Abstract

This article addresses the complex and multifaceted relationship between Cultural and Creative Industries (CCI) and wellbeing, an evolving field of study that still lacks a solid and integrated analytical foundation. Through a multidisciplinary approach, the paper reviews a wide range of theoretical contributions and empirical studies to assess the potential of CCI as drivers of individual and collective wellbeing. Beyond their economic significance, CCI are considered in light of their capacity to generate symbolic value, stimulate creativity, foster innovation, and shape cultural participation. A conceptual framework is proposed to capture the main transmission channels through which these industries influence the various dimensions of wellbeing—including material conditions, health, education, social cohesion, environmental sustainability, and life satisfaction. The analysis also acknowledges the possibility of counter-effects and highlights the importance of contextual and enabling factors in determining outcomes. Drawing from recent evidence, the article suggests that CCI can play a key role in promoting inclusive, resilient, and sustainable development. However, it also stresses the need to move beyond partial or fragmented findings by advancing more robust empirical research capable of capturing the complexity and diversity of impacts across territories.

Introduction

The relationship between Cultural and Creative Industries (CCI) and wellbeing is a subject of growing interest. Both from the academic and institutional spheres, several positive effects of CCI on the economy and society have been suggested in recent years (Ateca-Amestoy et al., 2021). However, causal empirical evidence that can be generalised to different contexts is still scarce in many areas. Nor is there a sufficiently well-established theoretical understanding of the transmission chains through which the impacts attributed to CCI are generated.

Hence, this paper aims to situate the state of the art, through an extensive review of theoretical contributions and empirical studies, as well as to outline a theoretical framework of the main transmission chains of the impacts of CCI on wellbeing based on a multidimensional conception of the latter.

Since it is not the purpose of this paper to contribute to the conceptual or labelling debate on what the ‘cultural and creative industries’ are, or what is meant by ‘wellbeing’, but rather to focus mainly on their linkage, this issue will be briefly touched upon. It is considered that the lowest common denominator of the different definitions, and what essentially defines CCI, is that they produce goods and services with an important symbolic (i.e., cultural) content and that they require a significant input of human creativity for their production.

Regarding wellbeing, a multidimensional view is assumed based on the capabilities approach, i.e., focusing on everything that contributes to expanding the opportunities and capabilities needed to live a life worth living (Sen, 1985). In this sense, any holistic conception of wellbeing should include at least the “three essentials” of the first UN Human Development Report (UNDP, 1990) (i.e., a long and healthy life, adequate material conditions and access to knowledge), plus the fourth pillar mentioned in the report, which refers to life in community. To this, two cross-cutting dimensions should be added, namely, that these objective conditions are effectively valued by individuals and the community (i.e., subjective wellbeing) and the sustainability of wellbeing over time (Stiglitz et al., 2010), not only in ecological terms but also in social (Dempsey et al., 2011) and economic terms, considered through the other pillars.

This categorisation of pillars of wellbeing will be used to structure the review of evidence on the effects of culture and the CCI on the different components of wellbeing in an orderly manner. Naturally, this multiplicity of components and the multidimensional nature of wellbeing requires a multidisciplinary approach. Given the variety of topics to be addressed, the most relevant contributions are used in each case, regardless of the discipline from which they originate. For example, to address the effects of CCI on social cohesion and civic engagement, it will be necessary to draw on contributions from sociology or political science; for the effects on the economy and employment, economics; for the effects on health, medical sciences; for the environmental effects, environmental sciences; for the effects on subjective wellbeing and life satisfaction, psychology; etc. Particular attention is given to studies that combine different disciplines and perspectives.

First, some previous theoretical contributions on the nexus between CCI and multidimensional wellbeing will be reviewed. Second, the empirical evidence available so far on the effects of culture and CCI on different dimensions of wellbeing will be compiled. Third, from this theoretical and empirical basis, a comprehensive conceptual and analytical framework on the role of CCI in fostering wellbeing will be constructed. Finally, some conclusions and further implications will be outlined.

Decoding the relationship between cci and wellbeing: theoretical background

Some initial remarks

As no one will be unaware, the relationship between CCI and wellbeing is a matter of extreme complexity. Great authors such as Adam Smith, William Stanley Jevons, Alfred Marshall, John Maynard Keynes or Lionel Robbins, dealt with the issue of cultural goods and services as part of the economic and social structure, often without understanding the full complexity of their role as value generators. But even so, they all agreed that access to culture is essential for the development of a good society (see Aguado et al., 2017 for a more detailed discussion).

The first thing to point out is that, far beyond the instrumental value of culture to pursue other ends (such as economic development, health, a more cohesive society, or ultimately wellbeing), culture has value in itself. Cultural engagement generates pleasure, arouses emotions and modulates consciences. It meets aesthetic, cognitive, expressive and self-realisation needs. Those that Maslow (1943) placed at the top of the pyramid of needs, regardless of the contributions culture may also make to the needs of lower levels. That is, whether or not culture can strengthen economic activity, social connections or environmental sustainability, it has intrinsic value. Culture makes us live better lives, lives worth living. It does not need other higher purposes to exist because cultural expression is already an end in itself (Ateca-Amestoy, 2021), art for art’s sake. But it may also have other areas of influence. The explanation for this lies not in its intrinsic value but in its instrumental value, i.e., its capacity to achieve other ends through culture, or rather, CCI. As an example, attending a music concert is primarily about enjoying music, feeling pleasure or evoking emotions. But, at the same time, we can benefit from it by stimulating our brain activity, reducing our anxiety level–and thus improving our mental health–or by spending quality time and strengthening bonds with our friends or relatives.

Holden (2009) distinguishes, in addition to intrinsic and instrumental value (the latter implying economic or social benefits), institutional value. This is produced in everything that culture brings in the form of public goods, such as public knowledge or an active civil society. In turn, the Warwick Commission (2015) stated that CCI generate cultural value, economic value and social value (Cunningham and Flew, 2019). The first is equivalent to intrinsic value, while the other two can be considered different forms of instrumental value, depending on the nature of their effects. Also in Holden’s (2009) classification we can consider institutional value as a form of instrumental value. But in this case the benefits produced are of a collective, rather than a privative, nature. However, there are also authors who believe that this value distinction is actually a false dichotomy that should be overcome (Crossick and Kaszynska, 2016; Klamer, 2016). Contributions from the field of cultural heritage management have also delved this debate, emphasising the dynamic nature of these values (Fredheim and Khalaf, 2016; Avrami and Mason, 2019; Pastor Pérez et al., 2021).

While acknowledging that the value of culture and creativity, hence of CCI, goes far beyond their instrumental value in achieving other ends, this paper will focus on the latter, but considering a broad sphere of effects, i.e., multidimensional wellbeing, which to some extent indirectly captures the intrinsic value of culture through subjective wellbeing and life satisfaction. That said, we must move on to conceptualise the relationship of CCI to the dimensions of wellbeing.

Addressing the role of CCI in the economy

A partial approach to the link between CCI and wellbeing starts from the connection between CCI and the economy, i.e., the material conditions of wellbeing. Quite a lot has been written about this. Potts and Cunningham (2008) conceptualise four possible models of the relationship between CCI and the economy. These are the welfare model, the competition model, the growth model and the innovation model.

The first considers that the contribution of CCI to productivity growth is negative. This is based on the cost disease proposed by Baumol and Bowen (1965), which is not without its critics (see Cowen (1996), who considers productivity to be a misleading indicator for CCI). However, CCI would provide other types of values that would make them be considered as “merit goods,” as they enrich education and foster critical thinking, improve social capital and community cohesion, etc. This interpretation would justify subsidies to the industry to sustain it for its goodness (i.e., to promote welfare) but to the detriment of economic growth.

The competitive model instead considers CCI as “just another industry,” with similar effects on both economic growth and utility generation. They would therefore require to be treated in the same way as other industries in public policy.

The third model, or growth model, places CCI as a driver of economic growth. CCI generate new ideas that are transferred to other industries, making them a strategic industry to promote.

Finally, the innovation model considers that CCI are not really an industry per se, but a key gear in the innovative system of the economy. They play a structural role, as do education, science and technology. CCI are ultimately facilitators of evolutionary processes of change. In fact, Potts (2009) renames this model the “evolutionary model,” since CCI are embedded within the Schumpeterian model of economic evolution.

Boix-Domènech and Rausell-Köster. (2018) review these four models and suggest that a fifth scenario could theoretically be envisaged. The four proposed models assume positive or neutral wellbeing impacts. Even the first model, despite the negative impact on productivity, assumes an intrinsic value of CCI that deserves to be preserved through subsidies. But this should not necessarily be the case. The authors hypothesise that the effects could even be negative because of a crowding out effect of other activities that generate more value (assuming the cost disease), because of the abundant precariousness of labour in these industries (Hesmondhalgh, 2010), and due to crippling alienation effects.

In any case, apart from hypothetical scenarios, the authors find evidence consistent with the growth model and with the innovation model, although contrasting the latter empirically is a much more complex task (Potts and Cunningham, 2008). The positive relationship of CCI with economic growth has been confirmed by a number of subsequent research (as discussed below), although there have also been criticisms of positioning it as a policy goal (see Banks, 2018).

The underlying idea of the innovation model is precisely what has sparked interest in studying how CCI affect the rest of the economy. It is heavily influenced by the Schumpeterian theory of long waves, which places innovation (and competition in innovation, rather than prices) as the main force of progress in capitalist economies. The idea that culture and CCI in particular are a systemic enabler of innovation has found considerable currency in the literature. It is argued that they are capable of leading endogenous development models in the territories (Sacco and Segre, 2009).

In the post-industrial era, in which the focus of development moves from physical capital to human capital and knowledge (Bell, 1973), there is a shift from the Marshallian concept of the industrial district. Sacco et al. (2013) propose a new approach of system-wide cultural districts, in which culture plays the role of system activator. In these, the coordination of cultural actors and their complementarity within the multiple value chains to achieve strategic development objectives prevails.

Nevertheless, it is often questioned whether, within this grouping of diverse activities that are the CCI, it is really those of a purely artistic and cultural nature that contribute to innovation and development. Although at first glance it might seem that innovation and productivity gains occur mostly in the more technology-intensive industries, some authors place arts and culture as an integrated part of the same value chain in terms of driving innovation (De-Miguel-Molina et al., 2014). Arts and culture trigger experimentation, which leads to the generation of knowledge, which in turn triggers the emergence of new methods and ideas. These are transmitted to the more peripheral or commercial-oriented CCI, and to the wider economy (Metro-Dynamics, 2020). Along these lines, Asheim (2007) and Asheim et al. (2011) categorise three types of knowledge: analytical (science-based), synthetic (engineering-based) and symbolic (arts-based). It is in the latter that core cultural sectors make their greatest contribution. But it is in the cross-fertilisation between the different forms of knowledge, and building connections between complementary industries, that economic development is triggered. We can see a clear example of this in the video game or the audio-visual industry, where analytical and synthetic knowledge is combined with symbolic knowledge that acts through visual storytelling, musical evocation, narrative arcs or visual aesthetics. The use of architecture, which builds on physics (analytical) and engineering (synthetic), to redefine the uses of space and the imaginary of cities (symbolic), could be another example.

According to Dellisanti (2023), however, not all CCI are knowledge generators. He considers that there are inventive CCI, which apply technological, symbolic and/or artistic creativity, and replicative CCI, which produce mass consumer goods with a creative and cultural base. The former, as knowledge generators, benefit from knowledge-intensive environments, while the latter require access to large markets for their mass production. Both contribute differently to GDP growth on the supply side, and in turn all CCI contribute on the demand side by changing consumption patterns. The results of Dellisanti (2023) confirm that both groups of CCI are engines of growth, each through different channels. Yet territorial characteristics are a relevant factor, as inventive CCI have greater effects in urban regions, while replicative CCI have greater effects in rural areas. Therefore, development strategies based on CCI should follow a logic adapted to regional circumstances and potentials.

The quest for the “creative class”

Another line of argument is that of Florida (2002), Florida (2008), who focuses on the concept of the “creative class” and the capacity of cities and territories to attract it. According to Florida, creative and talented people are the ones who drive growth and create good jobs. In other words, it is not the people who look for the jobs but the jobs that follow the people. Creative people, specifically. The creative class seeks out attractive environments in which to develop that creativity. These are the ones where the three T’s come together: technology, talent and tolerance. Cities’ strategy for development should therefore be to create the conditions to attract and retain the creative class. This line of thought has given rise to several analyses of the conditions for making a city or region appealing, the determinants of the location of the creative class, or how the creative class enhances economic dynamism (e.g., Boschma and Fritsch, 2009; Clifton and Cooke, 2009).

However, this approach has also met with a great deal of criticism (see Peck, 2005). Florida tries to answer the question of how one chooses where to live and work. This is closely linked to the mentality of the USA, with intense internal geographic mobility. But mobility between other places where there are greater cultural differences and where the sense of territorial rootedness is stronger, is much more limited (Miller, 2009; Musterd and Gritsai, 2013). Moreover, basing development on attracting creative people may be beneficial for the region that succeeds, but it comes at the expense of the rest of the territories that lose their creative class. Overall, it would be a zero-sum game (Pratt, 2008). Some authors also criticise that it is likely to confuse cause with consequence, i.e., whether it is the bohemian atmosphere and lifestyle that is the cause of economic growth or rather a symptom (Peck, 2005).

Most criticisms, however, focus on pointing out elitism, potential inequalities and negative externalities (such as gentrification) generated by this model of regional development. It reserves the role of creativity to a few: the leaders, the drivers of the economy, while the rest are mere passengers. The creative class abhors the mundane and time-consuming tasks of social reproduction, but someone has to do them. In the words of (Peck (2005), p. 757), he does not answer to “who will launder the shirts in this creative paradise.” If the aim is to focus on attracting talent from outside, the question arises as to the place of “non-talented” local people. Critics argue that this creates a dual economy where “non-creatives” are left behind.

This approach implicitly conceives creativity as an innate ability possessed only by a select group of people. Since these skills are highly correlated with education and, by extension, income (O’Brien et al., 2016), doing everything possible to please the “creative class” may carry a strong class bias. Indeed, even Florida (2008), in a later development, concedes that this strategy generates economic polarisation and that the creative class is actually a privileged minority.

In view of all this, critics of Florida consider it preferable to devise an endogenous development process that also involves the local population and that, beyond attracting talent, generates it. In other words, it is not a question of attracting the ‘creative people’ by finding out what they want, but of activating people’s creative capacity.

Broadening the view: “it’s not (just) the economy, stupid”

In any case, the creativity processes inherent in CCI do not only play a central role in the economy. Innovation, catalysed through these industries, can be applied to much broader spheres. Creativity makes it possible to completely rethink the way we face societal challenges and find new, inclusive and sustainable solutions. This is pointed out by the European Commission and KEA European Affairs (2019), which highlight the potential contribution of CCI to tackle issues as varied as the circular economy, promoting healthy lifestyles, societal resilience or energy transition.

Likewise, Gustafsson and Lazzaro (2021) point to the contribution of CCI to many societal challenges facing, in particular, Europe. They see their role to be crucial, because of their strong innovative capacity, in four pillars: creativity, cultural diversity and values; cohesion and identity; employment, economic resilience and smart growth; and external relations.

Indeed, there are many areas to which they can contribute. The European Union, in the framework of the previous European agenda for culture, categorised six spillover effects of CCI on the rest of society and the economy, including innovation and productivity, education and lifelong learning, social innovation and wellbeing, tourism and branding, environmental sustainability and regional development (European Union, 2012). Tom Fleming Creative Consultancy (2015) identified through a literature review up to seventeen spillovers (four more were added in a later revision (McNeilly, 2018)), which were grouped into three categories: knowledge, industry and network spillovers. Many of them are directly related to particular dimensions of wellbeing, while others are of a cross-cutting nature and contribute to creating an open and creative atmosphere, conducive to the exchange of ideas and to driving change.

The following section will explore what is known about all these potential effects on wellbeing, i.e., what empirical evidence there is for them, beyond hypotheses. It will start with the effects of culture in a general sense (mainly cultural participation or consumption). Subsequently, it will focus on those works that specifically consider the role and effects of CCI as part of the economic structure.

State of the art: mapping the evidence so far

Impacts of culture on wellbeing

For years, the need to measure the value of culture and creativity in a broader sense (and far beyond market value) has been pointed out (e.g., van der Pol, 2008). Although internationally comparable statistical sources are still scarce, many studies have been carried out to date. This allows us to have evidence of their impacts in more and more spheres of life (Taylor et al., 2015; OECD, 2022).

Starting with a few brief general points, the pioneering study by Matarasso (1997) found that the creative and open environment provided by the arts set the roots for social change. He identified a list with a diverse range of fifty social impacts, which he acknowledged was incomplete. A few years later, Guetzkow (2002) reviewed the then existing literature on the impacts of the arts. He grouped them into three claims: the arts increase social capital and community cohesion; the arts have a beneficial impact on the economy; and the arts are good for individuals. The latter results through improvements in health, psychological wellbeing, skills, cultural capital and creativity. He acknowledged, however, a number of theoretical and methodological limitations, challenges and contradictions. But fortunately, the analyses have become more sophisticated over time.

Next, the different studies identified in the literature will be classified according to the pillars of wellbeing previously defined in the introduction. These are: long and healthy life, material conditions, acquiring knowledge, living in community, subjective wellbeing and environmental sustainability.

Long and healthy life

Health effects are probably one of the most studied dimensions. Fancourt and Finn (2019) published an extensive review for the World Health Organisation (WHO) with almost a thousand references of studies demonstrating positive impacts of arts and culture on both physical and mental health. In a general framework, cultural participation involves a number of varied components that may include sensory activation, evocation of emotions, cognitive stimulation, social interaction, involvement of the imagination or physical activity. These generate psychological, physiological, social and behavioural responses that lead to outcomes in terms of prevention, health promotion, management and treatment of a wide range of diseases. Also Ings and McMahon (2018), for Arts Council England, and Taylor et al. (2015) compiled multiple pieces of evidence in this regard.

In the same vein, there is a new, more up-to-date study review report resulting from the European project CultureForHealth (Zbranca et al., 2022). It includes not only studies on culture and health, but also culture and subjective wellbeing (with identified effects on personal fulfilment and engagement, personal orientation, experiences of emotions and personal evaluations of life), culture and community wellbeing (including effects on social inclusion, school- and work-related wellbeing, quality of built environment and wellbeing, and community development), and culture and COVID-19, although the latter field is beyond the scope of this paper.

Beyond compiling empirical evidence, and seeking rather to explain the mechanisms through which these effects occur, Fancourt et al. (2021), through an extensive review, identified a network of mechanisms for the transmission of multilevel effects (at the micro-, meso- and macro- levels) produced by biological, psychological, social and behavioural processes, which affect physical and mental health both directly and indirectly by modifying health behaviours.

Sacco (2017) points out some macro-level implications that this relationship between culture and health might entail. He argues for a greater involvement of arts and culture with the traditional pillars of welfare policies, namely, the health and social care system, in a ‘cultural welfare’ policy paradigm. Especially in view of the challenge of ageing that particularly affects European countries. Along these lines, Young et al. (2016) review several studies showing the potential of arts interventions to improve the lives of dementia patients, slowing cognitive decline, reducing loneliness and thus enabling healthy ageing. It is worth noting that not only are there small controlled experiments on certain cultural interventions in small groups, but there are even longitudinal studies showing lower mortality caused by greater cultural engagement (Fancourt and Steptoe, 2019).

Subjective wellbeing

Another well-studied effect is that of culture on individual subjective wellbeing, revealing positive impacts (Grossi et al., 2011, 2012; Wȩziak-Białowolska et al., 2019; Verboord et al., 2024), which tend to be higher especially in contexts of high socio-economic development (Tavano Blessi et al., 2016). Wheatley and Bickerton (2019) provide evidence that participation in different cultural activities increases overall life satisfaction, but also satisfaction with health and with leisure. Hand (2018) further finds that the impact on happiness is stronger among those at low levels of happiness.

Similarly, greater perceived wellbeing and lower stress levels (measured by the amount of cortisol in saliva) were found after visiting a historic heritage site (Grossi et al., 2019). Ateca-Amestoy et al. (2021) also observe positive effects on life satisfaction of various forms of engagement with cultural heritage. In fact, when compared to other daily actions, Bryson and MacKerron (2017) find that engaging in various cultural activities (such as attending performing arts or heritage sites) are among the activities that bring individuals the most happiness throughout the day. It should be noted, though, that according to Tymoszuk et al. (2020), in a study with older adults, the effects on wellbeing are only significant if cultural participation is sustained over time, rather than one-off.

Acquiring knowledge

The effects of culture on education have also attracted much interest. Winner et al. (2013), for the OECD, conduct an extensive review of how different forms of arts education (in and out of school) improve students’ performance in non-arts subjects. In particular, the effect of musical activities on students’ skills and academic achievement has been extensively studied (Holochwost et al., 2017; Guhn et al., 2020; Knaus, 2021).

Studies have also been conducted on at-risk youth, i.e., with a low socio-economic status, showing that those more involved with the arts achieved higher levels of success (Catterall et al., 2012), thus contributing to narrowing the educational gap with their peers.

Moving away from the individual analytical prism and focusing on the general educational level of the population of a territory, Crociata et al. (2020) relate cultural capital to human capital, and find positive effects of cultural participation on tertiary education and lifelong learning.

Material conditions

From a territorial perspective, culture as an integral part of urban regeneration strategies is very much present in the literature in recent decades, looking at a range of social and economic impacts on cities. Tavano Blessi et al. (2012) argue that investing in culture as part of urban regeneration processes is a determinant of human and social capital accumulation. Rausell-Köster et al. (2022) even consider and find evidence to suggest that the combination of a number of elements that form the so-called “cultural city” determine the economic performance of cities measured in productivity growth.

In terms of income, the most commonly studied relationship is the inverse: how income level influences access to different forms of culture (e.g., Falk and Katz-Gerro, 2016). Conversely, and at the aggregate level of city, region or country, it is argued that cultural engagement benefits economic growth mainly through two channels: as an enabler of innovation and indirectly through the educational benefits that enhance human capital (OECD, 2022).

However, excluding those works that refer specifically to CCI (which will be discussed in the next section), there are not many other empirical studies on the relationship between culture and income. Although there is certainly a body of research that assesses the economic impact of specific tangible or intangible cultural assets or cultural events (e.g., Plaza et al., 2015; Parga Dans and Alonso González, 2018).

From a broader point of view, Cerisola (2019), for Italy, shows how the stock of cultural heritage has an indirect impact on the economic performance of regions, by inspiring both artistic and scientific creativity. There is also evidence, using data from Catalan municipalities, that a “creative milieu” (following the 3T theory of Florida (2002)) attracts firm creation, both creative and non-creative (Coll-Martínez and Arauzo-Carod, 2017). Following a similar logic, Falck et al. (2018) find that the concentration of cultural amenities strongly attracts high-skilled workers (as also shown by Backman and Nilsson (2018) for Sweden with cultural heritage), and that this has a positive impact on the income of all other workers.

Another line of empirical research, particularly in Europe, consists of successive impact studies conducted on European Capitals of Culture, highlighting the effects on the local population’s perception of the city, self-esteem and pride, as well as the economic effects, although the latter have tended to be somewhat overstated and insufficiently substantiated (Garcia and Cox, 2013).

Living in community

A range of social and community impacts encompassing improved interpersonal relationships, social cohesion, inclusion, sense of belonging and community building constitute the next corpus of work. In this sense, culture acts in two main ways: as a transmitter of meanings and messages that change beliefs and behaviours and generate social awareness; and through the social connectivity that is generated in many forms of community cultural participation.

The documented effects are varied. Stanley (2006) identified, through the discussion of a panel of experts, six social effects of culture, arts and heritage: enhancing understanding and capacity for action; creating and retaining identity; modifying values and preferences for collective choice; building social cohesion; contributing to community development; and fostering civic participation. Arts spaces have been reported to enhance community development (Grodach, 2009), along with the build-up of social capital from arts festivals (Brownett, 2018) or the role of culture in promoting older people’s social connections, inclusion and sense of community, among others (Moody and Phinney, 2012; Teater and Baldwin, 2014).

There is also evidence of how culture affects community building and sense of belonging. As an example, in the case of the European Capital of Culture in 2012 in Maribor, intangible impacts were found among the population such as a stronger sense of reputation and community pride (Žilič Fišer and Kožuh, 2019).

On the other hand, Otte (2019) finds that arts and culture influence social cohesion but distinguishes two distinct effects. What she calls “confirmative arts” reinforce internal cohesion, based on common values, while “challenging arts” foster external cohesion, bridging differences. With regard to the second typology of effects, the role of the arts as a facilitator of cooperative relationships and conflict resolution has been noted (Bang, 2016), as well as an avenue for social inclusion for certain vulnerable groups (Brader and Luke, 2013). In addition, Benediktsson (2012) provides quantitative evidence that students who are more involved in arts and cultural activities tend to form more friendships with people from different cultures and ethnicities.

Recent research has also explored the connection of culture and the arts with civic engagement. Campagna et al. (2020) show that people who are more involved in cultural activities tend to be more engaged in civic life. Related to this, the relationship between cultural engagement and crime has also been written about. It is argued that cultural participation allows for occupying time in constructive activities, improving skills and self-esteem and building healthy social relationships, leading to more pro-social behaviour and reducing the likelihood of offending (Taylor et al., 2015). Empirical studies are usually on cultural programmes applied to inmates, ex-offenders or populations at risk of committing crimes, and focus on rehabilitation and preventing recidivism.

By way of example, Keehan (2015) reviews a number of papers on the introduction of theatre practices in prisons and their potential to enhance the rehabilitation of offenders. Similar effects have been reported with music learning (Henley, 2015). Taylor et al. (2015), apply a systematic review of the literature on, among others, the relationship between arts and crime. They point out that studies often do not provide evidence on recidivism rates, as well as the need to fill a gap regarding the effects on offending at the community level, beyond the individual.

At the aggregate level, Azevedo (2016) studies the effects on crime of the European Capital of Culture in Guimarães (Portugal) in 2012. She sought to demonstrate that, through this event, the generation of a substratum of community cultural values and collective expression contributed to informal education processes that would result in more pro-social behaviour. She notes that there is indeed an effect but only on so-called ‘crimes against patrimony’. These include crimes against property, fraud, and crimes against cultural identity and personal integrity (i.e., discrimination on the basis of origin, ethnicity or religion). In contrast, she reports no effect on “crimes against persons” and “crimes against life in society.” She attributes this to the fact that the former are those crimes most closely linked to the previously mentioned informal education processes.

Environmental sustainability

References to environmental sustainability could not be missing either. The potential of cultural activities has also been pointed out with regard to greater environmental awareness and more committed behaviour towards the care and sustainability of the environment (Crociata et al., 2015; Burke et al., 2018). Li et al. (2022), assessing a pilot policy in Chinese cities, show that higher cultural consumption reduces SO2 emissions and particulate matter (PM2.5). Quaglione et al. (2017), Quaglione et al. (2019) point to the positive effect of cultural participation on energy savings and sustainable mobility patterns, respectively. Both on concern and on actually turning it into behavioural changes. However, they note that the effect changes depending on the type of cultural activity. Indeed, attending opera and classical music concerts is negatively associated with energy savings, while visiting heritage sites, reading books or newspapers has the opposite effect (Quaglione et al., 2017). Besides, Stanojev and Gustafsson (2021) point out that the incorporation of culture, and particularly cultural heritage, in smart specialisation strategies for the circular economy in European regions still remains underdeveloped, despite its enormous potential.

The evidence on the effects of culture on wellbeing is, as shown, abundant and increasingly solid. Yet, the studies seen so far discuss the impacts of culture in a general sense. Mainly, of different forms of cultural participation. They do not focus on the effects of CCI as part of the productive structure of a territory. Both approaches are logically closely related, given that cultural participation and consumption are generally a result of the goods and services generated by CCI, albeit with the not negligible exception of amateur cultural production. But transferring findings may not necessarily be automatic. Thus, the following section will focus on the evidence to date on the effects of CCI in particular.

Getting more concrete: impacts of CCI on wellbeing

Studies on the effects of CCI have mainly focused on the economic perspective. Evidence on their impacts on other dimensions of wellbeing therefore remains largely unexplored territory, with some exceptions noted below.

Material conditions

On the economic front, several reports over the last two decades have pointed to their growing importance in terms of employment, value added or turnover, as well as their high capacity for productivity growth and job creation, with higher rates than many other industries (e.g., KEA European Affairs, 2006; Power, 2011; Bakhshi et al., 2013; UNESCO, 2015). Their greater dynamism and resilience in the face of economic downturns has also been noted (Fontainha and Lazzaro, 2019).

But more relevant than their direct contributions is the role they play in the economy as a whole and how they affect other industries. Bakhshi et al. (2008), using input-output and econometric analysis, found that CCI were much more innovation-prone than other sectors. Therefore, they considered that they were not just another part of the production structure but an essential part of the whole system, generating innovation beyond their own sector. Olko (2017) comes to a similar conclusion. Based on a qualitative case study, he argues that CCI play a horizontal role in regional economies, impacting all other sectors and promoting smart regional specialisations. The extent to which this translates into economic growth has been the subject of a handful of studies in recent years.

Boix-Domènech and Rausell-Köster. (2018) review the literature to date on the effects of CCI on economic growth in the European Union. Among the studies collected there is evidence of the impact of CCI on GDP per capita (Rausell-Köster et al., 2011; De-Miguel-Molina et al., 2012; Boix-Domènech et al., 2013; Marco-Serrano et al., 2014), labour productivity (Marco-Serrano et al., 2014; Boix-Domènech and Peiró-Palomino, 2017; Boix-Domenech and Soler-Marco, 2017), total factor productivity (Hong et al., 2014), per capita disposable household income (Marco-Serrano et al., 2014) or the hourly wage in non-creative activities (Lee, 2014). Outside Europe, evidence of the impact of CCI on income can also be found in the USA (Dolfman et al., 2007) and in Australia (Potts and Cunningham, 2008).

The first generation of these studies find that CCI play a determining role in the wealth of a region (e.g., De-Miguel-Molina et al., 2012). Boix et al. (2013) even point out that the effect of CCI is larger than the overall effect of knowledge-intensive services. However, the early work was too optimistic about the size of the effect. Boix-Domenech and Soler-Marco (2017) moderate the results of the CCI on productivity from previous studies with a better specification of the model grounded on the endogenous growth literature, after controlling for a number of elements not considered in previous studies (especially in relation to the capital stock). Even so, they find that the effects on productivity are as important as those of scientific research or highly qualified human capital. Most of the productivity effects are indirect: that is, not because these sectors are themselves more productive, but because they improve the productivity of other sectors. In short, they determine a region’s capacity to innovate. Moreover, it is noted that CCI generate indirect spillover effects also on neighbouring regions.

The isolation of the causal effect between CCI and income, and the direction of this effect, is usually called into question. This has been conveniently addressed by Rausell-Köster et al. (2011) and Marco-Serrano et al. (2014), who find a circular causal relationship between CCI employment and economic growth. Not only do CCI cause higher income, but also wealthier regions tend to have more CCI: their citizens demand more cultural goods and services (on the demand side), and in turn more cultural capital is accumulated through education, as well as more cultural infrastructures (on the supply side), among other factors. A virtuous circle is thus formed, fuelled by CCI. The authors find that the effect of CCI on economic growth is more immediate than the reverse. It is also noted that two factors are essential for the proliferation of CCI, namely, urban centres and higher education.

Subsequent studies have confirmed these positive results, with increasingly sophisticated and well-established models. Innocenti and Lazzeretti (2019) qualify that, in order to generate growth, CCI must be accompanied by other sectors with a high degree of proximity or relationship. In other words, sectors that can benefit from the generation of ideas and creativity. CCI do not necessarily generate growth on their own but by contact with these sectors through cross-fertilisation. It is not the mere concentration of CCI but the ability to exchange knowledge and ideas with other related sectors that makes the economy prosper. There are in fact some CCI that are more related to external sectors than to other CCI, such as architecture or design. This does not mean that they are less creative but that they are more likely to exploit their creativity in other non-creative industries.

In a similar vein, Rodríguez-Pose and Lee (2020) find evidence that the presence of both scientific and creative activities, and their complementarity, are essential for innovation in cities, but not separately. The authors show that, while scientific activities have a greater impact, they do not achieve this on their own but need the creative component. A similar conclusion is reached by Zhao et al. (2020) with the positive interaction between creative workers and ICT workers leading to higher Gross Value Added (GVA) growth. Also Santoro et al. (2020) show that collaboration (formal or informal) of CCI with other sectors enhances innovation performance.

Another interesting approach is that developed by Boix et al. (2022). They again adopt a semi-endogenous growth model and apply it to three samples of different territorial levels: countries, regions and municipalities. Positive causal effects on GDP per capita are confirmed. Although the effects may be heterogeneous between territories. Boix et al. (2021) point out that, although the overall effect on regional productivity is positive, there are a few regions where it is not, depending on a number of enabling factors.

The impact of the widely differing activities included in the broad concept of CCI is also expected to be heterogeneous, although the availability of data does not always allow this to be verified. One of the few forays in this direction is the input-output analysis conducted by Lyons (2022) in the Cardiff City-Region. It distinguishes between nine sub-sectors and observes notable differences in GVA per Full-Time Equivalent worker. The highest in design and the lowest in heritage-related activities (museums, galleries and libraries). Nevertheless, the different CCI have significant co-location patterns, i.e., correlations between the presence of one creative activity and another (Boix-Domènech et al., 2013; Boix-Domènech et al., 2015), and mutually benefit from this spatial co-location. Thus, especially in the absence of more disaggregated data, it makes sense to consider these industries grouped together as a whole. Indeed, as mentioned, Dellisanti (2023), while distinguishing between inventive and replicative CCI, finds positive effects on GDP growth from both. However, there is also evidence that the impacts of creative manufacturing on productivity (Boix-Domenech and Soler-Marco, 2017) and GDP per capita (Boix et al., 2021) are not as positive as those of creative services. But manufacturing is often neglected when analysing CCI since it is not considered to be a major creator of symbolic content.

As regards employment, papers merely pointing out the size and growth trends of CCI usually note their job-creating capacity. However, research on the possible effects on the labour market beyond employment in CCI (i.e., on the overall level of employment or unemployment in a territory) is slightly scarcer. On the one hand, Gutiérrez-Posada et al. (2022) find that, in UK cities, for every job in CCI, almost two (1.96) additional jobs are generated outside them. On the other hand, the aforementioned input-output analysis performed by Lyons (2022) in the Cardiff City-Region also includes multiplier effects on employment, considering direct, indirect and induced effects. However, the results of Maddah and Arauzo-Carod (2025) for municipalities in Catalonia suggest that employment growth driven by CCI occurs only in rural areas.

As stated at the outset, the link between CCI and income has been the most investigated, but many other dimensions of wellbeing remain largely unexplored. As Dellisanti (2023) argues, once the economic growth effect of CCI has been demonstrated, further exploration should be made of the social impacts that are produced through the cultural component. Although research in this area is scarcer, some pioneering incursions can be found. All of them are very recent, which is an indication of the hotness and interest of the issue.

Acquiring knowledge

A positive causal link has also recently been found between the level of employment in CCI and the level of education in a region (Berti Mecocci et al., 2022). Taking a mainly supply-side approach, the authors consider several ways in which this phenomenon occurs, including that CCI require creative professionals, generally highly qualified, and therefore provide an incentive to pursue these levels of studies. It could also be considered that offering greater opportunities for the professional development of creative and artistic profiles allows students skilled in these subjects to have greater motivation to continue their studies and possibilities to study what they really like and feel valued in, and thus avoid failure, frustration and dropping out of school.

Subjective wellbeing

Regarding subjective wellbeing, Fujiwara and Lawton (2016) tested whether happiness and life satisfaction were higher in creative occupations, focusing on the workers themselves. The results were mixed, being higher for some occupations but lower for others. The precariousness associated with some jobs or the frustration accentuated by the greater identification with the work product (a characteristic feature of these activities) could be some of the causes that may explain the latter.

Environmental sustainability

Finally, despite the growing emergence of the issue, environmental sustainability is still largely unexplored in the field of CCI. One of the few works is the qualitative study by Gerlitz and Prause (2021). They conclude that cross-sectoral cooperation involving CCI activates the innovative capacity of SMEs in a way that enables them to adapt and make the sustainable transition whilst reducing their environmental impact. More recently, Rausell-Köster et al. (2025) have made a quantitative foray focusing on the impacts of CCI on air pollution. They report generally positive results, although with important differences between European regions.

Under-researched fields: long and healthy life and living in community

Finally, it should be noted that hardly any specific studies have been found on the effects of CCI on health or their social and community impacts, despite these being well-studied areas in terms of the effects of culture in general and certain cultural practices, revealing a significant gap. Among the scarce examples, mention could be made of Kalfas et al. (2024) who, through questionnaires to CCI stakeholders in Greece, find that CCI contribute to regional development not only in economic terms, but also in aspects related to social cohesion, cultural identity, urban regeneration or the revitalisation of declining areas.

To recapitulate, it has been found that, while studies linking various cultural practices to multiple dimensions of wellbeing are abundant, work on the impacts of CCI is mostly concentrated on economic growth and has so far left significant gaps in other areas of wellbeing. It is only in recent years that some other dimensions have begun to be explored. In most cases, however, these are partial analyses that do not pretend to encompass wellbeing from a holistic understanding. A separate mention should be made of Sanjuán (2025), who carries out a joint study of the impacts of CCICCI on the indicators of the OECD Better Life Index, thus covering all the domains of wellbeing that have been discussed. Using machine learning algorithms for causal inference, he finds positive impacts in eleven dimensions (access to services, civic engagement, community, education, environment, health, housing, income, jobs, life satisfaction and safety), but not without a high degree of regional heterogeneity.

Table 1 summarises some of the most relevant and recent empirical contributions covering each of the wellbeing domains stated in the introduction. Either the impacts of culture in general (mainly cultural participation and consumption), or specifically the impacts of CCICCI. It should be noted that some studies focus only on some specific cultural activities, are applied in a very specific context, or have other specificities (e.g., Fujiwara and Lawton (2016) only consider the satisfaction of creative workers, not the whole population). Points made in the previous paragraph are clearly reflected in the table, since the impacts on some dimensions have barely been investigated yet. Partly because they are usually seen as effects that derive from economic growth, without considering that CCICCI may have any other differential effect on them.

TABLE 1

Gathering evidence of the impacts of culture and CCI on different pillars of wellbeing.

Source: Own elaboration.

Discussion: drawing up a comprehensive analytical framework

On the basis of the theoretical background and the empirical evidence reviewed, it is now time to outline a comprehensive approach to explain how CCI affect wellbeing. An attempt is thereafter made to unify the relationships that have emerged into a theoretical framework capable of explaining all of them in a coherent and holistic manner. After that, however, we will dedicate a brief section to qualify some of the possible counter-effects of CCI, to avoid falling into the fallacy of considering them a miraculous solution to all problems.

Identifying impact transmission pathways

Elaborating a unified framework to explain how CCIs relate to wellbeing is not an easy task, as it involves two concepts that are already extraordinarily complex on their own. CCIs bring together a multitude of heterogeneous activities with very different effects. Whereas wellbeing involves dimensions that are also very complex and interconnected. If all the possible effects that each CCI can have on each dimension of wellbeing are considered, and how any single change then has repercussions on other dimensions of wellbeing and on some of the CCIs, the result is an unfathomable map of relationships expressed in very different ways. For example, architecture and urban design can improve the quality of public spaces, accessibility and sustainability, while cinema can entertain us, move us and convey values, heritage can reinforce our sense of community and collective identity, and fashion and design can express our personal identity.

But such a complete scheme of relationships would be completely unravelling and would not allow us to identify and explain the chains of transmission of these effects. As Jorge Luis Borges shrewdly ironised, a full-scale map is of no use, no matter how detailed it is. A certain level of abstraction must therefore be acquired and patterns must be sought that allow us to classify the main effects in a single general framework.

It is worth starting from the very nature of the CCI. That is, activities generating cultural goods and products (with a strong symbolic value content) through processes involving human creativity. Therefore, the process of creating and producing these goods is the primary role of CCI. The effects will be brought either in the creative production process or at a later stage through consumption or cultural participation of the previously produced cultural outputs. It is acknowledged that this process is rather more complex. This is a simplification for representative purposes. Indeed, UNESCO (1986), UNESCO (2009) identifies five phases in what they call the cultural cycle. It consists of creation, production, dissemination, exhibition/reception/transmission and consumption/participation, related in a cyclical model. Transferring it to the approach of this paper (if some simplification is allowed), the first three would be included in the first phase of production and the last two in the second phase of consumption or participation.

Three phenomena occur within these two phases. First of all, a production and consumption that are intensive in symbolic content are undertaken. Secondly, this is carried out through processes of creativity, idea generation and experimentation. And third, cultural uptake takes place through the consumption of the cultural goods and services generated. This third phenomenon therefore occurs primarily in the second phase (consumption/participation). The other two, on the other hand, take place in both the production and consumption phases. As for the intensity of symbolic content, because it refers to both production and consumption, which are two sides of the same phenomenon. And as for the creative process, this occurs naturally during production, but it can also bring out ideas as a result of this process, in the phase of participation and consumption.

These three phenomena give rise to four lines or types of effects. On the one hand, production and consumption centred on symbolic and experiential value would potentially lead to a less intensive exploitation of material resources compared to other economic activities that rely on a high consumption of physical and tangible inputs. This could contribute to the dematerialisation of the economy, both in production and consumption. The ecological sustainability of the production system would therefore be enhanced, as opposed to others that are more based on material values.

On the other hand, cultural uptake generates two types of effects. The experience of cultural participation itself, and the transmission of messages and meanings. The former generates a series of impacts on the participants or consumers of cultural goods and services. Rausell-Köster and Ghirardi (2021) categorise them into four: cognitive, emotional, aesthetic and social impacts. Cognitive impacts include everything that is learned from cultural experience. For example, we watch a film inspired by a historical event in which we discover facts we were unaware of, or we rethink our view on a topic. Emotional impacts involve everything that the cultural experience has made us feel: from pleasure, amusement, sadness, fear, excitement, etc. Aesthetic impacts concern the sensory perception of artistic expression: the pleasure of contemplating the beauty of a monument, or a painting that puzzles us, or listening to a song that evokes memories. Although these are also emotional impacts, some psychologists argue that aesthetic emotions are a different type from the other emotions of everyday life (Juslin, 2013). Lastly, social impacts occur as cultural practices usually involve social interaction as well as the expression of collective identities. Azevedo (2016) proposes a theoretical model that explains the transformation of individual cultural experiences through a chain of propagations until community-level social impacts are achieved. It starts from an enlarged capacity for empathy, and continues promoting social connections, expressing communal meanings, building a sense of community, developing social capital, empowering capacity for collective action, and finally achieving community revitalisation.

In turn, the messages can be internalised and incorporated into the individual and collective imaginary. These can be quite varied. One only needs to think of the variety of typologies and themes that museums, books, music or films address. But they may include promotion of critical thinking, acceptance of diversity, sense of belonging to the community, self-acceptance, identity building, knowledge transfer, preservation of collective memory, etc.

Finally, processes of individual and collective creativity, experimentation and the generation of new ideas foster innovation throughout the economy and society. This is in line with the ‘innovation model’ or ‘evolutionary model’ proposed by Potts and Cunningham (2008) and Potts (2009), which also has empirical evidence supporting this thesis (Boix-Domenech and Soler-Marco, 2017; Boix et al., 2022). Innovation driven by CCI is not necessarily only of economic applicability and market-oriented. It can permeate the whole of society beyond the productive structure (Gustafsson and Lazzaro, 2021). Innovation can also be social (original interventions to address social issues), political (applying novel public action responses) or urban (through the redefinition of public spaces and their uses), to name a few. Innovation should be understood as the ability to adapt to the changing reality, but also as the ability to proactively transform this reality. Ultimately, it strengthens resilience. To square the circle, four types of effects are derived as a result of three phenomena during two phases of one single process.

These impact-generating vectors logically affect the different components of wellbeing. But for this to happen, they must trigger changes that will depend on the existence of a set of enabling factors (e.g., supportive institutions, a strong associative network, or complementary economic sectors) (Bonet and Calvano, 2023). These are what allow an innovative idea to materialise, or experiences and messages to trigger changes in people’s behaviour. In other words, that the activity of the CCI has resonance. For the sake of simplicity and because it is beyond the scope of this paper, these enabling factors will not be further elaborated. But it should be borne in mind that they play their role, and that the expected effects of CCI are not always achieved if there are not a series of factors that allow them to materialise in real changes.

The assumption is that these effects have different positive impacts through which they enhance the components of wellbeing as defined above, i.e., on material conditions, on a long and healthy life, on acquiring knowledge, on living in community, on sustainability and on the subjective perception of wellbeing.

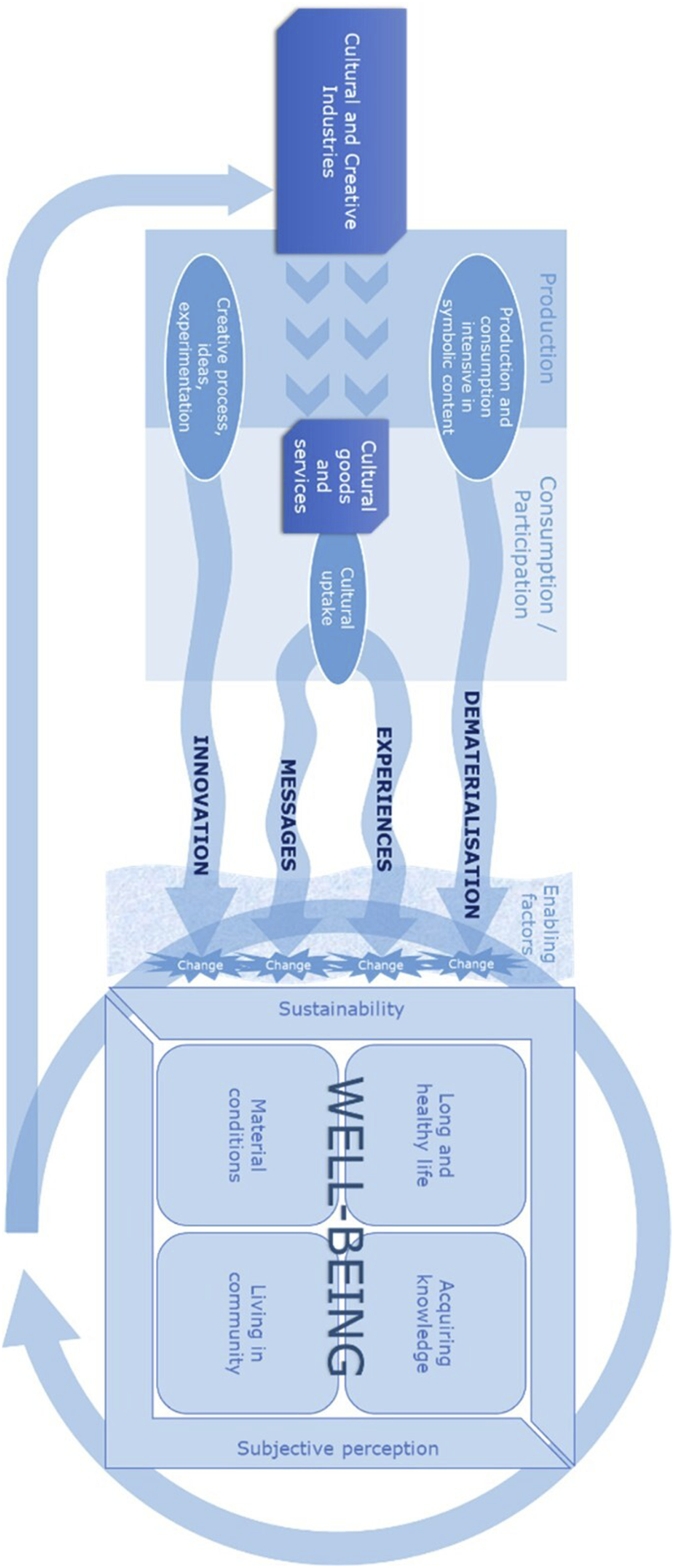

In turn, the different dimensions of wellbeing experience numerous and complex interactions with each other. This is not a linear and unidirectional relationship, but rather a feedback loop, as graphically depicted in Figure 1. On the one hand, the dimensions of wellbeing are interrelated. Education affects employment and income, this affects health and social relations, this affects life satisfaction, and so on. They are mutually reinforcing, so that an improvement in one of them can also lead to indirect improvements in other dimensions. These wellbeing improvements also logically affect the very enabling factors that allow the effects generated by CCI to translate into real changes (e.g., through a more cohesive society or stronger institutions).

FIGURE 1

Relationship diagram between CCI and wellbeing. Source: Own elaboration.

On the other hand, wellbeing also affects the possibilities for the development of CCI, feeding back into them. Higher education shapes creative workers (Comunian et al., 2015) and is, in turn, a key determinant for higher cultural participation as it facilitates decoding symbolic value (Suárez-Fernández et al., 2020) and thus higher demand for CCI; higher income also provides a boost in this direction (Marco-Serrano et al., 2014), etc. In short, the components of wellbeing, fuelled by the CCI, reinforce both themselves and the CCI. This is represented in Figure 1 as a double loop, from wellbeing to self and from wellbeing to CCI as a return arrow.

All in all, the underlying idea of this approach is that CCI can activate a wellbeing-generating process, in each of its aspects, which enters into a virtuous circle with the capacity for self-reinforcement. CCI would therefore be an economic activity with a high economic and social return in terms of wellbeing and, consequently, so would be the policies aimed at promoting them as a vector of specialisation.

Not all is rosy: possible counter-effects of CCI

Notwithstanding the above, we should not make the mistake of thinking that all the effects of CCI will be positive. Of course, CCI can also generate pernicious effects. Following the proposed scheme: not all CCI contribute to a less intensive use of material resources; cultural experiences may provoke discomfort; the messages and social meanings conveyed may be detrimental to wellbeing; and innovation may also have malicious applications, or provoke unintended adverse effects. The following are some examples that have been reported.

Starting with dematerialisation, in addition to the fact that not all industries that are part of CCI comply with this general principle, some may actually act in the opposite direction. Through design and advertising, for instance, fashions can render obsolete durable goods that are still perfectly usable but are no longer trendy. This reinforces consumerism and unsustainable resource use.

Moving on to the experiences, contemporary music concerts and festivals can be associated with excessive alcohol and drug use, thus with health hazards (Lim et al., 2010; Lai et al., 2013; Douglass et al., 2022).

In the same vein, spending too much time watching television or playing video game encourages sedentary lifestyles that are detrimental to health (Hu et al., 2003; Rey-López et al., 2008; Kohorst et al., 2018). This overexposure can also lead to social isolation (André et al., 2020).

The potential harmful effects are not only confined to consumers, but also to the producers themselves. Some CCI activities are characterised by an intense precariousness of employment and a predominance of multi-employment and freelance workers, with low and unstable incomes and low job security (Hesmondhalgh, 2010; Morgan et al., 2013; Pasikowska-Schnass, 2019; Comunian and England, 2020). The vocation, the need for self-fulfilment and creative expression that these activities provide is precisely what drives them to accept these conditions to the detriment of their material quality of life. To such an extent that this ‘bohemian’ lifestyle, full of uncertainty, comes to be considered consubstantial with artistic creation itself (Eikhof and Haunschild, 2006; 2007).

In addition to producers and consumers, cultural experiences can indirectly affect third parties. A clear example of a negative externality would be a concert hall disturbing the sleep of neighbours. Also, tourism attracted by CCI (heritage in particular, but also festivals or other cultural events) can be problematic if it leads to tourism over-concentration. On the one hand, tourism-related activities generally generate less value added and have lower than average labour productivities. This makes overly tourism-dependent economies fragile, volatile, with precarious employment and limited development potential. Not forgetting the environmental impact of international travel, for example, by plane or cruise ship (Brida and Zapata, 2010; Higgins-Desbiolles et al., 2019).

Along these lines, the attraction of large volumes of tourism, brought about by the cultural offer, can turn cities into barely liveable theme parks. Overtourism can cause disruption to the daily lives of local residents (Steiner et al., 2015), and even exclude them from enjoying the cultural heritage of the place. Particular attention has been paid to the gentrification dynamics that this provokes (Díaz-Parra and Jover, 2021; Jover and Díaz-Parra, 2022). Housing for permanent use, dragged down by more profitable tourist accommodation, becomes more expensive and pushes residents out to the suburbs (in turn causing longer commuting times, thus worsening urban mobility and air quality). This effect is not unique to tourism but occurs whenever a neighbourhood undergoes processes of change that attract a new, wealthier population to replace previous residents. It can also occur, for instance, with the attraction of the ‘creative class’ proposed by Florida (2002) or with culture-led urban renewal processes. The increasing centrality of art and culture within the urban economy has prompted much debate about their relationship to urban change, although its link to gentrification is not entirely clear (Mathews, 2010; Stern and Seifert, 2010; Gainza, 2017; Pratt, 2018). Yet this entails that artistic initiatives in run-down neighbourhoods are sometimes viewed with suspicion or outright hostility, despite fostering a more pleasant environment (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Graffiti reading ‘Your street art raises my rent’ on a mural by the artist Okuda in Madrid. Source: X post (formerly tweet) by @gustau_perez on 6 July 2019. https://x.com/gustau_perez/status/1147449064184864769/.

It is now the turn of messages and meanings conveyed by CCI, which are not always to the benefit of wellbeing. Take advertising as an example. Advertising can generate a state of permanent dissatisfaction by inducing new needs that were not there before (Michel et al., 2019). It can even lead to distortions in the perception of one’s own body due to the overexposure of idealised bodies (Lavine et al., 1999; Blond, 2008), as well as promote the consumption of unhealthy products (Boyland and Halford, 2013).

One criticism that arises in this sense is precisely the one pointed out by mass society theorists about capitalist ideological domination. The media, concentrated in most countries in the hands of a few business groups, have great power to condition public opinion and political debate to the benefit of the interests of a wealthy minority and to the detriment of the wellbeing of the social majority (Barnes and Hicks, 2018).

Besides, the content of books, audio-visual products or performing arts can sometimes promote narratives that instil hatred, that stigmatise and exclude certain groups or that perpetuate discriminatory social roles. For example, Jones (2011) exposes how the media, series and films have contributed to the ‘demonisation’ of the working class by fuelling stereotypes, thus contributing to social dismemberment. Another paradigmatic case is the gender roles and romantic love myths that are reinforced and perpetuated in classic animated films (Garlen and Sandlin, 2017), or the sexist messages that abound in the lyrics of some songs (Armstrong, 2001; Eze, 2020). Moreover, in the context of ‘Culture 3.0’ (Sacco et al., 2018) in which cultural production (especially audio-visual) is highly decentralised, the risk of spreading hate speech (e.g., through streaming platforms) becomes more significant.

Finally, the possible adverse effects of innovation will not be dwelt upon, as they extend far beyond the sphere of action of the CCI. CCI act as facilitators of innovation not only in their strict field but in many others apparently unrelated to culture and creativity. Although innovation is generally positive because it allows adapting to changing circumstances and moving forward, it is not difficult to think of examples of innovations that have had a negative impact on wellbeing. One very clear one is innovation in the field of military industry, or the invention of the atomic bomb in particular. But not only in terms of technical innovation. The strategy of manipulation and control of the masses devised by Joseph Goebbels as Minister of Propaganda of the Third Reich can be considered, at the time, a perverse case of political and social communication innovation. These are extreme cases of innovation deliberately applied for destructive purposes or to subjugate the population. But well-intentioned innovation can also have unintended detrimental effects. For example, the development of the automobile was intended to improve transportation, and it has indeed increased the possibilities for travel and shortened distances considerably. However, it has also been accompanied by deadly traffic accidents, loss of space for pedestrians or children’s play in cities, or an increase in emissions of gases that are harmful to the planet and to health. These effects were not intended, but were the result of innovation.

Nonetheless, the fact that culture may generate these or other problems does not mean that we should give up all that it brings: pleasure, identity, self-expression and so many other qualities that ultimately enhance wellbeing and make life worthwhile. On the contrary, policymakers should be aware of this and accompany the processes of cultural and creative development with public policies that avoid or mitigate these effects, while steering the processes towards socially desirable outcomes.

Let us illustrate this with the problem of gentrification. Gentrification harms the original neighbours by driving up housing prices and even driving them out. This definitely disrupts the social fabric of the place. But it does not mean that we should be resigned to letting the neighbourhood degrade. Policymakers should definitely not renounce regenerating spaces, providing them with green areas, cultural offerings, public services and, in short, making the neighbourhood more pleasant and improving the quality of life of the residents. But the improvement of neighbourhoods has to go hand in hand with the right of residents to stay (Pareja-Eastaway and Simó-Solsona, 2014). Or to put it another way, alleviating problems in one neighbourhood does not mean transferring those who suffer from them to continue suffering elsewhere, further away. To this end, urban regeneration policies must be accompanied by public housing policies, rent controls, regulation of tourist accommodation, etc. Similarly, the problems arising from advertising are combated with advertising regulation based on consumer protection. Likewise, campaigns to promote healthy habits and healthy eating can be carried out precisely through advertising. Just to cite a few examples.

All in all, if there is one thing that is absolutely clear, it is that the relationship between CCI and wellbeing is extremely complex. These are very diverse sectors that generate multiple effects on the economy, society and the environment. These effects can be both positive and negative. However, we must bear in mind that any analysis in aggregate terms, with a territorial level lens, requires abstraction to a certain extent in order to disentangle such complex and interconnected relationships.

Without seeking by any means to oversimplify reality or deny the existence of one or other impacts, the abundant empirical literature reporting positive effects of culture on different dimensions of wellbeing suggests that these are prevalent. Though it is possible that in some aspects they may not be. Or they may not be for all territories or in all circumstances.

Conclusion

This article has explored the contribution of Cultural and Creative Industries (CCI) to human wellbeing from a broad and multidimensional perspective. Far from limiting their value to purely economic returns, CCI have been shown to influence a wide array of aspects that shape people’s quality of life: from education and health to social ties, cultural expression, environmental awareness, and overall life satisfaction. Through creative processes, symbolic content and participatory experiences, these industries generate effects that often go beyond their immediate outputs, embedding themselves in social dynamics and territorial development.

As noted in the introduction, this paper aimed, first and foremost, to situate the state of the art regarding the relationship between CCI and wellbeing. As a result, it also sought to outline a theoretical framework of the main transmission chains of the impacts of CCI on wellbeing.

Regarding the first point, the effects have been structured into six pillars of wellbeing, considering material, social, health, education, subjective wellbeing, and sustainability factors. It has been found that, although studies on cultural relations are abundant–albeit usually from partial and localised perspectives– (especially in areas such as health, subjective wellbeing and community building), research on the effects of CCI in particular, and from a more macro perspective, has mainly focused on their economic impact, with significant gaps remaining in other areas (refer back to Table 1). This mismatch between the abundant micro evidence of certain cultural activities in the overall dimensions of wellbeing, which points to the probable existence of macro effects generated by stronger CCI ecosystems in the places where they are located, and the absence of research in this latter area, suggests that such research is needed.

As for the second purpose of this paper, building on the recent theoretical debates and empirical findings previously discussed, a comprehensive analytical framework has been formulated in order to articulate a holistic understanding of how CCI can act as drivers of collective wellbeing. This framework considers the different vectors of transmission of CCI impacts, which would eventually be capable of activating a virtuous circle of wellbeing enhancement (refer back to Figure 1).

Yet, bringing together the wide range of activities that make up the CCI, with their very different specificities, into a single unifying framework, while intended to be useful for general analysis, is at the same time one of the main limitations of this paper. The relationship is, of course, much more complex. Specific cultural activities may generate particular effects, in certain dimensions, on certain segments of the population and in certain circumstances. Attempting to explain all of them exceeds the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, it is considered that the general framework, although inevitably involving a certain degree of simplification and loss of detail, can be a useful starting point for analysing the general link between CCI, conceived as a network of activities with certain common features that make up the cultural and creative ecosystem, and wellbeing. From a public policy perspective, these findings offer important implications. In the European context, where both cultural diversity and regional disparities are significant, the potential of CCI as levers for inclusive and sustainable development should be more fully harnessed. This requires moving beyond a narrow economic framing and recognising the multidimensional contributions of CCI to societal wellbeing. It also calls for integrated policy frameworks that link culture with education, health, social cohesion, and green and digital transition strategies. Moreover, it is essential to ensure that policies aimed at promoting CCI do not exacerbate inequalities, but rather enable broader access to the benefits they generate and empower communities across different territories. From the perspective of academic research in cultural policy and management, while the evidence on the economic impact of CCI is relatively well established and appears to be sufficiently proven, there remains a notable scarcity of robust empirical research into their effects on wellbeing in a comprehensive sense. Much of the available work is fragmented or focused on specific activities, dimensions or contexts. In some instances, in the absence of rigorous studies with sufficiently robust evidence, reliance is placed on grey literature, which has been criticised as overstating results (Clift et al., 2021).

Future research should aim to address this gap by adopting more holistic analytical frameworks, causal inference models and territorial disaggregation, in order to better understand the conditions under which CCI can most effectively enhance wellbeing. In short, there is a clear need for further empirical investigation to capture the full scope and complexity of this relationship.

Statements

Author contributions

JS has devised the research, reviewed the literature, analysed it, made the theoretical contributions and written the paper.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Article Processing Charge for publication has been funded by ENCATC for being a finalist for the ENCATC Research Award 2024. This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Universities through the “Formación de Profesorado Universitario” Programme [FPU19/00182].

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on and results from the research process followed during the author’s doctoral thesis, which is accessible in an open repository (Sanjuán, 2023).

Conflict of interest