Introduction

The institutional landscape of Italian fashion and textile archives has undergone many changes over the past two decades, especially in response to the increasing need for accessibility and new value-enhancing strategies supported by private and public funding. Within this landscape, the Fondazione Antonio Ratti (FAR) in Como, Italy, is situated as one of Italy’s most prominent textile institutions and this paper’s case study. In 1998, FAR introduced an innovative multimedia catalogue to organise records and photographic reproductions of the textiles, which was later linked to the website launched in 2011, making a portion of the collection accessible online. In the late 2010s, the database underwent a complex renovation project, which resulted in the development of a new tool, called Digital Caveau, launched in 2023. This paper aims to review the evolution of the FAR textile collection and its digital catalogue and is written as a conversation between a fashion historian (first section) and the keeper of the collection (second section).

From corporate collection to structured catalogue

There exists a long-established tradition of textile collections in Europe, derived from the collections of textile entrepreneurs, who were not only interested in historical artefacts as tools for inspiration but also invested in their preservation and research. The FAR collection sits within this tradition, as it originated from the private collection of Antonio Ratti, who established a silk manufacture in Como in 1945. The former curator of the FAR, Francina Chiara, reconstructed the history of the collection, dating it back to the mid-1960s, at a time when the company was adopting a new strategy to diversify the production and position it at the high end of the market (Chiara, 2013).

The collecting strategy of Antonio Ratti might have been initially spontaneous and led by the purpose of inspiration, but it soon became strategic, especially regarding the acquisition of the archives of the textile companies he took over. Ratti purchased the first corporate archive in 1969, an unusual practice at the time. It was the archive of the company created by Guido Ravasi (1877–1946), an important artist-entrepreneur of the Como silk manufacturing district (Rosina and Chiara, 2008). The collection consistently grew over the next two decades: according to Chiara Buss, keeper of the FAR textile collections from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s, Ratti aimed at supporting scholarship, preserving heritage, and building a comprehensive collection (Buss, 2024). This approach was in line with the broader corporate policy that Ratti employed for cultural promotion in his company (Benedetti, 2017).

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, strategies were put in place to study the collection, assess its historical and cultural relevance, and organise it into a structured archive. This signals a shift from a private corporate collection to an institutional collection (Belk, 1995). Ratti recognised the importance of enhancing the value of his collection and displayed it through exhibitions and publications; he sought the support of scholars to achieve this.

In 1985, Ratti established the Fondazione Antonio Ratti with the aim to foster research and cultural programming dedicated to art and textiles (Augello, 2022). In the 1990s, he appointed experts to undertake research on different sections of the collection and to edit themed catalogues: Silk, Gold and Silver (Buss, 1992), Qibti (Donadoni Roveri, 1993, Cravates: Women’s Acessories in the 19th Century (Peter-Muller, 1994), Cachemire (Lévi-Strauss, 1995), Velvets (Buss, 1996), and Silk and Colour (Buss, 1997).

The institutional, collective perspective is best epitomised by the exhibition Silk. The 1900s in Como, organised by FAR in 2001. It was curated by Chiara Buss, keeper of the FAR textile collection, in collaboration with textile and fashion scholars. The display offered an unprecedented insight into the Como silk industry as manufacturers opened their archives for the first time (Buss, 2001).

Another pivotal change in the shift towards an institutional collection was the increased accessibility in the 1990s. The collection had been available to scholars upon request (Buss, 2017) but, in 1993, the textile collection was formally donated to the FAR. Ratti commissioned architect Luigi Caccia Dominioni to design a tessilteca [textile library] that would address the conservation needs of the textiles (Chiara, 2013) and facilitate its fruition.

The exchanges with the company’s employees and clients—who could access the collection for inspiration—and with scholars who researched it, alongside the growth of the collection and the establishment of the textile library, led to the recognition that a structured cataloguing system was needed to optimise organisations and search operations (Buss, 2024). In 1998 Ratti appointed textile historian Chiara Buss to undertake this task. Buss worked on the first digital catalogue of textile collections in Italy for the Poldi Pezzoli Museum in Milan: it launched in 1995 and received Italy’s highest design recognition in 1998—the Compasso d’Oro Award by the Associazione per il Disegno Industriale [Association for Industrial Design]—for the following reason:

An excellent example of the application of new technologies for communication, realised without resorting to technical exaggerations of the possibilities of hypertext and multimedia. It combines relevant information content with a healthy sobriety of tools that makes navigation particularly effective.

(Fondazione ADI, 1998: 4)

The Poldi Pezzoli textile collection was limited and, as Buss reported to the authors (Buss, 2024), the complexity of developing a database for FAR was due to the size of its collection, counting many thousands of artefacts. As there existed no models that suited the needs of FAR, the search criteria and structure of the multimedia catalogue, which had to allow the inclusion of photographic reproductions of all entries, were developed directly in response to the contents of the FAR collection.

The clusters of the collection became the main categories: individual ancient textiles (referred to as antichi singoli), mainly modern Western European, then coptic textiles, cravates, cashmere shawls, sample books, and garments (vesti). Each of these were then divided into sub-groups,- such as weave, provenance, and decorative pattern, and the options for each sub-group were determined by what was in the collection rather than adding a standard, broad range of options. Buss recounted that this was a trial and review process, an exchange between the software engineers and herself (a textile historian), finding better solutions that would capture the extensive textile variety of the collection (Buss, 2024). The backend was finalised in 1998 but the frontend continued to evolve until its final form in 2001.

The launch of the multimedia catalogue in 1998 was celebrated with the exhibition Navigando tra le sete. At that time, the catalogue included 800 entries (Colombo, 1998). Curators continued to contribute to the catalogue, updating entries and inserting new images when digitisation campaigns were undertaken. The biggest limitation to these campaigns were the funds required at the time for digitisation, for which the appointment of external service providers was required. The sample books constituted the biggest part of the collection and, since a complete digitisation was not possible, it was decided that only 10% of each book would be reproduced. The selection of which samples in the books to reproduce was made jointly by the textile curator and a representative from the Ratti manufacture, thus the choice did not only take into consideration curatorial aspects but also appeal to clients (Rosina, 2025).

The catalogue could only be accessed onsite until 2011, when the FAR commissioned a new website that incorporated the catalogue: by using the same criteria, users could search the collections and view low-resolution images of the artefacts. This proved difficult as the database was showing signs of ageing and the translation of its system into a website with the then-available technologies was a slow and complex process (Rosina, 2025).

The strategy to increase accessibility took place alongside the growing, nation-wide recognition of the importance of fashion heritage. In 2010 the SAN, Sistema Archivi Nazionale (National Archival System), launched the digital portal Archivi della Moda del Novecento (Archives of Twentieth-Century Fashion), which gathered data from more than two hundred public and private institutions. The aim was to ‘to discover, enhance, and make available a wide range of sources, so far unexplored, of the archival, bibliographical, iconographic, [and] audiovisual heritage related to Italian fashion’ (SAN, 2010).

Similar projects at an international level soon followed. Europeana Fashion, a best-practice network of 22 institutions from 12 European countries, ran from 2012 to 2015. The purpose was to aggregate and harmonise existing digital content from these institutions and integrate it on the Europeana platform (Europeana Pro, 2015). Another platform with broader scope, We Wear Culture, was launched by the Google Cultural Institute in 2017 (Melchior, 2019).

Despite the boost of digital archival technologies in the late 2000s and early 2010s and the development of integrative platforms (Calanca, 2020), the accessibility of corporate archives was still questioned due to the importance of heritage as a crucial element of differentiation for companies (Augello, 2022). Many corporate archives are still not accessible to the public or, as in the case of Armani, it is only accessible onsite at the Armani/Silos in Milan (Franceschini, 2019).

The collection of FAR is accessible to the Ratti manufacture but the foundation is legally and financially independent from the company, thus relieving it from ties that corporate archives have. On the other hand, not being linked to a functioning company with an active communication strategy reduces resources and chances for communication, which impacts public awareness of the collection. As recounted by Margherita Rosina, keeper of the FAR textile collection from 2007 to 2016, the collection was made more accessible with the integration of the database to the website, but it was not combined with a promotional strategy beyond the existing network of the collection, eventually counteracting the accessibility strategy (Rosina, 2025). Given the extensive investments required by the development of digital archival tools and digitisation campaigns, it is fundamental to allocate sufficient resources to promote the use of these tools in order to ensure a return that justifies those investments.

From structured catalogue to digital caveau

The working definition of archived employed thus far aligns to that of Italy’s foremost encyclopaedia, Enciclopedia Treccani:

1. a. Collection of private or public records relating to a person, family, municipality, state, etc.: b. Location where the collection is permanently located, and the offices that are part of it. 2. […] b. In information technology, an organized set of homogeneous reference data, constantly or periodically updated, from which an automatic processing or documentation system can obtain indexes, tables, etc. An archive that is large and accessible to a larger or smaller audience is called a database.

It is worth highlighting the difference between the corporate archive of the Ratti company and the FAR archive, not only from an organizational point of view but mainly because the two institutions have different purposes.

The mission of the Foundation is, by statute, to allow the archives to be open to the public; Antonio Ratti decided to establish the Foundation in order to open his private collection and library to the public.

The archive of the Ratti company, to protect the privacy of their customers, is accessible only to those who are part of the company itself and often with great limitations. Access to the archive is not allowed to all employees, only those in the production and sales department are authorised with personal passwords to access the digital archive; the physical archive is accessible on request to the office in charge.

The archive consists of all the fabrics produced and commercialized by the company itself. It is divided into two macro categories and it is stored within two spaces close to each other. In the first one there are documents such as drawings, sketches, or sample books kept in numerical order; in the second one, all the historical sample of fabrics produced since the origins of the company are stored. The criterion of division by decorative motif, such as floral, geometric, cashmere, and animal, was applied here. One section is dedicated to the productions of acquired collections—for example Rainbow and Carnet—and another to the collections of some of the most important clients, such as Versace (Ratti, 2025).

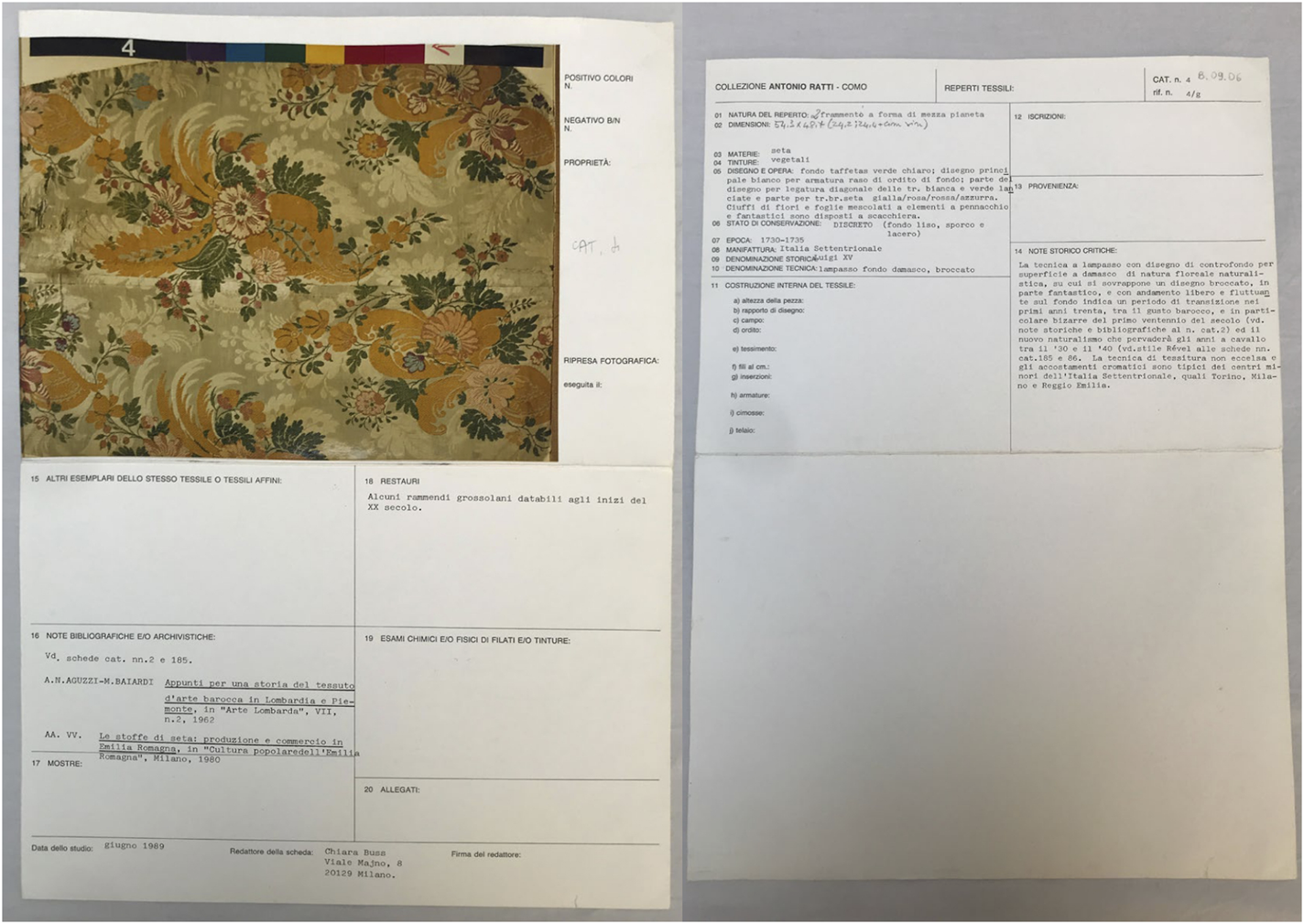

The two archives split in 1985 when Antonio Ratti decided to open his private collection to the public, as described in the previous section. In 1995, Antonio Ratti, after years of cataloguing the collection in paper form (Figure 1), proposed to the Foundation’s director, Chiara Buss, to study the possibility of digitizing the FAR collection. It was a forward-looking project with no reference model. The director worked with a computer science engineer to study the feasibility together.

FIGURE 1

Paper sheet, front and back, FAR digital catalogue, 1995.

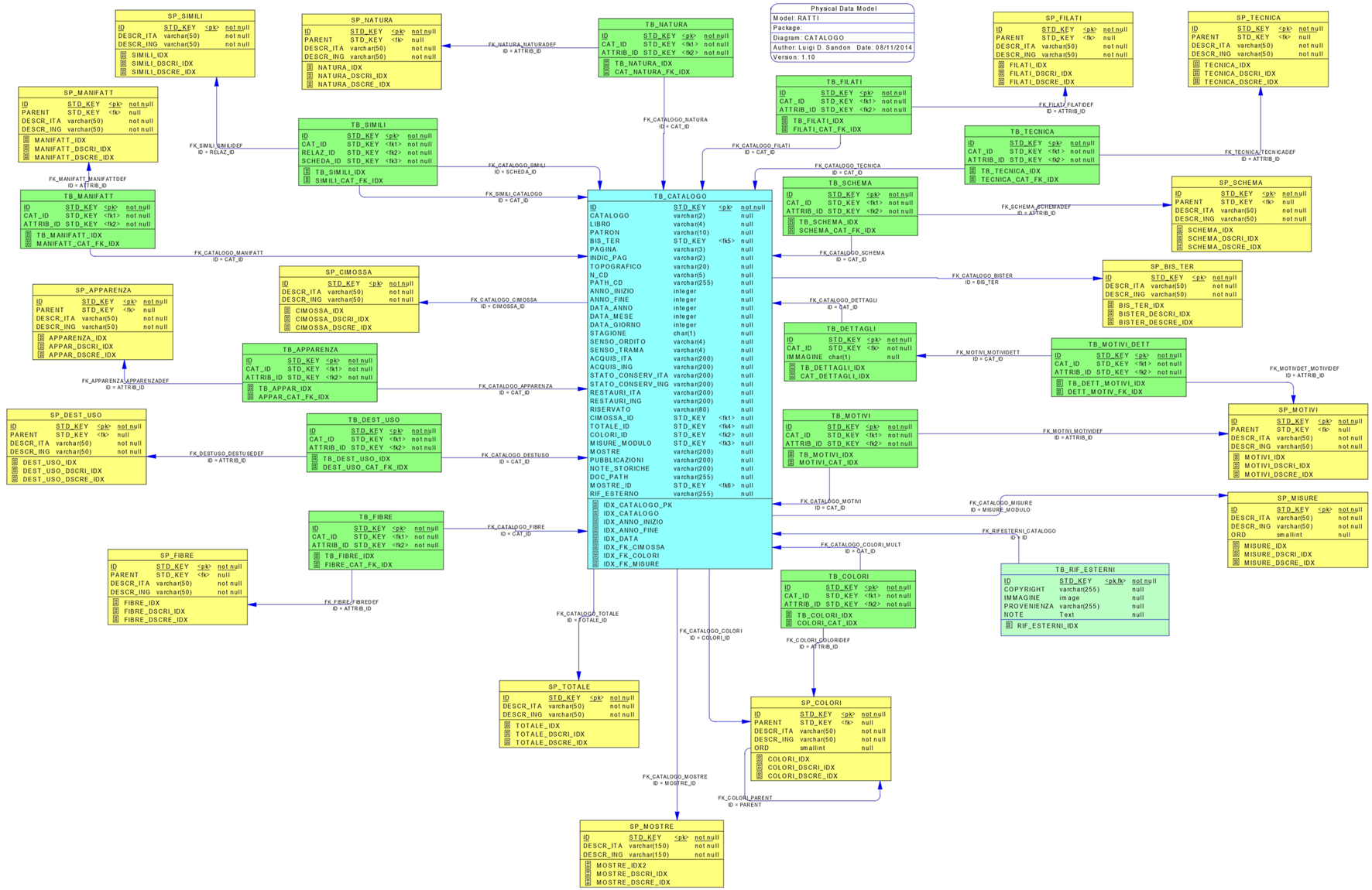

The first step was learning each other’s technical language to prepare the backend architecture (

Figure 2). The development of the tool involved:

1. Creating lists with all the subdata for each lemma to be poured into the system

2. Developing a record sheet that could contain all the useful data for describing the different types of objects contained in the collection, such as garments, accessories, fabric fragments, and headdresses

3. Undertaking the photo campaign for each individual object to complete the sheet

4. Choosing which and how many items to include in the catalogue.

FIGURE 2

Hierarchical relationship diagram, FAR catalogue, 1998.

Also included in the catalogue were management data not visible in the frontend, topographical, critical historical notes, and preservation sheets.

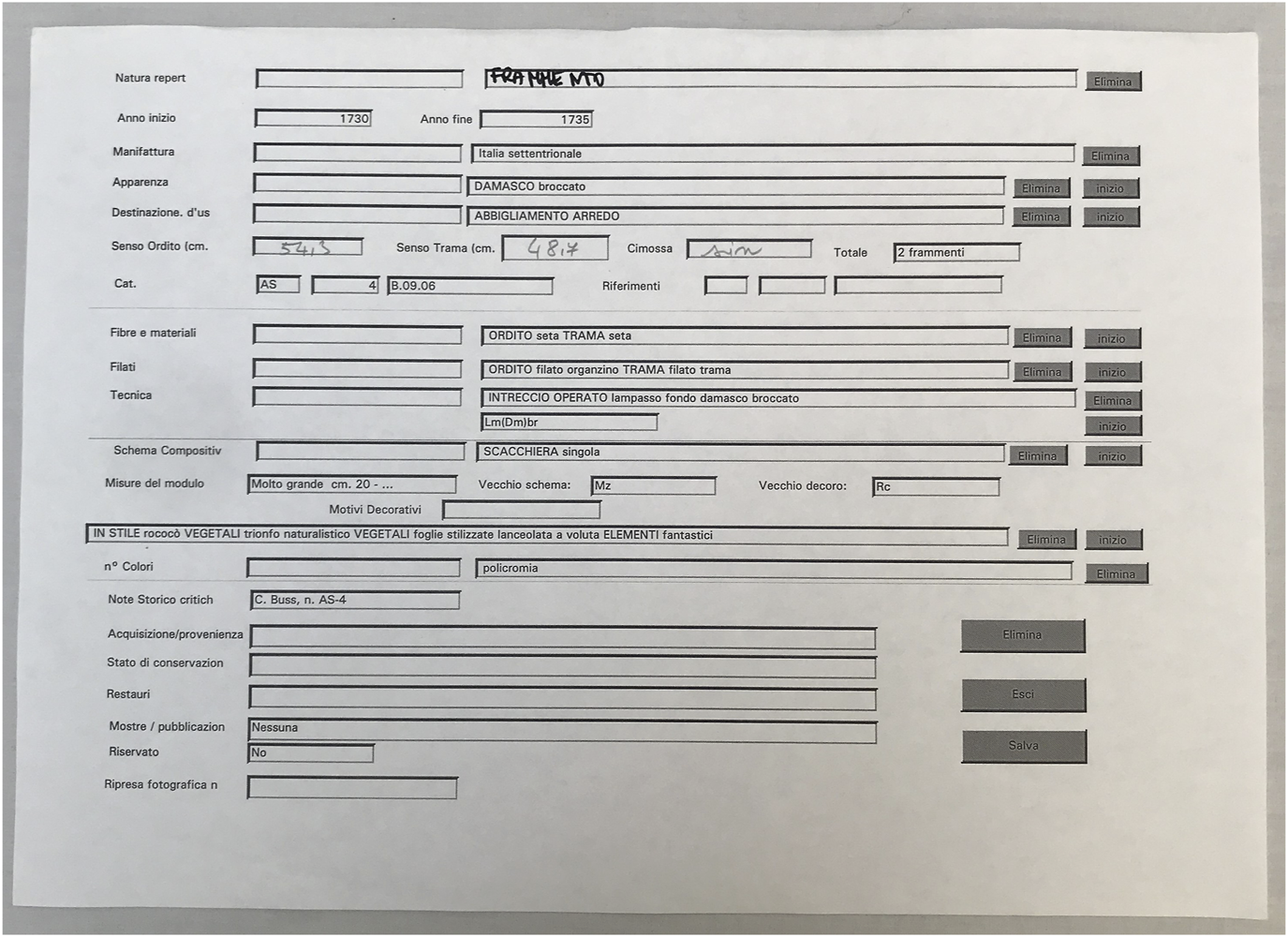

This new tool facilitated searches by the foundation staff and was accessible to the public in computers installed in the FAR library. Thus, staff members had the ability to select items in their customized search. Figure 3 reproduces an image of the first digital archive.

FIGURE 3

Backend, FAR catalogue, 1998.

In 2018, the operating system was obsolete and the metadata storage server was collapsing. Actions were needed to preserve the heritage, therefore updating the catalogue became a practical and urgent need.

The search for the new platform began in 2015, but only in 2018 was the most optimal solution from both management and economic points of view found. After 4 years of work, the digital tool, which consists of a data entry part and an exploration interface, was developed.

The storage facility at FAR is called caveau, a French term that describes a vault where money or valuable objects are kept, so the name Digital Caveau was chosen for the new database to reference the FAR history. Free access is provided to anyone who requests it, and there is a diverse audience from students to artists, scholars, and industry professionals. FAR has established solid relationships by networking with Italian universities such as La Sapienza in Rome, La Venaria Reale in Turin, and Naba and Marangoni in Milan and with foreign institutions and universities, such as FIT in New York and the Uzbekistan Government. Unfortunately, the database is only in Italian as the translation of technical terms requires extensive research, and this is one of the challenges FAR hopes to resolve in the near future.

The creation of this tool raised some technical and content difficulties:

1. The entire system had to be revised to be able to import existing data into the new database, which is not an ad-hoc system like the previous one but is instead based on a standard model. This standard model relies on a digital platform that traces Italian ministerial records for the description of objects of historical and artistic interest (ICCD, n.d.). The difficulty of this migration lies in analysing the structure of a system that is restricted and technologically dated to a system that is standardized with a technology that leans on 20 years of technical developments. Therefore, the system had to take into consideration two different systems and find an effective solution to preserve the data

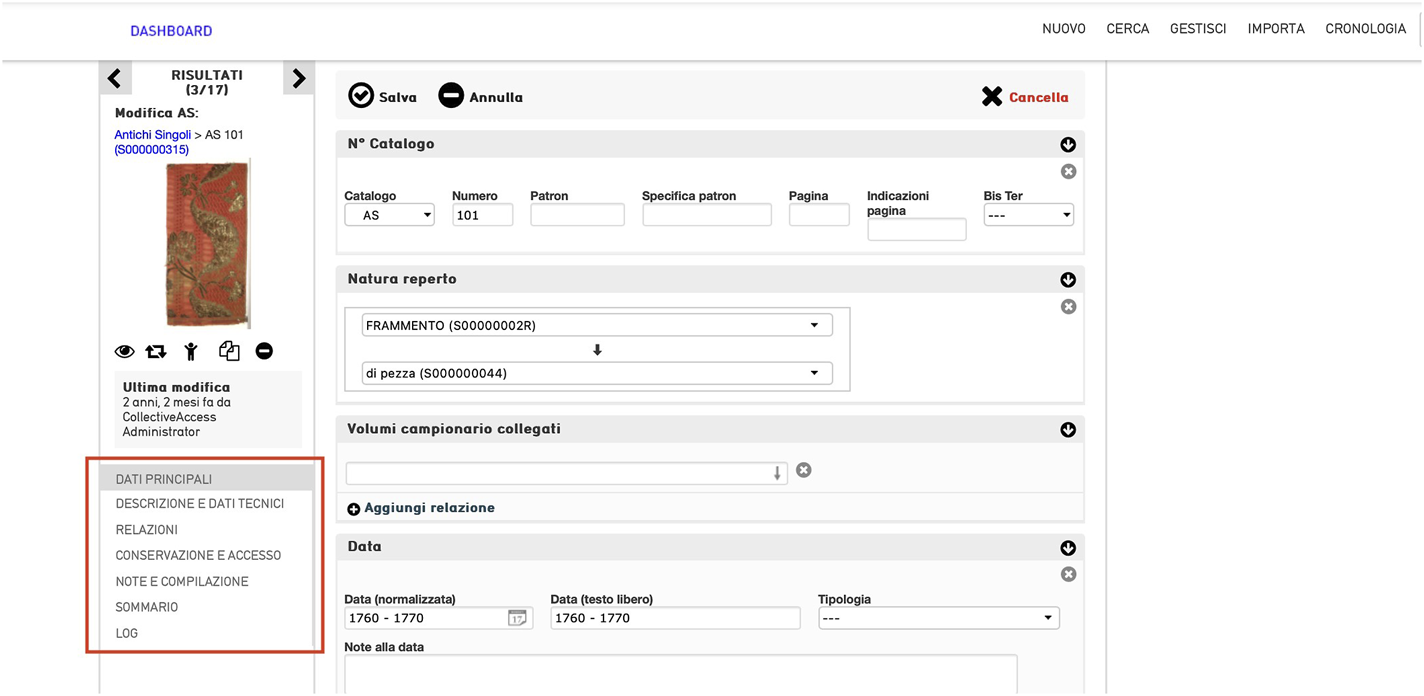

2. Entry forms were modelled for each type in the collection (Figure 4).

3. One of the main challenges addressed with the new database was developing a system that would provide accurate descriptions of the heterogenous artefacts in our collection. This point required modifying the existing structure to differentiate cataloguing sheets and increase data entry fields. Specific sheets were created for drawings and sample books, whereas before there were only sheets for single samples in the books. There were also sheets for garments that could be integrated with sub-sheets relating to the materials in which they are made. In addition, a hierarchical-relational structure with layered connections was employed, while the previous structure was horizontal. Dedicated sheets on exhibitions, publications, donors, and companies were added, which resulted in a much broader network of data where one could not only search for artefacts but also for the events, people, and activities related to them.

4. Each record sheet contained four sections: Main data, technical data, reports, conservation and summary (Figure 5). The first two sections, related to existing data in the catalogue, were migrated as a whole to the new database, while Relazioni [relations] and Conservazione [conservation], as well as a section for notes in the backend, were added and filled in one by one.

5. The creation of management tools has meant massive migrations of images and data from matrices, processing of sets (data groups), the creation, editing, and addition of vocabulary lists, and relationships between database entities.

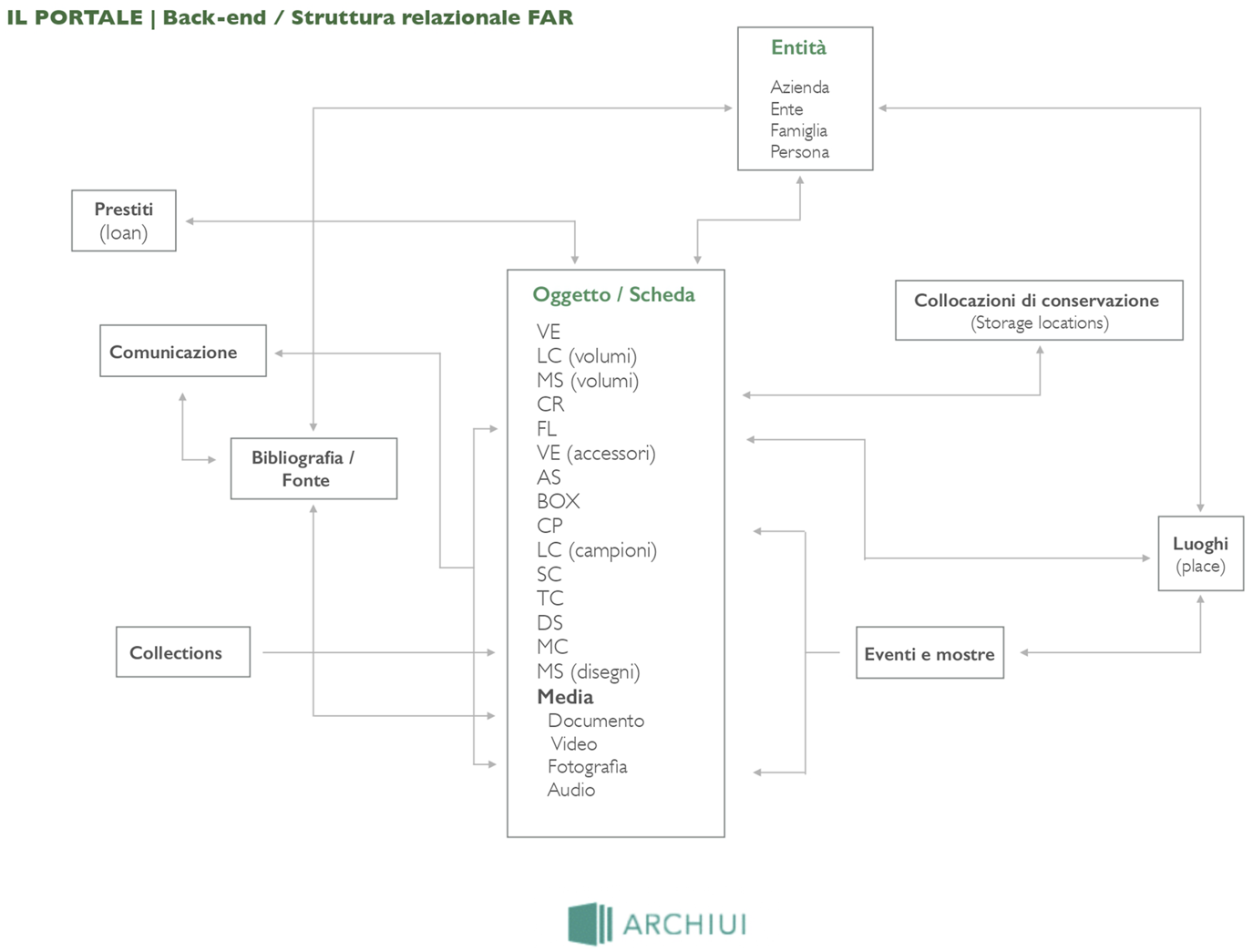

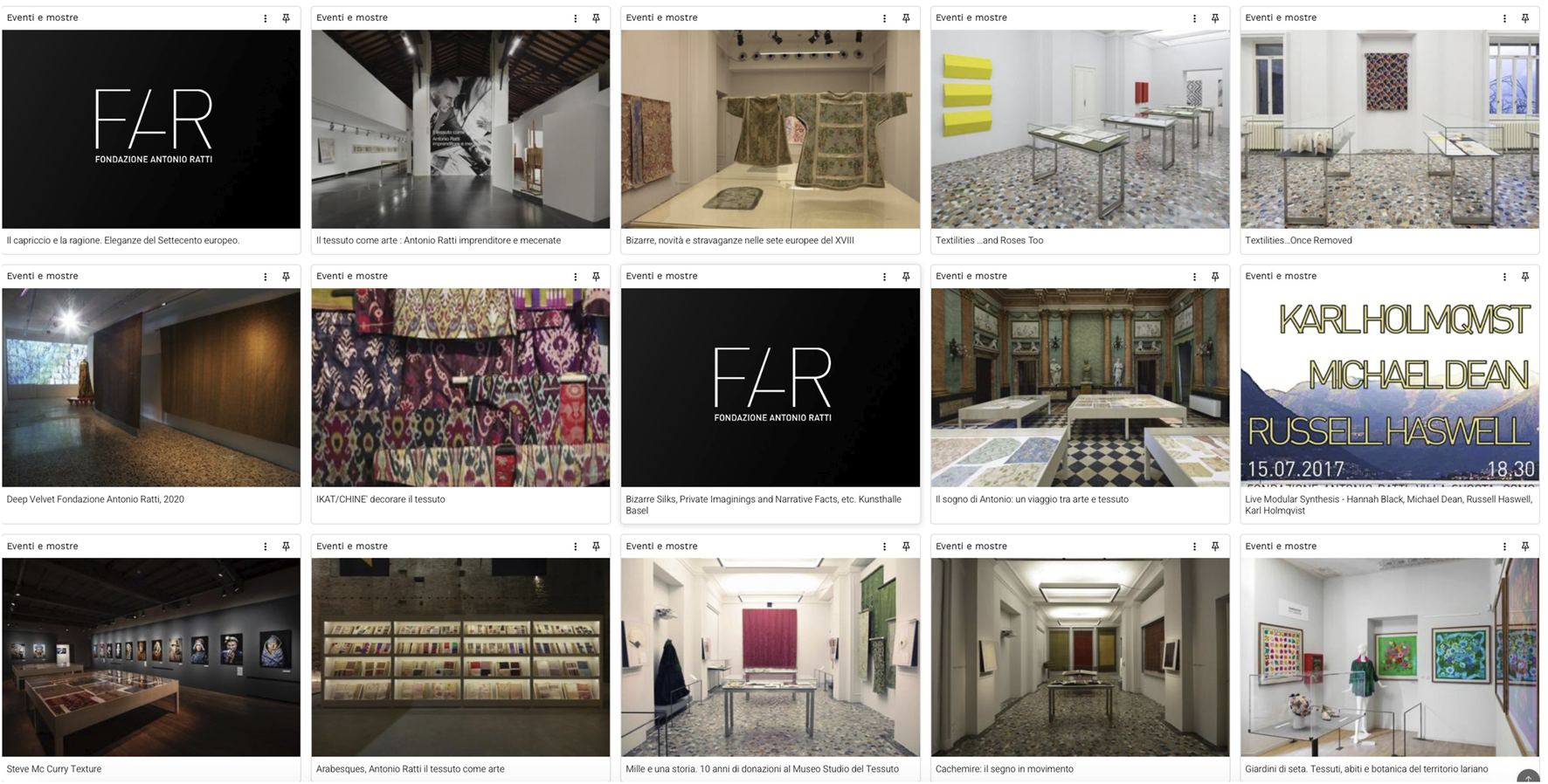

6. The creation of new descriptive sheets for entities that are not objects but are related to them, such as Donors, Funds, Bibliography, Exhibitions, People, Authors, Curators, and Entities (Figure 6).

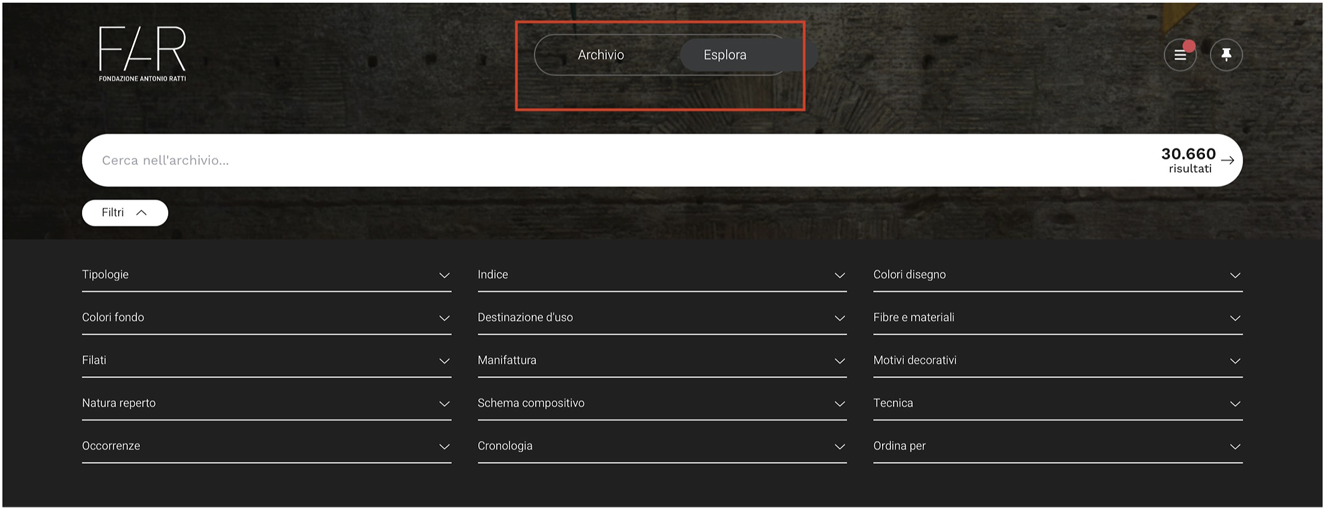

Four years later, the frontend was created with the same IT support. The frontend has two sections. Archive aims to support users in their navigation: it features a timeline and themes through which general searches can be started. Explore allows for advanced searches with filters such as provenance, date, material, technique, colour, and decorative pattern (Figure 7).

FIGURE 4

Hierarchical relationship diagram, FAR catalogue, 2018.

FIGURE 5

The sections of the current record sheet, Caveau Digitale, 2025.

FIGURE 6

Overview page of the descriptive sheets dedicated to exhibitions, Caveau Digitale, 2025.

FIGURE 7

Frontend, Caveau Digitale, 2025.

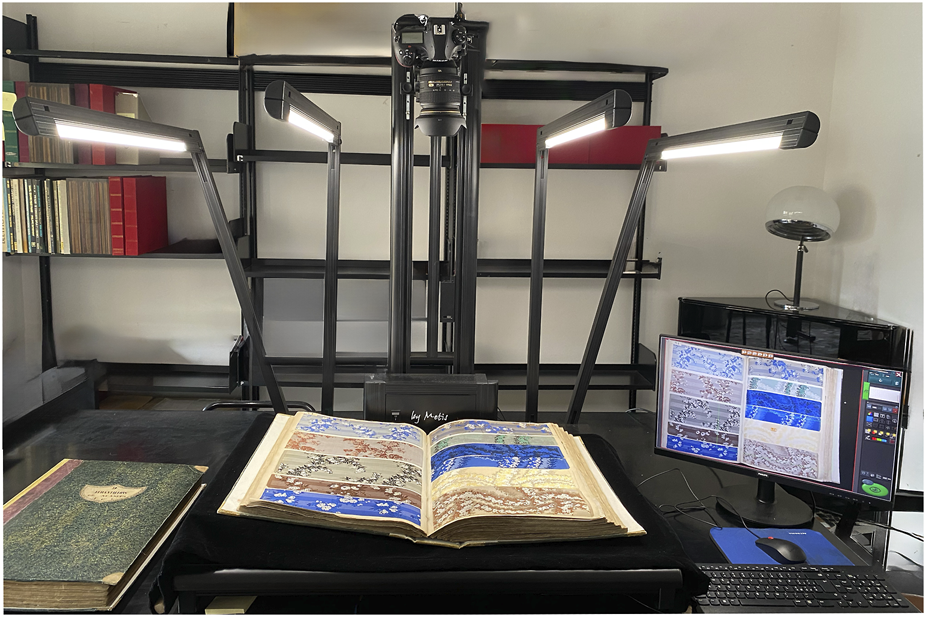

The Caveau Digitale provided the opportunity to devise wide-ranging projects such as massive acquisition campaigns that gave the possibility to draw on funding and apply for grants. Work streams were developed to provide access to financial resources in order to purchase hardware such as digital scanners that further facilitated cataloguing work (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8

Digital scanner installed at FAR, 2025. Images courtesy of Fondazione Antonio Ratti, Como, Italy.

A grant was awarded by Fondazione Alcea. The funding covered the salaries of a specialist conservator and an assistant, the restoration of 70 sample books and 2000 printing proofs, and the purchase of a scanner which allowed the digitisation of the artefacts. Before purchasing this equipment, FAR had to rely on external photographers for digitisation. Being able to carry out these operations independently allows for greater precision in the acquisition of data and has significantly sped up the process, drastically reducing the resources required.

In addition, the new platform, because of the way it is structured, offers great versatility of action. This feature makes it possible to create functional boards and systems for describing specific assets by differentiating information according to category. For example, a new sheet was created for the category “Nuances”, following the digitisation campaign of the archive of the company Chavent Père et Fils, thanks to the grant awarded by the Fondazione Alcea. Over the last 2 years, it has been possible to digitise more than 15,000 images, making a massive contribution towards fully remote accessibility to the collection.

The Digital Caveau now allows users to consult sample books in their entirety: they can view spreads with pieces side by side, as they were originally glued together when the books were made, and can flick through the pages. This fruition mimics the physical experience of visiting the archive and provides valuable information that had been unavailable to remote users until now.

Since the death of Antonio Ratti in 2002, the collection has continued to grow thanks to targeted purchases by the FAR, often with the support of sponsors (Epson) and to donations such as those by textile manufacturer Alberto Tagliabue (2010), at the bequest of the family of fashion historian Grazietta Butazzi (2015) and curator and collector Seth Siegelaub (2022). It also hosts a library with more than 16,000 volumes specialized in textiles, fashion, and visual arts and crafts, which is part of the local public library system. The catalogue now counts more than 30,558 sheets and 73,773 pieces of data.

Conclusion

The Digital Caveau goes beyond the format of structured archive with rigorous cataloguing and is designed as a multi-faceted and user-friendly tool with the aim to enhance the value and fruition of the FAR textile collection. While a portion of the archive was already accessible remotely from 2011, the new platform allows full remote access.

The added value of the Digital Caveau is to have a large relationship archive where objects are not taken out of context but considered in their broader value system, allowing consideration of the relationships between other objects, entities, people, exhibitions, and activities, thus developing a grand narrative.

This new configuration aligns with contemporary digital archives, described by Martin and Vacca (2018) as “dynamic, open, multidirectional, and polysemous” (2018: 337).

Future plans include the study and digitisation of unexplored clusters of the FAR collection, such as the archive of the Lyonnaise textile manufacturer Brochier and the ethnological artefacts collected by Seth Siegelaub. The other key process in the integration of all FAR holdings will be the migration of the entire library records to the Digital Caveau.

In addition to the employment of digital technologies to enhance remote accessibility, the FAR is also broadening its programming for physical accessibility to its collection. Themed courses on the history of textiles are led by specialists and aimed at creatives working in the silk manufacturing district of Como, alongside visits organised for fashion and textile students in secondary and higher education. In 2024, the institution launched the project Open Archive, which entails a series of study days for small cohorts of participants to explore different sections of the collection, with talks and handling sessions led by specialists.

This case study has shown how technologies can be employed effectively to address multiple users and needs and that their updating is fundamental to enhance the value of a collection and ensure its accessibility to all stakeholders, from industry creatives to scholars and the local community. We invite readers to get in touch and explore FAR’s Digital Caveau.

We would like to thank the editors of this special issue, Federica Vacca and Paola Bertola, for inviting us to share our thoughts on this valuable experience and providing a chance to reflect on the recent changes implemented at the Fondazione Antonio Ratti and their results. We would also like to thank the FAR president Annie Ratti for her support and Chiara Buss, creator of the first FAR database, whose testimony was crucial for writing this paper.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The manuscript was conceived and reviewed jointly by the authors. It comprises two main sections, the first written by MA and the second written by MT. Introduction and conclusions were written together.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

References

1

AugelloM. (2022). Curating Italian fashion: heritage, industry, institutions. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

2

BelkR. W. (1995). Collecting in a consumer society. London: Routledge.

3

BenedettiL. (2017). Textile as art: Antonio Ratti entrepreneur and patron. Ghent: MER Paperkunsthalle.

4

BracunE.Hagedorn-SaupeM. (2015). Europeana fashion. Handb. Kult., 268–276. 10.1515/9783110405774-025

5

BussC. (1992). Silk, Gold and silver. Milan: Fabbri Editore.

6

BussC. (1996). Velvets. Como: Ratti.

7

BussC. (1997). Silk and colour. Como: Ratti.

8

BussC. (2001). Silk: the 1900’s in Como. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale.

9

BussC. (2017). “Collezione Antonio Ratti,” in Il tessuto come arte: Antonio Ratti impreditore e mecenate. Editor BenedettiL.Ghent: MER Paper Kunsthalle, 159–160.

10

BussC. (2024). Conversation with authors.

11

CalancaD. (2020). Archivi digitali della moda e patrimonio culturale tra descrizione e integrazione. ZoneModa J.10 (2), 11–25.

12

ChiaraF. (2013). “Antonio Ratti and his textile collection,” in Collecting textiles. Patrons collections museums. Turin. Editor RosinaM.Como: Allemandi and Co., 11–32.

13

ColomboM. (1998). Il catalogo multimediale dei tessuti antichi. Not. Tec. tessile48 (4), 14.

14

Donadoni RoveriA. M. (1993). Qibti. Como: Ratti.

15

Fondazione ADI (1998). “Premio Compasso d’Oro 1998,” in Motivazioni per la giuria. Available online at: https://www.adi-design.org/upl/CdO_STORICO/CdO%20storico%20MOTIVAZIONI/Motivazioni_1998.pdf (Accessed October 11, 2024).

16

Fondazione Antonio Ratti (2024). About. Available online at: https://fondazioneratti.org/about (Accessed October 11, 2024).

17

FranceschiniM. (2019). Navigating fashion: on the role of digital fashion archives in the preservation, classification and dissemination of fashion heritage. Crit. Stud. Fash. and Beauty10 (1), 69–90. 10.1386/csfb.10.1.69_1

18

ICCD (nd) Catalogazione. Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione. Dipartimento del Ministero della Cultura, Rome, Italy. Available online at: https://www.iccd.beniculturali.it/it/Catalogazione (Accessed 13 May 2025).

19

Lévi-StraussM. (1995). Cachemire. Ratti: Como.

20

MartinM.VaccaF. (2018). Heritage narratives in the digital era: how digital technologies have improved approaches and tools for fashion know-how, traditions, and memories. Res. J. Text. Appar.22 (4), 335–351. 10.1108/rjta-02-2018-0015

21

MelchiorM. R. (2019). Digital fashion heritage: understanding europeanafashion.eu and the Google cultural institute’s we wear culture. Crit. Stud. Fash. and Beauty10 (1), 49–68. 10.1386/csfb.10.1.49_1

22

Peter-MullerI. (1994). Cravates: Women’s accessories in the 19th Century. Como: Ratti.

23

Ratti (2025). azienda. Available online at: https://ratti.it/azienda/archivio/.

24

RosinaM. (2025). Conversation with authors.

25

RosinaM.ChiaraF. (2008). Guido Ravasi. Il signore della Seta (Como: Nodo Editore).

26

SAN (2010). Pitti, non solo immagine. Available online at: http://www.moda.san.beniculturali.it/wordpress/?percorsi=1988-nasce-pitti-immagine (Accessed October 11, 2024).

27

Treccani.it (2025). Archivio. Encicl. Treccani. Available online at: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/ricerca/archivio/?search=archivio (Accessed April 29, 2025).

Summary

Keywords

textile collection, digital archive, corporate institution, accessibility, silk industry

Citation

Augello M and Terragni M (2025) From corporate collection to Digital Caveau: enhancing the value and accessibility of the textile collection at the Fondazione Antonio Ratti. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 15:14430. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2025.14430

Received

31 January 2025

Accepted

21 May 2025

Published

11 June 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Augello and Terragni.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maddalena Terragni, maddalenaterragni@fondazioneratti.org

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.