Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the potential risk of bullous pemphigoid (BP) in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and to characterize ICI-related BP (irBP) using the United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database.

Methods:

The present study conducted a disproportionality analysis leveraging FAERS database, spanning the first quarter (Q1) of 2004–2025 Q1. To ensure robust signal detection, we employed a quadruple analytical approach incorporating: (1) reporting odds ratio (ROR), (2) proportional reporting ratio, (3) Bayesian confidence propagation neural network, and (4) multi-item gamma Poisson shrinker algorithms. These methodologies were systematically applied to assess the potential risk of BP in patients treated with ICIs. Furthermore, temporal characteristics of adverse event emergence were quantitatively assessed to delineate the time-to-onset patterns.

Results:

There are 850 irBP cases identified, comprising reports associated with the following agents: nivolumab (n = 530), pembrolizumab (n = 180), ipilimumab (n = 44), atezolizumab (n = 40), cemiplimab (n = 24), durvalumab (n = 19), tislelizumab (n = 10), and avelumab (n = 3). Affected patients were predominantly males (67.8%) and over 60 years of age (70.1%). All eight ICIs showed positive disproportionality signals, with ROR values ranked descendingly as: cemiplimab > nivolumab > tislelizumab > pembrolizumab > ipilimumab > durvalumab > atezolizumab > avelumab. The median time of irBP onset was 165.2 (IQR: 56–410) days.

Conclusion:

The study establishes a significant link between ICIs and BP. All ICIs increase BP risk. CTLA-4 inhibitors exhibited the most marked early risk concentration, highlighting the importance of early dermatologic evaluation after initiating CTLA-4 blockade.

Introduction

Recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been developed as novel therapeutic agents for malignancies, achieving significant anti-tumor responses and extending survival in patients with certain tumor groups [1]. ICIs encompass monoclonal antibodies that target programmed cell death-1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4). Their anti-cancer effect is mediated by selectively blocking these key immune regulatory pathways, thereby releasing T cell to recognize and destroy tumor antigens [1]. However, this enhancement of anti-tumor immunity can paradoxically lead to nonspecific immune system activation, resulting in a group of toxicities collectively termed immune-related adverse events (irAEs) [2].

Cutaneous irAEs (cirAEs) are the most common irAEs, with a reported incidence approaching 30% in patients treated with ICIs [3]. While the most common cirAEs include nonspecific rash or pruritus, diseases such as eczema, psoriasis and vitiligo are also observed [4]. The mechanism of cirAEs may include epitope spreading and altered T cell subsets [5–7]. Although emerging evidence suggests that cirAEs are associated with enhanced anti-tumor response and improved patient survival outcomes in patients receiving ICIs [8]. CirAEs frequently compromise patients’ quality of life and potentially necessitate discontinuation of ICIs therapy. Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is a subepidermal autoimmune blistering disease and it may also occur from ICIs therapy (ICI-related BP, irBP). ICIs targeting the PD-L1/PD-1 axis can elicit BP in about 0.3%–0.6% patients [9]. In a cohort study of 5636 patients treated with ICIs, 35 (0.6%) developed BP [10]. Notably, irBP patients exhibits distinct clinical features compared to classical BP, such as a prolonged pruritic prodromal phases and extended corticosteroids treatment requirements [3]. Current understanding of irBP remains limited due to small sample sizes in existing studies, and the low prevalence of this condition continues to pose significant challenges in comprehensive clinical characterization.

The US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) is a publicly available database that aggregates voluntary reports of drug-associated AEs from health-care professionals and patients globally. Existing studies on irBP demonstrates notable limitations: (1) The work by Aggarwal et al. [11] while establishing FAERS as a viable data source, was constrained to PD-1 inhibitors (pembrolizumab and nivolumab), with modest case numbers (n = 118). (2) Tan et al. ’s comprehensive FAERS-based study (2011 Q1–2024 Q1), despite employing reporting odds ratio (ROR) methodology across 13-year data, exhibited three key constraints: (a) exclusive reliance on a single disproportionality analysis without complementary method, (b) lack of intra-class agent differentiation, (3) absence of temporal risk quantification.

This study provides a comprehensive pharmacovigilance analysis of irBP by leveraging the FAERS database over an extended period (Q1 2004–Q1 2025). We employed a multi-methodological approach for both signal detection and temporal risk assessment, which included the reporting odds ratio (ROR), proportional reporting ratio (PRR), Bayesian confidence propagation neural network (BCPNN), and multi-item gamma Poisson shrinker (MGPS). By integrating four complementary disproportionality algorithms, we enhanced the robustness and reliability of signal identification. Moreover, we integrated Kaplan–Meier analysis with Weibull shape parameter (WSP) modeling to quantitatively delineate temporal risk patterns. A key advancement in our study was the extension of evaluation beyond the ICI class level to encompass individual agent-level analyses, allowing direct comparisons of clinical characteristics and signal strengths among agents within the same class. Notably, disproportionality analyses consistently showed that PD-1 inhibitors exhibited a higher ROR for irBP compared to CTLA-4 inhibitors, which in turn showed higher ROR values than PD-L1 inhibitors. Collectively, these methodological refinements significantly enhance the depth and breadth of data analysis, providing a solid evidence base for more precise identification and understanding of irBP risk. This, in turn, facilitates the optimization of clinical monitoring and preventive strategies.

Methods

Data mining

This retrospective disproportionality analysis utilized FAERS database, accessed from1. The study period spanned from the first quarter (Q1) of 2004 to Q1 of 2025. As the study involved analysis of publicly available, anonymized secondary data, it did not require institutional review board approval or direct involvement of human subjects.

The FAERS database includes seven core datasets: demographics (DEMO), drug (DRUG), adverse events (REAC), outcomes (OUTC), report source (RPSR), therapy date (THER), and drug indications (INDI). Reports were included if they listed an ICIs as the primary suspected drug (role_cod = PS). The included ICIs was:

PD-1 inhibitors: nivolumab, pembrolizumab, cemiplimab, dostarlimab, tislelizumab

PD-L1 inhibitors: atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab

CTLA-4 inhibitors: ipilimumab, tremelimumab.

Therapy regimens were defined as:

ICI monotherapy: Sole use of one ICI designated as the primary suspected drug.

ICIs combination therapy: Concurrent use of two or more ICIs, with at least one designated as primary suspected drug.

AEs of interest were defined by the MedDRA preferred terms categorized under the standardized MedDRA query for “pemphigoid.”

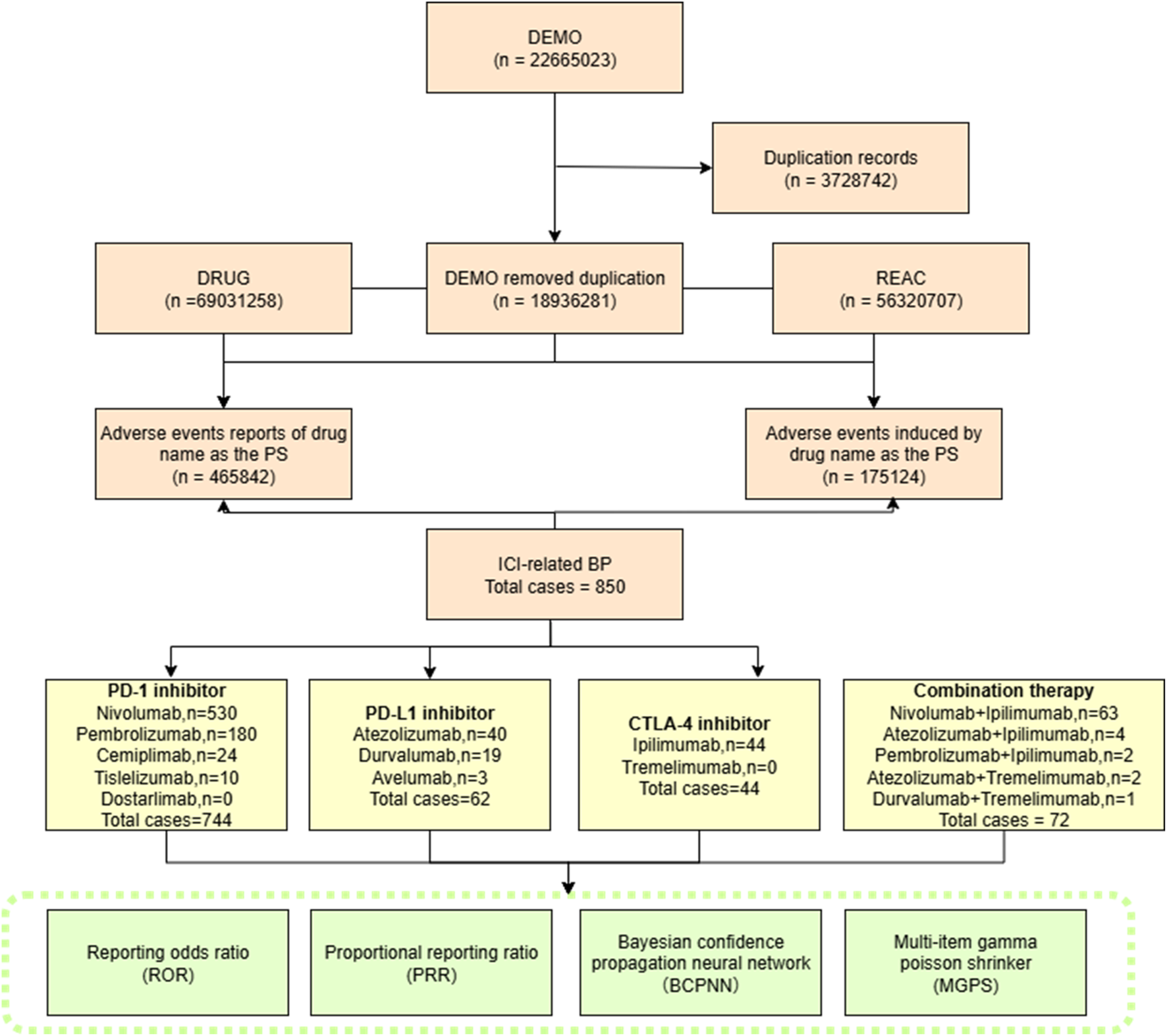

Duplicate reports were removed following FDA’s official guidance: (1) for reports with the same CASEID, only the record with the latest FDA_DT was retained; (2) if both CASEID and FDA_DT were identical, the record with the highest PRIMARYID was included. Subsequently, data of clinical characteristics were collected: gender, age, indications, outcomes, reporters and report countries. A flow diagram of the process is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Flow chart showing the selection process of irBP in the FAERS database.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the association between ICIs and BP, four complementary signal detection methods are employed: (1) ROR; (2) PRR; (3) BCPNN: measured via information component (IC); (4) MGPS: estimated via empirical Bayes geometric mean (EBGM). Each method compared the frequency of BP reports with ICI exposure to other AE reports in the FAERS database. Positive signals were defined based on established criteria for each method: (1) ROR >1 with a lower 95% confidence interval (CI) >1 and at least three reports (a ≥ 3); (2) PRR ≥2 with a chi-squared (χ2) statistic ≥ 4 and a ≥ 3; (3) IC025 >0 for BCPNN; and (4) EBGM05 >2 for MGPS (Supplementary Table S1).

Time-to-onset (TTO) was defined as the temporal span between the commencement of ICIs and the onset of BP. To uphold the precision, records featuring erroneous date entries, discrepancies, and omissions were ruled out. TTO was analyzed using descriptive statistics and modeled using the WSP to characterize hazard patterns over time. The Kaplan-Meier method was also utilized to evaluate TTO.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.22), and data visualizations were performed using Python (version 3.12). A two-sided p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive characteristics: pemphigoid

Within the FAERS database, 850 irBP cases were identified, in which 744 cases (87.5%) were induced by PD-1 inhibitors, 62 (7.3%) by PD-L1 inhibitors, and 44 (5.2%) by CTLA-4 inhibitors. Seventy-two cases were induced by ICIs combination therapy. The clinical characteristics were detailed in Table 1; Figure 2.

TABLE 1

| Characteristics | All ICIs | PD-1i | PD-L1i | CTLA-4i |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 576 | 507 | 35 | 34 |

| Female | 187 | 161 | 18 | 8 |

| Unspecified | 87 | 76 | 9 | 2 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Median | 71 | 71 | 76 | 71 |

| <18 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 18–60 | 105 | 94 | 2 | 9 |

| >60 | 596 | 523 | 45 | 28 |

| Missing | 148 | 126 | 15 | 7 |

| Top 3 reported countries | ||||

| | JP 250 | US 209 | JP 16 | JP 26 |

| | US 227 | JP 208 | US 13 | FR 8 |

| | FR 138 | FR 119 | FR11 | US 5 |

| Reporter’s occupation | ||||

| Healthcare professional | 736 | 680 | 62 | 43 |

| Non-healthcare professional | 112 | 62 | - | 1 |

| Missing | 2 | 2 | - | - |

| Top 5 indication | ||||

| MM (209) | MM (191) | HC (12) | MM (18) | |

| NSCLC (67) | NSCLC (61) | SCLC (5) | RCC (8) | |

| Metastatic RCC (43) | Metastatic RCC (38) | NSCLC (5) | Pleural mesothelioma malignant (3) | |

| Unknown (40) | Unknown (37) | SCC (5) | NSCLC recurrent (2) | |

| GC (35) | GC (35) | Bladder transitional cell carcinoma (4) | Unknown (3) | |

| Outcome | ||||

| Hospitalization | 307 | 266 | 23 | 18 |

| Life-threatening | 24 | 222 | 2 | - |

| Disability | 14 | 14 | - | - |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 15 | - |

| Death | 51 | 44 | 6 | 1 |

| Other | 816 | 727 | 16 | 25 |

Clinical characteristics of ICIs-BP from the FAERS database (Q1 2004–Q1 2025).

CTLA-4i, CTLA-4, inhibitor; PD-L1i, PD-L1, inhibitor; PD-1i, PD-1, inhibitor; JP, japan; US, the United States; FR, France; MM, malignant melanoma; NSCLC, Non-small cell lung cancer; HC, hepatocellular carcinoma; SCC, small cell lung cancer; RC, renal cell carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; GC, gastric cancer.

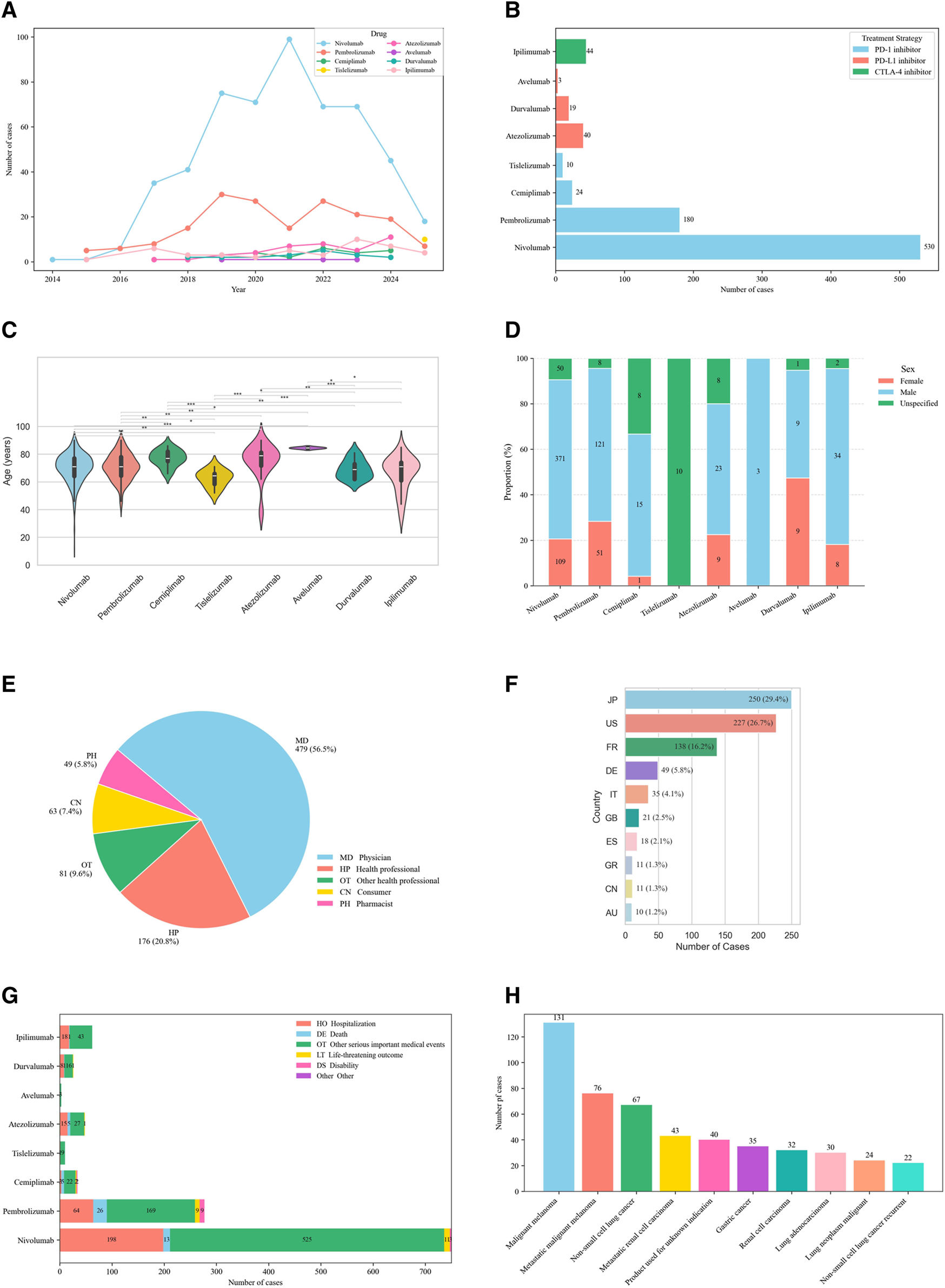

FIGURE 2

Demographic characteristics of irBP from the FAERS database (Q1 2004–Q1 2025). (A) Distribution of reported irBP by years. (B) Distribution of cases number by treatment strategy. (C) Distribution of patient’s age. Statistical tests were conducted using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. (**p < 0.01,***p < 0.001,****p < 0.0001). (D) Distribution of patient’s gender. (E) Distribution of reporters. (F) Distribution of cases reported by the top ten countries. (G) Distribution of patients’ outcome. (H) Distribution of cancer types among patients.

The cohort was predominantly males (576 cases, 67.8%) versus females (187 cases, 22.0%), with sex unspecified in 87 cases (10.2%). Median patient age was 71 years, with most cases occurring in patients >60 years (596, 70.1%) compared to 18–60 year-olds (105, 12.4%). Geographically, Japan reported the highest number of cases (250, 29.4%), followed by the United States (227, 26.7%) and France (138, 16.2%). Reports originated primarily healthcare professional (736, 86.6%) versus non-healthcare professional (112, 13.2%).

Among 850 irBP cases, most occurred in patients treated for skin and melanoma-related malignancies (260 cases, 30.6%; mainly malignant melanoma, 131 cases), followed by lung cancers (192, 22.6%; mainly non-small cell lung cancer, 67 cases, and lung adenocarcinoma, 30 cases), renal and urinary tract tumors (149, 17.5%; including metastatic renal cell carcinoma, 43 cases, renal cell carcinoma, 32 cases, and bladder/urinary tract tumors, 27 cases), gastrointestinal malignancies (51, 6.0%; mainly gastric and esophageal cancer), head and neck cancers (33, 3.9%), liver malignancies (20, 2.4%), and other or unclassified indications (109, 12.8%). Regarding outcomes, hospitalization was most common (307, 36.1%), followed by life-threatening events (24, 2.8%) and disability (14, 1.65%).

Disproportionality analysis (signal detection)

Significant pharmacovigilance signals for BP were detected across all eight ICIs analyzed. Significant associations were confirmed for each ICI class:

PD-1 inhibitor (ROR = 22.66, 95% CI 20.99–24.47)

CTLA-4 inhibitor (ROR = 8.79, 95% CI 6.53–11.83)

PD-L1 inhibitor (ROR = 6.55, 95% CI 5.10–8.41)

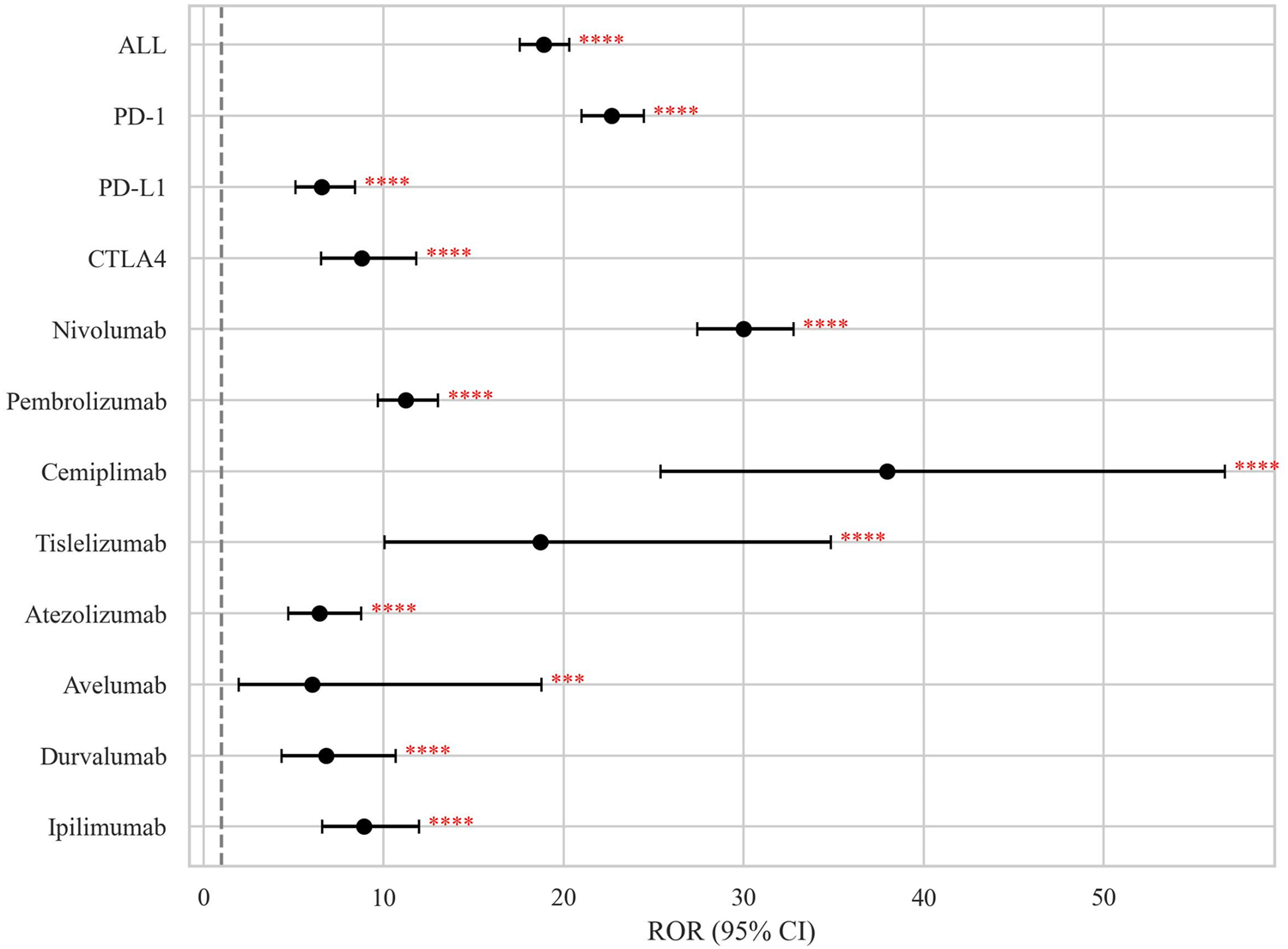

At the individual agent level, cemiplimab demonstrated the strongest association (ROR = 37.96, 95% CI 25.40–56.73), followed by nivolumab (ROR = 29.99, 95% CI 27.43–32.78) and tislelizumab (ROR = 18.72, 95% CI 10.06–34.84) (Figure 3; Table 2).

FIGURE 3

Disproportionality signals of ICIs related BP in the FAERS database. The dashed line indicates that ROR = 1.NS, no significance; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

TABLE 2

| Treatment | Number of cases | ROR (95% CI) | PRR (χ2) | MGPS(EBGM05) | BCPNN (IC025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ICIs | 850 | 18.90 (17.58–20.31) | 18.86 (12,425.30) | 16.43 (15.29) | 4.04 (3.9) |

| PD-1i | 744 | 22.66 (20.99–24.47) | 22.61 (13,542.03) | 20.04 (18.56) | 4.32 (4.2) |

| Nivolumab | 530 | 29.99 (27.43–32.78) | 29.90 (13,550.60) | 27.45 (25.11) | 4.78 (4.6) |

| Pembrolizumab | 180 | 11.24 (9.69–13.04) | 11.23 (1,629.07) | 10.93 (9.43) | 3.45 (3.2) |

| Cemiplimab | 24 | 37.96 (25.40–56.73) | 37.81 (856.81) | 37.67 (25.21) | 5.24 (3.4) |

| Tislelizumab | 10 | 18.72 (10.06–34.84) | 18.69 (167.16) | 18.66 (10.03) | 4.22 (2.0) |

| Dostarlimab | - | - | - | - | - |

| PD-L1i | 62 | 6.55 (5.10–8.41) | 6.54 (288.20) | 6.49 (5.05) | 2.70 (2.2) |

| Atezolizumab | 40 | 6.43 (4.71–8.77) | 6.42 (181.95) | 6.39 (4.68) | 2.68 (2.0) |

| Durvalumab | 19 | 6.81 (4.34–10.68) | 6.80 (93.80) | 6.79 (4.33) | 2.76 (1.7) |

| Avelumab | 3 | 6.05 (1.95–18.78) | 6.05 (12.64) | 6.05 (1.95) | 2.60 (−0.1) |

| CTLA-4i | 44 | 8.79 (6.53–11.83) | 8.78 (301.33) | 8.73 (6.49) | 3.13 (2.5) |

| Ipilimumab | 44 | 8.79 (6.53–11.83) | 8.78 (301.33) | 8.73 (6.49) | 3.13 (2.5) |

| Tremelimumab | - | - | - | - | - |

| Combination therapy | |||||

| Novi + Ipi | 63 | 12.71 (9.92–16.30) | 12.70 (672.19) | 12.58 (9.81) | 3.65 (3.1) |

| Ate + Ipi | 4 | 24.14 (9.05–64.43) | 24.08 (88.45) | 24.07 (9.02) | 4.59 (0.8) |

| Prem + Ipi(False) | 2 | 14.80 (3.70–59.28) | 14.78 (25.69) | 14.78 (3.69) | 3.89 (−0.3) |

| Dur + Tre(False) | 1 | 2.48 (0.35–17.61) | 2.48 (0.88) | 2.48 (0.35) | 1.31 (−1.5) |

| Ate + Tre(False) | 2 | 35.96 (8.97–144.23) | 35.82 (67.69) | 35.81 (8.93) | 5.16 (−0.2) |

Disproportionality analysis of irBP.

CTLA-4i, CTLA-4, inhibitor; PD-L1i, PD-L1, inhibitor; PD-1i, PD-1, inhibitor; ROR, reporting odds ratio (ROR >1, 95% CI >1, N ≥3); CI, confidence interval; PRR, proportional reporting ratio (PRR ≥2, χ2 ≥ 4, N ≥ 3); MGPS, multi-item gamma Poisson shrinker (EBGM05 >2); EBGM, empirical Bayesian geometric mean; EBGM05, lower limit of the one-sided 95% CI, of EBGM; BCPNN, Bayesian confidence propagation neural network (IC025 >0). “False” indicates that N < 3, without positive signal formation.

Time-to-onset (TTO) analysis and temporal risk pattern analysis

Valid TTO data were available for 249 AE reports (29.29%). The median onset time to irBP was 165.2 days (IQR: 56–410). When stratified by ICI class, the median TTO differed significantly:

PD-1 inhibitor-related BP: 190.5 days, (IQR: 62–425)

PD-L1 inhibitor-related BP: 81 days, (IQR: 13.5–242.2)

CTLA-4 inhibitor-related BP: 35.7 days, (IQR: 9–84).

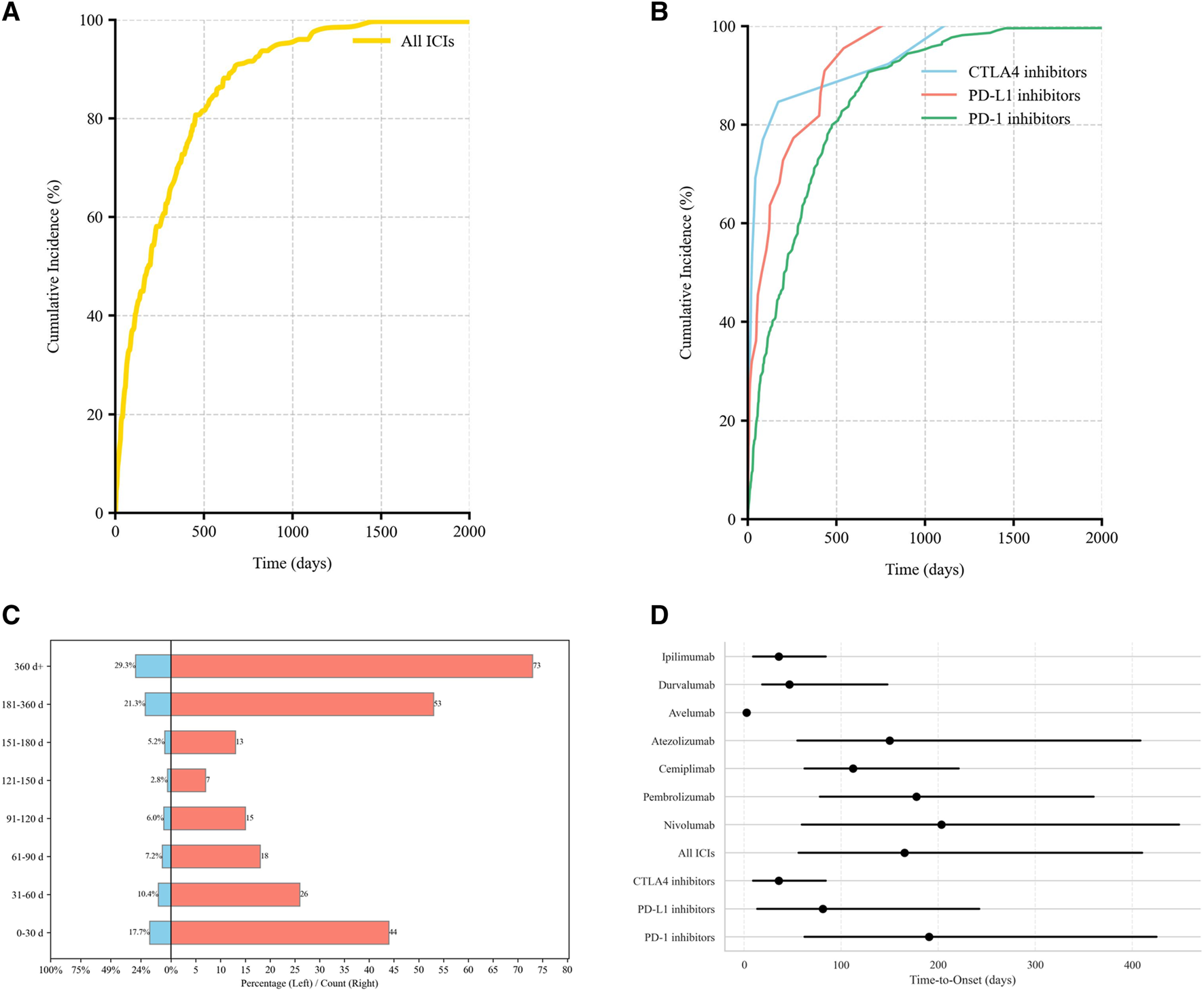

The cumulative incidence curves showed that 17.7% of BP cases occurred within the first month of treatment, while 50.6% occurred after 6 months of therapy (Figure 4). Notably, PD-1 inhibitors demonstrated a significantly higher cumulative incidence rate over time compared to CTLA-4 inhibitors (adjusted p = 0.014; Table 3).

FIGURE 4

Time-to-onset (TTO) distribution of irBP. (A) The cumulative distribution curves for irBP. (B) The cumulative distribution curves for three ICIs. (C) Distribution of TTO. (D) The TTO for each drug.

TABLE 3

| Group 1 | Group 2 | U statistic | Raw p-value | Adjusted p-value (Bonferroni) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ICIs | CTLA-4i | 2350.5 | 0.006025 | 0.036148 | Significant (p < 0.05) |

| All ICIs | PD-L1i | 3,410.5 | 0.056873 | 0.34124 | NS |

| All ICIs | PD-1i | 25,239.5 | 0.328347 | 1 | NS |

| CTLA-4i | PD-L1i | 108 | 0.238675 | 1 | NS |

| CTLA-4i | PD-1i | 694 | 0.002449 | 0.014696 | Significant (p < 0.05) |

| PD-L1i | PD-1i | 1,647.5 | 0.020595 | 0.123572 | NS |

Mann-Whitney U test for time-to-onset of ICIs-related BP.

NS., not significant; CTLA-4i, CTLA-4, inhibitor; PD-L1i, PD-L1, inhibitor; PD-1i, PD-1, inhibitor.

To further characterize temporal risk pattern of BP onset, we applied the WSP model. All ICI categories demonstrated a shape parameter β < 1, indicating an early failure type where the risk of BP onset peaks shortly after treatment initiation and subsequently decreases.

Significant inter-class differences emerged:

CTLA-4 inhibitors showed a sharply concentrated early-onset risk window (β = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.41–0.91).

PD-L1 inhibitors exhibited intermediate risk concentration (β = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.56, 0.95)

PD-1 inhibitors displayed the broadest early-onset patterns (β = 0.83, 95% CI:0.72, 0.98) (Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Drug | Cases (n) | TTO (days) | Weibull shape parameter | Failure type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Min–max | α (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | |||

| PD-1i | 214 | 190.5 (62–425) | 1–7426 | 295.85 (252.96, 345.92) | 0.83 (0.72, 0.98) | Early |

| PD-L1i | 22 | 81 (13.5–242.2) | 2–756 | 137.83 (69.24, 223.69) | 0.69 (0.56, 0.95) | Early |

| CTLA-4i | 13 | 35.7 (9–84) | 1–1,108 | 76.24 (21.45, 195.16) | 0.48 (0.41, 0.91) | Early |

| All ICIs | 249 | 165.2 (56–410) | 1–7426 | 264.3 (231.92, 313.6) | 0.78 (0.69, 0.92) | Early |

Weibull shape parameter test for ICIs-related BP.

α = scale parameter; β = shape parameter. β < 1 indicates an early failure pattern.

The scale parameter α, representing the spread of TTO distribution, was highest with PD-1 inhibitor (α = 295.85), consistent with prolonged and variable onset. CTLA-4 inhibitors had the lowest α (76.24), supporting a tightly clustered onset pattern.

Discussion

The increasing application of ICIs has significantly improved oncological outcomes, but various irAEs have also been reported. In particular, BP represents a rare but potentially serious cirAE, with this study identifying 51% mortality and 24% life-threatening outcomes among affected patients. Importantly, considering that ICIs are indicated for high mortality diseases, the primary cause of death and other detrimental outcomes may be attributed to disease progression rather than direct treatment toxicity.

In the current study, we provided a comprehensive pharmacovigilance analysis of irBP encompassing 850 documented cases. Consistent with previous findings [12], irBP occurred more commonly in males (67.8%) than females (22.0%). However, the global incidence rates of classical BP reveal a slightly higher rate in females (0.0202 per 1,000 person-years) compared to males (0.0181 per 1,000 person-years) [13]. This discrepancy may be attributed to the male predominance of certain types of cancer, such as melanoma, lung cancer, and renal cell carcinoma, which are major indications for ICIs [14–16]. The utilization patterns of ICIs in Korea also showed that the proportion of males (76.3%) was higher than that of females [17]. The most common age group was over 60 years (70.1%), which is consistent with the global incidence for different age groups [13]. Geographically, Japan accounted for the largest share of reports (29.4%), followed by the United States (26.7%) and France (16.2%). Notably, genetic polymorphism increases the risk of irBP [18], while ethnic differences play a role in genetic susceptibility to BP [19], which may also be the case in irBP.

Among irBP cases treated with ICIs, the majority occurred in patients treated for skin/melanoma (30.6%, mainly malignant melanoma), lung (22.6%, mainly non-small cell lung cancer), and kidney/renal malignancies (14.4%, mainly metastatic renal cell carcinoma), with smaller proportions in gastrointestinal, head and neck, bladder/urinary, and liver cancers. This distribution is consistent with prior epidemiological reports [3, 10, 12], confirming melanoma as the most prevalent underlying malignancy. Melanoma was associated with significantly increased odds of developing irBP after ICI treatment (adjusted OR = 3.21; 95% CI, 1.51–6.58) [10], potentially attributable to tumor-specific express of BP180 autoantigen triggering the production of anti-BP180 autoantibodies upon ICI-induced loss of immune tolerance [20]. While this mechanistically explains melanoma’s predisposition, the pathophysiological links between lung/renal cancer and BP remain unestablished, warranting further studies investigation.

Our disproportionality analysis detected significant BP signals across all four pharmacovigilance metrics (RORs, PRRs, BCPNN, and MGPS). PD-1 inhibitors consistently demonstrated the strongest class-level association with BP, exceeding signals from CTLA-4 and PD-L1 inhibitors across all methodologies. This result is concordant with previous pharmacovigilance studies about cirAEs [21]. At the agent level, cemiplimab (PD-1 inhibitor) monotherapy (ROR 37.96, PRR 37.81, EBGM05 25.21, IC025 3.4) and the combination of atezolizumab (PD-L1 inhibitor) with ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor, ROR 24.14, PRR 24.08, EBGM05 24.07, IC025 4.59) constitutes the most significant risks for irBP.

These findings corroborate previous FAERS-based analyses indicating a significant association between ICIs and BP, with PD-1 inhibitors generally showing elevated signal intensities (our ROR = 22.66; Tan et al. ROR = 24.45), supporting PD-1 blockade’s distinct role in BP pathogenesis. Methodologically, our study’s concurrent reporting of PRR, BCPNN, and MGPS allows for robust cross-algorithm validation of the ROR signals, reducing bias from reliance on a single method. Through agent-level stratification, cemiplimab and nivolumab are recognized as high-risk agents—an advancement beyond the class-level analysis by Tan et al.

Our analysis further identified a distinct hierarchy: PD-1 > CTLA-4 > PD-L1 inhibitors (ROR: 22.66 > 8.79 > 6.55). This contrasts with Tan et al.'s reported ranking (PD-1 > PD-L1 > CTLA-4) [12]. These discrepancies highlight the importance of methodological transparency in pharmacovigilance studies. Likewise, at the agent level, the extremely high-risk magnitudes demonstrated by cemiplimab (ROR = 37.96) and nivolumab (ROR = 29.99) demand the highest level of clinical vigilance.

TTO analysis indicated that the median onset time of irBP was 165.2 days (IQR 56–410), with 17.7% (44/249) of cases occurring within the first month and 50.6% (126/249) emerging after 6 months. This profile is generally consistent with the 204-day median (IQR 57–426) reported by Tan et al., [12] with minor differences possibly reflecting variations in observation periods (our inclusion of earlier cases from 2004 onward) and varying proportion of cases with valid TTO records.

To better understand the temporal dynamics of BP risk, we employed WSP modeling. All β values were <1, suggesting a declining hazard pattern—a characteristic of early-onset events. Among different ICI classes, CTLA-4 inhibitors exhibited the most marked early risk concentration (β = 0.48), whereas PD-L1 (β = 0.69) and PD-1 (β = 0.83) inhibitors exhibited a more extended risk period. Our quantitative confirmation of early failure patterns (β < 1) across all ICI classes complements Tan et al.’s clinical recommendation for long-term monitoring while emphasizing an early high-risk window, particularly for CTLA-4 blockade. Clinically, these findings highlight the importance of surveillance strategies stratified by risk magnitude. For instance, the rapid (median 35.7 days) and highly concentrated early-onset risk window for CTLA-4 inhibitors (β = 0.48), necessitates high-frequency dermatologic evaluation within the first month of initiating blockade. In contrast, PD-1 inhibitors not only carry the highest risk magnitude but also exhibit a much broader risk period (β = 0.83, median TTO 190.5 days), with 50.6% of cases emerging after 6 months. This risk magnitude profile compels the need for long-term, continued vigilance for patients on PD-1/PD-L1 therapies, extending well beyond the initial 6 months. Recognizing and leveraging the distinct “risk magnitude” and “temporal magnitude” across ICI classes and individual agents to design stratified surveillance strategies directly improves the timely detection and effective management of irBP, which is critical for optimizing clinical outcomes.

The limitations of this study inherent to pharmacovigilance databases. First, FAERS database has a voluntary nature with non-peer-reviewed AE data, potentially introducing unmeasured confounding. Second, a causal relationship cannot be established between ICIs and the onset of BP because of a disproportionality analysis. Third, absence of prescription denominator data precludes incidence calculation. Given these limitations, prospective studies are required to confirm these findings.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the work, manuscript revision: Y-GZ. Acquisition, analysis of data, manuscript writing: YW. Literature collection and manuscript writing and revision: L-Y-YY. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by grants from Beijing Natural Science Foundation, grant number 7232118, National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding, grant number 2022-PUMCH-B-092, and National Clinical Key Specialty Project of China.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/jpps.2025.15597/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

WangSJDouganSKDouganM. Immune mechanisms of toxicity from checkpoint inhibitors. Trends Cancer (2023) 9(7):543–53. 10.1016/j.trecan.2023.04.002

2.

SunYZhangZJiaKLiuHZhangF. Autoimmune-related adverse events induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Opin Immunol (2025) 94:102556. 10.1016/j.coi.2025.102556

3.

AsdourianMSShahNJacobyTVReynoldsKLChenST. Association of bullous pemphigoid with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol (2022) 158(8):933–41. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1624

4.

WanGChenWKhattabSRosterKNguyenNYanBet alMulti-organ immune-related adverse events from immune checkpoint inhibitors and their downstream implications: a retrospective multicohort study. Lancet Oncol (2024) 25(8):1053–69. 10.1016/s1470-2045(24)00278-x

5.

KogaHTsutsumiMTeyeKShirahamaTIshiiNAzumaKet alEpitope spreading in immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated bullous pemphigoid. JAMA Dermatol (2025) 161(5):557–9. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.6665

6.

AzinMFarokhPMcGarryALeungBWRosterKRashdanHet alType 2 immunity links eczematous and lichenoid eruptions caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol (2025) 93:1456–63. 10.1016/j.jaad.2025.08.008

7.

LiLHuangYXueRLiGLiLLiangLet alT cell-mediated mechanisms of immune-related adverse events induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol (2025) 213:104808. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2025.104808

8.

TangKSeoJTiuBCLeTKPahalyantsVRavalNSet alAssociation of cutaneous immune-related adverse events with increased survival in patients treated with anti-programmed cell death 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 therapy. JAMA Dermatol (2022) 158(2):189–93. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5476

9.

PruessmannJNPruessmannWSadikCD. Research in practice: immune checkpoint inhibitor related autoimmune bullous dermatosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges (2025) 23(4):441–5. 10.1111/ddg.15638

10.

SaidJTLiuMTaliaJSingerSBSemenovYRWeiEXet alRisk factors for the development of bullous pemphigoid in US patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. JAMA Dermatol (2022) 158(5):552–7. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0354

11.

AggarwalP. Disproportionality analysis of bullous pemphigoid adverse events with PD-1 inhibitors in the FDA adverse event reporting system. Expert Opin Drug Saf (2019) 18(7):623–33. 10.1080/14740338.2019.1619693

12.

TanHChenXChenYOuXYangTYanX. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated bullous pemphigoid: a retrospective and real-world study based on the United States food and drug administration adverse event reporting system. J Dermatol (2025) 52(2):309–16. 10.1111/1346-8138.17517

13.

LuLChenLXuYLiuA. Global incidence and prevalence of bullous pemphigoid: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cosmet Dermatol (2022) 21(10):4818–35. 10.1111/jocd.14797

14.

ArnoldMSinghDLaversanneMVignatJVaccarellaSMeheusFet alGlobal burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol (2022) 158(5):495–503. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0160

15.

LeiterAVeluswamyRRWisniveskyJP. Thes global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2023) 20(9):624–39. 10.1038/s41571-023-00798-3

16.

PadalaSABarsoukAThandraKCSaginalaKMohammedAVakitiAet alEpidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. World J Oncol (2020) 11(3):79–87. 10.14740/wjon1279

17.

KimEJungYSLeeJNamDRYouSHLeeJWet alReal-world utilization patterns of immune checkpoint inhibitors based on the national health insurance service data in Korea. Clin Ther (2025) 47:837–43. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2025.07.014

18.

GandarillasSBergerAStephensonRMehreganDDasgebB. Enriched class II HLA inherence in patients with checkpoint inhibitor-associated bullous pemphigoid. Int J Dermatol (2025) 64(2):399–401. 10.1111/ijd.17563

19.

YangLWangYZuoY. Associated factors related to production of autoantibodies and dermo-epidermal separation in bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol Res (2025) 317(1):303. 10.1007/s00403-024-03760-0

20.

RussoFPiraAMariottiFPapaccioFGiampetruzziARBelleiBet alThe possible and intriguing relationship between bullous pemphigoid and melanoma: speculations on significance and clinical relevance. Front Immunology (2024) 15:1416473. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1416473

21.

LeTKBrownIGoldbergRTaylorMTDengJParthasarathyVet alCutaneous toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: an observational, pharmacovigilance study. J Invest Dermatol (2022) 142(11):2896–908.e4. 10.1016/j.jid.2022.04.020

Summary

Keywords

adverse drug events, immune checkpoint inhibitors, bullous pemphigoid, pharmacovigilance, FAERS

Citation

Wang Y, Yang L-Y-Y and Zuo Y-G (2026) Refined pharmacovigilance assessment of immune checkpoint inhibitors-related bullous pemphigoid: a multi-methodological approach utilizing FAERS database. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 28:15597. doi: 10.3389/jpps.2025.15597

Received

17 September 2025

Revised

16 November 2025

Accepted

19 December 2025

Published

07 January 2026

Volume

28 - 2025

Edited by

Reza Mehvar, Chapman University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wang, Yang and Zuo.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ya-Gang Zuo, zuoyagang@263.net

ORCID: Yan Wang, orcid.org/0000-0002-2350-5533; Liu-Yi-Yi Yang, orcid.org/0009-0001-7241-8399; Ya-Gang Zuo, orcid.org/0000-0002-2526-4331

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.