Abstract

In this study, I attempt to “map” the cultural policy pursued ideologically and give it a sociological interpretation of values. My hypothesis is that cultural policy is driven by values and interests. After all, those who implement cultural policy face numerous choice dilemmas. This research on potential characteristics of cultural policy, draws on a range of sources: on scholarly literature that links ideology and cultural policy and addresses values and justifications. Of course, cultural policy is also analysed on the basis of publications, policy texts, real policies, and qualitative interviews with key figures. This is how I arrived at a diagram of political-ideological characteristics of cultural policy. I group these into two overarching categories, progressive/conservative and left/right cultural policy. I arrange the characteristics as choice variables, each placed on a continuum. I develop a visual model with an x-axis containing the left and right characteristics and a y-axis containing the conservative and progressive characteristics. Plotting both categories on an x- and y-axis also clearly shows the relationship between them. The two categories of characteristics act as a tool to ideologically define each type of cultural policy.

Introduction

In what ways can one analyse the bureaucratic and instrumental functioning of national cultural policy systems? Is the study of cultural policy archetypes appropriate for comparative cultural policy research? American anthropologist Rosenstein (2018) notes a methodological poverty of the widely used cultural policy archetypes, though they do tell us something about cultural ideologies in simple and powerful ways. Other authors believe that existing typologies contain several inconsistencies. The creation of a typology has limitations. It narrows categories, simplifies assumptions, truncates standards and consequences. In practice, certainly in Europe, policy practice is diverse and nuanced. French sociologist Dubois (2013) argues that reality is not so unambiguous. Moreover, in Western Europe, cultural policy is divided between supra-national, national and infra-national policy levels, such as Flanders (Belgium). Each typology hides quite a lot of overlap and ambiguity. More than that, a matrix is static and in no way reflects changes over time (Bell and Oakley, 2015). Any form of ideal typology tends to exaggerate the differences between policy models and underestimate the differences within each model.

About the research approach. My research combines different disciplines. In addition to sociology, I borrow insights from political science and public administration, and to a lesser extent from history. Analysing cultural policy benefits from a multidisciplinary approach.

I work in the field of interpretive policy studies (Yanow, 2000). Such research is based on a social world that can be interpreted in multiple ways. In this world, there is no “raw data” whose meaning is beyond dispute. Policy analysis involves interpretation. As a researcher, I interpret the social world, in this case everything that moves in and around cultural policy. All actors also interpret as they try to understand policy. Policy documents, legislation and implementation are also expressions of meaning in this method. This is also the case for the interviews I conduct. In such a framework, we speak of “double hermeneutics”: as a researcher, I interpret how the respondents or analysed texts interpret reality.

With the caveats and limitations, I set out to find an alternative model to characterise cultural policy. One potentially relevant basis for this is the ideological basis on which cultural policy is established. Can you characterise cultural policy ideologically? And if so, how? That is what I attempt to do: to map cultural policy ideologically and give it a sociological interpretation of values.

Materials and methods

From dilemmas to ideology

Cultural policy cannot be neutral. Those who pursue cultural policy “have” to make choices, choices for specific objectives and against others, and in doing so will want to set themselves against some previously adopted policies, or will want to differentiate themselves from previous policies. Cultural policy is constantly faced with choice dilemmas such as: is high culture the exclusive object of policy, or are other (forms of) culture also chosen? Or how broadly are arts and culture defined? Will traditional or innovative cultural expressions be selected? Does passing on and maintaining the canon prevail, or rather innovative artistic and cultural expressions? Does a cultural policy pay attention to audience participation? How does a cultural policy deal with the balance between nonprofit operations and the cultural industries? Does a cultural policy prioritize affirming or challenging cultural expressions? How important is the cultural/artistic autonomy of artists and cultural workers, both in relation to government and politics?

The list is far from exhaustive. There are numerous crucial dilemmas that present major challenges to any policy. The way of dealing with the dilemmas is usually ideologically inspired. This also creates tensions. For example, this dilemma: a progressive cultural policy encourages innovation and therefore experimental art, but at the same time it wants the arts to be accessible to everyone and everyone can become creators (cultural democracy). In practice, however, we see that the avant-garde still focuses mainly on a small group of insiders. How do these two goals relate to each other?

An ideological schema

First, the concept of ideology deserves some clarification. For this paper, an ideology is a coherent set of views on the organisation of society. Ideologies often derive their coherence from an underlying view of human nature (Hooghe et al., 2022).

Ideologies can be approached in different ways. For the purposes of this analysis, I chose not to start from what the literature says about liberalism, social democracy, Christian democracy, ecology, etc. After all, there are major differences in the way political families in many countries “translate” these ideologies. I went back to the core of existing ideologies. However, the ideological operationalisation of the left/right concept pair is not easy from a methodological point of view, and may even be problematic. These concepts have acquired multiple meanings. They require at least clarification. The same confusion has arisen in the use of the other pair of concepts that I will discuss below: conservatism/progressivism.

Another and perhaps even greater problem is that there is a (strong) tendency today to praise consensus politics and therefore to argue that the so-called ‘old-fashioned’ politics of polarisation between left and right is outdated. Anthony Giddens, the founder of the Third Way, and Ulrich Beck, who founded the theory of the risk society, in particular believe that the left/right paradigm is outdated. In post-traditional societies, they argue, there are no longer any constructed entities of “us” and “them” due to the dynamics of individualisation, so that political boundaries have disappeared (Mouffe, 2005). I do not share this view. I agree with Chantal Mouffe’s analysis of the work of Giddens and Beck: “For a well-functioning democracy, a clash of opinions, a struggle between different legitimate political positions, is a prerequisite. That is precisely what the confrontation between left and right should be about” (Mouffe, 2005). There is a deep divide between these two approaches to “the political.” Giddens’ individualisation thesis is situated at the level of “factuality,” while Mouffe rejects it on the basis of a normative argument (the need for a clash of opinions), which is situated at the level of “desirability.” Fact and desirability belong to different ontological levels.

On this basis, I have attempted to clarify the concepts. I draw, among other things, on the work of Lukes, who believes that the concepts of left and right are not outdated. What is left? He proposes to define left by its commitment to the principle of rectification (Lukes, 1997). This is based on the assumption that there are unjustified inequalities which are considered by the right to be sacred, inviolable, natural or inevitable, but which must be eliminated (Lukes, 1997).

Norberto Bobbio, an Italian political philosopher, argues that the two terms, an antithetical distinction, support each other: if there were no right wing, there would be no left wing, and vice versa. In his work, he seeks criteria to define left and right. The most important criterion is the “ideal of equality”: “I believe that the criterion most frequently used to distinguish between the left and the right is the attitude of real people in society to the ideal of equality” (Bobbio, 1996).

Weyers (1997) adds the criterion of “extension of rights” to left-wing political action. This makes it possible to assess political positions over time. In the second half of the 20th century, new themes emerged from new social movements. They addressed issues such as feminism, interculturality, decolonisation, migration, ecology, democratisation of education and culture, etc. It is plausible to call political positions that seek to expand rights “left-wing” and political positions that oppose this expansion “right-wing” (Weyers, 1997). Nevertheless, we also see a defence or recuperation of rights such as freedom of expression, gender equality, etc. on the right.

Based on the work of the authors mentioned above, I can distil key concepts and conditions to distinguish between left and right. The first overarching category includes the concepts of left and right.

The Left stands for the pursuit of (more) equality and freedom (in a balance with equality), expansion of rights, countering and eliminating unjustified inequalities, allowing more people to acquire the same opportunities for self-actualization, placing limits on the economy and market forces, and opposing commodification and commercialisation. The Left advocates a horizontal political space and political democracy.

The Right stands for a society in which the individual must assume his or her own responsibility (for self-actualization), also pursues the ideal of freedom but then in an absolute sense and not related to equality, opposes the expansion of rights, finds inequalities normal (combats only excesses), is in favour of free-market operation, including commodification, commercialization and limited government influence. The right also desires horizontality of political space, but it is not a prerequisite. Meritocracy is a guiding principle. The left-right axis relates mainly to social and economic issues.

Defining the concepts of conservative and progressive is also somewhat problematic. Over time, these terms have acquired multiple meanings. Clarifying them is not easy, partly because the progressive/conservative divide seems to blur the distinction between left and right.

For the analysis of conservatism, I focus primarily on Koselleck in Brunner et al. (2004) and Mannheim (2018). Karl Mannheim outlines two types of conservatism. For the first type, he believes it is better to adopt Max Weber’s term “traditionalism,” so that “conservatism” always refers to “modern conservatism”: Traditionalism denotes the tendency to adhere to persistent patterns, to old ways of life that we can very well regard as more or less ubiquitous and universal. Conservatism arises as a conscious political statement by individuals and groups who see their acquired rights threatened by changes in economic, social and political conditions. They defend themselves against this danger by identifying with the preservation of historical continuity, the validity of the law and the advancement of culture. According to Mannheim, the conservative way of life and thinking clings to the immediate, the real, the “concrete.” Progressive activity, on the other hand, is based on “the awareness of the possible.” “Freedom” is another crucial concept for the analysis. However, human freedom comes up against limits when it infringes on the freedom of fellow citizens. The logical consequence of this type of freedom is equality, because without the assumption of political equality of all people, this freedom is meaningless.

Conservatives have also developed their own qualitative concept of freedom to distinguish it from the egalitarian concept. They focused on the underlying idea of equality. This stated that people are “unequal,” including in terms of their talents and abilities. It is striking that conservatism is often nationalistic and patriotic. Strong emphasis is placed on one’s own identity and culture. There is also an international/global dimension to conservatism, such as the legitimisation of colonialism, unequal relations between ethnic and racial groups, etc.

Progressivism is based on social progress and the idea that advances in science, technology, economic development, sustainable development and social organisation are essential for improving the human condition (universalis.fr, 2024). The meanings of progressivism have varied over time and from different perspectives. In modernity, it is about more than linearity; it is also about the “opening up” of the future, as Koselleck has described it: from a “space of experience” to a “horizon of expectation” (Koselleck in Assmann, 2020). In the 21st century, progressivism has taken on a broad meaning. Progressives are characterised by advocating policies that combat ethnic and cultural discrimination, environmentally conscious behaviour, greater citizen involvement in democracy, an open ethical attitude towards abortion, euthanasia, and so on.

In society, especially in the political context, both pairs of concepts are often used as (almost) synonyms. This is not correct. Sometimes parallels can be found, but there are many more contradictions. Look at political practice. In terms of socio-economic policy, liberal parties range from centre-right to outright right-wing, but in Western Europe they are progressive on the ethical/cultural dimension. Socialism is left-wing and usually progressive, but is often conservative in areas such as democracy, citizenship, migration, etc.

However, there are a number of other dimensions that are difficult to capture within the left/right and progressive/conservative framework. For example, the nationalist or identitarian dimension is one that occurs in both left-wing and right-wing parties in Europe, although left-wing nationalists are in the minority. The same applies to the rise of populism. This is a style or method, not an ideological framework. In the Netherlands, it occurs on both the right and the left. We must be careful here: ideological systems are interpreted differently in different countries and continents.

In search of ideological features of cultural policy

To arrive at potential characteristics of cultural policy, I draw on a range of sources. There is not much scholarly literature that links ideology and cultural policy in a direct way. One can find interesting material on values that support cultural policy and on justifications of cultural policy (cf. the dilemmas). There are the typologies cited earlier, and there is scattered material that highlights ideological facets. These include publications and books on cultural policy at home and abroad, international professional journals, policy texts, reports, parliamentary papers, articles, and so on. In addition, there is quite a lot of literature that, although it usually does not start from cultural policy, is still useful to conduct cultural policy analyses with, such as the justification theory of Boltanski and Thévenot (1991).

Tendencies in Flemish cultural policy

The focus is on cultural policy in the Flemish Community, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium (hereinafter “Flanders”). The Flemish government has exclusive jurisdiction over culture, alongside education, welfare, economy … I outline the main trends of the cultural policy of the Flemish Community, from 1945 until today. Until the first state reform of 1970, this was still Belgian cultural policy. I describe the trends thematically, but from a historical perspective. I distil the trends from extensive preliminary research. I start from the chronology of cultural policy, including the policy initiatives developed and a political-social sketch for each time period. I analysed the material with attention to social influences, such as economic and social changes, the increase in leisure time, Flemish autonomy, pillarisation1 and depillarisation, the role of cities and municipalities, the growth of free-market cultural activities, increasing cultural diversity, democratization (access to education, culture, etc.). Thus, I identified a number of trends I could identify, including the dominant political-ideological justifications.

In terms of content, one can distinguish three major phases in Flemish cultural policy. Until the end of the 1960’s, we can speak of a cultural policy built on pillarization. The government is restrained, the policy is built on subsidiarity. Since then, this pillarization has been undergoing a gradual but systematic erosion. This policy change is incremental: the old forms and ditto policy continue to exist, but, spurred on by new initiatives, they are supplemented and modified by new policy. That new policy is democratizing, it wants culture to be there for everyone, it is social in the sense that it also contributes to emancipation and empowerment of disadvantaged population groups. This movement is slowly weakening. Cultural policy is undergoing the influence of neoliberalism and, especially since the past two decades, is evolving in that direction.

These substantive phases are traversed and reinforced by two influential institutional shifts. The unitary Belgian model weakens from the 1970s in favour of a federal model in which cultural communities occupy an increasingly important position. The second institutional change is the increasing role of decentralized governments. Cities and municipalities are given an increasingly prominent role.

Sketch of six countries

In order to characterise cultural policy ideologically, it is advisable to gain insight into diverse and varied forms of cultural policy. If you only consider policy in your own country, your perspective will be too narrow.

Since the 1980s, a number of researchers have studied models or typologies of cultural policy. The first were Cummings and Katz (1987). Their typology was based on the criterion of (the degree of) government involvement in the arts. Building on this, Hillmann Chartrand and McCaughey (1989) constructed the first fully-fledged and still most widely used typology. Mulcahy (2017) developed his own typology, linked to major political movements. Other typologies exist, such as those of Rius Uildemolins and Rubio Arostegui (2013), based on the type of welfare state.

To make a comparison with cultural policy in Flanders, I selected the countries mentioned in the international literature as characteristic of the different types. These are the Laissez-Faire (or Facilitator) model, with the United States as its prototype; the Patron State, with Great Britain as its most typical example; the Architect State, with France as its model; and the Social-Democratic model (also known as the Nordic model), with Norway as its example. In addition, I describe illiberal cultural policy, with Hungary and Poland as examples.2 The order is based on the degree of government intervention, from less to more interventionist. I therefore discuss the United States first, followed by Great Britain, Norway, France and finally Hungary and Poland. I will not discuss the Engineer State, as in the former Soviet Union. In order to make useful comparisons with Flemish cultural policy, I will limit myself to types that occur in liberal-democratic countries.

I examine the similar and different characteristics of cultural policy: the extent of government intervention, ideological motivations, the role of arm’s length organizations, the overall goals of cultural policy, the place of those cultural goals in general government policy, the scope of the arts and culture domain, the role of local governments, counties and states (as in the U.S.), the culture budget, access to arts and culture, attention to cultural participation and to the involvement of diverse groups, and some specific characteristics of each of these types-countries. I indicate the political-ideological choices underlying the cultural policies pursued.

Analysis of cultural budgets

In addition, I checked whether the political-ideological drivers are also reflected in the culture budget of the countries mentioned and, of course, of Flanders. This is certainly the case; they are translated into budgetary terms. In Flanders, this results in changing relationships between types of work and disciplines in every policy period. Although they are not spectacular, they are clearly ideologically inspired. Internationally, you can see the ideological choices have a strong impact. Eurostat (2021) figures show this. This concerns expenditure on cultural services in 2019.

We see that Hungary is the European country that spends the highest percentage of its total public budget on culture, followed by Poland (2.5% and 1.8% respectively). This is true at the central level, but is even more pronounced at the local level. Next come the Scandinavian countries (Norway, Denmark) and the Western European countries (Germany, France, the Netherlands, Spain). The latter show a varied pattern (between 1.3% and 0.9%). The lowest percentage is found in the United Kingdom (0.5%).

There are also notable differences between the shares of the central government, the federal states and local authorities. In Spain, for example, the central government is responsible for 14%, the federal states for 19.6% and local authorities for 66.4%. Even in France, traditionally considered a country with a centralised administrative culture, the local share is 71.2%, significantly higher than in Belgium (54.5%).

Norway has the highest per capita spending on culture (451 euros), followed by Denmark (302 euros). France reaches 250 euros, followed by Belgium (210.3) and the Netherlands (208.8). Spain dangles at the bottom with 117.9 euros, just ahead of Poland (104.7) and the United Kingdom (83.4).

Hungary only spends 170.4 euro, even though it has by far the highest percentage of total government spending on culture. The explanation lies in the wide variation in total government expenditure. Total budget expenditure in the Scandinavian countries is much higher per capita than in Poland or Hungary, but the share of culture in total government expenditure is lower in percentage terms.

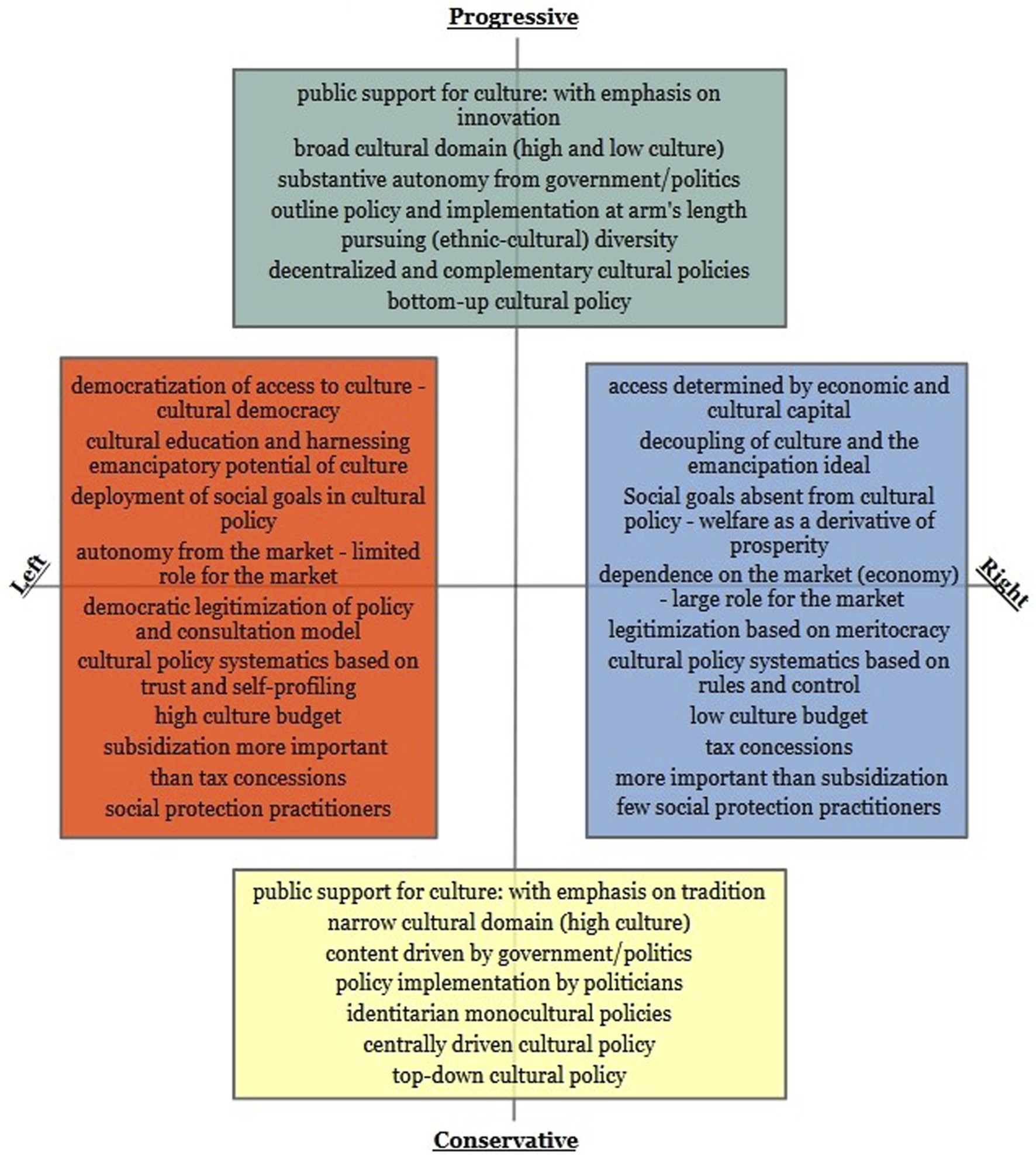

Potential left/right and progressive/conservative features of cultural policy

Based on the many sources cited, I arrived at a structured draft list of potential left/right and progressive/conservative characteristics. This was done deductively. I plotted the characteristics on an x- and y-axis with the dimensions left-right and progressive-conservative, respectively. Above the x-axis are the progressive characteristics, below the x-axis are the conservative characteristics. To the left of the y-axis are the left-wing characteristics, to the right are the right-wing characteristics. If you combine both dimensions (left-right and progressive/conservative) in a system of axes, you get four quadrants: left-conservative, left-progressive, right-conservative and right-progressive.

When working out characteristics, you encounter a tension between specific characteristics of cultural policy and generic characteristics of general policy. The latter group of characteristics often relate to cultural policy, but more to other policy areas. Take for example, the focus on sustainability and ecology, also present in cultural policy, but not specific to it. The theme is mostly found in economic, agricultural or environmental policy. Other examples are digital developments or health issues such as air quality. I have not included such generic features. They may be important, but including them risks snowing under the specifics of cultural policy.

Role of qualitative interviews

I conducted 36 in-depth interviews with key figures. How were the in-depth interviews used? Based on theoretical preliminary research, I designed a structured list of potential left-wing/right-wing and progressive/conservative characteristics. This was therefore done deductively.

This list served as a source for drawing up a questionnaire that I used during interviews and for the accompanying exercise (see below).

These are semi-structured interviews (Ravitch and Carl, 2020). I asked a number of questions that address the various potential characteristics of cultural policy in the form of questions. These are broad, open-ended questions that allow for deeper meanings, motivations and opinions to be explored (Meuleman and Roose, 2015). The interview also contains a few vignettes with statements intended to stimulate discussion on certain themes, including a few current and controversial policy decisions alongside hypothetical and fictional policy decisions. I asked the respondents to respond to these. This method encourages the expression of beliefs.

The interviewees are part of the “communities of meaning” involved in cultural policy. I distinguish four groups. The first group consists of 17 policymakers: all living ministers of culture, every political party represented in the Flemish Parliament, and senior officials from the administration and the funds. The second group consists of 13 people from the cultural field: field workers, artists and managers from support centres and interest groups, from organisations in all sub-sectors. The third group includes two opinion makers/journalists. Finally, four policy researchers: academics from the fields of sociology, cultural management and public administration were also interviewed. I explicitly look for ideological justifications in the categories of politicians and opinion makers. I do this to a lesser extent with people from the cultural field. I do not do this with policy researchers/academics and senior government officials. I disregard their ideological statements.

The most important criterion for selection was the interviewees’ involvement in the cultural world and cultural policy, and their policy-oriented, practical or scientific knowledge of cultural policy. These are people with a broad, reflective outlook. The selection aimed to be as representative as possible. All interviewees are from Flanders and Brussels, with the exception of a former Dutch minister and a French policy researcher. I approached the latter two for comparative reasons; a comparison with other countries is enriching.

Processing the 36 interviews was very labour-intensive. I did this in several steps. First, I made a literal transcription. I then grouped together the answers that belonged to the same theme. For each theme (20), I used search terms (taken from the questions) that made this possible. I used search software for this. I then carried out a second processing of the thematic documents. I filtered the answers of each respondent by removing comments, side remarks, etc., so that only the core answer to the question asked remained. Finally, I examined whether the design system of characteristics of left/right and progressive/conservative cultural policy needed to be adjusted. This led to a grouping of closely related characteristics (16). I also checked whether the characteristics belonged in the left/right category or in the progressive/conservative cultural policy category. I also chose to include a number of clear quotes from interviewees.

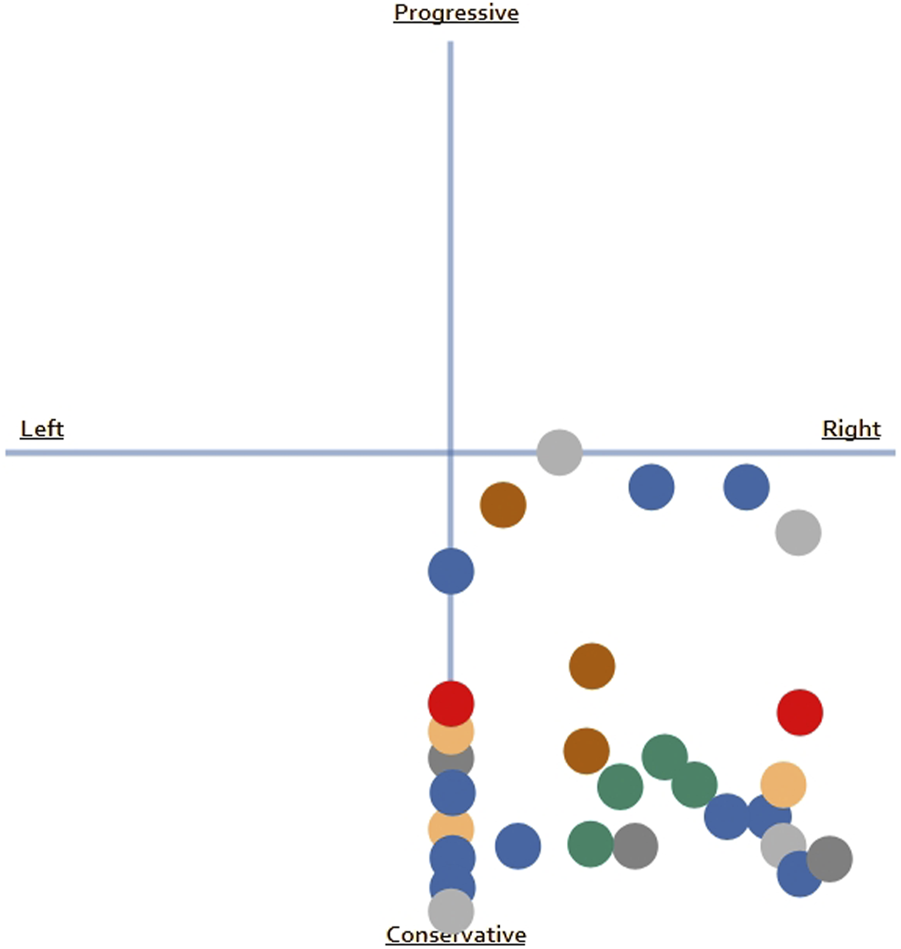

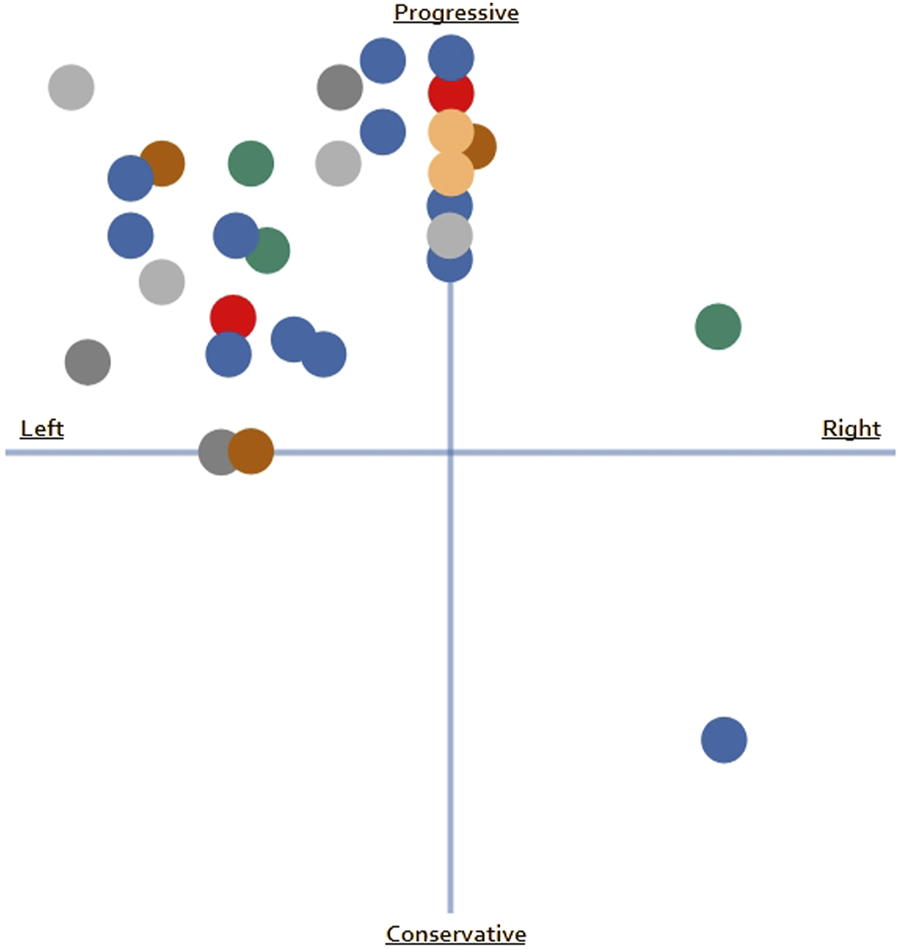

Each interview was followed by an “exercise.” I asked the interviewees to place cards with potential characteristics of cultural policy on the x- and y-axes: ‘Place each characteristic where you think it belongs, regardless of whether you share, support or reject it. This exercise serves a different purpose than the interviews themselves, namely, to verify whether the bipolar characteristics of cultural policy (left/right and progressive/conservative) are correct. I explained the purpose of this exercise to the respondents in advance. I photographed the results of this exercise for each interviewee. I compiled the answers of all interviewees per characteristic in the coordinate system. To do this, I used dots that I placed in exactly the same place as the respondents had done for each theme. This method provides a general picture of the answer to the question of whether the characteristic in question is left or right, and whether it is progressive or conservative. One example: the characteristic “Pursuit of ethnic-cultural diversity in the cultural field” was positioned by almost all respondents in the upper left quadrant of the axis system and can therefore be considered left and progressive.

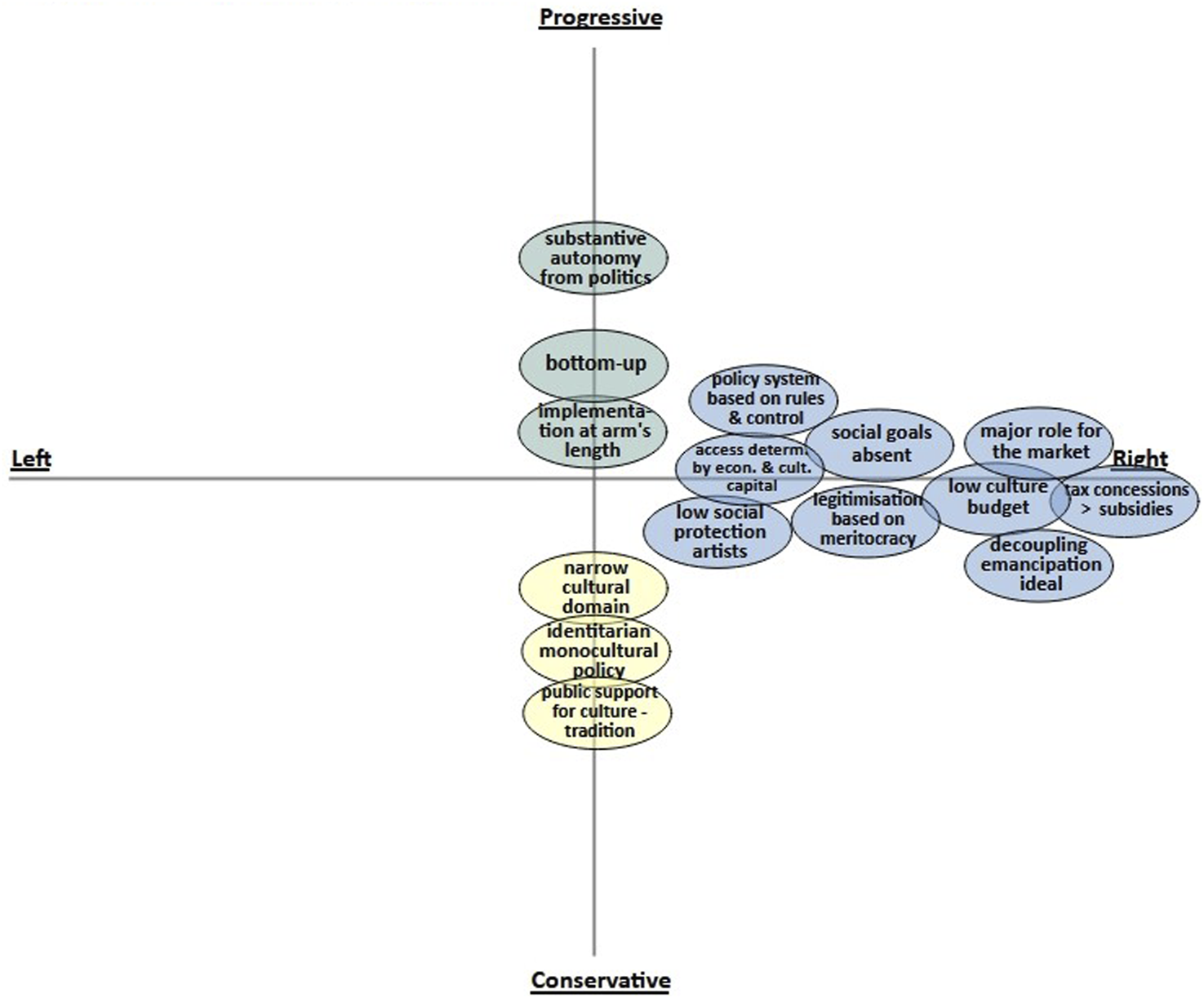

I visualise the characteristics of cultural policy by positioning them in the axis system. I derive the applicable characteristics of cultural policy from the description of each country. By “applicable,” I mean that I include characteristics that most closely correspond to the policy practice in the country on the continuum of binary characteristics. I then place these characteristics in the axis system. The more pronounced a characteristic is, the closer it is to the extreme point of the axis. If a characteristic is less pronounced, I place it closer to the centre of the axis in question.

Results: bipolar characteristics of cultural policy plotted on a system of axes

Thus, I arrived at a final list of characteristics, divided into two categories: left-wing and right-wing characteristics on the one hand, and progressive and conservative characteristics on the other (Table 1). In each category, the characteristics are bipolar. In extreme form they are opposed to each other, but mostly they occur in moderate form. In short, they are continua that allow for nuanced interpretation.

TABLE 1

| Progressive features | Conservative features | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Public support for culture: with emphasis on innovation | Public support for culture: with emphasis on tradition |

| 2 | Broad cultural domain (high and low culture) | Narrow cultural domain (high culture) |

| 3 | Substantive autonomy from government/politics | Content driven by government/politics |

| 4 | Outline policy and implementation at arm’s length | Policy implementation by politicians |

| 5 | Pursuing (ethnic-cultural) diversity | Identitarian monocultural policies |

| 6 | Decentralized and complementary cultural policies | Centrally driven cultural policy |

| 7 | Bottom-up cultural policy | Top-down cultural policy |

| Left-wing features | Right-wing features | |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | Democratization of access to culture - cultural democracy | Access determined by economic and cultural capital |

| 9 | Cultural education and harnessing emancipatory potential of culture | Decoupling of culture and the emancipation ideal |

| 10 | Deployment of social goals in cultural policy | Social goals absent from cultural policy - welfare as a derivative of prosperity |

| 11 | Autonomy from the market - limited role for the market | Dependence on the market (economy)- large role for the market |

| 12 | Democratic legitimization of policy and consultation model | Legitimization based on meritocracy |

| 13 | Cultural policy systematics based on trust and self-profiling | Cultural policy systematics based on rules and control |

| 14 | High culture budget | Low culture budget |

| 15 | Subsidization more important than tax concessions | Tax concessions more important than subsidization |

| 16 | Social protection practitioners | Few social protection practitioners |

Bipolar characteristics of cultural policy.

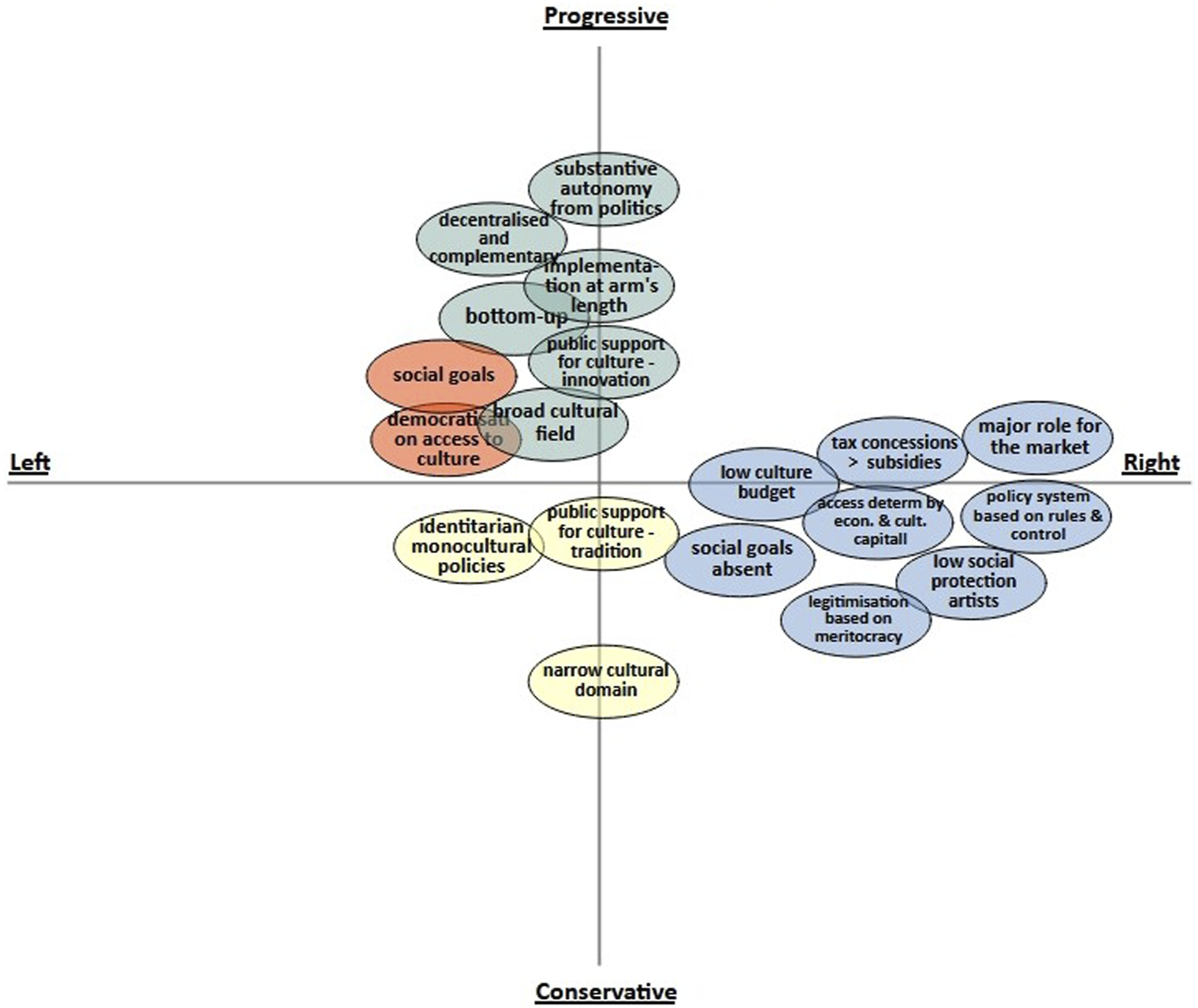

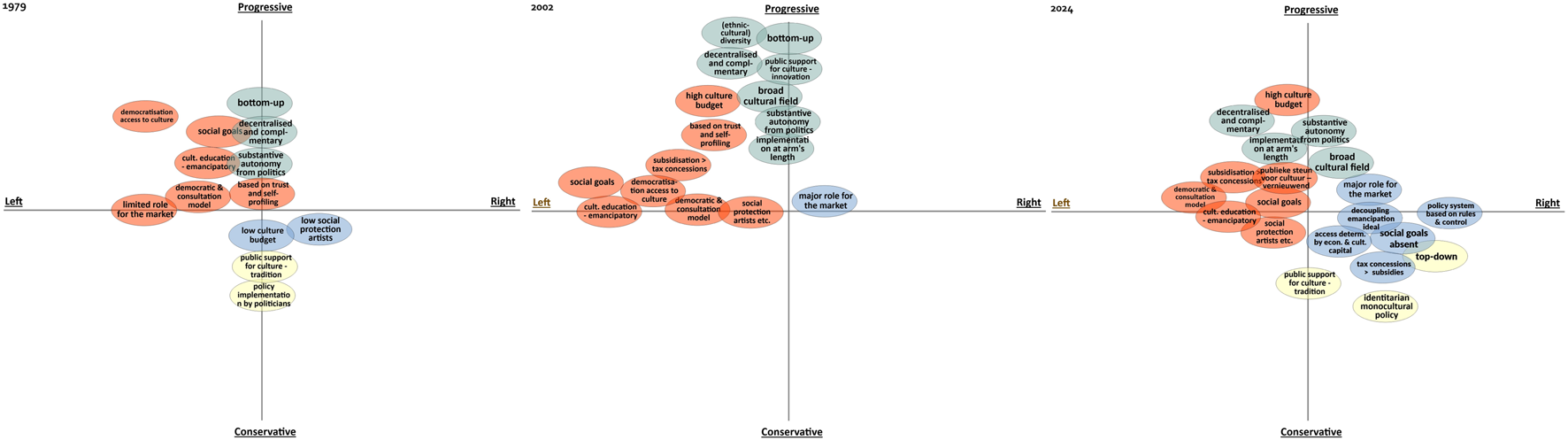

I plotted the characteristics of cultural policy on a system of axes with an x- and a y-axis (Figure 1). The horizontal axis, the x-axis, represents the left-right ideological dimension. On the far left is ideological extreme left and on the right is ideological extreme right.

FIGURE 1

The characteristics of left and right cultural policies and progressive and conservative cultural policies plotted on an x and y axis.

Progressive versus conservative characteristics

In the discussion of the potential characteristics of cultural policy below, several quotes from interviewees are included. The broad study includes more than 10 quotes per characteristic. In this summary, I have limited myself to a number of representative characteristics. For the first characteristic, I have also included two figures showing each respondent’s opinion on this characteristic (the “exercise”). There are figures for each of the characteristics, but there is insufficient space to include them.

Public support of culture: emphasis on innovation or tradition?

Two dimensions come into play here: (1) does cultural policy facilitate innovative or traditional arts and culture or, (2) does it choose challenging or affirming arts and culture (Figures 2, 3). These are two opposites of different natures.

FIGURE 2

Preference for tradition and affirming art and culture.

FIGURE 3

Facilitating innovative and challenging art and culture.

At (2) you feel that this choice is ideologically charged. Challenging cultural expressions question existing values, norms, frames of thought, forms, balances, and so on, often, but not necessarily ideologically inspired.

“Our assessment committees (made up of peers) form the basis of a self-regulating system in which both innovative and less canonical art forms can be picked up. This has led to innovation and radically changed the landscape. The rotten theatre has been tackled,” says Joris Janssens (former director of the Flemish Theatre Institute).

The general tenor from the interviews is clear: a cultural policy owes it to itself to encourage innovation and challenge. What we call traditional in the arts today was often on the side of innovation when it came into being. Economics and science consider research and development very important because a society must always innovate. Remarkably, many explicitly call for a balanced balance, for as rich and as broad a landscape as possible. “Every artist today stands on the shoulders of giants,” is how one respondent put it (Luc Devoldere, former director of Ons Erfdeel/The Low Countries). Quality is the key concept in this context.

Opting for innovative and challenging arts and culture is a progressive principle.

A broad versus a narrow cultural domain

The breadth of the cultural domain refers to the disciplines and forms of work that make up cultural policy. In some countries, this is limited to so-called high culture and the care of (top) heritage. In other countries, and certainly in Flanders, that domain is more extensive and includes the amateur arts, social-cultural work, circus arts, infrastructure, dissemination of culture (such as cultural centres and public libraries), current handling of heritage (movable, immovable and intangible), and so on.

A broad cultural policy ensures that many people can identify with it. It also strengthens support for cultural policy. But many questions also arise. Are we reaching young people today who are in a new way in society and engaged with culture? And also, “(…) the street is coloured, there is a hip-hop world and so much more. If art wants to be meaningful in the future, you have to take it in” (Haider Al-Timimi, artistic director, Antigone). “Young people have different cultural expressions and different experiences of art. You have to keep your finger on the pulse” (Bert Anciaux, former Minister of Culture, social democrat).

A broad cultural domain is very clearly a progressive feature of a cultural policy.

Substantive autonomy vs strong dependence on politics/government

The substantive autonomy of artists (and cultural workers) has been an achievement since modernity.

“Liberal democracy is a crucial basic value. Regardless of whether the policy is rather right or left, as long as there is a framework that is also generally accepted. But if that framework begins to change, you can no longer speak of a legitimate policy. Because then the autonomy of the cultural sector itself and the space for critical action are fundamentally called into question” (Filip De Rynck, Professor of Public Administration).

“It’s not about a mouldy ideal of autonomy, it’s mainly about democratic pluralism.” “In practice, autonomy is permanently under a certain pressure. You have to relate to a subsidizer, who does say you are autonomous, but who at the same time formulates a number of requirements” (Rudi Laermans, Professor of Sociology).

Some, rather on the right side of the political spectrum, put it sharply, such as, for example, this statement, “Truly autonomous artists are those who do not count on these subsidies” (Jan Jambon, former Minister of Culture, Nationalist Party).

Arts and culture are often/sometimes used to achieve policy goals that are extrinsic: economic development, identity goals, social goals and so on. The interviews reveal a dual attitude toward instrumentalization. This attitude is coloured by the goals for which art and culture are instrumentalized: in function of emancipation, in function of social aspects, or in function of elite empowerment or nationalism? This is part of a framework of values. Instrumentalization is especially problematic when it is imposed top-down and the cultural actor is obliged to do so. Instrumentalization is then substantive interference for the sake of a political goal.

In summary, autonomy from government, on the scale between progressive and conservative, is on the progressive side. Government control, on the other hand, is at the other, the conservative pole.

Policy implementation at arm’s length versus policy implementation by politicians

In most liberal-democratic states, the political government outlines policy, while its operationalization is largely outsourced to experts and peers from the cultural domains involved, especially when qualitative assessment underlies the allocation of subsidies.

This is a principle that is generally accepted. The background of this approach is to avoid a direct impact of ideological or political influences on policy implementation. It is also called the Thorbecke principle, after the 19th-century Dutch politician Thorbecke who said that the government should refrain from judging art: “Art is not a government business.” This is the case in Flanders, although there are two models: through independent organizations at arm’s length from the government, and through assessment committees of experts and peers after which the government decides on the basis of their opinions. In Flanders, as in most other Western European countries, “quality” is used as a key criterion for supporting organizations and individuals in the broad cultural world.

“We support this in principle because the alternative is so terrible. Because then you are dependent on the colour of the minister’s shirt for what can or cannot be created. It is a form of state dirigisme, which we do not accept in any other sector” (Jan Jambon). Former Minister of Culture Sven Gatz (liberal party) “believes that decisions should not depend on the taste or whims of elected politicians.”

Policy implementation at arm’s length is widely accepted. No one wants state dirigisme. It is a principle that bears a progressive stamp. However, there are wide variations in the approach. The so-called primacy of politics in making final decisions is stronger in some countries than in others. In illiberal countries like Hungary, politicians largely take control of policy implementation. This is a conservative approach.

Pursuing ethnocultural diversity versus identitarian monocultural policies

Is the pursuit of ethnic-cultural diversity a progressive feature of cultural policy, and is, by contrast, an identitarian monocultural cultural policy - nationalist-inspired - a conservative feature?

The pursuit of diversity involves encouraging diverse cultural practices from practitioners and participants of diverse origins. It also manifests itself in reflecting diversity among staff, in governing bodies and advisory boards, in the distribution of resources, the use of infrastructure, and so on. In a monocultural cultural policy, the policy bets on an identity, imagined or otherwise, for the benefit of an identitarian policy. Cultural expressions that are grounded in one’s own culture, both in art historical perspective and contemporary work, are then supported, to the detriment of diverse cultural expressions that arise on an ethnocultural basis.

Pursuing ethnocultural diversity in the cultural field is a progressive goal. This is evident in the interviews. “The culture houses remain far too white places. With white, educated heads, also a lot of older people,” said Katia Segers (member op Flemish Parliament, social-democrat). Our cultural world is not yet a reflection. (…) There is still a lot of work to do. Just about everyone said that. “My starting point is that culture should be able to be of and for everyone,” said former Dutch Minister of Culture Ingrid van Engelshoven, continuing: “Culture is important for representation and for empathy for the other. Both are important in the context of diversity and inclusion.”

“If you want to receive subsidies, you have to be part of society. The moment you segregate and retreat into something that is de facto outside society, I don’t think you should receive subsidies anymore. In Flanders, there is de facto segregation that goes much further than the cultural sector.” (Filip Brusselmans, Vlaams Belang, far right & nationalist).'

Cultural policy in many countries contributes to the strengthening of national/regional identity. Sometimes this happens very moderately, sometimes it is a dominant justification of the policy. An identitarian cultural policy (domestic), according to the respondents, is right-wing and conservative. In the policy discourse in Flanders, these (identitarian) considerations do become more important, but they are translated into the instruments only to a limited extent. Some, especially from the nationalist corner, defend it, among other things for international promotion of Flanders, for identity building, and so on. This is even more so in Hungary, for example. Still others consider it legitimate, insofar as the cultural sector also claims its territory, its intrinsic value, and insofar as the actors in the cultural field can do their own thing without political interference.

“It is (…) unfortunate that the cultural sector is so uptight about identity. If you look at other regions, such as Catalonia, the Basque Country and Scotland, the cultural sector is still one of the key drivers of those regions” identities. That was also the case in Flanders until the 1980s. Out of a kind of fear, people started to view Flemish identity in a negative light. (Joachim Pohlman, chief of cabinet to Minister Jambon).

However, identity politics is not exclusively conservative. The lack of cultural diversity sometimes leads to “identity politics” along the progressive side.

Decentralized and complementary versus centrally driven cultural policy

In general, decentralization is mainly motivated by the desire to bring the cultural offer and the policy decisions about it closer to the (local) population. The decentralized and complementary local cultural policy (in Flanders) has its origins in the policy of spreading culture, which is decentralized. On the other hand, creation (theatre, music, visual arts) and care of cultural heritage (museums, intangible cultural heritage…) are mainly financed by the central (Flemish) government. The impact is still very high. Countries such as France, the Netherlands, Norway and Denmark have also decentralized some cultural competences.

The fact that a centrally controlled cultural policy, which concentrates power, is conservative is clearly evident in countries such as Hungary. Is decentralisation therefore a progressive dynamic? The survey on local cultural policy in Flanders shows that this is not so clear-cut. There is considerable confidence in the strength of local authorities, but also a certain mistrust of the way in which the Flemish government has approached this decentralisation. However, no one is arguing for centralisation, but rather for a complementary policy that aims to improve quality at the decentralised level through cooperation between policy levels, adequate monitoring and an incentive policy from the Flemish government. “The staffing levels of public libraries have been declining and specific professional knowledge has been deteriorating since decentralisation. Decentralisation seems progressive, but it could be part of a decision to scale back,” (Filip De Rynck).

In essence, a decentralized approach is a progressive feature insofar as governments cooperate, insofar as it does not shift responsibilities to the local level, and insofar as it supports local governments to appoint sufficient experts. Thus, the reality shows neither a distinctly progressive nor conservative picture.

Involving more citizens in the shaping of cultural policy at the local level is easier to achieve than with a central policy. The same applies to democratic control of cultural policy. On the other hand, central governments are better able to ensure equality among citizens. Others note that there is insufficient administrative power and lack of local expertise in many local governments, especially in smaller municipalities.

Bottom-up or top-down

A bottom-up cultural policy manifests itself in a principled willingness to give what develops as free initiative, and is considered valuable, a place in policy. Free initiative is the guiding principle for bottom-up policy. The policy is then open to change driven by evolutions in the cultural field. It is a “follow the actor” system with a corrective and supportive role of government, based on a strong self-profiling of organizations. The philosophy of the 1980s works through: progressive, artistically forward-looking, avant-garde.

“Cultural policy is driven from the bottom up. The government is never going to say: now you have to make that, now you have to create that.” (Jan Jambon and his chief of staff).

This policy approach is therefore a progressive characteristic. This does not mean that the government itself cannot make corrections or take initiatives, i.e., act top-down. How far is that allowed to go? This is, of course, an ideological question. Today, free initiative is supplemented by government initiative in (sub)sectors and for initiatives that the free sector finds difficult to handle. Think of large cultural institutions such as an opera house, a symphony orchestra, a large (repertory) theatre company, important museums, and locally also public libraries and cultural centres … Government initiative occurs almost everywhere, least in Anglo-Saxon countries, strongest in welfare regimes built on powerful roles of governments. France is the most pronounced example of the latter type.

Cultural policy in Flanders is largely bottom-up driven. It comes about through self-profiling of organizations. The government offers a wide range of support mechanisms. Cultural organizations are not subcontractors to the government. Yet a change can be observed, an evolution towards more top-down policy. Various ideological and political motives lie behind this.

Left/right characteristics

Democratization of access to culture versus access determined by economic and cultural capital

Cultural participation research shows how unevenly cultural participation is distributed. The factors are known and located mainly in primary (the family) and secondary (school) socialization, as defined by Bourdieu. Much has been and is being invested in the democratization of access to culture in Flanders. Certainly, on the left, cultural democratization is considered a central mission of cultural policy. The motivation is that participation in culture is a legitimate basic right, a human right and a constitutional right. The cultural sector works with public funds. Then there is a question of legitimacy and everyone must have access to it.

Jan Denolf (Head of the Department of Culture, Youth and Media) says: “It sounds corny, but the right to culture is enshrined in the constitution. That’s one thing. (…) Secondly, we have two hundred years of enlightenment and the development of a model of society that includes the added value of culture for everyone. (…) And thirdly, …) the government intervenes to correct the market.”

Jan Jambon puts it this way: “If by democratisation you mean lowering the threshold, then we think that’s important because it gives more people the opportunity to participate. If by democratisation you mean that no value is attached to the fine arts anymore, then we don’t agree. …) Renewal, innovation, absolutely, but the traditional must also continue to have its place.”

On the right, the importance of democratizing culture is not seen as a priority. Rather, participation is presented as “the chance to participate,” with the underlying idea that if you don’t grab that wreath, the responsibility lies with yourself (the individual). Others point to the cultural sector itself. What happens on the scenes is partly a result of an ideology of art, legitimate high culture. They want to break open that pattern. Among other things, they outline alternatives that belong to the sphere of cultural democracy, to the cultural commons, or the (partial) break with the tradition that only professionals program, often from their own idiom, of what they consider qualitative. Involving audiences and other organizations ensures that the diversity in the program is translated into the diversity of the audience, that they make people feel that this is also a place for them, that they take partial ownership. It is also an interplay between artistic injections and broadening the understanding of art and culture.

There is a strong link between cultural policy and democracy. The cultural sector, along with the media, is a crucial space of publicness and of discussion. And it can represent all possible groups in society artistically and culturally. Participation contributes to inclusion. In addition to the cultural sector, education plays a major role as an engine of participation.

Democratizing access to culture and its availability is a predominantly left and progressive feature.

Cultural education and the emancipatory potential of culture versus disconnection of culture and the emancipatory ideal

It used to be called Bildung. It is about broad personality formation of which aesthetic education is a part. You can also describe it as the development of cultural competence, acquired through education, formation and empowerment. Emancipatory potential refers to the cultural public sphere (Habermas, 1987). The Bildung ideal departed from a normative conception of culture, strongly hierarchical. During the interviews, it was noticeable that precisely this terminology caused a number of respondents to label this characteristic as conservative. The other half calls it a progressive characteristic. They prefer a contemporary concept and interpretation - they refer to a broader and more contemporary concept of culture or talk about the need for cultural and art education, the emancipatory potential of art and culture, both for groups and individuals. Cultural education broadens the range of choice and freedom of choice. It fights exclusion and promotes emancipation. Utilizing the emancipatory potential of culture is ideologically situated on the left.

Joris Janssens: “Cultural education is essential within cultural policy, but also within education: it enables people to become acquainted with a diversity of frames of reference. It is essential for the formation of critical citizens in a changing society.”

This is then contrasted with a cultural policy in which this person-shaping and emancipatory dimension is absent.

Deployment of social goals in cultural policy, whether present or not

Does cultural policy pursue social goals such as promoting social cohesion in communities, social impact in regeneration of deprived neighbourhoods, empowering individuals in poverty? Or does cultural policy not pursue these and is wellbeing seen as a derivative of prosperity? Governments can reinforce social objectives. The specificity of socio-cultural work - the civic perspective - is historically (and also today) based on a social role. The sector explicitly pursues social effects in society. They create opportunities for citizens to do their part in social change.

Rudi Laermans: The democratic horizon has ensured that participation is important in the context of the welfare state’s idea of inclusion. (…) But then you always have the question (…) where do people get the tools to do that? And then there is the issue of social inequality. You have to keep working on that.'

Governments can achieve the social objective in various ways, not by intervening in artistic and cultural content, but by paying policy attention, for example, to geographical distribution, specific actions toward vulnerable target groups, strengthening communities, and so on. Using culture for social purposes is sometimes associated with instrumentalizing culture. Is that true for social purposes? That depends on the function for which art and culture are used. The (social) value of art and culture is broader than its pure intrinsic value.

The use of social goals in cultural policy is a leftist principle.

Autonomy versus market dependence and a large market role

The left/right axis shows substantive and/or artistic autonomy in relation to the market and a limited role for the market on the left, and a large role for the market and a strong dependence on it on the right. The distinction is based on such aspects as the degree of private income of cultural organizations, the patterns of support for and cooperation with the private for-profit sector, the encouragement of entrepreneurship, the support for cultural industries, and the positing of economic objectives (cf. New Public Management).

I approach autonomy in three ways. First, there is the autonomy of artists and cultural workers from the market. Whether you define this ideologically left or right depends on the extent to which the government provides support (subsidies, infrastructure, etc.) for artists and cultural workers so that they can work autonomously from the market. A left-wing cultural policy provides this broadly, a right-wing one limited or not. In addition, I examine whether there are forms of direct or indirect support and regulation for the benefit of commercial actors. Finally, I examine whether aspects of the workings of the cultural industry are given a place in non-profit cultural workings and in their evaluation by governments through cultural policy. On the first aspect, we see that autonomy from the market is not perceived as a major problem in Flanders, as long as there is sufficient government funding. However, some concerns such as the precariat of artists active in this circuit are pointed out.

Patrick Dewael (former Minister of Culture) says: ‘You cannot always express culture in terms of market forces. Fortunately The government does have a role to play. Certain market laws, good management and a focus on the public are not incompatible with artistic goals. …) But if you only pursue market forces, then I am betraying my cultural soul.'

On the second aspect, we generally observe that the market-oriented policy within which commercial actors play an important role is not perceived as problematic but as an enrichment, insofar as there is regulation that combats excesses and the support apparatus purposefully creates added cultural value. This fits in with a government policy that should enable a rich and as diverse offer as possible. A market policy also makes sense to enable Flemish production so that we are not inundated with international, mainly American products. Because of our small scale, quality literature and film are not viable without government support.

Koen Van Bockstal (director of the film and literature funds) states: “If you don’t have a subsidy system for market forces and no framework, you end up in a jungle where the strongest survive. And then, in no time at all, you will see a significant narrowing of the range on offer.”

But is that economic policy or cultural policy? The creative industries should primarily be the object of an economic policy, especially if these actors work purely commercially. But there remains a gray area that does need to be in cultural policy, for film, literature, pop and rock music. In that gray area we see a balancing relationship between economic and symbolic capital.

The third aspect, the intrusion of economic practices into the subsidized field, was commented on during the interviews. The cultural sector needs to be more entrepreneurial, governments often state. The sector is not against it, but it should not be at the expense of subsidies. The sector regrets the one-sided interpretation of entrepreneurship; it is about more than management and finance, but also about personnel management, collaboration, efficiency gains, social connection and strengthening support.

This aspect follows the classic left/right fault line. The left does not reject entrepreneurship, but is reluctant to intrude on economical methods and criteria that underpin government support policies. There is resistance to commodification and commercialization. The right still believes it can do better in this area. Characteristic of right-wing voices, and pronounced neoliberalism, is that the growing impact of the economization of cultural life is not perceived as problematic.

Legitimizing cultural policy: democratic or meritocratic?

Cultural policy is more or less the result of democratic processes of consultation and joint decision-making with actors and their representatives, advisory bodies, local authorities. This is the case with us, but also in countries such as France and the Netherlands. It is limited to the inner crowd. Many comments can be made about the quality of that consultation, about the power relations between the participating actors (the political level, the administration, the strategic advisory council, interest representatives, local authorities, etc.). In Flanders, the consultation model is losing momentum. Yet, lip service is paid to the model by every political group.

Els Buelens (staff member of the Christian Democrats) puts it this way: “There is too little public debate on the subject. Very few journalists follow cultural policy. (…) The public debate on policy priorities is a debate for the inner circle. It does not resonate with the general population. (…) Who should be leading this debate? (…) Academics? Very few academics know anything about cultural policy anymore.”

Cultural policy is never the result of an (ongoing) broad public debate and rarely addresses the essential questions. Nor are efforts made to strengthen it. The creation of cultural policy does not have strong democratic legitimacy. There is clearly an erosion of the processes that could strengthen legitimacy. It is an externalization of increased technocratization and meritocratization of cultural policy. Immediately, one can ask questions about the public support for cultural policy. There is obviously a close connection between democratic processes and the strength of support. The public has limited knowledge of which cultural activities are captured by cultural policy. The political importance of culture is quasi non-existent in elections. Leen Laconte (director of Advocacy Arts Organizations): “I think very few people know what cultural policy is and what it entails.”

Support for and legitimacy of cultural policy is damaged by parts of the political world (especially on the right). They create a negative perception by frequently talking about poor entrepreneurship, poor business management, waste of public funds (subsidies), and so on. Into this fits criticism of the (principle of) granting subsidies.

Cultural policy system based on trust and self-promotion or on rules and control

There is clearly an evolution in the relationship between the Flemish government and the cultural field. We see a standardization of procedures and rules, an increased bureaucracy and control. No one is fundamentally against reasonable control and necessary accountability when working with public funds. It is an evolution that is also visible in other European countries. It shows that distrust is growing and becoming dominant. This is partly due to the dependency relationship between government, the subsidizer, and the field, the subsidy recipient.

Luc Devoldere: “I find nothing worse than the culture of mistrust. The embodiment of this is the judicialisation of our society. You cannot build a political system based on structural mistrust. No, it must be based on trust, but those who are trusted must prove that they are worthy of that trust. That is why evaluation and financial reporting are obviously part of it.”

In cultural policy, the primacy of economic thinking is creeping in deeper and deeper. Public policy, including cultural policy, is moving in a neoliberal direction.

A high or low culture budget

The size of the cultural budget is a financial translation of the importance and intentions of cultural policy. A neoliberal policy very much directs the cultural budget to shrink. A low cultural budget is usually a characteristic of a right-wing policy. A high cultural budget, on the other hand, is a characteristic of a left (and centre-left) cultural policy. A large budget obviously ratifies a dynamic cultural policy. However, there are exceptions. For example, even in some illiberal countries, the cultural budget is high. There it serves an identitarian-nationalist policy.

Bert Anciaux: “When you consider who is involved in that field, I think it’s a very limited intervention. Supporting artists” creativity is essential for social cohesion, for the emancipation of people, but also for socio-cultural work and heritage; all aspects of culture are essential. So I don’t think it’s a luxury at all. (…) If I had to choose, I would remove all subsidies from economic support policy.’

When subsidies and other forms of support are low, dependence on private income is high. I am talking about income from sponsorship, ticketing, patronage, ticket sales, products in museum shops and so on. There is a tendency just about everywhere in Europe to encourage, sometimes oblige, cultural actors to increase the share of these sources of income.

Is market failure a key driver of cultural policy? In countries like the United States and Great Britain, the belief in the power of the market is central to policy. In countries like Norway and France, we see a cultural policy that goes much broader and includes much more than a correction of market failure.

Most respondents argue that the budget in Flanders is low. They consider it an expression of right-wing policies. Cultural budgets in many European countries have been cut at times over the past two decades. Culture is still often perceived as a luxury product.

Does a policy choose subsidization or fiscal instruments

There are roughly two models of financial support: on the one hand, direct support such as grants and indirect forms of support (e.g., through infrastructure, through services such as central library facilities, business support); on the other hand, tax concessions (such as the tax shelter or tax reductions). We see an evolution historically: forms of tax rebates or tax shelters first appeared in Anglo-Saxon countries. In the United States, tax mechanisms are the dominant financing model. In Western European countries, subsidization was long the only model. However, over the past two decades, such tax systems have also been introduced in several Western European countries and have continued to grow (CMS, 2021). The tools include VAT reduction, tax deductions, payroll deductions, and so on. In Belgium, it is mainly about the tax shelter. In many Western European countries, including ours, this or a similar system has been introduced by (centre-)right political administrations. However, (centre-)left-wing majorities, when they took over the political administration, did not change the system.

Joris Janssens puts it this way: ‘You can look at it from a principled and pragmatic point of view. Pragmatically speaking, it provides extra resources for the sector. In principle, it remains tax money that is not subject to a quality test. There are two ways to organise this: either through democratic decision-making processes or through a fiscal mechanism whereby you effectively privatise the financial flow. Personally, I am in favour of the democratic model, but I also see what the tax shelter has brought to the sector.’ Fiscal instruments bring significant sums to the cultural sector, both non-profit and market-oriented actors. This is not contested. But it can affect the policy system (with subsidies).

Bert Anciaux: “It could ultimately lead to the economy determining what can and cannot be developed, and what is art and culture and what is not. That is disastrous, so I am fundamentally opposed to it.”

Fiscal financing methods can be catalogued as ‘right-wing. Subsidization can rather be called ‘left. What is decisive, however, is primarily the relationship between the two financial support mechanisms. Does the total volume of fiscal mechanisms continue to increase, while the total volume of subsidies decreases correspondingly? Does the fiscal mechanism account for a limited portion of the total financial resources accessible to the broad cultural sector, or does the balance between the two systems move in the direction of fiscality? Who are the beneficiaries of fiscal systems, are they the non-profit actors in addition to profit actors? These are concrete parameters that can indicate whether policies are on the right or left side of the ideological spectrum.

The degree of social protection of practitioners

Artists and cultural workers find themselves in a specific professional situation. They have irregular working hours, various assignments, periods without assignments, compensation per performance, uncertainty about structural and project subsidies, etc. This justifies specific forms of social protection. There are various regulations in Europe, with us the artists’ statute is the best known, in addition to regulations in the amateur arts and association work. Current collective bargaining agreements also provide social protection for employees, permanent or otherwise. In such a context, there is a real and proven danger of precariat.

Stephanie D’Hose (Member of Parliament, Liberal): Artists are in a unique situation; they are not paid for rehearsals, reflection, etc. Jan Busselen states: “An artist should be able to have a regular status. However, the issue is that they perform intermittent work, delivering per piece or per performance. There are moments of invisible work.”

Attitudes toward these social protections run along classic ideological distinctions, although there is a broad understanding of the specific work situation. On the right, people argue that the bar for accessing the system is too low, and refer to abuses. It is also questioned by some why social protection is possible for artists and those around them, but not for other professions. On the left, there is a more positive attitude toward this social protection.

The cultural policies of Flanders and five countries ideologically typified

Here I plot the cultural policies of the US, Britain, France, Norway, Flanders, Hungary and Poland on the axis system. I started from the policy as it dominantly occurs in the period described. Of course, a cultural policy evolves. It changes under the influence of a sitting government’s vision of the role of culture and the responsibility that this entails for governments. Nevertheless, over a longer period, one sees a general and continuous line. It usually only bends to a limited extent when a new government is appointed with a different political vision (and ideology). Sometimes, rather exceptionally, it does. In that case, the system of axes reflects the current policy. For the Flemish Community, I made three axes systems that relate respectively to the cultural policy of the years 1979, 2002 and 2024.

In each case, I have included the characteristics, to the extent that they are clearly present in the cultural policy of the country in question, in the figure. Absent characteristics are not included.

First, cultural policy in the United States. The Figure 4 mainly shows that there is no elaborate cultural policy in the US. There are some initiatives, but they are very limited. Cultural policy in the U.S. can be described as right-conservative.

FIGURE 4

Cultural policy in the USA.

The following figure visualizes the cultural policy of the United Kingdom (Figure 5). Cultural policy there is dominantly right-wing. Both progressive and conservative features are present. It is about the systematics of cultural policy and their tradition about policy at arm’s length. There are also policy efforts on democratizing access and pursuing social goals in an urban context. They are not dominant.

FIGURE 5

Cultural policy in the United Kingdom.

Cultural policy in the UK can be described as right-wing, but neither conservative nor progressive.

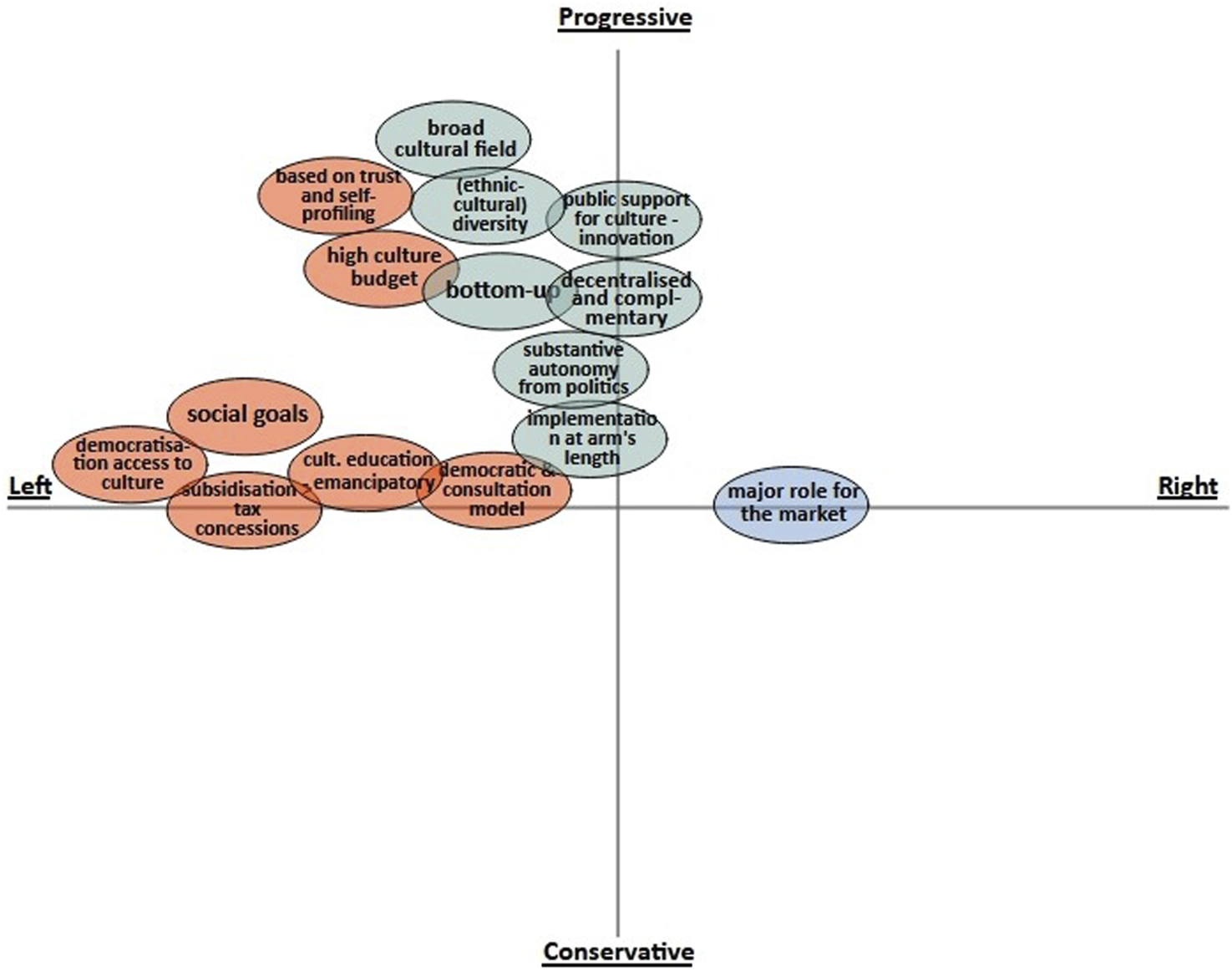

The Figure 6 shows that cultural policy in Norway is of the left and progressive slant. The only dimension that leans to the right is the rather large focus on cultural industries, hence the large role of the market. However, this is balanced by the strong role of governments in Norway.

FIGURE 6

Cultural policy in the Norway.

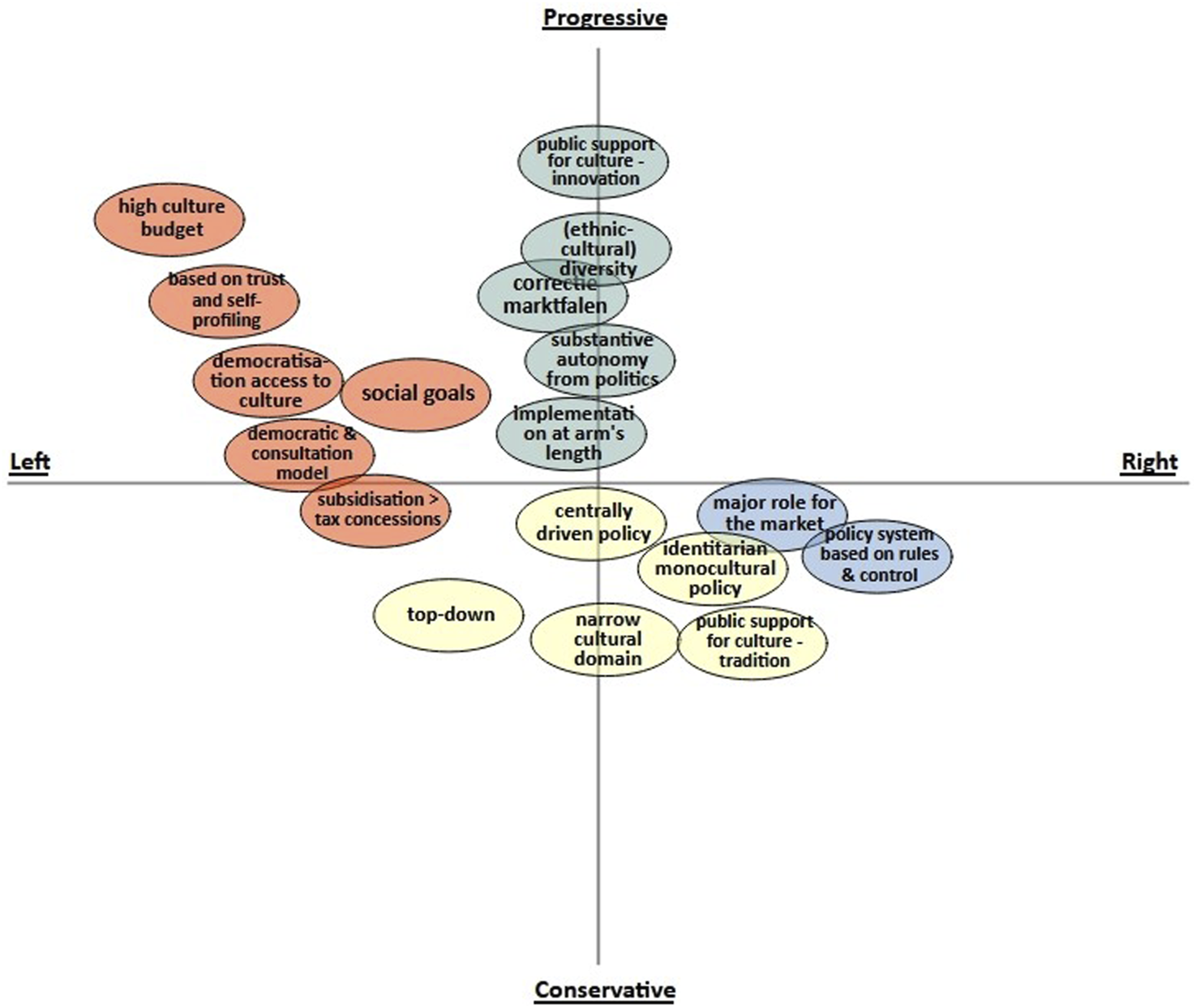

To France, then French cultural policy is etatist (Figure 7). The French state has traditionally held cultural policy tightly in its own hands. This resulted in many initiatives, in the construction of many cultural institutions, in an ample budget, regardless of whether a left-wing or right-wing majority ruled the country. Yet there are anomalous features such as the focus on tradition and the canon and the rise of cultural industries, strongly supported by the government. Cultural policy in France can be described as left (moderate) progressive.

FIGURE 7

Cultural policy in the France.

The system of axes in Figure 8 relates to illiberal countries. It overwhelmingly shows the right-conservative nature of their cultural policies. It is curious, however, that one characteristic appears in the left-progressive quadrant, namely, the high budget for culture. This is striking. It is not a characteristic of progressive policies in those countries, but of policies that are identitarian, where tradition and canon are important, dimensions for which large budgets are allocated.

FIGURE 8

Cultural policies in illiberal countries.

Cultural policy in illiberal countries such as Poland and Hungary can be described as right-wing conservative.

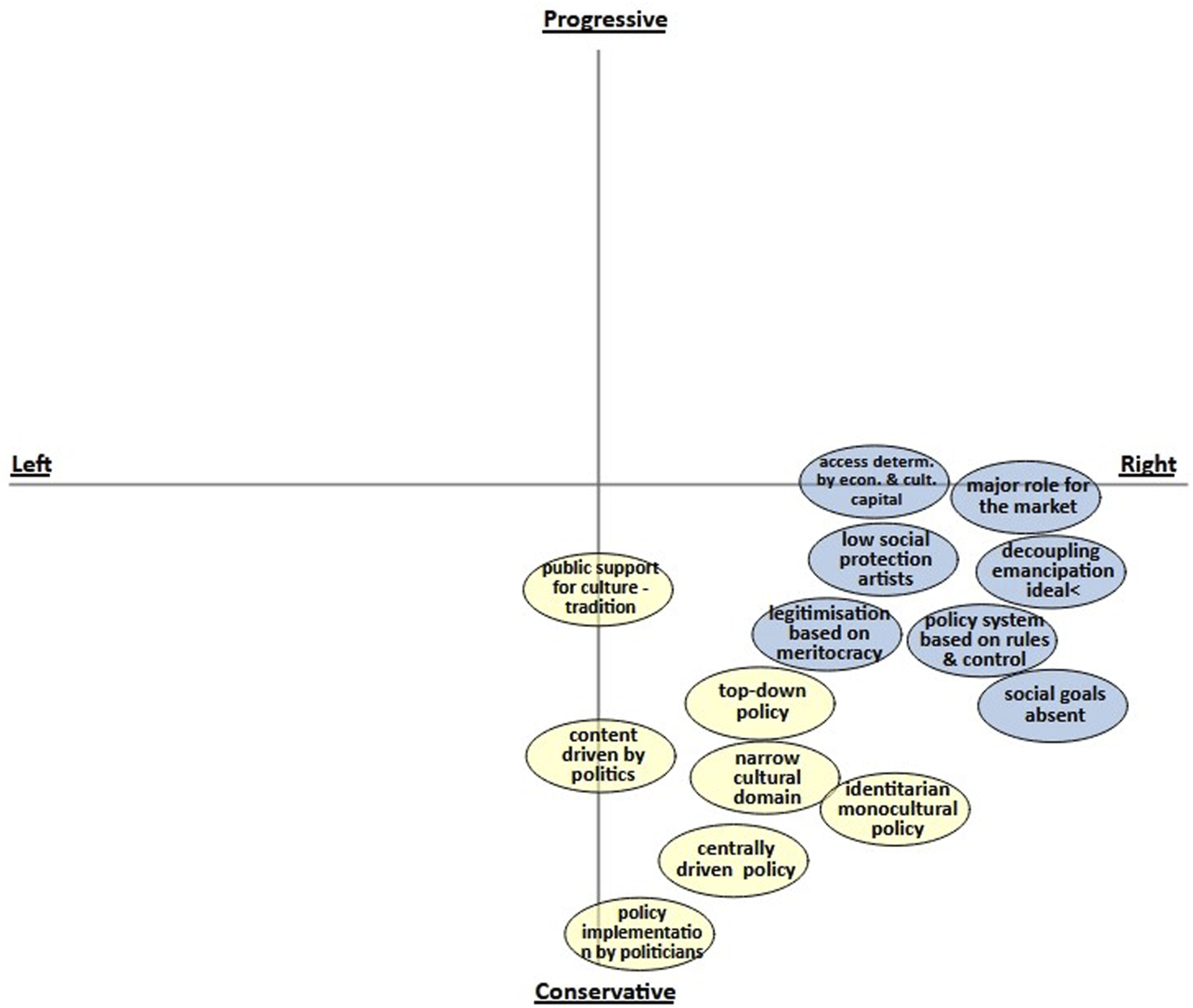

Flemish cultural policy (Figure 9) in 2024 (the right-wing figure) can be described as “centre” (a mix of right and left and a mix of progressive and conservative). Characteristics of right-wing and conservative (identitarian) cut replaced left-wing and progressive characteristics, including the stronger emphasis on the growth of attention to cultural markets, to tradition and to Flemish identities. We also see an increase in control and direction based on New Public Management.

FIGURE 9

Evolution of cultural policy in Flanders in 1979, 2002 and 2024.

If you put the three figures side by side, you can see at a glance the evolution of a centrist policy in 1979, a left-progressive policy in 2002, and again a centrist policy in 2023, but one that is more conservative than the 1979 policy.

Discussion and conclusion

Yes, you can characterize cultural policy ideologically. The categories left/right and conservative/progressive provide a clear framework for positioning characteristics of cultural policy. Placing both categories on an x- and y-axis also clearly shows the relationship between them. Each type of cultural policy takes its own place in this system of axes. If you combine both dimensions (left/right and progressive/conservative) in a system of axes, you get four quadrants.

Progressive-left: pursues cultural emancipation for greater collective wellbeing. Prefers contemporary art and culture, is open to diverse cultural expressions, and guards the autonomy of cultural creators. It interprets cultural policy broadly, much wider than just high culture, and strives for cultural democracy. It works to increase the democratization of access to culture and its proper distribution. The political system implements a cultural policy on outlines and leaves policy implementation (in this case, assessment) to committees or organizations (funds) at arm’s length. It is open to consultation and strengthens the democratic legitimacy of cultural policy.

Progressive-right: loves culture, especially for the sake of economic growth, emphasizes innovation and cultural entrepreneurship, but does not abandon non-profit cultural actors because of market failure. The emphasis is on individual freedom. This streak has much less focus on the democratization of culture. It does distance itself from supporting cultural practice by adopting outline policies and outsourcing their implementation to commissions and/or funds.

Conservative-left: romanticism of local culture and small communities. Sometimes left-wing identity politics and populism. Carries out guiding policies. Knows many guises such as state socialism, populist left in the Netherlands or culturally conservative social democratic and Christian democratic parties, and some communitarians. Democratization is a concern here, though, as is the autonomy of cultural actors from the market. Social goals are part of cultural policy, as the conservative-left wants to pursue the collective good.

Conservative-right: cultural policy for economic as well as identity reasons. Mixture of neoliberalism and neo-nationalism. There is a strong preference for traditional cultural expressions and for affirmative art and culture. The democratization of access to art and culture is not a focus of attention at all, nor is the use of culture for the collective good. That culture has great emancipatory potential does not interest this streak. The democratic legitimization of cultural policy also remains flawed.

Besides ideology, there are more factors that influence planned or implemented policies. A number of contextual factors come into play. The most important is the economic climate, and the resulting financial resources that can be used for cultural policy. But the state of the cultural landscape itself is also important. There are international influences, there may be a pandemic … The more developed the cultural field is, the more attention it demands from cultural policy. Governments must provide answers to the challenges facing the field.

Cultural policy in Flanders is in line with international developments and trends.

Flanders links cultural policy to social and democratic principles. The term “welfare state” captures its spirit. In this type, government is seen as the primary actor for providing social goods, including public culture as a logical extension of the welfare state. Artistic freedom and cultural democracy are paramount. Every citizen has a right to culture. The policy is decentralized, attaches great importance to access to culture, creation, social cohesion, education, and so on. Cultural policy in Flanders therefore leans closely to what the literature calls the Nordic Model. However, Flemish cultural policy also exhibits a number of features of the Architect State, such as France. The government, in this case the Ministry of Culture, plays a determining role. Government funding determines the viability of the organizations, which do function autonomously from the government.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

This study was conducted solely by BC.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

1.^Pillarization: the division of society into groups on philosophical or socio-economic grounds, with the groups organising themselves separately.

2.^Poland and Hungary are formally liberal democratic countries, in practice they have degenerated into autocratic regimes. They are included in the comparison to show the contrast with other liberal democracies.

References

1

Assmann A. (2020). Is time out of joint? On the rise and fall of the modern time regime. New York: Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library.

2

Bell D. Oakley K. (2015). Cultural Policy. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

3

Bobbio N. (1996). Left and right, the significance of a political distinction. Chicago; Cambridge, United Kingdom: The University of Chicago Press Polity Press.

4

Boltanski L. Thévenot L. (1991). De la justification, les économies de la grandeur. Paris: Gallimard.

5

Brunner O. Conze W. Koselleck R. (2004). Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe: Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

6

CMS (2021). “Funding for films, television and other audio-visual works in Western-Europe,” in CMS, legal services EE/G may 2021. Consulted via cms-lawnow.com.

7