Abstract

Cultural centers play a crucial role in European sociocultural life, yet remain under-researched as their diverse nature has hindered consistent analysis and policymaking. A key challenge is the absence of a clear definition, leading to inconsistent categorization and making it difficult to assess their visibility in statistics, funding allocations, and cultural policy frameworks. This gap limits researchers, communities, and policymakers from fully understanding and supporting these institutions. Without clear definitions and standardized data collection, cultural centers struggle to secure funding, and underserved communities risk losing access to vital cultural and social resources. This is crucial, especially for rural and sparsely populated areas, where cultural centers often serve as key cultural infrastructure that supports social cohesion, cultural participation, and regional equity. To address this gap, this study develops a structured framework to define and classify cultural centers, aiming to enhance conceptual clarity and support evidence-based policymaking. Focusing on Finland as a case study, this study employs the Walker and Avant concept analysis method to identify four defining attributes of the concept cultural center: provider and creator, experience and active participation, diversity and multidisciplinary, and interaction and community orientation. Through a systematic and descriptive approach, these attributes are operationalized and applied to a dataset from Statistics Finland on Cultural halls and centers by region 2023, which reflects the current landscape of cultural centers in Finland. By systematically examining 259 facilities, the study traces the presence of these attributes in practice. The combination of conceptual analysis and empirical investigation results in a refined typology that allows for a clearer distinction between cultural centers and other facilities. This structured approach not only advances theoretical clarity but also supports cultural policymakers in recognizing and categorizing cultural centers more effectively. The findings emphasize the need for improved data collection to better capture the diversity and roles of cultural centers, both in Finland and beyond. Although this research focuses on Finland, the developed typology may offer a useful framework for cross-country comparisons and could support policy alignment within the EU cultural sector, provided that local adaptations are made.

Introduction

Cultural centers play a central role in the artistic and sociocultural life of European communities, both large and small (Peeters, 2017: 17). However, operating under various names and organizational structures (ENCC, 2023), they remain somewhat ambiguous due to the lack of a clear definition and differentiation (Järvinen, 2021b: 9). This ambiguity contributes to the limited understanding of their impact, even though Europe is home to thousands of cultural centers (Eriksson et al., 2017: 5). Therefore, this article brings important insights regarding this under-researched area by pointing to the richness of their offerings and the diversity of their organizational forms and activities.

One of the few exceptions are the so-called socio-cultural centers, whose essence (e.g., Dallmann, 2015; Kegler, 2020; Kegler, 2023) has been expanded upon by researchers, especially in Germany, with a 50-year tradition of socioculture (Sievers, 2023). Beyond this, the available research rarely prioritizes conceptual clarity, particularly regarding the term ‘cultural center’. As a result, ‘cultural center’ and ‘socio-cultural center’ are often used interchangeably (e.g., Eriksson et al., 2017; Ranczakowska et al., 2024). However unlike more clearly defined cultural organizations such as museums, libraries, theaters, concert halls, and galleries, where specific activities and functions are readily identifiable, cultural centers encompass a broad and varied range of activities. This diversity makes it a dynamic concept, which resists confinement to a single, enduring definition (Kegler, 2020: 29) and thus aggravating classifying and developing a typology for cultural centers (Pfeifere, 2022: 29). Recent attempts of clarification have been made by Stenlund (2010), Ruusuvirta and Pasi (2014), Dapkus and Dapkutė (2013), Eriksson et al. (2017), Bogen (2018), Järvinen (2019); Järvinen (2021a), Pfeifere (2022), as well as ENCC (2023), presenting a wide range from short and functional definitions to the attempt of presenting a lengthy one-fits-all-definition. This research stands on these shoulders as it delivers a new and unique typology that differentiates between the various facilities operating under the label ‘cultural center.’ This refined classification provides a structured framework for distinguishing cultural facilities, addressing the conceptual ambiguities that have hindered previous research. By offering a more precise categorization, this typology enables cultural policymakers, researchers, and practitioners to better understand, support, and develop cultural centers. Moreover, it facilitates more targeted policy interventions and funding decisions that recognize the distinct roles and contributions of different types of cultural centers to their municipalities.

Today’s landscape of cultural centers in Finland is partly reflected in a dataset from Statistics Finland (Statistics Finland, 2023). This dataset on Cultural halls and centers by region 2023 does not paint a realistic picture due to its rather informal data gathering process and unclear conceptual foundation. According to Statistics Finland, this dataset is not intended to comprehensively cover every cultural house in Finland but aims to provide as detailed an overview as the available resources allow, given the broad and loosely defined nature of ‘culture house’ in the Finnish context (Pitkänen, 2023). So far, their data gathering process includes a two-step verification: checking the existing entries of the dataset for activity online, followed by a search for new establishments using the terms culture center and culture house, along with the names of all Finnish municipalities. With each update, the table is revised to ensure it contains the most current information, replacing outdated data (ibid). The outcome of these procedures can also hardly be called a statistic, as it currently stands, it is more like a long list than a table of data (Pitkänen, 2024). A comparison of this dataset with institutions discussed in recent literature on cultural centers in Finland (e.g., Järvinen, 2019; Järvinen, 2021a) reveals that this method overlooks institutions that do not explicitly include the word culture in their title, thereby perpetuating conceptual ambiguity. However, it is precisely this combination of ample data resources and conceptual vagueness surrounding cultural centers that makes Finland a methodologically rich environment for analysis and a theoretically important context for refining the understanding of what constitutes a cultural center. In addition to its specific policy and data context. Finland offers an analytically productive setting for conceptual exploration due to the transparency of its institutional landscape. The relatively limited number of institutions labeled as cultural centers provides a coherent case for developing and testing a typology, which may later be transferred to or adapted for more complex cultural contexts. As a Nordic welfare state with a strong municipal role in cultural provision, Finland also represents a governance model that balances state-led and community-based approaches to cultural infrastructure. In this sense, Finland does not merely serve as a convenient empirical setting, but as a structured and transferable policy context that allows for conceptual testing with potential relevance beyond national borders.

This study fills a research gap by defining the concept of a

cultural centerand developing measurable indicators to identify it in practice. Using the example of Finland, it aims to clarify and categorize the facilities that so far all operate under that name, applying a methodological approach that combines qualitative conceptual analysis with descriptive statistical analysis. The empirical findings were deliberately designed to be descriptive in order to systematically explore a field that has received little research attention to date. The research questions focus on defining the concept of

cultural centersand distinguishing between different facilities operating under this name:

1. What is the essence of the concept cultural center?

2. What aspects differentiate cultural centers from other cultural facilities?

3. How can the different facilities operating under the name ‘cultural center’ be traced in practice?

This research is timely, as Finland’s cultural funding (Kulttuuriministeriö, 2024) and the scope of statistical data collection (Karttunen, 2024) face potential cuts, which would undermine cultural research and leave Finland as the only Nordic country without a systematic cultural data infrastructure (Jaakkola, 2024). Rather than justifying these reductions, it is crucial to strengthen data collection and evaluation methods to support cultural centers as key pillars of civil society and cultural policy.

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of cultural centers. Chapter two outlines the origin of cultural centers in Europe and Finland, while Chapter three discusses prevailing definitions of culture and cultural centers. Chapter four explains the methods and data the study relies on. Chapter five applies concept analysis to examine the structure and function of cultural centers, identifying key attributes and developing a tool to differentiate various forms and locations. In doing so, it responds to research questions 1 and 2. Chapter six responds to research question 3 by showing how this tool is applied in practice. It uses data from Statistics Finland to classify and review cultural centers in Finland, employing descriptive statistics and categorical data analysis to provide insights into their distribution and characteristics. Chapter seven discusses methodological concerns and the relevance of the findings.

Cultural centers in Europe: historical trajectories and the Finnish perspective

Cultural centers have been shaped by historical, political, and socio-economic processes, which have influenced their development and current state (Bogen, 2018: 12). Following World War II, the rise of the welfare state in Europe led to increased public funding for culture and the establishment of cultural centers by the state. However, different countries adopted varying approaches to cultural provision, with some relying more heavily on state-run systems and others having a stronger presence of civil society. Up to today, this has resulted in fewer non-governmental centers in countries with a more state-run approach like Finland (Järvinen, 2021b: 2). Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Eastern Bloc countries struggled to develop effective cultural policies that balanced national identity and the evolving societal needs (Dapkus and Dapkutė, 2013: 96). In response, countries like Lithuania, Latvia, and Bulgaria implemented legal measures to enhance cultural access and promote civil society (Pfeifere, 2022: 34). Lithuania was particularly proactive, enacting the Law on Centers for Culture in 2004 to create a structured network of cultural centers. This law defined their scope, financial norms, and legal regulations, improving their efficiency, autonomy, resources, and role in the cultural landscape (Dapkus and Dapkutė, 2013: 98).

In many Western European countries on the other hand, many private cultural centers were established in the 1970s and 1980s, emerging from the civil society cultural initiatives of the 1960s (Järvinen, 2021b: 2). These initiatives were characterized by democratization debates and in some places, such as Germany, resulted in exploratory movements that sought new content and formats in the discussions on educational and cultural policy reform (Sievers, 2023: 35). Following the initially theory-driven uprising of the social protest movements of the 1960s, the subsequent generation developed a desire not only to fundamentally criticize the social conditions they perceived as entrenched and alienating and to demand their radical transformation, but also to initiate practical changes within their own sphere of influence. They aimed to start on a small scale, to dismantle hierarchies, to redefine gender roles, to replace private property with collective forms, and to prioritize self-determination over alienated labor (Dallmann, 2015: 10). The explorations related to cultural practices as well as urban development towards a more humane city that enables the social, intellectual, and cultural development of individuals (Eichler and Knoblich, 2023: 38). This practical engagement with social and cultural experimentation paved the way for the coining of the concept of socioculture, which has since had a particularly significant impact in Germany, where it can now look back on an efficacious 50-year history (Sievers, 2023: 35f). The authors Glaser and Stahl defined it in 1974 mainly as an attempt to understand art as a medium of communication, among other things as an essential means of bringing together a society fragmented by individual interests, conflicts of interest and communication barriers on a communicative level. The prefix socio indicated both the alternative and the complementary aspects. It also heralded the maximum opening of culture into social space. In this context, sociocultural centers can also be understood as early manifestations of what Oldenburg (1999) later theorized as Third Places (Bangert, 2020: 374), accessible spaces beyond home and work that foster informal social interaction, community cohesion, and democratic engagement. These centers provided structured yet open environments that enabled diverse social groups to connect, deliberate, and participate in cultural and civic life. This linguistic overcoming of the separation between the art world and social reality was reflected in a multitude of new cultural institutions and formats, from cultural stores and workshops, adult cultural education institutions, music and art colleges, to youth and street theaters and much more (Sievers, 2023: 36).

In Finland, the cultural debates during the 1960s brought attention to the activities, needs, and cultural perceptions of citizens, but were also related to changing urban structure with more places for culture and cultural events in residential areas in the suburbs. The focus shifted from supporting artists to addressing the audiences, leading to the introduction of the concept of cultural democratization (Silvanto et al., 2008: 8). This concept, spurred by insights from French culture researcher Augustin Girard, emphasized making culture accessible to everyone, regardless of their background, and encouraged active participation in cultural creation (Skot-Hansen, 2005: 33). Cultural democratization also stressed the value of diverse cultural expressions and aimed to affirm the identity and self-worth of various groups through cultural engagement. Additionally, the significance of arts education began to gain recognition during this period (Silvanto et al., 2008: 6). This approach sought to level the cultural playing field, allowing different social groups such as women, workers, gays, and ethnic minorities to express their cultures within the frameworks provided by municipalities. The changes were marked by significant legislative actions like the Promotion of the Arts Bill and the Artists’ Grants Act in 1967, which blurred the lines between high and popular culture (Kangas, 2003: 84f), helping to open the cultural sector to society and overcoming a primarily reception-based concept of culture. This transformation included redefining cultural facilities to prioritize communication, create free spaces, and encourage reflection. A crucial aspect of implementing this vision in Finnish society was the establishment of arts facilities within residential neighborhoods (Silvanto et al., 2005: 171). While facilities with similar cultural functions existed previously in Finland, they were not specifically recognized as cultural centers (Järvinen, 2021b: 2). The concept of multipurpose cultural centers evolved from the legacy of community halls and youth associations, which served various functions. Despite this, their prominence was diminishing, and they had not significantly expanded their reach into wider areas (Silvanto et al., 2005: 171). In 1972, the city of Helsinki, driven by cultural policy debates and urban planning concerns, commissioned a study to assess the feasibility of establishing new multi-purpose centers across the city. The motivation stemmed from the quality-of-life issues faced by residents newly relocated to the suburbs, who lacked cultural activities and services (Silvanto et al., 2008: 8). The study highlighted the benefits of such centers, including economic advantages and the consolidation of diverse activities in a single space, fostering social interactions and empowerment among different social groups. The proposed centers aimed to house varied activities to attract and unify groups of different ages, social backgrounds, and interests, and to break down barriers between different art forms without the need for expensive, specialized venues in the city center. The concept emphasized activation and community benefits derived from engaged and empowered individuals (ibid: 10). As a result of this study, three centers were created with Stoa (est. 1984), Kanneltalo (est. 1992), and Malmitalo (est. 1994), which attracted nationwide attention and set precedents for multipurpose community centers in the country (Silvanto et al., 2005: 168). Particularly, Stoa, as the first of its kind in Finland, served as a model for many other cultural centers that were built in the following decades in various parts of Finland (Silvanto et al., 2008: 12).

The definition problem

Today cultural centers seem somewhat self-explanatory, yet they remain enigmatic due to the lack of a clear definition and differentiation (Järvinen, 2021b: 9). They exist in various forms and do not have a universally agreed-upon name. In Finland, with its two national languages, they are, among others, usually referred to as kulttuurikeskus, kulttuuritalo, as well as kulturhus, kulturcenter, or konsthus. Defining the concept of a cultural center poses significant challenges mainly for two reasons: their diverse nature, encompassing various programs, missions, objectives, governance models, and resource availability, and the complexity of the underlying concept of culture.

Culture is a difficult concept: it is widely accepted and therefore seemingly familiar, but in academic research hard to handle (Soini, Kivitalo and Kangas, 2012: 2). It is considered one of the two or three most complicated words in the English language (Bogen, 2018: 8). Already in 1952, American anthropologists Kroeber and Kluckhohn compiled a list of 160 different definitions of culture (Bodley, 2011). To this day, many scholars argue that there is no universally valid scientific definition of culture (e.g., Maletzke, 1996; Straub, 2007), that no “objective” understanding of culture is possible, and that any conceptual reflection is necessarily a construct of the context in which it is carried out (Bolten, 2014: 3). Broad and narrow definitions of culture exist in large numbers, with different emphases depending on the academic discipline (Maletzke, 1996). The broad understanding sees culture as a condition and premise for action, meaning, and communication—something that all humans have, share, and “do.” In a narrower sense, culture refers to civilization itself, the improvement of humanity, and to excellence in the arts and sciences (Soini and Birkeland, 2014: 3). In its widest sense, culture functions as a holistic functional context of structure and process, of homogenization and differentiation (Bolten, 2014: 3).

Against this backdrop, this research does not attempt to define ‘culture’ in isolation. As Baecker (2003): 33, puts it: “the only defining characteristic of the concept of culture is the widespread view that this concept cannot be defined. Anyone who tries anyway is only showing that they are not up to the concept.” While the term ‘culture’ remains theoretically rich and contested, this study refrains from defining ‘culture’ itself. Instead, the focus is on the composite term ‘cultural center’, which is the actual object of policy, practice, and institutional labeling. Attempting to define ‘culture’ independently of its institutional and policy context would risk detaching the analysis from the practical ambiguities that cultural centers embody in empirical settings.

The evaluation of cultural activities does not necessarily require reference to anthropological, ethnological, sociological, or normative concepts of culture. Discussing the essence of such a “search term” (Baecker, 2003: 7) or attempting to break down a “concept of plurality” (Fuchs, 2012: 64) would not contribute to the analytical goals of this study. More relevant is an understanding of the ambivalent distinction between art and culture, particularly in recognizing the social function of art in varying the conditions of communication, consciousness, and perception within society (Baecker, 2010: 17). Accordingly, this study concentrates on the operational clarification of ‘cultural center’ without isolating the term ‘culture’ itself, aligning with established research practice in this field.

Unlike more clearly defined cultural organizations such as museums, libraries, theaters, concert halls, and galleries, where specific activities and functions are readily identifiable, cultural centers encompass a broad and varied range of activities. This diversity makes the definition and classification of cultural centers a significant challenge (Pfeifere, 2022: 29). Nevertheless, recent definitional attempts have been made by Stenlund (2010), Ruusuvirta and Saukonen (2014), Dapkus and Dapkutė (2013), Eriksson and colleagues (Eriksson et al., 2017), Bogen (2018), Järvinen (2019); Järvinen (2021a), Pfeifere (2022), as well as ENCC (2023). Table 1 shows the wide range from short and functional definitions to the attempt to present a lengthy one-fits-all adefinition. The dynamic nature of society and culture requires an open and flexible approach to cultural centers. Kegler notes that as societal needs and conditions evolve, cultural centers must adapt accordingly. Thus, the concept of cultural centers is dynamic and resists confinement to a single, enduring definition (Kegler, 2020: 29).

TABLE 1

| Source | Definition |

|---|---|

| Stenlund (2010) | Public building that hosts a variety of cultural activities or includes several cultural facilities: a concert hall, a library, a theatre, an art gallery, as well as restaurants and cafés that provide a meeting place for people. The cultural centre is a public platform for people to engage in cultural activities and to provide them with a cultural experience |

| Ruusuvirta and Saukonen (2014) | An administrative unit of a municipality or an institution that receives an annual subsidy from the municipality and carries out its own cultural cultural activities |

| Dapkus and Dapkutė (2013) | Legal person established in accordance with the procedure laid down by laws and recognised in accordance with the procedure laid down by this Law that fosters ethnic culture, amateur art through its activities, creates artistic programmes, develops educational, recreational activities, satisfies community cultural needs, and organises dissemination of professional art |

| Eriksson et al. (2017) | A particular cultural institution that often combines art and creative activities (with spaces and technical facilities for exhibitions, rehearsal, performances, workshops) with a focus on diversity (a variety of activities, users and user groups), civic engagement, involvement of volunteers and openness to bottom-up initiatives |

| Järvinen (2021a); Järvinen (2021b) | House of versatile use for cultural activities |

| Bogen (2018) | Functioning, multi-disciplinary centres with some form of physical space and location |

| Pfeifere (2022) | Multifunctional interdisciplinary cultural institutions that provide access to culture and a wide variety of cultural services, promote citizen participation in culture, offer lifelong learning opportunities and perform various other functions |

| ENCC (2023) | A non-profit organisation or a public body that facilitates citizens’ active participation in sociocultural and artistic activities. Cultural centres promote culture and arts, working closely with and within its communities through a strong local network (with neighbourhood community art organisations, private facilities, government-sponsored, activist-run etc.). It can be for instance a community centre, a socio-cultural centre, a cultural house, an art centre, an amateur group, a cultural association, a local artistic-cultural initiative, a folk art centre, etc., as long as it has a strong sociocultural approach with a community outreach programme that empowers people and local community to have a voice in society through arts and culture. Indeed its focus is not on arts and culture themselves, but on using them as a powerful means of empowerment towards its audiences. A cultural centre makes it possible for citizens to be culturally and artistically active, stimulating active citizenship and participatory processes. It sometimes supports artistic creation and production, promotes cultural heritage or runs different cultural sites (museum, library, cinema etc.). A cultural centre doesn’t necessarily need to have its own physical space where it welcomes its audience as long as its activities are implemented on the territory for the local community. It can address the whole community’s needs or have a specific target group within the community (e.g., cultural centres for children or young people), but it is always inclusive. Last but not least, a cultural centre is pluralistic, open to everyone and non-discriminatory, and promotes diversity |

Overview of definitions relating to cultural center source: own compilation of literature.

Method and data

This study uses two different research designs. In a first step, the initial parts of the Walker and Avant (2019) method of concept analysis are used to establish a) defining attributes of the concept cultural center and b) real-life indicators to detect the presence of these attributes. In a second step, these indicators are used to analyze Finland’s cultural center landscape, based on Statistics Finland’s dataset on cultural halls and centers by region (Statistics Finland, 2023). The descriptive method primarily involved organizing and summarizing data into meaningful categories and describing the distributions and characteristics of these categories. The combination of conceptual analysis and descriptive statistical analysis has been chosen to distinguish between different types of cultural facilities and to provide a more nuanced picture of cultural facilities in Finland. Based on the analysis, this article proposes a new typology of the facilities that operate under the term ‘cultural center’.

This study explores a cross-disciplinary application of the concept analysis method developed by Walker and Avant, which, although originally designed for nursing science, addresses a fundamental scientific concern: the precise clarification and contextual embedding of theoretical concepts. This objective is relevant across disciplines and makes the method particularly appropriate for research areas characterized by conceptual ambiguity. The method “clarifies the symbols (words or terms) used in communication, offering precise theoretical and operational definitions grounded in empirical evidence for both theoretical and practical research applications.” (Walker and Avant, 2019: 167). This process makes it easier to understand and use a concept in research settings. Although the specific Walker and Avant method continues to be predominantly used in fields such as healthcare, nursing (e.g., Haas, 1999; Green and Polk, 2009), or education (e.g., Kaminskienė et al., 2020), concept analysis as a methodological approach is also well-established in cultural policy research. However, cultural policy studies often adopt an interpretative and historical method, focusing on the evolving meanings and applications of ‘culture’ within social and policy contexts. For example, Dubois (2008) examines the genesis of ‘culture’ as a public policy category; Pirnes (2008) analyzes a broad concept of ‘culture’ as a basis for cultural policy and its legitimation in social policy; Lähdesmäki et al. (2020) investigate intercultural dialogue in European education policy documents to assess its societal impact; Silva (2015) traces the term ‘cultural policy’ through its socio-historical evolution in different countries; and Alasuutari and Kangas (2020) analyze UNESCO’s role in shaping cultural policy discourse, making it a global concern. All these studies share a hermeneutic approach that emphasizes the understanding of the historical and ideological evolution of ‘culture’ and its varied applications in policy. Rather than defining ‘culture’ in a fixed way, this interpretive method explores how cultural concepts have been understood, discussed, and applied across contexts, focusing on societal impact and ideological implications in cultural policy. In contrast, the goal of this study is to create a clear, measurable, and operational definition of the concept cultural center. Therefore, a less interpretive and more structured, objective approach—the Walker and Avant (2019) method—was chosen. This method defines core attributes and empirical referents, allowing researchers to identify, measure, and apply the concept consistently. It is ideal when a concept requires standardization or clarification for practical use, such as in creating assessments, interventions, or research measures.

The study applies the Walker and Avant method in the following steps. First, key characteristics commonly used to describe cultural centers were identified based on recent literature (Table 1). Following Haas, (1999): 733, these characteristics were then grouped into four recurring themes, each representing a distinct set of qualities (Table 4). These themes correspond to Walker and Avant’s defining attributes, which capture the core aspects of a concept. To make these attributes practical and observable, empirical referents were identified that provide evidence of the characteristics within the four major categories. The checklist in Table 3 details the empirical referents and their indicators, showing how they were traced in practice. Although the Walker and Avant concept analysis method is useful for structuring complex concepts, its application within cultural policy and infrastructure introduces linguistic challenges. These arise as it re-evaluates previous definitions and employs terms that have varied interpretations in cultural policy, such as ‘indicators’ (Karttunen, 2012: 135). To address these challenges and ensure consistent interpretation, Table 2 provides a glossary that clarifies key terms, enhancing conceptual precision.

TABLE 2

| Term | Usage |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | General features or traits that are found in the literature to describe a cultural center’s functions, values, and organizational structure. Table 4 shows how they are grouped under overarching headings. Characteristics offer a more detailed look at how each defining attribute might manifest in different cultural centers |

| Cultural Center | While conventionally used as a broad term that refers to an umbrella concept, this article uses it as a specific term referring to a specific concept distinguished by four defining attributes |

| Cultural Facilities | Broad term used to describe general-purpose venues or spaces that provide access to cultural activities or events but do not exhibit all defining attributes of cultural centers. Table 5 shows an overview of different cultural facilities identified in this study |

| Defining Attributes | Technical term by Walker and Avant (2019): core qualities that define a concept’s identity. Their presence distinguishes the concept from related ideas |

| Empirical Referents | Technical term by Walker and Avant (2019): real-world phenomena that demonstrate the existence of a concept by emodying ist defining attributes |

| Indicators | Measurable signs that reveal defining attributes in practice, helping to identify and classify cultural centers |

Glossary source: own compilation.

The developed tool was applied to analyze the landscape of cultural centers in Finland as presented in a dataset on Cultural halls and centers by region (Statistics Finland, 2023). This dataset represents one of the more informally gathered datasets by Statistics Finland (Pitkänen, 2023). Previously updated annually based on a statistician’s expertise, the process now includes a two-step verification: checking each entry for activity online, followed by a search for new establishments using the terms culture center and culture house, along with the names of all Finnish municipalities. According to Statistics Finland, this dataset is not intended to comprehensively cover every cultural house in Finland but aims to provide as detailed an overview as the available resources allow, given the broad and loosely defined nature of ‘culture house’ in the Finnish context. With each update, the table is revised to ensure it contains the most current information, replacing outdated data (ibid).

At the time of analysis (March 2024), the original dataset contained 315 entries. A duplicate check was conducted to prepare the dataset for analysis. Following this, filtering criteria were applied to enhance methodological clarity. Specifically, entries containing the words ‘hall’ (25 entries), ‘children and youth’ (19 entries), and ‘student house’ (5 entries) were removed. This filtering aimed to reduce variability in the dataset, thereby facilitating clearer pattern identification. In accordance with the Walker and Avant method, facilities primarily focused on children were excluded, as this paper examines and builds on literature concerning community engagement among the adult population. After this filtering step, the dataset was reduced to 266 entries, which formed the basis for the analysis.

The analysis relied on official websites and available Facebook pages as primary data sources, as these are the most commonly used platforms across the dataset. They provided accessible and relatively standardized information on each facility’s purpose, history, and activities. Other platforms, such as Instagram or LinkedIn, were considered but proved to be inconsistently used across facilities, making them less suitable for a systematic comparison. The analysis period extended from March 19 to March 26, 2024. During this time, seven cases were removed because they lacked recent or accessible information:

- 2 entries had unavailable websites and lacked a Facebook page,

- 2 entries had websites explicitly stating they were not currently operational,

- 3 entries had neither a website nor Facebook updates since 2021

The analysis of the remaining 259 entries focused on detecting the presence of empirical referents. These referents could be explicitly stated in mission statements or statutes on the facility’s website or be implicitly reflected in the programs offered. The examination of both the official websites and available Facebook pages was conducted systematically, applying the predefined checklist outlined in Table 3. The presence of each defining attribute was determined by the detectability of its empirical referents according to the checklist. Only if both components of the defining attributes (e.g., provider AND creator) were traced was the presence of the attribute considered confirmed. The checklist shows a diverse number of different indicators for each empirical referent. While not every single empirical referent needs to be present, at least one had to appear for each of the two components of the defining attributes to confirm their presence.

TABLE 3

| Defining attribute | Emperical referents | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Creator and provider |

The facility offers cultural program |

□ Events are traceable through public platforms (event calendar on the website, announcements facebook) □ Website has contact for questions on program |

| The facility is hosting creative and/or cultural events and/or projects |

□ Event calendar shows content □ Website has a contact for booking |

|

| The facility actively produces cultural content for its audience |

□ Program includes at least some parts that are produced internally □ Event calendar shows original content □ Presence of an in-house production team □ Website and/or facebook show annual reports and/or promotional materials highlighting internally developed projects |

|

| Experience and active participation |

Facility offers learning experiences |

□ Program offers regular classes (e.g., weekly dance lessons, digital media training) □ Program offers courses to teach skills (e.g., summer art camps or weekend photography classes, digital media labs) □ Events celebrating various cultural heritages (e.g., multicultural festivals, international film screenings) |

| Facility offers cultural education |

□ Program is partly designed to teach cultural, artistic, and/or historical knowledge (e.g., exhibitions with guided tours) □ Educational programs for specific groups (e.g., children, youth, seniors, or underserved communities) are part of the program □ Program explores local history and/or traditions (e.g., local heritage workshops and/or lectures) □ Program shows collaboration with historians, anthropologists and/or community elders |

|

| Facility provides platforms for underrepresented voices and marginalized communities |

□ Program is showing events in support of marginalized and/or underrepresented groups (e.g., immigrant art showcases, refugee concerts) □ Publicly supporting social movements through curated programs (e.g., art for human rights exhibits) |

|

| Facility brings various cultural expressions together under one roof |

□ Hosting events that blend art forms (e.g., music and dance, multimedia performances) □ Program shows cultural fusion (e.g., cuisine-themed events) □ Shared spaces are open for different artistic disciplines (e.g., studios, rehearsal rooms) |

|

| Facility offers audience the possibility to engage within the program | □ Program shows activating eventforms (e.g., workshops, open-stage events, discussions, lectures, impro) | |

| Openness for audience to take part in creation of program |

□ Open calls for program and/or participation □ Evidence of audience feedback mechanisms on the program (e.g., surveys, website and/or facebook asking for feedback, Encouragement for audiences to leave reviews on review platforms) □ Establishment of audience-driven collectives tasked with curating parts of the program (e.g., film clubs, art circles) |

|

| Program offers the possibility for audience to engage in broader social, civic, or political topics |

□ Program shows events addressing current societal issues (e.g., exhibitions on climate change, panels on inclusivity) □ Program shows events on civic topics (e.g., elections, policy reforms) |

|

| Diversity and multidisciplinary | General program is adressing diverse audience |

□ Entirety of the program does not focus solely on a specific age, social, gender, or ethnic group, offering diverse appeal □ Events for specific groups are balanced with broader events for all (e.g., children’s programs alongside adult-focused offerings) □ Event calender and/or program is categorized by age, cultural themes or goups, showing efforts to represent different population groups |

| Program shows opportunities for both participation and observation | □ Program shows both demonstration-based events (e.g., concerts, theater, movie) as well as events with different engagement levels (workshops, discussions) | |

| Combines professional and amateur |

□ Program shows evidence for professionals and amateurs perform and/or exhibition together (e.g., community theater productions featuring local residents alongside professional directors and/or actors) □ The facility offers its spaces (e.g., maker spaces, recording studios, rehearsal rooms) explicitly to both professionals and amateurs |

|

| Program includes more than two different cultural disciplines |

□ Annual or seasonal schedules include events across at least three disciplines (e.g., visual arts, music, theater, movies, readings) □ Event calender and/or program is categorized by discipline, showing representation across art forms |

|

| Interaction and community-orientation | Facility provides possibility to physically meet | □ Program shows on-site and in-person events |

| Facility provides space |

□ Facilities is housing permanent cultural offerings (e.g., galleries, performance spaces, and maker spaces) □ Offers flexible rooms that are used for multiple purposes (e.g., one day for rehearsals, another day for community meetings) □ Facility offers shared spaces (e.g., practice and/or rooms, studios) □ Website provides a contact for renting space |

|

| Facility upholds partnerships and collaborations |

□ Offers residencies and/or visiting artist programs □ Official partnership announcements (e.g., press releases, social media, and/or newsletters) □ Program is showing joint projects and/or productions |

|

| Program shows parts that are specifically designed to address the local community |

□ Parts of the program are adressing local issues (e.g., exhibitions, lectures, discussions or performances) □ Program includes materials and/or events in the languages and/or dialects spoken in the community □ Traceble events tied to local festivals, holidays, or traditions (e.g., fairs, markets) |

|

| Local community is involved in program planning |

□ Program shows collaboration with local organizations, artists, schools, and/or businesses to co-create certain parts of the program □ Facility has advisory boards and/or committees with local representatives actively contributing to program planning |

|

| Local community is taking part in the upkeep of the premises |

□ Evidence of structured volunteer programs for tasks such as gardening, cleaning, or repairs (e.g., talko, community gardening) □ Photographs and/or videos documenting volunteer activities in action |

|

| Facility acts as gathering place for community activities |

□ Availability of free meeting areas for community groups □ Presence of gathering spaces within the facility (e.g., cafés, lounges, community garden) □ Local organizations are conducting community meetings in the facility |

|

| Facility provides community services |

□ Possibility of buying tickets □ Providing access to public facilities like internet stations, printers |

|

| Facility participates in local civic initiatives | □ Traceble evidence for parttaking in charity drives, environmental cleanups, refugee work |

Checklist defining attributes of cultural centers in practice source: own compilation.

With a final sample of 259 entries out of an original 315, the sample size is modest, especially given the study’s broad goal of establishing a typology for cultural centers across Finland. This limited dataset may lack the breadth needed to fully capture the variety and complexity of cultural centers across Finland, where regional, linguistic, and cultural diversity, shaped by a Swedish-speaking minority and the Sámi community, affect how these centers operate and serve their communities. Consequently, the adaptive programming and services that cater to the distinct needs of these groups may not be fully represented in this sample. Both the dataset and research methods in this article carry inherent limitations, as they capture only a single, time-specific view of cultural centers. The data, collected in March 2024 and verified through facility websites, reflects only a brief period in the life cycle of these centers. Given the dynamic nature of cultural centers, which adapt their programming, community engagement, and organizational strategies in response to shifting community needs, policy changes, and cultural trends, this moment-in-time perspective may not fully capture longer-term patterns or transformations. This is proven by the latest update of the table in May 2024. Based on the results of this research, Statistics Finland added 4 facilities to the table (Pitkänen, 2024).

The essence of the concept cultural center

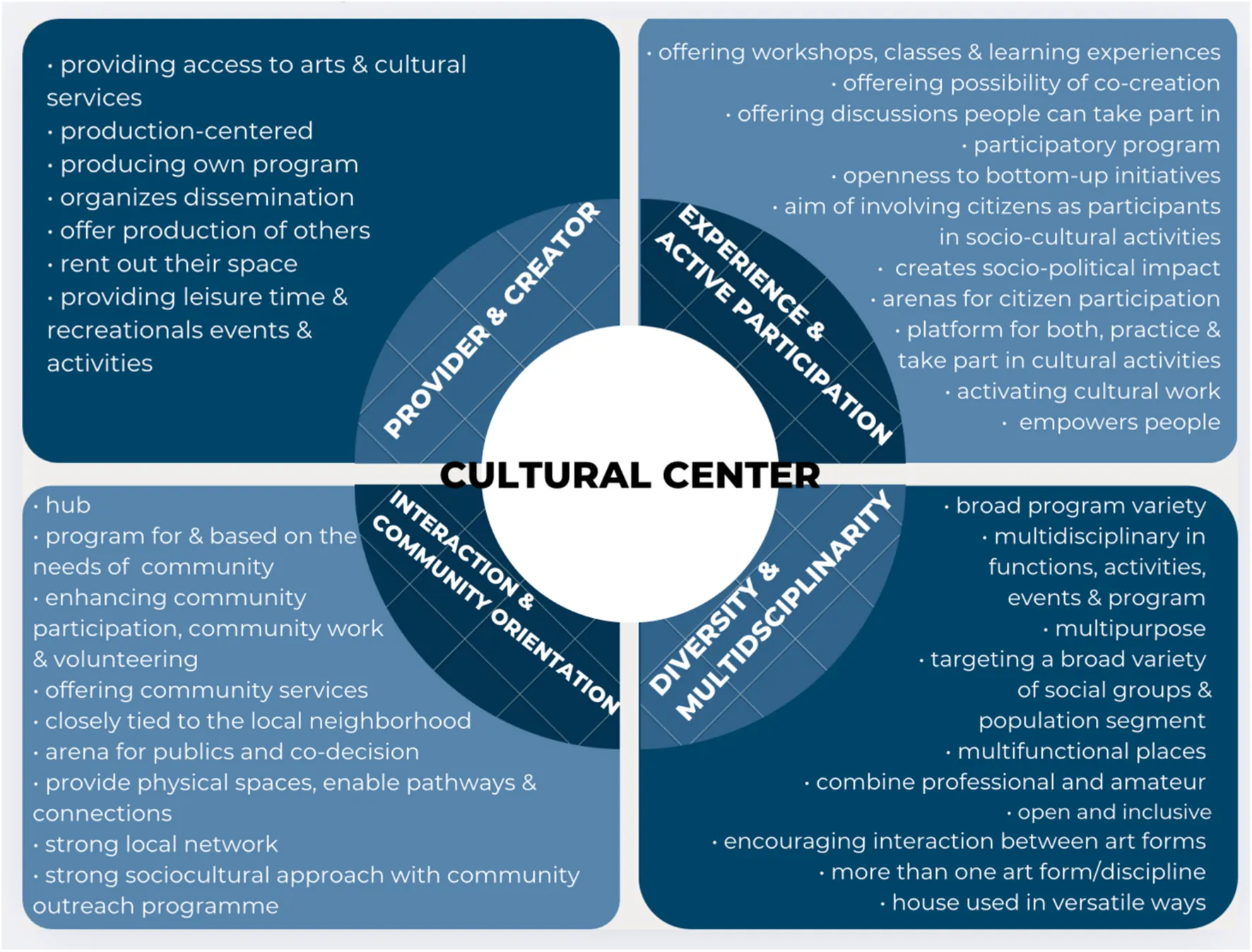

Multiple forms and names result in many attributes that are to be found in the literature to describe cultural centers. What might seem as an obstacle for developing a precise definition in the first place, comes as an advantage for concept analysis, where the breadth of definitions, designations, and structures of cultural centers is highly beneficial, allowing for the recognition of a wide range of applications, both direct and implied (Walker and Avant, 2019: 172). Table 4 shows the categorization of the various descriptions, definitions, and uses of the term in Table 1, grouping them according to four recurring themes that emerged inductively. In line with Walker and Avant, these recurring themes serve as defining attributes. Based on this systematization, empirical referents were developed as expressions of the presence of the attributes. These empirical referents are classifications of real-world phenomena that demonstrate the existence of the concept through their presence (Haas, 1999: 738). Table 3 shows the detailed list of empirical referents belonging to each defining attribute and the indicators of how they can be traced in practice.

TABLE 4

|

Defining attributes of the concept cultural center source: own compilation.

This structured progression from the diversity of conceptualizations in the literature to a system of defining attributes, empirical referents, and practical indicators forms the conceptual foundation of the study. It ensures that the typology developed in Chapter 6 is firmly grounded in both theoretical insights and systematically derived operational criteria (see also Table 5). The attributes derived in this way not only clarify the conceptual understanding of cultural centers but also enable a consistent application to empirical data, ensuring analytical transparency and comparability.

TABLE 5

| Type | Provider & Creator | Experience & Participation | Diversity & Multidisciplinary | Interaction and Community Orientation |

Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-cultural Center | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Offer and create a manifold range of cultural program activities to a varied audience, prioritizing inclusivity and reflecting the interests and backgrounds of their community. They provide opportunities for active cultural engagement, allowing both: individuals to experience and participate in cultural encounters as well as engaging the community on multiple levels. They also foster strong community connections serving as gathering places for people to interact, share, and build relationships |

| Specialized Socio-cultural Center | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Fully embody all four defining attributes but with a focus on specific population groups such as children and minorities (Sámi) |

| Focused Cultural Center | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | Close to being socio-cultural centers but having a more focused or specialized offering thus lacking the attribute diversity and multidisciplinary. The degree of specialization or focus might vary significantly as facilities might have a narrower range of cultural disciplines and/or target specific age or population groups |

| Cultural Anchor | ✓ | ✓ | ✓/x | ✓/x | All facilities are a vital source of cultural content, offering a broad range of cultural disciplines for a diverse audience. However, the lack of either of the attributes experience and active participation or interaction and community orientation, show these facilities don’t prioritize active cultural engagement on a personal or community level |

| Creative Production Space | x | x | x | x | Places showcasing artistic output of one or more artists without offering actual program |

| Satellite Venue | x | x | x | x | One out of several components of a larger cultural program, managed by a central provider (e.g., city, theater). Whereas the whole program of the larger cultural provider might meet all four defining attributes, the single place itself does not |

| Venue | x | x | x | x | Places to rent, no program at all |

Overview typology cultural center source: own compilation.

Provider and creator

The first theme that emerged was the hybrid role of cultural centers as both venues for and creators of culture. Authors describe cultural centers as production-centered organizations (Silvanto et al., 2005: 168), producing their own programs (Pfeifere, 2022: 35), while also providing space and facilitating the dissemination of arts and culture (Dapkus and Dapkutė, 2013: 98). Some support artistic creation and production by others or manage multiple cultural sites (ENCC, 2023). In addition to their own programs, they may leverage their buildings, resources, skills, and knowledge to offer a wide range of goods and services, which often play a significant financial role in their business models (Bogen, 2018: 27). To determine if a location functions as both a provider and creator of culture, the initial step is to check for the presence of any program. Does the place offer cultural program, or only space? Without a program, it merely serves as a venue available for private or public events. If programming exists, it’s crucial to ascertain whether it’s produced internally or simply organized to facilitate external content. It can involve both internal and external productions, but to fully align with the concept, it must, at a minimum, include parts of the program that are produced internally. Moreover, when a place does generate its own programming, the emphasis of these offerings should be considered: Is it directed towards engaging an audience, or primarily focused on the interests of those managing the place? The core attributes of a cultural center are inherently audience-oriented. A site lacking programming aimed at an audience cannot qualify as a cultural center. An example of this distinction could be an artist’s residence and studio, which, while possibly hosting public exhibitions and workshops, centers around the artist’s production rather than audience engagement, thereby diverging from the cultural center model.

Experience and active participation

The second theme was experience and active participation. The possibility of participating in amateur art activities, professional art cognition and acquisition of new competences (Dapkus and Dapkutė, 2013: 99), the possibility of both doing and watching (Silvanto et al., 2008: 15) are repeatedly described. The participatory profile of the centers, their practice and understanding of participation might differ but they all incorporate people’s involvement and a focus of with the people rather than just for the people: it is active participation that is at the very heart of cultural centers (Eriksson et al., 2017: 28). Authors highlight cultural centers as places offering diverse artistical and cultural participation opportunities (Pfeifere, 2022: 35), stimulating active citizenship and participatory processes (ENCC, 2023). The aim is creating a platform, where individuals can actively engage in cultural endeavors and partake in various cultural activities (Järvinen, 2021b: 1), emphasizing people’s own activities and their own notion of culture and their own needs (Silvanto et al., 2008: 11). Some authors describe cultural centers being important educational institutions where artistic, personal, social, professional, communicative, and other abilities can be acquired (Dapkus and Dapkutė, 2013: 100) in form of education or participatory activities such as workshops, classes, debates, and lectures (Bogen, 2018: 27). Literature also stresses the fact, that participation extends beyond mere involvement in cultural or social events at the cultural center. The activities conducted within these centers are not merely standalone, self-sufficient occurrences. Rather, they are implicitly or explicitly regarded as components that foster or enable diverse kinds of progressive change, not just within individual citizens and local communities but can also ripple out to impact broader societies (Eriksson et al., 2017: 18). The aim is not to reach an audience in the sense of viewers or listeners, the focus is on active and joint participation in shaping society within the respective local or regional society as the nucleus of the global world (Kegler, 2020: 110).

To assess the attribute of experience and active participation, examining the nature of program activities is crucial. Are these activities merely passive events for observation, or are they crafted to encourage audience engagement? Examples might include workshops, open-stage events, or lectures. Experience also encompasses the physical aspect of meeting people and sharing spaces. Does the place bring various cultural expressions together under one roof? Or does it provide residencies? Either scenario presents a tangible method to confirm that the venue embodies this attribute.

Diversity and multidisciplinary

The third theme developed around diversity in the audience and the multidisciplinary of cultural disciplines. Authors describe cultural centers as a house used in versatile ways for cultural activities (Järvinen, 2019: 2), ranging from cooking classes to chamber music concerts (Silvanto et al., 2008: 15). Authors stressed cultural centers as multi-functional (Dapkus and Dapkutė, 2013: 99), multi-disciplinary (Bogen, 2018: 11), pluralistic and inclusive (ENCC, 2023), with diversity being key in terms of activity, audience as well as program (Eriksson et al., 2017: 3). Hosting diverse activities and attracting audience groups of different social background, age and interest is described to increase contact between people and activate them and make it possible to transgress the borders of different forms of the arts. (Silvanto et al., 2008: 10). Diversity as an attribute also refers to the different functions cultural centers are assigned to, as they have not only performed cultural functions but also educational, leisure/recreation, and various social functions (Pfeifere, 2022: 35).

To verify diversity, it’s essential to evaluate both the audience and the program. Diversity among the audience implies that the program caters to a wide range of individuals. While certain events may focus on specific demographic groups, the overall program should not exclusively target any single group. Diversity in programming involves offering opportunities for both participation and observation. Active participation is indeed a fundamental aspect of a cultural center’s ethos. However, venues that solely provide workshops lack programmatic diversity. For a program to be considered multidisciplinary, it should encompass more than two disciplines, illustrating a breadth of cultural engagement.

Interaction and community-orientation

The last theme to emerge centered on physical interaction between people coming to the cultural centers, as well as between the cultural centers and the surrounding community. Cultural centers not only provide access to a range of activities, but also to physical spaces (Eriksson et al., 2017: 24). They are described as gathering places where community members can realize their natural needs for communication, collaboration and improvement (Dapkus and Dapkutė, 2013: 100). Compared to other types of cultural institutions, authors describe cultural centers as more open to various forms of engagement in conversations and other interactive processes, serving as important arenas for publics and co-decision (Eriksson et al., 2017: 20). Cultural centers are tied closely to their community (ibid.: 3) as they work with and within their communities through a strong local network (ENCC, 2023). Authors highlight the socio-cultural dimension of a cultural center with a strong focus on local communities (Pfeifere, 2022: 31). Cultural centers are also described in a double role as both venues for national, or even international, productions as well as cradles for local cultural activities (Silvanto et al., 2008: 22).

Empirical referents of interaction and community orientation can be observed in both the target audience and the groups utilizing the space. Shared spaces not only serve as a marker for experience. The availability of space for local organizations to conduct their activities is also a tangible sign of interaction. Programs specifically designed to engage the local community, such as lectures on community issues, discussions, fairs, or markets, also illustrate this attribute. Additionally, indications on the website that the local community is invited to participate in program planning or in the upkeep of the premises through volunteer activities highlight a commitment to community involvement. Moreover, some venues may provide various community services, further demonstrating their orientation towards serving and integrating with the local community.

Traits and types of cultural centers in Finland

Building upon the conceptual analysis outlined above, a checklist of empirical referents was developed for each defining attribute of a cultural center. These referents were selected based on their observability in practice, ensuring that the attributes could be reliably traced in real-world institutions (see Table 3). The dataset consists of 259 facilities labeled as cultural centers, whose websites and Facebook pages were systematically analyzed using this checklist.

The results highlight a wide variation in how these facilities align with the four defining attributes. Only 50 entries (19.31%) fully embody all four attributes. Among these, six centers (12%) specialize in specific demographic groups, focusing on either children and youth (5 entries) or Sámi culture (1 entry). Beyond this core group:

• 31 entries (11.97%) fulfill three of the four defining attributes.

• 37 entries (14.29%) fulfill two attributes.

• 45 entries (17.37%) fulfill only one attribute.

• A substantial portion - 95 entries (36.68%) - do not fulfill any of the defining attributes.

Notably, 36.68% of the entries do not exhibit any of the core attributes, suggesting a trend of labeling various facilities as cultural centers, despite their lack of alignment with these defining characteristics. This indicates that the term ‘cultural center’ may sometimes be used broadly or even inflatedly, perhaps to confer prestige or attract attention. Furthermore, the broad variety of entries of different facilities in this group underscores the diversity and complexity within this category in Finland and reinforces the necessity for a more refined typology in the categorization, as proposed in this article, to better capture the range of facilities operating under this label.

Traits: patterns of attribute fulfillment and absence

The distribution of the defining attributes across the dataset reveals some clear patterns. Diversity and multidisciplinarity is the most commonly absent attribute. It is absent in all facilities that fulfill only one attribute. It is also the most frequently missing characteristic (29 entries) among facilities that fulfill three attributes, meaning that these centers otherwise exhibit strong engagement, participation, and community interaction, but do not integrate multiple disciplines. Active participation and experience is slightly less absent, especially in categories where two or three defining attributes are missing. The least missing attribute is provider and creator, which is the most consistently present across all groups. Among facilities that fulfill only one attribute, only four lack this characteristic. This suggests that a lot of entries in the dataset function as producers and initiators of cultural activity, even if they lack other defining attributes. If only one defining attribute is missing, it is seldom community-orientation and interaction, only one out of the 31 entries in the three-out-of-four-group was short on this attribute.

As the number of defining attributes decreases, two clear trends emerge. 1. The level of engagement and the connection to the surrounding community decrease with the number of present attributes. Facilities that lack only one defining attribute tend to have a narrower scope in terms of the disciplines they offer and the audiences they engage. Whereas once two or more attributes are missing, the level of active participation and community involvement declines significantly.

2. Facilities with no defining attributes form a heterogeneous group. The biggest group in the analysis is the one meeting no defining attribute at all: 95 out of 259 entries (36.68%) do not fulfill any of the four defining attributes of the concept

cultural center. This is a remarkable finding, as it indicates that a considerable number of institutions labeled as cultural centers do not align with the core characteristics associated with such facilities. This is a highly diverse group, i.g., including:

• Places to rent (37 entries) –for public or private events without a cultural program.

• Restaurants (7 entries) – with or without hosted events, all lacking structured cultural activities.

• Education centers (3 entries) – spaces with a focus on educational function but without interdisciplinary or participatory components.

• Concert halls (3 entries) – places that host cultural events but do not engage in community-building or participatory programming.

• Leisure parks (2 entries)

• A shopping mall with a library and rentable space, suggesting that the label ‘cultural center’ is sometimes applied loosely.

• A youth center/UF.

The fact that only 50 out of 259 entries (19.31%) fully embody all four defining attributes highlights the variability in how cultural centers are understood and operate. This naturally raises the question of whether the defining attributes have been appropriately chosen. A significantly larger number of facilities would meet the criteria if interdisciplinarity were used instead of multidisciplinarity—that is, if the presence of just two different disciplines were sufficient. However, this distinction is not merely semantic: while interdisciplinarity allows for collaboration between two fields, multidisciplinarity ensures a broader integration of cultural forms, leading to greater variety in programming and audience engagement. This qualitative difference directly affects program variety, making multidisciplinarity a more robust criterion for capturing the full diversity of cultural centers.

Types: clustering attributes for a more refined typology

While the previous section analyzed which attributes are present or missing, the next step is to cluster facilities that share similar attribute distribution patterns to propose a more precise typology of cultural centers.

Out of the 50 entries matching all defining attributes, six had a focus on specific groups (12%): three focused on children (62%), two on youth and young adults and young ones (4%), and one had a focus on Sámi culture (2%). The remaining 44 stand out as comprehensive cultural institutions as they fully embody all four defining attributes. These facilities offer a wide range of programs activities that engage the community on multiple levels, they prioritize inclusivity and reflect the interests and backgrounds of their community. They provide opportunities for active cultural engagement, allowing individuals to contribute to the cultural dialogue through participatory experiences. They also foster strong community connections, serving as gathering places for people to interact, share, and build relationships. With their focus on culture, active participation and the surrounding society, they can be seen as analogous to what is referred to as sociocultural centers (Kegler, 2020: 29; Ranczakowska et al., 2024: 7). This is why the term socio-cultural centers will be used to describe them, whereas those six entries that fully embody all four defining attributes but with a focus on specific population groups are referred to as specialized socio-cultural centers.

A closer look at the 95 entries that matched none of the defining attributes showed that the largest number (37 entries) were places to rent for public or private events (38.95%). They differ in size or ownership and can be situated, e.g., in restaurants, historic buildings, schools, or student dorms, but they all share the fact that they don’t have any program at all. As they are just places to rent, the term venues was chosen to refer to them. 11 entries (11.58%) are part of a larger cultural offering managed by a central provider, such as a city (9 entries) or a theater (2 entries). These facilities contribute to the overall cultural landscape and participate in a shared event calendar, even if they individually do not meet all the criteria to be considered comprehensive cultural centers on their own. The term satellite venue was chosen for this group to emphasize their role as extensions or components of a larger cultural strategy or program. Some entries in this group offered services in the widest sense, but no cultural program: education centers (3 entries), a youth center/UF (1 entry) or a community center (3 entries). Three entries were municipal centers with an included library. Five entries in this group function as an atelier and a showroom of one or more artists. Focusing on different disciplines, they all share one similarity as they focus on showcasing their artistic output without offering an actual program. According to their production-based focus, the term creative production spaces was chosen to refer to these facilities.

The group with one defining attribute missing shows a total of 31 entries. For 29 of them (93.55%), the attribute diversity and multidisciplinary is missing. These facilities are close to being socio-cultural centers but have a more focused or specialized offering. Although they all serve as platforms for emerging artists and community members to actively participate in and create culture, fostering community engagement through the arts, the grading of specialization or focus of these entries might differ significantly. It might be that they have a narrower range of cultural disciplines, but they could also focus on a specific age or population group. These facilities are referred to as focused cultural centers to capture their more specialized offerings. Out of the remaining 2 entries, both active participation and experience and community-orientation and experience are missing in one entry (3.23%). Both entries excel in offering a wide range of cultural programs and disciplines, serving as vital sources of cultural content. However, they may not emphasize opportunities for the community to actively participate in creating culture or may not prioritize fostering deep community connections and interactions. The term cultural anchors is used to illustrate the critical role these facilities play in enriching the cultural landscape and providing access to diverse cultural experiences. Table 5 provides a systematic overview of the naming conventions and the assignment of facility types based on the presence of the four defining attributes gives an overview of the refined typology that allows for a more precise classification of cultural centers, moving beyond the binary fulfillment of attributes and acknowledging varied institutional roles in the cultural ecosystem.

Findings and implications

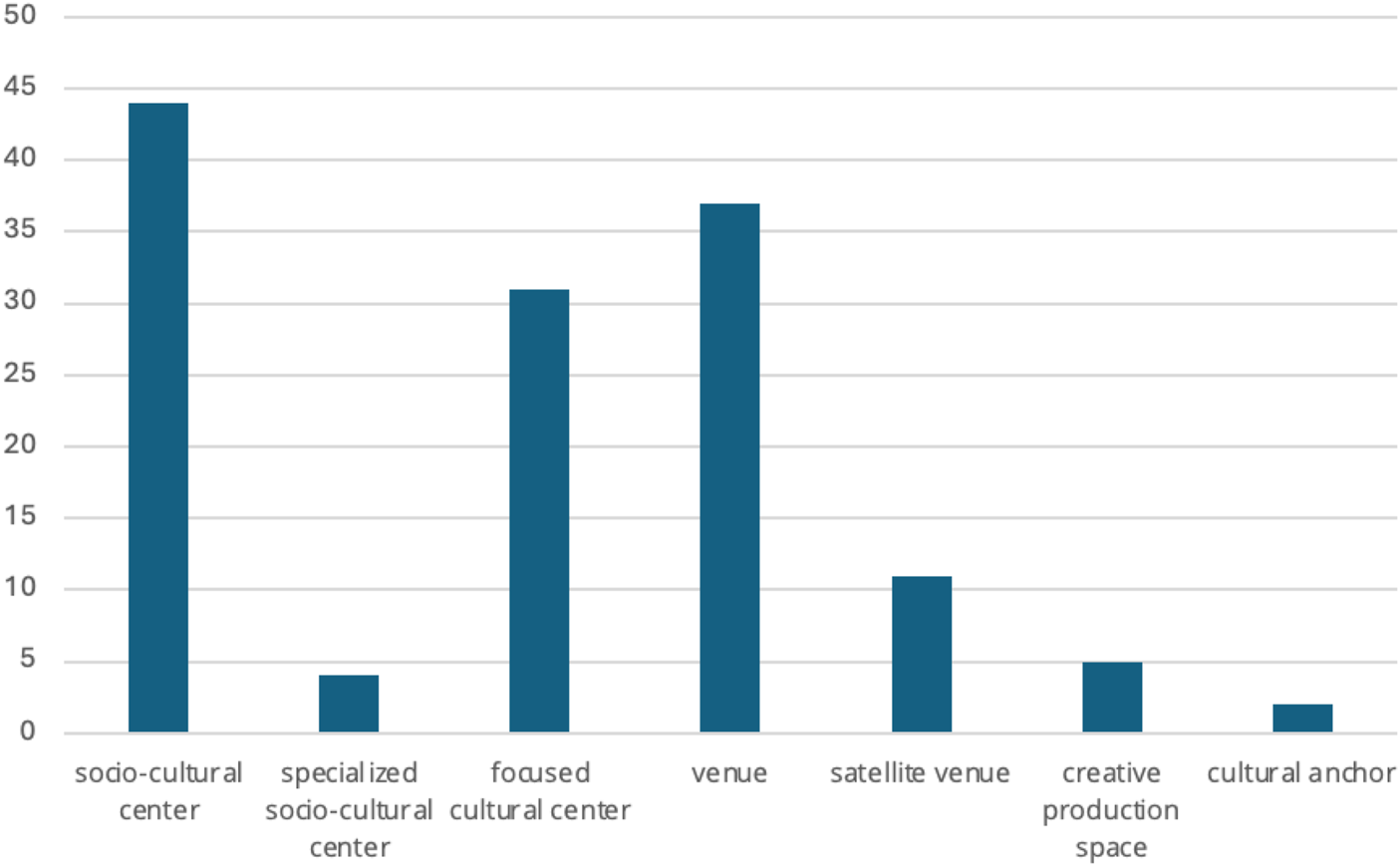

This study aimed to clarify the concept of cultural centers by addressing three key research questions: (1) What is the essence of the concept of a cultural center? (2) What aspects differentiate cultural centers from other cultural facilities? (3) How can the different facilities operating under the name ‘cultural center’ be traced in practice? By applying a structured concept analysis, this study refines the definition of cultural centers in a way that moves beyond previous research, which often conflated different types of cultural facilities under a single label. The identification of defining attributes and the proposed typology contribute to a more precise and operationalizable understanding of cultural centers, making future comparative research more feasible. It became obvious that cultural centers are not a monolithic category but encompass a wide variety of institutions with differing levels of engagement, community involvement, and programmatic scope. The empirical analysis of 259 facilities revealed that only 50 fully meet all four defining attributes, while over a third (95) do not embody any of them. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of the classified cultural facility types. This distribution reflects the diversity of cultural facilities in practice and underscores the utility of the developed typology for distinguishing between them. It reinforces the conclusion that the term ‘cultural center’ is often used in a broad and inconsistent manner, sometimes encompassing facilities that serve entirely different functions. As defined here, cultural centers are facilities that provide artistic and socio-cultural content to society. They are diverse in their goals, origins, organizational forms, and focal points, yet are distinguished by four defining attributes: provider and creator, experience and active participation, diversity and multidisciplinary, and interaction and community orientation.

FIGURE 1

Distribution of cultural facilities source: own illustration based on classified facilities (see Chapter 6).

The typology proposed in this study differentiates between socio-cultural centers, specialized socio-cultural centers, focused cultural centers, cultural anchors, venues, satellite venues, and creative production spaces. This refined classification provides a practical tool for distinguishing various cultural facilities operating under the same label. This typology is not only a conceptual framework but is also intended as a practical tool for cultural practitioners, researchers, and policymakers. Cultural practitioners can use the typology for self-assessment and strategic positioning, for example, by reflecting on which attributes they already fulfill and where further development might be possible. Researchers may employ the framework to structure comparative analyses across regions or countries, enabling a more nuanced understanding of cultural infrastructure. Policymakers can apply the typology to design differentiated funding strategies, distinguishing between facilities that align with sociocultural objectives and those primarily serving as rental venues.

In the Finnish context, applying this typology systematically is particularly valuable for capturing the diversity of cultural infrastructure across the country. This includes recognizing the needs of different linguistic groups, especially the Swedish-speaking minority and the Sámi community. Moreover, a differentiated assessment is essential for mapping cultural facilities in rural and sparsely populated areas, where access to cultural services is often limited but vital for social cohesion. A practical application of this typology would involve using the checklist from Table 3 to classify facilities, followed by mapping their regional distribution to inform cultural policy, research, and infrastructure planning.

Discussion

The preceding chapters developed a conceptual framework for cultural centers, tested it empirically, and proposed a typology based on four defining attributes. This raises important considerations about the selection of literature, the transferability of the methodological approach, its descriptive focus, and the boundaries of the dataset. At the same time, the findings speak to broader questions about the visibility of cultural centers within cultural policy, the gaps in current data collection practices, and the role of cultural centers in supporting cultural participation, particularly in rural and linguistically diverse regions.

Methodology

The selection of literature in this study specifically addresses cultural centers, their functions, classifications, and organizational models within the European context. While this targeted selection ensured relevance to the empirical phenomenon under investigation, it was not conducted as a formal systematic literature review. A systematic or integrative review could further consolidate the conceptual basis and potentially reveal alternative dimensions or typologies. In addition, engaging more deeply with broader theoretical perspectives—for example, from cultural sociology or spatial studies—could further enrich the conceptual framework developed here. For example, Oldenburg’s (1999) concept of Third Places, briefly outlined here, offers an analytical perspective for understanding the social function of cultural centers as low-threshold spaces of encounter situated between private and public life. This could help to better grasp the role of cultural centers not only in their cultural, but also in their socio-spatial significance. Such perspectives might offer additional insights into the socio-cultural and spatial dynamics of cultural infrastructure, including their role in community formation and identity construction. While this was beyond the scope of the current study, it presents an important direction for future research.

The cross-disciplinary application of a method originally developed within the health and nursing sciences may seem unusual at first glance. However, in interdisciplinary fields such as sustainability research, spatial studies, or cultural policy, conceptual clarification is particularly important, as different disciplinary understandings converge. The systematic framework provided by Walker and Avant can help to structure, clarify, and communicate vague, ambiguous, or normatively charged concepts in a more transparent and comprehensible way, even without any direct connection to the health sciences. The method thus offers a valuable tool for establishing transdisciplinary foundations for mutual understanding.

The methodological design of the study prioritized conceptual clarity and consistency in data collection. However, these strengths come with certain limitations that open up avenues for further research. The following reflections address these constraints and suggest directions for expanding the empirical and theoretical insights generated here. One limitation to acknowledge lies in its exclusive reliance on websites and Facebook pages. While these platforms offered the most consistent and accessible information across the dataset, this approach may have excluded less formalized or different forms of communication, such as Instagram or other social media channels. Moreover, while the information provided through these sources is generally reliable for documenting official activities and institutional profiles, it may not fully capture the informal, evolving, or less institutionalized aspects of cultural centers. Future research could complement this approach with additional qualitative methods or broader social media analyses to capture more informal or ephemeral cultural activities.

Another limitation concerns the filtering of the dataset, specifically the exclusion of children’s and youth facilities. This decision was based on the focus of the concept analysis, which aimed to clarify the attributes of general cultural centers rather than specialized institutions serving distinct demographic groups. However, this filtering inevitably narrows the scope of the findings and may overlook important aspects of community-based cultural infrastructure. Future studies could address this gap by applying a similar analytical framework to facilities targeting specific populations, thereby enriching the understanding of cultural infrastructure in its full diversity.

Relevance of the findings

The typology developed in this study provides a structured classification of cultural centers but remains conceptual and untested in practical policy settings. Nevertheless, it offers a valuable framework for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to better understand and differentiate cultural facilities operating under the same label. Future research could explore its practical applicability in areas such as policy design, funding strategies, and the planning or evaluation of cultural infrastructure. As the term ‘cultural center’ is used variably across Europe and beyond, a clearer classification system can help inform international comparisons, cultural statistics, and cross-border policy learning. Further validation through comparative studies and engagement with policymakers is necessary to ensure the typology’s applicability across different cultural and administrative contexts.

Beyond administrative and statistical considerations, a clearer understanding of cultural centers is essential for strengthening social cohesion, cultural participation, and regional equity. In Finland, where linguistic minorities such as the Swedish-speaking population and the Sámi community maintain distinct cultural identities, recognizing and supporting appropriate cultural infrastructure is crucial for fostering inclusion and cultural rights. In rural and sparsely populated regions, cultural centers often represent not just venues for culture but key platforms for social engagement, education, and civic participation. Thus, the typology contributes not only to scholarly and policy debates but also to broader societal efforts to ensure equitable access to cultural resources across diverse communities.