Abstract

The cultural sector was hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic, with economic losses estimated at US$750 billion suffered across the global cultural industry. In response to this crisis, digital transformations have a key role to play in ensuring the vitality of the cultural industry. This paper aims to understand the contribution of technological change in the arts and cultural sectors. Using the Culture Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean organization as a case study, our research demonstrates that individual, organizational and technology-readiness dispositions are key predictors of digital transformations in the cultural sector. Based on an action research approach, our study used a range of qualitative and quantitative methods to collect data over a 9-month period in 2022. In total, data from 7 individual and group interviews, 8 observations in 4 cities, 18 informal discussions, and 70 questionnaires were collected (response rate of 30% of the target population). Analyzed using Lewin’s Change Management Model, the results offer promising avenues for action, paving the way for an understanding of digital transformation in the arts and cultural sectors, an area often neglected in management research.

Introduction

The cultural sector was hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. According to UNESCO (2021), nearly 50% of cultural events around the world were canceled or postponed in 2020, causing economic losses estimated at US$750 billion across the global cultural industry. Since the pandemic, numerous studies have examined how this crisis accelerated the digital transformation of the arts and culture sector (Koshelieva et al., 2023; Leguina et al., 2025; Szostak and Sułkowski, 2024). These studies highlight both the opportunities and the tensions linked to digitalisation, ranging from the increased accessibility of arts and culture to concerns about digital skill inequalities.

Artists have seized the opportunity to turn to digital platforms to democratize their work and reach broader audiences (Holst and Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, 2024; Leguina et al., 2025). The development of information and communication technologies, particularly social media platforms such as Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok, has contributed to the vitality of the cultural sector by enabling new forms of creation, dissemination, and virtual interaction (Koshelieva et al., 2023). These advances rely on a variety of communication channels, some freely accessible, others commercial, through which new works can be created, portfolios distributed, online training provided, and virtual events held (e.g., music shows, visits to museum exhibits) (Observatory of Culture and Communications of Quebec, 2017).

In Canada, however, the technological transition has been relatively slow, a stagnation that also affects the cultural sector. Although many digital tools exist, their adaptation to artistic and cultural contexts remains limited (Canada Council for the Arts, 2021). The mission of the non-profit organization Culture Saguenay Lac-Saint-Jean (hereafter referred to as Culture SLSJ), located on the north shore of the Saint Lawrence in Quebec, is to contribute to the development and influence of workers in the arts and cultural sectors. Culture SLSJ estimates that it is behind on its technological transition by approximately 10 years (Culture, 2021). To address this gap, Culture SLSJ launched in 2022 a digital platform (called Network Culture Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean), designed to centralize the region’s cultural offerings and promote local artists1. This digital platform is designed to highlight talent by enabling artists, cultural workers, and institutional representatives to create profiles showcasing their expertise and services (Côté, 2022). This initiative aligns with the definition of digitalisation as the technological mediation of artistic and cultural experiences, transforming the interaction between creators, artworks, and audiences, and reflecting the broader shift from physical modes of access, expression, and participation to digital forms (Szostak and Sułkowski, 2024; Koshelieva et al., 2023).

The digital platform created by Culture SLSJ can be considered a radical change for the sector–a sector that had not previously been developed a digital tool capable of centralizing the region’s cultural forces. Change management is essential to supporting arts and cultural workers in using digital technologies wisely to create and share works with audiences around the world (Francoeur and Passalacqua, 2023; Holst and Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, 2024). Research estimates the failure rates of change projects at between 20% and 80% (Beer, 2021; Burnes and Jackson, 2011). According to several studies, failing to take the human factor into account is one of the main reasons that change initiatives in the workplace fail (Kotter, 2007; Bareil et al., 2020). The success of a digital transformation initiative depends on a range of individual, organizational and technology-readiness dispositions, including support (Oreg, Vakola, and Armenakis, 2011), skills (Vakola, 2014), beliefs (Armenakis et al., 2007), commitment (Fedor et al., 2006), and optimist (Parasuraman and Colby, 2015).

This study aims to test variables that are often studied in management research (e.g., support, beliefs, skills, commitment) but not in the context of specific cultural settings (e.g., library, museum, theater, cinema, dance, literature), thus departing from the traditional focus on workplaces in management research (among white and blue-collar workers). The objective of the study is to use Culture SLSJ as a case study to analyze an instance of technological change in the form of the implementation of a digital platform. In doing so, this paper positions itself within the broader debate on digital transformation in the arts and culture sector, clarifying its specific contribution to understanding how change management variables operate in creative environments. The research question is as follows:

To what extent do individual, organizational, and technology-readiness dispositions influence intention to use a digital platform among artists and cultural workers?

Given the exploratory nature of the study and our focus on the cultural and arts sectors, both of which have been little studied in change management, it was important to immerse ourselves in the cultural industry to fully grasp the nuances of digital transformation in this environment. Qualitative data was first collected to capture these nuances before then building a questionnaire tailored to the circumstances of the cultural sector. The triangulation of data confirmed the relevance of the theoretical model. The results were analyzed using Kurt Lewin’s change management model (1947), a framework often used in management research but, to our knowledge, never deployed in a cultural and artistic environment.

The paper begins with an overview of the literature and research hypotheses. The methodology and results are then presented. Finally, the theoretical and managerial implications are discussed in light of the relevant literature.

Literature review and theoretical framework

The work of the psychologist and behavioral scientist Kurt Lewin has had a significant influence on change management research since he developed a model in the 1940s that emphasizes the active involvement of people in recognition of the central role they have to play in change processes (Burnes, 2020; Schein, 1988; Schermerhorn et al., 2002). According to Lewin (1947), in order for change to take place, a state of imbalance must be created between a current and a desired situation (Hussain et al., 2018).

Technological change results from a transformation applied to an organization’s processes by the introduction of new technologies or processes that replace existing systems (Gagnon and Préfontaine, 2007). In the case of our study, this transformation corresponds to the development of a digital platform called Network Culture Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean. Transformations of this kind require adaptation to new digital realities since they typically lead to behavioral changes and, in some cases, to a change in vision and values that impact interpersonal relationships (Odoardi et al., 2018). The integration of a new technological tool such as a digital platform can cause significant disruptions in the environment in which it is implemented (Gagnon, 2008; Rojas-Méndez et al., 2017). To maximize the chances of success of a change project, it is important to understand the factors that influence the change in order to minimize resistance to it (Bareil et al., 2007).

Resistance to change is the implicit or explicit expression of defensive reactions against the intention to change (Collerette et al., 2021). It can be considered in two ways: as an obstacle to the success of the change or as a form of feedback that the change agent can take advantage of to facilitate the achievement of the change objectives (Ford et al., 2008). Anticipating potential resistance is a significant challenge since expressions of resistance amount to perceptions and are therefore subjective and difficult to predict (Bareil et al., 2020).

Lewin (1947) developed a three-step change management model that encourages a gradual approach to change involving unfreezing (which requires questioning behaviors and habits), changing (in which new behaviors, processes or structures are implemented to effect the desired change), and refreezing (focused on stabilization and integration of new behaviors into current operations) (Burnes, 2020).

While Lewin’s three-stage model has been criticized for its simplicity, Burnes (2020) argues that, despite its age, Lewin’s theory remains both pertinent and empirically grounded. Far from being simplistic, it is based on a deep understanding of behavioral processes developed through years of empirical observation and offers great flexibility in analyzing change in different contexts (Burnes, 2020; Cummings et al., 2016). Recent studies have revisited Lewin’s framework to demonstrate its continued relevance in contemporary change research, particularly for explaining behavioral and attitudinal dynamics (Bakari et al., 2017; Islam, 2023). Using this framework in the present study provides a theoretical lens to identify key variables, such as individual, organizational, and technology-readiness dispositions, that influence commitment to change and, in turn, can reduce resistance to change (Bakari et al., 2017). By following Lewin’s theory as a tool, this allows us to offer recommendations on how cultural and artistic actors move through the stages of unfreezing, change, and refreezing during the digital transformation process.

Individual dispositions refer to employees’ intrinsic propensities, such as their attitudes and beliefs, whereas organizational dispositions reflect extrinsic propensities, external to the individual, that shape how employees engage with change (Gonzalez et al., 2023). Technology readiness, in turn, aims to better understand individuals’ propensity to adopt and use new technologies (Parasuraman and Colby, 2015).

In the case of individual and organizational dispositions, there is empirical evidence of the importance of factors such as the support of those leading the change initiative and the skills of those targeted by the change (i.e., the recipients of change) together with their beliefs toward change. In a review of the literature covering a period of 60 years (1948–2007), Oreg, Vakola, and Armenakis (2011) demonstrated that organizational support, defined as an organizational disposition, is positively related to change. With regard to individual disposition, Vakola (2014) founded that employees with a high self-perception of their skills tend to perceive change as positive and are more willing to engage in the process. Armenakis et al. (2007) showed that beliefs toward organizational change help to understand the factors that strongly influence the acceptance of the recipients of change and, therefore, their propensity to buy into the change. In this study, two beliefs were measured (appropriateness and valence). Appropriateness assumes that the more people believe the proposed solution is well suited to meeting the challenges faced within their environment, the greater their tendency to be open to change (Collerette et al., 2021). Holt et al. (2007), define valence as “the extent to which one feels that he or she will or will not benefit from the implementation of the prospective change” (p. 238). In other words, the more people believe that change can bring them benefits, the more likely it is that the change will add value to them (Armenakis et al., 2007). Employees engage in change when they perceive it as an opportunity to improve their status and employment conditions (Judge et al., 1999). Drawing on the literature, we propose the following hypotheses:

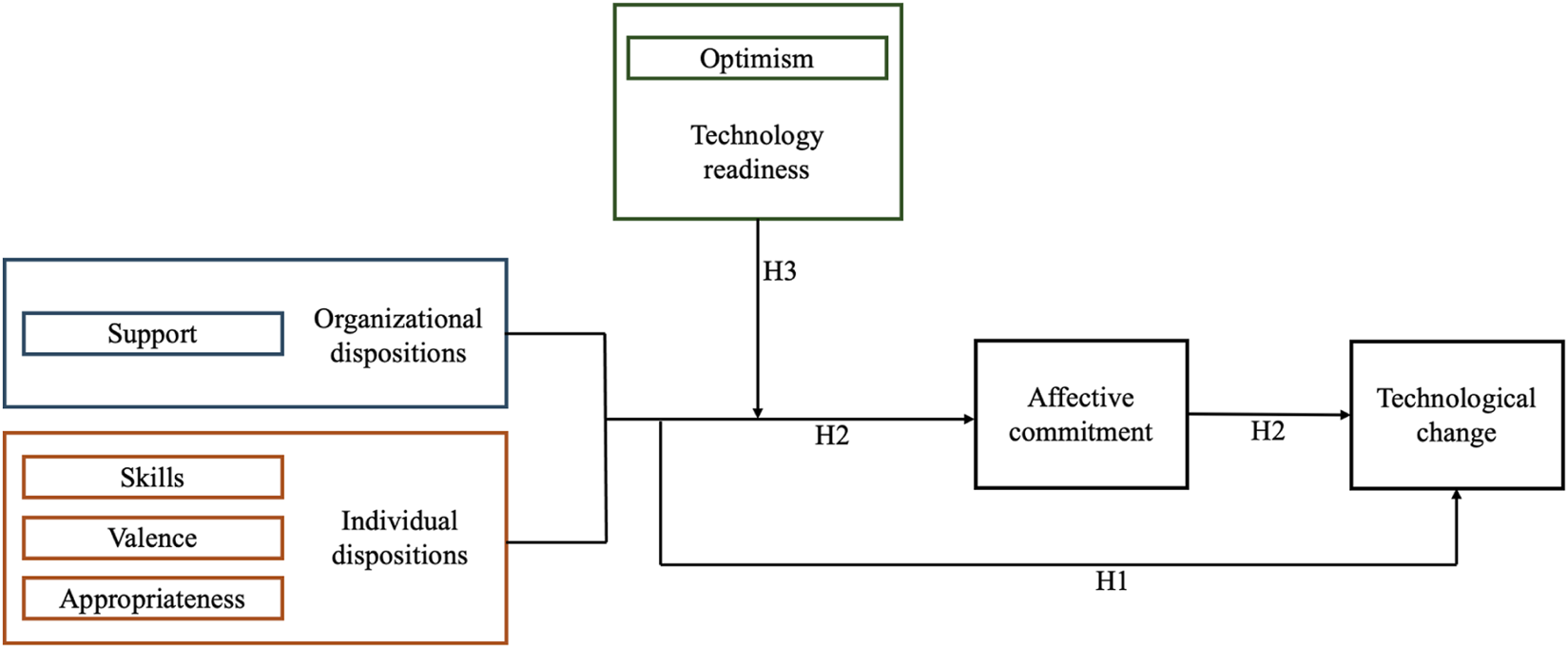

H1

Individual dispositions (skills, valence, appropriateness) and organizational dispositions (support) positively influence change (defined as intention to use the digital platform)

H1a: Skills positively influence intention to use the platform.

H1b: Support positively influences intention to use the platform.

H1c: Valence positively influences intention to use the platform.

H1d: Appropriateness positively influences intention to use the platform.

H2

Affective commitment plays a mediating role between individual and organizational dispositions and change (intention to use the platform)

H2a: Affective commitment plays a mediating role between skills and intention to use the platform.

H2b: Affective commitment plays a mediating role between support and intention to use the platform.

H2c: Affective commitment plays a mediating role between valence and intention to use the platform.

H2d: Affective commitment plays a mediating role between appropriateness and intention to use the platform.

H3

Technology-readiness disposition (optimism) plays a moderating role between organizational and individual dispositions and affective commitment in change (intention to use the platform).

H3a: Technology-readiness disposition plays a moderating role between skill and affective commitment in change.

H3b: Technology-readiness disposition plays a moderating role between support and affective commitment in change.

H3c: Technology-readiness disposition plays a moderating role between valence and affective commitment in change.

H3d: Technology-readiness disposition plays a moderating role between appropriateness and affective commitment in change.

FIGURE 1

Theoretical framework.

Materials and methods

Action research

According to Lewin (1947), action research aims to understand reality, which necessarily involves transforming it (Adelman, 1993). Research of this kind involves a process of co-constructing knowledge with the environment based on a participatory and interactive approach that provides researchers with opportunities to establish a unique dialogue with the field and instill a climate of trust (Adam-Ledunois et al., 2019; Coghlan, 2011; Roy and Prévost, 2022). In contrast to research of a “contemplative” nature, action research has two inseparable objectives (Royer et al., 2009): to support the organization in deliberate action for change and to produce knowledge from observing the transformations made (Krief and Zardet, 2013). For these reasons, action research, as an approach mainly used in change management, is ideally suited to the objectives of this study.

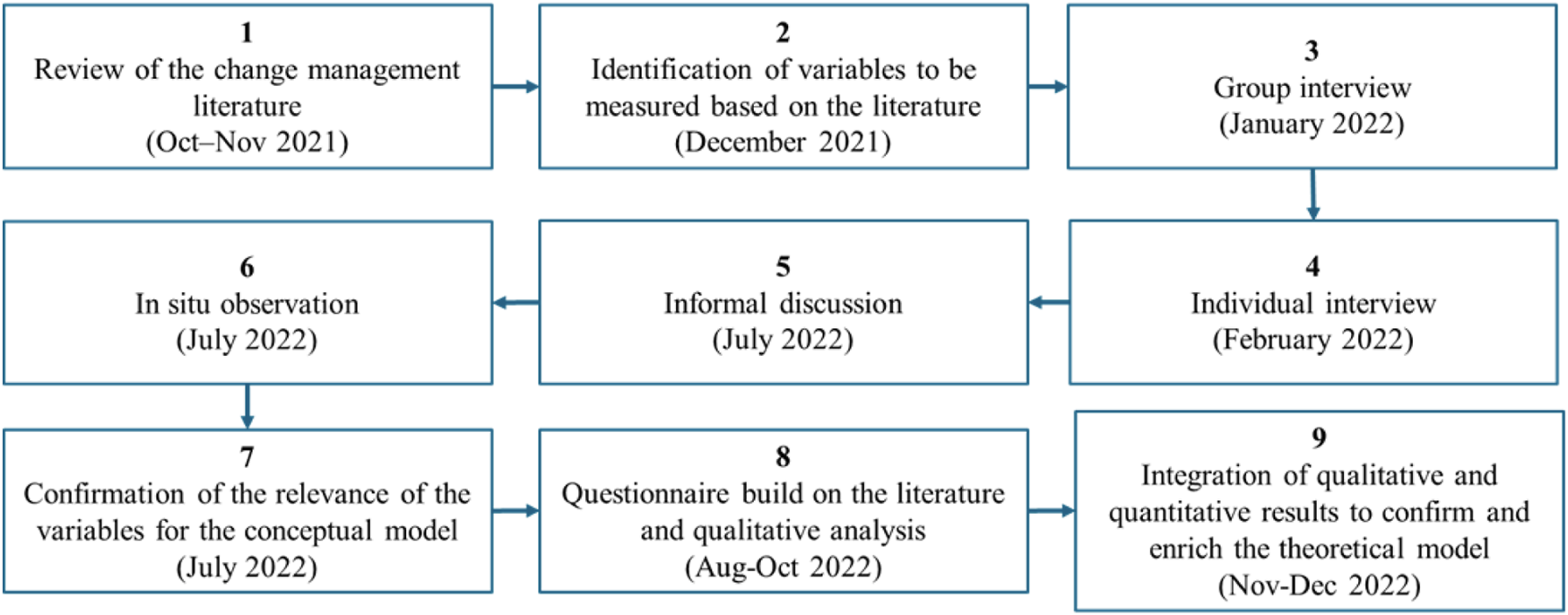

The exploratory nature of the study in the case of art and culture required the use of a range of qualitative and quantitative methods (Shah and Corley, 2006). Employing a range of different methodological approaches is one of the most effective ways of ensuring the success of a change initiative (Oreg et al., 2011). More specifically, we used the change management literature and a conceptual framework designed for traditional organizations that we then exported and adapted to the cultural and artistic environment, which required conducting individual and group interviews before distributing a questionnaire. Primary data collection took place between January 2022 and October 20222. Two methodologies (qualitative and quantitative) were used complementarily, with each serving a different purpose (see Shah and Corley, 2006). The qualitative data helped confirm the choice of variables to be measured to ensure they were grounded in the regional cultural reality. The quantitative data provided a basis for analyzing the cause-and-effect relationships of the theoretical model. Finally, Figure 2 illustrates the sequence of the research process, combining secondary data collection (literature review) with primary data collection (qualitative and quantitative). This mixed-method design reflects a triangulation approach whereby qualitative and quantitative data were mobilized to capture complementary perspectives on the phenomenon (Denzin, 2017; Greene, 2007).

FIGURE 2

Research process.

Qualitative approach: individual and group interviews

A group interview was conducted in January 2022 with three Culture SLSJ employees: the chief executive, the digital development officer, and a project manager. Lasting 75 min, the group interview was considered necessary to ensure a detailed understanding of the case studied (see Yin, 2003) and the issues associated with the implementation of the digital platform and to give participants the opportunity to elaborate on views expressed by others (Ozbilir and Kelloway, 2015). This approach is based on Lewin’s theory of small-group dynamics (Lewin, 1952).

Six individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with potential users of the platform in February 2022 to understand the drivers and barriers. The benefit of this approach is that it enables participants to discuss potential resistance to change without fear of being judged by others (Miles, Huberman and Saldana, 2014). The interviews lasted 60 min. To aid recruitment, Culture SLSJ provided our research team with full access to the field by putting us in direct contact with potential participants. Participation was voluntary.

To construct the interview guides, we relied on methodological principles commonly applied in the social sciences (see Corbière and Nadine, 2020). First, we identified the key concepts of the study based on change management literature review (e.g., skills, beliefs, etc). Second, we validated the relevance and coherence of the themes with the Culture SLSJ senior management team. Third, we defined clear and neutral questions to avoid influencing respondents and ensure each question focused on one idea only. We also arranged the questions in a logical order to facilitate understanding and ensure a natural conversational flow. The development of the questions followed an iterative approach. The guide included 4 sections totaling 17 questions such as: “What might be an impediment to the use of a digital platform?”. The guide was structured as follows: (1) explanation of the process along with a reminder of key information such as the research objectives and consent guidelines; (2) opening questions to initiate the discussion; (3) discussion; (4) conclusion.

The individual and group interviews were conducted via videoconferencing on Zoom. The discussion was led by a facilitator and an assistant responsible for notetaking and recording the interviews. Each interview was transcribed, coded, and analyzed by selecting the key themes linked to the research question (Miles et al., 2014). The profile of respondents is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Number of Participants | Status | Field |

|---|---|---|

| Group interview | ||

| 3 | -Chief Executive (P1) -Digital Development Officer (P2) -Project Manager (P3) | Cultural |

| Individual interview | ||

| 4 | -Director (P4) | Municipal services |

| 5 | -Artist (P5) | Theatre |

| 6 | -Director (P6) | Literature |

| 7 | -Director and artist (P7) | Literature |

| 8 | -Director (P8) | Cinema |

| 9 | -Director and artist (P9) | Theatre |

Profile of participants: individual and group interviews.

Qualitative approach: informal discussions and in situ observation

In addition to the interviews, informal discussions and in situ observation took place over a 5-day period totaling 25 h in July 2022. The sessions were held in participants’ workplaces (e.g., museums, art center). The research team traveled to the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean area (located 470 km from Montreal), visiting eight cultural sites in four cities (Chicoutimi, Alma, La Baie and Val-Jalbert). The richness of these qualitative methods enables immersion in the environment, a key requirement of the action research process (Bradbury et al., 2008; Roy and Prévost, 2022). The aim was to meet other potential users to understand the dispositions that might lead them to use (or not use) a digital platform such as the one considered in this study.

Real-time interactions meant that participants expressed themselves differently than in semi-structured interviews (Lescarbeau, 2010). In the case of the discussions and observations, field notes were taken immediately after the visits (generally in the form of brief descriptions of the locations, snatches of conversation, impressions, etc.) and recorded in a notebook before subsequently being developed (Yousfi, 2019).

During the week of observation and informal discussions, we noted that potential users spoke more freely than in the semi-structured interviews about their motivations and their fears about using the platform (e.g., data security concerns) as suggested by Journé (2018). This enabled us to improve the questionnaire by adding a question on the type of intended use. To address concerns over data security, “ABCD Data” type training and educational sheets on the use of technologies were provided in the spring and summer of 2022. The profile of respondents is shown in Table 2. The research team met with 18 people in total.

TABLE 2

| Sites visited (n = 8) | Status of individuals met (n = 18) |

|---|---|

| Cultural center | -Chief executive officer (P10) -Project manager (P11) -Digital development officer (P12) -Three administrators (P13-P14-P15) |

| Arts center | -A cultural mediator (P16) -An administrator (P17) |

| Publishing house | -A literary publisher (P18) |

| Contemporary art production center | -A production director (P19) -Four artists (P20-P21-P22-P23) |

| 2 artist workshops | -An artist (P24) |

| Museum 1 | -An exhibition officer (P25) |

| Museum 2 | -A director (P26) -A cultural mediator (P27) |

Sites visited and status of individuals met.

Qualitative analysis

The individual and group interviews initially required listening to 435 h of recording to ensure formal transcription. Second, informal discussions and observations were used to complete the analysis of the interviews and validate the hypotheses formulated based on the literature review (Shah and Corley, 2006). Verbatim statements were analyzed using the qualitative analysis software NVivo, enabling accounts to be coded and categorized using an inductive approach (Paillé, 1994).

The thematic analysis followed an iterative process inspired by Braun and Clarke (2006). It began with an initial coding phase in which meaningful segments were identified across the transcripts and descriptive codes systematically assigned in NVivo. This step was followed by thematic grouping, which involved organizing the initial codes into broader themes exploring the barriers and enablers to adopting the new digital platform, as well as suggestions for implementing change.

Based on the change management literature and Kurt Lewin’s three-step theory, several key variables had been identified as determinants in organizational change processes (p. ex. support, skills, beliefs, commitment, technology readiness). The qualitative analysis was therefore not intended to generate new variables but rather to confirm, refine, or prioritize existing ones according to their frequency of occurrence and empirical resonance in the qualitative data collected. The most recurrent and significant themes were then retained for the construction of the conceptual model. These themes were either mentioned explicitly by the interviewees or identified through keywords. For example, four participants referred to the importance of support: “There are many artists who are self-taught, they don’t have the same skills, we need to support them”, or “…you shouldn’t leave anyone behind without support”. Another participant noted that “…there needs to be support and help for the people who need it”, while another’s view was that “we have to help each other along, you can’t just tell people to sort things out themselves”. When several participants underlined the importance of a theme (as was the case with support), the concept was ranked as important, thus confirming the relevance of the theoretical model chosen based on the change management literature.

Analysis of the qualitative data then helped to confirm the relationships between the variables of the theoretical model. For example, a cinema director spoke of commitment as a predictor of platform use: “You have to engage people in the process from the start, it’s then easier to get buy-in.” Confirmation of the importance of relationships was performed through an in-depth and iterative analysis of the data until saturation was reached (Paillé, 1994). Theme saturation was analyzed continuously following the example of Guest, Namey and Chen (2020) based on a new information threshold of 5%. The rigor of the analysis was ensured through the verification of verbatim transcriptions and a systematic coding process (Saldaña, 2021). The triangulation of data, combining qualitative and quantitative insights and quantifying occurrences, confirmed the theoretical model. The qualitative findings also served to contextualize the quantitative results and thereby enrich our understanding of technological change in the cultural and artistic sectors.

Quantitative approach: questionnaire

Sample and data collection

The final approach used was the questionnaire method. Developed from validated scales in the literature and confirmed by the qualitative data analysis, the questionnaire included 29 questions with an estimated completion time of 15 min. Participants were recruited via Culture SLSJ newsletter and social networks, using a convenience sampling method. Before being distributed, the questionnaire was tested among 15 people in the cultural sector to ensure understanding of the questions. The questionnaire was administered on the LimeSurvey platform in September 2022, remaining open until October 2022 (two reminders were sent via email). The cover letter accompanying the questionnaire informed participants about the confidentiality of the results. Since a questionnaire is always voluntary, respondents had the option of withdrawing at any time. To increase the response rate, financial compensation in the form of a gift card was offered. All respondents who completed the survey were eligible for the draw. In total, 10 prizes of $200 were drawn for a total of $2,000. The winners could choose from a range of different products and services in the cultural sector (e.g., books, shows, museum tickets, etc.). The gift card draw was managed on a separate database, and the draw information could not be matched to the questionnaire responses.

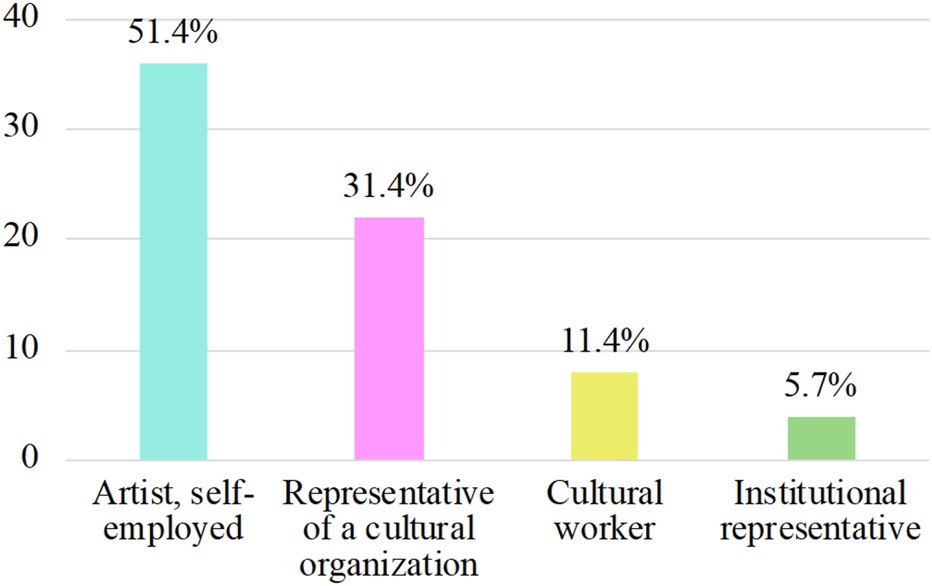

A total of 70 people responded to the questionnaire (giving a response rate of 30% of the target population, i.e., members of Culture SLSJ). The sample size meets the criterion defined by Hair et al. (2010), which states that a social science study should include a minimum of five respondents per measured variable, with the ideal being ten respondents per variable. In our study, 70 participants completed the questionnaire, which included seven variables (support, skills, valence, appropriateness, affective commitment, and optimism), thus meeting the ideal recommended threshold. Moreover, the sample does not differ from the target population in terms of respondent status (artists, self-employed workers and cultural workers, representatives of cultural organizations, and institutional representatives), with a margin of error of 10%3.

The key characteristics of the group of respondents were as follows:

- The majority were aged between 25 and 45 years (65%).

- Most respondents were women (71%).

- Most were university graduates (81%).

- The majority earned between $20,000 and $60,000 (53%).

- The majority worked more than 30 h per week (53%).

Figure 3 shows the distribution of respondents. Artists and self-employed workers account for the bulk of the respondents (51.4%), followed by representatives of cultural organizations (31.5%), cultural workers (11.4%) and institutional representatives (5.7%).

FIGURE 3

Status of respondents.

Measurement scale

We measured individual dispositions: skills, beliefs (valence and appropriateness), organizational disposition (support), technology-readiness (optimism), affective commitment, and technological change (intention to use the platform). Drawn from the literature and the qualitative data, the questions were adapted to the cultural sector. A five-point Likert-type interval scale was used (1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree). Each variable had an alpha between 0.617 and 0.904. Since the questionnaire was exploratory in the case of art and culture, an alpha greater than 0.6 is considered acceptable (Hair et al., 2010). The questions and their reliability can be found in the Supplementary Appendix.

Variables

Dependent variable

Inspired by Masrom’s (2007) scale, developed in a technological context, intention to use the platform was measured using 4 questions on future use (e.g., planned frequency of use) as well as a question on the type of intended use (e.g., networking, promoting one’s work).

Independent variables

Individual dispositions were measured by three variables (skills, valence, appropriateness) while organizational dispositions were measured by one variable (support). These were identified using principal component analysis (PCA) of the measurement scales contained in the questionnaire. The PCA performed on belief (Armenakis et al., 2007) revealed two dimensions: appropriateness (alpha = 0.904) and valence (alpha = 0.899). In addition, PCA of the scale from Collerette et al. (2021) identified support (alpha = 0.692) and skill (alpha = 0.617).

Appropriateness included 5 questions such as “I believe the proposed platform will have a positive effect on how the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean cultural sector operates.” Valence included 4 questions such as “By integrating the platform in my job, I will feel more self-fulfilled.”

The scale developed by Collerette et al. (2021) lists individual and organizational dispositions that can lead to resistance to change if they are not considered. It initially included 15 questions but did not provide interpretable results given the heterogeneity of the questions and the low number of respondents making up the sample. Therefore, a new classification was performed based on the existing change management literature. Two dimensions were retained: support, which included 3 questions such as “In my opinion, leaders in the field visibly support the platform,” and skill, with 3 questions such as “I have the skills or expertise needed to use the platform.”

Mediating variable

The scale developed by Meyer (2016) was used to measure organizational commitment. A PCA was performed on the fifteen questions to reveal three components but only4 the affective commitment was used. The affective commitment component included six questions, such as “I believe that integrating the platform is valid.” and obtained an alpha of 0.857.

Moderating variable

The questionnaire included fifteen questions on technological-related dispositions, and PCA performed on these questions revealed four dimensions: optimism (alpha = 0.852), innovation (alpha = 0.816), insecurity (alpha = 0.798), and discomfort (alpha = 0.715). Given the size of the sample, only one dimension was prioritized (optimism). As defined by Parasuraman and Colby (2015), optimism implies a positive view of technologies. Optimistic people perceive technologies positively and consider that they help to increase their control over their lives, their efficiency, and their flexibility. The optimism variable was measured using four questions, such as “New technologies contribute to a better quality of life”.

Finally, Table 3 summarizes the methodologies used by outlining the approaches, sample, duration, format, and period.

TABLE 3

Methodology  | Approach  | Sample | Duration  | Format  | Period  | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Future users | CSLSJ employees | |||||

| Qualitative | Group interview | -- | 3 | 75 min | Videoconference | January 2022 |

| Individual interview | 6 | 60 min | Videoconference | February 2022 | ||

| Informal discussion | 12 | 6 | 15–60 min | In person | July 2022 | |

| In situobservation | 4 cities: Chicoutimi, Alma, La Baie et Val-Jalbert Locations: Cultural center, arts center, artist workshops, production center, museum, publishing house | 25 h | In person | July 2022 | ||

| Quantitative | Questionnaire | 70 | -- | 15 min | LimeSurvey | September to October 2022 |

Methods and approaches: primary data collection.

Results

Quantitative results

The research model shown in Figure 1 proposes to test a moderated mediation that involves the effect of a moderating variable on the relationship between an independent variable, a mediating variable, and a dependent variable (Hayes, 2017). In concrete terms, our research model hypotheses the interaction of support, skill, valence, and appropriateness (independent variables), affective commitment (mediating variable), optimism (moderating variable), and intention to use the platform (dependent variable).

The MACRO process corresponding to Model 7 was used5. In general, MACRO processes, as developed by Hayes (2017), are based on the principle of random resampling with a replacement (bootstrap method) that involves recreating, from data, a large number of samples (n = 5,000 in this study) of sizes equivalent to that of the initial sample. As a reminder, Hayes (2017) notes that the calculated effect only corresponds to one estimation point. Whether it is positive or negative, in order to be considered significant, the estimation point must have a value other than zero. Therefore, it must fall within a confidence interval that excludes the value zero, i.e., whose lower and upper values are both positive or both negative.

Descriptive statistics

Alongside the correlation between each variable, Table 4 shows the basic information for mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) and the Pearson correlation matrix between variables.

TABLE 4

| Variable number | Variable name | Mean | Standard deviation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Optimism | 3.721 | 0.775 | 1 | ||||||

| 2 | Support | 4.181 | 0.578 | 0.31** | 1 | |||||

| 3 | Skill | 3.457 | 0.776 | 0.24* | 0.48*** | 1 | ||||

| 4 | Appropriateness | 4.111 | 0.631 | 0.3** | 0.65*** | 0.46*** | 1 | |||

| 5 | Valence | 3.136 | 0.846 | 0.31** | 0.39*** | 0.27** | 0.58*** | 1 | ||

| 6 | Affective commitment | 4.367 | 0.501 | 0.46*** | 0.55*** | 0.39*** | 0.65*** | 0.54*** | 1 | |

| 7 | Intention to use | 3.943 | 0.674 | 0.31** | 0.57*** | 0.26** | 0.57*** | 0.52*** | 0,65*** | 1 |

Correlation between the variables.

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01; ****p < 0.001.

Hypothesis testing

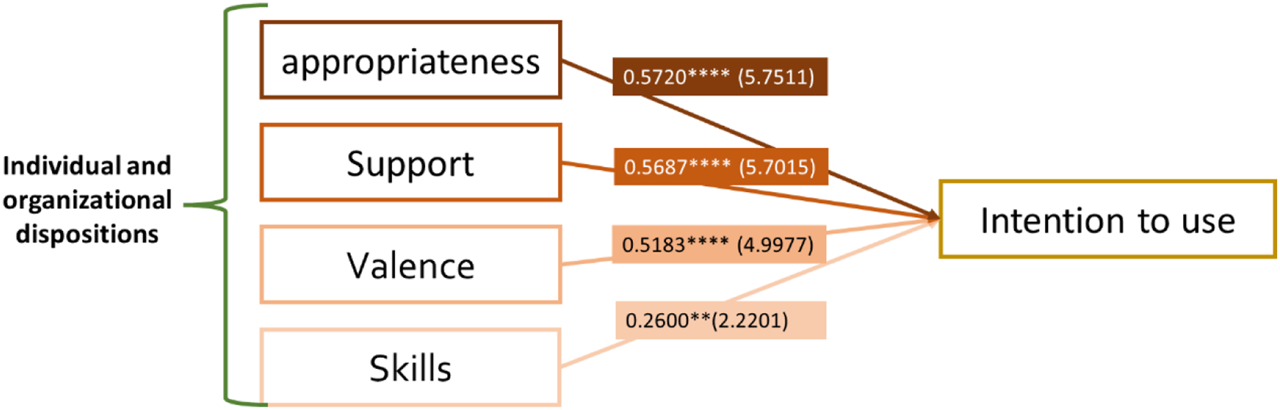

The data reported in Table 5 validates Hypothesis 1: organizational and individual dispositions positively influence intention to use the platform. The data indicates that skills (β = 0.26; p < 0.05; R2 = 0.0676), support (β = 0.5687; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.3234), valence (β = 0.5183; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.7421), and appropriateness (β = 0.5720; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.3272) are significantly and positively correlated to intention to use the platform. Hypotheses H1a, H1b, H1c and H1d are thus confirmed.

TABLE 5

| Hypothesis | Variable | β | ER | t-value | R2 | P-value | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Skills | 0.2600 | 0.1171 | 2.2201 | 0.0676 | 0.0297 | ** | Confirmed |

| H1b | Support | 0.5687 | 0.0997 | 5.7015 | 0.3234 | 0.0000 | **** | Confirmed |

| H1c | Valence | 0.5183 | 0.1037 | 4.9977 | 0.2686 | 0.0000 | **** | Confirmed |

| H1d | Appropriateness | 0.5720 | 0.0995 | 5.7511 | 0.3272 | 0.0000 | **** | Confirmed |

Testing of hypothesis 1.

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01; ****p < 0.001.

The variables can also be ranked based on their capacity to explain intention to use the platform. The higher the t-value, the greater the explanatory power of the independent variable on the dependent variable (Hair et al., 2010). In order, they are appropriateness (5.75), support (5.70), valence (4.99), and skills (2.22) on intention to use the platform (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 4

Ranking of the explanatory power of the independent variables.

The data reported in Table 6 confirms Hypothesis 2: affective commitment plays a mediating role between organizational and individual dispositions and intention to use the platform. The condition stating that the independent variables must be correlated with the mediator is met for the four organizational and individual dispositions: skills (β = 0.2856; p < 0.01; R2 = 0.2989); appropriateness (β = 0.5458; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.4999); valence (β = 0.4537; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.4069); and support (β = 0.4366; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.3954).

TABLE 6

| Hypothesis | Variable | β | ES | t | R2 | P-value | Resulted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2a | Skills | 0.0097 | 0.101 | 0.0960 | 0.4843 | 0.9239 | Confirmed | |

| Affective commitment | 0.6437 | 0.101 | 6.3732 | 0.4843 | 0.0000 | **** | ||

| H2b | Support | 0.3052 | 0.105 | 2.9066 | 0.4193 | 0.0049 | *** | Confirmed |

| Affective commitment | 0.4799 | 0.105 | 4.5704 | 0.4193 | 0.0000 | **** | ||

| H2c | Valence | 0.2392 | 0.1065 | 2.2460 | 0.4598 | 0.0281 | ** | Confirmed |

| Affective commitment | 0.5188 | 0.1065 | 4.8713 | 0.4598 | 0.0000 | **** | ||

| H2d | Appropriateness | 0.2641 | 0.1176 | 2.2457 | 0.4599 | 0.0280 | ** | Confirmed |

| Affective commitment | 0.4769 | 0.1176 | 4.0552 | 0.4599 | 0.0001 | *** | ||

Testing of hypothesis 2.

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01; ****p < 0.001.

However, the model indicates partial mediation of affective commitment between three of the four organizational and individual dispositions (support, valence, and appropriateness) and intention to use the platform. Appropriateness (β = 0.2641; p < 0,05; R2 = 0.4599), valence (β = 0.2392; p < 0.05; R2 = 0.4598), and support (β = 0.3052; p < 0.01; R2 = 0.4843) contribute to explaining intention to use the platform through the partial mediating role of affective commitment (thus partially confirming Hypotheses H2d, H2c and H2d). Since skill is non-significant when paired with the mediator (p = 0.9239), Hypothesis H2a is confirmed: the mediating role of affective commitment between skill and intention to use the platform is complete. Although the mediation of affective commitment is only partial in three of the four cases, it improves the explanatory power of the model as a whole.

Table 7 reports the results for Hypothesis 3, which predicts that technology-readiness (optimism) play a moderating role between organizational and individual dispositions and affective commitment. The data only confirms Hypothesis H3c, indicating that optimism (technology-readiness) has a moderating effect on the relationship between valence (organizational and individual dispositions) and affective commitment. Specifically, the moderating effect of optimism is negative in the relationship between valence and affective commitment. Thus, given a high level of optimism, the positive effect of valence on affective commitment is lower (0.1524; 95% CI = 0.0233; 0.2542) than if the level of optimism is low (0.3122; 95% CI = 0.1484; 0.5222). In addition, the calculation of the difference between these three slopes is significant since the 95% confidence interval excludes zero (−0.0826; 95% CI = −0.2165; −0.0128). We may conclude that the moderating effect of the optimism variable decreases (index = −0.0826) the positive relationship between valence and affective commitment.

TABLE 7

| Moderating effect on mediation | Global test of mediation effect | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Variable | Perception | Effect | LLCI1 | ULCI2 | Index | LLCI | ULCI | Result |

| H3a | Skill | Minimum | 0.2281 | 0.0478 | 0.4567 | Not confirmed | |||

| Average | 0.1821 | 0.052 | 0.342 | -0.0475 | -0.2049 | 0.0575 | |||

| Maximum | 0.1361 | -0.0421 | 0.3249 | ||||||

| H3b | Support | Minimum | 0.2387 | 0.1216 | 0.3993 | Not confirmed | |||

| Average | 0.2083 | 0.1041 | 0.3589 | -0.0313 | -0.125 | 0.0462 | |||

| Maximum | 0.178 | 0.0453 | 0.3665 | ||||||

| H3c | Valence | Minimum | 0.3122 | 0.1484 | 0.5222 | ||||

| Average | 0.2323 | 0.1158 | 0.353 | -0.0826 | -0.2165 | -0.0128 | Confirmed | ||

| Maximum | 0.1524 | 0.0233 | 0.2542 | ||||||

| H3d | Appropriateness | Minimum | 0.2961 | 0.146 | 0.5046 | Not confirmed | |||

| Average | 0.2589 | 0.1268 | 0.4331 | -0.0385 | -0.1381 | 0.0197 | |||

| Maximum | 0.2216 | 0.0803 | 0.4087 | ||||||

Testing of hypothesis 3.

Lower Level Confidence Interval.

Upper Level Confidence Interval.

Confidence interval = 95%.

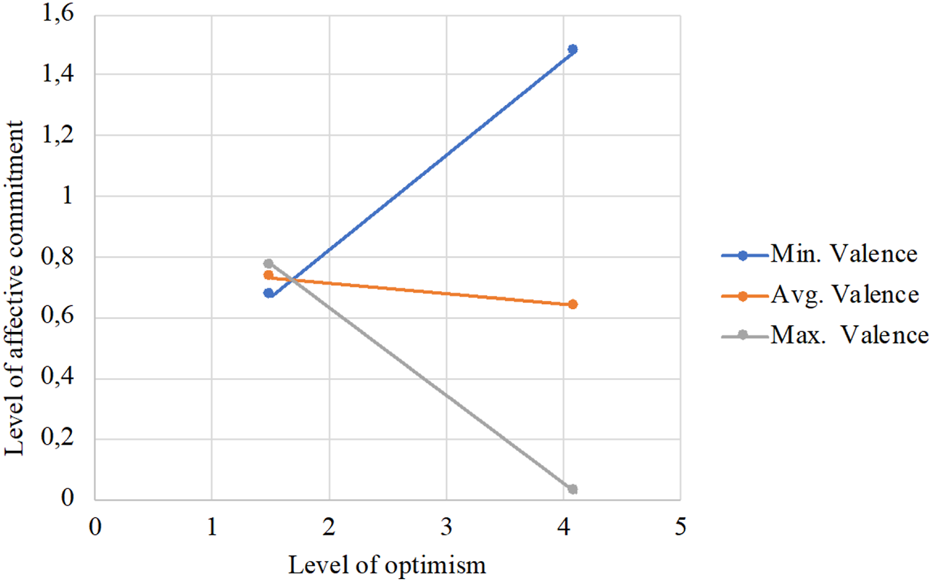

Figure 5 shows the interactions between valence, optimism, and affective commitment (Hypothesis 3c). The figure indicates that for a low level of optimism (1.5), the three valence curves (min., avg., max.) show similar levels of affective commitment (min = 0.67; avg. 0.72; max = 0.77). However, the greater the value of the optimism variable, the lower the value of the curve presenting the maximum valence level, eventually reaching zero when the optimism variable is 4.1. Given a value of 4.1 for the optimism variable, the levels of committment of the Min. Valence, Avg. Valence, and Max. Valence curves are 0.0, 0.642 and 1.47, respectively.

FIGURE 5

Visualization of the interaction between valence, optimism, and affective commitment.

Discussion

Discussion of hypothesis 1

Analysis of the data indicates that organizational dispositions (support) and individual dispositions (skill, appropriateness, valence) influence positively the intention to use the platform. The results are highly relevant to the cultural and artistic sector in suggesting that support and beliefs (appropriateness and valence) in respect of the usefulness of the platform being explain intention to use the platform more than skills. This result means that the positive vision of the platform, its usefulness, its relevance, and improvement of employment conditions are better predictors of its use than users’ digital skills. The quantitative results are corroborated by qualitative results. In the majority of interviews, respondents highlighted the need for support to a greater degree than skills. One artist noted that to join the platform, support is key: “You have to take the time to support and help people, that’s the danger with a big project like this, it’s a big challenge, you shouldn’t leave anyone behind without support (P5)”. Others noted the added value of the platform (appropriateness), as highlighted by this theater director: “Where the platform can be really beneficial is when you’re looking, say, for a designer, it can be a useful research tool. For me to use the platform, it would have to be like a mediator between artists and organizations, to be useful for finding artists in the region, that would be very beneficial (P9)”. Finally, several artists underlined the importance of improving employment conditions through the platform (valence), as illustrated by the following view: “The platform should help me feel more valued as an artist. It must allow me to present my services by being able to put up my demos, promote my activities, and distribute my CV and my photos to get new job offers and collaborate (P20).”

Despite the enthusiasm for the platform, resistance was felt during the interviews conducted in January and February 2022. As one artist put it: “Not another platform! (P5)”, while a literary director expressed her own reservations: “In terms of staffing, I wonder if there are enough people at Culture SLSJ to take on such a big project, what with all the other activities they have going on already. It’s definitely right for Culture SLSJ to take on a project like this, but I have reservations about its capacity to carry it out (P6)”. From March 2022, following the recommendations of our research team, measures were taken by Culture SLSJ to strengthen the legitimacy of the project leader and communicate the value and benefits of the platform to reduce resistance. In addition to a newsletter and publications on social networks, four “discussion day” type sessions were held to give potential users an opportunity to understand the reasons for implementing the platform. These actions had positive effects. A few months later, when we spoke to future users, one artist noted the following: “I see the project progressing, there’s potential, because the process is supported by organizations, serious people with expertise and legitimacy, and that brings a lot of seriousness to the project; everything leads me to believe there could be some interesting networking (P21)”.

Both the quantitative and qualitative analyses lead to the conclusion that the intention to use the platform is determined by organizational and individual dispositions, as suggested by Oreg et al. (2011), Vakola (2014), and Armenakis et al. (2007), with appropriateness, support, valence, and skills emerging, in order of importance, as the strongest and most positively related determinants (see Figure 4). By demonstrating that these positive relationships exist, our study confirms that the change management literature applies to the cultural sector and its digitalization.

Discussion of hypothesis 2

Affective commitment plays a positive mediating role between individual and organizational dispositions and intention to use the platform. Cunningham (2006) showed that affective commitment was more strongly correlated with change than other types of commitment (normative and continuity). The arts sector is often characterized by passion and creativity (Vandrille, 2022). During qualitative data collection, we observed that artists and cultural workers were emotionally invested in their work. Moreover, a significant proportion of participants in the interviews used the following terms when talking about their work: “attachment, belonging, creation, mutual aid, passion, motivation, openness.” In other words, affective commitment can play a key role in being closely linked to emotional attachment to change (Fedor et al., 2006; Meyer, 2016; Morin et al., 2009). These findings suggest that individuals working in the cultural and arts sector may be more sensitive to the affective dimension of their commitment compared to more normative or continuity forms, neither of which produced significant results in this study.

The mediation result suggests that affective commitment fully explains the relationship between skill and intention to use the platform. Skill refers to an individual disposition (personal perception of my skills and abilities), which may explain that skill plays a key role in affective commitment (which is also associated with a personal dimension based on individual emotions and feelings involving an emotional connection to the platform). Furthermore, this is not the case for other dispositions that refer to support, valence, and appropriateness, which have a partial effect in which affective commitment plays a less dominant role in explaining the relationship between these factors and intention to use. These variables, though important, do not depend solely on affective commitment to explain intention to use the platform. This result confirms the hierarchy of the explanatory variables of intention to use the platform (see Figure 4). More specifically, skill has the least significant effect on intention to use, although it significantly influences intention through affective commitment. Although skill may seem less influential when tested directly, it is important in the overall mediation model in explaining intention to use the platform.

It is plausible to suggest that this result is linked to the training activities and workshops provided by our research team and Culture SLSJ. With the support of experts in the digital field, training was offered between the interviews we conducted (in January and February 2022) and the distribution of the questionnaire (in September 2022). During the first interviews, we noticed concerns, as illustrated by this theater director: “It takes a human meeting another human to help people who are less digitally focused, it takes time, but I think this is where it works best (P9).” It was precisely to address these concerns that training was undertaken in the spring and summer of 2022. The results indicate that these initiatives had a positive impact on affective commitment and intention to use the platform, thus confirming the relevance of the action research approach in a change context (see Coghlan, 2011). This approach demonstrates the adaptability of the intervention to suit the needs of the setting, a basic principle of action research (Bradbury et al., 2008).

Discussion of hypothesis 3

The moderating role of optimism (technology-readiness) is significant but counterintuitive: our results indicate a negative moderating effect of optimism on the relationship between valence and affective commitment. In other words, the more the optimism variable increases, the more valence decreases its positive influence on affective commitment. Resource conservation theorists can shed interesting light on this result (Hobfoll and Shirom, 2001). According to Hobfoll (2002), people can meet the demands of their work environment by substituting resources between them. Empirical studies have shown that individual and organizational resources can be replaced by other resources (Francoeur and Paillé, 2023; Marchand and Vandenberghe, 2015).

In our study, optimism and valence can be considered interchangeable psychological resources. Optimistic individuals tend to view technology in a positive way, perceiving that it can make them more productive in their lives (Rojas-Méndez et al., 2017). Valence is the belief that platform integration can increase the sense of personal fulfillment (Armenakis et al., 2007). It is therefore plausible to assume that when optimism increases, individuals may be less dependent on valence (positive belief in the platform) to maintain their affective commitment. They can regulate their level of affective commitment through their optimism because they have a positive view of technology, regardless of valence. It is also possible that when optimism is high, individuals have excessively high expectations about the valence of the platform (i.e., they expect it to be extremely positive). When expectations are not met, the result can be a loss of psychological resource since individuals may feel disappointed or disillusioned, which may explain the decrease in valence on affective commitment when optimism is high. At a lower level of optimism, individuals may have lower expectations, meaning that their optimism resource is not threatened by unrealistic expectations. Therefore, valence and optimism can be seen as resources that can substitute for each other (Hobfoll, 2002), with both indicating a positive perception of change.

Synthesis of the results

Table 8 illustrates the integration of the qualitative and quantitative findings through a triangulation process and provide a guide to good practice for cultural and artistic organizations wishing to undertake a digital transition initiative. The qualitative data confirm and enrich the quantitative analysis by mapping the key variables of the theoretical model (beliefs, support, skills, optimism, commitment, and intention to use) onto Lewin’s (1947) three-step change. Decrystallization (step 1) requires banking on individuals’ positive beliefs toward the platform to call into question established behaviors. When individuals feel supported, competent, and comfortable with technology, they are more likely to develop an emotional attachment to the platform. The introduction of the change must enable the development of affective commitment to adopt new behaviors (step 2). Recrystallization should show how individual, organizational, and technology-readiness dispositions can ensure the integration of new behaviors and sustainable mobilization in the cultural sector measured by the intention to use the platform in our study (step 3).

TABLE 8

| Steps | Variables | Verbatims | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beliefs (valence and appropriateness) | Appropriateness Where the platform can be really beneficial is when you’re looking, say, for a designer, it can be a useful research tool. For me to use the platform, it would have to be like a mediator between artists and organizations, to help us find artists in the region, that would be very beneficial(P9). Valence The platform should help me to feel more valued as an artist. It must allow me to present my services by being able to put up my demos, promote my activities, and distribute my CV and my photos to get new job offers and collaborate(P20). Resistance It’s difficult to convince people of its usefulness. Some wonder if it’s the right way to do things(P3). | Challenge traditional ways of doing things Identify gaps in old working methods and show that digital transformation is necessary to increase the visibility of artists and cultural organizations as well as the accessibility of their work. | |

| Unfreezing | Support | ...we need to support them...(P4). You shouldn’t leave anyone behind without support(P5). We have to help each other along, you can’t just tell people to sort things out themselves(P7). ...there needs to be support and help for the people who need it(p8). It takes a human meeting another human to help people who are less digitally focused, it takes time, but I think this is where it works best(P9). | Offer support Cultural leaders, whether artists or museum directors should play an active role in supporting the technological change and becoming ambassadors in the community. Set up workshops and discussion groups Promote the exchange of ideas between different cultural workers (writer, actor, museologist) to identify concerns over, and the benefits of, the technological change. |

| Skills | There are many artists who are self-taught, they don’t have the same skills...(P4). Digital skills will be important to develop...I’m thinking about training, it’s essential(P18). | Provide training Personalize training according to the specific needs of cultural groups, such as through virtual promotion of works and digital data security. These new skills can encourage greater adoption of technology. | |

| Optimist (Technology-readiness) | It’s useful for building bridges ... and to feel more connected to others(P7). The platform could help us promote ourselves and get more contracts(P9). It can give me more freedom in my work(P22). Resistance ...Many people are afraid of digital tools(P4). Not another platform!(P5). There’s resistance to digital technology(P10). | Justify the digital transformation Explain how the digital tool can help artists reach a wider audience, promote their work more effectively, and diversify their sources of income. | |

| Change | Commitment | Artists seem genuinely open, but it depends on how much time it will take them(P7). ...You have to engage people in the process from the start, it’s then easier to get buy-in(P8). This project motivates me, it’s inspiring for our community...(P9). ...Integrating the platform is a good thing !(P11). Resistance I don’t see the need for such a platform(P6). | Build in appropriation time Hold demonstration sessions devoted to the digital tool and provide opportunities to interact directly with project leaders to allow questions to be asked in real time and enable adaptation. |

| Refreezing | Intention to use | It would be great to have a space where we can share what worked for us and learn from other’s...(P9). Oh, yes absolutely, I’d love to use it [the platform](P23). Is it possible to know if the platform helps us get more collaborations?(P16). I’d like to know how many artists have benefited from it... Feedback is essential...(p19). I’m not sure if the project might lose steam, but I think the more we get writers involved in creating and sharing, the more it’ll really reflect our Saguenay identity(P18). We often lose the momentum and excitement from the beginning; we should find ways to keep collaborating(P27). | Consolidate acquired knowledge Organize cultural days dedicated to technology to share good practice. Artists can discuss new contracts they have secured, or present digital works created using the platform. Assess the impact Assess the level of user satisfaction with the digital tool, focusing on how it has contributed to the promotion of art and culture. Encourage users to provide feedback on their experience with the technology. Mobilize the cultural sector Engage users in the creation of instructive content (on a continuous basis) to create a culture of innovation, e.g., via a comic strip on the opportunities of the technological transition or a poetry reading on the benefits of a digital tool. |

Lewin’s change model applied to a technological change in the arts and cultural sectors.

Theoretical contribution

First, the strength of this study lies not only in its mixed-method design (five methodological approaches) but also in the integration of these methods through triangulation to develop new and credible conceptual insights into digital change in the cultural sector (see Denzin, 2017; Greene, 2007). Each of the methodological approaches used was adopted to complement and feed off the others, as suggested by Shah and Corley (2006). By combining qualitative depth and quantitative testing, the study generated an empirically grounded framework that links change management theories to creative work realities. We gained a detailed understanding of how individual (beliefs, skills), organizational (support), and technology-readiness (optimism) dispositions interact during a process of digital transformation in an artistic context. In this sense, our study identifies the determinants that explain why artists and cultural actors intend to use a digital platform, variables that have been little explored in previous studies on the digital transformation of culture and art. Most post-COVID-19 research has focused on the consequences of digitalization (opportunities and challenges) rather than on its antecedents (e.g.: Koshelieva et al., 2023). For example, Leguina et al. (2025) analyze how audiences evaluated online theatre experiences and their potential impact on future behavior while Szostak and Sułkowski (2024) assess how the form of participation (in-person or digital) affects the quality of artistic experience. We therefore seek to contribute to the broader debate on digital transformation in the arts and culture sector by clarifying how change management variables influence creative environments.

Second, our study stands out by transferring Lewin’s change management model (Lewin, 1947) to an artistic and cultural context with a view to analyzing a digital transformation process. We align with Bakari et al. (2017), who reinterpreted Lewin’s three-step framework in the public sector by integrating management variables such as readiness, commitment to change, and support. Despite the criticisms of Lewin’s theory (see Burnes, 2020), our results confirm that his theory remains relevant when operationalized through empirically measurable variables. This extends the model by showing that digital transformation in the cultural field is not a linear sequence of unfreezing–change–refreezing, but rather an iterative process shaped by emotional investment and learning within decentralized structures.

Third, our study targeted a population that has been relatively little studied in management, i.e., artists and self-employed workers including actors, writers, painters, and sculptors (Derouin-Dubuc, 2022; Francoeur, 2019). This group operates outside conventional organizational hierarchies (Haunschild and Eikhof, 2009) which makes it particularly relevant for examining how change occurs in the absence of formal structures or managerial control. By analyzing how cultural actors experience technological change, we extend the scope of change management research to art and cultural sector, where traditional managerial levers can be replaced by peer support, beliefs and emotional engagement. This theoretical reframing thus bridges change management, digitalization and cultural management, providing a conceptual lens to understand digital adoption in contexts where professional identity, creativity, and autonomy are central drivers of transformation.

Practical contribution

Our study demonstrated the positive impact of action research in the context of a technological transformation process within creative context. While action research has often been used in areas such as education (Glanz, 2014), development (Reason, 2015), and health (Stringer and Genat, 2004), it has been less commonly applied to cultural organizations in research to date. Beyond documenting a successful intervention, the findings identify concrete mechanisms that can guide practitioners in supporting digital change, namely, early engagement of artists, iterative co-design of digital tools, and targeted capacity-building through training and mentoring. Between the interviews (January–February 2022) and the visits to the cultural and artistic sites (July 2022), we observed a measurable shift in participants’ attitudes: artists and cultural workers became more receptive to the digital platform once they were actively involved in the co-creation process. These results confirm the effectiveness of participatory and iterative change management approaches inspired by Lewin (1947) but adapted to the cultural and artistic settings (Adam-Ledunois et al., 2019).

Another notable result is that all the artists interviewed enrolled on the digital platform, highlighting the importance of integrating potential users into a pre-change process to maximize acceptance and adoption of new technologies as demonstrated by many researchers since Lewin’s (1947) foundational studies (Bareil et al., 2020; Collerette et al., 2021). By linking this outcome to affective commitment, the study offers actionable insights for cultural managers seeking to foster sustainable digital transformation. The active participation of recipients (interviews, training, workshops) helped promote co-construction of knowledge, reduce resistance, and strengthen affective commitment, as demonstrated by studies in change management (e.g.,: Oreg, Vakola and Armenakis, 2011).

Limitations and future research avenues

Our study is not without limitations. First, we did not distinguish between the categories of workers surveyed. We acknowledge that artists, self-employed workers in the cultural sector, and representatives of artistic and cultural organizations and institutions are likely to have different work experiences. Given the size of our quantitative sample (n = 70), we were not able to discriminate between the different categories quantitatively. We suggest qualitative data collection to provide additional insights to determine if there are distinctions between the people surveyed (Huberman and Miles, 2002; Tracy, 2010). Second, while we measured perceptions of the use of the platform and its potential, it would be interesting to determine whether the change really allows for new collaborations and professional opportunities by measuring the number of new contracts awarded via the platform. Third, although we adopted a mixed-methods approach to enrich our understanding of the phenomenon, the integration of qualitative and quantitative data remains limited, partly because of the size of our sample. Future studies could strengthen methodological triangulation by applying longitudinal designs to better capture the evolution from intention to behavior over time, which could help reduce the well-documented intention–behavior gap (Sheeran and Webb, 2016). Fourth, the study was mainly based on a specific case, which could limit its generalizability. Case studies relate to a particular context and are not intended to represent the entire population (Yin, 2003). Therefore, it is important to interpret the results in relation to the specific context in which the study was conducted. Nevertheless, the proposed recommendations can serve as a guide for other cultural and artistic organizations wishing to implement a digital tool and encourage future users to change their habits and behaviors.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Polytechnique Montreal University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

VF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. JM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. CB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Validation, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by the Canadian organization Mitacs (15 000 $), which enables effective collaboration between universities and organizations.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the reviewers and the editor for their insightful comments, which contributed to improving this article. We also thank former director of Culture Saguenay Gabrielle Desbiens and the staff for their support throughout this project, especially Vanessa Tremblay, Caroline Marcel, and Abdourakhmane Fall. We further extend our thanks to Carl St-Pierre for his statistical support.

Conflict of interest

The authors(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ejcmp.2025.15467/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^https://reseau.cultureslsj.ca/

2.^Before collecting data, a certificate was issued by the Research Ethics Committee of Polytechnique Montreal (CER-2223-10-D).

3.^The respondents’ status is the only available information about the population that allows testing representativeness using a chi-square test, as the other variables (e.g., postal code) are confidential.

4.^Although the mediating role of normative commitment and continuity was measured, the results are not reported since it was not significant.

5.^See the models developed for the MACRO process at http://afhayes.com.

References

1

Adam-LedunoisS.CanetÉ.DamartS. (2019). “Recherche collaborative ou comment comprendre le management en le transformant,” in Méthodes De Recherche Qualitatives Innovantes (Paris: Economica).

2

AdelmanC. (1993). Kurt lewin and the origins of action research. Educ. Action Res.1 (1), 7–24. 10.1080/0965079930010102

3

ArmenakisA. A.BernerthJ. B.PittsJ. P.WalkerH. J. (2007). Organizational change recipients’ beliefs scale: development of an assessment instrument. J. Appl. Behav. Sci.43 (4), 481–505. 10.1177/0021886307303654

4

BakariH.HunjraA. I.NiaziG. S. K. (2017). How does authentic leadership influence planned organizational change? The role of employees’ perceptions: integration of theory of planned behavior and lewin’s three step model. J. Change Manag.17 (2), 155–187. 10.1080/14697017.2017.1299370

5

BareilC.SavoieA.MeunierS. (2007). Patterns of discomfort with organizational change. J. Change Manag.7 (1), 13–24. 10.1080/14697010701232025

6

BareilC.CharbonneauS.BaronA. (2020). Voyage au cœur d’une transformation organisationnelle: Récit et guide pas à pas, JFD. Montreal: Editions.

7

BeerM. (2021). Reflections: towards a normative and actionable theory of planned organizational change and development. J. Change Manag.21 (1), 14–29. 10.1080/14697017.2021.1861699

8

BorodakoK.BerbekaJ.RudnickiM.et ŁapczyńskiM. (2023). The impact of innovation orientation and knowledge management on business services performance moderated by technological readiness. Eur. J. Innovation Manag.26, 674–695. 10.1108/ejim-09-2022-0523

9

BradburyH.MirvisP.NeilsenE.PasmoreW. (2008). “SAGE handbook of action research,” in Handbook of Action Research. Editors ReasonP.BradburyH. (Montreal: Publications LDT), 77–92.

10

BraunV.ClarkeV. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol.3 (2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

11

BurnesB. (2020). The origins of lewin’s three-step model of change. J. Appl. Behav. Sci.56 (1), 32–59. 10.1177/0021886319892685

12

BurnesB.JacksonP. (2011). Success and failure in organizational change: an exploration of the role of values. J. Change Manag.11, 133–162. 10.1080/14697017.2010.524655

13

Canada Council for the Arts (2021). Façonner un nouvel avenir plan stratégique 2016- 2021. Available online at: www.conseildesarts.ca.

14

CoghlanD. (2011). Action research: exploring perspectives on a philosophy of practical knowing. Acad. Manag. Ann.5 (1), 53–87. 10.5465/19416520.2011.571520

15

ColleretteP.LauzierM.SchneiderR. (2021). Le Pilotage Du Changement - 3E Édition. Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

16

CorbièreM.NadineL. (2020). Méthodes qualitatives, quantitatives et mixtes: Dans La Recherche En Sciences Humaines, Sociales Et De La Santé. Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

17

CôtéM.-A. (2022). Une Nouvelle Vitrine Numérique Pour Le Milieu Culturel Régional. Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean, QC: Le Quotidien. Available online at: https://www.lequotidien.com/2022/10/26/une-nouvelle-vitrine-numerique-pour-le-milieu-culturel-regional095976e90ccd9a772c34a9e5bcc8c936/.

18

CultureSLSJ. (2021). À propos. Cult. Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean. Available online at: https://cultureslsj.ca/a-propos/.

19

CummingsS.BridgmanT.BrownK. G. (2016). Unfreezing change as three steps: rethinking kurt Lewin’s legacy for change management. Hum. Relat.69 (1), 33–60. 10.1177/0018726715577707

20

CunninghamG. B. (2006). The relationships among commitment to change, coping with change, and turnover intentions. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol.15 (1), 29–45. 10.1080/13594320500418766

21

DenzinN. K. (2017). The Research Act: a Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. 4th ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

22

Derouin-DubucL. D. (2022). L’action stratégique des artistes en arts visuels et de leurs collectifs en contexte de précarité du travail: quel(s) rôle(s) pour les centres d’artistes autogérés situés à Montréal ?Thèse Dr. Univ. Montréal, École relations Ind.

23

FedorD. B.CaldwellS.HeroldD. M. (2006). The effects of organizational changes on employee commitment: a multilevel investigation. Pers. Psychol.59 (1), 1–29. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00852.x

24

FordJ. D.FordL. W.D’amelioA. (2008). Resistance to change: the rest of the story. Source Acad. Manag. Rev.33 (2), 362–377. 10.5465/amr.2008.31193235

25

FrancoeurV. (2019). Sciences Et Arts. Transversalité Des Connaissances. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval.

26

FrancoeurV.PailléP. (2023). Trop fatigué(e)s pour être écoresponsables … à moins d’être soutenu(e)s. Manag. Int.27, 118–130. 10.7202/1098926ar

27

FrancoeurV.PassalacquaA. (2023). Une Transformation Numérique Au Cœur De Culture Saguenay – Lac-Saint-Jean. Montréal, QC: Presses Internationales Polytechnique.

28

GagnonY. C. (2008). Les trois leviers stratégiques de la réussite du changement technologique. Télescope, Rev. D’analyse Comparé En. Adm. Publique14 (3).

29

GagnonY.-C.PréfontaineL. (2007). Gérez Un Projet De Changement Technologique. Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

30

GersonK. (2020). “Constructing an interview guide: creating a flexible structure,” in The Science and Art of Interviewing. Editors GersonK.DamaskeS. (Oxford University Press).

31

GlanzJ. (2014). Action Research: an Educational Leader’s Guide to School Improvement. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC.

32

GonzalezK.PortocarreroF. F.EkemaM. L. (2023). Disposition activation during organizational change: a meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol.76, 829–883. 10.1111/peps.12513

33

GreeneJ. (2007). Mixed Methods in Social Inquiry. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

34

GuestG.NameyE.ChenM. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PloS One15 (5), 1–17. 10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

35

HairJ. F.BlackW. C.BabinB. J.AndersonR. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

36

HaunschildA.EikhofD. R. (2009). Bringing creativity to market: actors’ labour markets and the institutionalization of artistic work. Organ. Stud.30 (9), 1309–1331.

37

HayesA. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford publications.

38

HerscovitchL.MeyerJ. P. (2002). Commitment to organizational change: extension of a three-component model. J. Appl. Psychol.87 (3), 474–487. 10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.474

39

HobfollS. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. General Psychol.6 (4), 307–324. 10.1037//1089-2680.6.4.307

40

HobfollS. E.ShiromA. (2001). “Conservation of resources theory: applications to stress and management in the workplace,” in Handbook of Organizational Behavior. Editor GolembiewskiR. T. (New York, NY: Dekker), 57–80.

41

HolstC.Bekmeier-FeuerhahnS. (2024). Between institutional scaling and artistic probing: how traditional performing arts organizations navigate digital transformation. J. Organ. Change Manag.38 (8), 234–253. 10.1108/jocm-06-2025-0494

42

HoltD. T.ArmenakisA. A.FeildH. S.HarrisS. G. (2007). Readiness for organizational change: the systematic development of a cale. J. Appl. Behav. Sci.43 (2), 232–255. 10.1177/0021886306295295

43

HornungS.RousseauD. M. (2007). Active on the job —proactive in change: how autonomy at work contributes to employee support for organizational change. J. Appl. Behavioral Sci.43 (4), 401–426.

44

HubermanM.MilesM. B. (2002). The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

45

HussainS. T.LeiS.AkramT.HaiderM. J.HussainS. H.AliM. (2018). Kurt Lewin's change model: a critical review of the role of leadership and employee involvement in organizational change. J. Innovation and Knowl.3 (3), 123–127. 10.1016/j.jik.2016.07.002

46

IslamM. N. (2023). Managing organizational change in responding to global crises. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell.42 (3), 42–57. 10.1002/joe.22189

47

JournéB. (2018). “Collecter les données par l’observation,” in Méthodologie De La Recherche En Sciences De Gestion: Réussir Son Mémoire Ou Sa Thèse. Editors Gavard-PerretM.-L.GottelandD.HaonC.JolibertA. (Paris: Pearson), 129–174.

48

JudgeT. A.HigginsC. A.ThoresenC. J.BarrickM. R. (1999). The big five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Pers. Psychology52 (3), 621–652. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1999.tb00174.x

49

KoshelievaO.TsyselskaO.KravchukO.BuriakB.MiatenkoN. (2023). Digital transformation in culture and art: exploring the challenges, opportunities, and implications in cultural Studies. Res. J. Adv. Humanit.4 (3), 41–55. 10.58256/rjah.v4i3.1236

50

KotterJ. P. (2007). “Leading change: why transformation efforts fail,” in On Change Management. Harvard Business Review.

51

KriefN.ZardetV. (2013). Analyse de données qualitatives et recherche-intervention. Rech. Sci. Gest.95 (2), 211–237. 10.3917/resg.095.0211

52

LeguinaA.ManninenK.MisekR. (2025). Beyond the “substitution effect”: the impact of digital experience quality on future cultural participation. Cult. Trends34 (1), 105–124. 10.1080/09548963.2023.2295883

53

LescarbeauR. (2010). L’enquête Feedback. Montréal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

54

LewinK. (1947). Frontiers in group dynamics. Hum. Relat.1 (1), 5–41. 10.1177/001872674700100103

55

LewinK. (1952). “Group decision and social change,” in Readings in Social Psychology. Editors SwansonG. E.NewcombT. M.HartleyE. L. (New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston).

56