Abstract

This paper presents a case study about perceptions of residents about the value of publicly funded art and culture institutions (museums, city theatre, and symphony orchestra) in the Finnish city of Jyväskylä. In this study, the kinds of value that residents attribute to these local art and culture institutions and what kind of economic value the visitors’ expenditure to these institutions illustrates are explored. The analysis in this study is based on a survey conducted in 2019 that included the visitors and non-visitors to these institutions as participants. The results illustrate several values of art and culture institutions, which also point to multiple policy domains related to art, economy, social, and wellbeing effects. According to previous studies on cultural policy, it is important to be aware of the various value dimensions of future cultural policy. Though there are conflicting aims regarding cultural values, varied value dimensions complement each other in future-oriented policies.

Introduction

This paper analyses the value of publicly funded art and culture institutions (museums, city theatre, and symphony orchestra, hereafter referred to as JI in this article) in the Finnish city of Jyväskylä. The evidence comes from Nordic context, where a variety of values have traditionally been attached to the functioning of art and culture institutions. Across all Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden), art and culture institutions play a significant role in cultural policy, and they have been and still are considered important vehicles for promoting societal welfare. Therefore, a large share of public funding for culture is allocated to them (Kangas and Vestheim, 2010; Sokka et al., 2022).

One of the major reasons behind the official funding of art and culture institutions has been the aim to civilize, which was an essential part of the public cultural policy already in the nineteenth century (Sokka, 2005; Sokka and Kangas, 2006; Helminen, 2007; Ministry of Education and Culture and Finland, 2017). After World War II and especially from the 1960s onwards, institutions were integrated into municipal service production when the welfare aims of the developing welfare state became connected with the evolving administrative branch of cultural policy (both in Finland as in other Nordic countries) (Duelund, 2003; Sallanen, 2009; Sokka et al., 2022). Furthermore, since the 1990s, economic aims have been added to the existing layers of cultural policy.

Currently, art and culture institutions are entwined in a variety of discussions, such as cultivation of art, democracy, economic importance, as well as local and regional development strategies and sustainability (Kangas, 2004). In the context of regions and cities, culture is nowadays said to boost economic development, regenerate neighbourhoods, increase the attractiveness of cities and regions, and make communities livelier and more cohesive (Florida, 2002; Gibson and Stevenson, 2004; Grodach and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2007; Sacco et al., 2009; Anttiroiko, 2014). At least part of this development can be regarded as “defensive instrumentalism” that does not recognize the enabling functions of culture in society and culture as such; instead, it focuses on measuring without elaborating “a positive, confident and coherent notion of cultural value” (Belfiore, 2012, p. 106).

There is surprisingly little knowledge on how residents value art and culture institutions and whether their perceived valuations, for example, meet the existing motives of public cultural policy. Therefore, this study aims to generate such knowledge. We ask, what kinds of value residents attribute to JI and what kind of economic value their visitors’ expenditure illustrates. Based on empirical evidence, a spectrum of values are illustrated here. Because we believe that it is reasonable to consider value of institutions in all the dimensions we can trace from our data we include also values that are realized through cultural consumption. The approach in this study combines economic analysis and qualitative analysis of the perceived values, thus illustrating the interconnected nature of various value dimensions as well as their attachment to different kinds of argumentation and language within cultural policy.

Empirical evidence about the values reveals some of the expectations that the social environment of the JI poses for the functioning of these institutions in the contemporary society. Such a “mapping” of values may prove valuable when considering the role and development needs of art and cultural institutions in the future. To quote Kangas and Vestheim:

“Institutions are dependent on the social environment to survive, they must all the time prove that they are satisfying some societal need, and meeting some aims, expectations and functions that are not met by other institutions. It is only by fulfilling their aims (which may change, but usually that happens only slowly) that institutions can legitimise their existence” (Kangas and Vestheim, 2010, p. 272).

The significance of values and their perception and role in cultural policy argumentation must be situated in a specific context. The context of this study, Nordic welfare state and its cultural policy, can be considered specific in the variety of various values it presents. Yet—because of this plurality of values—we believe that our results could be useful for cultural policy research in other contexts as well.

Next, we begin by explaining the concept of value and its various meanings. Then we describe the materials and methods used in this study. After that we describe the local and national context of this study. The analysis section begins with a rather traditional economic input-output analysis to show the realisation of economic value through the consumption of culture. After that, we proceed to a more qualitatively oriented analysis of other perceived values of the JI. Finally, the findings and their implications and conclusion are presented.

Value

Studying cultural value may be regarded as a means to understand the various aspects of supporting culture as well as to achieve gains through arts and culture across various policy sectors (Carnwath and Brown, 2014). The dimensions and categorisations of cultural values have been debated throughout the history of Western civilisation (Belfiore and Bennett, 2007a; Belfiore and Bennett, 2007b). The question of how value should be understood and approached has been discussed widely in research (Heinich, 2020; Kaufmann and Gonzales, 2020). There has been significant research focus on the topic in recent years. In the United Kingdom, the Arts Council England (Carnwath and Brown, 2014), the Warwick Commission on the Future of Cultural Value (Belfiore et al., 2019), and the Arts and Humanities Research Council have been active in this sphere of research (Crossick and Kaszynska, 2014; Crossick and Kaszynska, 2016). For example, Garnwath and Brown refer to John Holden’s conceptualization of “institutional value,” which concerns “the value that organisations provide above and beyond the value of their products” (Carnwath and Brown, 2014, p. 41–42,86). However, none of the mentioned researchers have specifically focused on the values that visitors and non-visitors attribute to art and cultural institutions.

Researching the value of culture is also a means of examining the relationship between culture and varied dimensions of public policies. In practice, there seems to be an increasing need for cross-sectoral public policies wherein the various dimensions of culture are recognised, supported, enabled, and developed in a collaborative manner (Gray, 2017; Mangset, 2020; Mujica, 2022). One, perhaps simplified, way to classify the various values of culture is to recognise its economic value, social value, and public value (Carnwath and Brown, 2014). Crossick and Kaszynska identify “components of cultural value” that signify the varied outcomes of cultural activity, including the basis of shaping reflective individuals and engaged citizens with the help of culture (Crossick and Kaszynska, 2014). This implies that the arts and culture have cultural, political, and social effects. However, some dimensions of values can be hard to distinguish from impacts that in many cases become ambiguously attached to value generation. Still, it is not the task of this paper to dwell on the area of impact studies as the aim of this study is simply to recognize which kind of value dimensions can be found from the survey data.

As this study is aimed at empirically illustrating the kinds of values that residents attribute to local art and culture institutions, Armbrecht’s research about perceived values is a rare reference point to our approach (Armbrecht, 2014). Based on a survey of visitors to cultural institutions (museums, instead of a larger set of institutions), Armbrecht analysed the value of cultural institutions, recognizing six categories or value typologies for cultural institutions: economic, education and skills, social, identity, image, and health. Armbrecht emphasises that his value-scale is based on individuals’ perceptions and thus “grounded in individuals’ knowledge about the studied institution” (Armbrecht, 2014, p. 269). As such, it is “to be regarded as one complementary way of understanding the values that cultural institutions provide to society” (Armbrecht, 2014, p. 269). From this perspective, the value of an object is not only contextual but also based on several categories of intrinsic and extrinsic resources, observable, for example, in verbal expressions (Heinich, 2020).

Each of the values presented in the following chapters is based on experiences and attitudes of individual survey respondents. In this sense, they could be thought as illustrations of “intrinsic values,” regardless of what kind of value dimensions may be found: the individual relationship with the institution comes close to that given by John Holden, who calls “intrinsic value” as the “set of values that relate to the subjective experience” (Carnwath and Brown, 2014, p. 86). It is not, however, in the interests here to consider either the “intrinsicity” or the “instrumentality” of the values found in the data of this study. That will be left for future research. Despite acknowledging their importance, this study has not focused on the actual valuation processes, either at the individual or at the social level. The aim of this study was only to recognise the kinds of values that could be tracked from the study’s data.

Materials and methods

This study is based on a survey of existing and potential visitors to the JI that was conducted in 2019. The study’s data represents valuation by individual respondents in the context of Jyväskylä, and it is bound in this context. Yet, these results can provide comparison points for other localities in other Western countries, especially in other Nordic countries, which share similarities in the organisation of art and culture institutions (Kangas and Vestheim, 2010).

We conducted the survey1 as part of a city centre development and regeneration project (Heart of Jyväskylä/Jyväskylän sydän), funded by the Business Services Unit of the City of Jyväskylä. It had 834 respondents, of which 92.6% had visited the institutions during the previous 12 months. The majority (87%) of the respondents reported their place of residence to be in Jyväskylä. The median age of respondents was 68 years. Forty-four percent of the respondents reported university and 21% reported applied sciences as their highest level of education. The largest single category of respondents by occupation or status consisted of pensioners, who accounted for 24% of respondents. Thirty-seven percent of the respondents lived in households/family groups with children under 18 years of age. Eighty-one percent of the respondents were women, 17% were men, and 2.3% chose the option “other/I do not want to answer.” This study’s data thus consists of respondents who are known to attend cultural events and visit cultural facilities, i.e., elderly women with a higher degree of education (Van Eijck, 1997; Chan and Goldthorpe, 2005; Stanbridge, 2007; Christin, 2012; Sokka et al., 2014). This would not have been optimal if the aim had been to have a representative study of who participates and why they visit the art and culture institutions. This was however not the intention, and the nature of the data does not as such affect the efforts made to find which kinds of value dimensions the respondents attributed to JI.

The questionnaire consisted of questions dealing with the institutions as a whole as well as individual institutions and visits to those institutions. The respondents were asked to answer questions based on their latest visit to the JI in the previous 12 months. If they had not visited any of the institutions, they were asked to consider the local institutions in general. The survey mainly targeted visitors to art and cultural institutions; however, some respondents who had not used the services of these institutions were also included by disseminating the questionnaire in both paper and digital formats through various communication channels (for example, the city’s official media channels, social media, and on-site institutions, including public libraries).

The questionnaire included the following themes:

• Frequency of visits to the JI during the previous 12 months and respondent’s relationship with arts and culture

• Description of the most recent visit to the cultural institution: expenditure, company, reason/s for the visit

• Impressions about cultural facilities based on the latest visit: characteristics and quality of the cultural institution, perceived impacts of the visit to the cultural institution on the respondent’s personal life, perceived impact of the cultural institution on the city as a whole

• Suggestions for development/improvement

• Views about roles and impacts of local public libraries

• Views about cultural institutions as part of the development and wellbeing of the city and its residents.

Various methods and data were employed for value analysis. As part of the methodology, we applied qualitative analysis, descriptive statistical analysis, and economical input-output-analysis to the data (see Supplementary Appendix S3). As mentioned, the survey data does not reflect a representative sample of the visitors, nor the entire population of the city. We cannot empirically illustrate any other values than those that are represented in the data. It still provides an understanding about the kinds of values that residents may attach to art and culture institutions. Most likely, we could find inequalities in who participates in JI, but it is not the task of this study. We will however discuss the value dimensions we found in our data from the perspective of equal participation and access to culture.

The opinions and experiences of visitors and the consumption patterns of visitors as well as their local and regional economic effects were analysed. Basic frequencies have been reported in Ruokolainen et al. (2019), but this is the first time any of those results have been presented internationally. Most importantly, for this paper, we engaged in descriptive analysis of the visitors’ behaviour, for example, not just how often different types of institutions were visited by them but also why. Varied methods of analysis were applied in varying degrees to discuss different values. For example, economic value has been illustrated mainly using input-output analysis, whereas image and identity values have been chiefly analysed using descriptive and qualitative means based on written answers of the survey that until now have not been presented.

To a certain extent and by using open text response questions, this study has employed survey as a qualitative tool (Braun et al., 2021). The open responses revealed issues that the respondents valued as important and essential while consuming, enjoying, and/or creating art and culture. The first open question that provided data for this purpose was, “How would you describe yourself in relation to culture?” It received 696 answers, out of which 218 respondents expressed various values that attributed to culture in their lives. The second open question “How could we make the cultural facilities of Jyväskylä more attractive?” received 547 responses. It also revealed valuations through the perceived development of and problems related to the institutions. In analysing the responses to these questions, we have used qualitative content analysis to recognise various value dimensions present within or underpinning the responses (Miles and Huberman, 1994; Silverman, 2001).

Context: arts and culture institutions in Jyväskylä

The city of Jyväskylä is located in the Central Finland region. Jyväskylä fares quite well when compared with other Finnish cities. The total population of the city was 143,420 in the year 2020. The population growth has been steady (around 1,000 new inhabitants per year) during recent years (The City of Jyväskylä, 2022). More importantly, Jyväskylä is a centre of higher education as it has both a research university and a university of applied sciences. The city has a student population of approximately 40,000. In the year 2018, Jyväskylä ranked fourth among Finnish cities and towns with regard to overall image; its strengths included providing better possibilities for study and leisure, offering a healthy environment to grow up in, as well as having a pleasant living environment (The City of Jyväskylä, 2019; The City of Jyväskylä, 2021a).

The analysis in this study included five of the most important publicly funded JI:

• Alvar Aalto Museum

• Jyväskylä City Theatre

• Symphony Orchestra (Jyväskylä Sinfonia)

• Jyväskylä Art Museum

• The Craft Museum of Finland

Four of the institutions are directly connected to the city of Jyväskylä’s administrative and financial instruments, while the Alvar Aalto Museum is a local destination belonging to the Alvar Aalto Foundation.

All of the above institutions receive a considerable amount of funding from the city of Jyväskylä. According to official documents and decisions of the city council, these institutions may be linked to a variety of goals. Jyväskylä City Strategy presents the vision of a “growing and internationally recognised city of education and expertise” and aims at making the city “the best place to live, work and study” (The City of Jyväskylä, 2021a). This strategy, as well as other sector-specific strategies and plans, manifests various values related to the culture, art, and cultural institutions of the city (Luonila and Ruokolainen, 2023).

The strategy includes responsibility, trust, creativity, and openness (The City of Jyväskylä, 2021a). The four strategic goals of the city are as follows: 1) happy, healthy, and participatory citizens; 2) fresh, growth-oriented business policy; 3) wise use of resources; and 4) to emerge as the capital of sport and physical activity in Finland. As part of the goal of “happy, healthy and participatory citizens,” several themes are emphasised: providing opportunities for children and young people to enjoy healthy growth and learn successfully; opportunities to influence decision-making; promoting equality; availability and accessibility of services; and building a strong sense of community to reduce loneliness through multifaceted leisure activities, arts, and culture. Through its aim of “a fresh, growth-oriented business policy,” the strategy seeks to develop Jyväskylä into an international city of culture, events, and tourism, with a charming city centre, and also a city that is capable of attracting employers.

The cultural plan of the city also focuses on four strategic themes: allocation of services, cultural facilities, business policy, and culture as a profession (The City of Jyväskylä, 2021c). In the Centre Vision of the City of Jyväskylä, the art and cultural institutions of the city provide open spaces for participation and venues for cultural events, enabling Jyväskylä to develop as an event city (The City of Jyväskylä, 2021b). Art and culture institutions are also mentioned in strategies and documents that concentrate on the social, health, and wellbeing aspects, such as the Wellbeing Plan, the Inclusion Programme and the Equality Plan of the city (Luonila and Ruokolainen, 2023).

Value dimensions of art and culture institutions in Jyväskylä

Economic value

Art and culture institutions contribute to economic value in various ways. For example, according to Throsby, the economic value of an art museum is derived from the asset value of the buildings and contents as well as from the service flows provided by these assets (Throsby, 2001). The JI buildings have their own accounting values. However, artworks, archaeological resources, or buildings of cultural importance (for example, buildings designed by Alvar Aalto) cannot be easily valued reliably. Consequently, this study focused on the flows of services provided by JI.

Throsby distinguished the economic flows of art museum services as follows: 1) excludable private goods, 2) non-excludable public goods, and 3) beneficial externalities (Throsby, 2001). The same classification has been used in the analysis of the economic value of the JI in this study. According to Throsby’s classification, private goods include the consumption experiences of the visitors. These include economic use values, which can be measured by the value of the tickets sold. Moreover, the visitors may be willing to pay more for the visit than they actually pay. This reflects the utility a visitor receives while buying services. The consumer surplus is the highest if there are no entrance fees. If visitors buy merchandise at the art institution shop, it creates added value for the institutions.

Accordingly, the economic value and valuation of culture can be seen in the consumption patterns of individual JI visitors. For example, the average visitor2 buys tickets, other services, and so on related to the visit. An estimate of these patterns was asked in the survey, and therefore, the following calculations are grounded in consumption patterns expressed by individual survey participants (a survey of existing and potential visitors to the JI that was conducted in 2019). In the case of JI, the median value of consumption was 37 euros (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Place of residence of JI visitors | Alvar Aalto Museum | Jyväskylä Sinfonia | Jyväskylä City Theatre | Jyväskylä Art Museum | The Craft Museum of Finland | All institutions (average) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jyväskylä | 13 € | 43 € | 45 € | 15 € | 22 € | 35 € |

| All others | 40 € | — | 65 € | 43 € | 78 € | 62 € |

| Average | 16 € | 45 € | 47 € | 20 € | 30 € | 37 € |

Median spending per visitor.

Moreover, the economic flows of art and culture institutions may generate economic impacts such as employment and income at their respective locations. These externalities are typically important at the regional level, as they create multiplier effects on the regional economy. Accordingly, in this study, analysis of the regional economic flows of visitors’ consumption was based on the input-output tables of Central Finland for 2014. The effects of spending by visitors under the heads of production, employment, households’ net incomes, and taxes are shown in Supplementary Appendix S2 (how to calculate the economic value of Jyväskylä Art institutions is shown in Supplementary Appendix S3).

The total number of visitors to the JI was 194,257 in 2019. Although foreign visitors contribute to the export income of Central Finland, domestic tourism expenditure is also a form of export income for the region. Athanasopoulos et al. suggests that the demand for domestic tourists has received little attention in the previous studies (Athanasopoulos and Hyndman, 2008; Allen et al., 2009; Athanasopoulos et al., 2014). Domestic tourism can contribute more to the tourism-related industry of the region than foreign tourism, since services aimed at attracting foreign tourists have often been built and tested based on domestic demands (Crouch and Ritchie, 1999; Athanasopoulos et al., 2014). Furthermore, domestic tourism may increase residents’ cultural consumption. It is however difficult to predict the extent to which domestic tourism spending will replace foreign spending.

This study showed that financial spending by visitors living outside Central Finland has had an impact on employment, amounting to approximately 22.9 person-years in Central Finland (see Supplementary Appendix S2).3 The production impact of spending by visitors from outside of Central Finland totalled 2,287,205 euros. As a result of increased demand, state taxes increased by EUR 48,536 and municipal taxes by EUR 127,682. The net income from households increased by EUR 723,767 due to consumption related to art institution visits.

In this study, the economic impact of locals spending on visits to JI, for the entire region of Central Finland, across varied sectors, was also calculated. Such spending has a more significant impact on regional production and employment, compared with spending by visitors from outside of Central Finland. The estimated money flows from visitors to JI, who were living in Jyväskylä and elsewhere in Central Finland, totalled EUR 8.46 million. Spending by visitors living in Central Finland, during their visits to the JI, affected employment across different sectors in Central Finland by 122.9 person-years (Supplementary Appendix S2). Based on the regional input-output analysis, the production impact of spending by Central Finland inhabitants during JI visits totalled EUR 12,226 million, including the multiplier effect on various industries. The total impact on state taxes was EUR 260,615, whereas the impact on municipal taxes was EUR 685,560. Households’ net income increased by EUR 2,623 million.4

The JI also provide collective benefits. The economic value of the benefits of these public goods may be evaluated using the contingent valuation method.5 In this study, we did not attribute economic valuation to these benefits. However, a previous research found that the residents of Jyväskylä were willing to pay more than what they actually paid for the existence of the Museum of Central Finland, through their taxes (Tohmo, 2009). Consequently, Jyväskylä taxpayers received value from the existence of the Central Finland museum, which exceeded the public funding used to pay for its existence.

Image and identity

The role of arts and culture in shaping local identities as well as in constructing the images or brands of places has been recognised by research studies and utilised widely in urban public development policies. Influential studies by Landry (2000) and Florida (2002), have highlighted the role of creativity and urban cultural amenities in attracting a skilled workforce and shaping cities into sites of innovation and economic activity, which may be concretised in various ways: cultural capital theme years, cultural events, public space art schemes, cultural flagship projects, such as impressive cultural buildings, and so on (Richards and Wilson, 2004; McCarthy, 2006; Grodach, 2008; Garcia, 2017; Richards, 2017). All this is done to “characterise cities as a unique urban space and create authenticity” (Ulldemolins, 2014, p. 3026).

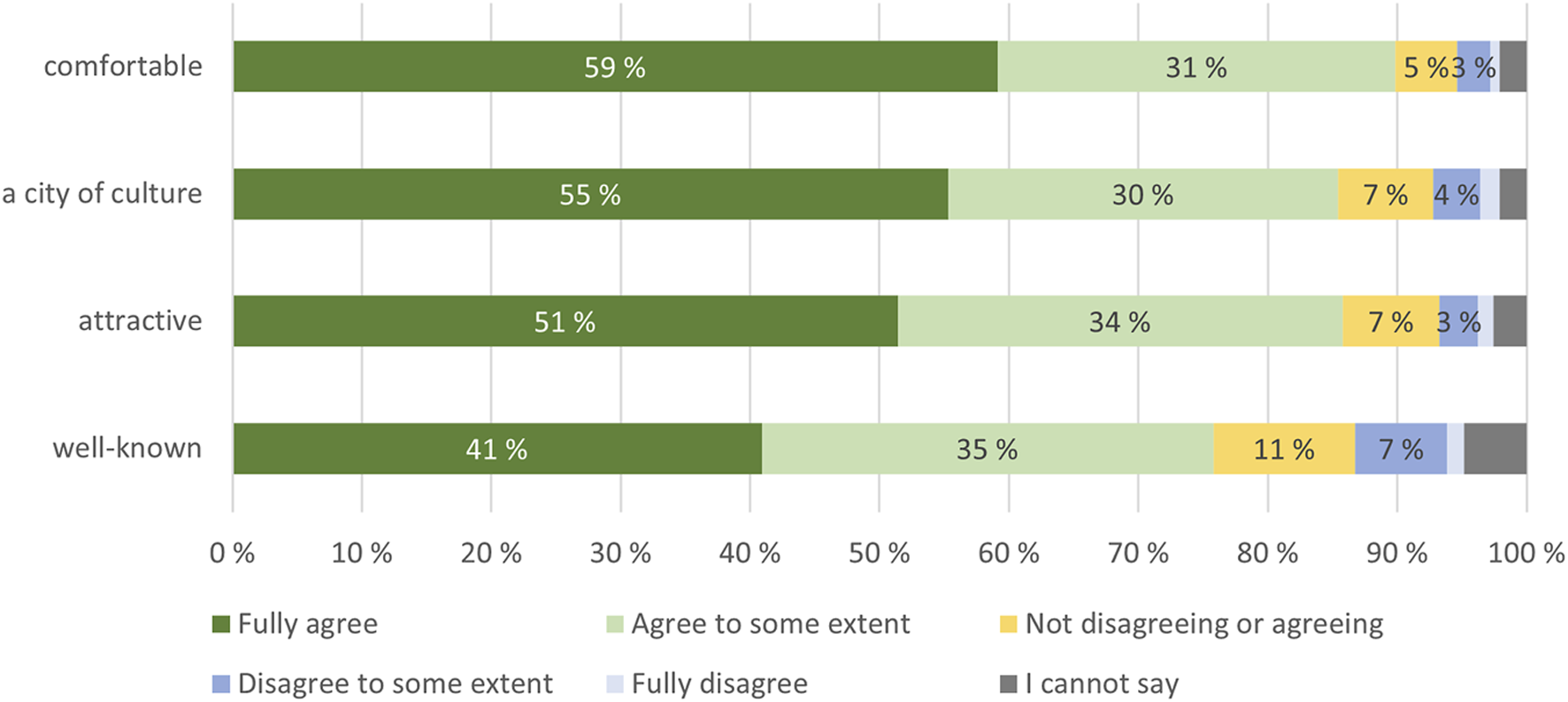

The respondents of our survey valued the impact of the JI on the image and attractiveness of the city in various ways (Figure 1). The majority (92.6%) of the respondents were frequent visitors to these cultural institutions. Ninety percent of the respondents agreed, to at least some extent, that the cultural facility they had last visited during the previous 12 months helped make the city of Jyväskylä comfortable. Eighty-five percent of them thought that the cultural facility they had recently visited helped make the city attractive, whereas 76% thought that the facility helped to make the city well known. Eighty-five percent of the respondents agreed, to at least some extent, that the cultural facilities made Jyväskylä a city of culture.

FIGURE 1

Cultural facility helps to make the city... (comfortable n = 821, a city of culture n = 814, attractive n = 816, well-known n = 813).

The JI thus seems to play a role in constructing the image or brand of the city. Further, they also provide a basis for the identity of individual respondents as well as the local collective identity of Jyväskylä and its people. According to our data, culture manifests itself on a broad spectrum, emerging from the identities and self-perception of individual visitors and ranging all the way to the collective identity of Jyväskylä and its role as a city of culture. Our data highlighted the residents’ own experience of their city and its art and culture institutions. The results presented are, therefore, more about the creation of the city dwellers’ own urban identity through arts and cultural institutions than about the external image of the city. However, from the point of view of the city’s attractiveness, the positive experience of those already living in the city is also important.

The apparently superficial image or brand related to a place is rooted in the deeper identity of the place or the collective identity of people living in a particular place (Fan, 2010). Ulldemolins claims that place branding processes cannot start from scratch or banish the existing culture (Ulldemolins, 2014). Also, he states that branding should be based on local identities, instead of creating artificial narratives. Similarly, Bianchini and Ghilardi recommend that place marketing should be “cultured,” that is, there should be awareness of traditions of cultural expression, and rooted in history and socioeconomic realities as well as the cultural life and representations of a locality (Bianchini and Ghilardi, 2007). In our case, art and culture institutions may be regarded as places where individuals are offered opportunities to engage with the community and to influence how the city is perceived among both the residents and the visitors from outside. All this emphasises localised understandings of art and culture values, including the impact of art and culture on a person’s feelings and the ways in which they interact with place (Mackay et al., 2021).

Although our survey did not explicitly deal with issues such as self-perception, self-expression, or personal identity, many of the respondents (99 written responses to the question “How would you describe yourself in relation to culture?”) described these matters, which are also acknowledged in previous works (Belfiore and Bennett, 2007a; Radbourne et al., 2010; Azevedo, 2017). In these responses, enjoying art and culture is connected to fundamental aspects or verbs such as “being,” “breathing,” “opening up,” “being aware,” and “realizing.” Several respondents opined that art and culture were important parts of their selves.

“Culture is an important part of me.”

“I cannot imagine my life without it. Cultural pursuits are a key part of life. Through them, I guess, one exists…”

Some respondents also write in a manner that can be connected to the projection or image of oneself to the outside world, such as: “I am a cultural person.” In this case, art and culture are ways of constructing an identity and image of oneself. Further, the following responses were recorded for the question, “How could we make the cultural facilities of Jyväskylä more attractive?”:

“Jyväskylä is known as a cultural city. … You should put more effort into it. To take it further. Advertise. Give opportunities to new actors. Maintenance and renovate already well-known and culturally valuable facilities.”

“I hope that at last a proper concert hall will be established here, the kind you can find in many smaller places. Embarrassing that it still lacks one.”

“City Theatre’s renovation is necessary; it is shocking that performances are cancelled when the technology in the house breaks down.”

Such responses bring out the concrete demands for cultural investments and simultaneously emphasise the importance and value of the JI, especially when these institutions seem to be neglected by the local decision-makers. The respondents were concerned about negative developments that could undermine the identity or image of Jyväskylä as a city of culture. There were critical comments about the state of funding and that the lack of investments in culture was “embarrassing” or “shocking” to the city. In addition, the respondents were concerned about the working conditions and facilities of artists and how the neglect of these could hinder the reputation of the city. These statements contest the identity of Jyväskylä as a city of art and culture.

While analysing the identity and image values present in the responses, we ended up considering the objectives underlying the activities and roles of institutions as part of the development of the city (Grodach and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2007). Art and culture institutions can relate to tourism promotion, image construction, and place-marketing measures as well as city centre development and regeneration. On the other hand, the role of institutions in urban development is also reflected in how they help create cosy, vivid, diverse, and participatory urban spaces. Consequently, institutions are not quite facade-like places of cultural consumption and “billboards” of the city’s image but can become part of the urban space, thus empowering urban dwellers with opportunities to express themselves and interact.

Social relations

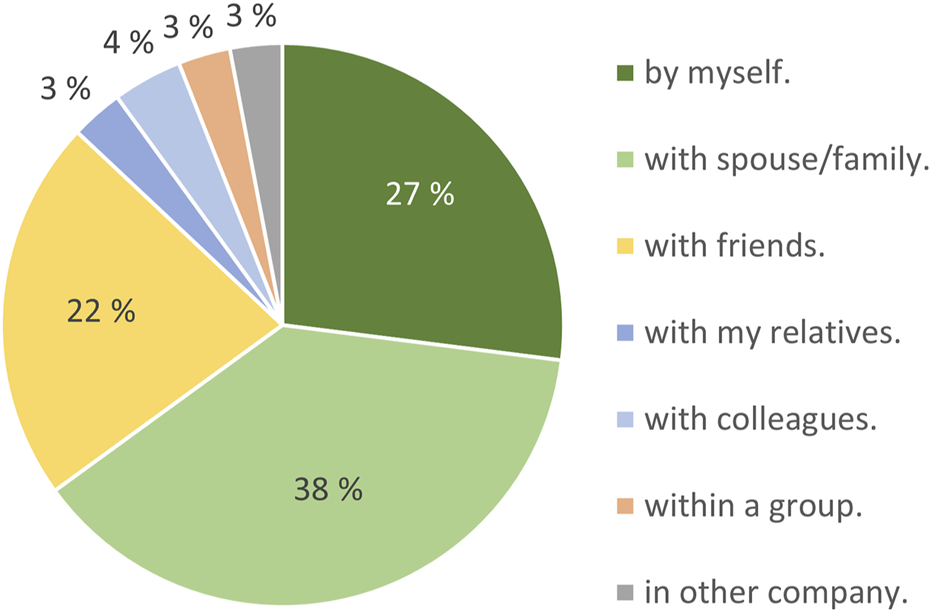

According to our data, 80% of the respondents thought, at least to some extent, that visiting art and culture institutions promotes social relations. It may be summed up that visiting art and culture institutions was thought to be a collective and social activity among the respondents. Only 27% of those who had visited the institutions had come there alone (Figure 2). The most common forms of company cited were spouse or family (38%) and friends (22%).

FIGURE 2

I arrived... (n = 756).

Almost half of the responses to the open question “Why did you come to the cultural facility this particular time?” emphasised the cultural content provided by the institution. Only some respondents explicitly expressed the social aspects of culture in their written answers, summarising how these social aspects are present in the immediate moment of experiencing culture with others, connecting to the broader community through the cultural content, and regarding institutions as communal places.

“Culture, in my opinion, comes to be best experienced along with other people. Shared pleasure is the best pleasure.”

“I think museums and libraries are really important to myself. They are … places that make me strongly feel like I am part of the community.”

Previous research has covered a broad array of impressions that count as “social impacts,” mainly due to the importance of communal human actions in generating them (KEA, 2006; Belfiore and Bennett, 2007a; Belfiore and Bennett, 2007b; Council of Europe, 2017; Lindström Sol et al., 2022; MESOC, 2023). In the context of regions and cities, culture is said, for example, to regenerate neighbourhoods, make communities livelier and increase their cohesion (Matarasso, 1997; Grodach and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2007; Sacco et al., 2009). Such “impacts” are however also stressed to “be complex relationships that sometimes cannot be measured directly” (MESOC, 2023, p. 17).

Armbrecht (2014) sees the social value of culture profoundly entangled with social relations and networks (Bourdieu, 1973; Putnam, 2001; Bourdieu, 2008). According to him, “Cultural institutions are facilitators and catalysts of social interaction and the construction of social networks” (Armbrecht, 2014, p. 255). From previous research, we already know that cultural facilities could (and should) be designed as enabling spaces that facilitate dialogue and participation (MESOC, 2023). Our case also illustrates that established institutions undoubtedly could contribute more than they do currently to their surrounding society if they could provide broader access to their actions and invite more diverse groups of visitors to participate in their actions.

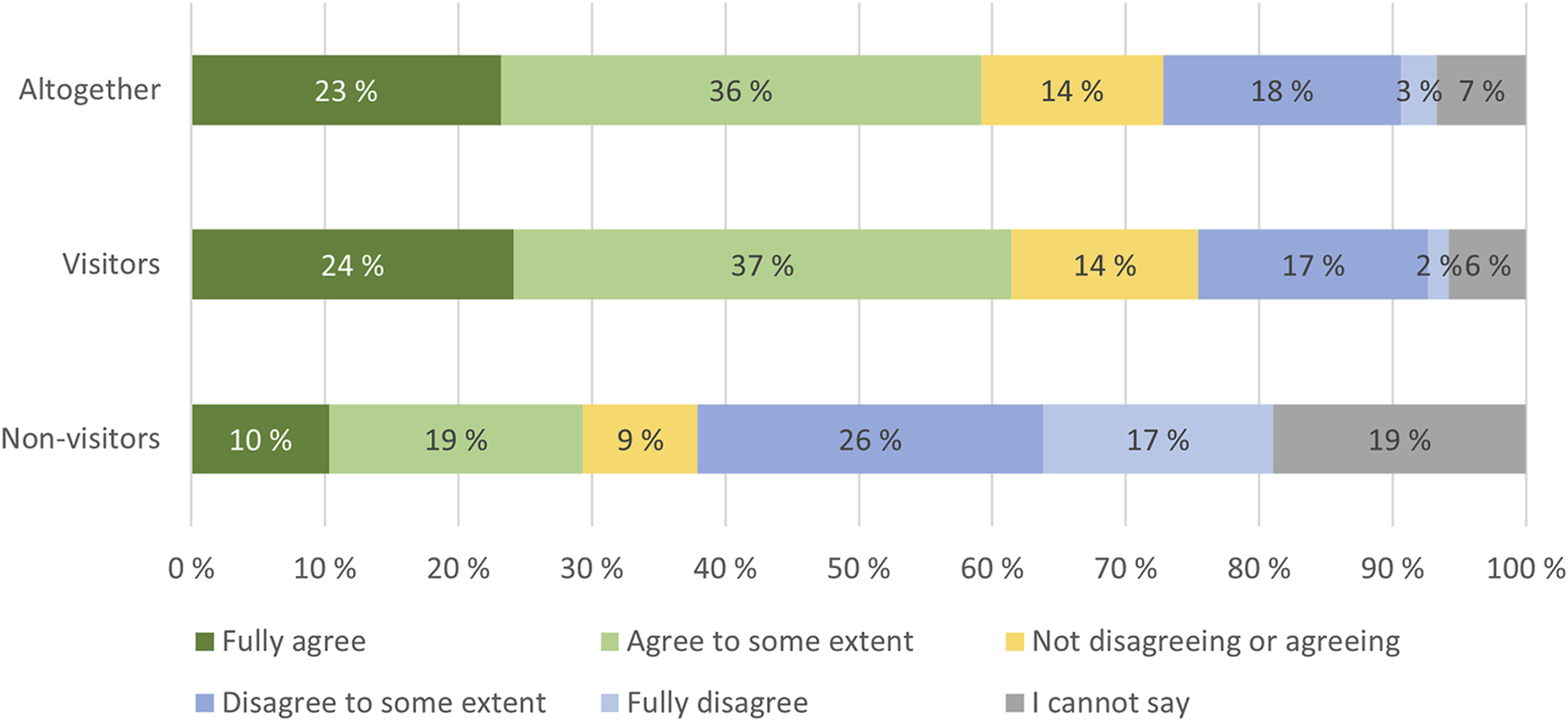

Despite the evidence regarding the importance of social relations for our respondents, the JI were not considered to be especially inclusive in their actions (Figure 3). Most striking result was that only 59% of them thought that the JI affected all the citizens of Jyväskylä. Those who visited the institutions and used their services enjoyed and produced the social value of culture, but a large proportion of Jyväskylä residents seemed to be left out (cf. Stevenson and Balling, 2017). This evidently is an important issue that requires further research.

FIGURE 3

The facility and its activity affect all citizens (n = 820, visitors n = 761, non-visitors n = 58).

Capacities and skills

Cultural institutions are also known to help in transmitting and disseminating skills and knowledge; an example of this is the role of cultural institutions in (arts) education. We did not however come across capabilities and skills in our data through instances such as arts education, school visits, or enabling of cultural participation. Instead, acquisition of occupationally relevant knowledge and maintenance of skills needed for creative activities were mixed with genuine personal interest in arts and creative content offered by institutions.

In our data, 94% of the respondents acknowledged the role of art and culture institutions in human development, when they agreed that visiting a “culture institution civilised” them. Further, for 84% of the respondents, visiting institutions inspired one to cultivate art as a hobby, whereas for 58% of the respondents, such visits inspired the creation of art. The growth of professionals and occupational development in the fields of art and culture can thus be regarded as one of the means of realising capabilities and skills generated by cultural institutions (Mackay et al., 2021). The capabilities and skills approach to cultural value came across as essential, both for occupational terms and as a human way of living, developing, and experiencing.

“(Culture is a) (p)rofession and hobby, a lifeline in many ways.”

“Work, hobby, whole life, among which now the emphasis is work.”

Art and culture institutions are also reported to play a part in other creative processes that generate new knowledge and enhance new skills (Armbrecht, 2014). Recently, for example, the OECD has emphasised the importance of “cultural and creative sectors” as “a source of creative skills” that “also have a role to play in increasing educational performance generally” (OECD, 2021, p. 2). Similar views have been expressed by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD, 2023).

A recent EU-report states how “analyses of population surveys support a clear link between participation in cultural activities and patterns of engagement with key civic and democratic activities as well as democratic and civic values” (Hammonds, 2023, p. 74). OECD experts suggest how creative thinking “can improve a range of other skills and capabilities, from metacognitive capacities to inter- and intra-personal and problem-solving skills” (OECD, 2021, p. 16). This can be linked to capacity building and the positive impacts of having opportunities for self-representation. Such impacts are not easily measurable (Sacco et al., 2013; Mackay et al., 2021; OECD, 2022), which becomes no easier after acknowledging the differences between capacities and capabilities: the former generally refers to knowledge and skills in “development speak,” whereas the latter can be regarded as a central element in human development (Sacco et al., 2013; de Beukelaar and Spence, 2019). Still, based on our survey, the capability approach, in particular, could be further developed also in the context (though not limited to them) of established art and culture institutions—through widening the access and participation in the activities they produce, institutions could have profound meaning for the functioning of democracy (Hammonds, 2023).

Health and wellbeing

In our data, as many as 95% of the respondents agreed, at least to some extent, with the proposition that visiting a cultural facility is good for one’s wellbeing. Obviously, we can talk about health and wellbeing only related to JI here; many modes of culture deserving attention remain unexplored. Our results however show that JI are perceived as important for health and wellbeing even among those who did not visit them.

A total of 77% of those respondents who had not visited any of the institutions in the past 12 months agreed, to at least some extent, that visiting institutions would be good for their wellbeing. Perhaps, they were aware of the discussion around the impact of culture and art on wellbeing, or they may have reflected on their previous visit to an art or cultural institution more than a year ago, which was excluded from the period of our questionnaire.

In any case, in the previous year, both visitors and non-visitors to the JI recognised the importance of the institutions for their own wellbeing. Further, there were 51 health-related open responses to the question, “How would you describe yourself in relation to culture?” The respondents talked about how culture helped them cope with the struggles of everyday life and how culture somehow transcended everyday life to give them strength. The responses ranged from descriptions of “lighter” effects, such as the role that culture played as a relaxing, delightful, empowering, and invigorating activity in everyday life, to more fundamental and perhaps even sinister meanings of culture in the lives of the respondents, such as coping with the help of culture and seeing culture as an absolute necessity to oneself or a way to survive.

“I enjoy culture! It empowers, in many ways …”

“Cultural events invigorate and relax.”

“Culture helps me to cope with everyday life.”

There were also several explicit expressions of the word “wellbeing” in relation to culture and the arts:

“I use culture to maintain my mental wellbeing!”

“Cultural services bring wellbeing and contentment to life, at all stages of life.”

Interest in research around the area of culture, health, and wellbeing has grown over the past decade, although leaving the role of everyday cultural participation under-explored (Dowlen, 2023). Broadly speaking, arts and culture have been found to generate positive effects on the wellbeing of a person (Wheatley and Bickerton, 2019). In 2019, the WHO published a scoping review focusing on the evidence base of the role of arts in improving wellbeing. The scoping identified over 900 publications, of which several were systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses, covering over 3,000 different publications (Fancourt and Finn, 2019). Several health effects were identified, which were related to visits to art and culture facilities. According to the evidence base, visiting museums, theatres, galleries, concerts, and operas resulted in lower rate of cognitive decline, lower risk of dementia in older age, enhancement of self-worth, and development of coping mechanisms.

The Finnish term for “wellbeing” (“hyvinvointi”), which was used in our questionnaire, refers both to physical health and “feeling good,” covering both the physical and mental sides of health. Further, it also refers to “material wellbeing”.6 The Finnish language, therefore, encompasses a wide understanding of wellbeing, wherein an environment viable for actualising one’s social, psychological, and physical resources is crucial for experiencing wellbeing (Dodge et al., 2012).

In practice, perceived physical and mental health are often used interchangeably with wellbeing, and both are used to imply the quality of life (McCrary et al., 2022). The general effects of art attendance on happiness have also been found (Hand, 2018). Parallel to our results, there is evidence that higher attendance results in greater levels of happiness; in fact, even less frequent attendance in some activities has been found to indicate positive association with life satisfaction (Wheatley and Bickerton, 2017).

Wellbeing may even be considered to result from the participation of city dwellers in institutional activities, since the experience of inclusion may be considered a significant part of the experience of wellbeing (Dodge et al., 2012). As mentioned earlier, 40% of respondents disagreed with the proposition that institutions impact all citizens (or did not know how to answer the question regarding the inclusiveness of institutions). This creates a somewhat contradictory picture of the impact of institutions on urban residents’ wellbeing. Viewed through the lens of inclusion of citizens, it appears that institutional activities do not include all residents and not all welfare impacts take place fully. The results however remind us of the possibility of developing the established institutions towards more participatory ways of functioning. In the context of our case, this is feasible, as we recall that access and participation are recognized as important development goals (The City of Jyväskylä, 2021a).

Discussion of the results: from strictly economic to broader values of culture

In Finland, as in all other Nordic countries, art and culture institutions occupy an important, institutionalised place in cultural policy (Duelund, 2003; Kangas and Vestheim, 2010). In Finland, the establishment of these organisations dates back to civil society activities aimed at social development (Sokka, 2005; Sokka and Kangas, 2007). Art and culture institutions in Jyväskylä have historically fulfilled several societal functions, which have been tied to various kinds of values over time. Based on the obvious importance of these institutions, it could be hypothesised that we might find several kinds of values intertwined with our institutions. Still, we do not know much about how residents value these institutions.

An earlier article by Armbrecht gave us a feasible reference point. As anticipated, we detected several perceived values of the JI, closely resembling Armbrecht’s findings in Austrian data (Armbrecht, 2014). For further studies, it is however important to note that different communities with different degrees of immigration and diversity, for example, might provide different kinds of emphases of the value dimensions that were found in Jyväskylä.

Based on our data, the JI generate economic value; they impact regional production and employment, exceeding the amount of public funding they receive. However, the JI also have other significant values. For example, they shape local identities and the image of the city: our respondents opined that the JI make their native city comfortable, attractive, and well known; they also felt that the JI are important in social relations. Visiting institutions is often a collective and social activity, highlighting the importance of art and culture institutions as communal places, which, through social relations, can help generate several kinds of positive impacts. However, such impacts affect only those who visit these institutions and not all citizens, as indicated by several respondents, especially non-visitors.

When discussing the perceived values of art and culture institutions, one of the most obvious questions is: Whose value are we talking of? We are aware that, in Finland, as elsewhere, both higher level of education and gender meaningfully impact visits to museums, theatres, and symphony concerts (Van Eijck, 1997; Chan and Goldthorpe, 2005; Christin, 2012). It must be conceded that elderly women with a degree have been over-represented in our data. However, our study did not focus on the socioeconomic background of the visitors: we aimed simply at identifying the kinds of values of art and culture institutions available in our data and using this knowledge in the discussion about such values.

It is obvious that the valuations of varied groups should be examined in future in relation to several forms of culture, and not just the institutions our case covers. Recently, this has been done in the EU-funded research project, INVENT. Initial results of the project reveal how the Finnish people hold institutions, especially museums, in high regard, overall.7 We have no reason to believe that Jyväskylä residents were somehow different in this respect. The respondents in our data, at least, were not.

Our results have shown that publicly funded art and culture institutions, which form the backbone of Finnish cultural policy, have multiple values attached to various kinds of public policy aims pointing to multiple policy domains: it is not just about art, nor is it just about economy or social and wellbeing effects. In fact, the value dimensions that we found in our data seem important for the legitimacy of public funding allocated to these institutions.

Perception of values links them to individual knowledge and experiences, which apparently vary among individuals as per their social contexts. Art and culture institutions also relate to the principles according to which value is bestowed upon an object (e.g., “the beauty of a thing”) (Heinich, 2020, p. 87–88). This means that our analysis, to use Heinich’s terms, includes “value-as-worth,” as well as “value-as-goods,” and “values-as-principles” (Heinich, 2020, p. 88). Some respondents, for example, perceive value in the virtues they attribute to the JI. Our analysis did not directly answer Heinich’s call for generating more emphatic methodology in researching the actual valuation processes, because it would require a different kind of research setting and data (Heinich, 2020). This question also connects the valuation of culture to processes of shared knowledge and social learning, which lead further to questions about participation in value formation (Kenter et al., 2016; Klamer, 2016). Participation—who participates, where, and how (on whose terms?)—is an obvious question for further discussion that was not however the focus of this study.

As stated by an earlier research on cultural policy (Gray, 2017; Mangset, 2020; Mujica, 2022), it is important to be aware of various cultural dimensions in developing a future cultural policy. Both in economics and culture, the notion of value can be seen as an expression of worth in a static as well as a dynamic way, as both a negotiated and a transactional phenomenon (Throsby, 2001). For ensuring future legitimacy, studies should focus on openness of the institutions and their social relationships. This is even more crucial, as the respondents view JI to be important for health and wellbeing, and even for human development, as a way of living, growing, and experiencing.

Other researchers have also acknowledged how values are fundamentally plural (Kenter et al., 2016). The plurality and contextuality of value appreciation deter adopting normative approaches to realising value (Crossick and Kaszynska, 2014). When values are complex, inter-subjective, relational, and multidimensional, understanding of contexts and different levels of value realisation is also important for understanding the direction of cultural policy. There exist conflicting aims around cultural values; however, various value dimensions also complement each other in case of future policies (Throsby, 2001). This also implies that, ignoring cultural forms other than publicly funded, established cultural institutions can lead to unequal policies overlooking the heterogeneity of cultural values in modern societies.

As Armbrecht stressed, the contribution of this kind of study “lies in a deeper understanding of why cultural institutions are valuable rather than how the value should be measured” (Armbrecht, 2014, p. 268–269). In this sense, we scrutinised the social context wherein contemporary institutions survive: which kind of needs they are thought to satisfy. All of this has evidently much to do with how the institutions can remain legitimate and important in the face of cultural policy and related public funding (Kangas and Vestheim, 2010). Today, this is especially important when we know that established modes of cultural policies, at least in the way they have been organised in the Nordic countries, are facing several challenges (Sokka et al., 2022).

Conclusion

This paper, based on a survey that we conducted in 2019, presented a case study about the value of city museums, city theatre, and public symphony orchestra in the Finnish city of Jyväskylä. We asked what kinds of value residents attribute to JI and what kind of economic value their visitors’ expenditure illustrates. The Nordic context of our case study emphasized the plurality of values: In the Nordic countries, a large share of public cultural funding is directed towards institutions, and a variety of values has been attached to the functioning of cultural institutions at different historical phases of (cultural) policy development.

In previous research studies, it was common to consider the meaning of cultural actions for a certain value (e.g., economy or wellbeing) in a single study. However, further research is needed on the diversity of various, and often intersecting, values people attach to certain cultural organizations in particular contexts. Our results show that visitors—and perhaps somewhat surprisingly even the non-visitors—attribute many positive values to art and culture institutions in Jyväskylä. We found that the residents attribute a multitude of value dimensions to these institutions that they see having not only economic value but also value for image and identity, social relations, building capabilities and skills, and maintaining health and wellbeing.

The survey was aimed at the visitors and non-visitors alike, but it must be specified that most of the responses were gathered from residents who had visited at least some of the institutions during the last 12 months prior to the time of response. Our data does not represent the population of Jyväskylä, but neither did we aim to do participation study nor consider the meaning of social background for consumption of cultural offerings organized by our case institutions. Our intention was simply to find which kinds of value could be found from the data. We believe that the empirical evidence—especially through our qualitative analysis—about the current values attributed to the institutions in Jyväskylä not only helps to consider the value of established, traditional institutions for contemporary and future policies but also illustrates the broadness of possibilities the institutions have for developing their actions.

Despite the positive value attributions throughout the data (including non-visitors), it was striking how a large share of the respondents (including visitors) felt that these institutions were not inclusive enough in their actions. It is easy to think of cultural policy in which these institutions would partake more strongly in fulfilling the city’s strategic aims, including the attractiveness of the city, its economic development, and widening access and broadening the chances for participation. This however most likely would require new kinds of collaboration between the institutions and other cultural actors and some kind of re-organizing of the existing working methods throughout the city organization and the institutions.

The several values of art and culture institutions we found from our data also point to multiple policy domains related to art, economy, social, and wellbeing effects. Although we know that conflicting aims also exist regarding cultural values, the varied value dimensions can complement each other in future-oriented policies. All this shows the potential that is embedded in the established institutional structure, not only for the art and culture institutions themselves but also for considering cross-sectoral policies that are needed to answer the growingly complex questions existing in the society.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because Dataset may contain information that is potentially identifiable. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to olli.ruokolainen@cupore.fi.

Author contributions

SS, OR, and TT have all worked in a project where the data was gathered. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ejcmp.2023.11618/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^The survey was conducted with the online survey tool Surveypal as well as in paper form. The data was collected anonymously in the period from March to May 2019. An introductory text to the survey explained that data would be used for research purposes and anonymized. Research was conducted along the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK guidelines 2019 (https://tenk.fi/sites/default/files/2021-01/Ethical_review_in_human_sciences_2020.pdf): Participation in the research did not deviate from the principle of informed consent, and therefore, an ethical review statement from a human sciences ethics committee was not needed. Enquiries about the questionnaire can be directed to the corresponding author.

2.^Except for the Alvar Aalto Museum, the share of foreign visitors is low (see Supplementary Appendix S1).

3.^Among the respondents in the survey, there were only a few from outside Central Finland. We used the cost structure of visitors to the entire audience as a basis for analysis. This underestimated the amount of consumption by visitors living outside Central Finland.

4.^Besides consumption experiences, private goods benefits include formal educational activities, curatorial and conservation services, and rewards to donors. Educational activities, which include, for example, instruction of school groups, can increase the stock of human capital in the short or long run. Increased human capital can lead to higher productivity, higher salaries, and higher consumption. For example, museums may display works of practising artists to the public, creating a utility value for those artists. Further, donors gain private utility for supporting art institutions.

5.^As part of the contingent valuation method, individuals are asked directly about how much they are willing to pay for the existence of a cultural feature. In this study, we did not utilise the contingent valuation method. However, we asked visitors to the JI about the spending structure connected to their visit. We analysed the spending related to these visits through an input-output analysis.

6.^ https://www.kielitoimistonsanakirja.fi/#/hyvinvointi?searchMode=all

7.^Based on INVENT, public funding for cultural institutions, such as community centres, museums, and libraries, is regarded as important by Finnish citizens. Theatres and orchestras were not included in the survey (https://inventculture.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Infographic-How-important-do-europeans-find-public-funding-of-culture.pdf).

References

1

Allen D. Yap G. Shareef R. (2009). Modelling interstate tourism demand in Australia: a cointegration approach. Math. Comput. Simul.79, 2733–2740. 10.1016/j.matcom.2008.10.006

2

Anttiroiko A. V. (2014). Creative city policy in the context of urban asymmetry. Local Econ.29, 854–867. 10.1177/0269094214557926

3

Armbrecht J. (2014). Developing a scale for measuring the perceived value of cultural institutions. Cult. Trends23, 252–272. 10.1080/09548963.2014.912041

4

Athanasopoulos G. Deng M. Li G. Song H. (2014). Modelling substitution between domestic and outbound tourism in Australia: a system-of-equations approach. Tour. Manag.45, 159–170. 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.03.018

5

Athanasopoulos G. Hyndman R. J. (2008). Modelling and forecasting Australian domestic tourism. Tour. Manag.29, 19–31. 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.04.009

6

Azevedo M. (2017). The role of culture in development: from tangible and monetary measures towards social ones. Z. Für Kult.3, 47–74. 10.14361/zkmm-2017-0203

7

Belfiore E. (2012). “Defensive instrumentalism” and the legacy of New Labour’s cultural policies. Cult. Trends21 (2), 103–111. 10.1080/09548963.2012.674750

8

Belfiore E. Bennett O. (2007a). Determinants of impact: towards a better understanding of encounters with the arts. Cult. Trends16, 225–275. 10.1080/09548960701479417

9

Belfiore E. Bennett O. (2007b). Rethinking the social impacts of the arts. Int. J. Cult. Policy13, 135–151. 10.1080/10286630701342741

10

Belfiore E. Gibson L. (2019). “Reading the present through the past: a critical introduction,” in Histories of cultural participation, values and governance. Editors BelfioreE.GibsonL. (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK), 1–13.

11

Bianchini F. Ghilardi L. (2007). Thinking culturally about place. Place Branding Public Dipl.3, 280–286. 10.1057/palgrave.pb.6000077

12

Bohlin M. Ternhag G. (1990). Festivalpublik och samhälsekonomien studie av falun folk music festival. Institutet för turism & reseforskning. Högskolan Falun/Borlänge.

13

Bourdieu P. (1973). “Cultural reproduction and social reproduction,” in Knowledge education and cultural change. Editor BrownR. (London: Kegan Paul), 71–112.

14

Bourdieu P. (2008). “The forms of capital,” in Readings in economic sociology. Editor BiggartN. W. (Oxford: Blackwell), 280–291.

15

Braun V. Clarke V. Boulton E. Davey L. McEvoy C. (2021). The online survey as a qualitative research tool. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol.24, 641–654. 10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550

16

Cantell T. (1993). Kannattaako kulttuuri? Kulttuurisektori ja kaupunkien kehityshankkeet. Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskuksen tutkimuksia nro 9. Helsinki: Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskus, 105.

17

Cantell T. (1996). Kaupunkifestivaalien yleisöt - Kuopio tanssii ja soi, Tampereen Teatterikesä. Turun musiikkijuhlat, Ruisrock. Tilastotietoa taiteesta nro 14. Helsinki: Taiteen keskustoimikunta.

18

Carnwath J. D. Brown A. S. (2014). Understanding the value and impacts of cultural experiences: a literature review. Manchester: Arts Council England, 156.

19

Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR) (2019). The economic value of arts and culture in the North of England. in A report for arts council England (London: CEBR), 93.

20

Chan T. W. Goldthorpe J. H. (2005). The social stratification of theatre, dance and cinema attendance. Cult. Trends14, 193–212. 10.1080/09548960500436774

21

Christin A. (2012). Gender and highbrow cultural participation in the United States. Poetics40, 423–443. 10.1016/j.poetic.2012.07.003

22

Clark D. Apostolakis A. (2007). The chichester festival theatre economic impact study 2006. Portsmouth: The Centre for Local and Regional Economic analysis at the university of Portsmouth: University of Portsmouth, 36.

23

Council of Europe (2017). Cultural participation and inclusive societies: a thematic report based on the indicator framework on culture and democracy. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 58.

24

Crossick G. Kaszynska P. (2014). Under construction: towards a framework for cultural value. Cult. Trends23, 120–131. 10.1080/09548963.2014.897453

25

Crossick G. Kaszynska P. (2016). “Understanding the value of arts & culture,” in The AHRC cultural value project (Swindon: Arts and Humanities Research Council), 204.

26

Crouch G. I. Ritchie J. B. (1999). Tourism, competitiveness, and societal prosperity. J. Bus. Res.44, 137–152. 10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00196-3

27

Cwi D. Lyall K. (1977). Economic impacts of arts and cultural institutions: a model for assessment and a case study in Baltimore. research division report# 6. Washington, D.C.: National Endowment for the Arts.

28

de Beukelaar C. Spence K.-M. (2019). Global cultural economy. London: Routledge, 200. 10.4324/9781315617800

29

Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) (1998). Creative industries mapping document. London: DCMS.

30

Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) (2001). Creative Industries mapping document. London: DCMS.

31

Devesa M. Herrero L. C. Saiz J. A. Bedate A. (2006). “Economic analysis of a festival demand. The case of the Valladolid international film festival,” in 14th international conference of the ACEI, Vienna, 6-9 July 2006.

32

Dodge R. Daly A. Huyton J. Sanders L. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing2, 222–235. 10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4

33

Dowlen R. (2023). Vision paper: culture, health and wellbeing. January 2023. Leeds: Centre for Cultural Value.

34

Duelund P. (2003). “The nordic cultural model: summary,” in The Nordic cultural model: Nordic cultural policy in transition. Editor DuelundP. (Copenhagen: Nordic Cultural Institute), 600.

35

Fan Y. (2010). Branding the nation: towards a better understanding. Place Branding Public Dipl.6, 97–103. 10.1057/pb.2010.16

36

Fancourt D. Finn S. (2019). “What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review,” in Health evidence network synthesis report 67 (Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office Europe), 146.

37

Florida R. (2002). The rise of the creative class and how it’s transforming work, community and leisure life. New York: Basic Books, 434.

38

Garcia B. (2017). ‘If everyone says so…’ press narratives and image change in major event host cities. Urban Stud.54, 3178–3198. 10.1177/0042098016674890

39

Gibson L. Stevenson D. (2004). Urban spaces and the uses of culture. Int. J. Cult. Policy10, 1–4. 10.1080/1028663042000212292

40

Gratton C. Taylor P. (1986). Economic impact study: hayfield international jazz festival. Leis. Manag.6 (103), 19‒21.

41

Gray C. (2017). Local government and the arts revisited. Local Gov. Stud.43, 315–322. 10.1080/03003930.2016.1269758

42

Grodach C. (2008). Looking beyond image and tourism: the role of flagship cultural projects in local arts development. Plan. Pract. Res.23, 495–516. 10.1080/02697450802522806

43

Grodach C. Loukaitou-Sideris A. (2007). Cultural development strategies and urban revitalization: a survey of U.S. Cities. Int. J. Cult. Policy13, 349–370. 10.1080/10286630701683235

44

Haaga Instituutti -säätiö (2007). Kaustisen kansanmusiikki-festivaalien vaikutukset vuonna 2007. Haaga-Perho sarja. Helsinki: Haaga yhtymä.

45

Hammonds W. (2023). Culture and democracy: the evidence. How citizens’ participation in cultural activities enhances civic engagement, democracy and social cohesion. Lessons from international research. An independent report commissioned by and authored for the European Commission. Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture Directorate D – directorate for Culture, Creativity and Sport Unit D1 — cultural Policy Unit. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 139.

46

Hand C. (2018). Do the arts make you happy? A quantile regression approach. J. Cult. Econ.42, 271–286. 10.1007/s10824-017-9302-4

47

Heinich N. A. (2020). Pragmatic redefinition of value(s): toward a general model of valuation. Theory, Cult. Soc.37, 5. 10.1177/0263276420915993

48

Helminen M. (2007). Säätyläistön huvista kaikkien kaupunkilaisten ulottuville. Esittävän sävel-ja näyttämötaiteen paikallinen kehitys taidelaitosten verkostoksi 1870–1939. Suomen kulttuuripolitiikan historia -projektin julkaisuja 2. Cuporen julkaisuja 13. Helsinki: Kulttuuripoliittisen tutkimuksen edistämissäätiö, 281.

49

Ilmonen K. Kaipainen J. Tohmo T. (1995). Kunta ja musiikkijuhlat. Kunnallisalan kehittämissäätiön tutkimusjulkaisut, nro 6. Helsinki: KAKS.

50

Kangas A. (2004). “New clothes for cultural policy,” in Construction of cultural policy. SoPhi 94. Editors AhponenP.KangasA. (Jyväskylä: Minerva), 21–40.

51

Kangas A. Vestheim G. (2010). Institutionalism, cultural institutions, and cultural policy in the Nordic countries. Nord. Kult. Tidsskr.13, 2. 10.18261/ISSN2000-8325-2010-02-08

52

Karjalainen T. (1991). Kuhmo chamber music festival. The structure of the festival’s economy and the economic impact of festival. Työpapereita nr 3. Helsinki: Taiteen keskustoimikunta, tutkimus- ja julkaisuyksikkö.

53

Kaufmann L. Gonzales P. (2020). Redeeming the value(s) of the social world. Cult. Sociol.14, 3. 10.1177/1749975520922175

54

KEA (2006). “The economy of culture in Europe,” in Study prepared for the European commission (KEA European Affairs), 355.

55

Kenter J. O. Reed M. S. Fazey I. (2016). The deliberative value formation model. Ecosyst. Serv.21, 194–207. 10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.09.015

56

Klamer A. (2016). The value-based approach to cultural economics. J. Cult. Econ.40, 365–373. 10.1007/s10824-016-9283-8

57

Landry C. (2000). The creative city: a toolkit for urban innovators. London: Earthscan, 300.

58

Lindström Sol S. Gustrén C. Nelhans G. Eklund J. Johannisson J. Blomgren R. (2022). Mapping research on the social impact of the arts: what characterises the field?Open Res. Eur.1, 124. 10.12688/openreseurope.14147.2

59

Luonila M. Ruokolainen O. (2023). “Happy, healthy and participatory citizens”: suburban cultural policy in the Finnish city of Jyväskylä. International Journal of Cultural Policy [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2022.2160714.

60

Mackay S. Klabe H. Hancox D. Gattenhof S. (2021). Understanding the value of creative arts: place-based perspective from regional Australia. Cult. Trends26, 3. 10.1080/09548963.2021.1889343

61

Mangset P. (2020). The end of cultural policy?Int. J. Cult. Policy26, 398–411. 10.1080/10286632.2018.1500560

62

Matarasso F. (1997). Use or ornament: the social impact of participation in the arts. COMEDIA, 112.

63

McCarthy J. (2006). Regeneration of cultural quarters: public art for place image or place identity?J. Urban Des.11, 243–262. 10.1080/13574800600644118

64

McCrary J. M. Altenmuller E. Kretschmer C. Scholz D. S. (2022). Association of music interventions with health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open5, e223236. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.3236

65

MESOC (2023). in Measuring the social dimension of culture: handbook. Editors BonetL.CalvanoG. (Barcelona, Spain: Trànsit Projectes), 130.

66

Mikkonen J. Pasanen K. Taskinen H. (2008). Itäsuomalaisten tapahtumien asiakasprofiilit ja aluetaloudellinen vaikuttavuus. ESS vaikuttaa - tapahtumien arviointihankkeen tutkimusraportti. Matkailualan opetus-ja tutkimuslaitoksen julkaisuja n:o 1. Joensuu: Joensuun yliopistopaino.

67

Miles M. B. Huberman A. M. (1994). An expanded sourcebook: qualitative data analysis. 2th ed.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 338.

68

Ministry of Education and Culture, Finland (2017). Strategy for cultural policy 2025. Finland: Ministry of Education and Culture.

69

Mujica M. M. (2022). Building resilient and sustainable creative and cultural sectors: reshaping policies for creativity: addressing culture as a global public good. Paris, France: UNESCO, 328.

70

Myerscough J. (1988). The economic importance of the arts in Britain. London: Policy studies institute, 221.

71

OECD (2021). Economic and social impact of cultural and creative sectors. Note for Italy G20 Presidency Culture Working Group, 24.

72

OECD (2022). The culture fix: creative places, people, and industries. Local economic and employment development (LEED). Paris: OECD Publishing. 10.1787/991bb520-en

73

O’Hagan J. (1989). The economic and social contribution of the Wexford opera festival. Dublin: Trinity College.

74

Pasanen K. Taskinen H. (2008a). Selvitys kihaus folkin asiakasprofiileista ja alueellisesta vaikuttavuudesta. East side story - puhtia itäsuomalaiseen tapahtumamatkailuun hankkeen tutkimusraportti. Savonlinna: matkailualan opetus-ja tutkimuslaitos. Joensuu: Joensuun yliopisto.

75

Pasanen K. Taskinen H. (2008b). Selvitys mikkelin musiikkijuhlien asiakasprofiileista ja alueellisesta vaikuttavuudesta. East side story - puhtia itäsuomalaiseen tapahtumamatkailuun hankkeen tutkimusraportti. Savonlinna: matkailualan opetus-ja tutkimuslaitos. Joensuu: Joensuun yliopisto.

76

Port Authority of New York, New Jersey, & Cultural Assistance Center (1983). The arts as an industry: their economic importance to the New York-New Jersey metropolitan region. New York, New Jersey: Port Authority of NY & NJ.

77

Putnam R. D. (2001). Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. London: Simon & Schuster, 541.

78

Radbourne J. Glow H. Johanson K. (2010). Measuring the intrinsic benefits of arts attendance. Cult. Trends19, 307–324. 10.1080/09548963.2010.515005

79

Richards G. (2017). From place branding to placemaking: the role of events. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag.8, 8–23. 10.1108/IJEFM-09-2016-0063

80

Richards G. Wilson J. (2004). The impact of cultural events on city image: rotterdam, cultural capital of Europe 2001. Urban Stud.41, 1931–1951. 10.1080/0042098042000256323

81

Rivera M. A. Hara T. Kock G. (2008). Economic impact of cultural events. The case of the Zora! Festival. J. Herit. Tour.3, 121. 10.2167/jht039.0

82

Ruokolainen O. Sokka S. Kurlin A. Tohmo T. (2019). “Taide-ja kulttuurilaitokset osana Jyväskylän kehitystä ja hyvinvointia,” in Cuporen verkkojulkaisuja 56 (Helsinki: CUPORE).

83

Sacco P.-L. Blessi G. T. Nuccio M. (2009). Cultural policies and local planning strategies: what is the role of culture in local sustainable development?J. Arts Manag. Law, Soc.39, 45–64. 10.3200/JAML.39.1.45-64

84

Sacco P.-L. Ferilli G. Blessi G. T. Nuccio M. (2013). Culture as an engine of local development processes: system-wide cultural districts I: theory. Growth Change44 (4), 555–570. 10.1111/grow.12020

85

Sallanen M. (2009). Kaupungin kulttuurivelvollisuudesta kulttuuripalveluksi. Kunnallisten teattereiden ja orkestereiden kehittyminen 1940–1980. Suomen kulttuuripolitiikan historia -projektin julkaisuja 3. Cuporen julkaisuja 16. Helsinki: Kulttuuripoliittisen tutkimuksen edistämissäätiö, 357.

86

Silverman D. (2001). Interpreting qualitative data: methods for analysing talk, text and interaction. 2th ed.London: Sage Publications, 448.

87

Sokka S. (2005). Sisältöä kansallisvaltiolle: taide-elämän järjestäytyminen ja asiantuntijavaltaistuva taiteen tukeminen. Suomen kulttuuripolitiikan historia -projektin julkaisuja 1. Cuporen julkaisuja 8. Helsinki: Kulttuuripoliittisen tutkimuksen edistämissäätiö, 140.

88

Sokka S. Johannisson J. (2022). “Introduction: cultural policy as a balancing act,” in Cultural policy in the nordic welfare states: aims and functions of public funding for culture. Nordisk kulturfakta 2022:01. Editor SokkaS. (Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers), 8–19.

89

Sokka S. Kangas A. (2006). From private inititatives towards the state patronage. Nord. Kult. Tidsskr.9 (1), 116–136.

90

Sokka S. Kangas A. (2007). At the roots of Finnish cultural policy: intellectuals, nationalism, and the arts. Int. J. Cult. Policy13, 2. 10.1080/10286630701342865

91

Sokka S. Kangas A. Itkonen H. Matilainen P. Räisänen P. (2014). Hyvinvointia myös kulttuuri-ja liikuntapalveluista. Kunnallisalan kehittämissäätiön tutkimusjulkaisu -sarjan julkaisu no. 77. Sastamala: KAKS, 108.

92

Stanbridge A. (2007). The tradition of all the dead generations: music and cultural policy. Int. J. Cult. Policy13, 255–271. 10.1080/10286630701556431

93

Stanley D. Rogers J. Smeltzer S. Perron L. (2000). Win, place or show: gauging the economic success of the Renoir and Barnes art exhibits. J. Cult. Econ.24, 3. 10.1023/A:1007652201187

94

Stevenson D. Balling G. (2017). Kann-rasmussen N. Cultural participation in Europe: shared problem or shared problematisation?Int. J. Cult. Policy23, 1. 10.1080/10286632.2015.1043290

95

The City of Jyväskylä (2019). Jyväskylä on muuttokohteena kolmanneksi mieluisin ja kokonaismielikuvissa neljäs. Available at: https://www.jyvaskyla.fi/uutinen/2018-03-26_jyvaskyla-muuttokohteena-kolmanneksi-mieluisin-ja-kokonaismielikuvassa-neljas (Accessed July 25, 2019).

96

The City of Jyväskylä (2021a). Jyväskylä city strategy 2017–2021. Available at: https://www.jyvaskyla.fi/en/jyvaskyla-information/jyvaskyla-city-strategy (Accessed August 4, 2021).

97

The City of Jyväskylä (2021b). Jyväskylän keskustavisio 2030. Kehitystyön teemat, vetovoimatekijät ja tavoitteet [Center Vision of Jyväskylä 2030]. Available at: https://www.jyvaskyla.fi/sites/default/files/atoms/files/jyvaskylan-kaupunki-keskustavisio_hyvaksytty.pdf (Accessed September 10, 2021).

98

The City of Jyväskylä (2021c). Kulttuurisuunnitelma [cultural plan]. Available at: https://beta.jyvaskyla.fi/sites/default/files/atoms/files/jyvaskylan_kulttuurisuunnitelma_29112017.pdf (Accessed September 10, 2021).

99

The City of Jyväskylä (2022). Aluekohtaista tietoa jyväskylästä. Available at: https://www.jyvaskyla.fi/jyvaskyla/tilastotietoa/aluekohtaista-tietoa-jyvaskylasta (Accessed April 4, 2022).

100

Throsby C. D. O’Shea M. (1980). The regional economic impact of the Mildura arts centre. School of economic and financial studies. Macquarie Park: MacQuarrie university, 106. Research paper No. 210.

101

Throsby D. (2001). Economics and culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 208.

102

Tohmo T. (2002). Kulttuuri ja aluetalous - vaikutukset ja käyttäjien kokema hyöty. Taloustieteiden tiedekunta, julkaisuja N:o 131. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopisto.

103

Tohmo T. (2009). The economic value of the museum of Central Finland. Nord. Museol., 123. 10.5617/nm.3217

104