Abstract

This paper explores the systematisation behind the creation of digital fashion archives, focusing on the complex relationship between archival methods and matters, labour, and technological interfaces. By initially distinguishing between digitised and born-digital archives, the study highlights the heterogeneous nature of contemporary fashion archiving practices and the challenges they pose in terms of materiality, preservation and curation in the digital age. Drawing on the unexplored case study of Promemoria Group, an Italian company specialising in the digitisation of fashion archives and their management, the research investigates the invisible labour involved in digital content production. Through a semi-structured interview with Cecilia Botta and Nicoletta Esposito from Promemoria, the paper presents the premises and practices of digitising fashion archives today, exploring the specific techniques of curation, mediation and storytelling developed by this agency. The findings reveal how technological infrastructures and human labour together shape the construction, accessibility, and perception of fashion heritage in the digital age.

Introduction

In recent years, the global discussion around digital archives gained increasing relevance within the field of fashion, becoming a central topic not only in terms of the narration of a collective history of fashion and the preservation of a cultural heritage, but also in terms of construction of brand identity, of communication and curatorial practices and, therefore, public engagement. Consequently, the topic gained partial recognition within the field of fashion studies and archival studies (Pecorari, 2019; Peirson-Smith and Smith, 2021; Vandi, 2023; Vacca, 2025), where researchers started to explore how fashion archives play a fundamental role in institutional, corporate, and independent contexts, thereby enabling new forms of access and circulation of fashion knowledge.

Globally, the turn to digitisation has transformed the visibility and circulation of fashion heritage. Major institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art now offer expansive, browsable online collections that make decades of material culture discoverable to wide publics. Moreover, in Europe, heritage has also been mobilised as a political and identity-making resource–visible in annual initiatives such as the European Heritage Days or the Italian Notte degli Archivi – while simultaneously being absorbed into commercial logics, most visibly within the luxury sector. In fashion, public museums and libraries continue digitising their collections, while private houses invest in a continuous institutionalisation of their pasts through dedicated heritage departments and blockbuster exhibitions. Clear examples are the recent platform Armani/ARCHIVIO or the opening of La Galerie Dior, Mugler and Schiaparelli exhibitions at MAD Paris, or even by sponsoring certain maison-driven access days (for instance LVMH’s Journées Particulières). The result is a dense ecology in which copyright and brand protection sit alongside curatorial labour and creative strategies. This scenario thus raises urgent questions about access, authorship, and the balance between public value and private control in the digitised remembering of fashion.

In the Italian scenario, certain public entities began to respond to this trend, investing in the development of systems such as SIUSA (Sistema Informativo Unificato per le Soprintendenze Archivistiche1), an Italian national database that provides centralised access to data of non-state public and private archival holdings preserved outside the State Archives (Bondielli, 2001). Developed by Direzione Generale Archivi2 in collaboration with Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, SIUSA was launched in 2005 to enhance the protection, accessibility, and research of Italy’s archival heritage (Bondielli, 2001). More specifically, in the field of fashion, ANAI (Associazione Nazionale Archivistica Italiana3), with the support of the General Directorate for Archives, developed the Portale degli Archivi della Moda del Novecento4 in 2011, as part of the Sistema Archivistico Nazionale5, intending to gather, preserve, and make accessible, to both specialists and the general public, a wide array of archival, bibliographic, iconographic, and audiovisual sources related to Italian fashion (Ministero della Cultura, 2025). The emergence of these state-funded projects and digital realities not only evidence that archives in Italy are gaining recognition both within specialists of the field and outside, but also that Italian fashion heritage is being reassessed via a digitising process. Its cultural and economic significance is today recognized as an industry per se, and its digitisation has become a fundamental engine of this process.

Building from this scenario, this research digs deeper into further developments and successful realities that have populated the digital archival system in Italy. This study originates from a contemporary attention towards the increasing formation and dissemination of fashion archives and their consequent effects on the idea of fashion and its historiographies. For example, Pecorari explored the transformation of physical fashion archives into digital and the effects of these practices, highlighting how certain fashion institutions worldwide have opened towards initiatives of digitisation (Pecorari, 2019, p. 3). The attention has focuses on an international and vast action of digitising fashion archives: from public museums like the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which have digitised and published online their collections, to private publishing companies like Vogue US or Harper’s Bazaar, which have shared their digital issues on certain online library servers such as ProQuest or Bloomsbury Fashion Central. In these processes, Pecorari recognised a lack of attention given by scholars to such a tendency stressing the necessity to reflect “on practices of digitisation of archives and museum collections; the use of the digital in curatorial practices; the politics of online archives and digitisation; the role of digital archives in academic research” (Pecorari, 2019, p. 4).

This paper builds on this initial gap. While the proliferation of digitised and born-digital archives has continued to expand and to generate new opportunities for the industry of heritage (Hewison, 1987), a systematic analysis of these digital practices is still lacking. With the ever-evolving technological innovations and brands’ investments in digital internal systems of archiving data, the nature and purpose of these diverse archives are constantly being rethought and reimagined. Thus, there is still a need to address how fashion is represented and structured within digital archives; what infrastructures (both technical and human) underpin these practices; and how questions of authorship, materiality, and authority emerge in the digital realm.

Materials and methods

This paper begins to explore these issues, addressing the following questions: what practices define a digital fashion archive today? How can their interfaces, structures, and cultural meaning be systematically understood? What new professional figures are emerging today in this field? How do labour, curation, and technology interact in shaping them? The aim is to define the conceptual boundaries that lie between digital fashion archives based on their typology (digitised and born-digital ones), while exploring how they reconfigure relationships between heritage, labour, and technology in contemporary practices. This article explores these issues, urging a discussion on the contemporary emergence of new practices and skills concerning the creation and digitisation of fashion archives. Following the idea of Laurajane Smith’s seminal volume Uses of Heritage (2006), we argue that fashion heritage must be understood as a cultural and social practice with a series of protocols and rules that construct the practice and discourse around it (Smith, 2006, p. 13). “There is no such thing as heritage” (p. 11), she writes, unless we recognise it as a socially constructed process shaped by political, institutional, and cultural forces. From this standpoint, heritage is not something merely to be discovered or preserved, but something that is actively produced through expert knowledge systems, technological software, policy frameworks, and institutional practices (p. 13). Thus, the management and conservation techniques undertaken by heritage professionals are not merely neutral operations but act themselves as meaning-making practices, shaped by and reinforcing the discourses in which they are embedded (p. 88).

This article draws on these theoretical premises to unpack the hidden labour, actors and technical mechanisms at play in both the discourse and practice of fashion heritage, focusing on the case of the Promemoria Group, an Italian Turin-based company created in 2011. Created by Andrea Montorio and Gisella Riva, Promemoria is a leading group in the organisation and digitisation, and subsequent preservation and valorisation process behind major private and public archives in various fields (Montorio, 2021). The case of Promemoria Group allows for an in-depth exploration of how archival practices are systematised in the digital domain, how labour and metadata can be structured, and how the conceptualisation of interface design shapes access and meaning to archival materials. This case study allows us to unpack the hidden mechanisms behind the industry of digitising archives while stressing the importance of understanding the processes, schemes, and systematised methods of approaching the digital realm of fashion archives.

Between physical and digital: re-defining fashion archives

Fashion archives can be categorised in various ways due to their institutional typology. They can be generally divided into public archives – whether national, regional, or city managed – or private ones – whether belonging to a fashion brand or designer, a foundation, or a single person. Moreover, the categorisation of fashion archival content belonging to both categories can also be split into two major groups: physical items – meaning garments, accessories, photographic material, textiles, sketches and drawings, ephemera and documentation in general – or immaterial ones – such as digitised or born-digital formats of images and videos, metadata, CSM systems, audio formats, and eventually oral histories.

The digital turn, however, has naturally made a radical impact on the definition of fashion archives, starting from the constantly evolving formats and typologies of materials that expand the boundaries of what an archive might accommodate, and which are crucially dependent on technological innovation. A first ontological distinction can be found between digitised archives – collections originally composed of physical objects that have been transformed into digital form through processes such as scanning, photographing, or recording – and born-digital archives – collections originated entirely in digital formats, without any prior physical existence. The former involves practices of imaging and metadata generation, a shift from fashion object to metadata that consequently consists of a dematerialisation of meaning of the physical archive as well (Franceschini, 2019). Therefore, this new landscape is marked by a newly found material heterogeneity and epistemic transformation. Garments might coexist with 3D renderings, promotional videos, oral histories, and even sensory simulations like sound or smell (Vandi, 2023). Moreover, both these typologies often seem to reach a wider public than the one usually permitted to access the physical archive, as they are disseminated not only through dedicated websites and platforms but also through social media pages. While promoting an apparent democratisation of access towards archival material, these profiles are also expanding the definition of what can be considered a fashion archive (Pecorari, 2019; Franceschini, 2019). Finally, due to the subsequent popularisation of social media pages that reappropriate the lexicon and ontology of the fashion archive, certain born-digital initiatives can support participatory and decentralised models of archiving, challenging traditional hierarchies and expanding curatorial frameworks (Trame, 2023). Such developments reshape the archive’s role from a static repository to a dynamic interface for access, reinterpretation, and cultural negotiation. Whether digitised or born-digital, these archives are shaped by three main core characteristics: material heterogeneity, technological mediation, and interface dependence. These features distinguish them from their analogue counterparts and influence how fashion heritage is preserved and interpreted. Speaking about issues of control and access to archival material, Pecorari places the digital in apparent contrast to traditional notions of exclusivity, secrecy, and material uniqueness usually about physical repositories of archival fashion, introducing a logic of spectacle and accessibility related to heritage materials: “The digital apparently inverts the archival idea of uniqueness and rareness, evoking a sense of unlimited access and participation. The Internet has, in fact, extended the experience of the fashion museum and, for example, the confidentiality behind the making of an exhibition” (Pecorari, 2019, p. 8). Thus, the digital does not merely replicate the archive’s traditional role as a site of conservation; rather, it reconfigures it as a space of visibility, dissemination, and audience engagement. However, the apparent access promised by online platforms seems to mask deeper asymmetries – what becomes digitised is not always determined by curatorial intent but often by economic funding and technological infrastructures. The digital archive, while apparently providing a more democratic approach to objects and items, mimics the dynamics of the physical one when regulated by public or private infrastructures.

While fashion’s entry into museum spaces was once legitimised through its rarity and material prestige, the digital archive performs an inversion of value: heritage becomes accessible not through contact with the object, but through its digital representation. This shift repositions the archive as an interface, both technological and cultural, one that stages and glamorises archival labour, reframing curatorial practices as part of a broader “economy of culture” (Pecorari, 2019, p. 5). Furthermore, Franceschini (2019) analyses the implications of digitisation in the fashion archive, framing it as a shift from the material object to metadata, as previously anticipated when defining the typologies of archives. She highlights that the digital archive no longer merely houses objects but operates as a system of documentation, privileging visual and textual information. This evolution marks a return to the primacy of the document, where the object is subsumed into a network of metadata. Such a framework challenges traditional interpretive methodologies in fashion studies, demanding new approaches that consider the archive as both technological infrastructure and epistemological tool: “The nature of archives therefore is changing, becoming more and more open and wide-reaching in terms of making space but also – and more interestingly – in terms of defining time” (Franceschini, 2019, p. 72). Investigating three different types of digital archives (‘Open Fashion’ by the MoMu fashion museum, ‘Europeana Fashion’, and the Armani/Silos Digital Archive) Franceschini shows how digital fashion archives are to be considered also as sites of negotiation between materiality and code, between curatorship and automation, and between visibility and exclusion. As such, Franceschini calls for a rethinking of fashion historiography considering the digital’s remediating force, where access, classification, and the aesthetics of the platform all participate in the reconstruction of fashion’s cultural memory.

The analysis of day-to-day practices behind the creation of a digital archive is therefore central to be analysed when we attempt to fully understand the systematisation of a digital archive. For example, we should consider how software and datasets create a homogenisation of content and a selective visibility governed more by funding priorities than by scholarly or curatorial frameworks. This raises crucial questions around institutional power, access, and control – echoing Foucauldian critiques of physical archives. As Pecorari questions: “What is not digitalized from museum and archive collections? And how does this apparent access affect issues of historical practice?” (Pecorari, 2019, 22). Daniela Calanca (2020) also addresses the limitations of conventional metadata structures in capturing the complexity of fashion heritage. Building on Stefano Vitali’s reflections on digital cultural heritage, she critiques the incongruence between digital data systems and the epistemic needs of fashion archives, arguing that fashion’s temporal fragmentation and relational nature require more than mere aggregation of descriptions or visual reproductions (Calanca, 2020, p. 12). She calls for a re-description of archival data that acknowledges the immaterial dimensions of fashion artefacts – context, circulation, use, presence in an institution, but also interpretation, references to social practices, geographical movements, and historical reactivations – elements that often fall outside traditional cataloguing practices. In this view, digital collections should not just keep a digital record of the object but actively enrich it with additional knowledge that emerges from its broader cultural meaning (Calanca, 2020, p. 14). This shift not only responds to the disaggregated nature of digital data in fashion but also reclaims the research value of context-specific and time-sensitive knowledge.

Whilst these considerations can be applied to multiple typologies of digital archives (public or private digitised collections and born-digital ones), Vacca (2025) argues that corporate fashion archives could be seen as forms of “living cultural heritage” to describe the heritage they behold into four interpretive models: the heritage narratives model, centred on marketing strategies that position the archive as a self-celebratory tool, enhancing brand identity through museums, exhibitions, and storytelling (Vacca, 2025, p. 8); the heritage-in-process model, which values craftsmanship and historical know-how as active resources in contemporary design and sustainable innovation (Vacca, 2025, p. 9); the immersive heritage experience, where archives are augmented through multimedia and multichannel strategies, expanding objects into virtual and processual dimensions (Vacca, 2025, p. 10); the disruptive heritage model, which redefines brand heritage as a relational practice embedded in broader cultural and economic ecosystems, involving both internal actors and external publics (Vacca, 2025, p. 11).

In this framework, the archive becomes a performative tool for constructing authenticity and projecting desirable lifestyle narratives, a perspective that will be later taken into consideration when analysing the case study of Promemoria Group that, at once, act as sites of celebration, research, and creative projection that propose the archive as an active strategic asset, capable of shaping the brand’s future.

Moreover, when considering only digital-born archives, the scenario takes a further development. The emergence of born-digital archives – such as those developed on social media platforms – blurs the line between personal memory and institutional historiography (Pecorari, 2019, p. 19). These digital spaces foster a more inclusive and participatory model of fashion memory, challenging Western-centric and industry-focused narratives historically embedded in physical archives: “The possibility of downloading, interacting with and manipulating the digital image of a historical object illustrates the coexistence of a personal, individual ‘unofficial’ memory with an official institutionalized history” (Pecorari, 2019, p. 20). However, they also introduce ephemerality and instability, raising questions about the management and conservation of digital content. While digitisation opens overlooked geographies and temporalities of fashion, it also demands a “constant archival vigilance” (Pecorari, 2019, 16), as many initiatives lack a long-term strategy for maintaining digital heritage. Angelica Vandi (2023) also addresses the unique role of digital archives and platforms in reshaping how fashion is firstly documented but then curated and disseminated too. The digitisation of collections, she argues, entails “incorporating technological solutions to reorganise archival methods and acquisition practices,” as well as “rethinking fashion curatorial practices with new modes that expand and hybridise the physical and digital dimensions of fashion cultural heritage” (Vandi, 2023, p. 157). Central to this process is the increasing importance of multimodal and interactive approaches. Digital technologies empower curators and users alike to explore objects’ “tacit knowledge” and to unveil their “interconnections with external facts and other bodies of cultural data”, ultimately enabling more immersive and extended experiences (Vandi, 2023, p. 157). This multimodality allows for an augmented interplay between digital records and physical artefacts, fostering a holistic experience that integrates narrative, interpretation, and sensory engagement. This perspective foregrounds the dual role of digital fashion archives: not only do they safeguard historical identity codes, but they also enable forward-looking experimentation, offering new design pathways and contributing to innovation in the cultural and creative industries (Vandi, 2023, p. 157), two key aspects in the discussion around the case of Promemoria Group.

A case study: promemoria group

This section constitutes the analytical core of the paper. It is structured as a semi-structured interview conducted with two key figures of Promemoria Group. The Turin-based company specialises in the digitisation, preservation, and strategic valorisation of archival materials across a range of cultural and industrial domains (Promemoria, n.d.). We conducted interviews with Cecilia Botta (Head of Memories) and Nicoletta Esposito (Head of Communication). These interviews took place on May 7th, 2025 via a zoom meeting with the ambition of learning information about the making of the archives for brands and the digital systems offered by the company. These interviews offered critical insight into how contemporary archival practices are conceptualised and systematised within digital infrastructures, shedding light on how metadata, labour, and interface design work together to shape archival knowledge and its circulation. The analysis of the case study is thus only taking into consideration one type of digital archive: the digitised one – from physical to digital format – both public and private.

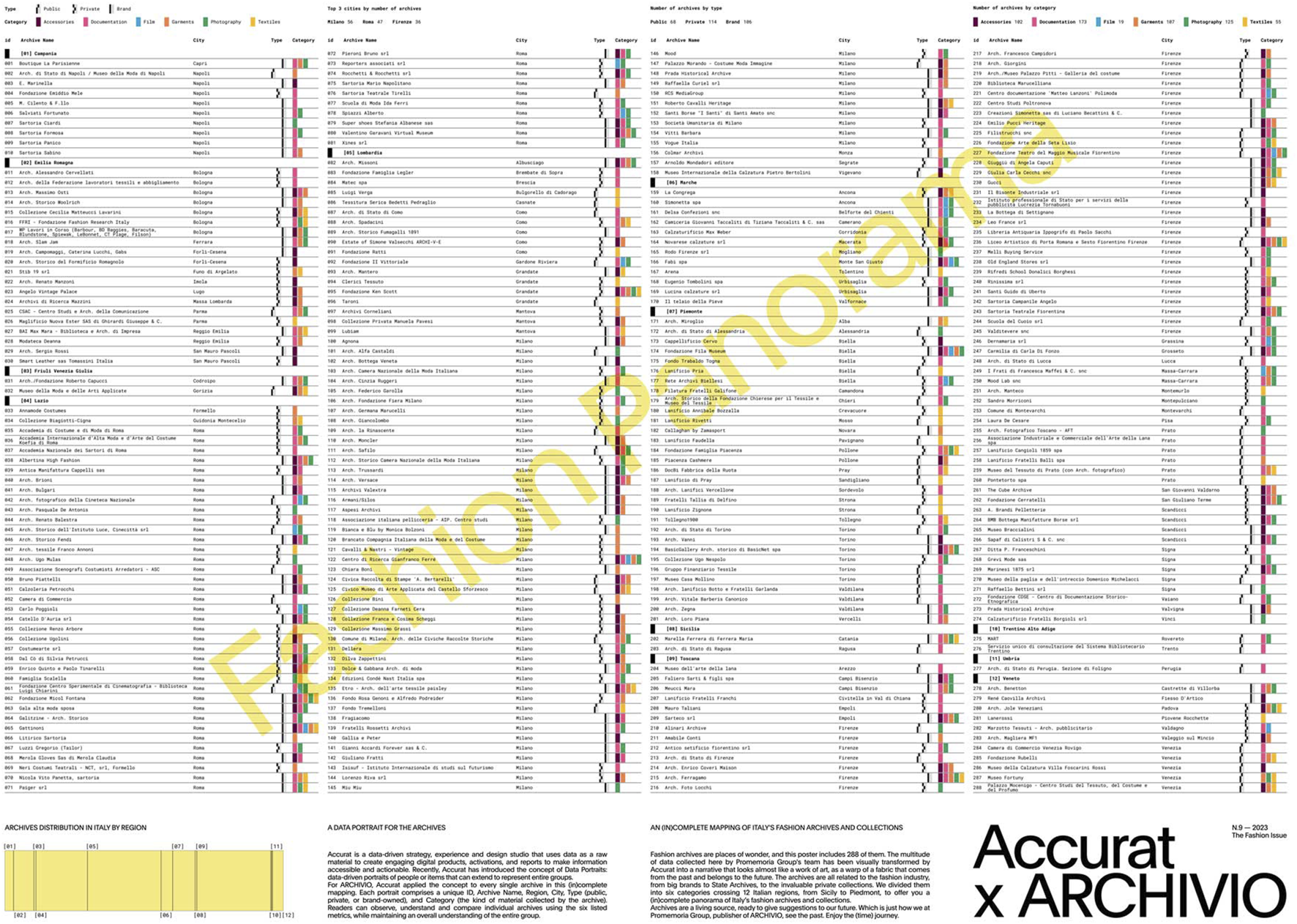

In addition, although the analysis is limited to a single Italian case study, it addresses a pressing gap in national discourse, as stated in the introduction to this paper. An initial call for an urgency in mapping the field of fashion digital archives originally arose from Promemoria itself, with their issue of Archivio Magazine dedicated to fashion archives worldwide. Promemoria, in fact, also takes care of organising cultural initiatives around the field of archives, one of them being Archivio Magazine itself. “The Fashion Issue” featured a series of archival institutions divided into three main categories: public, private and personal ones. Alongside the issue, Promemoria published a national map of fashion archives in each Italian region, providing valuable data on the diffusion and typology of archives in the territory (Figure 1). As underscored in this act, the need to articulate a situated reflection on fashion heritage in Italy is particularly urgent. Promemoria’s work directly addresses this gap: through extensive research and mapping, their collaboration with data design studio Accurat, resulted in a dynamic visualisation of Italy’s archival fashion landscape, further illustrating the breadth and typological diversity of existing repositories, both institutional and independent.

FIGURE 1

Vogue Italia archive (front-end). Query: Vogue Italia Ottobre 1994. Reproduced with permission from Condé Nast, Vogue Archive Italia (https://archivio.vogue.it/).

Results

Since its founding in 2011, Promemoria has been committed to “systematising heritage knowledge” (Promemoria, n.d.). Promemoria’s work spans from the digitisation of historical archives to the creation of archival ecosystems that reflect the past, connect with the present, and envision the future (Promemoria, n.d.). As our interview will demonstrate, Promemoria’s approach, by combining scientific rigour with a creative and narrative-oriented methodology, reveals the archive not as a static container, but as a living site of identity construction and cultural negotiation.

One of Promemoria’s earliest engagements in the fashion field was the digitisation of the Vogue Italia archive – an ambitious project that laid the groundwork for their later methodologies. In our interview, Cecilia Botta explains that Promemoria developed the back-end for a dedicated digital platform (whose front-end was subsequently developed by a different agency) “to make all of Vogue’s content – originally produced for print – searchable online” (Supplementary Appendix), meaning enabling users to browse past issues and retrieve specific articles or editorials using simple keywords, such as “the designer’s name, collection, brand, photographer, model, stylist, and so on” (Supplementary Appendix). Rather than employing a traditional cataloguing approach, Promemoria opted for what they describe as “a true tagging process that enables this kind of digital search” (Supplementary Appendix), allowing the archive to function as “an active resource for research, inspiration, and understanding the evolution of fashion and culture” (Supplementary Appendix). The process is not static: “it’s a tagging process that we carry out regularly on a monthly basis, ensuring that each issue is searchable online” (Supplementary Appendix). Through this continuous effort, the archive is built as its physical counterpart is being published, making it an ever-evolving digitised collection that mimics the original material’s pace and dynamics (Figures 2, 3).

FIGURE 2

Vogue Italia Archive (front-end). Double spread with pages overview. Query: Vogue Italia Ottobre 1994. Reproduced with permission from Condé Nast, Vogue Archive Italia (https://archivio.vogue.it/).

FIGURE 3

Accurat x Archivio, The Fashion Issue. Reproduced with permission from “Data Portraits convey the unique heritage of Italian fashion and design” by ARCHIVIO MAGAZINE (https://studio.accurat.it/).

The challenges of archiving fashion

As stated in the first section of this paper and highlighted from the literature review, archiving fashion presents a set of unique challenges that transcend the typical parameters of archival work, an act that mainly pertains to documents outside the field of fashion or design in general. It has been demonstrated in previous paragraphs that fashion archives must grapple with a complex layering of materiality, a complex dynamic that intrinsically involves ephemerality, and a strong visual component that is proper and personal to each archive. This is mirrored in the Vogue archive, becoming the first official challenge that Promemoria had to face in the field, grappling, from the very beginning, with a strong visual identity – from the Sixties onwards – and a periodical nature. As Cecilia Botta highlighted, “the challenge is starting from the visual impact that the final result should have, because the output must align with the collections that are being archived. It’s necessary to think about how the archive will be used” (Supplementary Appendix). In this sense, the visual language of fashion must be reflected in how digital archives are structured and accessed, a feature that was reflected in the choices first made for the Vogue Italia archive, to be able to flip pages a to see the publication in double spreads, just like you would for the physical copy (Image 1). As such, Promemoria believes that “navigation strategies must be as realistic as possible”, with “a logical structure designed to convey the company’s know-how in its specific field” (Supplementary Appendix).

Moreover, a second challenge lies in logistics, especially when dealing with physical garments and objects. “These items often need to be moved,” Botta notes, “so there’s also a logistical component regarding the location and movement of the object, which opens up different technological scenarios and issues that we develop solutions for” (Supplementary Appendix). If digitising a complete run of a fashion monthly magazine is a huge but potentially manageable task in terms of materials to employ (e.g., boxes for moving the issues, professional scanners to detect a page of fixed measure), the practical scenario changes when dealing with an enlarged typology of materials to engage with. The heterogeneous nature of fashion archives poses additional complexity. Botta reiterated what was highlighted in previous sections of this paper, meaning that fashion archives might include several objects ranging from garments and accessories, but also “sketches, catalogues, materials related to photoshoots or advertising campaigns, sample books, trademarks, window display designs, graphics, and various forms of design” (Supplementary Appendix). As she observes, “just from this list of materials, it’s clear how different this is from an archive that mainly contains documents or historical photographs” (Supplementary Appendix).

The interview also echoed certain key distinctions between public and private archival models, and the consequences they entail when approached for digitisation. In the private sector, “the main goal for private companies is to turn their historical archive into a strategic asset, transforming historical heritage into a tool to strengthen brand identity” (Supplementary Appendix). Archives in this context are leveraged to “support marketing with a communication tool, as well as to provide inspiration for new fashion creations” (Supplementary Appendix). This perspective aligns with Colombi and Vacca (2016) notion of the archive as a “living cultural archive” – a speculative and anticipatory platform that extends beyond preservation, becoming a site of experimentation and future-oriented design. For fashion brands, this goes as further as building a strategic infrastructure for both visual identity and intellectual property: “the historical archive is a strategic asset to build and strengthen brand identity, storytelling, and marketing,” and it “gives the legal departments of these large companies the tools to defend their brand image when it’s being copied” (Supplementary Appendix). This allows brands to “create an emotional connection with consumers, foster loyalty, and attract new customers, often with short-term goals” (Supplementary Appendix).

Public and institutional archives, by contrast, are driven by different goals. Their “mission [is] of preserving collective memory”, with archives designed to “support scientific and historical research and [be] conceived more for public use” (Supplementary Appendix). In these contexts, the archive functions as a space for reflection and cultural continuity, “using it as historical testimony for the broader community” (Supplementary Appendix). As Botta notes, “in public and institutional archives, on the other hand, the goal is the safeguarding of collective memory and cultural heritage for future generations” (Supplementary Appendix). These archives operate with “objectives [that] are long-term” and are “accessible for academic, scientific, and historical research, as well as educational purposes to a broad audience” (Supplementary Appendix). In this case, “preservation itself is a primary goal, followed by the need to make the heritage responsibly accessible” (Supplementary Appendix).

Digital production processes: the memories method

Promemoria Group approaches digital fashion archiving with an adaptive methodology, the “Memories” method. When asked about the intention of creating a universal system for digitising fashion archives, Botta explained that their method is rather a way of creating a highly customised approach, driven by the unique requirements of each client and the inherent heterogeneity of fashion archives (Supplementary Appendix). As Cecilia Botta recognises, among the archives they manage, “there are significant differences, often depending on the purpose the archive serves for the client” (Supplementary Appendix). This commitment to customisation ensures that the method, while providing a “consistent modus operandi that ensures quality and depth in the analysis and structuring of an archive,” is nonetheless “tailored – like a bespoke garment – to the specific needs of each brand, enhancing its uniqueness” (Supplementary Appendix). This adaptive strategy fosters an “organic way of working,” where innovations often originate from specific client needs but can then be adapted and applied more broadly, revealing a beneficial “hybridisation” across diverse creative fields like fashion, architecture, art, and design (Supplementary Appendix).

The operationalisation of the Memories method unfolds through a series of distinct phases, beginning with the immediate formation of a dedicated team, specific to each project. This team first engages in an “exploratory phase,” assessing the archive’s existing contents, its structure, and the client’s desired outcomes (Supplementary Appendix). This then leads into a “mapping phase,” involving on-site visits for meticulous counting, recording, and documenting of materials (Supplementary Appendix). Crucially, the third phase focuses on understanding the narrative through “conducting interviews – up to ten per project – with founders or key figures who can recount the company’s or institution’s milestones,” while simultaneously identifying key classification terms to build the foundational vocabulary for the information architecture (Supplementary Appendix). This phase is crucial in framing Promemoria and their method into a more “unofficial” scenario, valuing personal voices and memories to enter, metaphorically, the archive. An “analytical, output-oriented phase” follows, culminating in a comprehensive report that leads into the penultimate phase, involving the “design of the information architecture,” where the team conceptualises the digital platform’s filters, nodes, and categories for effective storytelling depending on the needs and goals of each client, thereby creating the initial logical structure of the platform (Supplementary Appendix). The cumulative result of these meticulously tailored phases is a bespoke digital platform, housing vast collections of items, all intricately designed “to narrate the story of the company or project” (Supplementary Appendix).

When asked about the choice of the name behind the method, Promemoria specified that the term “memory” naturally entails a digitised archive that transcends mere data management, embodying a profound anthropological and humanistic approach to heritage from the very beginning of the name itself (Supplementary Appendix). Rather than viewing the archive as a static collection of objects, materials, and documents, Promemoria understands it as a “living organism – a true repository of knowledge” (Supplementary Appendix). This transformation is achieved by foregrounding “memory and recollection [as] the connective tissue” – hence the series of interviews to begin the analytical phases of their working methodology – that imbues the physical and documentary elements with vitality (Supplementary Appendix).

This method deeply integrates personal stories and oral histories, recognising that these human narratives are what truly generate a company’s “real know-how” (Supplementary Appendix). This emphasis on lived experiences and subjective accounts directly aligns with Laurajane Smith’s (2006) definition of heritage, which posits it as a dynamic cultural and discursive practice rather than an immutable, fixed entity. Without this crucial phase of personal storytelling, Promemoria’s method asserts that the essential “relationships that are central to our method are missing” (Supplementary Appendix). Thus, for Promemoria, systematising memory in the digitised version of an archive also entails actively cultivating a rich, interconnected tapestry of human experience and narrative, ensuring the archive serves as a vibrant, evolving source of insight and understanding.

The role of human labour in technological infrastructures

The digitisation of various fashion archives, as exemplified by Promemoria Group, profoundly involves the often-invisible role of human labour in shaping digital platforms. Far from being a purely automated process, the “Memories” method is underpinned by a diverse array of specialised human roles and an adaptive approach to expertise. Key managerial oversight is provided by figures such as the Chief Operating Officer and Project Manager (Supplementary Appendix), who orchestrate the complex stages of archival development. Crucially, the core “Memories” team, which is put together for every new Promemoria client, integrates “both professionally trained archivists and hybrid profiles”, fostering a strength that lies in a “relational and research-oriented” methodology rather than a purely scientific and archival one (Supplementary Appendix).

This humanistic approach to each project also applies to specific roles dedicated to ensuring data quality: “two people [are] responsible for Data Quality who handle the selection, research, and cataloguing processes” (Supplementary Appendix). The physical transformation of materials into digital assets relies on a “dedicated digitisation team, composed of photographers as well as technicians who operate standard digitisation systems” (Supplementary Appendix). Beyond mere technical execution, human intellectual labour shapes the very structure of the digital output: the “platform’s structure is designed by our Scientific Director, a figure who identifies the best system for narrating what emerged from the interviews,” developing “actual pathways” – thus links, connections, bridges from one document to another – for storytelling (Supplementary Appendix). Finally, the technical implementation, including complex data migrations, falls under the purview of a dedicated “IT department” (Supplementary Appendix). Promemoria’s human capital also demonstrates remarkable adaptability when faced with the aforementioned logistical challenges inherent in fashion archiving, such as the location of materials for projects based in different cities. To overcome these difficulties, Promemoria trains professionals of that area or relocates some resources where the project is held (Supplementary Appendix). In addition, each project calls for different necessities in terms of materials to approach and digitise, which in turn calls for varied digitisation technologies which Promemoria cannot always support with their own methods. In that case, they adapt and “bring in external professionals” to better support the technical implementation needed, acknowledging that their streght doesn’t lie in the most innovative of technologies but rather in their relational and human-centric view of the digital archive (Supplementary Appendix). Therefore, as demonstrated by the resources applied by Promemoria, the multifaceted nature of digitised fashion archives can be essentially considered as the result of professional human intervention, as seen by the complex layering of human skills across management, archival, technical, and artistic realms.

Between communication, secrecy and memory

Beyond the technical and labour-intensive aspects of digital archive systematisation, Promemoria Group actively engages with the strategic challenges and opportunities of communicating cultural heritage. While it’s uncommon for a company focused on the technicalities of archive building to invest in cultural communication, Promemoria has cultivated this facet through two distinctive special projects. The first is Archivissima, a nationwide festival dedicated to archives, and the second one is the aforementioned Archivio Magazine (Supplementary Appendix). Both initiatives serve as vital tools for Promemoria to gain visibility and for participating businesses to display a section of their archives, providing controlled access to their heritage, thus partially bridging the secrecy behind private archival materials (Supplementary Appendix).

These initiatives are once again evidence of how the communication of private and physical fashion archives that are being digitised challenges the balance between public engagement and the imperative of secrecy. In sharp contrast to institutional and cultural archives, which are typically more widely available, the majority of Promemoria’s brand archives are still private and closed, even though digitised (Supplementary Appendix). Nicoletta Esposito confirms that fashion, in particular, demands greater control from a communication standpoint, as brands often seek to avoid “disclosing their private and distinctive know-how”, which serves as their main asset and strength (Supplementary Appendix). For Promemoria, this translates into a confidentiality agreement for nearly all client-specific development, meaning they “can’t fully disclose everything that has been done – unless it results in one of these special editorial or exhibition projects”. Therefore, they are unable to completely disclose and express what they do, even if sharing their approach to each archive would constitute their most effective communicational aspect (Supplementary Appendix).

To address this delicate balance, Promemoria proposes projects that extend “beyond the archives” themselves, acting as support teams for either client’s curator to suggest relevant materials from their catalogued “memorabilia,” based on what they have researched and gathered, or even taking on the curation of content for specific projects themselves (Supplementary Appendix). This highlights the intricate interplay between archival preservation and its communicative and narrative functions, which Promemoria views as “two sides of the same coin” (Supplementary Appendix). The firm believes that “preservation and communication constantly interact,” asserting that communicating “encourages investments and approaches aimed at both preserving and enhancing the archive itself” (Supplementary Appendix). Conversely, Promemoria believes that a “preservation that is ‘immobile’ inevitably leads to forgetfulness and loss of value” (Supplementary Appendix), a concept that lies in ideological balance with an idea of feasible future for the archive.

Looking ahead, in fact, Promemoria Group envisions a transformative future for digitised archives, moving beyond their attributed function of passive repositories to become dynamic, interactive “laboratories” of ideas. In this vision, Promemoria hopes to redefine user engagement, shifting from simple “consultation” to much more immersive, personalised, and creative interactions (Supplementary Appendix). This vision was already present in Promemoria’s view from the very first fashion project, the Vogue Italia archive, where users or visitors can save and pin their research in a section called “Portfolio”, and decide whether to make it publicly accessible, thus to share their research pathways (Figure 4). In this evolving landscape, the digital archive isn’t just a backwards-looking historical record; it becomes a vibrant hub connecting a brand or institution’s past, present, and future.

FIGURE 4

Vogue Italia Archive (front-end). Portfolio section.

This vision includes scenarios where external users, like visitors, could actively contribute their memorabilia, thus fostering a participatory environment in the archive (Supplementary Appendix). Such enhanced interactivity transforms the archive from a mere “information repository into a true ‘laboratory’ of ideas, a continuous source of inspiration, and a strategic tool” for innovation and brand development (Supplementary Appendix). By facilitating these fluid exchanges and dynamic engagements, Promemoria Group aims to unlock new value from archival content, making it an active, evolving component of cultural and commercial strategy.

Discussion

This paper has explored the hidden process behind the systematisation of digital fashion archives, drawing on the unexplored case study of Promemoria Group. By distinguishing between the different typologies of fashion archives in the digital realm and drawing a comprehensive background in the past literature, both in the Italian and international archival scenario, we have highlighted the inherent complexities and challenges associated with materialising, preserving, and curating archival fashion in the digital age.

The increasing involvement of private companies in the digitisation of their own fashion archives raises important questions about ownership, responsibility, and access. While these projects can safeguard fragile materials and transform them into strategic assets, they often remain closed to the public, accessible only to internal teams or showcase a curated selection of the totality of their collection, thus shaping an image of heritage that is filtered before reaching the public. This restricted accessibility underscores a fundamental tension between private interests and public responsibility. Furthermore, such a private control of these archives suscitates a consequent reflection on the perdurance of these histories and the potential dispersion in case of lack of private investment.

Moreover, our interview with Cecilia Botta and Nicoletta Esposito, and the subsequent analysis of Promemoria’s “Memories” method, while addressing this specific issue, also revealed a highly adaptive and human-centric approach to digitising fashion. Far from a standardised technical solution, this methodology is tailored to the unique specificities of each client, emphasising an anthropological and humanistic perspective that prioritises storytelling, oral histories, and memory over mere data collection.

Furthermore, the study illuminated the critical interplay between human labour and technological infrastructures. We demonstrated how a diverse and tailor-made ecosystem of skilled professionals collectively underpins the construction, accessibility, and perception of digitised fashion heritage. This extensive human input, often “invisible” to the end-user, is indispensable in navigating the complexities of content production, information architecture, and the logistical challenges inherent in fashion archiving.

Therefore, this paper contributes to situating the analysis of fashion archives within a fashion studies lens, enabling us to interrogate not only the contents of archives but also the technical processes, power dynamics, and labour relations involved in their making. Moving beyond an object-oriented or merely technological approach, it becomes possible to write a history of archives as cultural and political constructs, examining how decisions about what to preserve, how to classify it, and who can access it are shaped by hierarchies of expertise, institutional control, and corporate strategy. Such an approach foregrounds the production of the archive itself as a site of meaning-making, rather than a neutral “container” of the past.

Finally, our interview also shed light on Promemoria’s communication strategies, underscoring the delicate balance between promoting cultural heritage and maintaining brand secrecy. This tension between preservation and public dissemination, however, is not a dichotomy but, as Promemoria posits, two sides of the same coin: active communication is crucial for justifying investment and ensuring the long-term vitality of digital archives, transforming them from static repositories into dynamic “laboratories” of ideas and inspiration.

In conclusion, the Promemoria Group case study offers a valuable lens through which to understand that the practices of digitising fashion collections are not merely technical endeavours, but appear as complex networks where human expertise, strategic subjectivity, and thorough communication converge to redefine the construction of fashion’s past for accessibility in future purposes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because Interviewees were selected based on their direct involvement in the case study and voluntarily agreed to participate in the interviews. All participants received clear information about the purpose of the study, the intended use of the data, and the procedures for data storage. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the interviews. In this study, interviewees are identified by name. This was explicitly communicated to participants, and explicit, informed consent was obtained for the public use of their names and statements. The researchers acknowledge the increased ethical responsibility that comes with the inclusion of identifiable human data and have taken care to ensure participants’ understanding and agreement. The interview transcripts will be made publicly available with the publication of this paper. Formal ethics approval was not required for this study, as participants voluntarily took part with the intention of contributing their professional perspectives on their workplace and methods (the paper’s case study). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ejcmp.2025.15268/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^Italian for “Unified Information System for Archival Superintendencies”.

2.^Italian for “General Directorate for Archives”, an arm of the Italian Ministry of Culture.

3.^Italian for “Italian National Archival Association”.

4.^Italian for “Portal of the Fashion Archives of the XX Century”.

5.^Italian for “National Archival System”.

References

1

BondielliD. (2001). SIUSA: Genesi e sviluppi di un progetto. Bollettino d’informazioni. Centro di Ricerche Informatiche per i Beni Culturali, Scuola Normale Superiore. Pisa. Available online at: https://siusa-archivi.cultura.gov.it/documenti/SIUSA_Genesi_e_sviluppi_di_un_progetto.pdf.

2

CalancaD. (2020). Archivi digitali della moda e patrimonio culturale tra descrizione e integrazione. ZoneModa J.10 (2), 11–25. 10.6092/ISSN.2611-0563/11793

3

ColombiC.VaccaF. (2016). The present future in fashion design: the archive as a tool for anticipation. ZoneModa J.6, 38–46.

4

FoucaultM.MiskowiecJ. (1986). Of other spaces. Diacritics16 (1), 22–27. 10.2307/464648

5

FranceschiniM. (2019). Navigating fashion: on the role of digital fashion archives in the preservation, classification and dissemination of fashion heritage. Crit. Stud. Fash. and Beauty10 (1), 69–90. 10.1386/csfb.10.1.69_1

6

GilmanS. L.DeleuzeG.GuattariF.MassumiB. (1989). QA thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. J. Interdiscip. Hist.19 (4), 657. 10.2307/203963

7

HewisonR. (1987). The Heritage Industry. Britain in a Climate of Decline. London: Methuen.

8

HuntC. (2014). Worn clothes and textiles as archives of memory. Crit. Stud. Fash. and Beauty5 (2), 207–232. 10.1386/csfb.5.2.207_1

9

LehmannU. (2018). Fashion and Materialism. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press, 35–68. 10.1515/9781474407922-004

10

ManoffM. (2006). The materiality of digital collections: theoretical and historical perspectives. Portal Libr. Acad.6 (3), 311–325. 10.1353/pla.2006.0042

11

MartinM.VaccaF. (2018). Heritage narratives in the digital era: how digital technologies have improved approaches and tools for fashion know-how, traditions, and memories. Res. J. Text. Appar.22 (4), 335–351. 10.1108/RJTA-02-2018-0015

12

Ministero della Cultura (2025). Portale degli Archivi della Moda del Novecento. Available online at: https://archivi.cultura.gov.it/strumenti-di-ricerca-online/il-sistema-archivistico-nazionale-san/i-portali-tematici/portale-degli-archivi-della-moda-del-novecento (Accessed May 16, 2025).

13

MontorioA. (2021). Promemoria. Come creare l’archivio dei propri ricordi. Torino: ADD Editore.

14

PecorariM. (2019). Fashion archives, museums and collections in the age of the digital. Crit. Stud. Fash. and Beauty10 (1), 3–29. 10.1386/csfb.10.1.3_7

15

Peirson-SmithA.SmithP. (2021). Fashion archive fervour: the critical role of fashion archives in preserving, curating, and narrating fashion. Archives Rec.41 (3), 274–298. 10.1080/23257962.2020.1813556

16

PetersL. D. (2019). A history of fashion without fashion: recovering the stout body in the digital archive. Crit. Stud. Fash. and Beauty10 (1), 91–112. 10.1386/csfb.10.1.91_1

17

Promemoria Group (n.d.). About. Promemoria Group. Available online at: https://www.promemoriagroup.com/it/about/.

18

RocamoraA. (2012). Hypertextuality and remediation in the fashion media: the case of fashion blogs. Journal. Pract.6 (1), 92–106. 10.1080/17512786.2011.622914

19

SmithL. (2006). Uses of Heritage. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Routledge.

20

SulsD. (2017). Europeana Fashion: past, present and future. Art Libr. J.42 (3), 123–129. 10.1017/alj.2017.18

21

TrameI. (2023). Fashion libraries: between material and immaterial shelves. Fash. Highlight1 (1), 128–135. 10.36253/fh-2270

22

VaccaF. (2025). Living cultural heritage: exploring fashion heritage within corporate archives. ZoneModa J.14 (2), 1–17. 10.6092/ISSN.2611-0563/20700

23

VandiA. (2023). Dealing with objects, dealing with data. The role of the archive in curating and disseminating fashion culture through digital technologies. ZoneModa J.13 (1S), 155–168. 10.6092/ISSN.2611-0563/17935

Summary

Keywords

digital archives, digital labour, fashion archives, heritage, interface design

Citation

Trame I and Pecorari M (2026) Digitising fashion archives: methodologies, labour and interfaces through the case of promemoria group. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 15:15268. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2025.15268

Received

14 July 2025

Revised

12 November 2025

Accepted

30 December 2025

Published

18 February 2026

Volume

15 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Trame and Pecorari.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ilaria Trame, ilaria.trame@polimi.it

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.