective. For now, it seems that some key characteristics of the system, particularly cattle farming, might shift toward small stock farming as a way to adapt to ongoing and future environmental changes. Similar transformations have already been observed in other pastoral systems, such as among the Pokot in Kenya, for comparable reasons (Bollig and Österle, 2013). If this is the case, we could argue that the system might be shifting toward a different stable state, implying the crossing of an interim tipping point (Walker and Meyers, 2004).

Regardless of this, the cases examined indicate that without intervention–such as addressing structural reinforcing mechanisms and providing financial support to vulnerable pastoralists–people will keep struggling to prevent and reverse social TPs related to livestock loss at the household level. Given the negative impacts of anthropogenic climate change on the rangeland ecosystem and livestock farming in the near future (ASSAR, 2018), it is imperative to implement these interventions promptly. Such urgency is crucial to avert a large-scale social TP, as household-level TPs may indicate that the pastoral system is collapsing.

A key finding of this study is that droughts significantly contribute to livestock losses in the post-colonial context in which pastoralists operate, leaving them with limited mitigation options. Aside from buying supplementary feed, other strategies, such as moving livestock to protected grazing areas, are not feasible due to limited land and infrastructure, notably water supply. In this context, financial incentives and support for livestock owners to de-stock in the face of an imminent drought should be enhanced. Providing subsidies for supplementary feed as lower purchase prices rather than refunds after purchase would be more effective for farmers. Addressing these issues would give pastoralists more options for managing droughts effectively.

Moreover, Namibia’s post-independence government has implemented land reform initiatives aimed at expanding communal areas by acquiring neighbouring freehold lands, thus providing access to grazing and relieving pressure on the former ‘homelands’. However, this reform process has been very slow and needs to be sped up to effectively ease pressure on the former ‘homelands’ rangelands (Nghitevelekwa, 2020). These efforts, which are already championed by various Ovaherero leadership organisations (e.g., Ovaherero Traditional Authority) should be accompanied by programmes to support and implement feasible and sustainable rangeland restoration projects that align with current socio-economic conditions and capabilities. Recent ideas involve addressing rangeland degradation through a participatory split grazing approach at the settlement level, which includes grass reseeding and bush-thinning measures, the latter of which have been restricted for several years (Menestrey Schwieger, 2025). However, implementing a pilot project of this kind is very challenging if government and development agencies are not involved and supportive.

Eventually, initiatives like the nationwide basic income grant–widely discussed in Namibia recently and proven effective in reducing poverty, child malnutrition, and stimulating small-scale local economic activity (Haarmann et al., 2019) – as well as efforts to build a supportive socioeconomic environment and infrastructure for horticulture, would offer practical assistance to pastoralists in securing their livelihoods and living with dignity. For these purposes, only political will is needed.

Usefulness of the social TP concept

Finally, a few remarks on the usefulness of the social TP concept to analyse the observed processes in this research. Most likely, this study could have been carried out without relying on the concept of social TP to describe and analyse the observed processes. To underline that people are losing their main livelihood source and to stress the difficulties they face in maintaining or restoring a pastoral lifestyle, the social TP concept might not be essential. Nonetheless, like other scientific concepts, such as resilience and vulnerability, it provides a different perspective for examining societal dynamics and helps focus on particular aspects and processes (Grove, 2018). For instance, by applying the notion of ‘positive feedback loops’ to how and why pastoralists lost their livestock, it helped identify and better understand the sequence and connections of events and factors that caused such a critical transition in pastoralists’ livelihoods. This was especially evident regarding historical and structural factors that weaken pastoralists’ capacity to handle and recover from droughts, as well as the limited effectiveness of buying supplementary feed during these times within the existing social-ecological context. Once these loops are distinctly identified, they can then be halted, allowing for the development of more precise measures and changes to assist pastoralists.

Similarly, the discussion of non-linearity and abruptness is also relevant here. In the context of climate change, some critics argue that the TP concept is unsuitable since climate change involves cumulative harm. They believe that focusing on the immediacy and abruptness associated with the TP can mislead the public’s understanding of climate science. However, its usage can also prompt decision-makers to recognise the potential for rapid and serious changes in the climate system, an aspect that should be considered in responsible and accountable policymaking (Crucifix and Annan, 2019). In our context, however, this logic may have a more nuanced application. As shown, the social TP of losing livestock is influenced by socio-historical and environmental factors, which have reduced the resilience of pastoralists and their ability to overcome social and ecological challenges. While it may be debatable whether these contextual factors involve non-linearity and sudden changes, it is clear that they can lead to rapid and often irreversible livestock losses for pastoralists after a single drought. From this perspective, if these shifting livelihood conditions do not exemplify a social TP, it hard to imagine what would. Furthermore, if recognising such processes as TP helps mobilise decision-makers to act and prevent these transitions, why not conceptualise them as such? Consequently, the TP concept applied to examine livestock loss cases at the household level, as in this study, can be valuable in many ways. However, if the concept is helpful for analyzing other social phenomena, it must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Ultimately, a quantitative study to determine whether, and why, more and more households in the region have recently lost livestock could provide valuable insight into whether the entire pastoral system is heading towards a large-scale social TP. Such a study could also help to validate and expand on the factors causing this, as identified here. However, such an endeavour may involve overcoming problems of data availability and accessibility. Similarly, quantitative research establishing whether pastoralists are shifting from cattle farming to goat farming and focusing more on horticulture to sustain their livelihoods may indicate that important parts of the pastoral system are changing in response to ongoing social and ecological challenges. The case studies presented here suggest that these trends may already be happening and could serve as early warning signs of the broader system reaching a TP. Alternatively, they could also demonstrate the ingenuity of pastoralists in reorganising and adapting to the new conditions brought about by the Anthropocene–a resilience-building process also seen in other groups, which should be supported (Semplici et al., 2024).

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The National Commission on Research, Science and Technology in Namibia, an autonomous body entrusted with ensuring the integrity and ethical conduct of social research in the country. The Commission formally endorsed this research under permit number RPIV010422038. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study, including the publication of any potentially identifiable data included in this article.

Author contributions

DM designed and executed this research, including data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Funding was received from the German Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (NamTip; grant number 01LC2321C) and the German Research Foundation (project number 550924554).

Conflict of interest

The authors(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Footnotes

1.^See https://nsa.org.na/census/otjozondjupa-region/

2.^This work was done within the framework of the research project NamTip. For more information see https://www.uni-potsdam.de/en/namtip/

3.^“Drought relief policy frustrates Omaheke farmers”, New Era newspaper article, 04.06.2014.

References

1

ASSAR (Adaptation at Scale in Semi-Arid Regions) (2018). What global warming of 1.5 °C and higher means for Namibia. Available online at: https://assar.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/content_migration/assar_uct_ac_za/2465/files/1.5DEG_Namibia_WEB.pdf.

2

BernardH. R. (2017). Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

3

BestelmeyerB. T.OkinG. S.DuniwayM. C.ArcherS. R.SayreN. F.WilliamsonJ. C.et al (2015). Desertification, land use, and the transformation of global drylands. Front. Ecol. Environ.13, 28–36. 10.1890/140162

4

BolligM.ÖsterleM. (2013). “The political ecology of specialisaton and diversification: long-Term dynamics of pastoralism in east pokot district, Kenya,” in Pastorlism in Africa: past, present and futures. Editors BolligM.SchneggM.WotzkaH. P. (Oxford: Berghan Books), 289–315. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qcrb7.15.

5

BrinkmannK.Menestrey SchwiegerD. A.GriegerL.HeshmatiS.RaucheckerM. (2023). How and why do rangeland changes and their underlying drivers differ across Namibia’s two major land-tenure systems?Rangel. J.45, 123–139. 10.1071/RJ23007

6

CrucifixM.AnnanJ. (2019). “Is the concept of ‘tipping point’ helpful for describing and communicating possible climate futures?,” in Contemporary climate change debates: a student primer. Editor HulmeM. (London: Routledge), 23–35.

7

CrutzenP. J. (2006). “The anthropocene,” in Earth system science in the anthropocene. Editors EhlersE.KrafftT. (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer), 13–18. 10.1007/3-540-26590-2_3

8

CrutzenP. J.StoermerE. (2000). The anthropocene. IGBP Newsl.41, 17–18.

9

DakosV.MatthewsB.HendryA. P.LevineJ.LoeuilleN.NorbergJ.et al (2019). Ecosystem tipping points in an evolving world. Nat. Ecol. and Evol.3, 355–362. 10.1038/s41559-019-0797-2

10

DakosV.BoultonC. A.BuxtonJ. E.AbramsJ. F.Arellano-NavaB.Armstrong McKayD. I.et al (2024). Tipping point detection and early warnings in climate, ecological, and human systems. Earth Syst. Dynam.15, 1117–1135. 10.5194/esd-15-1117-2024

11

David TàbaraJ.FrantzeskakiN.HölscherK.PeddeS.KokK.LampertiF.et al (2018). Positive tipping points in a rapidly warming world. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain.31, 120–129. 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.01.012

12

DeWaltK. M.DeWaltB. R. (2002). Participant observation: a guide for fieldworkers. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

13

DietzS.RisingJ.StoerkT.WagnerG. (2021). Economic impacts of tipping points in the climate system, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.118, e2103081118. 10.1073/pnas.210308111

14

DongS. (2016). “Overview: pastoralism in the world,” in Building resilience of human-natural systems of pastoralism in the developing world: interdisciplinary perspectives. Editors DongS.KassamK.-A. S.TourrandJ. F.BooneR. B. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 1–37. 10.1007/978-3-319-30732-9_1

15

DongS.WenL.LiuS.ZhangX.LassoieJ. P.YiS.et al (2011). Vulnerability of worldwide pastoralism to global changes and interdisciplinary strategies for sustainable pastoralism. Ecol. Soc.16 (2), art10. 10.5751/es-04093-160210

16

DurhamD. (2002). Love and jealousy in the space of death. Ethnos67, 155–179. 10.1080/00141840220136800

17

Fernández-GiménezM. E.VenableN. H.AngererJ.FassnachtS. R.ReidR. S.KhishigbayarJ. (2017). Exploring linked ecological and cultural tipping points in Mongolia. Anthropocene17, 46–69. 10.1016/j.ancene.2017.01.003

18

FloresB. M.MontoyaE.SakschewskiB.NascimentoN.StaalA.BettsR. A.et al (2024). Critical transitions in the amazon forest system. Nature626, 555–564. 10.1038/s41586-023-06970-0

19

GillM. J. (2020). “Phenomenological approaches to research,” in Qualitative analysis: eight approaches. Editors Mik-MeyerN.JärvinenM. (London: Sage), 73–94.

20

GordonR. (2005). The meanings of inheritance: perspectives on Namibian inheritance practices, windhoek: legal assistance center (gender research and advocacy project).

21

GranovetterM. (1978). Threshold models of collective behavior. Am. J. Sociol.83, 1420–1443. 10.1086/226707

22

GrodzinsM. (1957). Metropolitan segregation. Sci. Am.197, 33–41. 10.1038/scientificamerican1057-33

23

GroveK. (2018). Resilience. London: Routledge.

24

HaarmannC.HaarmannD.NattrassN. (2019). “The Namibian basic income grant pilot,” in The palgrave international handbook of basic income. Editor TorryM. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 381–395. 10.1007/978-3-031-41001-7_19

25

HangaraG. N.TeweldemedhinM. Y.GroenewaldI. B. (2011). Major constraints for cattle productivity and managerial efficiency in communal areas of Omaheke region, Namibia. Int. J. Agric. Sustain.9, 495–507. 10.1080/14735903.2011.603516

26

HodbodJ.MilkoreitM.BaggioJ.MathiasJ.-D.SchoonM. (2024). “Principles for a case study approach to social tipping points,” in Positive tipping points towards sustainability: understanding the conditions and strategies for fast decarbonization in regions. Editors TàbaraJ. D.FlamosA.MangalagiuD.MichasS. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 79–99. 10.1007/978-3-031-50762-5_5

27

InmanE. N.HobbsR. J.TsvuuraZ. (2020). No safety net in the face of climate change: the case of pastoralists in Kunene region, Namibia. PLoS ONE15, e0238982. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238982

28

Kakujaha-MatunduO. (2003). Common pool resource management: The case of the eastern communal rangelands in semi-arid Namibia. Maastricht Shak. Pub.

29

KeysP. W.GalazV.DyerM.MatthewsN.FolkeC.NyströmM.et al (2019). Anthropocene risk. Nat. Sustain.2, 667–673. 10.1038/s41893-019-0327-x

30

KgatlaS. T.ParkJ. (2015). Healing in Herero culture and Namibian African independent churches. Theol. Stud.71, 1–9. 10.4102/hts.v71i3.2922

31

KöhlerO. (1959). A study of otjiwarongo district (south West Africa). Pretoria: Department of Bantu Administration.

32

KoppR. E.ShwomR. L.WagnerG.YuanJ. (2016). Tipping elements and climate–economic shocks: pathways toward integrated assessment. Earth's Future4, 346–372. 10.1002/2016EF000362

33

KösslerR. (2000). From reserve to homeland: local identities and South African policy in southern Namibia. J. South. Afr. Stud.26, 447–462. 10.1080/713683582

34

LentonT. M. (2011). Early warning of climate tipping points. Nat. Clim. Change1, 201–209. 10.1038/nclimate1143

35

LentonT. M. (2013). Environmental tipping points. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour.38, 1–29. 10.1146/annurev-environ-102511-084654

36

LentonT. M. (2023). “Climate change and tipping points in historical collapse,” in How worlds collapse: what history, systems, and complexity can teach us about our modern world and fragile future. Editors CentenoM. A.CallahanP. W.LarceyP. A.PattersonT. S. (New York: Routledge), 261–280.

37

LentonT. M.Armstrong McKayD. I.LorianiS.AbramsJ. F.LadeS. J.DongesJ. F.et al (2023). The global tipping points report 2023. Exeter (Exeter, United Kingdom University of Exeter). Available online at: https://report-2023.global-tipping-points.org/.

38

LewisS. L.MaslinM. A. (2015). Defining the anthropocene. Nature519, 171–180. 10.1038/nature14258

39

López-i-GelatsF.FraserE. D. G.MortonJ. F.Rivera-FerreM. G. (2016). What drives the vulnerability of pastoralists to global environmental change? A qualitative meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Change39, 258–274. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.05.011

40

MathewsA. S. (2020). Anthropology and the anthropocene: criticisms, experiments, and collaborations. Annu. Rev. Anthropol.49, 67–82. 10.1146/annurev-anthro-102218-011317

41

MendelsohnJ.el ObeidS. (2002). The communal lands in eastern Namibia. Windhoek: RAISON.

42

Menestrey SchwiegerD. A. (2022). Exploring pastoralists’ perceptions of desertification tipping points in Namibia’s communal drylands: an ethnographic case study from okakarara constituency. Pastoralism12, 3. 10.1186/s13570-022-00231-x

43

Menestrey SchwiegerD. A. (2023). Overcoming Namibia's worst drought in the las 40 years: ethnographic insights from okakarara constituency. J. Namib. Stud.33, 31–56. 10.59670/jns.v33i.272

44

Menestrey SchwiegerD. A. (2025). Addressing rangeland degradation in Namibia’s communal areas. Hum. Organ., 1–14. 10.1080/00187259.2025.2540111

45

Menestrey SchwiegerD. A.MbidzoM. (2020). Socio-historical and structural factors linked to land degradation and desertification in Namibia's former Herero 'homelands. J. Arid Environ.178, 104151. 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2020.104151

46

Menestrey SchwiegerD. A.Munyebvu - ChambaraF.HamunyelaN.TielbörgerK.NesonganoW. C.BiltonM. C.et al (2025). Understanding rangeland desertification at the village level: a comparative study with a social-ecological systems perspective in Namibia. Hum. Ecol.53, 53–72. 10.1007/s10745-025-00574-0

47

MilkoreitM. (2023). Social tipping points everywhere? Patterns and risks of overuse. WIREs Clim. Change14, e813. 10.1002/wcc.813

48

MilkoreitM.HodbodJ.BaggioJ.BenessaiahK.ContrerasR. C.F. DongesJ.et al (2018). Defining tipping points for social-ecological systems scholarship—an interdisciplinary literature review. Environ. Res. Lett.13, 1–12. 10.1088/1748-9326/aaaa75

49

MuhammadK.MohammadN.AbdullahK.MehmetS.AshfaqA. K.WajidR. (2019). Socio-political and ecological stresses on traditional pastoral systems: a review. J. Geogr. Sci.29, 1758–1770. 10.1007/s11442-019-1656-4

50

MukherjiR. (2013). Ideas, interests, and the tipping point: economic change in India. Rev. Int. Political Econ.20, 363–389. 10.1080/09692290.2012.716371

51

NathanA. (2013). China at the tipping point? Foreseeing the unforeseeable. J. Democr.24, 20–25. 10.1353/jod.2013.0012

52

NghitevelekwaR. (2020). Securing land rights: communal land reform in Namibia. Windhoek: University of Namibia Press.

53