Abstract

Dominant global discourses on climate change often define vulnerability and risk through a modern sedentarist framework, rooted in a human/nature dichotomy and a unified model of selfhood shaped by European modernist thought. These premises do not hold for Nuer pastoralists and refugees in South Sudan, whose relational selfhood remains rooted in sacrificial practice, and in their dense ties with cattle, divinities, climate, ancestors, descendants, and the shared substance that binds them, “blood.” As they confront intensifying climate shocks and armed conflict, Nuer communities work to steer their destiny by drawing on alternative cattle resources and sustaining relationships that extend beyond their home rangelands, thereby protecting what they understand as their vulnerable blood. This article focuses on those who have lost or left their cattle in the village; it examines how their cattle-based rituals and moral practices help them navigate crises of self. Drawing on long-term, multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork (2009–2018, South Sudan and Uganda), this study posits these practices as a form of “climate narrative” that offers alternative methods by which to understand vulnerability and crisis as socially and spiritually entangled experiences. Through case studies of newly emergent sacrificial practices—such as remote sacrifices and lime substitutions—the study demonstrates the centrality of “blood” as a connective force linking humans with divinities, the rain, cattle, and fruits. The Nuer understanding of human vulnerability, based on the fluidity and pervasive nature of “blood,” enables a resilient and sustainable collective self. This relational selfhood and perception of crisis offer a critical perspective on the global “climatisation” of crisis, which is grounded in Eurocentric notions of selfhood and vulnerability. The international communities also should place greater value on the capacities required to live with uncertainty in the Anthropocene.

Introduction

In late 2012, at the onset of the dry season in South Sudan—when the land still retained water and the earth remained sodden—my host father observed a small whirlwind forming in our backyard and remarked: “Look at that strong spiral of wind. When winds like that appear, it means a conflict is breaking out somewhere. The kuɔth (the divinity) knows this and is letting us know.” Jonglei State, where we lived at that time, saw repeated armed clashes. Flooding compounded the crisis and displaced large numbers of people, including several who took shelter in our home after fleeing rural areas. The Nuer interpret climatic changes and natural phenomena—such as wind and rain—as messages from kuɔth. This divinity governs both human happiness and misfortune alike, with the cattle—central to their pastoralist life—serving as an essential medium of communication.

“Cherchez la vache” (“Look for the cow”) was once considered the best advice for understanding the behaviour of Nuer pastoralists (Evans-Pritchard, 1940). The concept of the “cattle complex” (e.g., Herskovits, 1926), which highlights the inseparability of pastoralist life and cattle, underscores their profound economic, social, religious, and moral significance among the Nuer. However, these classical studies on pastoralists, which were grounded in synchronic community analyses, have been criticized for producing an image of pastoralists as living within static cosmologies and closed value systems, lacking perspectives on historical dynamics including colonialism and cultural transformation (Johnson, 1981; Johnson, 1982a; Johnson, 1982b; Hutchinson, 1996; see also Rosaldo, 1986). Subsequent studies on the Nuer focusing on social changes have revealed the cosmological dynamics and the continuity of cultural idioms and concepts and pointed out the continuity of human/cattle equality in the scene of monetary economy, homicide in civil wars, and religiosity. Relatedly, the concept of blood—riɛm in the Nuer language—has become central to their current experience of social upheaval. As they confront rapid change and recurrent crises, the people debate whether new media and emerging practices can possess or purify blood in the way cattle or humans once did (Hutchinson, 1992a; Hutchinson, 1992b; Hutchinson, 1996). Riɛm is not merely a biological substance or a symbol of life; it shapes the self, grounds human existence, and anchors the very conditions of experience. Anthropological approaches to crisis in Eastern African pastoral societies, including those addressing the climate crisis, highlight the importance of local understandings. Yet the role of the self and selfhood in shaping how people experience and respond to social and environmental change remains largely unexplored.

For the Nuer, selfhood is inseparable from cattle, kin, and divinities—a perspective that we might frame as a “relational self” where existence, self, and identity, are not static but dynamically constituted through relations with other beings and forces. Since South Sudan gained independence in 2011, Nuer pastoralists have endured persistent armed conflicts and severe flooding. Many have lost their cattle and other livestock, leading not only to material loss but also to profound moral and spiritual crises—crises traditionally addressed through cattle-related practices. In contrast to the vulnerabilities and coping strategies envisioned by the international community, the Nuer have sought to confront existential vulnerability—rooted in the absence of cattle—through newly emerging cattle-related practices. This study aims to examine how the Nuer’s concept of blood enables them to address vulnerability and sustain constitutive selfhood, by analysing cattle-related practices among Nuer refugees in the aftermath of the 2013 conflict and subsequent flooding.

This study addresses the following questions: Without their cattle, how do Nuer pastoralists cope with and manage moral and spiritual crises in an era of displacement? What roles do cattle, divinity, and sacrifice play in shaping concepts of vulnerability and crisis outside their homeland? I explore how the Nuer have sought to confront existential vulnerability—rooted in the absence of cattle—through newly emerging cattle related practices. The analysis is grounded in the following three arguments:

Even among refugees and migrants, selfhood remains deeply intertwined with the moral and spiritual influence of others, which may be described as a collective and relational selfhood. This becomes particularly evident in sacrificial practices conducted in the absence of cattle, where immoral actions are believed to affect not only the individual who commits them but also their relatives and descendants.

The Nuer concept of blood, riɛm, has long been interpreted within a framework that casts cattle and humans as equals. Traces of that perspective remain. Yet in a present shaped by the absence of cattle, ongoing crisis, and widespread displacement, the range of relations carried by this fluid, substance now stretches beyond that older framework. Riɛm increasingly encompasses ties to plants, the soil, and climatic forces.

In contrast to prevailing climate discourses in South Sudan (based on individualistic notions of selfhood and vulnerability), Nuer selfhood is relational and embedded within a broader ontological network involving divinities, animals, plants, natural phenomena, and thier components. The Nuer’s ubiquitous and fluid selfhood, grounded in notions of blood and divinity, challenges modernist assumptions about vulnerability and crisis that continue to rely on sedentarist ideals of stability and rootedness.

In the context of climate change, and in proposed solutions such as the Paris Agreement, adopted at COP21 in 2015, the “traditional knowledge” of local communities has been highlighted (Foyer et al., 2017). Yet, only those elements of traditional culture that appear superficially useful tend to be selected, while the deeper cultural logic remains insufficiently examined. Our task is not only to describe how local people think, but to ask why they think in such ways, and what ontological grounds underpin their practices. By pursuing this line of inquiry and critically examining our own ontological assumptions, we can explore what the “crisis” and “vulnerability” of human entail.

Scholars have noted discrepancies between the global discourse on climate change and local perception within African pastoral societies (e.g., de Wit, 2020; Schnegg, 2021; Ntumva, 2022). The application of global climate discourse to local communities has been critically examined through the concept of climatisation—a process in which individual or local predicaments are reframed as part of a global issue. This reframing often positions specific populations as “victims” and reproduces a standardised notion of “crisis” embedded in international rhetoric (Foyer, 2016; Foyer et al., 2017). For instance, in South Sudan, other pressing issues such as lack of education, healthcare, infrastructure, political instability, and poverty tend to often be framed within the discourse of climate crisis. Such discursive forms not only shape definitions of crisis but also obscure structural inequalities rooted in global economic and political systems (Ferguson, 1990; Roe, 1994; Rottenburg, 2009).

In the context of both climate change and forced migration, aid recipients are framed as atomised individuals who are either “victims” or “beneficiaries.” Within standardised UN humanitarian frameworks, vulnerability is not simply identified but produced, redefined, and perpetually reproduced. This mechanism results in the ongoing generation of so-called “vulnerable populations,” while often ignoring relational or collective forms of resilience and risk mitigation. To address these limitations, current ethnographies of ontology1 offer a critical framework for rethinking the entrenched dichotomies of modern European thought such as human/nature, individual/community, and passive/active agency (Viveiros de Castro, 1992; Viveiros de Castro, 1998; Viveiros de Castro, 2015; Viveiros de Castro, 2016; Willerslev, 2007; Kohn, 2007; Kohn, 2013; Haraway, 2008). Importantly, the numerous and varied metrics of “vulnerability” and “resilience” are inherently context-dependent, resisting universal application. This raises critical anthropological questions: What is vulnerability? How do local people perceive human vulnerability or crisis? How do they manage and respond to these challenges?

Anthropological research on climate change has aimed to recover the multi-layered complexity of human experiences as shaped by national and global policies (Brown, 1999; Crate, 2008a; Crate, 2008b; Crate, 2011; Orlove, 2009; Brüggemann, 2020). These studies have emphasised that understanding crisis requires more than experts and practitioners applying externally defined criteria of vulnerability. Instead, it necessitates attention to local ideas, perceptions, and concerns.

The concept of a “climatic lens” was introduced, through which diverse and sometimes unrelated issues—such as conflict, displacement, or social development—are reframed as climate-related problems (Foyer, 2016; Foyer and Kervran, 2017; Foyer et al., 2017). Once reinterpreted through this lens, such issues are subjected to the logic of global climate governance and intervention.

The conditions of human crisis and risk perception are inherently relational, much like the concepts of happiness or wellbeing, which vary widely across societies and contexts (cf. Douglas, 2002). This implies that ideas such as risk, danger, and vulnerability are neither universal nor value-neutral; they are deeply shaped by cultural, historical, and political influences.

In the context of contemporary Eastern African pastoral societies, relational and contextual approaches have been used to interpret cultural formations under conditions of conflict, displacement, and climate change (e.g., Konaka, et al., 2023; Semplici et al., 2024). Such approaches challenge non-dualistic and non-Eurocentric conceptions of “society” and “environment” (Castree, 2003), enabling a recognition of the multiple dimensions of reality and the dynamic, co-constitutive processes that shape the world. These ethnographies have revealed how local worldviews comprise intertwined moral, ecological, and spiritual dimensions, especially in relation to livestock. (Konaka et al., 2023: 8-9) also argued that relational ontologies not only “questions scientific epistemologies of knowledge” but also play a transitional role in moving beyond modernist, subject-centred perspectives. These works demonstrate how norms, values, belief systems, and causal reasoning are embedded in livestock-based ecologies, and how they contribute to localised understandings of wellbeing, morality, and environmental interdependence. However, what remains underexplored is how these entangled realms—cattle, divinities, environments, and human beings—co-produce notions of crisis and selfhood.

Rather than treating these entities as separate or static, this study emphasises their continuous and dynamic interrelation. Cattle, divine forces, and the environment do not stand outside human actors; they help constitute the self. To better understand this dimension, I propose that greater attention be given to the nexus of security of self in pastoral societies—an approach that illuminates how selfhood is formed, threatened, and sustained through relationships with nonhuman entities and cosmic forces.

In the Nuer thought, the self has never stood as an autonomous object of analysis. Instead, it has been described as embedded in a broader life force encompassing cattle (Evans-Pritchard, 1940), ancestors, kin (Evans-Pritchard, 1951), and divinity (Evans-Pritchard, 1956). Even amid change, the cattle-human equation did not collapse. Instead, a system of hybrid categories—linking cattle, monetary wealth, and forms of spiritual crisis—took shape and preserved the underlying equivalence (Hutchinson, 1996). Among the Nuer, the self has continued to be experienced as inseparable from others—an unending, continuous existence that transcends social transformations, even when the physical body as an individual has perished. In this sense, the notion of the self as discovered in Western modernity (cf. Foucault, 1984) appears ill-suited to describe the Nuer’s experiential world. Nevertheless, the global system—structured on the assumption of a modern self, institutionalized through modern education, development aid, and similar frameworks—has extended into African societies, at times generating friction and dysfunction.

Based on her 1980s fieldwork, Hutchinson showed that the principle of human–cattle equality endured through the circulation of blood and food—both treated as life-giving substances—and through the everyday practices and relational ties that sustained such circulation. The Nuer mode of selfhood observed within such relationships had undergone subtle changes. For instance, the increasing penetration of the monetary economy enabled individuals to purchase cattle—previously held collectively—suggesting a potential transformation in the conception of self, which had traditionally been embedded in relations with ancestors and divinity (Hutchinson, 1996: 98-99). How this form of selfhood has transformed and persisted in the context of renewed civil wars, climate change, and displacement requires investigation.

This study focuses particularly on situations in which human life and selfhood are placed under threat in contexts where cattle are absent. It contributes to studies of Nuer selfhood by showing how their continuous and relational conception of life—mediated through blood—persists in conditions of displacement and mobility.

The local concept of “blood” has attracted considerable attention as a source of life and life-giving power in Nilotic studies of Southern Sudan (Evans-Pritchard, 1956; Buxton, 1973), and as a force for forming alliances among people (Hutchinson, 1996). Especially in the context of social change, blood has linked individual experiences of homicide, death, and related moral crises during devastating armed conflicts to collective experiences through sacrificial practices (Hutchinson, 1998; Hutchinson, 2001; Hutchinson and Pendle, 2015; Pendle, 2018). Moreover, blood, or “bloodlessness” has been recognized as a force that regulates the power and authority of chiefs and spiritual leaders through sacrificial acts in modern civil wars (Leonardi, 2007; Pendle, 2023), as a criterion for the acceptance of monetary economies and political systems (Hutchinson, 1996; Leonardi, 2011), as a substance that creates kinship and ethnic identities (Jok and Hutchinson, 1999; Leonardi, 2007), and as a medium through which everyday understandings of life and death are formed (Hutchinson, 1996).

Existing studies on the relationship between blood and self have consistently approached it within a closed framework of circulation among humans, cattle, and blood, alongside associated substances, such as milk, semen, and food. This study seeks to move beyond this confined triad by exploring how blood relates to wider environmental and climatic phenomena—such as plants, rain, rivers, and the land—in constituting Nuer selfhood. Moreover, there are relatively few case studies examining the relationship between cattle and selfhood in diaspora, migrant, or refugee communities. After being separated from their land, does the formerly collective and relational self remain with them—and if so, how?

Methods

Study site and historical background

This study is based on long-term, multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork conducted between 2009 and 2018 in South Sudan and Uganda. The field sites included:

- -

Juba, the capital city of South Sudan, where research focused on displaced urban Nuer communities;

- -

Bor and Ayod in Jonglei State, flood-prone and conflict-affected regions inhabited by displaced pastoralists;

- -

Kampala, the capital of Uganda, where urban Nuer refugees and migrants have settled;

- -

Kiryandongo District in northern Uganda, where Nuer refugees reside in organised settlement camps.

As addressed here, the question of “who the Nuer are,” poses a considerable analytical challenge. As with many other African ethnic groups, the Nuer represent not only a historically and academically constructed category but also a continuous, lived process of identity formation—that is (re)negotiated by individuals through their experiences of civil war, displacement, and exile.

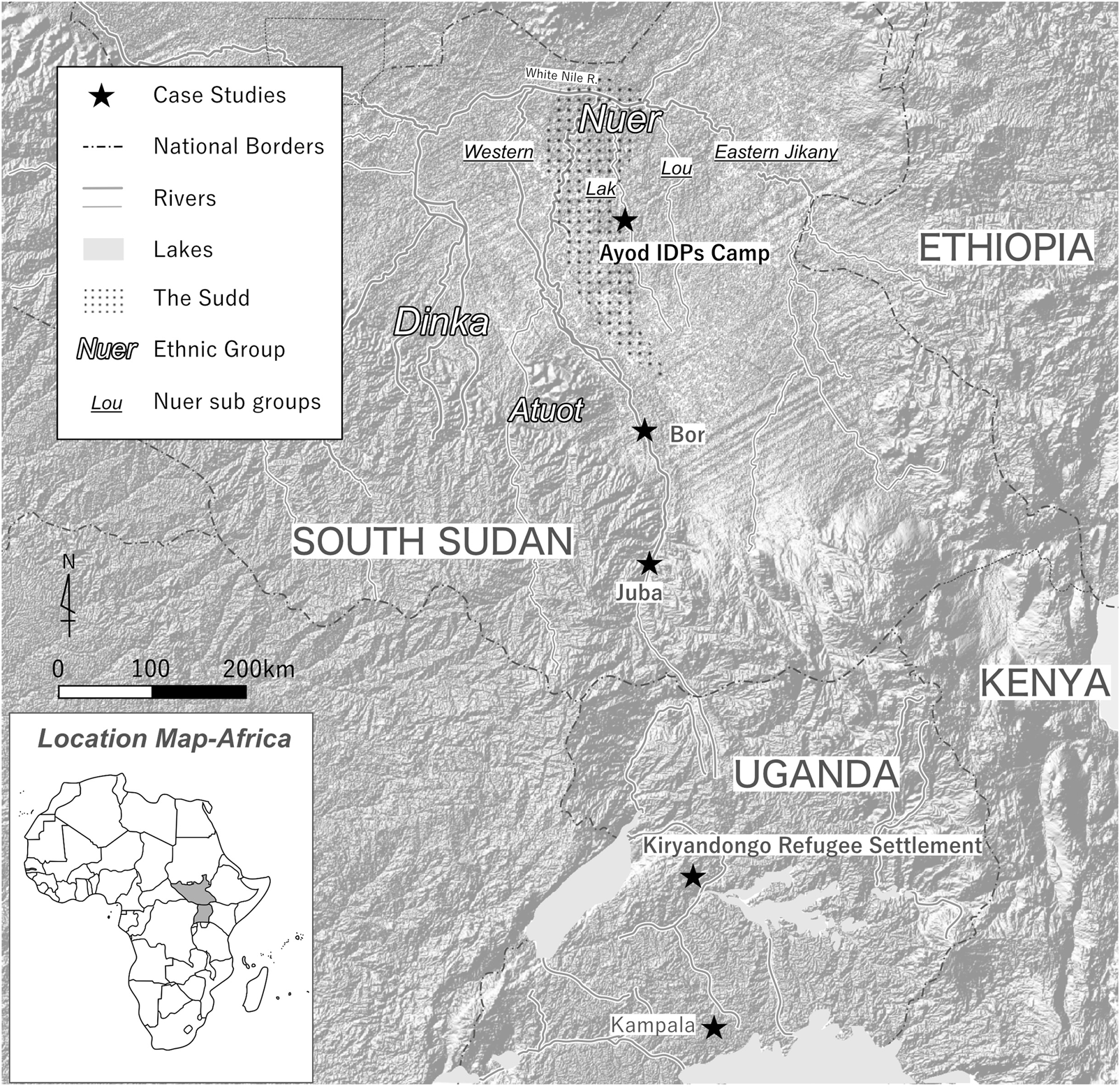

The Nuer are one of the culturally and linguistically diverse Western Nilotic groups whose communities have historically inhabited the flood-prone regions along the White Nile (see Figure 1), spanning from South Sudan to western Ethiopia. The Nuer sometimes refer to themselves as Naath (“the people”) or nei ti Naath (“the true people among the people”).

FIGURE 1

Map of the study area.

Earlier accounts often depicted Nuer society as internally cohesive and static—a view now challenged by scholars who highlight the community’s dynamic responses to broader historical processes such as colonial rule (Johnson, 1982a; Johnson, 1982b; Johnson, 1994), protracted civil conflict (Hutchinson, 1996; Jok and Hutchinson, 1999), displacement (Holtzman, 2000; Shandy, 2007; Grabska, 2014; Falge, 2015), the spread of monetary economies, the interaction between local divinities and Christianity (Hutchinson, 1996), and the shifting experiences of women and youth in these situations (Hutchinson, 1996; Falge, 2008; Grabska, 2014). Since the South Sudanese civil wars, attention has turned to how Nuer individuals from diverse backgrounds—such as political elites, village-based combatants, spiritual leaders, refugees, and migrants—have coped with uncertainty under conditions of national and ethnic violence (Hashimoto, 2013; Pendle, 2023).

Contemporary research rejects the idea of pastoralist tradition as static and instead shows how cattle-related idioms and values are continually reinterpreted and mobilized, even in diaspora settings, to negotiate identity, morality, and belonging. Despite regional and subgroup differences (e.g., among Western Nuer, Lou Nuer, Lak Nuer, and Eastern Jikany Nuer), many individuals continue to draw upon elements of ciɛŋ Nuerɛ2 (“the Nuer way of life”) as a flexible cultural repertoire shaped by both continuity and transformation.

Since South Sudan’s independence in 2011, the Nuer and other ethnic groups have endured severe inter-ethnic violence and national conflict. Concurrently, heavy and persistent rainfall has damaged rangelands, forcing many people to abandon both their homes and their cattle. Ayod, a region in Jonglei State, was among the areas most affected by both flooding and armed conflict, and it became a hub for internally displaced persons (IDPs) (IOM South Sudan, 2013). Similarly, large numbers of IDPs and migrants also resettled in Bor and Juba, the capitals of Jonglei State and South Sudan, respectively.

Following the outbreak of civil war in late 2013, humanitarian concerns intensified regarding the compounded effects of flooding and conflict on displacement and the feasibility of return for refugees and IDPs (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2014). Although climate change and flooding only began to gain significant attention in South Sudanese policy discourse around 2019, severe flooding had already been a major issue during the earlier conflict years. During my fieldwork, many displaced individuals reported that flooding—not only conflict—was a primary reason they could not return to their ancestral villages. In this context, flooding operates not only as an initial cause of displacement, but also as an enduring barrier to return and recovery.

Data collection and analysis

In South Sudan, data collection was carried out between 2009 and 2013 through a combination of homestays in private households in Bor and Juba, and accommodation in NGO guesthouses and other facilities in Ayod. In Uganda, fieldwork included visits to Nuer migrants and refugees in Kampala while staying at the university guesthouse at Makerere University. In the Kiryandongo Refugee Settlement, research was conducted through homestays in private residences and hostels.

During the fieldwork, my research did not focus on a “climate narrative” per se, but rather on Nuer historical consciousness expressed through local prophecies in South Sudan and on cultural practices among refugees and migrants in Uganda. In this paper, I highlight relevant narratives and practices and reposition them as part of the broader debate on “climate narratives,” in a way that deepens the discussion of Nuer relational selfhood.

The methodology combined participant observation, ritual documentation, and semi-structured interviews with a range of informants, including elders, youth, and ritual specialists. Participants were recruited using snowball sampling, beginning with my host family in South Sudan, who held positions as both religious and community leaders. In Uganda, participants were recruited through snowball sampling, beginning with community leaders I met at refugee settlements and in cafés in Kampala, where Nuer people were known to gather.

The number of interview collaborators directly relevant to this study (including those with whom I engaged in extended everyday conversations) was approximately 30 in South Sudan—comprising men and women across a wide range of generations—20 in Kiryandongo, Uganda, primarily religious specialists and young male and female refugee leaders, and 10–15 in Kampala, consisting mainly of educated young migrants. When instances of participant observation are included, the number of research collaborators is considerably higher. Most of the interviewees cited here are men. Although about ten women also participated, I was unable to collect sufficient data from them, which remains a task for future research. Interview data were documented through detailed notetaking rather than audio recordings.

Interviews were conducted primarily in English and Nuer, with the assistance of a Nuer–Juba Arabic bilingual interpreter in cases where informants, particularly elderly individuals, did not speak English. Additionally, the study incorporated historical perspectives through analysis of previous ethnographies to trace transformations in the meanings of cattle, climate, and divinity over time. The main informants were Nuer IDPs and refugees, many of whom were former pastoralists. Some had become educated urban migrants who did not intend to return to their villages or former pastoral livelihoods. In towns like Juba and Kampala, informants included Nuer Community Leaders (NCL)3 and church leaders, who played key roles in maintaining mutual support networks among displaced Nuer populations. Similar community leadership structures were also observed in the Ayod IDP camp and in refugee settlements in Kiryandongo. Other important informants were ritual specialists, who continued to perform sacrifices and religious practices not only in villages but also in towns and refugee settings.

The Uganda fieldwork focused particularly on refugees displaced by the widespread armed conflict that began in late 2013. Although most of these individuals were displaced by political violence that has since subsided, their return to South Sudan has become increasingly unfeasible owing to ongoing instability and climate-related impacts, including flooding and deteriorating rangelands.

Since I conducted multi-sited fieldwork, my positionality as a researcher varied significantly across sites. In Bor and Juba, I lived with a local host family and was given a local name—a gesture symbolizing social acceptance and community integration. By contrast, in the Ayod IDP camp and Uganda, I mainly stayed in guesthouses, which provided a degree of proximity to everyday life but also reinforced my outsider status. This shift from relatively distant observer to more embedded participant enabled deeper ethnographic insight and shaped the ways in which interlocutors engaged with me. These variations in field relationships were reflexively examined in the analysis, particularly regarding how trust, access, and meaning were constructed in each context.

Alongside thematic analysis and historical comparison, data interpretation was informed by ethnographic methods and practice theory. A comparative ethnographic approach was also employed to explore how individuals in different socio-cultural contexts reproduce or challenge normative structures through their everyday practices.

To shed light on observations from my field research, I also referred to secondary sources, including Nilotic ethnographies related to rituals and notions of divinities (e.g., Lienhardt, 1961). Furthermore, to enrich comparison between Nuer relational selfhood and modern European thought on selfhood and its connection to climatization, I drew on UN reports on climate change and flooding in South Sudan to identify features of the predominant global climate discourse. Finally, to analyse the contrast between different modes of selfhood, I engaged with Malkki (1992), Malkki (1995) discussion on sedentalist/nationalist modes of self and identities.

Notably, the people at the centre of this study did not migrate explicitly because of climate change, nor do they frequently articulate their experiences in terms of “climate” per se. From this perspective, it becomes meaningful to interpret how displaced Nuer people living in climatised realities understand their crises, selfhood, and relationships to the environment through what may be called a climate narrative, as I discuss later.

Results

Kuɔth, cattle, and blood among the Nuer

In 2010, prior to South Sudan gaining independence, an educated Nuer migrant living in Juba shared the following reflection on kuɔth:

Kuɔth becomes the wind and arrives. It then becomes air and enters our bodies as breath. Again, it leaves our bodies as breath and turns once more into wind. In this way, kuɔth is present in everything. Kuɔth is one, yet it has many colours. We cannot choose those colours. Since we would die without air, this life itself is a gift from kuɔth. The presence of kuɔth within us is evident in the fact that we are alive (Interview with a 30–40-year-old educated Western Nuer man; Juba, July 12, 2010).

This perspective on the ubiquity of kuɔth was already documented in ethnographic accounts from the 1930s (during the British colonial period; Evans-Pritchard, 1956: 1–2). Among the Nuer, kuɔth is not only present in visible phenomena but also in invisible ones such as wind, air, and breath. It is described as being “everywhere,” like the wind. Kuɔth is commonly understood in two forms: kuɔth nhial (kuɔth of the sky) and kuɔth piny (kuɔth of the earth). The word kuɔth captures both the intangible nature of air and the action of exhaling; in its verbal form, it can describe actions such as blowing on fire embers (Evans-Pritchard, 1956: 1). Nhial means “sky” and is associated with natural phenomena such as rain, thunder, and birds. Kuɔth manifests in the sun, moon, rain, and wind. Thus, environmental changes are perceived as messages from kuɔth.

Cattle play a central role in shaping Nuer selfhood and mediating the relationship between humans and kuɔth. As in other Eastern African pastoral societies, cattle are deeply tied to identity, social relations, and religiosity. Cattle are used as bridewealth, compensation, tokens of friendship, and as sacrificial offerings to communicate with kuɔth. When the relationship between humans and kuɔth is destabilised—which often manifests as anxiety or a sense of threat—sacrifices are performed to restore balance. Cattle thus serve as indispensable media for asking for peace, protection, and continuity. Most Nuer today identify as Christians, though belief in local prophets persists, especially during times of armed conflict (Hashimoto, 2013; Hashimoto, 2017; Pendle, 2020a; Pendle, 2020b). In Christian discourse, kuɔth is also used to refer to the Christian God. During the Second Sudanese Civil War (c. 1983–2005), Christianity spread widely in Nuerland. This provoked tensions around traditional practices such as animal sacrifice. Despite Christian prohibitions, sacrifices continued to be practiced in cases of moral and spiritual crisis—such as murder, injury, or violations of incest taboos, which were believed to require ritual resolution (Hutchinson, 1985; Hutchinson, 1996: 299-350).

To this day, sacrificial rituals are typically performed by religious specialists or respected elders. One such figure is the earth priest (kuaar muon), who is believed to possess ritual power through his association with the land (mun, muon), including the ability to bless or curse (Evans-Pritchard, 1940: 262) Although their political authority declined with the advent of government and police during the colonial period (Johnson, 1986; Johnson, 1994), they continued to play a role in dealing with spiritual pollution.

Among the Nuer, sacrifice has long been performed at various life transitions and moments of crisis. In particular, the offering of cattle in purification rites associated with blood pollution has been accorded enduring importance because such rites are profoundly endanger the lives of both victims and perpetrators, as well as their kin and descendants.

Nueer refers to a form of blood pollution resulting from intra-Nuer killing, where one Nuer takes the life of another. Because the victim’s blood is to enter and mix within the perpetrator’s body, the killer is forbidden to eat or drink until this foreign blood has been expelled through the intervention of a kuaar muon (Evans-Pritchard, 1940: 235). Immediately after committing a killing, the perpetrator flees to the house of the kuaar muon, who makes an incision, known as bier, on the killer’s arm. As blood flows from this cut, the dangerous intrusion of the victim’s blood is thought to be averted. The kuaar muon then performs a sacrificial rite with the livestock provided by the perpetrator. This sacrifice must be carried out not only on behalf of the killer but also for the purification of his kin and the wider village community from the pollution of the victim’s blood (Evans-Pritchard, 1940: 237). If it is not performed, the perpetrator and his community are believed to be exposed to illness and a range of other misfortunes.

During the second Sudanese civil war, the traditional concept of nueer was destabilized amid the increasing circulation of firearms and the unprecedented scale of Nuer-on-Nuer killing within national conflicts. In the 1980s, leaders of the SPLA (Sudan People’s Liberation Army) sought to alleviate people’s anxieties by asserting that killings committed in the context of the national struggle did not generate nueer (Hutchinson, 1996: 106-108). In the civil war that erupted in South Sudan at the end of 2013, local prophets and soldiers rediscovered and reworked the notion of nueer in the context of national-level conflict; they argued for the necessity of removing such pollution as part of efforts toward conflict resolution and peacebuilding (Pendle, 2023). As later cases will illustrate, however, in the everyday lives of migrants and refugee, the possibility that homicide (or attempted homicide) might produce nueer continued to be regarded as a serious concern.

Rual denotes a type of blood-related pollution that is implicated in acts of incest. Incest is regarded as a grave sin that brings death, and this understanding has been maintained even amidst social change. Although Nuer definitions of incest have always been extensive, they have also changed over time. In the 1930s, Evans-Pritchard noted that the gravest forms of incest involved maternal kin and that exogamy extended over wide agnatic and cognatic distances (Evans-Pritchard, 1951). By the 1980s, however—especially among Eastern Nuer—these limits had contracted, several prohibitions had relaxed, and incest with a father’s sister’s daughter had come to be viewed as the most dangerous and fatal category (Hutchinson, 1992b).

When people suspect a case of rual usually signalled by illness or misfortune—and judge it to be mild, they first attempt to heal it with medicine. Next, plants such as cucumbers or the sausage tree (the latter being relatively common in Western Nuer) may be used. If the rual is judged to be severe and involves a very close kinship, a sacrificial offering of a sheep or goat is required, and in the most serious cases, a cow must be sacrificed. In such cases, the kuaar muon ritual must be performed immediately. During the sacrifice, the animal is slaughtered by being cut vertically in half, and afterwards, the person who committed the offense must drink medicine infused in the gall of the sacrificial animal. This ritual is called bak, meaning “dividing one thing into two.”

Although this study did not confirm any concrete changes in the definition of incest, even young people and children living in urban areas understood the dangers of rual, and practices such as recalling and identifying the names of ancestors were still being carried out (Hashimoto, 2018). Thus, rual remains a matter of concern even after leaving the land.

In this manner, Nuer life continues to be sustained by kuɔth and blood-purifying activities. However, selfhood and its security are also identified and sustained through the ownership, exchange, and ritual use of cattle, which are essential for social reproduction and future generations.

Value of cattle among Nuer migrants and refugees

Despite historical transformations like colonisation, civil war, the spread of Christianity, and modern education, cattle have remained conceptually and practically significant in Nuer life. In the 1980s, for example, debates arose over substituting cash for cattle in bridewealth payments, challenging long-held cosmological and moral understandings (Hutchinson, 1996: 56-102). When the cash economy first reached Nuerland, the attribution of bloodlessness was provided to cast doubt on the reliability of cash (Hutchinson, 1996: 74). Although cash is often used in bridewealth transactions in refugee and migrant communities in Uganda, marriage without cattle is still considered ominous, and is thought to potentially result in infertility or misfortune. Several informants explained that “marriage by cash has no blood,” making it morally problematic: “Marriage without cattle is like incest;” “To be a wife, there must be blood—the blood that flows when cattle are killed” (Interviews with refugee Western Nuer men aged around 30–50 years old, who were chatting in a cafe in the Kiryandongo refugee settlement; 1 March 2018).

At a marriage ceremony I observed in Kampala among Nuer refugees, participants negotiated bridewealth payments by referring to dollars as cattle. Demonstrating the equivalence of cash into cattle, bundles of money were counted as one, two, or three cows (Hashimoto, 2018). The moral logic remained: even when using money, it must be recognised as a cow. This reflects the belief that the “blood” of the cattle is what ensures the legitimacy and spiritual protection of the marriage and its descendants.

As part of modernisation, various exchange media have emerged to replace cattle. Yet, their value is still judged by how well they replicate the spiritual and moral properties of cattle, especially through the concept of blood. Another critical concept is that of “not finishing” (kanɛ thɔak), which contrasts cattle and education with cash.

In 2013, at an IDP camp in Ayod, a Nuer man who had lost over 60 cattle described his plans as follows:

If I return to the village and acquire a cow, [I] do not convert it into cash; [I] keep it. Cows produce offspring, so the cycle does not finish (kanɛ thɔak). Cash, however, finishes (thɔak) the moment you buy something. But if it’s for your children’s education, you may convert the cow into cash. With an education, your children can secure good jobs, earn cash, and use it to raise cows (Interview with a Lou Nuer man, about 50 years old; Ayod, January 16, 2013).

This reflects a cyclical logic of value rooted in continuity and intergenerational transmission. For the Nuer, “not finishing”—something that is manifested through cattle—is an essential moral and cosmological principle; it also applies to mistakes. This perspective explains why this man identified a similarity between cattle and education. Errors or moral failings are not considered to “finish” with the individual, but are carried forward to descendants, unless ritually resolved.

Therefore, to avoid intergenerational misfortune, sacrifices are performed—even in displacement, refugee settlements, or urban environments—using available substitutes. These practices show how Nuer relational and collective selfhood adapts to new environments while retaining its core logic.

Remote sacrifice and sacrificial substitutions

Remote sacrifice

Among the Nuer, most sacrifices serve a particular purpose; that is, they are intended to remove impurity and restore spiritual and social balance by communicating with kuɔth. Sacrifices are typically performed in moments of crisis, such as disaster, murder, injury, illness, initiation, or the violation of incest taboos, when individuals or communities face life-threatening situations.

But what happens in an era of cattle loss? When people no longer have cattle readily available, their first response is often to search for real cattle, even remotely. What I refer to as “remote sacrifice” involves the ritual being performed in a rural village, on behalf of urban or displaced family members, while the same moral obligations and ritual norms are shared across geographic distances.

Case study 1: remote sacrifice following attempted murder

C, a Lou Nuer priest of the “Ngundeng Church” in Bor and around 40 years old, regularly performs cattle and goat sacrifices as part of his ministry. “Ngundeng Church” is a place for prayer for those who believe in a local prophet; it was established among refugees in Ethiopia in late 1990s (Falge, 2008). While I was staying at his home in Bor, a shooting incident occurred in his extended family’s rural village. C was immediately contacted via mobile phone and informed that a ritual taboo had been activated.

After a sacrificial ritual using cattle was performed in the village, the taboo was considered lifted, and family interactions could resume. C explained that in cases of blood impurity, including injuries or killings, no Nuer, whether in a rural village or city, is exempt from the spiritual and social consequences. The impurity must be ritually addressed, typically through the sacrifice of cattle, regardless of the location of the affected individuals. During an interview in January 2012, he outlined the procedure as follows:

The affected individuals consult a member of the earth-priest lineage nearby.

The incident is communicated to relatives across locations—village, urban centre, or refugee camp—and it is publicly acknowledged that “blood lies between” the two families.

The earth priest or their kin advises what type of sacrificial animal (cow or goat, of a specific colour/pattern) should be used.

The sacrifice is carried out in the village, and the meat is shared among both families.

Through the ritual, it is declared that “the wound has been washed away” (buot puor), and the taboo is lifted for those living even in distant places.

This case demonstrates how moral transgressions (duor) and blood impurity are not confined to individuals or locations but extend across kin networks. If not ritually resolved, the consequences may pass on to future generations. Therefore, the safety of selfhood is not solely an individual concern, but a collective responsibility. This illustrates a distinctly relational model of selfhood, in which the moral and spiritual conditions of one’s relatives, ancestors, and descendants are intimately connected.

Sacrifices of limes: substitutes for cattle

When cattle are unavailable even in rural areas, the Nuer turn to substitute materials. One classic example is the use of wild cucumbers (Cucumis prophetarum), referred to as “bull cucumbers” (kuol yang), particularly for minor anxieties such as nightmares (Evans-Pritchard, 1956: 203).

In the traditional bak ritual, used to purify incest taboos (rual), a cow is literally cut in half from head to tail―“splitting one into two” as they put it. Rual is said to be a state in which “blood is one,” requiring division through sacrifice (Interview with a male Eastern Jikany Nuer refugee, aged in his 20s or 30s; Kampala, August 26, 2016). If cattle are unavailable, wild cucumbers are used. The cucumber is consecrated, split with a spear, and one half is discarded while the juice from the other half is sprinkled, drunk, or applied to the body.

However, in Uganda, where both cattle and wild cucumbers are scarce, Nuer refugees have turned to limes as a substitute. The following two cases illustrate this adaptation.

Case study 2: resolving Rual in Kiryandongo and Juba

In 2013, in the Kiryandongo refugee settlement, a man’s children became ill. Sensing something was spiritually wrong, he consulted J, a member of the earth priest lineage from the Western Nuer in his 50s or 60s. J investigated the man’s recent history and suspected that a sexual relationship with a Ugandan woman including oral sex, deemed morally inappropriate, could have activated rual.

The man purchased a goat and a lime. J performed the ritual by cutting the lime in half, discarding one half and squeezing juice from the other half, which was then given to the man’s wife with the incantation: “Rual will be split, rual will go, and you will return.” This case shows an expanded interpretation of rual going beyond incest among kin to include a different act seen as morally ambiguous or socially destabilising. Mirroring the ritual structure used with cucumbers or cattle, the lime replaces the cucumber, which itself once replaced the cow.

In 2017, in Juba, a woman fell ill following the death of her husband. She reported that a bad spirit (yiey mi jiɛk) was still “following her.” Though the exact cause was unclear, J suspected a problem of blood and performed a precautionary bak ritual using a lime. As in the case of 2013, he split the lime, discarded one half, and gave the juice of the other half to the woman.

These two cases are based on J’s account, and it might be assumed that they are methods unique to J or J’s family. The extent to which this method is popular or widespread should be further investigated. However, I repeatedly asked other refugees about this lime offering, and many stated that such a practice is indeed possible.

As Evans-Pritchard (1956: 146, 197) noted about similar practices, one half of the fruit symbolises the dead or impure part and is thrown away; the other represents life, children, and the continuing self, and is placed in the home or ingested. When asked, “Why limes?,” the ritual specialist explained: “A lime is like a wild cucumber, and a wild cucumber is like cattle … Just one thing: we never use dried limes or cucumbers” (Interview with J in Kiryandongo; 1 March 2018).

This statement reveals a form of ontological relationality in which juice is equated with blood, and the presence of freshness ensures that the offering is both vital and spiritually efficacious. A dried lime is unusable, just as a dead cow cannot be sacrificed.

Ultimately, these examples demonstrate that Nuer sacrificial practices are flexible yet grounded in deep principles of blood. Whether using cattle, cucumbers, or limes, what matters is the ritual form, the intent to divide impurity, and the preservation of relational selfhood across generations and geographies.

Discussion

Nuer collective and relational selfhood

As numerous ethnographic studies have demonstrated, the Nuer selfhood concept remains inseparable from kuɔth and cattle, even after significant cultural transformations owing to displacement, armed conflict, and current climate change. Newly emerged sacrificial practices show that ancestors’ sins and mistakes are considered to follow the living, wherever they are. In response to misfortunes understood as forms of blood pollution, Nuer individuals and communities carry out sacrificial rites with cattle, or, when necessary, with substitutes such as cash, cucumbers, or limes—items recognized as bearing or standing in for blood. These rituals ensure secure collective wellbeing and that their lives remain “not finished.” In previous studies of sacrificial practices, emphasis has been placed on cattle–human equality, with blood understood as a substance whose circulation guarantees selfhood’s continuity. Indeed, as Case 1 illustrates, even in an era of displacement, communities continue to mobilize their available social resources to perform cattle sacrifice as a means of resolving crises. The inseparable relationship between humans and cattle thus remains an indispensable element in constituting Nuer selfhood. As Case 2 demonstrates, however, even when cattle are absent, people attempt to locate alternative sources of blood so that their extended, relational life—including that of their kin and descendants—does not “finish,” as they put it.

These practices reflect a relational, distributed, and hybrid selfhood, in which the individual is never fully autonomous but always embedded in a network of others, including ancestors and descendants. This collective selfhood is not merely symbolic; it has material and moral consequences, shaping how people manage crisis and security across time and space. A key question remains: How do the Nuer attempt to control and stabilise this collective selfhood? An important part of the answer lies in the fluidity of blood, a concept that emerges clearly through the substitution of cattle with limes and cucumbers in sacrificial rituals.

While previous studies have demonstrated that Nuer selfhood is constituted through an intimate unity with cattle and, more fundamentally, through the circulation of blood and food that binds humans and cattle together, the range of objects that can be encompassed within the category of riɛm has since undergone significant transformation. It is noted that blood was associated with life-sustaining substances such as cow’s milk, breast milk, and semen (Hutchinson, 1980; Hutchinson, 1992a: 303, Hutchinson, 1992b: 493-494, Hutchinson, 1996:173, 178-179). However, in contexts of displacement and cultural transformation, the domain of what may be regarded as riɛm has expanded. This includes the new relationship between cattle and money brought about by changes in the monetary economy and the labour market (Hutchinson, 1992a), the increasing association of “sweat” with riɛm in the rise of wage labour and agricultural work (Hutchinson, 1992a: 303, 314, 1992b: 494), and the emergence during the civil war of simplified purification rites using “water” in cases of gun-related killings (Hutchinson, 1996:142-143, 2000: 63-70; Pendle, 2023: 235). These developments indicate the need for further examination of blood and the various phenomena linked to its fluid and expansive qualities.

Fluidity of blood and sustainable selfhood

To fully grasp the logic behind sacrificial substitutions, it is helpful to draw comparisons with other Nilotic societies. That entities other than cattle may contain or embody “blood” has, in fact, already been noted in several classic studies of these societies. Wild cucumber and the fruit of sausage trees were reported as substitute media for cattle sacrifice among Nilotic people (Lienhardt, 1961; Burton, 1981; Burton, 1982). However, the reason why these fruits can be used as an alternative for cattle has never been clearly analysed. A close reading of these descriptions reveals that the sacrifice of cucumbers or the sausage tree fruit involves more than simply substituting for cattle. Rather, such practices highlight their significant associations with fluid environmental and meteorological phenomena essential to Nuer life, such as rain and rainmaking, or rivers that are at times spoken of as givers of life.

Among the Dinka, the cucumber sacrifice is performed to protect against sickness and withdrawing curses that take fish away from the river. This ritual is also associated with people called spear masters, who are rainmakers and controllers of the river, and thereby recognised as life-givers. In the ritual, the cucumber is cut in half and placed into a gourd of water, which floats on the river (Lienhardt, 1961: 225). In this ritual, connectivity among river, rain, and the water the cucumber contains, as different forms of liquid, can be used to sustain their lives.

For the Atuot, the neighbours of the Dinka and Nuer (Figure 1), a cucumber is also associated with the power of rain. When there is no rain, a wild cucumber is sacrificed with other animals and materials. Women dance and sing, “God let the water pour down.” This is a prayer for divinity associated with rain that is called kwoth. A cucumber contains a soft, fleshy, moist substance that is associated with women or fertility (Burton, 1982: 74) and referred to as “moving blood” or the “life-giving power of rains” (Burton, 1981: 88–90).

As described above, among the Nuer, riɛm is central to the evaluation of risk and life itself. It is paradoxically described as both vulnerable (the “weak” and “cold” part of a human being), and simultaneously the source of human wellbeing, order, and power, embodying health, fertility, and harmony. Blood is something passed down from person to person, signifying respect for older generations. Belonging to and expanding the kinship group—including ancestors—is conceptualised through the term creation and movement of blood, whereas the dissolution of families is represented as blood loss (Hutchinson, 1996: 75-76). Vulnerability is defined through the status of blood, whether it exists or not, is one or has been split. To overcome this vulnerability and avoid “finishing of life,” it is said that the blood should be kept “cool” (koc) and made strong (buom). “Coolness” shows the “fertility of women,” related to capacity to reproduce. For example, when a girl experiences her first menstruation, she is said to have “become cool” (Hutchinson, 1996: 77). Hence, cattle with blood in their bodies were used to control blood impurities. Additionally, the “hotness” of the ground and “coolness” of liquid maintain a mutually influential relationship that sustains Nuer life and helps avoid misfortune. Rain is a life-giver, just as a person who performs a ritual makes the “hot” ground “cool.” Blood’s coolness grants women fertility, and thereby, a self-continuity. Just as rain cools the earth to ensure its fecundity, so too does blood—fluid, ever-changing in form, and continuously cooled—overcome the fundamental vulnerability of human beings, anchoring the relational self to the world. These examples illustrate a network of lives connecting cucumber juice, rain, rivers, and human blood. This implies that controlling liquids recognised as shared “blood” is to act upon the nexus of selfhood, which is constituted by rivers, rain, the life-giving power of women, and blood, with all of them characterised as liquids. In this network of liquids, cattle blood, cucumber juice, and lime juice are ritually equivalent: each serves as a fluid medium to address spiritual impurity and reinforce the continuity of the self across generations. These fluids are seen not only as symbols, but as active agents that secure life, fertility, and the collective self. In that sense, the self is single but manifold, ubiquitous, always invaded by the world and, thus, flowing everywhere. Shedding “blood” in place of a human being in a sacrifice provides a temporary guarantee of security for the human individual and community.

Selfhood of “blood” vs. “soil”

How do these features of selfhood differ from the forms of selfhood assumed in post-industrial Europe, the neoliberal world, and nation-states? How can we define Nuer collective selfhood as one among many “climate narratives”?

The Nuer’s notion of a fluid, relational, and distributed self stands in sharp contrast to the individualised, bounded self imagined in industrial modern European, neoliberal, and climatised models of vulnerability. In such paradigms, nature is treated as an ideological tool, and identity is often rooted in metaphors of land and soil.

Malkki (1992) pointed out that “soil” is a key part of sedentarist metaphysics, in which it is synonymous with terms such as “land (homeland),” “nation,” and “countries” (26). The term “soil is like “native,” “indigenous,” and “autochthonous” have served to root culture,” that also derive from the Latin term for cultivation (Malkki, 1992: 29).

In the context of climate change in South Sudan, a tendency exists to associate “soil” with specific human groups as a way of framing the crisis. For example, the UNICEF Deputy Executive Director argued that “empowering women and strengthening communities is essential for climate adaptation” [United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women), 2021: 3]. The report further insists that “there is a strong link between climate change and gender issues in all societies, particularly in developing countries like Sudan”, asserting that “climate change is expected to reduce crop yields, where women are the main victims” [United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women), 2021: 20–21, 27].

However, framing women’s vulnerability solely in terms of agricultural labour positions them as passive victims of environmental change. This perspective ignores the complex and collective livelihood strategies practised within extended families and kin networks. Such framings are rooted in a neoliberal subjectivity that individualises poverty, reducing it to a personal deficiency, and in a settlement-centred worldview that presumes an intrinsic link between people, land, and cultivation. These assumptions oversimplify both the causes and lived experiences of crises. Of course, the question of how people might perceive a crisis and how they might respond to it—their perceptions and practices—is not at issue.

This metaphysics and imagined “order” and “ordinality” create images that imply that one who has roots and soil is normal, while those who are “uprooted” and “displaced” are vulnerable and must be helped. Malkki called it one of the devices by which the “national order of things” (Malkki, 1992) can be shaped and one’s identity territorialised.

Latour (2017) also indicated that ground/soil has been shaped as “territory” since the birth of the modern nation-state, which serves as the main way in which we are connected to certain soil/ground. Yet, the notions of “soil”, “ground”, and “land” are changing given the increase in migration and climate change, and our troubles and anxiety are related to the vulnerability of our “ground” on which we stand. As Malkki (1995) wrote, “The territorializing metaphors of identity—root, soil, trees, seeds—are washed away in human floodtides, waves, flows, streams, and rivers. These liquid names for the uprooted reflect the sedentarist bias in dominant modes of imagining homes and homelands” (15–16).

Grounded in fluidity and expressed through “liquid names”, Nuer relational selfhood offers a potent counter-narrative to modernist, nationalist, and climate-driven discourses built on “territorialising metaphors”. The fluid qualities of cucumber juice, lime juice, and sacrificial blood enable people to meet crisis, preserve continuity, and sustain relational safety even during displacement. This can thus be posited as a local “climate narrative” that shows how people create alternative forms of stabilising and life-making in the world where “ground” and “soil” are no more guaranteed.

Toward living with uncertainty

Relational ontologies raise question about worldmaking—how we imagine the world and how we fail to govern it. In South Sudan, both scarcity discourse and the climatic lens have functioned to recast events such as conflict and displacement as climate problems. The Government of South Sudan’s Initial National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention (Government of South Sudan, 2018) repeatedly emphasizes the country’s high climate vulnerability and lack of adaptive capacity. Adaptive capacity is defined as “the ability of a system to adjust to climate change to moderate potential” (Government of South Sudan, 2018: 160) and is described as shaped by factors such as socioeconomic conditions, population dynamics, women’s education, food insecurity, and poverty, among others.

This climatisation process serves specific global actors, transforming “nature” and “climate” into ideological constructs that justify environmental control and policy interventions. Within this climatised framework, human beings are often portrayed as passive entities, continuously shaped by natural forces. Individuals and communities are defined through their relationship to land and agricultural production, with little acknowledgment of their agency or cultural logics. Such assumptions not only obscure local subjectivities and adaptive strategies but also fail to account for the complex interplay of environmental, social, and political factors that shape both crisis and vulnerability.

If these assumed social factors derive from instabilities brought about by global discourses and development aid, could the Nuer’s relational understanding of the self through blood—which does not align neatly with global frameworks of human–nature relations—be considered a form of adaptive capacity? In societies such as South Sudan, where multiple layers of uncertainty prevail, it is crucial to design projects and policies not to eliminate uncertainty but to “live with” uncertainties (Scoones, 2023), drawing on local modes of thought. In this regard, the Nuer’s relational understanding of the world and self-making proves valuable.

As demonstrated in the relational ontologies surrounding blood among the Nuer, incorporating uncertainty related to natural phenomena or displacement as part of the self is more persuasive to local people than the Euro-modern approaches that objectify nature as separate from the self. This perspective also has potential applications in environmental education and related fields (cf. Riley et al., 2024).

Future perspectives and study limitations

In this article, I have examined the continuity and transformation of relational selfhood as observed through emerging forms of sacrifice. Looking ahead, as access to cattle becomes increasingly difficult, the significance of plants as “sacrificial beings” that can contain or embody “blood” is likely to grow further. These developments point to the need to reconsider how ideas of the self are changing in response to the expanding monetary economy and the altered conditions of cattle ownership.

Through multi-sited fieldwork, this study shows that Nuer people, despite diverse experiences of displacement, retain a shared understanding of “blood” and cattle and the forms of relational selfhood tied to them. However, because this study relied primarily on interviews and conversation with elders, leaders, and ritual specialists, the perspectives of women, youth, and less ritually engaged individuals may be underrepresented. Further research should include participants from more diverse backgrounds to explore how these modes of worldmaking may vary according to personal attributes and how they may nevertheless be shared.

Further comparative inquiries into ritual substitutions across pastoralist societies are also necessary. Such studies could contribute to an anthropology capable of both critiquing facile scientification and engaging in more reciprocal modes of worlding.

Conclusion

This article has examined how consistency of the Nuer’s relational selfhood and perception of crisis is maintained through practices involving cattle or their substitutes. As highlighted in discourses on climate change in South Sudan, climate crisis-related risks and vulnerability are often linked to forced migration. The image of the human subject that underpins this perceived vulnerability is that of a passive recipient, constantly affected by the environment. Such portrayals tend to overemphasise individual attributes such as gender or age as inherent sources of weakness. They thus constitute an excessively “individualised” representation rooted in the notion of an autonomous, independent self that is tied to specific “soil” or “ground.”

By overcoming the “vulnerability of blood,” the Nuer people ensure that their lives are safeguarded against misfortune. Blood, as kuɔth, flows everywhere within a given context. Blood’s fluid character thus offers the possibility of a “sustainable self” that transcends region and generation in times of crisis. In these contexts, I have shown that “blood” destabilises the presumed priority of humans and the rigid boundaries separating humans, animals, artifacts, and plants. This transgression of ontological limits enhances the status of the self. By responding to vulnerable blood with other forms of “blood”, the Nuer people reveal inseparable human–world–animal relationships and vernacular modes of “risk management”. We learn how they manage their “troubled selves” and fashion a “sustainable self” through the process of multiple liquids constantly flowing in and out of bodies.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies were conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. In South Sudan, the Ministry of Higher Education and local authorities approved the research for this paper. In Uganda, approval was granted by the Office of Prime Minister and the Media Council. Written informed consent for participation was not required, as participants offered verbal consent; consent from legal guardians and next of kin was also not required under these circumstances.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was supported in part by JSPS Kakenhi (Grant Numbers: 23H00031, 23K12347, and 18K12601).

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the Office of the Prime Minister in Uganda for their permission to conduct research in the refugee settlements, and to Peace Winds Japan for their support during my fieldwork in the Ayod IDP camp. I also thank Prof. Shinya Konaka for his invaluable guidance and comments. My heartfelt gratitude goes to all research participants in Uganda and South Sudan. Finally, I wish to acknowledge my research assistants and host families—James, Chudier, Chaar, and Nibol—for their generosity, trust, and care.

Conflict of interest

The authors(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Artificial intelligence tools were used solely to check the English grammar and wording of the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Footnotes

1.^Although many discussions exist regarding the definition and meaning of “ontology” in the field of anthropology (e.g., Carrithers et al., 2010), this article adopts an ontological perspective based on the relational ontology proposed by Konaka et al. (2023). This is because my discussion places greater emphasis on what can be discovered through the concept than on what the concept defines.

2.^The term ciɛŋ essentially means “home” in the Nuer language. However, its meaning is context-dependent; it can mean family members or be used as the name for one’s hometown or homeland. When referring to the way the Nuer do something to achieve the ideal Nuer life, it may be translated as “culture”.

3.^NCL is a mutual aid organisation for the Nuer people living in various regions, with interconnected branches in the United States, Canada, Australia, Egypt, and Sudan. This organisation’s positions, including leadership roles, are established according to regional Nuer groups and their subgroups; it functions as a mechanism to maintain the Nuer community’s sense of solidarity.

References

1

BrownK. S. (1999). Taking global warming to the people. Science283, 1440–1441. 10.1126/science.283.5407.1440

2

BrüggemannM. (2020). Global warming in local discourses: how communities around the world make sense of climate change (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers).

3

BurtonJ. W. (1981). God”s ants: a study of Atuot religion. St. Augustin: Anthropos Institute.

4

BurtonJ. W. (1982). Atuot ethnicity: an aspect of Nilotic ethnology. Africa51 (1), 406–507. 10.2307/1158951

5

BuxtonJ. (1973). Religion and healing in mandari. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

6

CarrithersM.CandeaM.SykesK.HolbraadM.VenkatesanS. (2010). Ontology is just another word for culture: motion tabled at the 2008 meeting of the group for debates in anthropological theory, university of Manchester. Critique Anthropol.30 (2), 152–200. 10.1177/0308275X09364070

7

CastreeN. (2003). Environmental issues: Relational ontologies and hybrid politics. Prog. Human Geography27 (2), 203–211. 10.1191/0309132503ph422pr

8

CrateS. A. (2008a). Climate change and human rights. Anthropol. News49 (5), 34–35. 10.1525/an.2008.49.5.34

9

CrateS. A. (2008b). Gone the bull of winter: grappling with the cultural implications of and anthropology’s role(s) in global climate change. Curr. Anthropol.49 (4), 569–595. 10.1086/529543

10

CrateS. A. (2011). Climate and culture: anthropology in the era of contemporary climate change. Annu. Rev. Anthropol.40, 175–194. 10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.104925

11

de WitS. (2020). “What does climate change mean to us, the Maasai? How climate-change discourse is translated in maasailand, northern Tanzania,” in Global warming in local discourses: how communities around the world make sense of climate change. Editor BrüggemannM. (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers), 161–207.

12

DouglasM. (2002). Purity and danger: an analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. London: Routledge.

13

Evans-PritchardE. E. (1940). The Nuer: a description of the modes of livelihood and political institutions of a Nilotic people. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

14

Evans-PritchardE. E. (1951). Kinship and marriage among the Nuer. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

15

Evans-PritchardE. E. (1956). Nuer religion. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

16

FalgeC. (2008). Countering rupture: young Nuer in new religious movements. Sociologus58, 169–195. 10.3790/soc.58.2.169

17

FalgeC. (2015). “The global Nuer. Transnational life-worlds, religious movements and war,” in Köln: rüdiger Köppe verlag.

18

FergusonJ. (1990). The anti-politics machine: development, depoliticization, and bureaucratic power in Lesotho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

19

FoucaultM. (1984). The history of sexuality, volume 3: the care of the self, translated by R. Hurley. NY: Pantheon Books.

20

FoyerJ. (2016). Behind the scenes at the COP21. Books&Ideas, Transl. Fr. by M. Behrent. Available online at: https://booksandideas.net/IMG/pdf/20160526_cop21.pdf (Accessed September 4, 2025).

21

FoyerJ.KervranD. D. (2017). “Objectifying traditional knowledge, re-enchanting the struggle against climate change,” in Globalising the climate. Editors AykutS.FoyerJ.EdouardM. (London and New York: Routledge), 153–172.

22

FoyerJ.AykutS. C.MorenaE. (2017). “Introduction: COP21 and the “climatisation” of global debates,” in Globalising the climate. Editors AykutS.FoyerJ.EdouardM. (London and New York: Routledge), 1–17. 10.4324/9781315560595-1

23

Government of South Sudan (2018). Initial national communication to the united nations framework conversation on climate change. Available online at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/South%20Sudan%20INC.pdf (Accessed September 25, 2025).

24

GrabskaK. (2014). Gender, home and identity: Nuer repatriation to southern Sudan. Oxford: James Currey.

25

HarawayD. (2008). When species meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

26

HashimotoE. (2013). Reviving powers of the past with modern technology: aspects of armed youth and the prophet in Jonglei state. Sophia Asian Stud.31, 161–173.

27

HashimotoE. (2017). Prophecy and experience: dynamics of Nuer religious thought in post-independence South Sudan. Nilo-Ethiopian Stud.22, 1–14.

28

HashimotoE. (2018). “Transformation of marriage and kinship among Nuer refugees in Uganda,” in Diversification and reorganization of “family” in Uganda and Kenya: a cross-cultural analysis. Tokyo, Japan: Research institute for languages and cultures of Asia and Africa. Editors ShiinoW.ShiraishiS.MpyamguC., 77–86.

29

HerskovitsM. J. (1926). The cattle complex in East Africa. Am. Anthropologist28 (1), 230–272. 10.1525/aa.1926.28.1.02a00050

30

HoltzmanJ. D. (2000). Nuer journeys, Nuer lives: sudanese refugees in Minnesota. Massachusetts: Allyn and Bacon.

31

HutchinsonS. E. (1980). Relations between the sexes among the Nuer: 1930. Africa50, 371–387. 10.2307/1158429

32

HutchinsonS. E. (1985). Changing concepts of incest among the Nuer. Am. Ethnol.12 (4), 625–641. 10.1525/ae.1985.12.4.02a00020

33

HutchinsonS. E. (1992a). Dangerous to eat: Rethinking pollution states among the Nuer of Sudan. Africa62 (4), 490–504. 10.2307/1161347

34

HutchinsonS. E. (1992b). The cattle of money and the cattle of girls among the Nuer, 1930–83. Am. Ethnologist19 (2), 294–316. 10.1525/ae.1992.19.2.02a00060

35

HutchinsonS. E. (1996). Nuer dilemmas: coping with money, war, and the state. Berkeley: University of California Press.

36

HutchinsonS. E. (1998). “Death, memory and the politics of legitimation: Nuer experiences of the continuing second Sudanese civil war,” in Memory and the postcolony: african anthropology and the critique of power. Editor RichardW. (London: Zedbooks), 58–70.

37

HutchinsonS. E. (2001). A curse from god? Religious and political dimensions of the post-1991 rise of ethnic violence in South Sudan. J. Mod. Afr. Stud.39 (2), 307–331. 10.1017/S0022278X01003639

38

HutchinsonS. E.PendleN. R. (2015). Violence, legitimacy, and prophecy: Nuer struggles with uncertainty in South Sudan. Am. Ethnol.42 (3), 415–430. 10.1111/amet.12138

39

IOM South Sudan (2013). Humanitarian update issued in 2, May 2013. Available online at: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/migrated_files/Country/docs/IOM-South-Sudan-Humanitarian-Update-2-May-2013.pdf (Accessed September 4, 2025).

40

JohnsonD. H. (1981). The fighting Nuer: Primary sources and the origins of a stereotype. Africa51 (1), 508–527. 10.2307/1158952

41

JohnsonD. H. (1982a). Tribal boundaries and border wars: Nuer–Dinka relations in the sobat and zaraf valleys, c. 1860–19761. J. Afr. Hist.23 (2), 183–203. 10.1017/s0021853700020521

42

JohnsonD. H. (1982b). Evans-pritchard, the Nuer, and the Sudan political service. Afr. Aff.81 (323), 231–246. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a097410

43

JohnsonD. H. (1986). Judicial regulation and administrative control: customary law and the Nuer, 1898–1954. J. Afr. Hist.27, 59–78.

44

JohnsonD. H. (1994). Nuer prophets: a history of prophecy from the Upper Nile in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

45

JokJ. M.HutchinsonS. E. (1999). Sudan’s prolonged second civil war and the militarization of Nuer and Dinka ethnic identities. Afr. Stud. Rev.42 (2), 125–145. 10.2307/525368

46

KohnE. (2007). How dogs dream: amazonian natures and the politics of transspecies engagement. Am. Ethnol.34 (1), 3–24. 10.1525/ae.2007.34.1.3

47

KohnE. (2013). How forests think: toward an anthropology beyond the human. California: University of California Press.

48

KonakaS.SempliciG.LittleP. D. (2023). Reconsidering resilience in African pastoralism: towards a relational and contextual approach (Kyoto: Kyoto University Press).

49

LatourB. (2017). Facing gaia: eight lectures on the new climatic regime. Cambridge: Polity Press. Translated by C. Porter.

50

LeonardiC. (2007). Violence, sacrifice and chiefship in Central Equatoria, southern Sudan. Africa77 (4), 535–558. 10.3366/afr.2007.77.4.535

51

LeonardiC. (2011). Paying “buckets of blood” for the land: moral debates over economy, war and state in southern Sudan. J. Mod. Afr. Stud.49 (2), 215–240. 10.1017/S0022278X11000024

52

LienhardtG. (1961). Divinity and experience: the religion of the Dinka. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

53

MalkkiL. (1992). National geographic: the rooting of peoples and the territorialization of national identity among scholars and refugees. Cult. Anthropol.7 (1), 24–44. 10.1525/can.1992.7.1.02a00030

54

MalkkiL. (1995). Purity and exile: violence, memory, and national cosmology among hutu Refugees in Tanzania. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

55

NtumvaM. E. (2022). Land conflict dynamics in Africa: a critical review on farmer-pastoralist conflict perspectives. Int. J. Peace Dev. Stud.13 (1), 17–28.

56

OrloveB. (2009). “The past, the present and some possible futures of adaptation,” in Adapting to climate change: thresholds, values, governance. Editors AdgerW. N.LorenzoniI.O’BrienK. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 131–163.

57

PendleN. R. (2018). The dead are just to drink from: recycling ideas of revenge among the western Dinka, South Sudan. Africa, 88 (1), 99–121. 10.1017/S0001972017000584

58

PendleN. R. (2020a). Politics, prophets and armed mobilizations: competition and continuity over registers of authority in south Sudan’s conflicts. J. East. Afr. Stud.14 (1), 43–62. 10.1080/17531055.2019.1708545

59

PendleN. R. (2020b). The “Nuer of Dinka money” and the demands of the dead: contesting the moral limits of monetised politics in South Sudan. Confl. Secur. and Dev.20 (5), 587–605. 10.1080/14678802.2020.1820161

60

PendleN. R. (2023). Spiritual contestations – the violence of peace in South Sudan. Oxford: James Currey.

61

RileyK.JukesS.RautioP. (2024). Relational ontologies and multispecies worlds: transdisciplinary possibilities for environmental education. Aust. J. Environ. Educ.40 (2), 95–107. 10.1017/aee.2024.23

62

RoeE. (1994). Narrative policy analysis theory and practice. NC: Duke University Press.

63

RosaldoR. (1986). “From the door of His tent: the fieldworker and the inquisitor,” in Writing culture: the poetics and politics of ethnography. Editors CliffordJ.MarcusG. E. (Berkeley: University of California Press), 77–97.

64

RottenburgR. (2009). Far-fetched facts: a parable of development aid. MA: MIT Press. 10.7551/mitpress/9780262182645.001.0001

65

SchneggM. (2021). Ontologies of climate change: reconciling Indigenous and scientific explanations for the lack of rain in Namibia. Am. Ethnol.48 (3), 260–273. 10.1111/amet.13028

66

ScoonesI. (2023). Confronting uncertainties in pastoral areas: transforming development from control to care. Soc. Anthropology/Anthropologie Soc.31 (4), 57–75. 10.3167/saas.2023.04132303

67

SempliciG.HaiderL. J.UnksR.MohamedT. S.SimulaG.TseringL. P.et al (2024). Relational resiliences: reflections from pastoralism across the world. Ecosyst. People20 (1), 2396928. 10.1080/26395916.2024.2396928

68

ShandyD. J. (2007). Nuer-american passages: globalizing Sudanese migration. Florida: University Press of Florida.

69