Abstract

Pastoral systems operate within constrained ecosystems where livestock, wildlife, and human activities coexist. This coexistence, increasingly intensified by global environmental and socio-economic changes generates multiple, complex, and still insufficiently integrated risks. Understanding these dynamics is essential to ensuring the long-term sustainability of pastoral territories. This article aims to characterize the main risks affecting pastoral livestock systems at the interface with wildlife through a large diversity of conditions. Thus, we conducted a systematic literature search and screening process, analyzing a wide range of cases based on a corpus of 6,078 scientific publications identified through eight targeted search equations. This method is therefore structured around (i) conducting an initial quantitative, temporal, and thematic analysis to provide an overview of the research landscape, (ii) examining research themes and publications to identify dominant risk areas and their interconnections, and (iii) performing an in-depth analysis of the selected case studies in order to provide more detailed description of each identified risk. From this investigation, we developed a risk analysis framework structured around three broad categories: (1) biological and ecological risks (zoonoses, parasitic diseases, predation, and competition); (2) socio-economic risks (financial losses, conflicts, and psychosocial impacts); and (3) amplifying systemic risks (climate change, societal transformations, and habitat loss and fragmentation). This study highlights risks that are multiple, interwoven and deeply embedded within complex socio-ecological systems. It shows that risk should be understood as an interdisciplinary concept, allowing us to move beyond sectoral perspectives and to reveal the multidimensional nature of the interface between wildlife and pastoral livestock systems, where ecological, health, economic, and social processes interact. While wildlife can represent a source of risk for agropastoral activities, the latter are also sometimes considered as generating risks and gradually rendered illegitimate in certain territories, thereby fueling tensions around conservation objectives and territorial management practices. Moreover, the deterioration of human–nature relationships emerges as a latent risk that shapes the dynamics of both conflict and cooperation. In this perspective, the findings invite us to rethink risk management through an integrated and inclusive approach, grounded in cooperation across disciplines, institutions, and knowledge systems. Finally, this article calls for a reevaluation of the conditions for a sustainable coexistence between livestock and wildlife, understood as management practices and land-use strategies that support wildlife conservation while enhancing the resilience of pastoral systems, and advocates for a systemic and place-based approach to risk analysis in the face of global changes.

Introduction

Pastoral livestock systems play a central role in global socio-ecological systems. Based on the extensive use of natural habitat, herd mobility, and low inputs levels, they rely on adaptive management practices of rangelands resources, often complemented by agricultural activities. Occupying more than a third of the world’s terrestrial surface, particularly in arid, semi-arid and rangelands areas, they sustain millions of people’s livelihoods through their contribution to food security, cultural heritage, and biodiversity conservation (Dong et al., 2016; Reid et al., 2014; ILRI, 2021). However, these systems are increasingly exposed to socio-environmental pressures linked to global change such as climate variability, rangeland degradation and land-use transformations, conservation policies and institutional marginalization, or market volatility (FAO, 2007; Galvin and Ellis, 2008; Desta and Coppock, 2004). These dynamics threaten their resilience and reshape the ecological and institutional foundations on which they depend (Nori and Scoones, 2019; Dong et al., 2016).

In this context, pastoral systems stand at the center of contrasting debates regarding their sustainability and their role in environmental transitions. On one hand, they are increasingly valued for maintaining ecosystem services, preserving open landscapes, and providing low-input food production that is resilient to climate change (Behnke and Mortimore, 2016; Fernández-Giménez, 2020). On the other hand, they are often criticized for their vulnerability to market fluctuations and their contribution to land degradation and greenhouse gas emissions (Herrero et al., 2011). Pastoralism has also long been viewed as a driver of overgrazing, desertification, competition with wildlife for resources, and a direct threat to biodiversity (Alkemade et al., 2013). This consideration has fueled policies promoting a strict separation between conservation and production, at times leading to the exclusion of pastoral communities from protected areas, forced sedentarization, and restrictions on resource access (Homewood, 2008; Igoe and Brockington, 2002; Duffy, 2014). Due to their strong dependence on natural resource access and regularly interact with wildlife populations, pastoral systems are situated at the heart of shared ecological interfaces, where their compatibility with biodiversity conservation objectives is constantly questioned (Niamir-Fuller et al., 2012). Indeed, their proximity with wildlife generates both ecological interdependencies and conflictual interactions, including predation, disease transmission, resources competition, and land-use conflicts (Prins, 2000; Barroso and Zanet, 2024). Yet, this vision of inherent incompatibility between pastoralism and wildlife has been substantially revised in recent decades. Research on rangeland ecosystems has shown that their dynamics are primarily governed by climatic variability rather than livestock density. These systems operate under a non-equilibrium paradigm, where variability itself is the norm, and where mobility and flexibility in herding practices are effective adaptive strategies rather than drivers of degradation (Ellis and Swift, 1988; Behnke et al., 1994; Vetter, 2005). This shift in perspective has opened new ways of understanding the relationships between pastoralism and wildlife: under certain conditions, extensive pastoral systems can not only coexist with wildlife but also contribute to maintaining open landscapes, vegetation diversity, and habitat connectivity (Reid et al., 2014; Niamir-Fuller et al., 2012). This possible coexistence, however, remains fragile, shaped by multiple pressures and unevenly achieved across contexts.

The question is therefore no longer whether these systems can coexist, but how they can continue to do so in environments marked by uncertainty and rapid change. Promoting and sustaining coexistence requires a better understanding of the conditions that make it viable, particularly the risks that both affect pastoralism and wildlife populations. Indeed, interactions between wildlife and pastoral livestock create a mosaic of ecological, health, economic, and institutional risks that often reinforce one another (Barroso and Zanet, 2024; Virapin et al., 2025). Caught between these global debates, exposed to converging climatic, ecological, economic, and institutional pressures, and positioned at the heart of complex socio-ecological interfaces, pastoral systems appear increasingly vulnerable (Niamir-Fuller et al., 2012; Virapin et al., 2025). Understanding how these risks emerge, interact, and are managed within pastoral and rangeland systems is therefore essential for developing adaptive strategies that promote coexistence between pastoral activities, wildlife, and human societies.

Yet, the existing literature often addresses these risks in a fragmented manner, without fully considering the complexity of the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface. In this paper, risk is broadly understood as the combination of a hazard (ecological, health-related, economic or institutional) and a vulnerability (social, territorial or individual) that could affect the capacity of pastoral systems to remain functional and resilient over time. Viewed in this way, risk is understood as a cross-cutting concept linking different forms of hazards and vulnerabilities observed at the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface (Virapin et al., 2025). This interface thus represents a critical lens, still insufficiently integrated, for analyzing the complexity of intertwined risks that shape these socio-ecosystems. Examining this interface can reveal how ecological, socio-economic, and institutional processes interact to influence the resilience and vulnerability of pastoral systems. However, integrative analytical frameworks capable of capturing this multidimensionality remain scarce while it becomes essential to move beyond the lens of competition and conflict between pastoralism and wildlife, and to approach this interface through the prism of interdependence and coexistence. Developing a risk-analysis framework at the wildlife-pastoral livestock systems interface is therefore essential to better identify risks and interconnections, and to capture management strategies that support coexistence and resilience for both pastoral and wildlife systems.

Thus in this article, we aim to propose a framework to structure and analyze the main risks affecting agropastoral systems at the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface, by identifying their modes of interaction and their implications for pastoral systems. Our approach is based on the following research questions: What are the main risks at the interface between wildlife and pastoral livestock systems? How do these risks interact with one another? How are they addressed in management and adaptation strategies? This article is structured as follows: (1) presentation of the methodology and data corpus, (2) analysis of the identified risks, and (3) discussion of the dynamics at the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface with a view to fostering sustainable coexistence between pastoral activities and presence of wildlife.

Materials and methods

In the following section, we first introduce the conceptual framework and key equations used in this study, the corpus of publications analyzed, as well as the screening and selection process of the most relevant articles. It also details the types of analyses performed to address our research objectives.

Search equation and database

The development of our case search strategy followed an iterative approach. This trial-and-error process proved effective in identifying the most relevant formulation for our final search equation. Several conceptual frameworks were developed successively to build our case search equation. This framework enabled us to organize and structure the main ideas, key notions, and relationships surrounding our research topic.

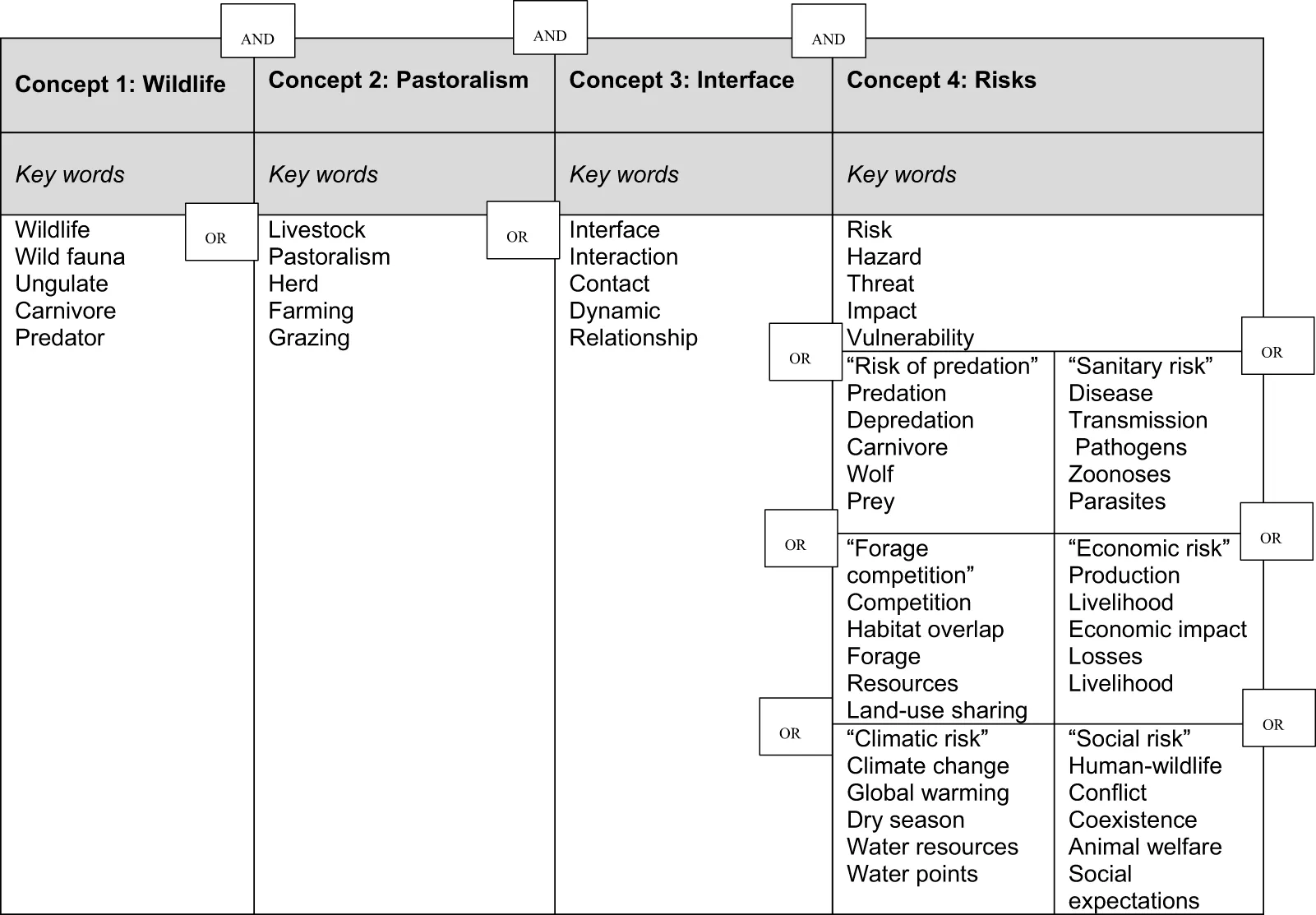

Our final conceptual framework is structured around four key concepts (

Table 1):

Wildlife, broadly referring to non-domesticated, free-ranging animal species that coexist in the same territories as domestic herds.

Pastoralism, specifically referring to extensive livestock farming systems.

The notion of interface, understood as the spatial and ecological zone of contact where wildlife and domestic livestock encounter and interact, either directly (through physical proximity or shared grazing) or indirectly (through the environment, such as water point, pastures, or vectors)

The notion of risk, which is broken down into several subcategories: risks related to predation, resource competition, health issues, economic impacts, social dimensions (tensions, coexistence), and climate change. A general “risk” category was also included to encompass more cross-cutting approaches. This breakdown of the concept of risk reflects its intrinsic complexity, which makes it unsuitable to be treated as a single, uniform category. The resulting structure provides a way to grasp both general and specific facets of the risks identified.

TABLE 1

|

Example of conceptual framework.

The main search equation, derived from the conceptual frameworks, is as follows:

((“wildlife” OR “wild ungulates”) AND (“livestock” OR “pastoralism”) AND (“risk” OR “hazard” OR “threat” OR “wildlife-livestock interface” OR “wildlife-livestock interactions” OR “disease transmission” OR “pathogens” OR “zoonoses” OR “parasites” OR “predation” OR “depredation” OR “carnivore” OR “competition” OR “habitat overlap” OR “forage” OR “economic impact” OR “economic losses” OR “human-wildlife” OR “conflict” OR “coexistence” OR “climate” OR “water resources” OR “water points”)).

The case search through international literature was conducted using the Web of Science database, selected for the breadth and quality of its publications. Additional resources (Scopus, ScienceDirect, HAL, Wiley), along with discussions with experts, helped identify other relevant references, including some that were recent or not widely disseminated.

To optimize the analysis and better highlight the different dimensions of the topic, the main search equation was broken down into eight thematic sub-equations. This approach allowed for a more in-depth exploration of the key concepts involved, while ensuring coherent and targeted coverage of the literature. Each sub-equation systematically incorporated the two core concepts of this topic (Tables 1, 2): pastoralism and wildlife (concepts 1 and 2), to ensure the relevance of the selected publications to our research focus. The concepts related to the interface (concept 3) and risk (concept 4) were treated as thematic entry points to be specified in each sub-equation. Thus, each sub-equation led to a targeted bibliographic search and a specific extraction of the resulting references. The period from 2010 to 2025 was chosen due to the limited number of relevant publications prior to 2010 and the significant increase in publication volume after that point (between 1990 and 2010: only 10% of the total, fewer than 100 publications per year). Only peer-reviewed articles and reviews were included in the analysis (98% of the total publications). In addition, the selection was refined using a set of Web of Science categories deemed most relevant to the topic. These include major disciplines related to ecology and environmental sciences (Ecology, Biodiversity Conservation, Environmental Sciences, Agricultural Multidisciplinary Sciences, Zoology), as well as complementary fields addressing the health, economic, and social dimensions of risk (Public Environmental Occupational Health, Economics, Geography, Veterinary Sciences, Parasitology, Infectious Diseases, Sociology). This approach resulted in a first qualified dataset, referred to as the Bronze database, comprising 6,078 references.

TABLE 2

| Key notions | Thematic sub-equations | Number of publications |

|---|---|---|

| Interfaces/interactions | ((“Wildlife” OR “wild ungulates”) AND (“livestock” OR “pastoralism”) AND (“wildlife-livestock interface” OR “wildlife-livestock interactions”)) | 222 |

| Risks/threats | ((“Wildlife” OR “wild ungulates”) AND (“livestock” OR “pastoralism”) AND (“risk” OR “hazard” OR “threat”)) | 1,473 |

| Sanitary | ((“Wildlife” OR “wild ungulates”) AND (“livestock” OR “pastoralism”) AND (“disease transmission” OR “pathogens” OR “zoonoses” OR “parasites”)) | 849 |

| Predation | ((“Wildlife” OR “wild ungulates”) AND (“livestock” OR “pastoralism”) AND (“predation” OR “depredation” OR “carnivore”)) | 1,160 |

| Competition | ((“Wildlife” OR “wild ungulates”) AND (“livestock” OR “pastoralism”) AND (“competition” OR “habitat overlap” OR “forage”)) | 467 |

| Economy | ((“Wildlife” OR “wild ungulates”) AND (“livestock” OR “pastoralism”) AND (“economic impact” OR “economic losses”)) | 155 |

| Social | ((“Wildlife” OR “wild ungulates”) AND (“livestock” OR “pastoralism”) AND (“human-wildlife” OR “conflict” OR “coexistence”)) | 1,325 |

| Climate | ((“Wildlife” OR “wild ungulates”) AND (“livestock” OR “pastoralism”) AND (“climate” OR “water resources” OR “water points”)) | 427 |

| Total of publications (bronze database) | 6,078 | |

Dataset and distribution according to the 8 thematic search sub-equations.

Screening and selection of relevant publications

A thematic classification was then carried out for each sub-database using the Carrot2 clustering software (Figure 1). This open-source tool, designed for automatic grouping and thematic organization of textual documents, relies on advanced natural language processing techniques and clustering algorithms to organize text corpora into coherent thematic groups, known as clusters. Several adjustable parameters allow for optimization of the quality of the thematic clusters generated: handling of high-frequency words to reduce textual noise and focus the analysis on more meaningful terms; specification of the desired number of clusters; and selection of the clustering algorithm, which allows the granularity and relevance of the groupings to be modulated by balancing precision and comprehensiveness in the processing of textual data. The consistency of the main groups was also assessed qualitatively on a small subset of data to ensure that the automated classification reflected meaningful thematic distinctions within the corpus.

FIGURE 1

From this thematic classification, for each sub-database, we retained the five most prominent thematic clusters (based on publication volume), as well as a few smaller clusters that were of particular interest for this study, notably those addressing key but understudied notions such as the wildlife–livestock interface (“Wildlife–Livestock Interface in Africa” or “Interaction Patterns”, clusters no. 7 and 11 from the “Interface” sub-database, Table 3). Then, a manual analysis of the article titles and abstracts from the clusters was conducted to refine the bibliographic selection based on thematic and contextual relevance.

TABLE 3

| Key notions by sub-equations | Number of clusters | Average number of publications per cluster | Examples of clusters and their ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competition | 52 | 9 | Livestock predation (1), overlap with livestock (4), conflicts over wildlife (7), grassland forage (10) |

| Climate | 51 | 8 | Reduced water (17), global health (25), seasonal patterns (27), parasite dynamics (40) |

| Economy | 31 | 5 | Economic losses for farmers (1), human-wildlife conflict (2), economic loss per household (4), economic impact of predation (6) |

| Interface | 51 | 4 | Wildlife conservation (1), wildlife-livestock interface in africa (7), interaction patterns (11), infectious diseases at the wildlife-livestock interface (17), barrier fence (48) |

| Predation | 57 | 20 | Carnivore depredation of livestock (1), increasing risk (6), livestock predation risk (12), conflict management strategies (14) |

| Risk | 54 | 28 | Conflicts over livestock depredation (1), disease risk (7), human-wildlife conflict management (24), potential risk to human (36) |

| Sanitary | 61 | 14 | Parasites in humans (2), zoonotic infections (5), livestock wildlife interface (13), tick and pathogen (42) |

| Social | 57 | 23 | Protected wildlife areas (3), livestock damage (11), coexistence between humans and wildlife (34), attitudes toward wildlife conservation (44) |

Number and examples of clusters by thematic sub-database.

The selection was guided by a central principle: identifying studies that focus on socio-ecological contexts in which the coexistence of livestock and wildlife generates multiple, interwoven risks. Articles focusing on tropical, humid, or aquatic species (such as those from equatorial forests or marine ecosystems) were excluded due to their limited applicability to the context under study. Indeed, we focused on species commonly associated with pastoral ecosystems, defined here as open or semi-arid landscapes where livestock grazing is a dominant land use. These include large carnivores (wolves, bears, lynx, lions, etc.) and large herbivores (ungulates such as antelopes, chamois, ibex, etc.) that typically interact with livestock through predation, competition for forage, or shared disease dynamics. This selection of species was guided by recurrent taxa identified in the corpus studied. Studies conducted in arid, or desert environments were also included for their eco-anthropic dynamics with strong constraints on natural resources, territorial marginality, land-use conflicts, and the adaptability of pastoral systems. This choice allows for the consideration of alternative forms of resilience in similarly vulnerable ecosystems. Publications adopting a systemic and integrated approach were preferred over those with a purely technical or specialized focus, to explore more broadly the dynamics, perceptions, and strategies related to the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface. Particular attention was given to articles addressing multiple types of risk simultaneously (e.g., predation and economic impact; disease and climate change), to better capture the complexity of the interactions under study.

We propose a deep analysis of risks through a double step method: (1) an initial selection process identified 350 relevant studies (Silver database), followed by (2) a second selection that resulted in 150 situations retained for in-depth analysis (Gold database). These were integrated into Zotero and coded according to methodological and thematic criteria. Publications were organized into three subsets reflecting increasing levels of thematic relevance and analytical details:

The Bronze database (6,078 publications from eight sub-databases),

the Silver database (350 pre-selected articles),

and the Gold database (150 articles analyzed in depth).

Analysis of the databases

In order to identify the diversity of risks and their relationships, we develop a specific method designed for this study. The analysis of the database was therefore conducted in two stages (

Figure 2):

Descriptive analyses of the databases: including quantitative analysis, temporal trends, and semantic analysis.

FIGURE 2

Based on the Bronze database (the full corpus), an initial analysis focused on the temporal evolution of themes since 1990, as well as a quantitative and thematic analysis (clusters, co-occurrences) aimed at identifying dominant research areas and their interconnections. A structural analysis was also carried out by examining the co-occurrence of themes and studies across the multiple sub-databases. This analysis made it possible to (i) explore the overlaps between thematic clusters within the sub-databases and (ii) assess the actual documentary overlaps, i.e., instances where the same article was classified under multiple bibliographic queries. Three levels of analysis were considered regarding article classification: (a) Level 1 duplicates: articles shared between two sub-databases; (b) Level 2 duplicates: articles shared between three sub-databases; and (c) Level 3 duplicates: articles shared between four sub-databases. These overlaps were also visualized using heatmaps and co-occurrence graphs.

2. Analysis of selected publications: analytical framework of risks at the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface.

A second more in-depth level of analysis was conducted on the most relevant articles (Silver database: 350 articles; Gold database: 150 articles) to identify the main risks, their interactions, and the key issues associated with the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface. Based on a structured review of the selected publications (Silver and Gold databases), we organized the identified risks into three main analytical categories. These bases also served to support the argumentative structure developed in the discussion section. In total, 80 references were used in this article.

Results

The results are presented in two parts. At first, (1) we develop the results of the descriptive analyses of the databases with in particularly (i) the quantitative and temporal analysis; (ii) cross-analysis of thematic areas and (iii) cross-analysis of the documentary overlaps. Then in a second part, (2) we expose the results of the analytical framework of risks identified, connected to pastoral livestock systems related to the wildlife interface through three categories of risks: (i) biological and ecological risks (zoonoses, parasitic diseases, predation, and competition); (ii) socio-economic risks (financial losses, conflicts, and psychosocial impacts); and (iii) amplifying systemic risks (climate change, societal transformations, and habitat loss and fragmentation).

Descriptive analyses of databases

Quantitative analysis and temporal evolution

This part provides an overview of the quantitative distribution and temporal evolution of publications within the bronze database, highlighting the dominant thematic areas and how their prominence has changed over time.

Three main sub-databases stand out within the initial bronze database (2010–2025) (Figure 2): “Risks” (1,473 articles, 24.6%), “Social” (1,325 articles, 21.7%), and “Predation” (1,160 articles, 19%). Together, these three thematic sub-databases account for nearly 66% of all publications, reflecting a strong interest in these dimensions within the literature. Conversely, certain categories such as “Interface” (222 articles, 3.6%) and “Economy” (155 articles, 2.5%) are significantly less represented. This limited representation may indicate a lower use of these approaches in the reviewed studies or reflect more emerging and less documented analytical perspectives in the current literature.

The temporal analysis (Figure 3) reveals a general increase in the number of publications related to all the concepts included in our search equation since the 1990s. A peak in publications is observed around 2020–2021. However, from 2021 onward, a slight stagnation, or even a decline, is noticeable in the volume of publications across most of our thematic areas. The “Climate” and “Interface” sub-databases particularly illustrate this trend: both reached their highest publication levels in 2021 (with 44 and 84 publications respectively), followed by a sharp drop, proportional to their initial share within the overall database. This decline may suggest a shift in scientific priorities.

FIGURE 3

Cross-analysis of thematic areas

This subsection examines the internal structure of the sub-databases and to identify their areas of overlap or separation. Cross-comparisons between sub-corpora allowed us to explore how the main themes are organized, interconnected, or, conversely, remain compartmentalized.

Internal semantic structuring via clustering

The thematic analysis conducted using Carrot2 automatic clustering provided a semantic mapping of the corpus by thematic sub-database. The number of clusters generated for each sub-database ranges from 31 to 61, reflecting the lexical richness and thematic diversity of the content. Similarly, the average number of articles per cluster serves as a complementary indicator, helping to assess the degree of thematic centralization or fragmentation (Table 3). For example, the “Interface” sub-database stands out with a particularly low average of 4 publications per cluster, suggesting a fragmented theme, potentially heterogeneous in both its research objects and disciplinary approaches. In contrast, themes such as “Predation”, “Social”, and “Risks” show higher averages (ranging from 20 to 28 articles per cluster), indicating a more clearly defined thematic structure, organized around shared conceptual cores (e.g., predator management, social perception of risk, human–wildlife conflict). These results highlight the heterogeneity and complexity of the thematic landscape covered by the article corpus (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4

Thematic overlap between sub-databases based on clusters

To assess thematic convergence and semantic overlap between the different sub-databases, we analyzed cluster co-occurrence using a heatmap. A high number of identical clusters across sub-databases indicates a strong degree of thematic interconnection.

Some sub-databases, such as “Predation”, “Risks” and “Social”, show high levels of overlap with other themes, suggesting strong interconnection of issues and recurring semantic groupings (Figure 4). Notably, the “Predation” and “Social” sub-databases share 16.1% of their clusters, while the “Risk” sub-database shares 15.1% of its clusters with “Social”. Several clusters appear to be transversal, such as “Livestock by Lions” (shared by “Predation”, “Risks” and “Social”), “Carnivore Conflict Mitigation” (“Risks”, “Social”), “Conflict Mitigation Strategies” (“Predation”, “Social”), and “Wolves and Livestock” (“Risks”, “Social”). Contrastingly, sub-databases such as “Climate”, “Competition”, “Health”, and “Interface” appear more isolated, sharing few clusters with other thematic areas. For example, the “Interface” sub-database shares no clusters with “Predation”, “Risks” or “Social”. However, it does share clusters with the “Economy” sub-database (8% of shared clusters, equivalent to 4 clusters), such as “Red Deer” or “Bovine Tuberculosis BTB”, and with the “Competition” sub-database (4%, or 2 clusters), including the “Elk Cervus” cluster.

It is important to emphasize that articles shared across clusters do not necessarily address the key concepts in a systemic manner. Although some articles do appear as duplicates within identical clusters in two thematic sub-databases, this represents only a thematic overlap rather than an analytical intersection of multiple risks. Conversely, there are a few rare linkages despite the absence of a shared cluster: for example, the “Dry Season” cluster, referring to climate risk, occurs in both the “Interface” and “Competition” sub-databases.

These results highlight the structuring role of major themes in the conceptual architecture of the corpus. These dominant themes often serve as points of convergence across multiple dimensions. In contrast, more modest themes tend to be addressed more independently, reflecting either a lack of terminological convergence or limited integration into broader cross-cutting debates. This fragmentation may reflect the nature of an emerging or multidimensional theme, or a thematic field still in the process of structuring, where multiple paradigms coexist.

Cross-analysis of documentary overlaps

We analyze here how the various bibliographic sub-databases overlap in terms of shared references. This approach helps identify cross-cutting studies that link multiple dimensions of the human–wildlife–livestock interface.

Analysis of articles shared between two sub-databases (level 1 duplicates)

The analysis of article co-occurrences between two thematic sub-databases highlights observable patterns. Certain thematic associations appear particularly frequent within the corpus, revealing research areas that are already well-established and actively explored. This is particularly true for the intersections between the “Predation”, “Risk” and “Social” sub-databases, which together form a central core within the corpus (Figure 5). The “Predation” sub-database, for example, is extensively explored through the lenses of “Risk” (89% of shared articles) and “Social” (78%). The interconnection is similarly strong in the other direction: 70.1% and 58.6% of the articles in the “Risk” sub-database are also found in the “Predation” and “Social” sub-databases, respectively. Likewise, the social theme maintains strong links with “Predation” (68.3%) and “Risk” (65.2%). This strong association highlights the importance of social factors in how predation and risk are framed. It reflects a growing trend to integrate local perceptions, community responses, and social dynamics into the analysis of human–wildlife conflicts.

FIGURE 5

Beyond this central triptych, other thematic intersections also emerge significantly. Notable examples include the interaction between the “Competition” and “Social” sub-databases (31.5%), as well as between “Economy” and the “Risk” (46.8%), “Social” (32.5%), and “Predation” (33.1%) sub-databases. The “Interface” theme is primarily addressed from a health-related perspective, with nearly 38% of its articles falling under this dual classification. Alternatively, some intersections remain only marginally explored, such as those between “Climate” and “Economy” (1.9%), “Competition” and “Economy” (1.3%), or “Predation” and “Interface”, which account for only 0.5% of the articles. Overall, the concept of interface appears to be weakly connected to other thematic areas, except in relation to health issues.

Analysis of articles shared between three sub-databases (level 2 duplicates)

We extended this logic to a higher level of granularity by identifying articles that appear in three sub-databases. This Level 2 analysis makes it possible to explore triangular configurations that reveal the presence of multiple themes. As with the clusters, however, the number of shared articles across sub-database triplets does not necessarily indicate that these articles address all three key concepts through a systemic approach.

As shown in Figure 6, the “Predation”– “Risk”– “Social” triplet shares between 30% and 33% of articles within their respective triplet combinations. The inclusion of these sub-databases in a triplet tends to increase the observed percentages. More broadly, beyond this central core, there are very few, if any, shared articles across most sub-database triplets. For example, only 0.6% of articles (4 articles) are shared in the “Interface”– “Health”– “Climate” triplet. More generally, predation does not appear to be addressed through the lens of interface, but rather through that of risk. To take the analysis further, the examination of triplets also enables exploration of triangular thematic configurations (Figure 7). This figure presents a network graph where: (1) sub-databases are represented as nodes; and (2) shared articles between sub-databases are represented as links, with line thickness proportional to the strength of the relationship. This representation of conceptual nodes illustrates the arrangement of themes in relation to one another. The themes related to “Risk” “Predation” and “Social” occupy central positions. In contrast, the “Interface” and “Economy” sub-databases are relatively peripheral, highlighting thematic nodes that are less cross-cutting.

FIGURE 6

FIGURE 7

Analysis of articles shared between four sub-databases (level 3 duplicates)

An exploration was conducted on the co-occurrences of articles belonging simultaneously to four distinct sub-databases: no articles in the corpus were found to be present in four different sub-databases at the same time. This absence of documentary quadruplets suggests a strong thematic compartmentalization, where multiple intersections remain rare or even nonexistent. Articles appear to be primarily organized around thematic pairs or triplets, without crossing a higher threshold of transversality.

Finally, the analysis of thematic and documentary intersections of risks reveals three central poles in the corpus: the notion of risk, the predation, and the social dimension, which are often addressed jointly and reflect a strong focus on dynamics of vulnerability and conflict. Predation emerges as a key convergence node, whereas the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface remains surprisingly marginal, except through the health-related lens. Conversely, the social dimension appears as a transversal prism mobilized across numerous axes. Certain themes, such as economy and interface, are also weakly connected to other dimensions, limiting systemic understanding. These imbalances suggest that the approaches remain compartmentalized and highlight the need to strengthen cross-cutting analyses, particularly around the interface, a key yet underexploited concept in the literature.

Beyond these thematic insights, the approach developed in this study also constitutes an original methodological contribution. By combining automatic clustering with cross-thematic analysis, it enables a structured and efficient identification of conceptual associations between risks. This dual-level method reveals not only dominant thematic poles but also overlooked or compartmentalized areas that would remain hidden in traditional literature reviews. Its implementation is relatively easily replicable, thanks to open-source tools and systematic protocols. More broadly, this framework could be extended to other fields of risk analysis (e.g., health, climate, technological or political risks), where cross-cutting issues and fragmented knowledge are common challenges. As such, it offers both a diagnostic tool and a strategic lens for fostering integrative thinking in interdisciplinary research.

Analytical framework of risks identified in pastoral livestock systems related to the wildlife interface

The second part of the results focuses on the analytical framework developed to classify and interpret the different types of risks identified in pastoral livestock systems at the wildlife interface. Indeed, the analysis of the thematic groupings revealed that most studies address interactions between livestock farming and wildlife through situations of exposure, uncertainty or vulnerability. This research uses the concept of risk to describe the effects of predation, health threats linked to infected wildlife, and tensions surrounding the management of animal populations in shared spaces. This inductive approach leads to the distinction of three main categories of risk, corresponding to the most recurrent dimensions in the literature: (1) biological and ecological risks, (2) socio-economic risks, and (3) systemic amplifying risks linked to global changes.

Biological and ecological risks

Biological and ecological risks at the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface encompass three main dimensions: animal health risks, predation risks that disrupt the balance between herders and wildlife, and risks related to the use of shared natural resources.

Parasitic, zoonotic, and health risks: active epidemiological interfaces

The interfaces between pastoral livestock and wildlife constitute dynamic spaces of cross-transmission, where pathogens of diverse origins, bacterial, parasitic, or viral, coexist. These interfaces, characterized by shared use of space (pastures, water points, shelters), are particularly conducive to the emergence and persistence of diseases.

Several studies highlight a significant eco-parasitic continuity between wild and domestic species. Anderson et al. (2011) demonstrated active trypanosome circulation in the Luangwa Valley (Zambia) among a wide diversity of wild hosts (antelopes, buffaloes, lions, leopards), transmitted by the tsetse fly (Glossina spp.). Similarly, Smith and Parker (2010) showed that the tick Rhipicephalus appendiculatus, vector of Corridor disease, is exclusively present in wildlife-livestock cohabitation zones (notably within a narrow cattle migration corridor between Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania), underscoring the role of these shared interfaces in maintaining complex parasitic cycles. Likewise, Berggoetz et al. (2014) identified water points and grazing areas as hotspots for parasitic transmission. Titcomb G. et al. (2021) suggested that water points act as nodes intensifying indirect contacts, facilitating environmental persistence and transmission of eggs, larvae, and vectors. The spatio-temporal distribution of these parasites is particularly influenced by dry seasons, habitat fragmentation, and environmental stress episodes (drought, overgrazing), which concentrate animals around scarce resources (Titcomb G. et al., 2021). Finally, Barone et al. (2020) more broadly identified wild ruminants as significant reservoirs of gastrointestinal nematodes for livestock. Vasileiou et al. (2015) also highlighted strong parasitic similarities between domestic small ruminants and wildlife. This observed parasitic convergence likely results from frequent indirect contacts related to shared use of pastoral resources and the permeability of ecological interfaces.

The interface between wildlife and pastoral livestock systems also constitutes a major vector for zoonoses. In the United States, Miller et al. (2013) demonstrated that, among the 86 diseases reported by the World Organization for Animal Health, 79% involve a wildlife component and 40% are zoonotic. In Spain, Rodríguez et al. (2011) highlighted that Mycobacterium caprae circulates among several domestic and wild animal species, representing a concerning zoonotic reservoir. Its resistance to treatment and diagnostic challenges make its control and management particularly complex in both animal and human populations. In Tanzania, Katale et al. (2013) also describe the co-occurrence of bovine tuberculosis (Mycobacterium bovis) in buffalo and cattle within the Serengeti. They highlight the amplifying effect of shared natural resources (habitats, grazing, and watering areas).

Furthermore, beyond the transmission of zoonotic or parasitic agents, the interface reveals systemic health vulnerabilities linked to species coexistence, ecological dynamics, and livestock management practices. Navarro-Gonzalez et al. (2016) notably demonstrated that foodborne pathogens such as Salmonella and Campylobacter can be transmitted from wildlife (wild boars, cervids, birds) to domestic animals, thereby threatening the safety of animal products (meat, milk) and various levels of the food supply chain. The consumption of game meat represents an emerging source of human contamination, with wild boars being known carriers of zoonotic pathogens (Mentaberre et al., 2013).

More broadly, Mbizeni et al. (2013) add that the absence of physical barriers (fences, zoning, sanitary regulations) exacerbates the spread and persistence of pathogens, thereby amplifying the structural vulnerabilities inherent to extensive systems. Similarly, Meurens et al. (2021) emphasize that habitat fragmentation, globalization of trade, and climate change promote the emergence of new pathogens, reinforcing the need to monitor these interfaces as high epidemiological risk zones.

Far from being passive and impermeable boundaries, wildlife–pastoral livestock interfaces are dynamic epidemiological systems. Interconnected from local to global scales, the interfaces are structured by the diversity of hosts, the frequency and nature of spatial interactions, animal mobility, and by environmental, health, and social transformations.

Predation risk: conflictual and tense interfaces with wildlife

Beyond the economic impacts caused by predation, which will be discussed in a later section, predation acts as a structural factor transforming livestock practices, reorganizing production strategies, activity schedules, and economic trade-offs within pastoral systems.

Beattie et al. (2020) notably highlight the variability of predation according to seasons and landscape configuration. They identify specific high-risk areas and periods for lion predation within a multi-use context (Tanzania): during the dry season, predation is more frequent in dense vegetation zones, while in the wet season, it concentrates around enclosures. In both cases, proximity to water points increases the risk. These findings emphasize the variable nature of predation, which depends both on prey abundance and accessibility.

In general, herders are encouraged to intensify preventive measures such as improving nighttime enclosures, increasing surveillance, using more guard dogs, and altering grazing schedules and locations. In France for example, strategies combining physical barriers (electric fences) and active monitoring (protection dogs or increased human presence) are strongly recommended. Multifunctional approaches tend to be more effective than isolated solutions, but they require significant human and economic investment, which may hinder their widespread adoption (Bruns et al., 2020). Other non-lethal measures, such as fladry (visual deterrent banners), have also shown some potential to temporarily discourage predators. However, their effectiveness tends to be limited over time: Windell et al. (2022) observed that while coyotes initially avoided protected areas, they later adapted their behavior by circumventing or actively exploring peripheral zones, thus reducing the deterrent effect. Similarly, in the United States, initiatives like the Wood River Wolf Project rely on cooperation among herders, NGOs, and authorities to test and promote these non-lethal tools within a framework of collaborative coexistence (Martin, 2021).

However, technical tools alone are insufficient to ensure sustainable coexistence. Success also depends on social factors: trust among stakeholders, shared governance, adaptability to local conditions, and long-term commitment (Martin, 2021). Thus, although herders acknowledge the importance of financial compensation for livestock losses due to [wolf] attacks, these measures alone are insufficient to significantly improve their tolerance towards large predators (Milheiras and Hodge, 2011). Bautista et al. (2019) notably emphasize that predator attacks are often perceived as symptoms of an imbalance in conservation policies, which are viewed as more protective of wildlife than of the needs of local communities. This perception is especially pronounced in contexts where access to compensation mechanisms is limited, unequal, or bureaucratic (Bautista et al., 2019). Alvares et al. (2011) also demonstrate that symbolic and cultural representations of the wolf strongly influence social tolerance, independent of actual economic losses. Their study, conducted in the Iberian Peninsula, highlights a rich ethnographic heritage shaped by centuries of coexistence between pastoral communities and wolves. This intangible heritage, composed of myths, stories, and traditional practices, contributes to forging two contrasting perceptions: the wolf as a concrete threat and the wolf as an animal imbued with symbolic meanings. These representations underscore the importance of integrating cultural dimensions into conservation and conflict management strategies. Alvares et al. (2011) thus stress that cultural issues are as significant as actual economic losses. Similarly, Jacobsen et al. (2021) emphasize that lived experiences, beliefs, and the history of coexistence shape conflicts, sometimes more than tangible losses. Their surveys reveal that emotional and cultural variables can be more decisive than socio-economic indicators. These findings call for a more holistic approach to coexistence, one that takes into account the subjective and symbolic dimensions of human–carnivore relationships.

Predation is not simply a material issue or something that can be quantified by livestock losses; it takes place within complex socio-ecological dynamics involving land use, social perceptions of wildlife, and the balance between human groups and natural environments. This systemic dimension explains why some risk management approaches, focused on financial compensation or technical measures, often struggle to gain local acceptance. These approaches are sometimes seen as disconnected from the lived realities of herders or as inadequate in the face of feelings of injustice, loss of control, or marginalization in wildlife governance. Such frustrations can lead to counterproductive direct responses such as trapping, poisoning, or retaliatory shootings, which increase pressure on predator species, often already threatened, and weaken conservation efforts (Thinley et al., 2021; Aryal et al., 2014).

Competition risk for resources: shared ecological interfaces

In many regions with high coexistence between wildlife and extensive livestock systems, competition for essential resources such as pasture and water points generate a conflictual dynamic. Martinez et al. (2024) demonstrate how seasonal droughts force wild herbivores and livestock to gather around the same water points. Similarly, in the Spanish Mediterranean regions, Triguero-Ocaña et al. (2019) highlight frequent shared use of pastures between cattle and wild boars, with peaks in interactions during periods of abundant vegetation and water. These regular contacts, intensified by overlapping activities during twilight hours and concentration around shared resources, not only foster competition but also facilitate the cross-transmission of parasites and pathogens (Martinez et al., 2024; Triguero-Ocaña et al., 2019).

Beyond direct competition for forage and water resources, Raimondi et al. (2023) highlight that the presence of domestic livestock leads to spatial exclusion of wild ungulates from water points, observed as a complete segregation of space between species. This phenomenon, noted at the end of the dry season, appears to rely on a spatial niche partitioning mechanism, with wild species adapting their behavior to avoid direct competition with livestock in a context of critical resource scarcity. Ogutu et al. (2014) also highlight the combined influence of water, grazing, and pastoralism on the distribution of ungulates in the Kenyan savannas, noting that human land use can restrict access to water and alter the composition of herbivore communities. Similarly, Connolly et al. (2021) observed in the South Rift Valley (Kenya) that livestock and wildlife access water points according to a marked temporal partition between day and night. When herders and their livestock settle near these resources, wild animals adjust their behavior to visit water points mainly at night, when livestock are confined in enclosures. This co-adaptation helps reduce direct competition despite intense pressure on shared resources (Connolly et al., 2021). Fynn et al. (2016) even suggest territorial planning that includes zoning, movable fences, and local community involvement to reconcile conservation and pastoralism. Raimondi et al. (2023) emphasize that physical separation at water points could prevent wildlife from being excluded by domestic herds.

Furthermore, Titcomb G. C. et al. (2021) highlight how the aggregation of herbivores around water sources in savannas can have negative effects on plant communities and soils. Similarly, Vargas et al. (2022), in the Chilean Andes, demonstrate how overlapping territories of livestock and wildlife lead to overexploitation of shared resources and contribute to a loss of resilience in pastoral systems facing climatic and environmental hazards.

These dynamics reveal that competition for natural resources is not one-sided: both wildlife and domestic herds experience the effects of coexistence. On one hand, wild animals may be excluded from water points or strategic grazing areas; on the other hand, herders face losses of forage resources, risks of disease transmission, and predation. Resource management is therefore a central issue for both ecosystem management and the resilience of pastoral systems.

Socio-economic risks

Two particularly sensitive dimensions emerge: economic vulnerabilities that affect the very survival of the activity, and psychosocial vulnerabilities, often subtle but equally decisive in shaping herders’ trajectories.

Economic risk: insights into farm viability

Biological and ecological risks can lead to significant economic consequences. Production losses linked to the presence of wildlife and additional costs related to risk management are highlighted in several studies. Keesing et al. (2018) state that parasite risk prevention requires regular veterinary treatments for livestock, representing a considerable additional expense for herders. Similarly, while some integrated management practices (acaricide treatments, chemical control measures) can reduce health risks, they imply substantial health-related investments (Chakraborty et al., 2023).

Furthermore, according to Aryal et al. (2014), predation by large carnivores in Nepal (snow leopards, wolves, and tigers) accounts for over 30% of the annual livestock losses in the affected extensive farming systems. These recurrent losses also fuel a sense of abandonment among pastoral communities, often exacerbated by the absence or ineffectiveness of compensation schemes. Similarly, in Bhutan, losses attributed to snow leopards and Tibetan wolves’ amount to 10.2% of the annual per capita income, leading some herders to reduce their herds or abandon livestock farming entirely in favor of other economic activities (Jamtsho and Katel, 2019). Muriuki et al. (2017) assessed the economic losses related to livestock predation by wildlife, such as hyenas, leopards, cheetahs, baboons, jackals, elephants, and lions, on a community ranch near Amboseli National Park in Kenya.

Lions are responsible for 40.5% of the total value of livestock losses caused by wildlife. Braczkowski et al. (2023) also highlight an economic vulnerability related to livestock predation that is 2–8 times higher in developing or transitional countries than in developed countries, due to the relative impact of losses on per capita income. This inequality is further exacerbated by lower livestock productivity in developing countries, where each animal produces on average 31% less meat than in developed contexts. The loss of a single bovine in the poorest regions can represent up to 1.5 years of calories for a child, underscoring the direct impact on food security. This study highlights an “unequal burden” of human–carnivore conflicts, calling for the reconciliation of multiple sustainable development goals, particularly those related to biodiversity conservation and the fight against poverty and hunger.

Finally, managing the risk of resource competition also incurs additional costs for herders. Raimondi et al. (2023) demonstrate that competition for water points in the Gobi Desert involves operational costs in terms of labor (increased monitoring) and mobility (relocation to other water points). Similarly, restrictions on access to natural resources, whether fences, grazing bans, or conservation zones, can weaken pastoral systems, especially in regions facing increasing climate stress. Boone et al. (2024) highlight, in East Africa under drought conditions, that limiting herd access to central resources within protected areas results in significant livestock losses, reduced milk production, and decreased incomes for pastoral households.

According to Benka (2023) in Kenya, exclusion policies can conflict with herders’ mobility practices, compromising their economic security and exacerbating local tensions. This study notably emphasizes that managing shared resources cannot overlook the needs of dependent populations. Thus, risks related to the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface are not limited to direct losses of livestock or production. They also generate indirect but significant costs, including health expenses (zoonosis prevention, vector control), adaptation of practices (strengthening fences, additional movements), and reduced access to natural resources (water, pasture). These costs, often borne solely by herders, undermine the economic viability of pastoral systems, especially in contexts of precariousness or climate vulnerability.

Psychosocial risks: an invisibility with critical consequences

Human–wildlife conflicts are not limited to economic or material losses but also give rise to significant and often overlooked psychosocial risks. Yeshey et al. (2024) notably show that individuals repeatedly affected by attacks on their crops or livestock, particularly among the most vulnerable households (single women, poor families), experience high mental stress. The authors emphasize that these situations cause fear, anxiety, sleep disturbances, loss of peace of mind, and a constant feeling of insecurity, profoundly impacting psychological wellbeing. This chronic stress can also impair social and family relationships, especially when herders bear alone the mental burden related to household survival. Barua et al. (2013), through a cross-disciplinary review, highlight the “hidden” costs of human–wildlife conflict, often overlooked in management frameworks: emotional distress, time devoted to monitoring, psychological exhaustion, and loss of economic opportunities. The accumulation of these burdens, though less visible than material losses, undermines tolerance toward wildlife and reduces the effectiveness of compensation policies. More broadly, these studies call for recognizing emotional and psychological impacts in management strategies, on par with economic and ecological losses.

Amplifying systemic risks

Amplifying systemic risks refer to large-scale, non-localized threats that exacerbate other risks present at the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface. They affect the entire system, trigger cascading effects, and intensify existing vulnerabilities.

Environmental changes: habitat fragmentation as a destabilizing factor of the interfaces

Habitat fragmentation increases the interfaces between wildlife and pastoral livestock systems, intensifies health risks, predation, and competition for resources, while weakening conservation efforts through population isolation and disruption of ecological dynamics. In South Africa, Dion and Lambin (2012) notably show that the expansion of human settlements on the outskirts of protected areas, coupled with extensive livestock farming, intensifies wildlife–livestock interactions and increases the risks of disease transmission, such as foot-and-mouth disease.

In northern Israel, Preiss-Bloom et al. (2025) demonstrate that wolves persist across all types of areas in a fragmented landscape (pastoral, military, agricultural, and protected zones), including those with high conflict risk with livestock (with 25% of the population culled annually). Their persistence is explained by behavioral flexibility, notably increased nocturnal activity, and their ability to exploit the landscape mosaic to adapt their spatial use according to risk levels. This spatial heterogeneity prevents uniform regulation, thereby limiting the effectiveness of control measures and complicating conflict management with livestock.

Complementarily, Hawkinson et al. (2025) indicate that habitat fragmentation increases the risk of livestock predation, especially when seasonal grazing exposes herds to poorly monitored areas. While grazing types have little direct effect on losses, their interaction with a fragmented landscape makes conflicts more unpredictable. In contrast, better-connected landscapes facilitate access to wild prey, reducing attacks on livestock. Similarly, König et al. (2023) in Germany identify landscape configurations with increased predation risk. The combination of meadows, forests, and cultivated lands plays a key role, highlighting the importance of habitat structure in large carnivore management.

Furthermore, in India, Frank et al. (2021) highlight a significant dietary overlap between wild ungulate species (blackbuck, chital), domestic livestock, and feral horses. The latter are favored by habitat fragmentation and overlapping land uses (pastoralism, wildlife, introduced animals), thereby threatening the long-term viability of specialized wild ungulate populations, particularly during the dry season.

Puri et al. (2022), in the Kanha-Pench Forest corridor (central India), also demonstrate how habitat fragmentation poses a risk to tiger conservation. By limiting connectivity between forest cores, it restricts the species’ movements and increases the likelihood of encounters with livestock. Areas under intense human pressure can become ecological traps, where herders face heightened risks of livestock predation while tigers face increased retaliation, thereby compromising long-term conservation efforts.

Habitat fragmentation thus appears as a factor weakening the structuring of interfaces. These findings highlight the importance of integrating not only the spatial configuration of the territory but also the pastoral practices that shape them into strategies for coexistence between livestock and wildlife.

Societal changes: an additional pressure exacerbating social inequalities

Societal changes reflect broader socio-economic transformations such as wildlife conservation policies, the globalization of sanitary standards, and the internationalization of trade. These changes act as additional pressures experienced by pastoral livestock systems. Olson and Goethlich (2024) particularly highlight that institutional commitment to large carnivore conservation can generate tensions when perceived as unbalanced in resource access or marginalizing local knowledge. Conservation policies viewed as distant, and authoritarian may indeed provoke feelings of powerlessness and frustration among herders, leading to intolerance toward wildlife and, in some cases, illegal actions such as poaching. Treves et al. (2009) as well as Gadaga et al. (2015) further note that the costs of wildlife conservation are unevenly distributed within societies, exacerbating social tensions and inequalities. These changes profoundly transform the interface between human populations, livestock, and natural environments. They amplify health, ecological, and economic risks while intensifying conflicts with herders over the formulation of policies that affect them.

Climate risk: a cross-cutting aggravating factor

Climate risk exacerbates the hazards associated with the physical interface between wildlife and pastoral livestock systems. According to Abrahms et al. (2023), climate change effects, such as altered precipitation patterns and rising temperatures, intensify the risks of competition for water resources. Similarly, Titcomb G. et al. (2021) underline a direct link between increased droughts and the concentration of animals around the few available water points.

This proximity particularly facilitates pathogen transmission between wildlife and livestock, thereby increasing health risks (Barasona et al., 2013). Climate change also alters parasitic transmission dynamics related to host density, microclimates, and livestock practices. Increased seasonal grazing could further expose wild species, underscoring the need to integrate host movements into climate-related health projections (Dickinson et al., 2024). Similarly, the systematic review by Becvarik et al. (2023) confirms temperature as a key factor influencing the distribution of zoonoses. The authors particularly advocate for a One Health approach to anticipate and manage the risk of introducing new zoonoses linked to rising temperatures. Finally, climate and landscape characteristics at the micro-habitat scale directly affect the abundance and activity of certain parasites, thereby influencing the transmission of pathogens of medical and veterinary importance (Knap et al., 2009).

The concentration of animals during periods of thermal or water stress, for example, near water points, creates hotspots favorable to predation (Connolly et al., 2021). According to Vargas et al. (2022), the combined effects of climate change, particularly mega-droughts, and ecological pressure exacerbate conflicts between wildlife (puma, condor, guanaco) and transhumant herders. Boone et al. (2024) highlight increased household vulnerability due to the combined effects of climate change. They demonstrate how recurrent droughts lead to livestock losses, increased pressure on resources, and the gradual collapse of resilience mechanisms.

Killion et al. (2021) emphasize finally the limitations of adaptation strategies as extreme climatic events become more frequent. Morales-Reyes et al. (2025) found the exhaustion of adaptive strategies such as diversification or migration, alongside increasing debt and food insecurity. The experience of herders is central: many feels “trapped” in an increasingly unstable system where adaptation options are shrinking.

Climate change thus acts as a risk multiplier. It is therefore essential to integrate it as a cross-cutting factor in the analysis of conflicts and vulnerabilities at the studied interfaces.

Discussion

At this stage, this discussion aims to interpret and contextualize the results obtained by examining them through several complementary perspectives. It first considers risk as an interdisciplinary concept, before exploring the notion of multiple and interconnected risks, as well as the multidimensional nature of the complex interface between wildlife and pastoral livestock system. The discussion then addresses the contested legitimacy of pastoralism and the degradation of human–nature relationships, which highlight the tensions and challenges associated with the coexistence of social and ecological dynamics. The discussion leads finally to a reflection on the need for a more integrated approach to risk management.

Risk as an interdisciplinary concept

The diversity of risk categories identified in this work reflects the interdisciplinary nature of the pressures weighting livestock farming systems and questions how the concept of risk is understood through literature.

In ecological and biophysical approaches, risk is generally defined as the probability of a damaging event and the severity of its consequences on a given system (Blaikie, 1994; Adger, 2006; IPCC et al., 2014). In pastoral systems, this encompasses droughts, epizootics, predation, or pasture degradation: risks perceived as external threats that can be mitigated through prevention, monitoring, or technical adjustments.

Socio-economic approaches shift the focus toward the vulnerability of livelihoods and households’ capacity to cope with uncertainty (Ellis and Swift, 1988). Here, risk emerges from the combination of external hazards and internal fragilities, market dependency, unequal resource access, institutional constraints, and is understood as a socially embedded process shaped by inequalities and political choices as much as by environmental hazards.

Psychosocial and cultural approaches emphasize the subjective and interpretive nature of risk. As shown by Douglas and Wildavsky (1987) and Slovic (1987), risk is not only an objective danger but also a socially mediated construct, interpreted and prioritized according to values, experiences, and cultural frames. In pastoral contexts, perceptions of threats, predators, diseases, environmental changes, depend on collective representations of wildlife, memories of past conflicts, and trust in institutions.

Finally, some systemic and integrated approaches conceptualize risk as an emergent property of socio-ecological systems (Folke et al., 2010; Cutter et al., 2008). In this way, situated at the crossroads of biological, ecological, economic and social sciences, the varied uses of the notion of risk in the literature highlight that it should be understood as an interdisciplinary construction resulting from complex dynamics embedded in global change contexts. This plurality of meanings provides a conceptual foundation for better understanding how multiple and interconnected risks operate at the wildlife–pastoral livestock system interface.

Multiple, interconnected and shared risks at the multidimensional wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface

Through the three major types of risks at the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface identified in this study, risks appear as multiple and diverse, stemming from biological and ecological, socio-economic, and amplifying factors. They are neither independent nor linear; rather, they interact, reinforce each other, and evolve depending on the context.

For example, climate risk leads to reduced water resources, increasing competition between wildlife and livestock for these resources (Abrahms et al., 2023). This increased competition can heighten predation risk for herds (Connolly et al., 2021). Financial losses linked to livestock predation exacerbate economic pressures (Aryal et al., 2014; Muriuki et al., 2017) and may intensify poaching and resentment towards institutions (Muriuki et al., 2017; Mwangi et al., 2016). Recurrent droughts deplete the adaptive capacities of herders, such as mobility, mutual support, and diversification, and make them more vulnerable to combined risks (diseases, resource conflicts, economic losses) (Killion et al., 2021; Boone et al., 2024). These pressures can consequently exacerbate social inequalities at multiple levels, as difficulties in accessing knowledge and healthcare, along with cultural practices, amplify vulnerabilities. Similarly, the differential risk of exposure to pathogens contributes to reinforcing gender inequalities by placing a disproportionate health burden on women or men depending on social roles (Coyle et al., 2020). Such cascading interactions correspond to what we define as systemic amplifying risks, where ecological, socio-economic, and institutional processes reinforce each other. These interconnections echo global observations on rangeland systems, where climate, health, and governance risks increasingly converge (Reid et al., 2014; Folke et al., 2010). At the same time, wildlife populations are also exposed to many of the same risks identified in our analytical framework, reflecting the strong ecological interdependence with domestic herbivores within shared landscapes. Indeed, they face biological and ecological risks such as parasitism, zoonotic transmission, predation and competition for forage and water (Keesing et al., 2018; Katale et al., 2013; Mbizeni et al., 2013; Connolly et al., 2021; Martinez et al., 2024). They are also affected by habitat fragmentation and climatic variability (Puri et al., 2022; Barasona et al., 2013; Abrahms et al., 2023). This parallel exposure highlights that the dynamics of risk are collective rather than isolated, linking the vulnerabilities of wildlife and pastoral systems are closely interdependent within the same socio-ecological landscapes.

While the literature confirms that causal links between risks can occur, their form, intensity, and even their presence vary according to local contexts. In some situations, the chain of interactions may be shorter or longer, stronger or weaker, or even absent for certain components. This variability underlines the need for adaptive, context-specific management approaches that consider the singularities of each territory, and sometimes even of each community, rather than assuming a uniform and universal cascade of effects. These multiple pressures, modulated by numerous local factors, contribute to systemic vulnerability, where resilience capacities are continuously challenged for both pastoral systems and wildlife (Du Toit et al., 2017). These cascading effects, where one risk amplifies or triggers another, are particularly relevant in pastoral contexts marked by strong interdependence between ecological, economic, and social dimensions. Further exploring these chain reactions offers a valuable lens to understand how localized disturbances (e.g., predator attacks, disease outbreaks, loss of access to grazing areas) can lead to broader disruptions in livelihoods, land use, and territorial cohesion.

Similarly, the diversity of situations described in the literature shows that the interface between wildlife and pastoral livestock does not constitute a homogeneous space, but rather a complex, evolving socio-ecological system where health, ecological, social, economic, and political dimensions interact. Conflicts that emerge at this interface result as much from socio-economic factors (crop losses, livelihood insecurity) as from cultural and environmental values (fears, frustrations towards wildlife) (Yeshey et al., 2024). Health concerns, even in the absence of confirmed transmission, alter herders’ practices: routes to water points, grazing schedules, and herd monitoring (Benka, 2023). These adjustments reflect an interface shaped by perceived risk, emotions (frustration, anxiety), and coexistence with diverse species, confirming that human–wildlife dynamics involve relational as much as biological logics (Cozza et al., 1996). Linking ecological dynamics (fragmentation, corridors) to human dimensions (beliefs, attitudes) allows a better understanding of the complexity of this interface (Teixeira et al., 2021). This multidimensional perspective supports the proposed analytical framework to better understand the dynamics at the wildlife–pastoral livestock systems interface. Recognizing it as a multifaceted, evolving reality, rather than a static conflict zone, is key to designing adaptive and inclusive management strategies that operate at both local and global scales. Furthermore, developing more framework for risk analysis at this interface is therefore essential to capture these interdependencies and to understand how ecological, health, and socio-economic processes interact to shape the resilience of both pastoral and wildlife systems.

Pastoralism portrayed as a risk: a contested legitimacy in conservation arenas

Beyond the interdisciplinary, multiple, and interconnected nature of risks, or of the complex interface between wildlife and pastoral livestock systems, pastoral systems continue to be portrayed as problematic within conservation discourses, even though for their ecological and socio-economic value is increasingly recognized.

For decades, conflicts between livestock and wildlife have shaped both scientific and policy discourses, often leading to misguided interventions. Early conservation narratives framed pastoralism as inherently incompatible with wildlife conservation, rooted in equilibrium-based ecological models that associated livestock with overgrazing, competition for essential resources, and biodiversity loss (Prins, 2000; Homewood, 2008). Within this logic, pastoralists were considered as direct competitors with wildlife or as agents of rangeland degradation, whose practices threaten biodiversity conservation goals (Homewood, 2008; Niamir-Fuller et al., 2012; Prins, 2000). In southern Africa, for instance, the competition and disease risks between livestock and wildlife justified large-scale fencing policies in Botswana and Namibia. These measures, intended to protect wildlife and control diseases such as foot-and-mouth, fragmented migration corridors and resulted in massive wildlife mortality (Perkins, 1996; Twyman, 2000). In the Indian Himalaya, Singh et al. (2022) highlights how rangeland conservation policies have led to the displacement of herders and the erosion of traditional resource management institutions. Likewise, Gooch (2009) describes how the exclusion of herders from protected areas in Central Asia has undermined both social equity and landscape resilience. Such examples illustrate how the portrayal of pastoralism as ecologically harmful led to exclusionary and ecologically counterproductive outcomes. These representations are rooted in historical approaches to conservation that sought to separate people from nature, following the “fortress conservation” model that legitimized the exclusion of local populations from protected areas (Igoe and Brockington, 2002; Duffy, 2014). This framing has contributed to persistent tensions between conservation and pastoral livelihoods: access restrictions, grazing bans, and competing land-use priorities have often reinforced the marginalization of pastoral communities and constrained their mobility, which is a key adaptive strategy in variable environments (Brockington and Igoe, 2006; Goldman, 2020). As a result, the coexistence between pastoralists and wildlife has been shaped as much by ecological dynamics as by political and institutional relations that define whose presence in rangelands is considered legitimate (Reid et al., 2014; Homewood, 2008).

However, the narrative of incompatibility between livestock and wildlife has been increasingly challenged since the 1990s. A growing body of research in rangeland ecology and conservation science has demonstrated that these ecosystems are governed by climatic variability rather than grazing pressure, and that mobile pastoralism can contribute to maintaining vegetation diversity, open habitats, and ecological connectivity (Ellis and Swift, 1988; Behnke et al., 1994; Reid et al., 2014). More recent studies underline a gradual shift toward more inclusive conservation models that acknowledge the contribution of pastoral knowledge and mobility to rangeland biodiversity (Behnke and Mortimore, 2016; Fernández-Giménez et al., 2015; Fernández-Giménez, 2015). Empirical cases now show that extensive pastoral systems and wildlife can coexist, sometimes even benefiting each other through processes such as habitat maintenance, nutrient cycling, and disease and parasite regulation (Augustine, 2010; Keesing et al., 2013).

Initiatives based on community participation and integrated landscape approaches increasingly demonstrate that coexistence is not only possible but also essential to the resilience of both pastoral and wildlife systems (Niamir-Fuller et al., 2012; Reid et al., 2014). From this perspective, risk can also be understood as a political and discursive construct: pastoralism itself has been portrayed as a risk, legitimizing exclusionary conservation regimes. No longer questioning the legitimacy of both pastoralism and conservation within the wildlife-pastoral livestock system interface would open the way for a more constructive reflection on the conditions for a sustainable and compatible coexistence.

The degradation of human-nature relationships as an invisible risk

This work also reveals another transversal and systemic risk, one that is omnipresent, silent and critical: the deterioration of the relationships between human societies and nature.

Coexistence, in this sense, is not merely as a constraint or a specific type of risk, but as an expression of a way of life and a worldview (Laverty et al., 2019). The cultural ties to nature within pastoral societies reveal how the erosion of these coexistence logics gradually destabilizes the social balance that has historically sustained (Laverty et al., 2019).