Abstract

The comparative case study examines the transformation of the former industrial neighborhoods Savamala (Belgrade) and NDSM Wharf (Amsterdam), both located on riverfronts. By employing a blend of network theoretical and empirical approaches, the research examines governance in urban regeneration programs. The research focuses on three objectives. The first objective is to explain the differences in governance in the regeneration between the two selected case studies. The research thus explores the urban policy formation in both cases: involvement of different stakeholders, the decision-making process, policy goals, and network dynamics. The network of stakeholders includes actors from the public and private sectors. The policy network theoretical and empirical approach is applied to explore the policy-making process. Likewise, the analytical approach explores the social-structural, cultural, and social-psychological contexts in which the actors are embedded, and is applied to explore individual and collective social actions, thus providing an explanation of how those actions have led to the creation of policy outputs. The second objective of the research is to explore policy implementation through the utilization of the network governance approach. The goal is to identify, distinguish, and explore the modes of governance and thus provide an explanation of the power relations in the implementation of regeneration programs in the selected urban environments. The third objective is to question the effectiveness of the governance modes that have been discovered, on two levels, namely, on the network (collective) and community level. This research thus provides answers to whether and why the network and community level goals have or have not been achieved, and to what extent. In the first case study, the research findings suggest the existence of two contrasting policy networks with the different actors’ attributes and structural variables and policy goals behind them. Those policies have also produced two different modes of governance. In the initial phase of the regeneration of Savamala, a fragmented-governed network mode is detected. Whilst, hierarchy is observed in the second phase of the regeneration process. Conversely, in the second case study, a coherency in urban politics can be detected and the modes of network governance are discovered in both phases of the regeneration process. The results of the comparative analysis suggest that network governance modes generate a greater degree of overall effectiveness. Furthermore, the positive outcomes of the regeneration process can be discerned in the urban contexts that support the development of this type of governance structure. This underscores the significance of network governance theory, particularly in the investigation of the regeneration of former industrial riverfronts. Conversely, a governance mode such as hierarchy exhibits limited overall effectiveness, while a fragmented-governed network mode exhibits overall effectiveness to a great extent, but with robust limitations. The former is not effective, as it is not inclusive and relies heavily on the interests of private actors and a handful of political elites, while the latter may lack the stability necessary to engender positive outcomes over the long term.

Introduction

Urban regeneration is a complex process defined by the transformation of areas exhibiting physical, social, and economic decline, encompassing residential, commercial, open, and mixed-use spaces. Regeneration programs aim to revitalize such areas in cultural, social, economic, and physical dimensions. These programs can target entire cities, districts, neighborhoods (Evans, 2005, pp. 959–960), or even specific buildings (Vanolo, 2022). One specific form of this is creativity-led regeneration, which utilizes creativity to revitalize and empower the physical, socio-economic, and cultural qualities of deprived urban neighborhoods (Romein et al., 2013, p. 2). This approach has been explored extensively by scholars, including Zukin (1982), Florida (2005), Evans (2003), Evans (2005) to Grodach (2017) and Vanolo (2017).

Urban regeneration must be examined comprehensively, as it extends beyond spatial transformation to include socio-economic restructuring and governance (Remesar, 2016, p. 7). Governance, in this context, refers to the coordination of social actors toward specific urban goals. This research emphasizes the governance process within regeneration programs, where stakeholders with vested interests in a neighborhood’s development are mobilized and coordinated toward common objectives. The stakeholders interact and influence each other within a network, aligning their individual and collective goals. However, differences in interests (Nagel and Satoh, 2019), aims, resources (Kostica, 2024), and influences from public or private sectors often result in tensions, distrust, and conflicts among stakeholders (Milovanović and Vasilski, 2021), leading to deadlocks, particularly in waterfront regenerations (Lelong, 2014).

These conflicts serve as the starting point for this empirical research, which addresses the complexities of urban governance. To understand governance in different socio-economic and institutional contexts (

Pierre, 2005), this study employs a comparative case study approach, examining Savamala (Belgrade) and NDSM Wharf (Amsterdam). The research focuses on three objectives:

1. Comparing Governance Modes: The first objective is to explain differences in governance approaches in the regeneration of the two selected urban neighborhoods. This involves analyzing urban policy formation, stakeholder involvement, decision-making processes, policy goals, and network dynamics. Stakeholders include public actors, such as political entities and governmental bodies, civil society organizations, individual citizens, and private actors, including economic entities.

2. Exploring Policy Implementation: The second objective is to examine the implementation of urban regeneration policies using a network governance approach. This aims to identify and distinguish governance modes while elucidating the power relations that shape regeneration in each urban setting,

3. Evaluating Governance Effectiveness: The third objective is to assess the effectiveness of the identified governance modes at both the network (collective) level and the community level (Provan and Milward, 1999; Provan and Kenis, 2007). The research seeks to determine whether network and community goals have been achieved and to what extent.

Selection of case studies

The two case studies were selected due to their shared focus on creativity-led urban regeneration and contextual similarities, including historical turning points, location, usage patterns, and existing urban challenges. Both neighborhoods are riverfront industrial areas that thrived until the late 20th century. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, industrial collapse left these areas derelict, resulting in unused industrial heritage. This heritage presented valuable regeneration opportunities through a) vacant industrial spaces suitable for redevelopment, b) advantageous locations—Savamala as an inner-city riverfront area with efficient connections to downtown, and NDSM Wharf with potential connectivity to central Amsterdam, and c) authenticity.

The decline of industry brought similar urban and social problems to both neighborhoods, including marginalization, neglect of industrial heritage, pollution, unemployment, and social and economic deprivation. Local authorities were compelled to address these issues, which initiated the regeneration of both riverfronts. The key driver for riverfront regeneration was the need to reconnect the city with the river, fostering physical and functional transformation that reshaped urban design, visual identity, social life, and local economies. Riverfront areas attract diverse stakeholders who participate in regeneration programs and stand to benefit from their outcomes (Petrović Balubdžić, 2017, pp. 74–75), as explored in subsequent chapters.

In addition to these contextual similarities, comparative research requires variation (Bryman, 2012, p. 75). Differences between the cases, particularly in their political and institutional contexts and the governance of regeneration programs, will be examined through both structural and relational aspects of transformation.

Political and institutional context

The differing political systems between Belgrade and Amsterdam have led to distinct trajectories in urban governance, significantly shaping the regeneration process and its outcomes. Urban governance influences regeneration, impacting both neighborhoods and their communities. Citizen participation, defined as “the process in which members of local communities take part in decision-making in institutions and programs that affect them” (Heller et al., 1984, p. 339), manifests in roles such as advisors, policymakers, or participants in local organizations (Wandersman and Florin, 1990). To promote citizen participation and social capital (Putnam, 2000), urban authorities often implement laws, policies, and incentives (Zientara et al., 2020, pp. 1–5). Engagement, however, depends not only on social capital but also on mechanisms established by authorities to encourage participation (Maloney et al., 2000, p. 803).

Belgrade

Under the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Belgrade had strong citizen participation through a self-government system and integrated planning. However, decisions ultimately served the preservation of the socialist system (Perić and Miljuš, 2017, p. 52). After the breakup of Yugoslavia, the recentralization of power led to top-down decision-making, particularly during the political and economic crises of the 1990s. Private developers and political elites dominated planning, sidelining citizens and interdisciplinary approaches. The new millennium brought a shift towards democracy, with laws supporting political decentralization and citizen inclusion, but in practice, engagement remained weak. Political leaders forged stronger ties with business magnates and foreign investors rather than fostering broad citizen involvement (Perić and Miljuš, 2017; Nedović-Budić et al., 2012). In 2000, Serbia transitioned towards democracy, enacting a new law on local self-government aimed at promoting political decentralization and fostering citizen participation in urban governance. However, in practice, this inclusion remained largely theoretical, as political leaders in the early 21st century cultivated strong ties with domestic business magnates rather than engaging with the public. Likewise, the ruling political elite aligned itself with foreign investors (Perić and Miljuš, 2017, p. 53). Despite this, civil society experienced a renaissance in the early 2000s, contributing to the growth of creative industries, the independent art scene, urban activism, and environmental movements. Nonetheless, they were largely excluded from decision-making processes (Perić, 2019), as demonstrated in the case of Savamala.

Amsterdam

Conversely, the Netherlands transitioned from a top-down governance model to one with growing citizen participation beginning in the 1980s. Political shifts enabled inclusive policy-making experiments at national and local levels, focused on revitalizing neglected neighborhoods and increasing civic responsibility (Michels, 2006, p. 329). In the 1990s and 2000s, policies further strengthened citizen involvement in urban governance, with programs targeting economically depressed areas. Local government efforts integrated artists and neighborhood associations to aid revitalization (Koster, 2014, pp. 54–59 see also Koster, 2015), as seen in the case of NDSM Wharf (Topalović et al., 2003). Amsterdam’s continuity in participatory governance contrasts with Belgrade’s disruption following the collapse of Yugoslavia. While Belgrade struggled with top-down governance, Amsterdam embraced the creative city paradigm around 2000, supporting the creative sector and neighborhood revitalization through public subsidies and affordable workspace policies. The Broedplaats (Breeding Ground) policy, initiated in 1999, exemplified the city’s efforts to support artists and creative entrepreneurs by repurposing former industrial buildings (Oudenampsen, 2007, p. 118). The rise of social movements such as squatter groups influenced policy development, with some successfully advocating for their right to the city (Lefebvre, 1968). These groups contributed to the creation of the Broedplaats policy, addressing the lack of affordable workspace, which had persisted into the end of 1990s (De Klerk, 2017, p. 45, 65). The creative city paradigm gained momentum with Richard Florida’s advocacy in Amsterdam in 2003, which emphasized the social and economic benefits of creativity (Peck, 2012, p. 464). This complemented the inclusive governance approach and the broader urban revitalization of waterfronts on the river IJ (Topalović et al., 2003). The institutional shift in Amsterdam reflected new norms in urban governance and the cultural economy, encapsulated in the city’s motto, “No culture without subculture” (Porter and Shaw, 2013, p. 333).

Comparative analysis

While urban social movements in Amsterdam successfully influenced governance, Belgrade’s socialist system had previously provided affordable housing and workspace, limiting the rise of similar movements. The political and economic crises of the 1990s in Belgrade disrupted these systems, leading to top-down governance and the termination of affordable housing programs (Perić and Miljuš, 2017). Civil society in Belgrade did not evolve into pressure groups capable of influencing urban governance as in Amsterdam. By the 21st century, creative and urban regeneration policies in Belgrade were underdeveloped, and the “creativity” paradigm arrived much later than in Amsterdam, hindered by political elites focused on other priorities.

Governance of regeneration programs

Given the political and institutional differences mentioned, it is unsurprising that disparities in governance arise across the regeneration programs. These variations are particularly evident in both the policy-making processes and the implementation strategies. The approaches adopted for the regeneration programs have resulted in the formation of different governance modes and structures.

Governance can take multiple forms, including hierarchical, market-based, or networked modes (Powell, 1990; Torfing and Sørensen, 2012). Unsurprisingly, these governance modes are observable in urban governance contexts. However, significant distinctions emerge among the three modes in terms of coordination mechanisms, the relationships and communication between actors, decision-making processes, actor preferences, inclusiveness, compliance, and levels of commitment (Torfing and Sørensen, 2012; Bevir, 2013).

In theory, network governance is expected to be more inclusive and democratic compared to other modes (Iacob, 2021, p. 8). However, hybrid forms of governance also exist, where network governance may include hierarchical elements (e.g., command and control mechanisms) depending on the decision-making structure. The effectiveness of any particular governance mode is not easily predictable, as it is influenced by various contextual factors, such as institutional frameworks, economic conditions, and the complexity of the urban problems being addressed (Howlett and Ramesh, 2014).

To examine governance models in urban regeneration, this research employs the network governance theory and empirical framework proposed by Provan and Kenis (2007). Their work has been widely applied in public administration and policy across various fields, from agriculture (Rudnick et al., 2019) to healthcare (Kenis et al., 2019) and urban governance (Ruffin, 2010; Bjorna and Aarsæther, 2010; Blanco et al., 2011).

Provan and Kenis (2007) define network governance as a distinct form of multi-organizational governance with advantages over market- or hierarchy-based forms. Networks are better suited to achieving certain goals that might otherwise be unattainable. These networks typically involve diverse public and private actors, foster enhanced learning, promote more efficient resource use, and improve the ability to address complex problems and deliver services more effectively (Provan and Kenis, 2007, p. 23). While originally focused on health policies and service delivery, this theoretical framework is applicable to other public sectors, including urban regeneration, where it facilitates cross-sectoral collaboration and problem-solving.

In this framework, a network consists of three or more legally autonomous organizations working together to achieve both collective and individual goals. The autonomy of each actor is critical, as it distinguishes networks from hierarchical structures where subordination is present (Nowell and Milward, 2022, p. 11). Interdependence among actors is another defining feature, as no single organization typically has sufficient resources to achieve its goals independently (Torfing and Sørensen, 2012). Therefore, collaboration is necessary to pool resources and coordinate efforts.

identify three basic network governance modes:

1. Participant-Governed Network (Shared-Governance Network): In this decentralized model, all actors are autonomous, and governance is shared among them. Decision-making is collective, with no formal administrative entity. However, certain administrative tasks may be handled by a subset of participants (Provan and Kenis, 2007, pp. 233–235).

2. Lead Organization-Governed Network (Brokered Network): Here, one organization coordinates all key activities and decision-making processes, leading to a centralized and brokered governance structure. Power is asymmetrically distributed, with the lead organization playing a pivotal role in aligning the network’s goals with its own (Provan and Kenis, 2007, pp. 235–236).

3. Network Administrative Organization (NAO)-Governed Network: This mode establishes a separate administrative entity to oversee network governance. The NAO coordinates network activities and serves as a central broker, either mandated by external forces or created by network members themselves (Provan and Kenis, 2007, p. 236).

In addition to these core modes, hybrid forms of governance are often observed, depending on the context and the strategies used in public policy implementation. Other forms of network governance include:

1. Fragmented-Governed Network: This pseudo-network involves independent organizations without a coordinating body. Decision-making occurs organically through informal interactions, with each organization operating autonomously (Rudnick et al., 2019, pp. 119–121).

2. Backbone Organization-Governed Mode: A group of organizations creates a new “backbone” organization to serve as the network leader, enhancing coordination and governance effectiveness (Klempin, 2016).

3. Pseudo-Network Governance: This model resembles a joint venture, where two organizations create a third entity. While it does not involve at least three autonomous actors, it remains more limited in scope than fully developed network governance structures and operates with a more hierarchical governance style (Provan and Kenis, 2007, p. 231; Nowell and Milward, 2022).

Network governance is particularly suited to addressing complex, cross-sectoral “wicked problems” (Kenis, 2017). These highly complex issues, first identified in planning literature (Rittel and Webber, 1973), are difficult to resolve and cut across multiple public sectors (Bevir, 2013; Bevir, 2020). Consequently, network governance is resource-intensive, requiring significant investments of time, human and social capital, and knowledge exchange (Bevir, 2013).

Given the multifaceted challenges facing the urban neighborhoods studied, network governance offers a viable framework for managing regeneration programs. By reviewing these governance modes, this research provides a theoretical and empirical basis for evaluating governance modes in the selected cases.

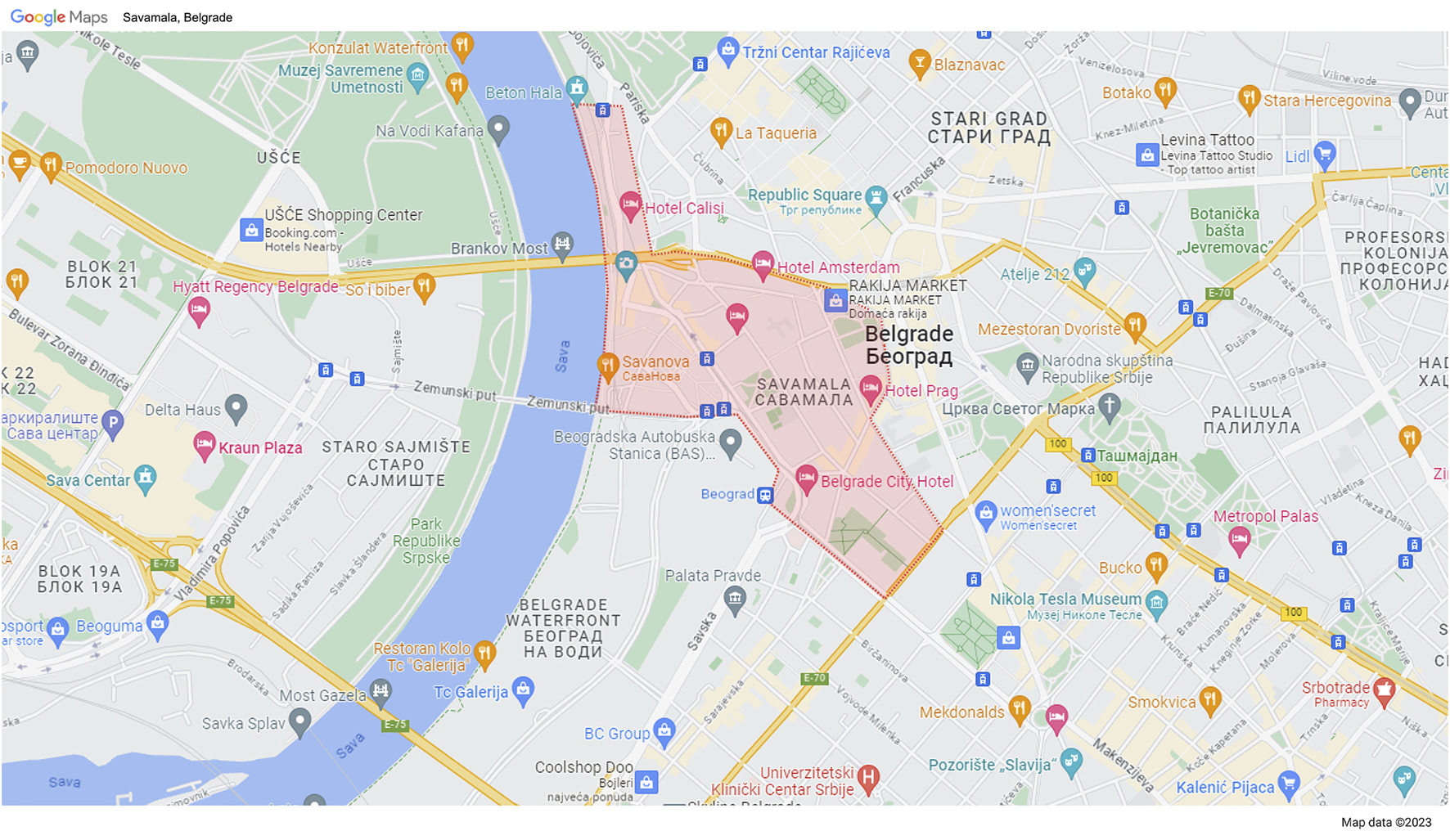

In Belgrade, the initial governance structure for the Savamala regeneration project (see Figure 1) aligned with a fragmented-governed network model. Each organization involved operated with its own governance mechanisms, lacking a central coordinating body. This absence of joint coordination reflected the early policy agenda, which focused on creativity-led regeneration, initiated by the local municipal government. Collaboration between municipal authorities and civil society was envisioned during the early stages of the urban policy-making process. However, by 2015, a shift occurred when new stakeholders entered the scene, forming a new urban policy that prioritized property-led regeneration. This culminated in a strategic alliance between the national government and a foreign investor from the United Arab Emirates, resulting in the establishment of the “Belgrade Waterfront” mega-project. A separate company, “Beograd na Vodi d.o.o.,” was created to coordinate and make decisions regarding the project. This governance mode resembled a joint venture rather than a true network governance structure. Decision-making was centralized in a hierarchical model involving political elites and foreign investors, while the municipal government, civil society, and local residents were largely excluded from the process.

FIGURE 1

A map with the locations of Savamala and the Belgrade waterfront project.

In Amsterdam, the regeneration of NDSM Wharf (see Figure 2) began with an NAO-governed mode. The Kinetic Noord Foundation, alongside working groups from the Art City tenant clusters, managed and coordinated the project, making key decisions. Over time, an external managing director assumed the role of decision-maker. The regeneration of NDSM Wharf was driven by a creativity-led policy agenda for NDSM East, while property-led regeneration was the focus for NDSM West. Unlike Belgrade, urban policy-making in this case involved collaborative efforts between local district, the city, civil society, independent experts from the university and local economic actors.

FIGURE 2

A map with the location of NDSM Wharf in Amsterdam Noord.

In 2003, a commercial agreement between the Noord District and a local developer, Biesterbos, introduced a hierarchical governance mode at NDSM Wharf West. Despite this, the NAO-governed model persisted in NDSM East until 2010, when the NDSM Wharf Foundation was formed to take over part of the governance responsibilities from Kinetic Noord due to its financial difficulties. This new foundation, initiated by the district, reflected a shift in governance. Additionally, new actors from civil society, including those brought in by the City of Amsterdam, began participating in NDSM East. Over time, the governance model transitioned from an NAO-governed mode to a lead organization-governed structure, with the new foundation assuming the role of network coordinator on behalf of the local government. Notably, despite these shifts, the initial policy agenda behind the regeneration of NDSM Wharf remained largely consistent, unlike in Belgrade. Nonetheless, one of the original policy objectives diminished as land was allocated to the developer, and professional management gradually replaced grassroots actors at Kinetic Noord and NDSM Wharf. Despite changes in governance, the policy goals remained consistent throughout both development phases. Similar to the first case study, the national government took interest in NDSM Wharf following increased media attention. The “NDSM Mix to Max” plan, which aimed to create a dense mix of residential, commercial, and creative spaces, was proposed by a local alderman (Topalović et al., 2003, p. 86) back in 2002. However, it faced resistance from the creative community and challenges from the 2008 economic downturn, preventing its adoption as an official policy in Amsterdam.

Theoretical framework

Urban governance in Europe has changed significantly, especially since the 1990s, when global inter-urban competition became a focal point (Swyngedouw et al., 2002; MacLeod, 2011; Pereyra, 2019). Harvey (1989) contends that this shift in governance emphasized entrepreneurialism over managerialism, driven by the need for cities to compete in the global market and stimulate economic growth. This competition has led to strategies such as urban regeneration programs, place marketing, city branding, creative city policies, and flagship megaprojects, which have become central to academic debates in recent decades (Swyngedouw et al., 2002; Evans, 2003; MacLeod, 2011; Grodach, 2017; Vanolo, 2017; Pereyra, 2019). These strategies aim to reshape urban economies and the social, cultural, and physical fabric of cities.

Moreover, new urban politics (NUP) has led to a more diverse range of actors being involved in the planning process, as governments alone lack the resources to realize these strategies. NUP fosters collaboration among stakeholders, including national or supranational private enterprises, public institutions, and civil society, with the goal of fostering personal and community prosperity (MacLeod, 2011; McCann, 2017). This development aligns with the concept of stakeholder networks, which is often examined through network theory (Emirbayer and Goodwin, 1994; Emirbayer and Goodwin, 1996). This research employs network theory as a central lens to explore the social structures emerging during urban regeneration processes in selected cities. Network theory defines networks by two variables: actor attributes and structural patterns of ties between actors (Wasserman and Faust, 1994, p. 29). Actors, represented as nodes, may be individuals or organizations from both public and private sectors, while ties represent various resources (e.g., knowledge, political capital) in the policy-making process. Social network analysis (SNA) is applied to analyze these networks, interpreting social behavior through network structures.

This research also utilizes network governance (Provan and Kenis, 2007; Nowell and Milward, 2022) and policy network perspectives (Kenis and Schneider, 1991) to examine urban networks. The approach of Emirbayer and Goodwin (1994), Emirbayer and Goodwin (1996) is central to analyzing social action in both collective and individual contexts, focusing on the cultural, social-structural, and social-psychological influences on actors. Social action is embedded within relational contexts, including social-structural, cultural, and social-psychological dimensions (Emirbayer and Goodwin, 1994). To understand the social-structural context, SNA is applied, enabling the translation of sociological concepts such as social cohesion, role, and influence into network terms. Key concepts such as centrality (actor’s degree of node), strength of ties, direction of ties, and actors’ roles (e.g., social broker, gatekeeper, and individual role), symmetry or asymmetry, structural hole, and isolate are explored (Wasserman and Faust, 1994).

The cultural context of action pertains to the shared normative commitments and understandings of actors, which shape their possibilities (Emirbayer and Goodwin, 1994, p. 364–367) within the urban planning process. These shared perceptions provide insight into actors’ behavior, with the cultural context informing their motivations and goals in urban regeneration programs. Cultural context is not monolithic (Emirbayer and Goodwin, p. 364), as various aspects of urban development—political, economic, social, cultural, and environmental—inform diverse goals and actions. This research examines cultural context using discourse (Kamalu and Osisanwo, 2015; Goffman, 1979) and frame analysis (Goffman, 1974; Matthes, 2009).

The social-psychological context is linked to individual actors’ meanings and motivations, which are embedded in social ties and influence social action. These meanings include intent, feelings, symbols, and perceptions, and may vary across actors (Ferguson et al., 2017; Fuhse and Mutzel, 2011, p. 1069). Discourse analysis aids in understanding these individual meanings, which are essential to the social-psychological context of action. Furthermore, the strategic orientations of individuals, which guide their choices and actions in specific social settings, are examined (Lelong, 2014; Burt, 1992). These orientations are analyzed through the concept of tertius (Simmel, 1992; Lelong, 2014), offering insight into actors’ preferences and strategies within urban networks. Table 1 summarizes the theoretical concepts discussed in this chapter.

TABLE 1

| Approach | Key authors and year | Key concept/theories | Application in urban governance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociology | Burt (1992); Emirbayer and Goodwin (1994), Emirbayer and Goodwin (1996); Fuhse and Mutzel (2011) | Social network theory, relational sociology, collective action | Social structures, relational contexts in urban planning |

| Psychology | Goffman (1974), Goffman (1979), Matthes (2009) | Frame analysis, discourse analysis | Individual and shared motivations and meanings in decision-making |

| Urban Geography | Harvey (1989); Swyngedouw et al. (2002); MacLeod (2011); McCann (2017); Vanolo (2017); Pereyra (2019) | Urban governance, entrepreneurial governance, global inter-urban competition | Shift from managerial to entrepreneurial city strategies, Urban redevelopment and global city positioning |

| Urban Studies | Healey (1999), Healey (2006), Lelong (2014), Grubbauer and Čamprag (2019) | Collaborative planning, stakeholder analysis, institutional analysis | Inclusion of diverse actors in urban regeneration and balancing competing interests in urban development |

| Network Theory | Granovetter (1973); Wasserman and Faust (1994); Grabher (2006); Ferguson et al. (2017) | Centrality, structural holes, type of ties, strength of ties, individual role | Analyzing power distribution, resource access and influence in networks of stakeholders |

| Network Governance | Provan and Milward (1999); Provan and Kenis (2007); Blanco et al. (2011); Torfing and Sørensen (2012); Nowell and Milward (2022) | Modes of governance, modes of network governance, effectiveness, network structure | Analyzing modes of governance and difference between networks, hierarchies and markets and measuring the effectiveness of governance modes |

A summary of the concepts used to construct theoretical framework.

Methodology

From an epistemological standpoint, this research aligns with the interpretivist tradition, emphasizing that knowledge acquisition and the definition of valid knowledge depend on understanding human behavior. This understanding arises from both the researcher’s external perspective and the perspectives of the study’s participants, situated within a specific context (Bryman, 2012, pp. 27–30). In this case, the focus is on social actors involved in the revitalization of former industrial neighborhoods. The researcher seeks to comprehend their perspectives and interpret their actions accordingly.

The study adopts a constructivist ontological stance. Constructivism posits that meanings are socially constructed through the experiences of actors embedded in particular social contexts and are continuously shaped by social interactions. Social phenomena and categories are thus not fixed but are subject to ongoing revision (Healey, 1999; 2006).

Research design

A comparative research design is employed to examine urban regeneration processes, providing insight into power relations in urban governance and evaluating the effectiveness of governance modes in different urban contexts. In theory, comparative design requires representative cases, meaning that cases are chosen not for being “extreme or unusual,” but because they offer a suitable context for answering the research questions (Bryman, 2012, p. 70). As discussed in the introduction, both cases involve creativity-led regeneration within a transformation process, exhibiting similar usage patterns, locations within the urban fabric, and built environments. Additionally, both cases face comparable urban challenges, such as economic and social deprivation, lack of cultural programs, environmental pollution, and abandoned industrial heritage. These challenges have spurred stakeholders to mobilize resources and pursue entrepreneurial initiatives to address cross-sectoral problems.

Comparative design, however, also seeks to gain deeper insights by contrasting the selected cases. While the cases share similarities, differences in organization of governance are essential for this research. The comparative approach aims to uncover systematic differences in governance modes within regeneration programs and to understand how similar urban phenomena manifest differently across contrasting urban and social contexts (Bryman, 2012, pp. 70–74; Mahoney, 2007).

Research strategy

A mixed-method research approach has been selected as the most appropriate strategy for this study, integrating both qualitative and quantitative methods for data collection and analysis (Hollstein, 2006; 2010). The qualitative component aims to provide a deep understanding of the regeneration process, explain actors’ behaviors (Fuhse and Mutzel, 2011; Fuhse and Gondal, 2015), explore shared and individual meanings (Emirbayer and Goodwin, 1994; DiMaggio, 1997), and investigate network dynamics. This includes reconstructing network structures and examining relations, such as undirected, symmetrical, or asymmetrical ties among actors.

Simultaneously, the quantitative component focuses on reconstructing policy networks by defining tie directions and assessing the positions of actors based on their influence in decision-making processes. Hollstein (2010) suggests that combining qualitative and quantitative data can yield the most comprehensive results. In the context of social network theory, a mixed-method approach aids in case selection and localization by revealing the distribution, conditions, and consequences of social action patterns. Dominguez and Hollstein (2014) further emphasize that qualitative data captures individual actors’ relevance systems more effectively than purely relational data, while combining both qualitative and quantitative network data bridges theoretical perspectives on structure and agency (p. 18). Thus, a mixed-method design enhances result validation and contributes to a more comprehensive and layered understanding of social phenomena (Dominguez and Hollstein, 2014; Bryman, 2012, pp. 627–628), particularly in processes like urban regeneration.

Data collection

To address the research objectives, the following data collection strategies were employed: a) analysis of scientific literature, media coverage, and documents; b) semi-structured and structured interviews; c) observation; and d) field notes.

The initial phase involved analyzing existing literature, media, and documents to identify data and select respondents for interviews (

Wasserman and Faust, 1994;

Dominguez and Hollstein, 2014). Sources included:

Academic publications, master’s theses, and books.

Media coverage: online platforms (websites, online magazines, YouTube channels, documentaries) and offline media (TV shows, newspapers).

Documents such as planning records, laws, expert reports, and policies.

Interviews

In the first phase, purposive sampling was used, strategically selecting respondents relevant to the research topic and goals (Bryman, 2012, p. 418). This sample included a variety of stakeholders involved in the regeneration process, as well as independent experts. The second phase used snowball sampling, with respondents from the first phase recommending others (Bryman, 2012, p. 203, 424). Interviews were semi-structured, allowing flexibility, with open-ended questions. Some interviews were conducted in person, while others were online (via Zoom), by phone, or via email. Structured questions were also included to elicit straightforward answers, particularly to map network relations. Interviews ranged from 30 min to 2 hours, with longer sessions conducted over two phases. A total of 36 respondents participated across both cases, and the interviews were transcribed and analyzed using MAXQDA software. A numerical summary of interviewees from both cases, categorized by sector, is presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2

| Sector | Belgrade | Amsterdam |

|---|---|---|

| Public sector (Local government) | 5 | 2 |

| Public sector (citizens’ and professional associations) | 13 | 8 |

| Public sector (universities and independent experts) | 2 | 4 |

| Private Sector | 1 | 1 |

Number of interviewees in both cities, by sector.

Observation

The researcher acted as a non-participant observer, attending informal discussions but not actively engaging (Bryman, 2012, p. 444). Over 7 years, the researcher visited Belgrade Waterfront’s exhibition stands and discussed the project with staff. Observations focused on the regeneration of industrial heritage, types of cultural or community events, demographic structures, and the area’s integration with the city. Observations and informal conversations contributed to understanding effectiveness of governance modes.

Field notes

Field notes were taken during visits to the neighborhoods and recorded observations on industrial reuse, cultural events, demographic composition, housing types, transportation, and temporary initiatives. These notes were transcribed and analyzed in MAXQDA, contributing to the evaluation of effectiveness in both cases (Bryman, 2012, pp. 450–451).

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted from 2019 to 2023, in parallel with data collection, with both processes continuously referring back to one another (Charmaz, 2000). Qualitative data analysis was performed using MAXQDA software. The majority of collected data, including interview transcripts, documents, and literature, was uploaded to the software and underwent qualitative content analysis. Codes, such as “political capital” or “knowledge exchange,” were created, along with categories, such as “actors’ relations.” Additionally, data from online and offline media coverage, field notes, and observations were integrated as memos and qualitatively analyzed. Besides qualitative analysis, quantitative data analysis was applied to the interview data. This iterative process, where data analysis was conducted alongside data collection, identified gaps and allowed further targeted data collection to create a more comprehensive research narrative. This approach involved “making comparisons,” aiming to select respondents that maximized the chances to fill empirical gaps and uncover variations among concepts (Bryman, 2012, pp. 568–570).

Steps in data analysis

Coding

Codes were employed to organize and label the data (Charmaz, 2000), breaking it into components with specific names. This coding process occurred as the data was collected and entered into the software. Open and focused coding were applied (Bryman, 2012, p. 568), meaning selected parts of transcripts, for instance, were coded according to the theoretical framework. Data was then examined, compared, and categorized into concepts (codes), which were grouped into categories. For example, codes included “power in governance” or “actors’ relations in the policy-making process.”

Theoretical saturation, constant comparison, and interpretation

Sampling continued until the data adequately saturated each category, guided by the theoretical concepts used. This ensured no significant data remained to be collected for a category. Categories were developed in relation to each other, maintaining a close connection between data collection and conceptualization. Phenomena coded under each category were compared and interpreted, enabling theoretical elaboration (Bryman, 2012, pp. 421–426, 568).

Policy networks and (network) governance modes analysis

The analysis of policy networks involved exploring the social-structural, social-psychological, and cultural contexts of action (Emirbayer and Goodwin, 1994, pp. 365–368). The network structure was analyzed using social network analysis (SNA) (Wasserman and Faust, 1994), while the cultural-discursive dimension of networks was examined through discourse (Goffman, 1979; Kamalu and Osisanwo, 2015) and frame analysis (Goffman, 1974; Bryman, 2012, p. 528; Matthes, 2009).

Policy networks

Reconstruction of the social-structural context of action

The social-structural context of action (Emirbayer and Goodwin, 1994, p. 367) was reconstructed by analyzing the network of actors with decision-making power. Political capital was determined by assessing the number of seats held by parties in parliament or council during a policy creation period, based on the analysis of documents and media coverage. Actors were positioned within the policy network according to their decision-making power. This analysis was triangulated with quantitative data, using a diagram to visualize actor influence, where actors closer to the center had greater influence. Actors’ relations were measured through interview data, documents, literature, and media, employing SNA. Relationships were categorized as strong or weak based on duration and intimacy of knowledge exchange, with additional qualitative measurements (e.g., undirected ties, a>b for asymmetry or a = b for symmetry) and quantitative measurements (e.g., degree centrality, directed ties +1 for shared knowledge or political pressure, isolate = 0) assigned.

Reconstruction of the social-psychological context of action

The social-psychological context was reconstructed by examining actors’ positions in the network and their personal meanings (Fuhse and Mutzel, 2011; Fuhse and Gondal, 2015). Personal meanings referred to how actors understood their positions and maneuvered resources to achieve their interests. This was done through discourse analysis of interviews, reports, and media and social network analysis, allowing for an interpretation of the rationale behind actors’ social actions (Bryman, 2012, p. 528). Particular attention was given to understanding the behavior of actors in the position of the third party (Grabher, 2006).

Reconstruction of the cultural context of social action

The cultural context of action, encompassing shared perceptions, values, and attitudes within the social structure, was reconstructed using discourse and frame analysis (Emirbayer and Goodwin, 1994, p. 365; Matthes, 2009; Kamalu and Osisanwo, 2015). Qualitative frame analysis identified stakeholders’ shared perceptions and attitudes about urban development possibilities within the system of rules. Frames, such as economic, social, political, cultural, and environmental, were constructed through inductive analysis, where transcript data and media statements were coded, compared, and grouped into relevant categories.

Reconstruction of (network) governance modes

Qualitative content analysis (Bryman, 2012, p. 291) was used to explore and reconstruct governance modes. The analysis was guided by network governance theory (Provan and Kenis, 2007), examining the involvement of actors, network structure, and authority dynamics. Each mode of governance identified in the case studies was compared with existing literature to determine compatibility. The effectiveness of governance was evaluated by comparing policy goals identified through discourse and frame analysis with regeneration outcomes. The analysis determined the extent to which policy goals were achieved. Community effectiveness was examined by tracing causal mechanisms (Beach and Pedersen, 2013) linking governance modes to outcomes, such as cost to the community, inclusiveness, stakeholder perception that the regeneration program had solved certain urban issues that existed prior to the regeneration, and the cultural and economic impact on the neighborhood (Provan and Milward, 1999). The fulfillment of the selected indicators was qualitatively measured according to the collected data through selected sources and their analysis.

Results

To address the research objectives outlined in the introductory chapter and clarify the comparative logic, three units of analysis have been identified: (a) policy networks and their contexts of action, (b) governance modes, and (c) effectiveness at both the network and community levels.

The first unit of analysis, “Policy Networks and Contexts of Action,” reveals significant differences between the Belgrade and Amsterdam case studies.

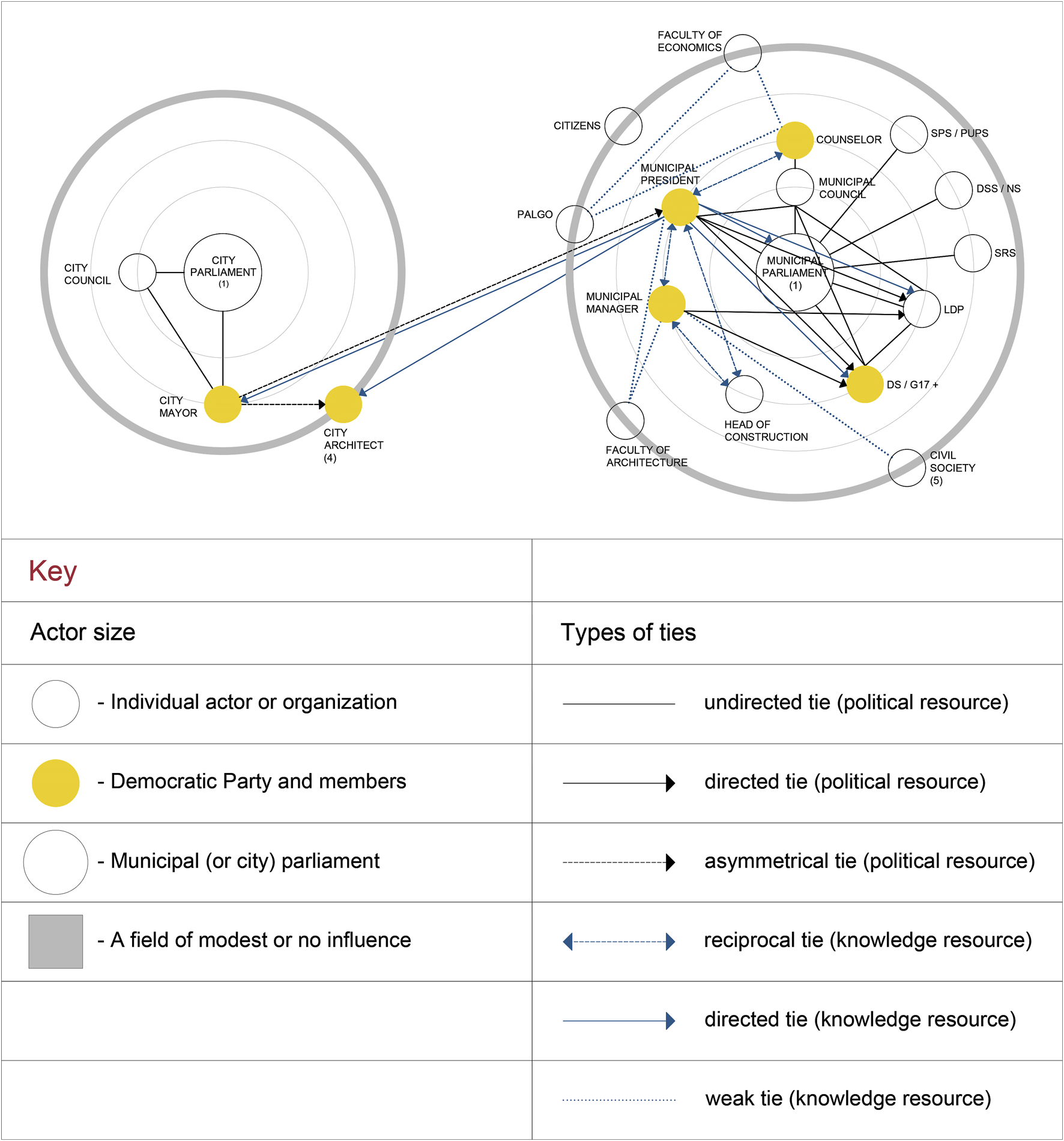

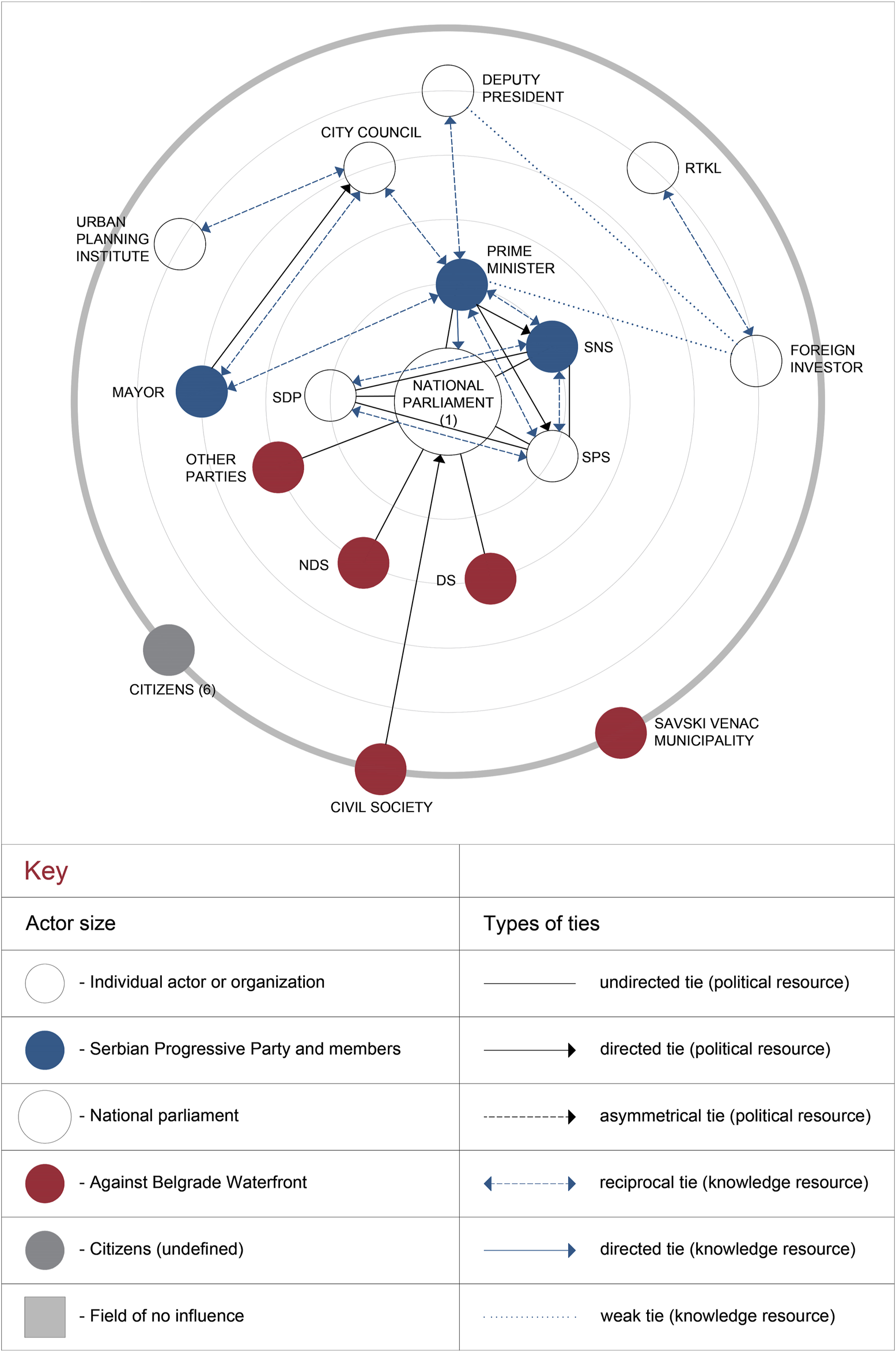

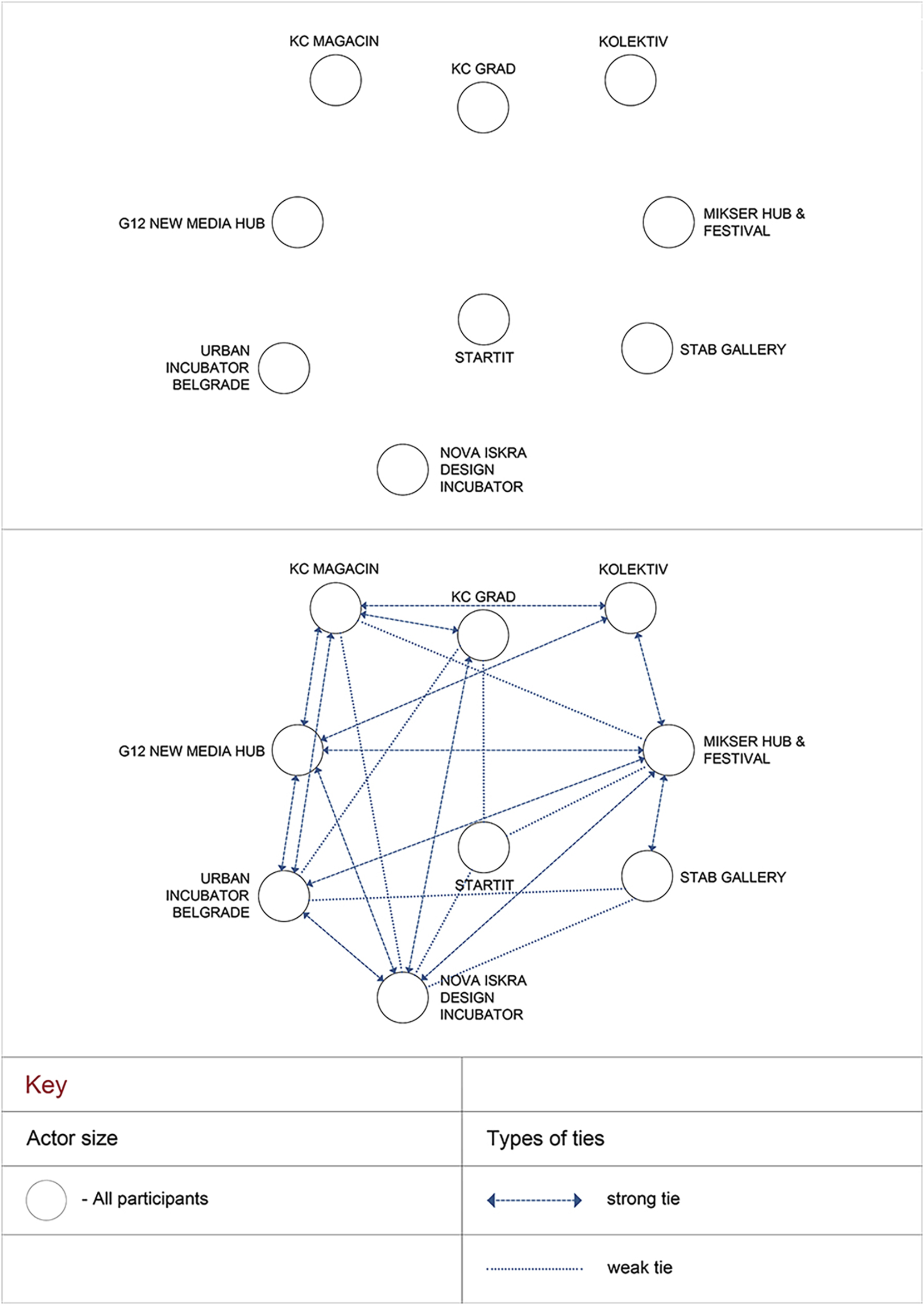

In Belgrade, two distinct policy networks were identified (see Figures 3, 4). Policy network 1 (Figure 3), focusing on creativity-led regeneration, was supported by municipal actors but lacked city-level backing. The municipal manager acted as a gatekeeper, controlling creative projects initiated by civil society. Decision-making in both networks was dominated by political elites, with policy network 2 (Figure 4) involving national-level actors and an economic partner from the UAE, reshaping the urban development agenda for Savamala and the Sava Amphitheatre. The findings suggest a lack of continuity and coherence in Belgrade’s urban policies, exacerbated by limited consultation with civil society and a top-down governance model that marginalized citizen participation.

FIGURE 3

Policy network 1 [diagrams and a key for the explanation of ties].

FIGURE 4

Policy network 2 [the “Belgrade waterfront” network and a key for the explanation of ties].

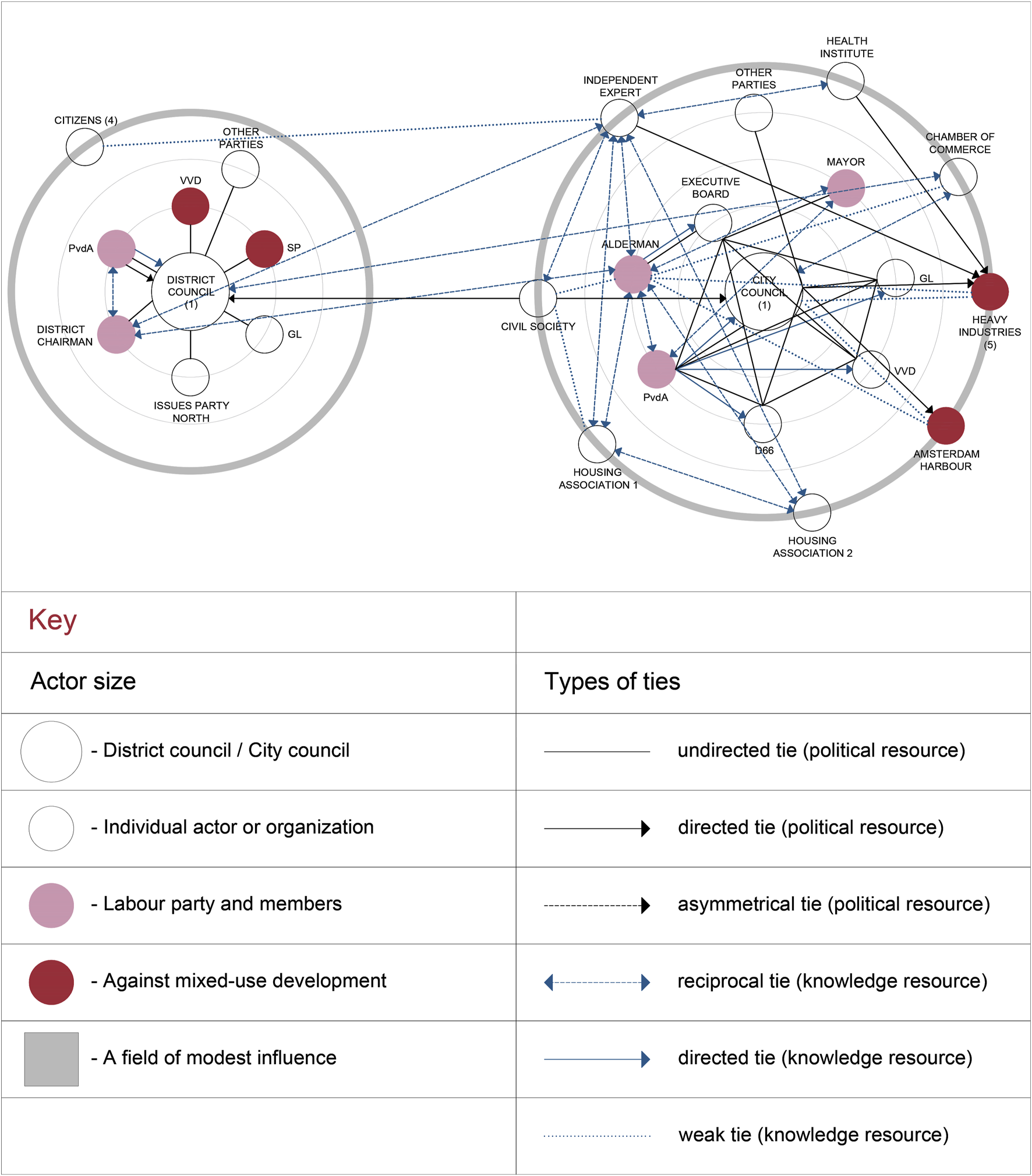

In contrast, the Amsterdam case showcases a more inclusive and coherent policy network (Figure 5). Governance in Amsterdam is decentralized, with decisions involving local and district governments, independent experts, civil society, economic actors, and citizens. The selection process for creative projects, exemplified by the “Art City” initiative at NDSM Wharf, was transparent and participatory. The policy agenda at district and city levels was aligned, supported by extensive action research and the involvement of pressure groups. Amsterdam’s governance model fosters participatory decision-making and reflects shared mental models among key actors, underpinned by strong civil society engagement and a clear regulatory framework that promotes democratic urban development.

FIGURE 5

Policy network 1 [Diagrams and key for the explanation of ties].

The second unit of analysis, “Governance Mode,” reveals contrasting governance structures between Belgrade and Amsterdam.

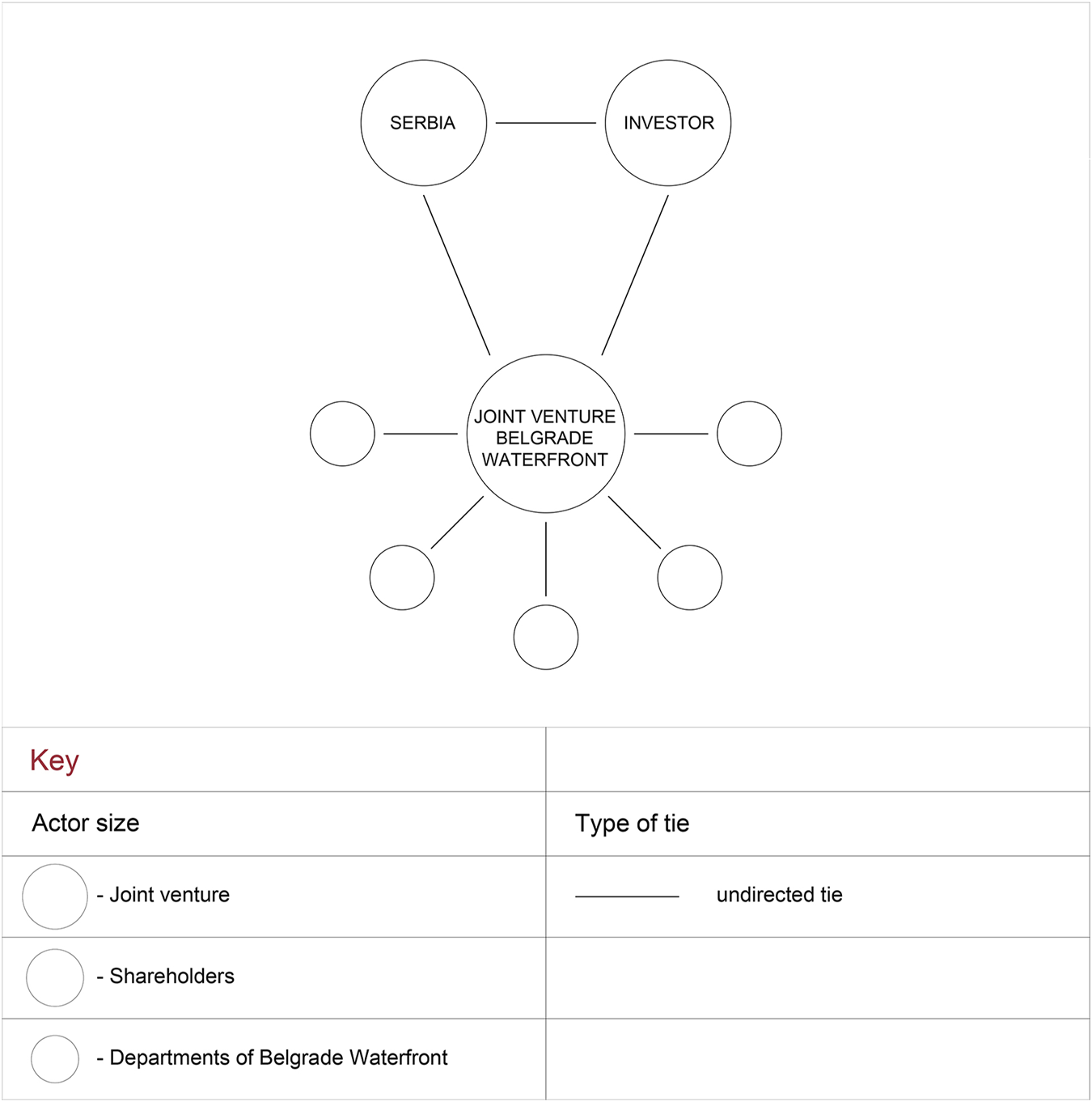

In Belgrade, a fragmented governance network (see Figure 6) was identified in the first case study, characterized by a lack of formal structure, brokerage, and monitoring mechanisms. Collaboration among actors was informal, reflecting limited resources and capacities within the municipality, and reliance on civil society to drive policy implementation. Conversely, the second governance mode (see Figure 7) shows a hierarchical structure, dominated by the Serbian government and a foreign investor responsible for the Belgrade Waterfront project. This governance mode deviates from network governance theory, with market elements evident through the developer’s influence and the Serbian government’s rapid regulatory concessions (Grubbauer and Čamprag, 2019). Governance in Belgrade reflects a top-down decision-making process, without involvement of civil society or local actors, particularly in the second governance mode.

FIGURE 6

Fragmented-governed network (phase 1). Knowledge exchange among independent organizations in Savamala (phase 2).

FIGURE 7

Belgrade waterfront pseudo-network and a key for the explanation of ties.

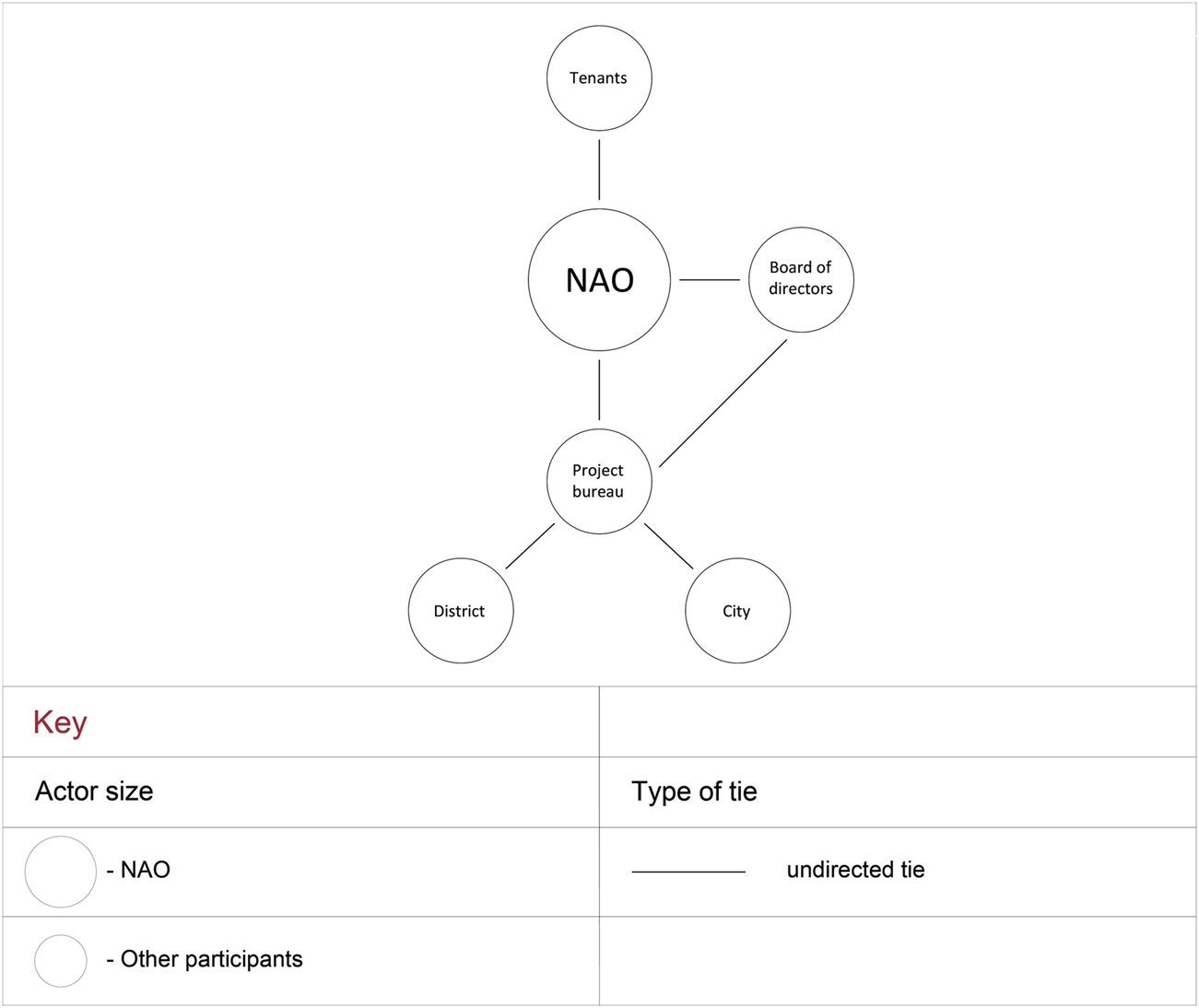

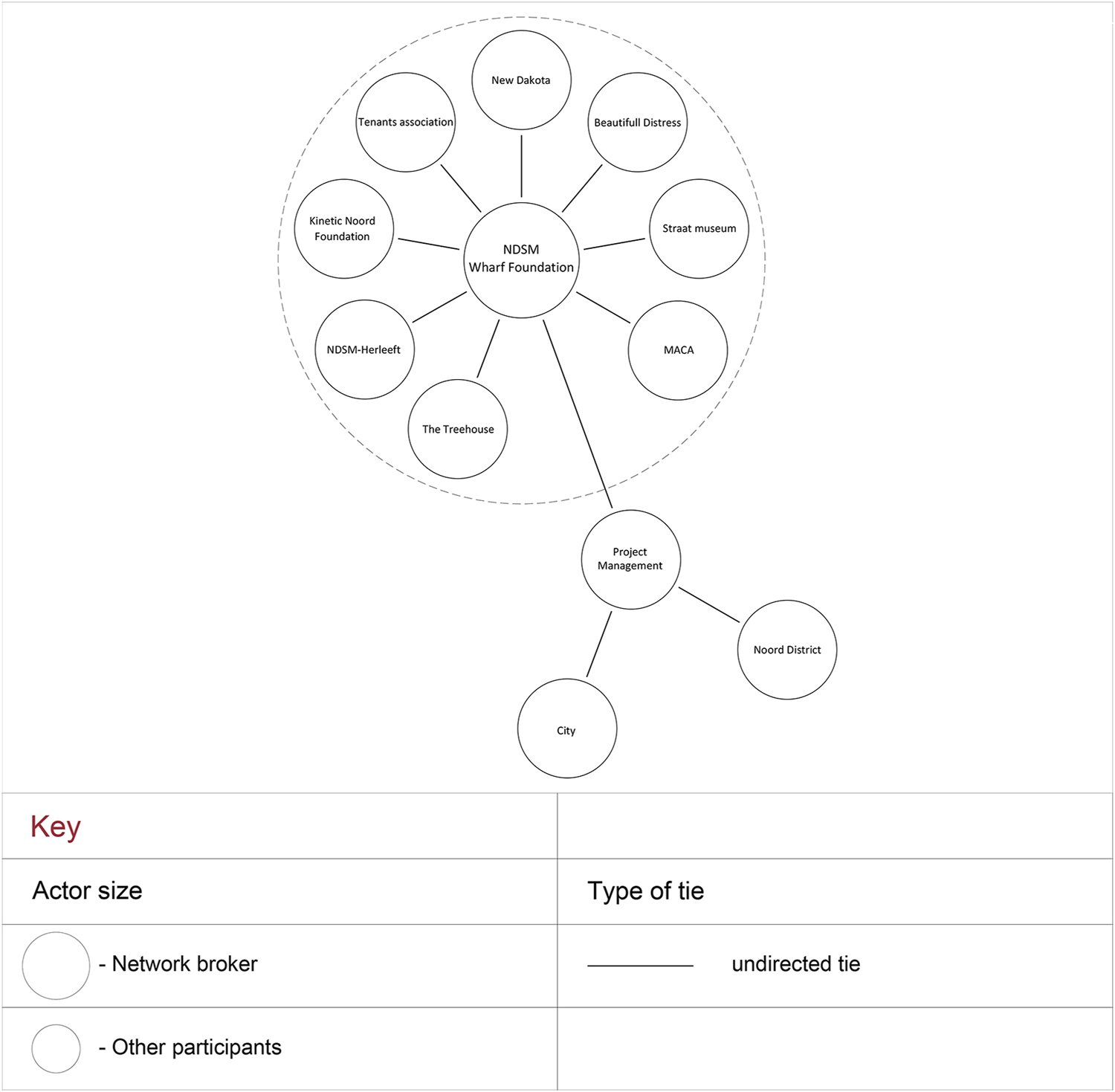

In Amsterdam, a hierarchical governance mode was also observed in NDSM Wharf West, driven by the district government. However, the governance of NDSM Wharf East initially followed a network administrative organization (NAO) mode, coordinated by tenants and managers of Kinetic Noord Foundation (see Figure 8). This later transitioned into a lead-organization governance mode (see Figure 9), with the NDSM Wharf Foundation serving as the network coordinator. Amsterdam’s governance modes differ from Belgrade in their formal structure, inclusion of network brokers, and continuous city monitoring, supported by public investments. Unlike Belgrade, the City of Amsterdam’s stringent regulations and participatory governance framework enabled more robust urban development processes, integrating civil society and ensuring long-term accountability for the regeneration of NDSM Wharf.

FIGURE 8

Network governance (NAO-governed) mode in NDSM wharf East.

FIGURE 9

Network governance mode | lead organization-governed in NDSM East.

The third unit of analysis, “Effectiveness,” assesses the outcomes of the governance modes in Belgrade and Amsterdam.

In Belgrade, the fragmented-governed network mode was initially effective in Savamala, generating positive short-term outcomes for both the network and the community (see Tables 3, 4). However, this mode lacks the formal structure, brokerage, and stability necessary for long-term effectiveness. It is vulnerable to external shifts, such as regulatory changes and political dynamics, and suffers from internal and external legitimacy deficits (Provan and Kenis, 2007), which undermine sustained effectiveness. In contrast, governance mode 2, characterized by a hierarchical structure, achieved only limited effectiveness at both the network and community levels (see Tables 5, 6). Overly ambitious policy goals set by the Serbian government were not fully realized, and the project failed to enhance Belgrade’s regional competitiveness or justify the public interest. Additionally, the Belgrade Waterfront pseudo-network did not leverage the social capital built by the earlier fragmented network. A more participatory governance approach, involving broader public and private actors, could improve long-term effectiveness by creating greater public value. However, the potential to organize governance in a network form in Belgrade remains modest and is unlikely to achieve stability and effectiveness in this context without developed regulations and a shared understanding of more inclusive urban development and collaborative decision-making.

TABLE 3

| Network level goals |

|---|

| ✓ The activation of vacant spaces by civil society with the aim of boosting the local economy, enhancing the position in a local inter-urban competition, and generating revenue for the municipal budget. |

| ✓ Participation of civil society in urban governance and triggering the regeneration of a neglected neighborhood |

| ✓ Empowerment of creative and knowledge-intensive industries |

| ✓ Creating an attractive environment for residents and visitors of Savamala and improving the image of the neighborhood |

| ✓ Making organizations economically sustainable with a focus on audience development and providing services |

| ✓ Attracting professionals from various fields to Savski Venac municipality |

| ✓ Providing cultural content for residents and bonding social capital in Savamala |

| ✓ Urban recycling and reduction of the emission of carbon dioxide |

Achieved goals (policy network 1) Belgrade.

TABLE 4

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Cost to the community | Inclusiveness | Stakeholders perception that the program has solved certain urban issues that existed prior to the regeneration | Cultural impact | Economic impact |

| Level of fulfillment | Low | High | High | High | High |

The level of fulfillment of community effectiveness with evidence.

Indicator (1) Cost to the Community.

Evidence: This regeneration initiative was cost-effective, as it required no local taxpayer funding. The creative sector independently financed space renovations and organized programs. Two organizations received small municipal grants, which were covered by European funds.

Indicator (2) Inclusiveness.

Evidence: The program involved both civil society and private sectors. While the municipality did not participate in governance, it offered public spaces at subsidized rents and provided information when needed. Citizens actively engaged in cultural and educational activities—ranging from IT, courses and urban development conferences to art fairs—organized by civil groups. Participants included students from various academic fields and the wider Belgrade community, with specific outreach to local residents.

Indicator (3) Stakeholder Perception.

Evidence: The regeneration strategies addressed longstanding urban issues in Savamala, such as negative perceptions, industrial heritage decay, cultural deprivation, and economic decline.

Indicator (4) Cultural Impact.

Evidence: The program led to hundreds of cultural events, including exhibitions, concerts, residencies, and festivals that promoted urban activism and community engagement. Educational initiatives, like free IT, lessons, also contributed to cultural enrichment. These activities brought together diverse groups—professionals, students, artists, local residents, and international audiences—fostering inclusivity and community identity, as evidenced by increased positive media coverage.

Indicator (5) Economic Impact.

Evidence: Data suggests growth among local organizations (e.g., KC, grad, Nova Iskra) in terms of employment and collaboration with prominent companies like Telenor and Samsung. increased tourism and investment in hospitality boosted local employment and property values, creating jobs across creative industries, hospitality, and the nonprofit sector.

TABLE 5

| Network level goals |

|---|

| ✓ Establishing a partnership with a foreign investor in order to attract capital investments, boost the construction industry, and attract affluent residents |

| ✓ Demonstration of political power and the ability to boost the national economy, create new jobs and score political points |

| ✗ Development of a megaproject in order to achieve a high ranking of Belgrade within regional inter urban competition Evidence: The development of the mega-project has reached its second phase. However, ranking Belgrade highly within regional inter-urban competition has been limited in the first phases of the development. Additionally, growth in tourism attributable to the project remains unperceivable, and affluent visitors are yet to be lured to Belgrade. Furthermore, the luxury hotel brands promised for the project have not displayed any enthusiasm towards investing in this particular district. The Belgrade Waterfront project has seldom been appraised positively by international media |

| ✗ Generating economic growth and presenting the Belgrade Waterfront as a project of public interest that will become a driver for future developments Evidence: The current phase of development has failed to achieve the desired objective to a larger extent. The transparency regarding the quantum of public funds invested in the infrastructure and the anticipated revenue remains in question. Moreover, the project’s promotion as a public interest initiative appears unjustified, given its primary focus on the construction of up-scale residences and commercial buildings. The project has not become a driver for the city’s future development, as intended. Lastly, the utilization of profits generated from the project lacks transparency |

| ✓ Revitalizing the neglected areas on the Sava riverfront and creating greater opportunities for citizens to utilize the riverfront and the natural environment |

Achieved goals (policy network 2) Belgrade.

TABLE 6

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicators | Cost to the community | Inclusiveness | Stakeholders perception that the regeneration program has solved certain urban issues that existed prior to the regeneration | Cultural impact | Economic impact |

| Level of fulfillment | High | Low | Medium | Low | Medium |

The level of fulfillment of community effectiveness with evidence.

Indicator (1) Cost to the Community.

Evidence: This regeneration initiative has proven costly for local taxpayers, with its benefits largely unsubstantiated. The allocation of prime riverfront land without financial compensation has further strained both city and state budgets.

Indicator (2) Inclusiveness.

Evidence: Governance of the project has been exclusive, with political elites and a foreign corporation assuming control. Other stakeholders, including local communities, have been excluded from decision-making processes and have no role in project oversight.

Indicator (3) Stakeholder Perception of Addressing Urban Issues.

Evidence: While some long-standing urban challenges in Savamala and the Savski Amphitheater—such as its negative reputation—have been addressed, civil society remains largely opposed to the project. Concerns include potential issues like traffic congestion, air pollution, and spatial segregation, indicating divided stakeholder perceptions.

Indicator (4) Cultural Impact.

Evidence: The cultural impact has been limited. Though some collaboration was achieved with local organizations, the cultural offerings, such as art exhibits and festivals, lack the diversity and inclusivity characteristic of earlier regeneration phases. The future opening of a museum in the former Railway Station offers cultural contribution for a general public, but overall programming remains narrow.

Indicator (5) Economic Impact.

Evidence: The project’s economic impact remains unclear, with critical financial details, including the business plan, undisclosed to the public. Though its relevance and public value are questioned, notable impacts include increased land and property values and job creation in construction, architecture, and hospitality.

In Amsterdam, the NAO-governed mode at NDSM Wharf East demonstrated effectiveness to a great extent at the network level, as indicated by the realization of policy goals (see Tables 7, 8). However, community-level effectiveness was limited by poor network governance, resulting in instability and legitimacy issues, compounded by slow development from the private sector. On the other hand, the lead organization-governed mode proved highly effective at both the network and community levels (see Tables 9, 10). This mode allowed the NDSM Wharf Foundation to serve as a network broker, facilitating coordination and communication between stakeholders. The frequent exchange of information between the Management Bureau (City of Amsterdam) and organizations in NDSM East enhanced the effectiveness of the governance mode.

TABLE 7

| Network level goals |

|---|

| ✗ Empowerment of the creative sector to regenerate and transform the image of NDSM and developing a new residential and business area in NDSM West Evidence: This goal has been achieved to a limited extent. The developer did not build the housing units in accordance with the initial plan, but did eventually with an intentional delay |

| ✓ Participation of civil society in activating the vacant industrial buildings and triggering the regeneration of the neglected urban area at the riverfront |

| ✓ Creating an attractive environment for residents and visitors to Amsterdam and improving the image of the neighborhood and the Amsterdam Noord district |

| ✓ Creating jobs in the creative and knowledge-intensive industries |

| ✓ Transforming the former wharf into an area for living, leisure, business, and culture |

| ✓ Attracting professionals from various fields to the NDSM and Amsterdam Noord district |

| ✓ Development according to De Stad als Casco’s philosophy by which the citizens develop the city according to their own needs and are in charge of governance |

| ✓ Creating cultural content for residents and empowering culture and creativity |

| ✓ Urban recycling and regeneration of industrial heritage to provide cultural and economic activities. Establishment of efficient water transportation from the city center to the NDSM. |

Achieved or unachieved goals (policy network 1) Amsterdam.

TABLE 8

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Cost to the community | Inclusiveness | Stakeholders perception that the regeneration program has solved certain urban issues that existed prior to the regeneration | Cultural impact | Economic impact |

| Level of fulfillment | High | Medium | Medium | High | Medium |

The level of fulfillment of community effectiveness with evidence.

Indicator (1) Cost to the Community.

Evidence: This regeneration program has been publicly funded, with approximately €20 million allocated to NDSM East, alongside significant municipal investments in infrastructure across the NDSM Wharf. Additional subsidies were provided to developers for renovating industrial buildings.

Indicator (2) Inclusiveness.

Evidence: NDSM East governance is inclusive, with a network structure engaging various stakeholders and fostering community involvement through cultural events. By contrast, NDSM West governance is less inclusive, comprising only the developer and the city.

Indicator (3) Stakeholder Perception of Addressing Urban Issues.

Evidence: Many of NDSM, Wharf’s urban challenges, such as transport, infrastructure, and reputation, are being addressed through the regeneration. However, some opposition remains, particularly around limited employment options for the working class and a focus on attracting middle-class professionals.

Indicator (4) Cultural Impact.

Evidence: The cultural programming at NDSM, has provided considerable public value to Amsterdam residents, featuring regular events such as the Over’t IJ, theater festival, the Sail Boat Festival, and an art and technology festival. Additionally, the site has achieved heritage protection status as a Rijksmonument, which safeguards significant industrial structures and limits commercial modifications at NDSM East, addressing a key concern for local users.

Indicator (5) Economic Impact.

Evidence: The economic impact is moderate but growing. Around 150 creative businesses have been established at NDSM East, and notable firms, including MTV, discovery channel, and IDTV, have set up offices, stimulating job creation and attracting the hospitality and retail sectors. The area has seen diversified job growth in creative industries, non-profits, and hospitality, contributing to economic revitalization.

TABLE 9

| Network level goals |

|---|

| ✓ Empowerment of the creative sector to regenerate and transform the image of NDSM and developing a new residential and business area in NDSM West |

| ✓ Participation of civil society in activating the vacant industrial buildings and triggering the regeneration of the neglected urban area at the riverfront |

| ✓ Creating an attractive environment for residents and visitors to Amsterdam and improving the image of the neighborhood and the Amsterdam Noord district |

| ✓ Creating jobs in the creative and knowledge-intensive industries |

| ✓ Transforming the former wharf into an area for living, leisure, business, and culture |

| ✓ Attracting professionals from various fields to the NDSM and Amsterdam Noord district |

| ✓ Creating cultural content for residents and empowering culture and creativity |

| ✓ Urban recycling and regeneration of industrial heritage to provide cultural and economic activities. Establishment of efficient water transportation from the city center to the NDSM. |

Achieved goals (policy network no. 1) Amsterdam phase 2.

TABLE 10

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Cost to the community | Inclusiveness | Stakeholders perception that the program has solved certain urban issues that existed prior to the regeneration | Cultural impact | Economic impact |

| Level of fulfillment | High | High | High | High | High |

The level of fulfillment of community effectiveness with evidence (PHASE 2).

Indicator (1) Cost to the Community.

Evidence: The regeneration program continues to be funded from public funds, however with far greater benefits for the city of Amsterdam.

Indicator (2) Inclusiveness.

Evidence: Governance at NDSM East demonstrates high inclusiveness, engaging a range of civil society organizations in network activities. Meanwhile, NDSM, west has attracted additional developers and businesses, increasing its economic footprint.

Indicator (3) Stakeholder Perception of Urban Problem Resolution.

Evidence: Most pre-existing urban issues, such as social and cultural isolation, lack of economic activity, deteriorating industrial heritage, and a poor public image, have been effectively addressed.

Indicator (4) Cultural Impact.

Evidence: The second phase of regeneration at NDSM, wharf east has broadened cultural inclusivity, with organizations focused on film, art, and music establishing a presence. The NDSM, Wharf East Foundation holds monthly stakeholder meetings and aims to incorporate cultural programs appealing to residents of Amsterdam Noord. collaborations with international festivals, including Dekmantel and Amsterdam Dance Event, have further enhanced its cultural offerings, attracting locals, Amsterdam citizens, and international tourists.

Indicator (5) Economic Impact.

Evidence: The economic impact is substantial, with new attractions such as the Street Art Museum and Roc Top educational center, and 380 student apartments established in NDSM, West. NDSM, has achieved international acclaim, housing Amsterdam’s largest breeding ground with 250 tenants, which has spurred interest among affluent residents and led to high-value real estate developments. Luxury accommodations, such as a crane-converted hotel and a nearby Hilton, underscore the area’s transformation. The city and developer, benefiting from increased land values, have turned NDSM, into a coveted neighborhood.

In conclusion, the effectiveness of governance modes in both cities varies depending on the chosen structure and approach. In Amsterdam, the hierarchical governance at NDSM West and the lead-organization model at NDSM East complement each other, achieving policy goals while balancing creative and commercial interests. The creative developments at NDSM East enhanced the neighborhood’s cultural identity, while the commercial activities at NDSM West supported economic growth. This contrasts with Belgrade, where governance has been hindered by a lack of citizen participation, stability, and effective resource allocation.

Discussion

The findings suggest that civil society possesses both the interest and ability to mobilize knowledge and social capital, which can contribute to the revitalization of former industrial neighborhoods and ultimately result in positive outcomes in the regeneration of riverfronts. The results align with the perspectives that advocate for the benefits of the creative sector in enhancing urban economies. The creative sector generates public value and, to a great extent, addresses the urban problems that existed in the specific localities prior to the regeneration process. Additionally, the findings relate to community effectiveness supporting the advantages of the creative sector in promoting the authenticity of a place, inclusiveness, generating cultural value, and creating positive economic impacts.

However, the case of Savamala and, over time, the case of NDSM Wharf demonstrate that regeneration and its positive outcomes are not solitary endeavors but collective efforts at the structural level. Urban regeneration requires structural, institutional, and cultural underpinnings in terms of shared mental models, as well as support from public institutions and regulations. Brokerage, financial support, accountability, involvement and collaboration among actors, and the monitoring of the regeneration process are also essential for long-term success.

It is noteworthy that urban regeneration is susceptible to path and context dependency, which is evident in both cases. These dependencies affect the urban regeneration of the riverfronts differently. Discrepancies in urban governance can be attributed to the structural underpinnings, and institutional legacies that are deeply entrenched in the prevailing perceptions of how urban governance ought to operate, what is deemed legitimate, and to what extent civil society and citizens should be engaged in the decision-making.

The results of the comparative analysis suggest that network governance modes generate a greater degree of overall effectiveness. Furthermore, the positive outcomes of the regeneration process can be discerned in the urban contexts that support the development of this type of governance structure. This underscores the significance of network governance theory, particularly in the investigation of the regeneration of former industrial riverfronts. Conversely, the governance mode such as hierarchy exhibits limited overall effectiveness, while the fragmented-governed network mode exhibits overall effectiveness to a great extent, but with robust limitations. The former is not effective, as it is not inclusive and relies heavily on the interests of private actors and a handful of political elites, while the latter may lack the stability necessary to engender positive outcomes over the long term.

Conclusion

The findings of this comparative study have relevance for research on urban regeneration in similar contexts, such as in Belgrade or Amsterdam. The governance modes observed in Belgrade can support the investigation of urban regeneration in capital cities that have yet to revitalize their former industrial riverfronts and are in haste to commence this process to improve their inter-urban competitiveness and bolster their urban economies. Additionally, these modes may be relevant for cities lacking strict regulations governing urban development, where the market dictates the revitalization of riverfront areas. Furthermore, they may be applicable in cities where urban governance lacks participatory mechanisms, and the political elites wield significant influence over urban governance without seeking input from local spatial experts and citizens. Lastly, these modes may also hold relevance for cities where local government possesses limited political and economic resources to spearhead riverfront regeneration.

In contrast, the governance modes observed in Amsterdam can support research on urban regeneration in capital cities with more time to conduct thorough investigations and develop comprehensive plans for revitalizing their former industrial riverfronts, and for improving their position in inter-urban competition and enhancing their urban economies. Additionally, these modes may be relevant for cities with stringent regulations governing urban development. Furthermore, they may be applicable in cities where urban governance includes participatory mechanisms, and political elites have significant influence over urban governance while seeking input from local spatial experts and citizens. These modes may also hold relevance for cities where local government possesses the political and economic resources necessary to drive riverfront regeneration.

Finally, the research findings possess limited applicability in cities that develop within distinct socio-economic, political, and institutional contexts than those selected as the case studies. Further investigation is recommended to explore governance modes for regeneration programs in cities located outside the context of Belgrade and Amsterdam.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because only certain groups (e.g., researchers, students) may access the dataset. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to draganakostica1987@gmail.com.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because all participants were informed of the study’s purpose, methods, and their right to withdraw at any time. Consent was obtained, and data was anonymized to ensure confidentiality. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their oral informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. HafenCity University Hamburg financially supported the research for 2 years.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a condensed version of my doctoral dissertation, Urban Transformations of Former Industrial Neighborhoods: Scrutinizing Urban Networks – A Comparison of Savamala (Belgrade) and NDSM Wharf (Amsterdam), published by HafenCity University Hamburg in 2024 (https://doi.org/10.34712/142.47). I am deeply grateful to HafenCity University Hamburg for supporting 2 years of research through a scholarship. I extend my heartfelt thanks to Professor Dr. Gernot Grabher for his invaluable supervision and for introducing me to social network theory and its application in urban studies. I would also like to acknowledge the significant contributions of Patrick Kenis and the late Keith G. Provan to the development of network governance theory and empirical research, which greatly informed and inspired my own work. The title of this paper pays homage to the seminal article Do Networks Really Work? by Keith G. Provan and H. Brinton Milward (1999).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

References

1

Beach D. Pedersen R. (2013). Process-tracing methods: foundations and guidelines. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

2

Bevir M. (2013). A theory of governance. London: University of California Press.

3

Bevir M. (2020). Governance, a genealogy [lecture]. London: King’s College. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q62H7Q_dsUo.

4

Bjorna H. Aarsæther N. (2010). Networking for development in the north: power, trust, and local democracy. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy28 (2), 304–317. 10.1068/c0942

5

Blanco I. Lowndes V. Pratchett L. (2011). Policy networks and governance networks: towards greater conceptual clarity. Polit. Stud. Rev.9 (3), 297–308. 10.1111/j.1478-9302.2011.00239.x

6

Bryman A. (2012). Social research methods. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

7

Burt R. S. (1992). Structural holes: the social structure of competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

8

Charmaz K. (2000). “Grounded theory: objectivist and constructivist methods,” in Handbook of qualitative research. Editors DenzinN. K.LincolnY. S.2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 509–535.

9

De Klerk E. (2017). Make your city: the city as a shell. Netherlands: Trancity.

10

DiMaggio P. (1997). Culture and cognition. Annu. Rev. Sociol.23 (1), 263–287. 10.1146/annurev.soc.23.1.263

11

Dominguez S. Hollstein B. (2014). “Mixed methods social networks research: an introduction,” in Mixed methods social networks research. Design and applications (New York: Cambridge University Press), 3–35.

12

Emirbayer M. Goodwin J. (1994). Network analysis, culture, and the problem of agency. Am. J. Sociol.99 (6), 1411–1454. 10.1086/230450

13

Emirbayer M. Goodwin J. (1996). Symbols, positions, objects: toward a new theory of revolutions and collective action. Hist. Theory35 (3), 358–374. 10.2307/2505454

14

Evans G. (2003). Hard branding the cultural city: from Prado to Prada. Int. J. Urban Regional Res.27 (2), 417–440. 10.1111/1468-2427.00455

15

Evans G. (2005). Measure for measure: evaluating the evidence of culture's contribution to regeneration. Urban Stud.42 (5/6), 959–983. 10.1080/00420980500107102

16

Ferguson J. E. Groenewegen P. Moser C. Borgatti S. P. Mohr J. W. (2017). “Structure, content and meaning of organizational networks,” in Network research in the social sciences. Editors BorgattiS. P.MehraA. (Springer), 1–15.

17

Florida R. (2005). The flight of the creative class. New York: Harper Collins.

18

Fuhse J. Gondal N. (2015). Networks and meaning. Int. Encycl. Soc. and Behav. Sci.2 (16), 561–566. 10.1016/b978-0-08-097086-8.10447-7

19

Fuhse J. Mutzel S. (2011). Tackling connections, structure, and meaning in networks: quantitative and qualitative methods in sociological network research. Qual. and Quantity45 (5), 1067–1089. 10.1007/s11135-011-9492-3

20

Goffman E. (1974). Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

21

Goffman E. (1979). Form of talk. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

22

Grabher G. (2006). Trading routes, bypasses, and risky intersections: mapping the travels of `networks' between economic sociology and economic geography. Prog. Hum. Geogr.30 (2), 163–189. 10.1191/0309132506ph600oa

23

Granovetter M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol.78 (6), 1360–1380.

24

Grodach C. (2017). Urban cultural policy and creative city making. Cities68, 82–91. 10.1016/j.cities.2017.05.015

25

Grubbauer M. Čamprag N. (2019). Urban megaprojects, nation-state politics and regulatory capitalism in Central and Eastern Europe: the Belgrade Waterfront project. Urban Stud.56 (4), 649–671. 10.1177/0042098018757663

26

Harvey D. (1989). From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: the transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B, Hum. Geogr.71 (1), 3–17. 10.2307/490503

27

Healey P. (1999). Collaborative planning: shaping places in fragmented societies. London: Macmillan.

28

Healey P. (2006). Urban complexity and spatial strategies: towards a relational planning for our times. 1st Edn.London: Routledge. 10.4324/9780203099414

29

Heller K. Price R. H. Reinharz S. Riger S. Wandersman A. (1984). Psychology and community change: challenges of the future. 2nd ed. Homewood, IL: Dorsey.

30