Abstract

This research investigates the intersection between curatorial practices and technological mediation in fashion exhibition design, and looks into how technological integration can build upon curatorial approaches. Technology has received significant attention concerning its integration within exhibition contexts; however, its mediation role in reshaping fashion curatorial processes remains uncodified. This study attempts to articulate an approach to augmenting curatorial practices through technology to deeper engage with and understand the multilayered narratives embedded within fashion artifacts. Drawing from cultural theory, the research positions curation as a critical practice of representation that bridges heritage and contemporary discourse. It explores how curatorial decisions–object selection, narrative construction, spatial arrangement, and visitor engagement–frame cultural storytelling mechanisms. Through design research–combining literature reviews with participatory observation–the article proposes a possible useful (non-exhaustive) codification of fashion curation, by proposing an interpretive framework comprising three interrelated models: Narrative (content and themes), Staging (spatial and visual storytelling), and Experience (audience interaction and mediation). The article describes then how the framework was used and tested through collaborative workshops between the authors and their reflexive analysis specifically focused on two case studies, specifically chosen to highlight the overlapping cresearch interests of the authors: Cristóbal Balenciaga: Fashion and Heritage “Conversations,” with a focus on object-centered curation within one archive, and Homo Faber: Fashion Inside and Out, with the brief to draw attention to fashion craftsmanship processes. Both exhibitions were curated and designed by Clark and had previously been analyzed by Vandi, who participated as an external observer. Since the exhibitions examined in the workshops did not include digital elements, the results of the workshops provided a basis for discussing how technologies, when purposefully integrated, can amplify the curatorial intent, the spatial narrative and enrich the cultural experience of visitors. Findings reveal how digital tools can serve not as add-ons but as integral components of the curatorial process, extending the power of “props” –intended as “exhibition prosthetics” used to mediate, complicate, and contextualize the objects on display–and narratives from behind-the-scenes decisions to public-facing engagement. The research introduces a conceptual and practical model for fashion curators, proposing a shift from technology as spectacle toward technology as strategic narrative enhancer. Implications may redefine the future design of exhibitions, informing both the practice of curation and the visitor experience in a more codified, interpretive, and technologically supported manner.

Introduction

There has been a seismic shift in the role and reputation of curatorial practices around fashion and its archives over the past 50 years, with an exponential rise in the sheer number of projects that define themselves as such since the 1990s and 2000s. Whilst a very broad brush account of the evolving field included early descriptions of its suffering due to poorly funded and poorly credited museum departments, now the discipline is being instead criticized for its successes. The debate seems to assume there is a “correct” amount of visibility of dress - not too little (it is one of our most efficient social and cultural barometers) and not too much (or it smacks of commercialism and loss of a critical voice).

It is as though we need to think about concentration and relevance: what American scholar Elisa Tamarkin reminds us in her wonderful book Apropos of Something: A History of Irrelevance and Relevance (Tamarkin, 2022); as sitting somewhere within the categories of attention and importance. The museum tells us why an object is worth looking at (and that it is worth looking at simply by virtue of being there) as a sequence, as a chorus, as distinct, as representative and so on, and exhibition-making modes help to make that knowledge memorable. As framed, paced, theses, exhibitions often cover vast histories told through a relatively small series of carefully selected objects, carefully conserved, carefully lit to conservation levels, carefully managing and manipulating our attention.

We are told visitors no longer have the concentration, nor the patience, for museums to rely on the objects alone: we are not to rely solely on close reading. But whilst it is the drama of the introduction of new digital modes of engagement that has often taken centre stage, there is another aspect of its uses, that has been perhaps less articulated, one which works on the side of multiplying or augmenting the cultural layering of the object, the multiple perspectives of which the curator has until now been allowed to privilege only one.

The workshops that this paper documents and what Angelica Vandi’s careful doctoral research hopes will emerge is which aspects of current curatorial practice need protecting and which aspects of the curatorial process (and the process of making not only the objects on display but the exhibition itself) can be better explained with a different, new, set of tools harnessing technologies’ capacity to extend beyond the material present.

Different models of travel through an exhibition are now available - not only via the extended story, but we can wonder what relationship may be established with the unpredictable, the immeasurable, the detour, lingering, or even the subtle as the American writer and activist Rebecca Solnit’s books would have our narrative journeys become. These categories might come into play as well, as history has taught us of the perils of the too-confident frame. We now hopefully can take for granted that there is not a single storyline and where there is one, it is often on the side of oppression and cultural colonisation. So how do we “immerse” our visitors in an exhibition without drowning out their essential and useful resistances. Our conversations wanted to open up more thoughts and not shut them down in the name of immersion, but instead think of immersion as a new way of talking about exhibition-making.

The kind of work that I have been working on for 30 years and the reason for Vandi’s request to begin our dialogue was due to my work at the borders of objects on display, investigating (albeit often materially and not digitally) the idea of the exhibition as a rhetorical device, and that the introduction of new objects (effects, props, models), might be a way to formulate and articulate exhibition research away from the central object/caption dyad, and instead activate different forms of spatial and textual resonance. These considerations felt as though they may contribute to the ways in which digital layering and augmentation might come in, extending the possibilities for exhibition-making practices’ nuance.

The two exhibitions that we chose together and are studied here were chosen for their different approaches, both in terms of emphasis and curatorial mandate as case studies for the authors’ overlapping concerns. They were chosen as starting points for the participatory observation, and differentiated in terms of both object selections and representation purposes and objectives:

• Cristóbal Balenciaga. Fashion and Heritage “Conversations” was held from March 2018 to January 2019 at Balenciaga Museoa in Getaria. The exhibition was created from the museum’s existing Balenciaga archive and was organised around creating a progressive, chronological dialogue between the objects displayed. The focus was on performing the canon of Cristobal Balenciaga’s work built up throughout his career through the garments, adding visual interpretive layers (photography, research, curation and museography) that have built upon his heritage/legacy more recently to reinforce that canon.

• Homo Faber. Fashion Inside and Out, was held from September 14th to 30th, 2018 and set within the broader initiative “Homo Faber” by the Michelangelo Foundation for Creativity and Craftsmanship at Fondazione Giorgio Cini in Venice. The focus was on staging the craftmanship within fashion, and making the processes of meticulous work visible. Unlike the exhibition at Balenciaga Museoa, this exhibition started from a selection of objects from multiple archival sources that spanned the last 20 years of fashion’s avant-garde, bringing together works by fashion designers that placedtheir collaborative approach under the spotlight in order to represent [tacit] knowledge inherent to crafts techniques, in this case in the transformation of natural and raw materials, and surface decoration.

Materials and methods

Before presenting the practice-based activities that form the focus of this article, a critical review of curation fundamentals, fashion curation, and exhibition design was undertaken in the context of Angelica Vandi’s PhD research titled “Archiving Fashion Futures: Design-driven Curatorial Practices Fostering Innovation in CCIs” (Vandi, 2024) examined in June 2024 that focused on understanding how technologies could intervene in amplifying and representing the inherent knowledge preserved inside fashion heritage artefacts. The literature review was required to adopt a critical perspective on the theories, methods, and professional practices that have shaped curation as a core cultural practice for the representation and understanding of the various levels of implicit knowledge belonging to fashion’s cultural heritage, as seen through the lens of exhibitions. Concurrently, it aimed to investigate the primary design phases inherent to curation, essential for the realisation of an exhibition.

This initial phase laid the foundation for an experimental research practice, which remains part of the PhD research experiments, shaped by the authors and aimed at ultimately understanding the potential of digital technologies to redefine existing curatorial practices through innovative curatorial models.

This article presents one of the practice-based workshops conducted as part of a broader series of participatory and interview-based activities developed throughout Vandi’s doctoral research. These activities engaged key curators operating across the wider fields of fashion and design, intending to investigate curatorial approaches to fashion heritage. The specific workshop discussed here represents a significant component of the research findings and was carried out in collaboration with the article’s co-author, Judith Clark. Its primary objective was the conceptualisation and codification of Clark’s curatorial methodologies, particularly those employed in the curation and representation of fashion heritage.

Following this outline, Participatory Observation (PO) was chosen as a preferred method for its inherently qualitative, interactive, and relatively unstructured nature. Moreover, “it is generally associated with exploratory and explanatory research objectives–why questions, causal explanations, and uncovering the cognitive elements, rules, and norms underlying observable behaviours. The data generated are often free-flowing and the analysis much more interpretive than in direct observation” (Jorgensen, 2011)

Indeed, within the article’s context, PO facilitated the collection of qualitative data regarding understanding mechanisms and rationales of curatorial dynamics by relating Angelica Vandi to selected contextual and practice-based experiences developed by Judith Clark. Indeed, the different profiles of the authors were complementary in this experience:

Angelica Vandi is a fashion design researcher at the Design Department at Politecnico di Milano, focusing on experimenting with new experiential and design models to represent and narrate tangible and intangible cultural heritage preserved in archives and belonging to the Cultural and Creative Industries (CCIs) for further use in research, education and dissemination contexts.

Judith Clark is among the most renowned practitioners and academics in fashion curation, having contributed substantially to the definition and consolidation of the discipline over the past two decades. Since founding the Judith Clark Costume Gallery in London in 1997, she has pioneered innovative ideas and approaches to represent fashion heritage. She has overseen more than 50 fashion exhibitions at major museums and, as former director of the MA in Fashion Curation and professor of Fashion and Museology at the London College of Fashion [UAL], she is decoding her approach to pass it on and teach it to future generations of professionals.

The evidence generated by her work made her a prime example of best practice for the research to engage with, to seek validation for the codification of an augmented curatorial practice. In particular for:

• The thorough engagement with close examination of the archive. Clark’s practice often starts with the study of the archive and develops in specific stages. This method emphasises a dedicated commitment to viewing exhibitions as complete projects that find their genesis within culturally relevant objects and evolve in predetermined ways based on the stories that flow from the analysis of these. An essential aspect is to avoid the isolation of clothes from their environment, always focusing on the exploration and representation of their context, to materially represent the intangible aspects of the research, suggested through new collaborative practice, that allow for a holistic understanding of the object within the exhibition. It is important to note here that the history of the exhibitions associated with the archival objects (the ways in which they have been exhibited in the past) is also always sistematically close read by Clark. Ref. 28 Aspects chapter in Exhibiting Fashion: Before and After 1971, reveals her method of close reading exhibition history (Judith Clark and Amy de la Haye, 2014).

• The relevance given to the physical space and scenography. Rooted in her academic background in architecture - an aspect that underpins her primary identity as an exhibition maker rather than solely a curator - the translation of inspiration and narrative derived from the archival context is explicitly intertwined with the spatial configuration of the dedicated exhibition environment. Drawing on an architectural sensibility mindset, she always adopts a holistic approach to the design of space. This meticulous attention to space allows viewers to approach the archive in different ways, moving beyond the concept of the object per se and leveraging on the medium of installations and other spatial possibilities to recontextualise the artefacts within the exhibition.

• The collaborative nature of exhibition design. Clark consistently employs a collaborative team in her curatorial practice. Dialogues between practitioners, partnerships, and commissioned contributions are essential to create a cohesive exhibition project. Collaborations with creatives, including designers such as Hussein Chalayan, Stephen Jones and Naomi Filmer, architects such as Yuri Avvakumov and illustrators such as Ruben Toledo, exemplify her international network. Her perspective emphasises the importance of exhibitions that are not confined to closed, didactic systems. Through these external collaborations, Clark seeks to incorporate viewpoints that fall outside and add to the more traditional chronological and historical narrative of the archive. This is achieved through multidisciplinary approaches derived from the breadth of expertise of the team formed, and introduces a sense of aesthetic and experiential diversity to the exhibition.

As anticipated, the participatory observation method was structured and applied through a set of one-to-one “Knowledge-sharing workshops” between the authors with specific objectives in mind:

• Consolidating the core principles of curation: The primary goal was to delve into some foundational principles of curation. This involved an in-depth preliminary exploration of its distinct approaches and attitudes concerning the construction and communication of narratives through the impactful medium of exhibitions. During the actual participatory observation activity, the curator and the researcher engaged in discussions, broader case studies, and practical exercises to grasp the essence of the curator’s practice.

• Exploring the evolutionary phases of existing curatorial processes: Another key focus was the researcher’s familiarisation with the evolutionary steps constituting the traditional curatorial process. Workshops provided comprehensive insights into the sequential development of this process, emphasising the critical elements of decision-making at each phase, regarding fashion exhibition-making within musems.

• Crafting a foundational analytic framework: A pre-designed foundational framework–created by Vandi based on literature review, desk research and interviews carried out during the PhD research–acted as a major asset of the workshops. The framework was a baseline for participatory observation of existing curated fashion exhibitions and a flexible and adaptive tool whose validity needed to be verified through the activity. Furthermore, meetings were held to check if integrating technological agencies – spanning from XR to the generative AI technologies–could update and “augment” the framework. Ultimately, the goal was to synthesise the framework as one of the critical outputs of the thesis work, connecting theory to practice in the field of curatorial practices.

• Keeping reflexivity as a methodological stance: Throughout the workshops, reflexivity was actively maintained as a methodological standpoint. Both researchers critically examined their positionalities, biases, and decision-making processes. Reflexive and iterative discussion sessions were adopted to uncover assumptions and surpass the interpretive quality of the observational data. This reflexive and dialogic approach is evident in the way the workshop results are presented in Section Results.

Results

The knowledge representation framework in curatorial practices

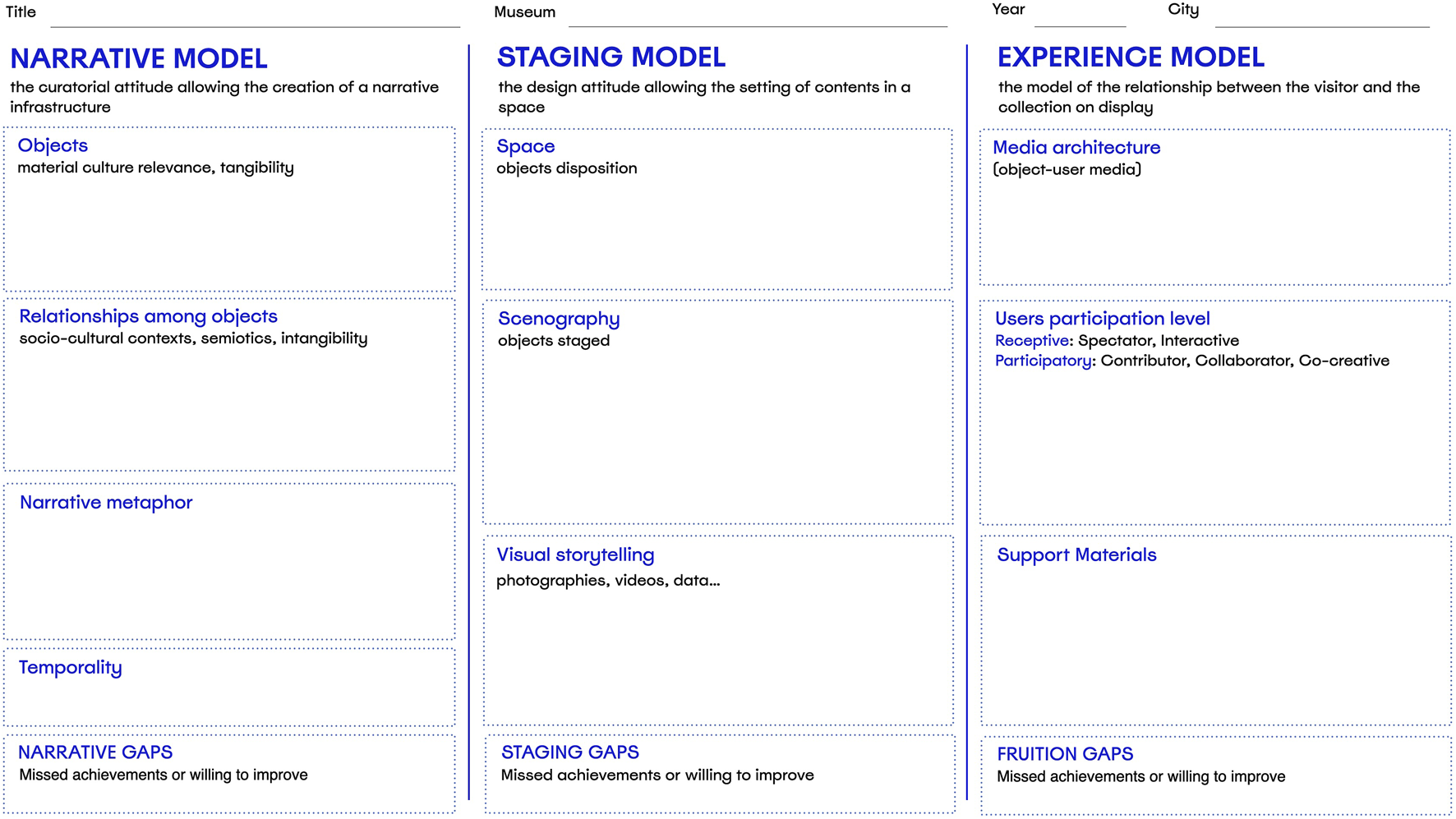

As anticipated, a pre-conceived framework named the “Knowledge Representation Framework” was the starting point for the participatory observation of already selected exhibitions curated by Clark, as well as a flexible tool whose validity had to be tested throughout the activity. The framework was structured according to three central clusters that constitute the main phases of any curatorial process (

Marchetti, 2016;

Vänskä and Clark, 2017;

Trocchianesi, 2022) for an exhibition and branched out into subsections aimed at contextualising and assessing the practice in detail. In particular:

• The narrative model delves analytically into the intrinsic scaffolding of the exhibition’s storytelling approach, investigating the “behind the scenes” of the overall narrative ideation process. This is the most research-intensive stage because it involves a profound and extensive exploration of narrative possibilities that need to be responsive to the exhibition’s theme or storyline in terms of (i) selection of objects, the phase in which curators undertake scholarly research, digging into archives, historical documents, collections, and other relevant sources to scrutinise a multitude of artefacts, ephemera or artworks and evaluating their cultural, historical, or artistic significance. The selection process is often guided by clients’ requests or a priori considerations based on the ability of objects to convey cultural value and preserve their physical condition without being damaged by atmospheric exposure, as well as considerations regarding copyright and brand restrictions. This aspect leads to the second narrative category, which is (ii) the relationships among the objects that represent the specific criteria or standards formulated by curators, guiding the overall selection. Reflections such as the historical-geographical contexts and semiotic references that artefacts embody, as well as their artistic or thematic relevance, may be included in these criteria. This process supports the coherence and alignment with the exhibition’s objectives and feeds into (iii) the narrative metaphor, conceived as the “storytelling” thematic filter which dictates how the exhibition is curated and communicated to the visitor. Relevant is also (iv) the temporality adopted to narrate the objects, whether diachronic, synchronic, or anachronistic (Evans and Vaccari, 2019). Exhibitions often incorporate a chronological or historical timeline to present concepts, but they can also opt for multi-layered temporal approaches to provide depth to the narrative. This could involve temporal discontinuities that allow for the placement of objects of different historical periods side by side to contrast or compare the similarities. This temporal perspective is typical of the exhibited narrative and always triggers critical reflections on how the past configures our current understandings and roots future trajectories.

• The staging model refers to the curatorial design related to the arrangement of the exhibition space, considered as a tool that guides and regulates the exhibition project to effectively translate and communicate the narrative through the display of content. In this context, specific analytical categories may concern (i) the specific disposition of objects in space, being a room in a museum, an art gallery, a pop-up exhibition space, or even a retail store. The space can be temporarily altered by architectural procedures to reflect the brands, design houses, design archives and/or curatorial commissionsinvolving the narrative model, especially when it comes to representing objects’ relationships, considering visual factors like colour schemes, spatial configurations, lighting design, and thematic zoning within the exhibition area. Another category regards (ii) the scenography conceived as display systems built to communicate a predefined idea and increase the narrative efficacy. This term is closely associated with theatre performance techniques as it focuses on how the physical environment, such as mannequins, platforms, lighting and other elements, is designed and used to increase the impact of the narrative and immerse visitors in the exhibition experience. Scenographic choices follow the stylistic approach of the curator and client, which could range from being minimalistic – focusing on simplicity and clean design, with minimal props, subdued colours, and uncluttered spaces to highlight the object qua object–to the use of immersive installations to recreate specific historical settings, natural landscapes, artificial references to specific cultural contexts, and so on. The third subcategory was identified to describe (iii) the visual storytelling, that is, the way other visual media are used to support the object-driven narrative. This aspect involves using images, videos, graphics, or editorial content to complement and enrich the storytelling initiated by the exhibited objects. These visual elements serve as supplementary tools to reinforce the narrative, providing additional context, information, or emotional impact to the exhibition’s themes. The visual storytelling not only supports the object-driven narrative but can also create connections beyond the exhibits, including links and references to broader contexts, such as historical events, cultural references, or societal impacts, thus enriching visitors’ understanding and engagement beyond the exhibits.

• The experience model concerns the curatorial choices related to the experience that the narrative and its staging offer the visitor. It aims to create different levels of engagement, fostering meaningful interactions and experiences for the audience within the exhibition space. It involves designing (i) the media architecture and related contextual touchpoints through the exhibition, where visitors are called to a certain level of interactivity to discover additional context, information, or interactive experiences. These touchpoints involve the integration of interactive tools that mediate the narrative power of the exhibition through the user’s willingness to learn about it. In particular, this refers to information panels, audio-visual installations, QR codes for digital content, or interactive stations strategically placed in the exhibition space to provide additional materials related to the exhibits and strategically engage visitors. Another analytical dimension regards (ii) the level of user participation in the exhibition project, spanning from receptive – where visitors passively receive information presented in the exhibition without active involvement beyond observation (Trocchianesi, 2022; Lupo et al., 2023) – to participatory which includes interactive elements that encourage visitors to actively engage with the exhibition content with the support of types of media architecture installed along the exhibition path. The categories conclude with (iii) extra resources included in the exhibition project, (traditionally) meaning additional materials provided beyond the main content of the exhibition. These can be supplementary texts, brochures, online resources or related publications that offer insights or further information on the exhibits. In this context, an important position is occupied by the exhibition catalogue. Catalogues serve as necessary documentation of the exhibited artworks, artefacts or themes. They capture and provide valuable educational content, including essays, articles, or scholarly contributions from experts in the field, which offer further in-depth analysis and interpretation related to the themes or works in the exhibition, contributing to the scholarly discourse within culturally intensive domains. This content enriches visitors’ understanding and appreciation even beyond the duration of the exhibition: catalogues offer a lasting resource for extended engagement and understanding of the richness of the cultural heritage of which, necessarily, only a part has been exhibited. Additional resources could also be considered a schedule of events related to the exhibition. These events range from workshops, seminars, performances, or guided tours, always acting as enrichment layers, offering additional perspectives, discussions, or experiences that complement the cultural significance of the exhibition.

The framework was arranged as in Figure 1, leaving blank spaces for the compilation of each facet based on the exhibition we wanted to analyse and eventually highlighting the gaps for each of the models.

FIGURE 1

The knowledge-representation framework.

Application of the knowledge representation framework in the workshops

The structure of the workshops followed a two-phase agenda. In the initial phase, an analytical presentation of the selected exhibition was delivered following the defined Knowledge Representation Framework. This was followed by a contextual elaboration that situated the exhibition within its broader conceptual and operational landscape, offering insight into its underlying relationships and intentions. The following paragraphs deliberately retain the dialogic format of the exchange between the two contributors. This approach proves to be consistent with the methodological principle that, being a practice-based discipline, curation cannot be fully understood by isolated reflection or interviews with individual practitioners. Instead, dialogic involvement allows for the expression and documentation of curatorial thinking, capturing the complex decision-making and embodied knowledge that arise during collaborative exhibition-making.

Cristóbal balenciaga: fashion and heritage “conversations”

After Vandi’s analytical presentation of the exhibition following the framework, Clark started by addressing the narrative model contextualising her relationship with the Balenciaga Museum in Getaria, delving into its organisational structure and the professionals involved. In Getaria, the museum houses the historical Balenciaga archive, which connects artefacts with the initial activity of the founding designer himself, while in Paris, the fashion house runs it’s own archive. In her curatorial task, Clark worked alongside Igor Uria, the museum’s curator, a remarkable expert and scholar. The curatorial process began with the Uria’s selection of key silhouettes, while maintaining an active dialogue with the external curator to cut down and regroup the selection of objects. The Getaria museum is an example of how cultural institutions are re-thinking their practices themselves, no longer granitic organs, symbolising a single authority, but systems open to the plurality of voices and testimonies to be discovered within their collections. Indeed, the institution expressed an openness to curatorial subjectivity, positioning individual perspectives and authorial voices as integral to the project. While the staff were already engaged in contemporary analysis of the collection, the curatorial framework allowed for an autonomous approach to the archival records. The intended outcome was to document a distinct curatorial perspective, in line with the institution’s broader commitment to nurturing dialogues around the collection within curatorial practice. This aspect worked against the rehearsed view of a curator’s role bowing to a defended narrative around a brand history. In recent years this apparent lack of independence have been often criticised by academia for conforming too closely to marketing value to the detriment of research. In fact, the Balenciaga Museum has promoted a philosophy in which it does not claim to be the expert, but rather to gather as much knowledge as possible, actively giving value to and seeking external voices and perspectives, placing a great emphasis on the curatorial representation of the complexity and multiplicity of its archive.

“And so, I realised that the essence of this project lay in the conversation. It was truly at its core. That’s why it had to serve as a guiding metaphor within the show, as I relied on their expertise, and I wanted it to be evident that in exhibitions like this, we stand on the shoulders of numerous colleagues. We’re all interconnected, supporting each other; there's no isolated expertise. It pushed me to build things in the space that otherwise might have been a small citation on a caption, such as Olivier Saillard’s exhibition Balenciaga Working in Black that had been staged at the Musee Bourdelle became the caption, built in miniature form and so on…”

The conversation became a way to perform Clark’s own discipline, not just in conducting essential discussions regarding the relationship between objects but also in performing the connections between different existing bodies of work and the future. Moreover, when approaching the exhibition, Clark felt a disciplinary imperative not just to showcase Cristobàl Balenciaga as a subject but also to represent its modus operandi. Indeed, it was about discussing attitude as much as facts and content, increasingly highlighting the relationship between fashion and heritage. The exhibition was highly theoretical, as highlighted by the assumption that Judith Clark’s curatorial approach does not rely on the fabrication of recreations of things that “might have been.” Instead, it focuses on acknowledging and consistently allowing the public to perceive the artefact as it is in the archive or to better comprehend specific inner characteristics of it through the use of “props” designed to amplify the narrative resonance.

“The intervention is only real for me if it’s based on something real or recovered, I'm not in the business of pretending, I’m into the art of alluding-to, it is different. So it’s like close reading the archive. It’s like saying “this is a black and white photograph, but I want to make it important […] what are all its representation possibilities?” We could portray what might have been the colour of the 1950s, but it would actually turn out to be false because we cannot rely on critical evidence, as the archival photography is in black and white. And so you can make it important, differently by putting a spotlight on it. You could have it as a huge blown up image, as was so fashionable to do in the 80s. Nowadays, you can make it relevant with a digital scan and then allow zooming in on it, and so on. In one particular case I built a 3D installation in greyscale “after” the small photograph in the archive - bringing exhibition-making tools to the table to alter the focus on one or other element as we are used to doing with the act of ‘zooming in’”

The analysis of the staging model mainly focused on the use of props as visual “captions”. For the exhibition, Clark designed a double narrative within the curatorial project to explain both the evolution of Balenciaga’s designs in the form of archival heritage and its historiography, what was referenced as external museographic, artistic, academic, and technological parentheses that were developed to reference his work after 1968. For Clark, exhibition-making functions as a form of residue, an attempt to reintroduce the essence of a spatial experience (whether anachronistic or not) into a curatorial narrative. This particular project stimulated deeper reflection on how associative meaning is constructed within the exhibition design. Similarly, the conceptual focus on Balenciaga’s evolution of volume as a key attribute led to material experiments with the aim of representing the unseen - not only absent garments, but the space between dress and body, “explained” by Clark with the design of a prop:, a transparent PVC replica of a dress to show the void created under the dress, its extended volume. Even though the exhibition was arranged in chronological order, the presence of these props offered “curatorial deepening” to aid the acknowledgement of transversal perspectives that involved different actors and contexts within the exhibited concept. This topic led to another critical approach during the conversation. The need to build props was derived from the creative opportunity afforded by the simple fact that all archives have gaps in their collections of artefacts. Indeed, there were a couple of cape dresses selected in the initial phase, and Uria reported that, while the museum had three, the original series was composed of four. For this purpose, Judith Clark designed a plain silhouette made by tyvek, the synthetic material with inherent resistance to microbial penetration used for conservation, to ‘materialise’ the gap such that the three capes could be understood against the extended context provided by the silhouette of the fourth. The author emphasizes the importance of carefully presenting the nature of curatorial gaps and how to represent such “holding patterns” within an exhibition. For example, placing three capes together in a cluster might suggest a linear progression, implying the designer created one after the other. In contrast, the inclusion of a silhouette or an image can signal an absence, highlighting a gap within the archive. Conceptually, this curatorial strategy was explored in a number of ways in the exhibition, supported by the museum. Not only did the company grant the author permission to feature a blank Tyvek cover as a symbolic presence, but it also granted access to historical information that provided the basis for the story.

Often, props constitute material to be added to the permanent collections of Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums (GLAMs), being treated like objects belonging to the museum but with a different nature, during the exhibition path, with their own description on the guide leaflet. This was also the curatorial choice within this case-study since the props were fundamental in adding key content to the narrative. The discussion then converged on the role of the prop as an object that acquires autonomy, becoming a vessel for the memory of an exhibition concept and a specific moment within the curatorial process. In this sense, the prop transcends its functional role and embodies a form of curatorial thinking. It is at this intersection–where the prop shifts from supportive element to conceptual artifact–that the critical debate emerges.

In thinking about the experience model, considerations about the “a posteriori” user experience were provided. A question was raised regarding the extent to which non-specialist audiences might access the multilayered narratives embedded within the exhibition. The concern arose from the potential difficulty such audiences may encounter in interpreting the curatorial digressions and associative references conveyed through props–elements that are not always fully explained in accompanying interpretive materials such as guide leaflets. This was acknowledged as a fundamental and unresolved issue within exhibition practice, underscoring the broader recognition that exhibitions often contain layers of meaning that may remain inaccessible or ambiguous, even to informed viewers and indeed how didactic processes work as atmosphere.

“This is the million-dollar question. Sometimes, it might refer for example to a gold frame that gives importance to something. People don’t usually return from an exhibition saying, “I don’t understand the significance of the gold frame.” But, they’ve experienced the painting as having been elevated by this ornate frame. So, does it truly matter if one understands whether the gold frame is from the 1830s or the 1920s? Well, it matters to us, perhaps, but perhaps not always to everyone. It might be just as much about reconnecting us creatively to a different period and a different mindset. Essentially, there isn't a singular correct way to perceive an exhibition. There is no right or wrong, but there are emotions involved and every lens through which we ask the visitor to look brings with it new associations.”

The final important highlight of this exhibition relates to its digital twin published on the Museum’s website as a virtual tour1. This material continues to offer online visitors the opportunity to experience the exhibit, offering a smooth overview of the setting with the possibility to dig into the showcased objects’ explanation. The virtual tour greatly enhanced Vandi’s direct study of the showcased pieces by providing interactive features and comprehensive information accompanying the exhibits, allowing for a more thorough examination and visual understanding of their significance. Even from Judith’s remarks, it emerged that the Cristòbal Balenciaga Museum is very receptive to the significance of digital technology implementation. Indeed, it is part of a future strategy to involve digital technologies as essential levers for augmenting the dissemination of their offers and, contrary to their non-easily accessible geographical location, their immense impact on and relevance for fashion heritage.

Homo faber: fashion inside and out

As a consolidated pattern, following Vandi’s analytical breakdown of the exhibition design into narrative, staging, and experience models, Judith Clark provided additional details that complemented and expanded upon the ambitions of the project, offering insights that were previously beyond Vandi’s knowledge.

The second selected exhibition was part of the “Homo Faber. Crafting a more human future” event thus, even though the curator was asked to work independently and make all the dedicated choices without explicit commissions, the ambitious nature of the event brought about the idea that something needed to be promoted to several heterogeneous visitor demographics. The Homo Faber initiative was created to support and create a cultural movement to value excellence in craftsmanship moving the concept and culture of craftsmanship to the future (rather than nostalgia), resonating around its evolution, and Judith Clark’s exhibition was contextualised to showcase what fashion craftsmanship is about and can become. This aspect allowed the curator to have more freedom to use the recent past in terms of garment choice, with a unique take on the alchemy of craftsmanship. Indeed, instead of having lots of people in-situ working directly on their craft–as many of the Homo Faber’s sections provided–Clark concentrated on a themed presentation of their work which is the technical and manufacturing know-how materialised through fashion garments. This curatorial choice and direction toward the future also brought her to resist the nostalgia of exhibiting the kind fo decoration associated with classic ball gowns related to costume and couture, but transposed into the present, selecting garments where the ‘raw’ material was still visible as a canvas to exquisite embellishment.

The curatorial approach was considerably shaped by the spatial and material constraints of the assigned venue–a disused swimming pool. The environment challenged the exhibition of textiles, particularly due to issues of humidity and uncontrolled natural light, both of which rendered the space inherently inhospitable to fragile materials. These conditions necessitated a reconsideration of the overall exhibition protocol. Even though UV filters and structural interventions were undertaken to mitigate environmental risks, curatorial decisions prioritized artifacts less susceptible to light damage. Nevertheless, the display of delicate printed textiles or historical garments was precluded. The material selection was thus inextricably tied to the specific qualities of the site: Venice’s late-summer light and abundant illumination entering the venue from a garden adjacent to the lagoon. In this instance, the framework’s narrative and staging models framed an integrated system, informing and reinforcing each other. The emptiness of the pool–with its connotations of absence and abandonment–was deliberately integrated into the theme of the exhibition. This spatial void resonated with broader theoretical reflections on museums and fashion exhibitions, particularly those articulated by Elizabeth Wilson (Wilson, 2022), who links such emptiness to a sense of stillness and mortality that characterizes the museological experience of dress.

Hence, in this aseptic setting, the curator felt the need for an activation. Playing with the metaphor of the “inside and out,” she brought the interior (considered as the craft technique) out, arranging the garments based on their manufacturing characteristics. Then, reversing the process, the exploration regarded how the outside space could enter the swimming pool, and how to enable the free association with the water outside in the lagoon. This reflection led to the decision to introduce wooden walkways inspired by the characteristic waterways of Venice, with careful attention to the materiality and visual language of the city’s piers. However, once the raised platform was installed, it became apparent that its alignment with the pool structure did not accurately convey the spatial reality of a full pool, as people do not typically walk on the ground of it. Consequently, the curatorial intervention was prompted to find a device to perceptively mark the absent water level. This led to a collaboration with milliner Stephen Jones.

Being inspired by Jones’s “Wash n’ go” hat–a transparent hat that looks like a splash, she asked him to create headdresses from scratch that mimicked a splash in the pool, of course, on a larger scale and tailored to fit a horizontally positioned ‘swimming’ mannequin. Since the material had to resemble water, it was a type of plexiglass that could be folded and shaped, achieved from melting the acrylic. The introduction of this sculptural yet in-motion element functioned as a spatial activator; it was observed that a singular, well-placed gesture capable of suggesting movement could animate the entire environment, reinforcing the narrative and experiential coherence of the exhibition.

Clark’s collaborative attitude toward exhibition-making is something that emerges as relevant for this case, too. Indeed, practitioners and designers such as Stephen Jones–one of the most renowned and radical milliners of modern fashion–, the hair artist Angelo Seminara (using raw wicker as hair to continue the craft-theme), and Naomi Filmer, the jewellery designer who frequently flanks Clark’s curatorial practice, were involved in the project.

Another curatorial strategy that effectively established a dialogue between artefacts and viewers involved the spatial positioning of the mannequins to face one another. This approach–drawn from the exhibitionary principles associated with Diana Vreeland’s legacy (Clark, 2012), which emphasize the activation of space through relational positioning–rejected chronological ordering in favour of aesthetic affinity.

“Rather than including the craftspeople in the room performing their metier, I really believed because we were talking about meticulous craft, I needed to let the finished objects have the last word.”

Craft itself was positioned as the focal point of interpretation. This objective was pursued, for instance, through the deliberate grouping of mannequins dressed in garments composed of the same material. Such repetition directed the viewer’s attention to the nuances of each technique and material manipulation. For example, when three garments in straw were exhibited in proximity, the variations–such as weaving, raw finish, and embroidery–became immediately apparent, encouraging a close and comparative interpretation of artisanal techniques. This impression was applied to other design components, such as hairstyling, which featured bespoke interventions by Angelo Seminara. The end effect was an immersive curatorial setting in which material consistency inspired inquiry, causing spectators to think not only of the finished piece, but also wonder about the procedures and gestures that created it.

Through a series of carefully orchestrated associative elements–including embroidered mannequins, garments, accessories, and wigs–the exhibition conveyed a layered narrative that extended beyond the figure of the fashion designer. The curatorial strategy highlighted the multiplicity of artisans involved in the creation process of the exhibition itself, working across various domains and geographies. Despite the absence of live demonstrations or digital media offering behind-the-scenes perspectives, the exhibition model prioritised an experiential atmosphere grounded in contemplation and close observation.

During the analytical phase of the exhibition study, it was noted that conventional entry materials such as wall texts or printed guides were not present. Instead, the exhibition incorporated the presence of trained mediators referred to as “Ambassadors”–young artisans from across Europe who had been specifically prepared by the curator to guide visitors and articulate the craftsmanship on display. This strategy reinforced the emphasis on interpersonal interaction, privileging human engagement through observation, inquiry, and dialogue. Complementing this, the exhibition replaced standard didactic labels with handwritten captions tied directly to the mannequins. These tags, referencing the artisanal numbering system developed by Maison Margiela, focused on technical data and production-specific insights (such as the number of hours the embroidery took, for example,), thereby reinforcing the curatorial intent to centre the exhibition experience on the material and procedural dimensions of craft.

Discussion: the role of technologies as strategic enhancers for curatorial practices

In light of the results presented, the insights advanced in this discussion are of a conceptual nature, grounded in practice-based dialogue and reflexive observation rather than in empirical validation. While the Balenciaga and Homo Faber exhibitions served as points of departure for articulating the Narrative–Staging–Experience framework, the following considerations on possible digital technologies applications are necessarily speculative, intended to outline possible trajectories rather than to document concrete implementations.

The discussions should therefore be understood as an interpretive contribution, one that invites further empirical testing and broader application in future research.

A key outcome of the analysis is the observation that the design of curatorial practice could extend well beyond traditional structuring mechanisms such as chronology or visual taxonomy and runs instead as a connection between the three models identified as key through the framework. Indeed, while the Balenciaga exhibition adhered predominantly to temporal sequencing and Homo Faber to visual affinities, both employed what can be termed “exhibition prosthetics”–design elements that facilitate the articulation and amplification of the objects’ layered meanings in the space and through the visitors experience. In Judith Clark’s curatorial methodology, such prosthetics are identified as “props” or “attributes,” conceptualised as artefacts or architectural features purposefully designed to serve as interpretive portals. These elements do not merely complement the objects on display; rather, they function as narrative devices that re-mediate, complicate, and contextualise fashion artefacts by drawing out otherwise tacit layers of meaning. These props operate as what might be described as “curatorial deepenings,” aiding in the viewer’s recognition of fashion cultural capital. They engage in metaphorical acts of mediation that situate garments within broader socio-cultural, historical, and material contexts. The narratives constructed through such interventions often reference:

• The semiotic and cultural meanings associated with the body and its representation;

• Historical contexts and biographies of key figures within the fashion system;

• Creative processes and ephemeral materials linked to collection development;

• Craft practices tied to intangible cultural heritage (ICH) and material culture;

• Industrial and technological processes embedded in national or regional histories (Vandi, 2024)

Clark’s curatorial practice can be situated within what was termed a “critical approach” (Vacca and Vandi, 2024) wherein exhibition-making is not conceived only within a didactic framework but seen as a multidimensional interpretive space but as a multidimensional interpretive space. This framework privileges associative, poetic, and metaphorical connections between objects, thereby allowing for open-ended viewer engagement. As Clark herself asserts, curating involves “creating sympathetic allegiances between objects, investing them through association.” She views exhibitions not as linear narratives but as spatialized theoretical constructs–“like reading a piece of theory in 3D” (Clark, 2017, p. 150).

This perspective was further elaborated in her interview with LoScialpo, where Clark articulated the curatorial choice between explicit textual explanation and spatial-metaphorical evocation: “As an exhibition-maker, you have to decide: do you write a caption saying ‘Anna Piaggi loved typography,’ or do you build a cabinet shaped like an A? You are always making choices about how you will communicate the material – I like the ambiguity of creating an impression rather than stating a fact.” Such ambiguity is not indicative of vagueness but reflects a deliberate strategy to engage viewers affectively and imaginatively, thereby enriching the narrative potential of the curatorial space.

These results still demonstrate how, in contemporary exhibition design, an implicit hierarchy persists wherein the physical object remains central, surrounded by secondary interpretative elements–whether spatial, textual, or increasingly, digital. As exhibitions move from thematic and curatorial extension towards more immersive and reflexive interactions, new vectors of mediation and recognition emerge. The incorporation of digital elements challenges assumptions of traditional narrative, staging, and experience paradigms, raising questions of whether digital elements replace material props or instead become added to them to expand their conceptual and experiential scope. Such a shift–from object-based mediation to digitally enhanced re-mediation–necessitates that curatorial methodologies be reconsidered to include hybrid experiences that break outside material constraints. Rather than displacing materiality or the affective dimensions of space, technological grafting can serve to amplify the associative knowledge and metaphorical qualities that are inherent to fashion artifacts on display. Moreover, this dimension is further amplified when considering the inherently hybrid nature of fashion, which, beyond being an object-based discipline, is embedded within a dense network of visual, textual, and audiovisual representations. These diverse modes of remediation reflect the multifaceted complexity of the fashion system, which encompasses not only the tangible features of products and craftsmanship but also the domains of communication, branding, and marketing.

In light of this, interactive digital layers can be used to “animate” props following the narrative, staging, and experience model, not by literalising their meaning, but by digging into their embedded heritage.

Based on the results outlined in Vandi’s PhD research, three conceptual directions have been identified through an analysis of the impact of technologies on the three models of curatorial practice, each closely connected to and shaped by Clark’s personal perspective. It is important to pinpoint that the insights advanced in this discussion are of a conceptual nature, grounded in practice-based dialogue and reflexive observation rather than in empirical validation. While the Balenciaga and Homo Faber exhibitions served as triggers to extrapolate Clark’s curatorial practice and validate it through the interpretive framework, the following considerations on possible digital technologies applications are necessarily speculative, intended to outline possible trajectories rather than to document concrete implementations.

The discussions should therefore be understood as an interpretive contribution, one that invites further empirical testing and broader application in future research.

Narrative model: collaborating

Applying specific technologies to the narrative model is mainly done to answer the need of curators to narrate and explore more extensively all the peculiar and fundamental facets of the chosen object, investigating whether technology is configured as an agency to graft narrative layers to physical objects or to substitute them directly.

Revisiting the collaborative configuration central to Clark’s curatorial methodology, the integration of computational technologies introduces a novel agency into the curatorial process, functioning not merely as an instrument but as an adaptive epistemic partner. Had the curatorial teams involved in the two analyzed exhibitions been able to access an interconnected dataset of linked data (Bizer et al., 2023) –drawing from proprietary museum and archival databases capable of revealing previously unexplored associations–this would have further amplified the evocative power of the displayed objects. Such a resource could have suggested additional thematic linkages, more systematically integrating the multiple actors, semiotic and socio-cultural meanings, as well as the creative, artisanal, and industrial processes that collectively constitute fashion’s heritage. While this scenario remains hypothetical within the scope of the present study, it illustrates the speculative potential of computational collaboration in shaping future curatorial narratives. Specifically, machine learning algorithms and advanced data-driven systems can be deployed to assist in the selection, classification, and narrative construction of artefacts within an exhibition context. These systems, trained on large-scale, structured and unstructured datasets from institutional archives, museum collections, and open-source repositories, facilitate the rapid detection of latent connections, thematic correlations, and previously unrecognised curatorial narrative paths (Manovich, 1999; Kaplan and di Lenardo, 2017). Through their ability to automatically categorize objects by metadata, visual similarity, provenance, or semantic association, these technologies optimize and ignite the preparatory phases of curatorial work. This collaborative effort mostly alleviates the constraints arising from temporality and geography that sometimes limit and hinder the ability of curators to conduct parallel research on different archives and thus makes knowledge production more efficient without eliminating essential curatorial intentionality. Lastly, such collaboration of humans and machines expands the curatorial horizon towards a post-archival logic, where digital infrastructures not only support but actively shape interpretive structures and narrative coherence in the exhibition environment.

However, the successful implementation of such computational cooperation requires the existence of complete, structured, and accessible digital collections–an area in which many cultural institutions, notably those in the fashion industry, are considerably underdeveloped. Despite the growing recognition of fashion as a key component of cultural heritage, the archival infrastructure in this field is frequently fragmented, with corporate collections being unorganized, inconsistently classified, and completely unavailable to both researchers and the general public. The lack of established digital inventories and protocols to organize and link metadata impedes not only the incorporation of fashion artifacts into larger cultural narratives but also the activation of digital technologies capable of analyzing and computing these materials. As a result, efforts in organising and digitising archival collections are now mandatory to enable interoperability between institutions and curators, and facilitate the design of augmented narrative systems that capture the full complexity and richness of fashion’s material and immaterial legacy.

Staging model: extending

It has been demonstrated that remediation practices activated by technologies create new spaces and contexts for the representation of fashion knowledge, introducing new temporal dimensions to the mise en scène.

As a first layer of technological integration for the staging model, the use of AR and QR codes as interactive labels embedded directly within the exhibition layout allows curators to perform behind-the-scenes stories, oral histories from artisans, or archival materials directly connected to the displayed objects. In doing so, the props are transformed into multisensory nodes–both poetic and informative–that eventually guide visitors along non-linear, immersive trajectories of meaning-making. Crucially, within a critical curatorial framework, such technologies are not employed as mere tools of entertainment or hyperrealism. Instead, they need to be conceived by curators as conceptual extensions of the exhibited objects themselves, deliberately grafted onto the narrative to complicate rather than simplify the interpretive experience. When used with intentionality, digital tools can support what Clark has described as the production of impressions rather than straightforward facts. By providing deeper layers of contextualization and preserving interpretive openness, they enable the objects on display to preserve their metaphorical intensity. Secondly, these technologies expand the epistemic and spatial scope of the exhibition (Windhager et al., 2019; Lupo et al., 2023). They support curators in showcasing the magnitude and richness of the archive, offering access to a broad array of resources that could not be physically displayed due to constraints of fragility, space, or format (e.g., born-digital content). Echoing the curatorial strategy adopted in the Homo Faber exhibition–where handwritten tags inspired by the Maison Margiela numbering system foregrounded the material and procedural dimensions of craft–the integration of QR codes or interactive digital tags could operate as a conceptual extension, further amplifying the perception of craftsmanship and its enduring temporalities. By linking garments to video materials and other forms of digital mediation, such devices would not only render visible the tacit knowledge and time-intensive labour embedded in artisanal processes, but would also evoke the broader horizon of preservation practices, thereby reinforcing the curatorial narrative through technologically enhanced modes of staging.

This model, enabled by digital access, increases the narrative depth of the materials on display on the one hand, but it also amplifies the exhibition’s staging potential, effectively extending its spatial boundaries. Through personal devices or audiovisual panels installed in the pathway, visitors may explore the dimensional vastness and depth of investigation of the archival repositories and thus understand the complexity and layering of the narratives embedded in the exhibits. In this way, the exhibition serves as a spatial extension–layered and intellectually stimulating–that can engage both emotionally and cognitively (Vandi, 2023). In this context, by turning to data visualization techniques, curators can visually spatialize the often implicit connections between different artifacts, whether tangible or intangible, or not on display. Indeed, data visualization offers approaches to appreciation of fashion heritage that deviate from the close reading of the object that nonetheless can be enabled with other technologies, but offer cross-cutting readings of the archival holdings that involve dimensions such as (i) spatiality and geography through maps, heatmaps, and geographic projections, (ii) correlations between elements through networks, connections, and dependencies, (iii) different numerical and temporal variables, and (iv) category dimensions such as classes and labels mapped through color-coding, distribution and proportions charts (Burdick et al., 2012; Drucker, 2014; Esposito, 2022). These new approaches increase the need for interdisciplinarity within the curatorial team and open up the dialogue and the need for the training of hybrid professional figures–individuals who possess a deep understanding of cultural heritage and its significance within the fashion system, while simultaneously demonstrating proficiency in technical methodologies. Such profiles must be equipped to engage critically and creatively with digital tools, computational systems, and coding environments typically associated with engineering and data science.

Experience model: augmenting

Reasoning about the technological application of the Experience Model means understanding how fashion knowledge can be expanded and understood by both professors and industry insiders, but also by average users. Technologies have the ability to represent what the naked eye cannot perceive by looking at a displayed artefact (Vandi, 2022; Angeletti et al., 2024); they offer researchers, archivists, and the public the tools to closely examine the objects’ material properties, construction techniques, oral testimonies associated with their making, and the stories of those who once owned them. As we move along the reality–virtuality continuum (Milgram and Kishino, 1994), the representational capacities of these tools evolve. Mixed Reality (MR) and Virtual Reality (VR) integrations enable garments, which are inherently designed to be worn by moving bodies, to be experienced in motion and within simulated reconstructions of their original contexts (Vaccari et al., 2020). This allows for a more embodied and situated engagement with the artifacts, counteracting the static and often decontextualized modes of display common in museum settings. But the full understanding of the artwork implies that clothes were conceived to be dynamically worn and they need to be appreciated in motion, adorning the wearer, as opposed to the stillness of a rigid mannequin. The concept of movement is one of the most important characteristics that needs to be explored (Angeletti et al., 2024) since, unlike static artworks such as paintings, it restores a 360° perception given by the interplay between fabrics and textiles, shapes, and the body of the wearer. Furthermore, digital clothing replicas can be thoroughly examined, including their interior structures, thanks to VR and MR technologies. With the use of these technologies, clothing can be seen in an “exploded view” (O’Neill, 2021), displaying the individual pattern components along with manufacturing details, and enabling a thorough examination of the pattern-making and assembly process when approaching the human body.

Extending Clark’s critical approach to curating–in which exhibitions are conceived not as linear narratives but as multidimensional spaces animated by ‘props’ and spatial metaphors (Clark, 2017) that invite viewers to engage through affective and interpretive openness–the ongoing transformation of exploratory strategies for representing fashion heritage suggests compelling opportunities for renewing this serendipitous mode of inquiry. In particular, the application of generative AI grounded in text and image production offers novel trajectories for augmenting and reconfiguring such curatorial practices. Just as props act as conceptual and affective portals within the exhibition space, generative AI systems trained on the visual and textual ephemera of fashion operate as digital props, enabling new modes of interaction within archival platforms. Referring to Barthes’ distinction between ‘written clothing’ and ‘image clothing’ (Barthes, 1990), these AI-enhanced systems do not merely retrieve documents, but learn from the layers of fashion’s communicative apparatus - texts, photographs, drawings, videos - materialising the languages through which fashion is expressed and understood (Manovich, 2021; Manovich, 2023; Anantrasirichai and Bull, 2022). In this way, they offer users synaesthetic and dialogic ways of exploring the archive, favouring dialogic and synaesthetic research trajectories over rigid archival taxonomies (Rizzi and Vandi, 2023). This paradigm shift - from object-based structuration to conversational and experiential activation - reflects the evolution of curatorial methodologies towards immersive and reflexive practices. Just as curators use spatial and material interventions to bring out the sociocultural meanings inherent in clothes (Haas, 2003), AI interfaces can reveal otherwise unspoken connections in a brand’s history, enabling designers, practitioners, researchers, or the general public to interact with heritage content in a more intuitive and affective way. Both the exhibition and the augmented archive thus become performative environments in which the material and immaterial legacies of fashion are not only preserved but continuously reinterpreted and reanimated through ever-evolving modes of mediation (Schnapp, 2013; Schnapp et al., 2024).

In this scenario, when critically integrated into the proposed curatorial framework, digital technologies can be conceived not only as supplementary enhancements, but as potential agents of narrative construction, spatial design, and experiential engagement. Their integration points towards a reflective, participatory, and speculative curatorial model, capable of evoking the poetic and intangible dimensions of the material culture of fashion, breathing new life into archival content to achieve contemporary resonance. Imagining the archive as an augmented space entrusted to research and imagination implies equipping the public with tools to understand not only what fashion has been, but also what it could become. In this sense, these technologies contribute to the broader intellectual project of gradually rethinking and reshaping the fashion system towards forms of practice that are more critically aware, inclusive, and in tune with the cultural and historical depth from which they emerge.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. Specifically, JC authored the introduction, while AV developed the methodology, findings, and discussion sections, with mutual input throughout the process and final iterative reviews by JC.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Footnotes

1.^ https://www.cristobalbalenciagamuseoa.com/en/discover/digital-exhibitions/online-exhibitions/cristobal-balenciaga-fashion-and-heritage-.html

References

1

Anantrasirichai N. Bull D. (2022). Artificial intelligence in the creative industries: a review. Artif. Intell. Rev.55 (1), 589–656. 10.1007/s10462-021-10039-7

2

Angeletti E. Gaiani M. Palermo R. Garagnani S. (2024). Beyond the physical exhibit: enhancing, showcasing and safeguarding fashion heritage with VR technologies. Digital Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit.32, e00314. 10.1016/j.daach.2023.e00314

3

Barthes R. (1990). The fashion system. University of California Press.

4

Bizer C. Heath T. Berners-Lee T. (2023). “Linked data–the story so far,” in Linking the world’s information: essays on tim berners-lee’s invention of the world wide web. 52 (Association for Computing Machinery), 115–143. 10.1145/3591366.3591378

5

Burdick A. Drucker J. Lunenfeld P. Presner T. Schnapp J. (2012). Digital_Humanities. MIT Press.

6

Clark J. Frisa M. L. (2012). Diana Vreeland after Diana Vreeland: Mostra; Palazzo Fortuny, Venezia, 10 marzo - 25 giugno 2012. Marsilio.

7

Clark J. (2017). “Props and other attributes: fashion and exhibition-making,” in Fashion curating: critical Practice in the Museum and beyond. 1st ed.

8

Drucker J. (2014). Graphesis: visual forms of knowledge production. Cambridge, Massachusetts London: Harvard University Press. (MetaLABprojects).

9

Esposito E. (2022). Comunicazione artificiale. Come gli algoritmi producono intelligenza sociale. Milano: Bocconi University Press.

10

Evans and Vaccari (2019). Il tempo della moda. Translated by Barbuni. Milano: Mimesis.

11

Haas J. (2003). The changing role of the curator. Fieldiana. Anthropol. (36), 237–242.

12

Jorgensen L. (2011). Participant observation. SAGE Publications, Inc.10.4135/9781412985376

13

Judith Clark and Amy de la Haye (2014). Exhibiting fashion: before and after 1971. 1st ed. Yale University Press.

14

Kaplan F. di Lenardo I. (2017). Big data of the past. Front. Digital Humanit.4, 12. 10.3389/fdigh.2017.00012

15

Lupo E. Carmosino G. Gobbo B. Motta M. Mauri M. Parente M. et al (2023). “Digital for heritage and museums: design-driven changes and challenges,” in IASDR 2023: Life-Changing Design, Milano10.21606/iasdr.2023.397

16

Manovich L. (1999). Database as symbolic form. Convergence Int. J. Res. into New Media Technol.5 (2), 80–99. 10.1177/135485659900500206

17

Manovich L. (2021). Artificial aesthetics. Medium. Available online at: https://medium.com/@manovich/artificial-aesthetics-chapter-1-even-an-ai-could-do-that-b75a6266da03 (Accessed February 1, 2022).

18

Manovich L. (2023). “Seven arguments about AI images and generative media,” in Artificial aesthetics: a critical guide to AI in art, media and design. 2nd ed.

19

Marchetti L. (2016). Fashion curating. 11th EAD Conf. Proc. Value Des. Res.10.7190/ead/2015/161

20

Milgram P. Kishino F. (1994). A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. (12), 1321–1329.

21

O’Neill A. (2021). Exploding fashion: making, unmaking, and remaking twentieth century fashion. 1st ed. Tielt: Lannoo.

22

Rizzi G. Vandi A. (2023). “Artificial intelligence in fashion design education: redefining creative processes towards designer-ai co-creation,” in 16th annual international Conference of education, Research and innovation, seville, Spain, 3905–3912. 10.21125/iceri.2023.0977

23

Schnapp J. (2013). “Animating the archive,” in Design and cultural heritage, Archivio animato, 63–80.

24

Schnapp J. Vandi A. Rizzi G. (2024). “L’Archivio dal vivo. Dal progetto all’Algoritmo,” in Gianfranco ferré dentro l’Obiettivo. 1st ed. (Bard: Forte di Bard Editore), 149–171.

25

Tamarkin E. (2022). Apropos of something: a history of irrelevance and relevance. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Available online at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/A/bo138499116.html (Accessed June 29, 2025).

26

Trocchianesi R. (2022). “Narrazioni plurali intorno all’oggetto: modelli narrativi e paradigmi allestitivi,” in Storytelling. Esperienze e comunicazione del Cultural Heritage. 1st ed. (Bologna: Bononia University Press).

27

Vacca F. Vandi A. (2024). Digital curatorship practices for fashion-heritage experiences. Mimesis J.13 (2), 597–608. 10.13135/2389-6086/9909

28

Vaccari A. Franzo P. Tonucci G. (2020). ‘Mise en abyme. L’esperienza espansa della moda nell’età della mixed reality. ZoneModa J.10 (2), 75–89. 10.6092/issn.2611-0563/11804

29

Vandi A. (2022). “Digitalising fashion culture: impacts on historicised and contemporary production and consumption practices,” in Storytelling. Esperienze e comunicazione del Cultural Heritage. 1st ed. (Bologna: Bologna University Press ARTE. Collezioni Luoghi Attori), 309–319.

30

Vandi A. (2023). Dealing with objects, dealing with data. The role of the archive in curating and disseminating fashion culture through digital technologies. ZoneModa J.13 (1S), 155–168. 10.6092/issn.2611-0563/17935

31

Vandi A. (2024). “Archiving fashion futures,” in Design-driven curatorial practices fostering innovation in CCIs. Politecnico di Milano: PhD Thesis.

32

Vänskä A. Clark H. (2017). Fashion curating: critical practice in the museum and beyond. Bloomsbury Publishing.

33

Wilson E. (2022). Unfolding the past. London New York Oxford New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

34

Windhager F. Federico P. Schreder G. Glinka K. Dork M. Miksch S. et al (2019). Visualization of cultural heritage collection data: state of the art and future challenges. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph.25 (6), 2311–2330. 10.1109/TVCG.2018.2830759

Summary

Keywords

fashion curation, curatorial practices, exhibition design, digital technology, design research, cultural heritage

Citation

Vandi A and Clark J (2025) Fashion curation in dialogue. Toward a framework for codifying technology-enhanced curatorial practices in fashion. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 15:15196. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2025.15196

Received

30 June 2025

Accepted

05 September 2025

Published

15 September 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Vandi and Clark.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Angelica Vandi, angelica.vandi@polimi.it

ORCID: Angelica Vandi, orcid.org/0000-0002-3627-0059; Judith Clark, orcid.org/0009-0009-0887-2763

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.