Abstract

Fashion archives, as repositories of cultural memory, often reflect and perpetuate colonial legacies through their curation, classification, and accessibility practices. This paper investigates how digital technologies can serve as transformative tools for decolonising fashion archives, enabling inclusive knowledge production and equitable access. Grounded in a postphenomenological framework, the study explores user interactions with digitalised archives. Using a case study approach, this research examines exemplary initiatives where cultural institutions have leveraged digital tools to reimagine archival narratives. The selected cases highlight the potential of digital innovation to preserve intangible heritage and foster dynamic experiences. Findings reveal how digital technologies mediate the relationship between cultural artefacts and audiences, challenging traditional power structures within heritage institutions. By drawing connections between decolonial archival praxis and empirical outcomes, this paper provides actionable insights for researchers, archivists, curators, and designers aiming to build archives through a decolonial lens. This study contributes to the broader discourse on heritage, decolonisation, and digital transformation within the fashion sector, offering a roadmap for bridging the physical and digital realms.

Introduction

Archives can be generally understood as a site where documents, artefacts and other records are systematically stored and maintained, often behind defined agendas. Archives serve various purposes, from monitoring data, providing direct access to curated information for historical research, and maintaining national memory. This maintenance however has not always been possible as the archival national memories of colonial and post-colonial nations was often displaced to European centers, complicating how information is archived and accessed (Featherstone, 2006). A crucial factor in how archival practices support persisting colonial practices regards how archives are proposed as sources of information, accessed without a critical contextualisation of artefacts (Stoler, 2002).

In this study, we take a perspective that understands that archives do not merely serve as passive repositories of historical records but are active participants in producing knowledge. They shape what is visible, whose voices are heard, and whose histories are preserved. This critique aligns with broader movements toward decolonising cultural spaces, where the restitution of looted objects–such as the Benin Bronzes or the Parthenon Sculptures–and dismantling colonial statues and monuments have become significant acts of redress (Gregg, 2022). These movements underscore the need for archives to be reconceptualised as sources of historical inquiry and as sites of ethical responsibility and active reparation. Additionally, such movements understand that critiquing the underlying colonial frameworks often underpin archival practices is crucial. By naming or defining categories, archives effectively impose a lens of authority on the material they present, holding power over the communication and centralisation of history and knowledge. The processes of selecting, categorising, and preserving objects reflect a legacy of exclusion and control, perpetuating hierarchical narratives that privilege Eurocentric histories over others (L'Internationale, 2016).

Moreover, Indigenous and culturally specific fashion practices have also gained increasing visibility through platforms such as Indigenous Fashion Weeks in Vancouver, Toronto, New York, and Paris, the Amazonia Fashion Week, as well as international showcases like the Cannes Indigenous Arts and Fashion Festival (Indigenousfashionarts, 2025). These events reflect a growing global awareness of the artistic, cultural, and historical significance of traditional dress systems and their contemporary reinterpretations. However, this surge in visibility exists alongside persistent issues of cultural appropriation, where major fashion houses extract and commercialise elements of folk costumes and Indigenous designs without proper credit, collaboration, or benefit to the communities of origin. Notable examples, such as Dior’s uncredited use of Mexican textile traditions or Louis Vuitton’s adoption of South African Basotho blankets, highlight the tensions between creative innovation and exploitation (Pieti and lä, 2020). These practices often reduce cultural heritage to aesthetic commodities, perpetuating historical dynamics of extraction and marginalisation (Beltrán-Rubio, 2020). Digital platforms and social media have played a central role in making such tensions visible and supporting the development of a better-informed discourse on cultural heritage and appropriation (Vänskä and Gurova, 2022). In this work, we are interested in further understanding how technology and digital innovation can enable decolonising fashion and textiles, especially from the perspective of the digital archives.

The institutionalisation of fashion archives, particularly within museums, has historically reflected colonial hierarchies of value. The earliest fashion collections prioritised non-Western dress while excluding contemporary Western garments, framing the former as ethnographic curiosities and the latter as commercially transient (Taylor, 1998; Martin and Vacca, 2018). This selective preservation reinforced broader narratives in which non-Western fashion was frozen in time, stripped of its contemporaneity and repurposed to serve colonial knowledge systems. Fashion theory itself remains entangled with Eurocentric frameworks, where the modern, creative, and innovative are implicitly aligned with the West, and the vernacular or Indigenous is cast as static or obsolete (Jansen, 2020). Within this context, archives not only preserve garments but also encode ideological structures that determine which bodies, aesthetics, and histories are considered legitimate. As such, calls to decolonise fashion archives require more than diversifying collections; they necessitate interrogating the taxonomies, temporalities, and display practices through which fashion heritage is rendered knowable. In this light, digital technologies may offer possibilities for alternative modes of curation, attribution, and engagement, but only if critically oriented to address these structural imbalances from the outset.

Recently, archives have also served the purpose of creating windows of visibility to the general public. Within this space, the ability of clothing, dress, and other fashion-related items, to reflect historical contexts has recently favoured the archival of such artefacts (Peirson-Smith and Peirson-Smith, 2020). Identifying fashion as an attractive topic for an increase in visitors’ demographics and profit revenue has driven a multiplicity of initiatives exploring fashion archives, especially within museum spaces (Beltrán-Rubio, 2020). As described by Martin & Vacca (Martin and Vacca, 2018), as fashion’s popularity in museum contexts has grown, so too has its value as a medium for the transfer of knowledge; fashion objects are uniquely situated to evoke memory and cultural meaning: embedded in everyday life, aligned with popular culture, and capable of conveying histories of identity, labour, and materiality. In this context, museums have assumed a vital role in shaping narratives around fashion heritage, and the archive has become a strategic tool for preservation, branding, education, and research. The archive embodies a layered system of creative, industrial, and symbolic practices, with items often connected to design documentation, production processes, and broader socio-historical contexts. (Martin and Vacca, 2018).

This role has become even more significant within the “knowledge economy,” where intangible assets such as heritage, identity, and know-how hold increasing cultural and commercial value (Vacca et al., 2023). However, the challenge lies in how to render visible the creative and technical processes behind garments, including their material construction and use. “Augmented archives” now offer multisensory, participatory experiences that expand the archive’s reach (Martin and Vacca, 2018) and redefine it ontologically. Technologies like 3D scanning, AR, and VR allow institutions to animate garments simulating motion and constructing immersive environments (Vacca et al., 2023). VR can digitally reanimate garments to demonstrate how a piece was meant to move and be worn. AR overlays, QR codes to scan with smartphones, and interactive kiosks allow audiences to access relational content, deepening their understanding of fabrication techniques, symbolism, and cultural significance (Martin and Vacca, 2018; Vacca et al., 2023; Pecorari, 2019).

Though existing for a few decades, digital archives have proliferated, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, pushing museums and archives to digitise their collections to maintain public access. The opportunities brought by digital archives are plentiful as they remove geographical barriers and can offer alternative ways of engagement between visitors and the materiality of the archive, potentiating their agentic dimension. By digitising collections and creating web-native archival configurations, museums and fashion houses may rethink how knowledge is stored, shared, and produced. This potential has also affected digital archives’ engagement in critiquing colonial frameworks (Schnapp, 2016), interrogating how digital tools are rearticulating the epistemic, political, and affective dimensions of fashion heritage.

Growing questionings of western conceptualizations of fashion and movements such as afrofuturism have added to making non-Western narratives visible (Gaugele and Titton, 2019). In the context of digitisation, fashion has seen a recent and dynamic stream of production in digital fashion, which requires designers and wearers to rethink fashion from more digital perspectives. While there is yet no consensus on the conceptualization of digital fashion, it is clear that the concept is flexibly evolving, including complexities related to bodies and experience (Tepe, 2024), new making processes (Särmäkari, 2023) and the borders between tangible and intangible worlds (Domozlai-Lantner et al., 2024). In addition, as Spicher et al. ((Spicher et al., 2024), p.3) suggest, thinking digital fashion from its various contexts, rather than from a single definition, may help in better grasping the phenomenon. Some of these contexts include computer aided design programmes, artificial intelligence, video games, branded metaverse spaces, virtual reality, augmented reality and avatar mediated environments. These contexts allow for novel professional tracks to be explored and still unforeseen futures of fashion, prompting responses from educational institutions to fashion houses. In addition, and aligned with the interests of this study, digital fashion has been noted as enabling fashion accessibility (Särmäkari, 2023), which may play a role in advancing the decolonization of fashion archives.

A wide range of digital tools is being tested across the fashion sector; Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly generative models, is being integrated at multiple points along the value chain; including design, product development, forecasting, and communication, offering new ways to generate content, streamline processes, and engage with consumers (Rizzi and Casciani, 2024). Within this context, a new designer–AI collaboration space is emerging, shaped by the broader social construction of creativity (Atkinson and Barker, 2023; Rizzi and Bertola, 2025). Brands have invested in Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) collections and immersive virtual stores to construct novel brand experiences and revenue models (Park and Lim, 2023). These initiatives demonstrate how avatars, digital skins, and blockchain-authenticated assets are being leveraged as aesthetic novelties and as tools of self-expression, exclusivity, and community building. Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) are expanding how fashion is experienced, enabling digital try-ons, interactive presentations, and new spatial formats for fashion storytelling (Park and Lim, 2023). This shift is also cultural, as it allows users to engage with fashion in platform-specific ways. These technologies may lay ground to redefine what counts as fashion, who participates in its creation, and how its value is produced and circulated (Sayem, 2022).

Methodology

A set of exploratory research questions were formulated aiming to critically examine the intersections of digital technology, archival practice, and decolonial methodologies within the fashion heritage context. These questions do not seek to test hypotheses, but rather to orient the analysis toward key concerns raised in the literature and the case studies; particularly the need to interrogate how power, visibility, and mediation operate within digitised archival spaces. The questions also reflect the study’s broader commitment to engaging with postphenomenological theory and reflexive, situated methodologies that foreground the researchers’ positionality:

1. Can digital technologies be critically leveraged to decolonise fashion archives and reshape heritage narratives?

2. In what ways do postphenomenological engagements with digital fashion archives mediate users’ understanding of cultural memory and power?

3. How can reflexive methods offer insights into researcher interaction with digitised artefacts, and what epistemic challenges do they surface?

The research systematically follows an exploratory case study (

Yin, 1994) research strategy to investigate the role of digital technologies in decolonising fashion archives. The methodology integrates snowball sampling (

Parker et al., 2019) suited for uncovering underrepresented and emergent initiatives, desktop research, and the researchers’ experiential knowledge (

Nimkulrat et al., 2020) via postphenomenological data collection. Case studies are particularly suitable for exploring real-life phenomena within their contextual environments (

Yin, 1993), making them ideal for studying fashion archives embedded in specific historical, cultural, and institutional contexts (

R and owley, 2002). Exploratory case studies are aimed at identifying emerging patterns, trends, and practices. Meanwhile, descriptive methods provide detailed accounts of specific technologies and methodologies (

Chetty, 1996), ensuring a comprehensive exploration of areas characterised by rapid innovation and fluid boundaries, e.g.: applying digital tools in fashion archives (

Breslin and Buchanan, 2008). An essential advantage of exploratory case studies is their flexibility, crucial for investigating emerging phenomena where research designs must remain open to unexpected findings (

Meyer, 2001). Twenty-two cases were initially collected, categorised, and subjected to a descriptive analysis, where each case was evaluated based on the following criteria:

• Keywords: The thematic goals of the archive, including topic and focus, such as its emphasis on marginalised voices, cultural sustainability, or reimagining archival practices.

• Technologies Employed: Integrating specific digital tools such as NFTs, AR, 3D modelling, or other traditional/digital technologies.

• Specific Relevance Areas: The alignment of the case with the study’s aim to explore decolonial narratives.

• Approach: What strategies are used to address the topics in each of the cases, such as speculative, critical, participatory, educational, and preservation.

This preliminary analysis ensured a broad understanding of how diverse archives engage with digital technologies, laying the foundation for selecting cases. The chosen cases represented varying approaches and innovations while covering three or more areas of specific relevance. The ulterior selection criteria were based on the approach explored in each case, where the general attitude and nature of the case is expressed. From the initial pool, four cases were selected for in-depth exploration. Each case chosen reflects diverse approaches to digital technologies in fashion archival practices, as defined by the research brief. The chosen cases focus on four key approaches: Critical, Speculative, Educative and Heritage.

Selected cases were further investigated under a postphenomenological framework to deepen the exploration of user interactions with digital fashion archives. As a qualitative research approach, postpehnomenology emphasises understanding the lived experiences of individuals as they engage with the phenomena being studied (van Manen, 1990). Central to postphenomenology is the principle of intentionality, which focuses on the subjective relationship between the individual and the object of their experience (Moustakas, 1994), highlighting the importance of real-world engagement in qualitative research (Bloor and Wood, 2006). A postphenomenological lens emphasises the mediating role of digital technologies in shaping human-world relations (Rosenberger and Verbeek, 2015). While rooted in phenomenological traditions that explore lived experience, postphenomenology focuses on how technological artefacts co-constitute understanding and perception, crucial to explore how digital archives frame, constrain, or reconfigure engagements with cultural memory.

In this case, postphenomenology provides a means of capturing the relational and affective dimensions of archival engagement, offering insights into how digital tools mediate users’ interactions with historical and cultural materials. The framework is well-suited to longitudinal qualitative research, allowing for a sustained and iterative examination of experiences over time, uncovering behaviour, perception, and meaning shifts (Saldaña, 2009). Digital tools shape how users perceive, interpret, and engage with archival content, technologies mediate human-world relations by amplifying certain aspects of experience while diminishing others, thus co-constructing the meanings users derive from their interactions (Rosenberger and Verbeek, 2015). This highlights the interplay between human intentionality and technological mediation; for instance, AR might foreground an archive’s specific visual or textual elements while filtering out others, influencing how users emotionally and cognitively connect with the material. Similarly, VR can immerse users in reconstructed historical contexts, reshaping their temporal and spatial perceptions of archival narratives.

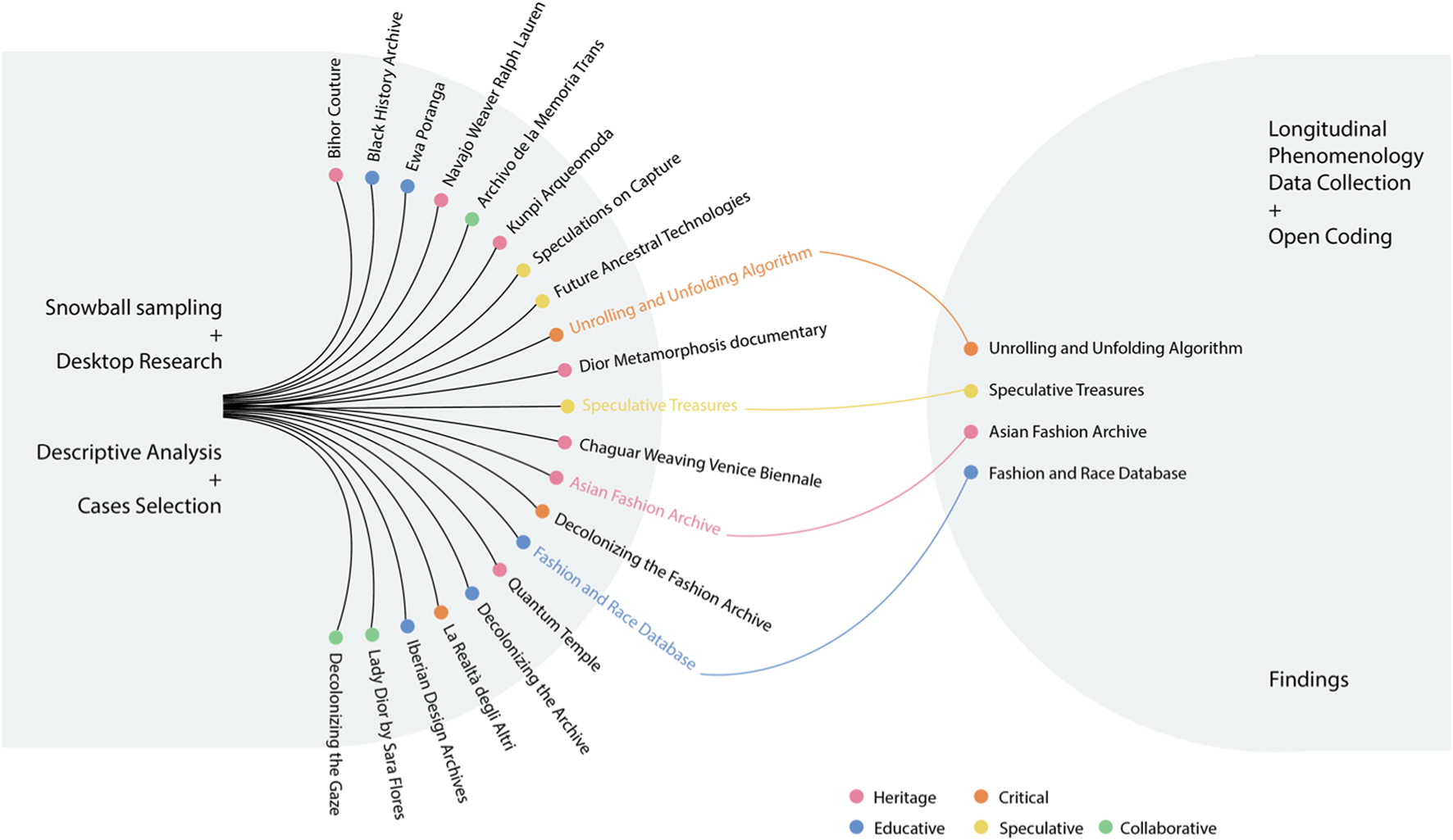

A diary-based reflexive method to document and analyse our own encounters with digital fashion archives was employed. These diary entries captured experiential observations, emotional responses, and interpretive reflections, functioning both as a method of inquiry and a critical tool for unpacking the epistemic dimensions of the case studies. This method allowed for a foregrounded positionality of the researchers, introducing a more sitated and empathic approach when reporting the experience. This two-stage analysis process employed open coding, a qualitative technique that facilitates the identification of patterns and emergent themes. This process, informed by van Manen’s (van Manen, 1990) emphasis on descriptive richness, ensures that the nuances of each interaction are preserved. This longitudinal engagement and iterative analysis are represented as converging towards actionable findings. The research process is illustrated in the following visualisation (Figure 1), highlighting the methodological structure.

FIGURE 1

Visualisation of the methodology from initial sampling to final open coding analysis and findings.

Results

The research has resulted in categorising cases according to their approaches, keywords and technologies employed, supporting the analysis of the initially raised data. From this stage, more clarity surfaced regarding the suitability and relevance of the cases, for example, in terms of how they cover the key areas in the scope of this study: technology, archival practices, fashion and textiles, and heritage. Notably, many cases combined a series of approaches; however, we have used the most prominent ones in the categorisations. In some cases, two approaches were equally relevant and thus added to the analysis. The table below (Table 1) presents all the cases collected and some of the categorisations developed in the study.

TABLE 1

| Case # and name | Keywords | Technology | Approach | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bihor Couture | Cultural appropriation, Fashion, Critical campaign | No digital technology | Heritage |

| 2 | Speculative Treasures | Archive, Coloniality, Speculation, Digital files, Archeology | 3D Scanning, AI, GANs, Videomaking | Speculative |

| 3 | Ewa Poranga | Teaching, Indigenous cultures, fashion histories and practices | Online Education | Educative |

| 4 | Navajo Weaver Ralph Lauren | Indigenous heritage, fashion design | No digital technology | Heritage |

| 5 | Archivo de la Memoria Trans | Queer, collective memory, Latin America | Digital Archive | Participatory |

| 6 | Kunpi Arqueomoda | Indigenous heritage, Arqueomoda, Andean heritage, sustainability | Archaeological data and archives, no digital technology | Heritage |

| 7 | Speculations on Capture | Islamic, archival documents and photographs, fiction, and imperial narratives in museums | 3D modelling, video making | Speculative |

| 8 | Future Ancestral Technologies | Indigenous heritage, futures, costume, speculative fiction | Digital media, textiles, film | Speculative |

| 9 | Unrolling and unfolding algorithms | African crafts, textiles, binary code, dutch wax print | Algorithms, videomaking | Critical |

| 10 | Dior Metamorphosis documentary | ancestral textiles, high-fashion | Film of collection, no digital technologies | Heritage |

| 11 | Black History Archives | technology, teaching, black history, | App/Digital Platform, AR | Educative, Participatory |

| 12 | Chaguar Weaving Venice Biennale | ancestral textiles, cultural heritage, art, community, Indigenous knowledge | No digital technology | Heritage |

| 13 | Decolonising the Gaze | colonial textiles, participatory research, eurocentrism, archives, immigration | No digital technology | Heritage, Participatory |

| 14 | Decolonising the Fashion Archive | Indigenous representation, cultural recovery | Digital Archive | Critical, Heritage |

| 15 | Fashion and Race Database | Education, database, fashion and race | Online Database | Educative |

| 16 | Quantum Temple | digital tourism, cultural expressions, immersive experiences | Blockchain, NFTs | Heritage |

| 17 | Decolonising the Archive | Pan-African heritage, community, theatre | Online Platform | Heritage, Educative |

| 18 | La Realtà degli Altri | Epistemological violence, art, | No digital technology | Critical |

| 19 | Iberian Design Archives | design, tradition | Digital Archive | Heritage, Educative |

| 20 | Lady Dior by Sara Flores | high fashion, cultural appropriation, heritage | No digital technology | Collaborative, Heritage |

| 21 | Asian Fashion Archive | fashion, diaspora, heritage | Digital repository | Heritage |

Summary of exploratory cases and their categorisation. Selected cases are identified with a grey background highlight.

Following the initial descriptive analysis, four cases were selected based on criteria of diversity and relevance. Cases without use of digital technology were removed, and remaining cases were analysed in regard to the technologies employed, the cultural representation proposed, and the creators’ response to contacts by the authors through existing contacts on digital resources. Through this analysis we expected to cover with breadth the landscape raised through the sampling, which enabled a broader understanding of the context. The final selection brings examples from the various approaches identified, and cover initiatives that engage directly with notions of decolonial thinking from African, Asian, and South American perspectives. The sections below introduce the cases based on phenomenological data collection.

Case 2: speculative treasures by juan covelli

Juan Covelli is a Bogotá-based artist and curator; he identifies himself as a visual artist using digital media, technology, and archives as creative tools; “I like to revisit colonial histories, to look at the past to generate ideas for the future, exploring different possibilities for futures that don’t align with the linear narratives we are historically used to.” When describing his practice, he answers “almost everything I do is installation work that collapses this digital aesthetics intending to subvert those colonial histories”.1 In Speculative Treasures, created between 2020 and 2024, Covelli exemplifies his use of technology to critique colonial histories and rethink the function of archives. The project focuses on the Quimbaya Treasure, a collection of pre-Columbian artefacts housed outside Colombia, framed as displaced heritage (Covelli, 2022a).

Using Generative Adversarial Networks2 (GANs), Covelli trained AI algorithms on 2D images of these artefacts from the Gold Museum of Bogotá [Museo del Oro del Banco de la República] database, enabling the generation of 3D representations of artifacts from the Quimbayá treasure that are kept at the Museum of the Americas [Museo de América] in Spain, enabling their speculative repatriation (Covelli, 2022b). Among the artefacts presented, we find a digitally reconstructed pendant (Figure 2) that expresses body adornment as a universal and historical practice that reconnects contemporary fashion with ancestral knowledge systems. This reinterpretation challenges the Eurocentric framework that separates fashion from tradition, relegating non-Western dress to the margins as non-fashion (Jansen, 2020). Body adornment serves as a crucial element in communicating identity, status, and cultural narratives that connect the wearer to their community, history, and heritage (Cappellieri, 2014)

FIGURE 2

Pendant from Tesoros Especulativos [Speculative Treasures]. Video still, Juan Covelli, 2020–2022. Screenshot from Covelli, J. [@juan_covelli].

‘I visited the Museo del Oro on my first trip to Bogotá, and this piece fits perfectly with the ones exhibited. The speculative approach feels akin to world-building. The repetition of the video is mesmerising, each loop revealing a fragment I had not seen before.’ (Diary note Author1, 2025)

The work critiques Western museums’ empirical and extractive methods by deconstructing their colonial framing and exclusionary practices. Covelli sustains, “every time someone goes to a museum and sees these objects, in the end, they also see colonial history since the museum is a colonial space”. The installation includes 12-channel video outputs (Covelli, 2022c), all of which highlight the biases present in existing archives and the possibilities of creating new narratives through speculative archaeology. Covelli’s methodology involves reimagining cultural objects using 3D scanning and coding, challenging the authority of traditional archival practices while engaging the viewer in the politics of heritage.

‘Is using archives to produce possible (and inexistent in the physical world for all we know) archives a speculative aspect or a paradox?’ (Diary note Author1, 2025)

Using the referenced technologies, Covelli subverts narratives perpetuated by traditional archives, transforming them into interpretive spaces. This offers a technological counterpoint to extractive practices that define colonial histories, illustrating how digital tools can enable alternative narratives. The project underscores the importance of interrogating the power dynamics within archives, mainly how objects are represented and accessed, engaging with broader questions of ownership and restitution.

Case 9: unrolling unfolding algorithms by ibiye camp

Ibiye Camp is an interdisciplinary artist, architect, researcher, and designer whose work intersects architecture, technology, and postcolonial studies. Her practice explores postcolonial subjects and technology in the built environment, using tools such as sound, video, augmented reality, and 3D objects to interrogate biases and conflicts inherent in digital infrastructure. Camp’s experiences as a British Nigerian navigating multiple artistic, geographic, and institutional spaces shape her perspective, emphasising multiculturalism and spatial justice (Ibiye Camp, 2025; Das, 2025).

‘At first, it is disorienting—clearly an artistic expression. The background sound pulls me in; I close my eyes and find myself transported through bustling streets. I picture woven figures and structures of vivid textiles.’ (Diary note Author1, 2025)

Unrolling and unfolding algorithms is a video essay (see video still in Figure 3) by Ibiye Camp that examines the transformation of African textiles and their cultural significance. Featured in CIRCLE, a digital think-tank by 2050.plus and Slam Jam (Slam Jam, 2021), the project focuses on injiri, a Southern Nigerian cloth traditionally crafted by Kalabari3 women. Historically, injiri was produced by manually altering imported Madras4 cloth through the meticulous process of pele terpite (cut thread),5 in which craftswomen used needles and razor blades to create geometric openwork patterns, embedding knowledge systems akin to binary code (Camp, 2021). Industrialisation has since replaced these manual methods with mechanised production, disrupting both the textile’s authenticity and the socio-economic structures of its makers. Camp extends this critique to Dutch wax print, a mass-produced textile that mimics traditional batik while contributing to the displacement of indigenous African textiles in the globalised economy, underscoring the broader erasure of local crafts and cultural heritage (Camp, 2021).

FIGURE 3

Unrolling and unfolding algorithms video still, 2021. Screenshot from 2050+ [Vimeo].

‘The zoomed-in shots allow me to grasp the intricacy of the work. I try to imagine the documentation, scanning, and 3D modelling process that gives form to these textiles and figures. It is only when I read the description that the depth of the project clicks, the poetic parallelism between algorithms and the analogue patterns in the fabric. Hypnotic.’ (Diary note Author1, 2025)

Camp’s project situates injiri within discussions of algorithms, postcolonial history, and technology. Camp highlights digital and analogue patterns embedded in African fabrics by interpreting the textile through a technological lens. Her work explores reclaiming these textiles and their histories, reimagining material culture amid mass production and globalisation. Unrolling and unfolding algorithm intersects cultural heritage, technology, and postcolonial critique. By framing injiri through algorithms, Camp challenges Western narratives that commodify African textiles, envisioning a digital archive that preserves weaving techniques displaced by mechanisation.

‘This video allows the viewer to navigate, to wander as if within a dream.’ (Diary note Author1, 2025)

Case 15: the fashion and race database

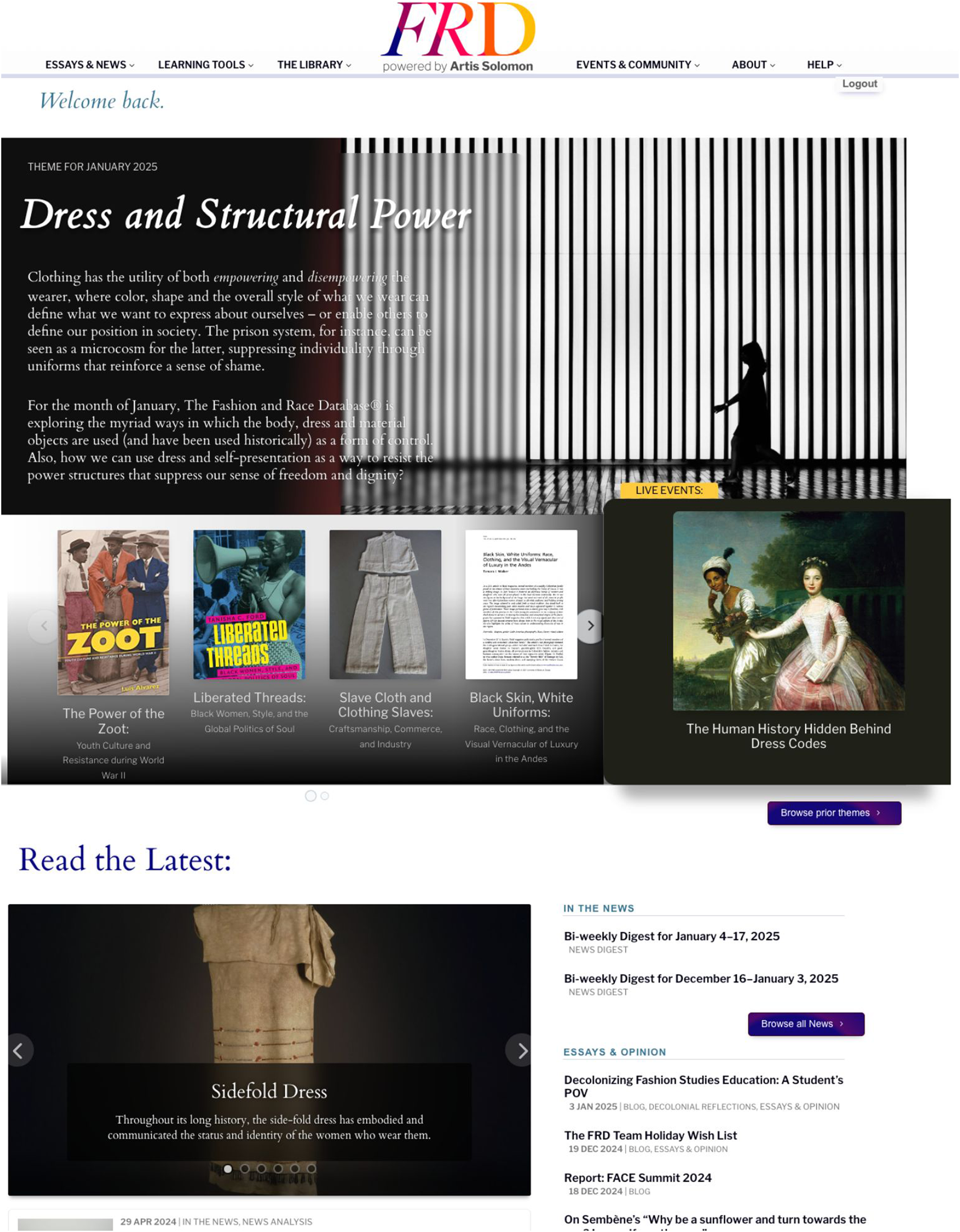

Founded to de-centre fashion narratives and histories (pl.), The Fashion and Race Database (FRD) provides its audience with an extensive archive of publications, events, podcasts, and news. Largely critical of the white, global north narratives dominating the historical accounts of fashion, the platform seeks to diversify perspectives by bringing narratives from various ethnic backgrounds, such as Black, Asian, Latin American and various Indigenous groups. Founded by anthropology researcher Kim Jenkins in the mid-2010s (Snelg and rove, 2025), FRD is today a well-established space for discussion around fashion. It profoundly engages with discourses in cultural heritage, justice, and decoloniality, amongst others. Several collaborators contribute with essays, articles and podcasts to cover such a broad outlook. In addition, they also have services such as a job ads platform and curated events suggestions.

The material is generally organised around types of content (see Figure 4), with sections including “In the News,” “Objects that Matter,” “Essays,” and “Reviews” (FRD, 2025). Monthly themes add a curatorial dimension to the platform, where themed essays are accompanied by literature suggestions and a downloadable “Learning Guide,” which guides readers towards further exploring the themes.

FIGURE 4

A screenshot from the landing page of the Fashion and Race Database.

From the phenomenological experience, the platform gives a sense of making justice as one begins to uncover topics that have long been left shadowed by the normative and colonialist Global North discourse. To look at fashion beyond the catwalks, lifestyle magazines, and shopping streets of Milan, Paris, London, and New York adds a sigh of relief–after all, fashion is made globally. Including Indigenous perspectives contributes to sharing that Indigenous knowledge is contemporary and in constant development, just as any other form of knowledge (Lyons, 2011).

Navigating the platform was not always straightforward forward, and at times, returning to a previously found page was difficult, such as a list of collaborators not present in the main page menu or website map.

‘I'd like to go back to the collaborators' page. Not sure how I got there. The last material [read] seems to come from the same collaborators. Would be nice to read from others.’ (Diary note Author2, 2025)

Currently, most of the platform’s content is behind paywalls, which seek to cover the costs of running the platform and support collaborators fairly. FRD relies solely on suscripion fees to support their opperations but they still run a sale a couple of times a year, offering lower prices to subscriptions. The inability to access some content added a negative dimension to the overall experience. In addition, more clarity would be recommended on how the different content is made available and what bases the choice between open and paywalled access. This practice could have a political dimension, which would be great to express clearly.

‘[…] it is unclear what I can actually access on the website, and it keeps taking me back to the 'Become a Member' page. Could there be open access material, e.g. if collaborators produce the content without a fee?' (Diary note Author2, 2025)

Regarding the technology explored, the platform uses more traditional media, such as the website itself, in addition to downloadable PDFs and links to other content and events, both digital and physical (mostly in the USA). One good experience was the addition of podcasts to the otherwise traditional textual content, which made it feel like the FRD extends beyond its worldwide web address. With eight episodes currently available, each about 30 min long, the podcasts focus more on black fashion narratives and are an excellent addition that speaks to a broader audience.

Case 21: Asian fashion archive

The Asian Fashion Archive (AFA) is a platform built in 2020 to communicate about the richness of Asian cultures in the context of fashion. The website appeals to a sense of community as it responds to the anti-Asian hate crimes which emerged in the USA during the COVID-19 pandemic (AFA, 2025). Even though racism against people of Asian descent in the USA has existed since the 1700s, the pandemic served as hate encouragement, leading to crimes (Gover et al., 2020). In response, counter-speech and activities arose, often promoting non-violent acts and community support (He et al., 2022), such as the AFA.

Faith Cooper, Asian studies researcher and the founder of the platform states that “[t]he Asian Fashion Archive is more than a digital humanities project, but has grown to be a community where like-minded individuals can come together to share a passion for Asian culture and fashion” (AFA, 2025). On its page (Figure 5), the AFA invites the broader community to contribute by indicating sources to enrich the content on the platform. However, from the content accessed, there is no reference to collaborators, which indicates that the great majority of content has been produced by the founder themselves.

FIGURE 5

The landing page on the Asian Fashion Archive website.

AFA works as a repository with links to external sources categorised into “Films & Clips,” “Museums & Exhibitions,” “Podcasts” and “Publications & Articles.” In addition, the AFA holds a section for younger audiences, including videos, and a section for educators, which has extensive teaching guides and platforms. Apart from managing its website, AFA maintains an Instagram account, focusing on visual research related to Asian culture and historical photography. No content is produced specially for AFA, leaving much of the interpretation and production of discourse to the reader. Conclusively, the platform does not pose as a critical voice but as a source of information for the broader public and identification for Asian communities.

The website includes a “Search by Region” function, which guides visitors through resources of particular regions in Asia and can work as an excellent tool for researchers focused on a specific Asian cultural expression. The navigation on the platform is uncomplicated and built on a simple structure. In addition, the language used is highly approachable to many, and content curation pays special attention to popular material, such as open-access YouTube videos, popular magazines, and podcasts.

The large and easily accessible audio-visual repository appeals to the general public, driving curiosity with quick responses. Unlike other links in the repository, videos are embedded in the website, making navigation across content efficient and easy and retaining visitors for long periods of time.

‘I have just spent a long time going through the video content, many of which follow craftspeople in the making of traditional clothing and artefacts' (Diary note, Author 2, 2025)

Accessibility to a larger audience is also present in the effort of keeping an active Instagram account, with currently 17.8k followers (@asianfashionarchive, 2025), making it a working strategy to gather followers and improve the platform’s visibility. In the context of the Instagram account, collaborators share their personal archives, including family pictures. This supports the community-building aspect of the platform in a similar way to personal Instagram accounts. The popularisation approach is probably one of the reasons why a more critical or academic tone is not found in AFA, resonating with the overall positive counter-hate-speech movement that the page aligns with.

Analysing the findings

The table below (Table 2) summarises the selected cases, providing an overview of their roles in contemporary archiving practices in fashion and textiles. These selected cases exemplify diverse modes of engagement with digital fashion archives, distinguishing between archival platforms or repositories (FRD, Asian Fashion Archive) and projects creating and/or working with archival material (Speculative Treasures, unrolling and unfolding algorithm). While the database and repository prioritise educational and heritage-oriented approaches, the more artistic projects take speculative and critical stances, highlighting the multiplicity of archival engagement strategies. This depends on how archives manifest as “extremely large assemblages” (15, p.20) shaped by their objectives, formats, technologies, audiences, and archivists.

TABLE 2

| Date | Case # & Title | Author(s) | Keywords | Technologies | Brief analysis | Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020–2022 | 2. Speculative Treasures | Juan Covelli | Archive, Coloniality, Speculation, Digital files, Archeology | 3D Scanning, AI, GANs, Videomaking | Critiques colonial histories while proposing alternative representations, centring the Global South’s perspective | Speculative |

| 2021 | 9. Unrolling and unfolding algorithms | Ibiye Camp | African crafts, textiles, binary code, dutch wax print | Algorithms, videomaking | Reimagines materiality and labour through digital and traditional intersections. Creating a digital archive for weaving techniques that have been replaced by mechanisms | Critical |

| 2017— | 15. Fashion and Race Database | Kim Jenkins (founder), Various Contributors | Education, database, fashion and race | Online Database | Centres histories and contributions of minority groups in fashion through broad collaboration with content creators. The database raises awareness of the shadows placed on non-white cultural expressions, especially within fashion | Educative |

| 2021— | 21. Asian Fashion Archive | Faith Cooper | fashion, diaspora, heritage | Digital repository | Open access resource to explore Asian fashion through direct links to videos, exhibitions, podcasts and publications. Brings together both traditional media (such as magazines or museums) and contemporary media (podcasts, websites, social media) | Heritage |

Summary and details of selected cases and their perceived approaches.

Speculative Treasures and Unrolling and unfolding algorithms emphasise the creative possibilities enabled by digitisation. Covelli and Camp employ AI, 3D scanning and modelling, and video-making to experiment with archival reinterpretation, demonstrating how computational tools generate new insights without disrupting the material or symbolic order of the original archives (Ernst, 2016). The use of speculative methods to engage with archives emphasizes the use of imagination as a tool for resistance and archival reinvention, similar to how Afrofuturism is used as a strategy where imagination becomes method and message in the communication of diasporic stories and traditions (Eismann et al., 2019). By contrast, archival platforms that do not have an explicit critical approach, like the Asian Fashion Archive, rely on social media and visual resources to maximise accessibility and audience engagement. While these approaches enable knowledge transmission and reduce the threshold for users to familiarise themselves with diverse cultures and their heritage, we ask ourselves if this could risk “othering” non-Western traditions through a voyeuristic gaze, a question that warrants further investigation. In these cases which leverage on digital infrastructure, digital fashion archives act as metamediums; they are not merely storing or displaying garments but reshaping how fashion knowledge is produced, accessed, and experienced (Vacca et al., 2023), in doing so they challenge the authority of traditional curatorial gatekeeping.

Across the selected cases, there is an evident expansion of available materials documenting non-Western fashion narratives. These contribute to deconstructing Eurocentric archival hierarchies, aligning with broader trends towards amplifying knowledge production by marginalised voices (L'Internationale, 2016). Acknowledging the role of archives as sites of power and epistemic production that shape what is visible and preserved, all cases evidenced that archives could be understood beyond custodial spaces. These are defined as active spaces of epistemic struggle (Caswell and Cifor, 2016), or participatory and bottom-up proposals (Martin and Vacca, 2018). However, accessibility remains a challenge. Paywalls, as seen in the FRD, restrict access, constraining an open engagement that could bring critical and well-articulated viewpoints. This raises issues about how economic barriers shape the circulation of decolonial discourse and even cultural and heritage assets. Offering free access to low-income users could be a strategy to address this limitation. Digital literacy also emerges as a critical factor in audience engagement. While digital archives create an illusion of transparency intrinsic to the neutral perception of technology and data (Joyce et al., 2021), they may facilitate broader participation (including more stakeholders such as a wider audience, researchers, educators, students, etc.) or alienate users unfamiliar with digital tools. As archives increasingly emphasise accessibility, it is crucial to assess whether digitisation enables inclusion or reinforces these digital divides (L'Internationale, 2016). Social media and podcasts, as seen in the Asian Fashion Archive and Fashion and Race Database, provide more approachable formats that cater to younger audiences, supporting dissemination. However, these digital assets are inherently volatile, prone to manipulation, misinterpretation, and technological obsolescence, necessitating ongoing strategies for digital preservation (Schnapp, 2016).

Overall, the cases highlight the affordances and limitations of digital archives in engaging with fashion histories beyond the Global North. These case studies contest the fashion system’s Eurocentric canon by foregrounding localised and diasporic knowledges, what Jansen (Jansen, 2020) identifies as a necessary disinvestment from modernity’s phantasmagoria. While computational tools offer new ways to navigate archival material, and online platforms foster visibility, the structural inequalities embedded in digital infrastructures remain a critical concern. Addressing these challenges (e.g. access, interpretation, technological literacy) requires a continued interrogation of how technology mediates archival practices and shapes the narratives that emerge from them, especially since digital conservation methods are still in their early stages, with the oldest surviving digital files being less than 50 years old (Schnapp, 2016).

Across the four case studies, the findings suggest that digital archiving practices in fashion are being reconfigured as spaces of critical and speculative engagement. These initiatives use digital tools not simply for preservation but to imagine new archival futures, ones that resist dominant histories, expose structural exclusions, and foreground alternative narratives. By centring underrepresented makers, diasporic knowledge systems, and collaborative authorship, the projects cultivate a heightened awareness of how institutional power shapes cultural memory. At the same time, they propose digital infrastructures, databases, repositories, AI renderings, as tools for expanding accessibility, particularly for communities in the Global South. Together, they demonstrate that digital fashion archives can operate as platforms for epistemic intervention: challenging what counts as fashion heritage and who gets to define it.

Discussion

In response to the first research question: Can digital technologies be critically leveraged to decolonise fashion archives and reshape heritage narratives? this study demonstrates that when paired with intentional epistemic repositioning, digital experiences can disrupt exclusionary archival structures. The case studies reveal how cultural institutions and grassroots initiatives are using digital tools, such as interactive platforms, open-access databases, and metadata reclassification, to make space for marginalized narratives. This aligns with critiques from Jansen (2020) and Eismann et al. (2019), who call for a redefinition of fashion’s ontological scope beyond Eurocentric modernity.

The second question: In what ways do postphenomenological engagements with digital fashion archives mediate users’ understanding of cultural memory and power? Is addressed through the analysis of how users interact with digital interfaces and archival infrastructures. Drawing on postphenomenology, the study shows that technologies are not neutral conduits but active mediators that co-shape perception, attention, and meaning making. For instance, the structuring of search filters, the presence or absence of provenance metadata, and the design of exhibition pathways each guide users toward certain ways of interaction. The digital archive, then, becomes a contested space where archival authority is negotiated through both technological affordances and user interpretation, foregrounding the need for critical interface design.

Finally, the third question: How can reflexive methods offer insights into researcher interaction with digitised artefacts, and what epistemic challenges do they surface? Underscores the methodological intervention of this paper. As noted in the methodology section, diary writing helped trace affective, sensory, and situated responses to the engagements with the case studies. This method allowed the researchers to observe the technological mediation while documenting the embodied tensions, engaging with fashion heritage shaped by histories of extraction, appropriation, or absence. This reflexive layer enriched the interpretive depth while surfacing considerations around access and representation, core concerns for any decolonial archival praxis.

The decolonisation of archives may be understood as operating on two levels: challenging the commodification of the archive (capitalising it, evidenced by the growing trend in the ownership of private archives) and the unmasking of supposedly neutral criteria of classification used as an instrument of imperial control (L'Internationale, 2016). Traditional archives have long functioned as sites of knowledge production that affirm dominant narratives, often reinforcing colonial power structures. However, contemporary digital archives that have expanded beyond their traditional roles, incorporating diverse materials, digital surrogates, and extensive metadata to enhance accessibility and engagement (Schnapp, 2016) offer opportunities to subvert and resist these frameworks by promoting accessibility, inclusivity, and alternative epistemologies (L'Internationale, 2016). While this transition has led to significant advancements, it introduces new complexities, such as digital divide issues, metadata biases, and the challenge of maintaining digital records over time (Schnapp, 2016). Modern archives have expanded beyond traditional roles, incorporating diverse materials, digital surrogates, and extensive metadata to enhance accessibility and engagement. These transformations challenge conventional archival models, necessitating new processing, conservation, and cataloguing approaches. Rather than treating cultural objects as isolated entities, archives are increasingly understood as networks of relationships, allowing for more fluid and adaptable frameworks. This shift also emphasises outreach to underrepresented audiences and the development of innovative search and retrieval systems that move beyond static institutional structures (Schnapp, 2016).

Fashion archives present a paradox: while archives are traditionally understood as heritage and historical repositories, fashion is defined by its connection to the present, driven by cycles of reinvention and change (Eismann et al., 2019). The dominant Western definition of fashion as a continuous shift in styles contrasts with the static categorisation of non-Western dress traditions, often framed as timeless or unchanging (or non-fashion) (Jansen, 2020). Beyond historical restitution, digital fashion archives offer significant implications for contemporary fashion production, particularly for designers and creative directors. Fashion professionals frequently turn to archives as inspiration for new collections (Almond, 2020). By expanding access to archival materials and diversifying the narratives they contain, digital archives can contribute to a design process under a decolonial lens. However, the decolonisation of archives alone is insufficient; the way designers engage with archival materials must also be critically reassessed–interrogating provenance, context, and embedded biases could enable designers to approach archival materials with greater awareness of their cultural significance. Digital fashion archives also enable new classification systems that move beyond text-based documentation, incorporating sensory dimensions crucial to fashion, such as movement, texture, and tactility. This is particularly relevant given that fashion is experienced visually and through material interaction and bodily engagement. Digital technologies such as 3D modelling, AR, and haptic interfaces offer possibilities for archiving fashion in ways that honour its multisensory nature. These advancements could support a more holistic understanding of fashion heritage, ensuring that knowledge systems embedded in textiles, craftsmanship, and embodied practices are preserved and made accessible in ways that resist static, Eurocentric definitions of fashion. However, these advancements are still at a nascent stage and have not yet been fully explored in the context of digital archives.

The notion of temporality is central to discussions of decolonial archives. Decolonial frameworks seek to challenge the historical erasure of non-Western cultures, recognising them as holders of the past and as active producers of knowledge and technological futures (Lyons, 2011; Mbembe, 2015). Ernst (Ernst, 2016) suggests that archives should not be understood as fixed repositories but as dynamic, multi-temporal constructs that evolve alongside technological and epistemological shifts. Digital archives, in particular, operate within an “archive in motion” paradigm, where constant updates, interactions, and real-time engagement redefine the very archival temporality, “[t]he archive loses its temporal exclusivity as a space remote from the immediate present.” (4, p.14). In this scenario, the traditional separation between the past and present dissolves, allowing archives to function as living entities that continuously reshape historical narratives. Mbembe (Mbembe, 2015) further critiques the colonial imposition of linear time, which positioned Indigenous peoples as “outside of time” and incapable of historical agency, reinforcing their exclusion from dominant archival frameworks.

Several scholars propose alternative models for rethinking digital archives through a decolonial lens. Caswell and Cifor (Caswell and Cifor, 2016) advocate for a feminist ethics of care (Tronto, 1993) in archival practice, emphasising relationality, empathy, and responsibility over rigid institutional structures. They argue that digitisation should not merely replicate archival inequities but foster ongoing relationships between archivists, record creators, and users, actively addressing structural imbalances. “Archivists need a feminist care web of assessment that values emotions and relationships, that provides a more holistic view of our impact.” (Caswell, 2024). Fraser and Todd (Frase et al., 2016) propose a specific perspective on the decolonisation of Canadian archives, suggesting these can only ever be partial due to their inherently colonial foundations. Rather than attempting to decolonise these institutions fully, they advocate for a critical decolonial sensibility that acknowledges their historical biases. Decolonisation, they argue, requires context-specific approaches that engage with legal, political, and historical realities while expanding archival collections to include diverse oral histories, which are vital for centring Indigenous voices and narratives within archival spaces (Frase et al., 2016). Afrofuturism has also become a potent strategy for unsettling colonial temporalities within fashion archives. Eismann (Eismann et al., 2019) argues that Afrofuturist fashion disrupts Western-centric fashion archives by challenging linear time and rigid classifications. By embracing speculative approaches that blur the boundaries between past, present, and future, Afrofuturist frameworks offer a means of decolonising the content of archives and their very structure and function.

The transition to digital archives has the potential to democratise access to historical materials and disrupt conventional power structures. As Ernst ((Ernst, 2016), p.15) notes, making archives electronically accessible challenges their traditional authority, allowing for broader engagement and critique, [b]y becoming electronically-accessible “online”, the archive is being deprived of its traditional power.” Nevertheless, “archives are not just static entities perceived simply as an assemblage of hybrid materials. Other forms of immaterial memory storage exist, such as oral histories including narratives, experiences and feelings.” (Kolb and Kothe, 2024). They also remain shaped by the infrastructures that govern them. Kolb and Kothe (Kolb and Kothe, 2024) remind us that archives are active agents in producing social memory, determining what is preserved, omitted, or rendered inaccessible. Addressing these issues requires a critical engagement with digital methodologies, ensuring that archives remain sites of contestation rather than static repositories. In this context, Koh (Koh, 2012) emphasises that decolonial archives must not only serve as counter-archives to dominant histories but must also interrogate the very notion of what constitutes an archive. This involves questioning established archival hierarchies and embracing alternative modes of preservation that reflect the epistemologies of historically marginalised communities (Eismann et al., 2019). Ultimately, the future of digital fashion archives lies in their ability to foster critical engagement, participatory knowledge production, and the continual redefinition of archival temporality.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI has been used to revise syntax, grammar, and spelling from certain passages to ensure clarity.

Footnotes

1.^These quotes are taken from an interview to the artist, conducted by one of the researchers in 2023 in the context of another research project involving Design Futures and Decoloniality.

2.^GANs are a class of machine learning frameworks widely used in generative artificial intelligence. GANs work through the interaction of two neural networks: a generator that creates data instances resembling the training data, and a discriminator that evaluates these instances for authenticity. The generator aims to produce realistic outputs to “fool” the discriminator, while the discriminator learns to distinguish genuine data from the generated ones. This adversarial process fosters high-quality, realistic data generation. (Generative adversarial network, 2025; Google Developers, 2025).

3.^Kalabari people live along the eastern Niger Delta (Horton, 1962).

4.^Madras cloth is a lightweight cotton fabric originally woven in South India and characterized by its bright, colorful plaid or striped patterns. Historically, it was an important trade item within the British and French empires, often used as barter currency in the transatlantic slave trade. While it became integrated into Caribbean traditional dress, particularly among enslaved and free communities, madras cloth was also appropriated into European fashion during the late 18th century (Rauser, 2020).

5.^For more information on Kalabari textile practices see (Erekosima and Eicher, 1981).

References

1

@asianfashionarchive (2025). Asian fashion archives Instagram profile. Available online at: https://www.instagram.com/asianfashionarchive/ (Accessed January 26, 2025).

2

AFA (2025). Asian fashion archives. Available online at: https://www.asianfashionarchive.com/home (Accessed January 26, 2025).

3

AlmondK. (2020). Disrupting the fashion archive: the serendipity of manufacturing mistakes. Fash. Pract.12 (1), 78–101. 10.1080/17569370.2019.1658346

4

AtkinsonD. P.BarkerD. R. (2023). AI and the social construction of creativity. Convergence Int. J. Res. into New Media Technol.29 (4), 1054–1069. 10.1177/13548565231187730

5

Beltrán-RubioL. (2020). Una historia de la moda en los museos. Culturas de Moda. Available online at: https://culturasdemoda.com/una-historia-de-la-moda-en-los-museos/ (Accessed January 26, 2025).

6

BloorM.WoodF. (2006). Keywords in qualitative methods: a vocabulary of research concepts. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

7

BreslinM.BuchananR. (2008). On the case study method of research and teaching in design. Des. Issues24 (1), 36–40. 10.1162/desi.2008.24.1.36

8

CampI. (2021). Unrolling and unfolding algorithms. Vimeo. Available online at: https://vimeo.com/522733088/06028177fb?login=true&turnstile=0 (Accessed January 26, 2025).

9

CappellieriA. (2014). Sentimental Jewellery [Gioielli Sentimentali]. Venezia, Italy: Marsilio Editori.

10

CaswellM. (2024). Digital feminist care ethics: assessing the web of archival relationships. Brand New Life. 10.5281/zenodo.13947485

11

CaswellM.CiforM. (2016). From human rights to feminist ethics: radical empathy in the archives. Spring81, 23–43. Available online at: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/687705.

12

ChettyS. (1996). The case study method for research in small-and medium-sized firms. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrepreneursh.15 (4), 73–85. 10.1177/0266242696151005

13

CovelliJ. (2022a). Este año terminé la primera fase de mi proyecto Tesoros Especulativos. Instagram. Available online at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CmjpDtsuky9/?img_index=1 (Accessed January 26, 2025).

14

CovelliJ. (2022b). Tesoro especulativo (entrenamiento 2) NFT 2021. Instagram. Available online at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CbvGP_DFYAp/?img_index=1 (Accessed January 26, 2025).

15

CovelliJ. (2022c). I'm thrilled to announce that my project Speculative Treasures (2020-2022) is now part of the Art Collection of the Museo de Arte del Banco de la República, Colombia. Instagram. Available online at: https://www.instagram.com/p/Cmoi_N-uiuW/?img_index=1 (Accessed January 26, 2025).

16

DasJ. (2025). Interview with ibiye camp: data. Future, Public Space. Pin-Up Mag.Available online at: https://archive.pinupmagazine.org/articles/interview-ibiye-camp-data-future-public-space (Accessed August 5, 2025).

17

Domozlai-LantnerD. (2024). “A history of digital fashion: critical theories and turning points,” in Digital fashion: theory, practice, implications. Editors SpicherM. R.BernatS. E.Domozlai-LantnerD. (London: Bloomsbury Publishing), 19–42.

18

EismannS. (2019). “Afrofuturism as a strategy for decolonising global fashion archive,” in Fashion and postcolonial critique. Editors GaugeleE.TittonM. (Berlin, Germany: Sternberg Press), 65–73.

19

ErekosimaT. V.EicherJ. B. (1981). Kalabari cut-thread and pulled-thread cloth. Afr. Arts14 (2), 48–87. 10.2307/3335728

20

ErnstW. (2016). “Radically DDe-Historicisingthe archive,” in Decolonising archives (L’Internationale Online).

21

FeatherstoneM. (2006). Archive. Theory, Cult. & Soc.23 (2-3), 591–596. 10.1177/0263276406023002106

22

FraserN.ToddZ. (2016). Decolonising archives. L’Internationale Online.

23

FRD (2025). The fashion and race database. Available online at: https://fashionandrace.org/database/ (Accessed January 26, 2025).

24

GaugeleE.TittonM. (2019). Fashion and postcolonial critique. Vienna: Sternberg Press.

25

Generative adversarial network. (2025). Generative adversarial network. Wikipedia. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generative_adversarial_network (Accessed January 26, 2025).

26

Google Developers (2025). GANs: generative adversarial networks. Available online at: https://developers.google.com/machine-learning/gan (Accessed January 26, 2025).

27

GoverA. R.HarperS. B.LangtonL. (2020). Anti-asian hate crime during the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring the reproduction of inequality. Am. J. Crim. Justice45 (4), 647–667. 10.1007/s12103-020-09545-1

28

GreggE. (2022). The story of Nigeria's stolen Benin bronzes, and the London museum returning them. Natl. Geogr. Available online at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/nigeria-stolen-benin-bronzes-london-museum (Accessed January 26, 2025).

29

HeB.ZiemsC.SoniS.RamakrishnanN.YangD.KumarS. (2022). “Racism is a virus: anti-asian hate and counter-speech in social media during the COVID-19 crisis,” in Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM international conference on advances in social networks analysis and mining (ASONAM '21) (Athens, Greece: Association for Computing Machinery), 90–94.

30

HortonR. (1962). The kalabari world-view: an outline and interpretation. Africa32 (3), 197–220. 10.2307/1157540

31

Ibiye Camp (2025). INFO + HELLO. Available online at: https://ibiyecamp.com/INFO-HELLO (Accessed January 26, 2025).

32

Indigenousfashionarts (2025). Indigenous fashion arts. Available online at: https://indigenousfashionarts.com/ (Accessed January 26, 2025).

33

JansenM. A. (2020). Fashion and the phantasmagoria of modernity: an introduction to decolonial fashion discourse. Fash. Theory24 (6), 815–836. 10.1080/1362704X.2020.1802098

34

JoyceK.Smith-DoerrL.AlegriaS.BellS.CruzT.HoffmanS. G.et al (2021). Toward a sociology of artificial intelligence: a call for research on inequalities and structural change. Socius Sociol. Res. a Dyn. World7, 2378023121999581. 10.1177/2378023121999581

35

KohA. (2012). Addressing archival silence on 19th century colonialism—part 2: creating a nineteenth Century' Postcolonial' archive. Adeline Koh Blog. Available online at: https://web.archive.org/web/20170816162333/http://www.adelinekoh.org/blog/2012/03/04/addressing-archival-silence-on-19th-century-colonialism-part-2-creating-a-nineteenth-century-postcolonial-archive/ (Accessed January 26, 2025).

36

KolbL.KotheL. (2024). Working with and against the archive. Brand New Life. Available online at: https://brand-new-life.org/b-n-l/focus/working-with-and-against-the-archive (Accessed January 26, 2025).

37

L'Internationale (2016). “Introduction,” in Decolonising archives (L’Internationale Online), 5–8.

38

LyonsS. R. (2011). Actually existing Indian nations: modernity, diversity, and the future of native American studies. Am. Indian Q.35 (3), 294–312. 10.1353/aiq.2011.a447048

39

MartinM.VaccaF. (2018). Heritage narratives in the digital era: how digital technologies have improved approaches and tools for fashion know-how, traditions, and memories. Res. J. Text. Appar.22 (4), 335–351. 10.1108/RJTA-02-2018-0015

40

MbembeA. (2015). Decolonizing knowledge and the question of the archive [lecture]. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand.

41

MeyerC. B. (2001). A case in case study methodology. Field Methods13 (4), 329–352. 10.1177/1525822x0101300402

42

MoustakasC. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

43

NimkulratN.GrothC.TomicoO.Valle-NoronhaJ. (2020). Knowing together–experiential knowledge and collaboration. CoDesign16 (4), 267–273. 10.1080/15710882.2020.1823995

44

ParkH.LimR. E. (2023). Fashion and the metaverse: clarifying the domain and establishing a research agenda. J. Retail. Consumer Serv.74 (September), 103413. 10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103413

45

ParkerC.ScottS.GeddesA. (2019). Snowball sampling. SAGE Res Methods Found Thousand Oaks, California:. 10.4135/9781526421036

46

PecorariM. (2019). Fashion archives, museums and collections in the age of the digital. Crit. Stud. Fash. & Beauty10 (1), 3–29. 10.1386/csfb.10.1.3_7

47

Peirson-SmithA.Peirson-SmithB. (2020). Fashion archive fervour: the critical role of fashion archives in preserving, curating, and narrating fashion. Archives Rec.41 (3), 274–298. 10.1080/23257962.2020.1813556

48

PietiläT. (2020). Basotho blankets: ownership and appropriation. J. R. Anthropol. Inst.29 (1), 124–144. 10.1111/1467-9655.13823

49

RowleyJ. (2002). Using case studies in research. Manag. Res. News25 (1), 16–27. 10.1108/01409170210782990

50

RauserA. (2020). Madras and muslin meet Europe: on neoclassical cultural appropriation. Lapham's Q. Available online at: https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/madras-and-muslin-meet-europe (Accessed January 26, 2025).

51

RizziG.BertolaP. (2025). Exploring the generative AI potential in the fashion design process: an experimental experience on the collaboration between fashion design practitioners and generative AI tools. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy15 (May), 13875. 10.3389/ejcmp.2025.13875

52

RizziG.CascianiD. (2024). A.I. into fashion processes: laying the groundwork. Fash. Highlight (2 (February), 12–20. 10.36253/fh-2490

53

RosenbergerR.VerbeekP.-P. (2015). Postphenomenological investigations: essays on human–technology relations (Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books).

54

SaldañaJ. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

55

SärmäkariN. (2023). Digital 3D fashion designers: cases of atacac and the fabricant. Fash. Theory27 (1), 85–114. 10.1080/1362704x.2021.1981657

56

SayemA. S. M. (2022). Digital fashion innovations for the real world and metaverse. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ.15 (2), 139–141. 10.1080/17543266.2022.2071139

57

SchnappJ. (2016). “Buried (and) alive,” in Decolonising archives (L’Internationale Online), 17–22.

58

Slam Jam (2021). CIRCLE: march monthly highlights. Culture. Available online at: https://it.slamjam.com/blogs/editorial/circle-march-monthly-highlights-copy?shpxid=8f46e5c2-4da2-4b2e-ac2c-ce8a29cb1387 (Accessed January 26, 2025).

59

SnelgroveL. (2025). Making it work: Kim jenkins and the fashion and race database. Fash. Stud. J. Available online at: https://www.fashionstudiesjournal.org/profile/2020/10/29/making-it-work-kim-jenkins-and-the-fashion-and-race-database (Accessed January 26, 2025).

60

SpicherM. R.BernatS. E.Domozlai-LantnerD. (2024). Digital fashion: theory, practice, implications (London: Bloomsbury Publishing).

61

StolerA. L. (2002). Colonial archives and the arts of governance. Archival Sci.2 (1–2), 87–109. 10.1007/bf02435632

62

TaylorL. (1998). Doing the laundry? A reassessment of object-based dress history. Fash. Theory2 (4), 337–358. 10.2752/136270498779476118

63

Tepe (2024). “Designing expressions of body-fabric-space intra-actions,” in Doctoral dissertation, högskolan i borås.

64

TrontoJ. C. (1993). Moral boundaries: a political argument for an ethic of care. New York: Routledge.

65

VaccaF.VandiA. (2023). “Fashion archive as metamedium unfolding design knowledge through digital technologies,” in Connectivity and creativity in times of conflict. Cumulus Antwerp 2023. Ghent. Editors VaesK.VerlindenJ. C. (Antwerp, Belgium: Academia Press).

66

van ManenM. (1990). Researching lived experience: human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. London: Althouse Press.

67

VänskäA.GurovaO. (2022). The fashion scandal: social media, identity and the globalisation of fashion in the twenty-first century. Int. J. Fash. Stud.9, 5–27. 10.1386/infs_00045_1

68

YinR. K. (1993). Applications of case study research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

69

YinR. K. (1994). Case study research: design and methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Summary

Keywords

decolonisation, fashion archives, digital innovation, postphenomenology, case studies

Citation

Rodriguez Schon V and Valle-Noronha J (2025) Experiencing digital fashion archives through a decolonial lens. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 15:14563. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2025.14563

Received

28 February 2025

Accepted

31 July 2025

Published

18 August 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Rodriguez Schon and Valle-Noronha.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Victoria Rodriguez Schon, victoria.rodriguez@polimi.it; Julia Valle-Noronha, julia.valle@aalto.fi

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.