Abstract

This paper focuses on the concept of craft entrepreneurship, focusing on the career trajectory of Pol Polloniato, an “artiere”—someone who merges artistic vision with traditional craftsmanship—and a renowned ceramist from Nove, Bassano del Grappa, Italy. Italian craft, particularly in the Veneto region, has deep cultural and economic roots intertwined with family businesses and industrial districts. An artisan entrepreneur blends traditional, handmade techniques with innovation, prioritising cultural value over the production of functional goods. Craft entrepreneurs contribute to regional development, creating social and economic value through their craftsmanship, frequently within family businesses or as independent artisans, while also engaging with their communities. Through the lens of Polloniato’s career, this study highlights how an artisan navigates the complex relationship between tradition, innovation, and community, thus becoming a craft entrepreneur. The article proposes a four-step process model for artisan entrepreneurship, rooted in career development, which includes phases of cultural rootedness, experimentation, legitimation, and return to community. This research is part of a wider Horizon Project. The findings have implications for regional development policies aimed at supporting craft ecosystems and ensuring their sustainability in the face of economic challenges.

Introduction

Artistic craftsmanship is positioned at the intersection of art and craft production (Adamson, 2007), as well as heritage protection (i.e., intangible heritage), cultural and creative industries, and cultural entrepreneurship. Italian craftsmanship is characterized by cultural ecosystems, which overlap with industrial districts' literature (Beccatini, 2017; Pyke et al., 1990; Bettiol, Micelli 2014), and by family businesses as the most diffused business organization. From this social and economic milieu emerges the figure of the artisan entrepreneur (Ratten et al., 2019). Generally, Italian artisan entrepreneurs, especially in the Veneto region, have experienced representational difficulties with Attività Economiche (ATECO) codes because they are not recognised as a special profession different from, for example, plumbers or technicians (Cacciatore and Panozzo, 2022). They are identified only by the number of employees that they have from artisan associations. This homogenising representation of the craft entrepreneurial sector hides specific entrepreneurial aspects and visions of the artisan craft maker, especially of the artistic artisan craft maker. However, studying the specificities of the artisan entrepreneur is crucial to understand how their behaviour is transforming the regions, especially regenerating post-industrial districts after the economic crisis of 2009 (Kapp, 2017).

Ratten (2023) identifies different types of entrepreneurship, among which is the artisan entrepreneur, which involves the use of handicraft abilities to produce products. Creative entrepreneurs, meanwhile, produce something outside the box that does not exist on the market, and heritage entrepreneurs seek to understand how heritage in terms of culture and history affects innovative business ventures. The small business entrepreneurs focuses on how small business owners utilize entrepreneurial thinking. However, according to the author, more research needs to be done on linking artisan entrepreneurship to other forms of entrepreneurship to understand how family and heritage influences business development (Ratten, 2023). This article shows how the artisan entrepreneur often integrates different types of entrepreneurship in their activity, since the craft maker’s products are tied to tradition and heritage but are also innovative in terms of materials, methods, or creative process and frequently are organized as small family businesses.

The artisan entrepreneur, or craft entrepreneur (Pret and Cogan, 2018), is generally defined as a creative professional whose production is based on traditional and handmade techniques but who seeks to innovate craft production in connection with the craft ecosystem in which he is situated (Ratten et al., 2019) and who values creation above profit maximisation (Solomon and Mathias, 2020). This is often labelled as a “lifestyle entrepreneur” (Ratten et al., 2019). Also, artisan entrepreneurship focuses on the production of cultural goods, which generally serve an aesthetic and expressive purpose more than a utilitarian function (Pret and Carter, 2017; Pret and Cogan, 2018) and, similar to cultural entrepreneurs in the CCI, they value business only as a means to realising their cultural and creative ideas (Werthes et al., 2018). Moreover, artisanal and DIY productions are generally tied to ethical consumption and presented as an alternative to neoliberal globalisation markets (Curtis, 2016).

Artisan entrepreneurship is usually described in relation to tourism and regional development (Hasanah et al., 2023; Hoyte, 2018; Teixeira and Ferreira, 2018). In rural areas they encourage creative tourism (Bakas et al., 2018; Marques et al., 2018), adding social and economic value (Ramachandran et al., 2012; Thomas et al., 2013 cited in Pret and Cogan, 2018). Bakas et al. (2018) identified the artisan entrepreneur as a mediator in rural areas or small cities who takes on multiple roles as a networking agent who organises creative tourism experiences, bridging the gap between artisans and tourists. The link of artisanal entrepreneurs with tourism is not only based on revitalising communities or economic or lifestyle goals but also on the cultural component of their business. As Ratten et al. (2019) point out, artisans are characterised by their “mindset of social consciousness as they pass cultural skills across generations” and by their distinctive feature of creating a “business that has a distinctive cultural component”. These characteristics make the artisan entrepreneur a “community entrepreneur” as they “depend on the regional environment for their cultural heritage” (Ratten et al., 2019). So, the connection between the community, the territory, the artisanal creation, and business is cultural heritage.

Among the most discussed topics in cultural and artisan entrepreneurship are behaviour, motivation, and personality traits (Hoyte, 2018; Werthes et al., 2018), business models, and entrepreneurial education (Dobreva, 2020). From a psychological perspective, cultural entrepreneurs have to combine economic values with creative ones, but generally they lack knowledge of business management and they need to balance artistic, financial, and self-development needs (Werthes et al., 2018). Through their autonomy and creativity, they show high tolerance for ambiguity, perseverance, and self-reliance. Pret and Cogan (2018) define one of the main characteristics of artisanal behaviour as “coopetition,” meaning the relationship between competition and collaboration among craft makers. For example, they may collaborate on product development or share a network, and this collaboration creates a competitive advantage (i.e., reducing costs, strengthening bargaining position, and allowing them to compete with big rivals). These collaborative practices, according to the authors, are governed by tacit norms among the craft community; members who take advantage of the collaborative relationship would be excluded. The motivations of the artisan entrepreneur rely on the personal satisfaction of doing a meaningful job, which is flexible and independent, and permits a more positive work-life balance. In addition, artisan entrepreneurs are also caring for the communities they are part of, generating social value with sustainable tourism and economic development of the region (Pret and Cogan, 2018). This peculiar satisfaction has led to a stream of research on “passion-driven entrepreneurs”, focusing on the entrepreneurial effort led by passion and the personal hobbies that relate to free-time activities (Pagano et al., 2021), some aspects of which can apply also to artisan entrepreneurs.

The most common business model for artisanal entrepreneurs is the family business, meaning a business owned and managed at least 15–25% by family members (Ramadani et al., 2017). Artisan entrepreneurs are usually small family businesses, whose artisanal production could be the only source of income for the family, or an additional economic activity carried on in their free time (i.e., hobbyists). The continuity of the business across generations is also at the core of family businesses, however, in artisanal entrepreneurship in Italy, this is currently at stake due to the low attractivity of artisanal activity in terms of profit. Countering this trend, there is a new wave of young craft makers (i.e., Neo-craft) who do not have family ties with the artisanal activity but start an artisanal business, usually in a rural or remote area, attracted by the independence, meaningfulness, and “coolness” of craft activities in opposition to “bullshit jobs” and alienated forms of work (Gandini and Gerosa, 2023).

The literature on craft entrepreneurs analysed so far highlights several characteristics of these figures, but most often craft entrepreneurs are described in medias res, showing how they play their role in a specific community but not how they got there. We do not know much about how the craft entrepreneur navigates the tensions between the artistic, artisanal, social, and entrepreneurial spheres or how one becomes a craft entrepreneur. Consequently, we do not know much about how the career trajectory affects the role of craft entrepreneurs and their legitimation, which permits them to contribute within a local context, where partnerships with other artisans and stakeholders are particularly relevant. This is what we aim to do in this article, where we analyse the career trajectory of Pol Polloniato, an artist-craft maker who defines himself as an “artiere,” which, according to critics, is someone who thinks like an artist but acts like a craft-maker. This new definition also highlights the identity-related issue of craft entrepreneurs, i.e., how they envision their role and activity inside the community of artisans and how this differs from the traditional entrepreneur one. Without a better understanding of craft entrepreneurs and their entrepreneurial identity, it is difficult to understand their career and to ensure them the support of policymakers.

Pol Polloniato is particularly relevant to Nove, a small town near Bassano del Grappa in Italy, with immense historical importance as a ceramics district. Analysing the characteristics of the artisan entrepreneur in Nove through the analysis of Pol’s career allows us to shed light on how one becomes a craft entrepreneur and how one builds a role through his career path. We pay critical attention to education, the entrepreneurial dimensions of the artisan entrepreneur, and his connection with the craft community.

The contributions of the article reside in (1) the focus on the craft-entrepreneur not as an abstract category per se but in relation to a specific territory within a ceramic district (Nove) and not as a single entrepreneur but in relation to the community of craft-makers and secondly, (2) the delineation of a process model of the artisan-artist entrepreneur based on four main steps. The process model, based on the analysis of a single career, aims to provide a thorough description of how a craft-maker can become an artist–entrepreneur, highlighting all the ambiguities and nuances underlying this trajectory. The process model can serve as a guide for replicating the study in other contexts within the artistic craft sector or in territories and districts with a traditional craft legacy.

In the following section, the ceramic ecosystem of Nove is briefly introduced, followed by the methodology used in the research. The findings section analyses Pol’s career, while the discussion section theorises a four-step artisan entrepreneurial process model, which highlights the fundamental characteristics of the artisan entrepreneur. The conclusion summarises the main findings and opens up avenues for future research and policy implications.

The ceramic ecosystem of Nove

Nove is part of a phenomenon that characterised some regions of Italy in the 70s and 80s, particularly Emilia, Tuscany, and Veneto, where the concentration of specialised firms gave rise to industrial districts (Marshall, 1890 in Beccatini, 2017). These districts act as socio-economic entities that consist of firms in a specific sector concentrated in a specific region that exhibit cooperative and competitive behaviours. Nove is an industrial district that has specialised in pottery production for three centuries, which is why it is also known as “the city of ceramics.” In particular, it has two main production lines: artistic pottery and porcelain and artistic glass production.

In addition to the proximity to the Brenta river, which was fundamental for the functioning of the kilns and the retrieval of raw materials, the local production of ceramics was incentivised in the XVIII century by the Republic of Venice. In 1732, it bestowed a 20-year economic privilege to Giovan Battista Antonibon for the production of ceramics in Nove. Thanks to this concession, Antonibon started a successful artisanal business (later acquired by Barettoni) based on the production of ceramics, majolica, and later of porcelain, which lasted decades and flourished, expanding to new markets in Italy in the Veneto region but also abroad to Germany, Austria, and Turkey. In the second half of the XIV century, new pottery manufacturing companies opened in Nove. The use of “terraglia” started to characterise this district’s production for its more economic cost together with more traditional porcelain production. After the two World Wars, in the 50s, the production of ceramics in Nove followed the Italian economic boom with a rapid growth and reached international markets not only in Europe (Germany) but also overseas (US). To give an idea of the importance of ceramics in Nove, in a town of around 5,000 inhabitants, after the Second World War, there were around 4,600 people in Nove with a job in ceramics and around 160 companies, including one-man businesses and larger enterprises (from an interview with Giancarlo Caron, ceramist and former municipal councillor in Nove). The economic crisis of 2007–2008 strongly impacted the industrial district of Nove, which saw the closing of many historical ceramics firms, complementary to the decreasing number of new artisans (generational gap). Nowadays, pottery production is mainly centred around furnishing accessories and everyday objects such as dinnerware and tableware. Some small artisan studios have survived with their artistic production, without reaching, however, the volume of production of the past decades and sometimes struggling to sustain their activity.

Artisan entrepreneurs are trying to innovate ceramic production and the Nove district through initiatives and institutions, such as the Museum of Ceramics (inaugurated in 1995), the local school (Istituto d’Arte per la Ceramica later Liceo Artistico), and the Festa della Ceramica/Portoni Aperti, a show and market dedicated to pottery production with hundreds of exhibitors coming from around the world (Rausse, 2019; Rausse and Rognoli, 2023). Nowadays, the ceramic sector still plays a significant role in Nove’s economy and in the Veneto region. According to a recent report, Confartigianato Vicenza Quintavalle and Carlotta Andracco (2024), at the end of June 2024, the ceramics sector—which produces mainly artistic and traditional ceramics, tableware, other household goods, and ornamental ceramic articles—had 2,974 enterprises, among which 2,222 were craft enterprises, accounting for almost three-quarters (74.7%) of the sector. Ceramic companies generate a turnover of €450 million, of which 62.4% is exported (a 16.0 percentage point higher share than the 46.5% for manufacturing), and an added value of €182 million. Micro and small enterprises generate 82.9% of employment, 59.9% of added value, and 54.3% of turnover in the sector. In terms of employment, the ceramics sector employs 6,123 people, of whom 3,697 are in the craft sector, accounting for 60.4% of the sector’s employees. In 2023, micro and small enterprises required 860 workers in occupations related to ceramic production, of which 540, or 62.8%, were hard-to-find, a share that is 14.7 points higher than the 48.1% of the total number of people employed in micro and small enterprises.

In Veneto, there are 207 ceramic companies, employing 674 craft employees. After Sicily, Campania, and Toscana, Veneto is the fourth region for highest number of craft companies (207) among the total number of companies (272), and the sixth most popular region for specialized ceramic production. In particular, Vicenza province, which includes Nove and Bassano del Grappa, is the second most popular province of Italy for specialized ceramic production.

Veneto is also the leading region for exports of ceramic products, accounting for 1.13% of regional added value and accounting for almost a quarter (23.8%) of Italian exports in the sector. The most recent figures for the first quarter of 2024 show a growth in exports of ceramic products in Veneto of +16.5% compared to the same period in 2023, more than three times the +4.9% recorded nationally. Of the main destination markets, the greatest growth was seen in Denmark (+114.5%), the United Kingdom (95.8%), and the Czech Republic (+54.5%).

Methodology

The article is part of a broader Horizon Research project, Hephaestus (Grant agreement ID: 101095123), which focuses on four European craft ecosystems (Bassano del Grappa in Italy, Venice in Italy, Bornholm in Denmark, and Dals Långed/Fengerfors in Sweden). While the whole project focuses on craft-makers’ business models, relationship with technology, controversies, lifelong learning, and career paths, in this paper we focus only on the ecosystem of Nove, were we conducted 27 interviews lasting from 30 min to 180 min in the second half of 2023 and the first half of 2024. The most important empirical material for this paper comes from a semi-structured interview with Pol Polloniato that was conducted in July 2023 in Nove, lasted 2 h, and was recorded and transcribed by the authors, and by informal discussions with Pol during public events connected to the project. Nonetheless, our sensemaking of Nove relies also on the other interviews carried out during the project and to reconstruct the career of Pol Polloniato we relied also on other information available online.

From a methodological perspective, we proceeded as follows: i) we selected the ecosystem of Bassano del Grappa/Nove due to its artisanal tradition in ceramics but also in other crafts such as textiles and paper; ii) we identified a series of actors to interview based on their historical and practical experience with craftsmanship within the ecosystem—these included artisans, local administrators, technical school teachers, entrepreneurs, and representatives of craft networks; iii) we began by interviewing some key actors and then added others through snowball sampling. It is worth noting here that the community of Nove is small, so many interviewees knew each other, and when one person suggested someone to interview, that same recommendation often emerged from other interviews as well; iv) although we did not reach theoretical saturation for many of the research questions guiding the broader project, the figure of Pol Polloniato quickly emerged as central within the community, which led us to focus this specific study on him; and v) we then decided to collect all available online information about Pol Polloniato, both to triangulate what he had shared with us and to assess his recognition through discipline-specific indicators such as awards and exhibitions. The other interviews, therefore, are not all directly focused on Polloniato himself but rather on the Nove ecosystem, within which his figure frequently emerges.

The decision to focus solely on the case of Pol Polloniato, albeit contextualized within the empirical setting of Nove, is driven by a methodological rationale aimed at problematization (Alvesson and Sandberg, 2011) through an exemplary case in order to generate insights by “identifying and challenging assumptions that underlie existing theories and, based on that, constructing novel research questions” (Alvesson and Sandberg, 2011: 253). For us, problematization is understood as an “endeavour to know how and to what extent it might be possible to think differently, instead of what is already known” (Foucault, 1985: 9).

We therefore aim to exploit the full capacity of qualitative research to produce thorough descriptions capable of providing a detailed account of concrete settings (Cornelissen, 2017) and of conveying the richness and particularities of a case (Tsoukas, 2009). In this way, by zooming in on an exemplary case—either because of its empirical depth or for the practical implications it may entail—it becomes possible to translate a rich narrative that brings to light nuances and ambiguities into a process model, which represents a set of analytically structured observations (Langley et al., 2013: 8). This, of course, comes at the expense of generalization and comparison across cases. And not because one theoretical approach is better than the other: both offer different styles of explanation and theoretical contribution (Wright, 2015). It is simply a matter of preserving the explanatory potential of qualitative research (Cornelissen, 2017), avoiding attempts at generalization which—based on only a few cases—would not be epistemologically sustainable and would, in fact, result in the trivialization of qualitative research, solely for the sake of mimicking quantitative approaches (Van Maanen, 1995).

In essence, then, we position ourselves within the tradition of process research (Tsoukas, 2009), and our goal is to rationalize our empirical case into a process model that does not aspire to be generalisable but rather seeks to highlight the nuances of the artist–entrepreneur’s role through a thorough description.

From an analytical perspective, we used NVivo to analyse the interviews, applying thematic coding (Saldaña, 2021). The online information was analysed to fill in the gaps in Pol’s narrative and to provide a reality check against his own account, as well as to ground the analysis of his success not only in his personal story but also in verifiable achievements within the art world. Both authors conducted the coding independently and then discussed the results in order to arrive at a shared sensemaking.

Findings: Pol Polloniato as the artisan entrepreneur

In this section, we reconstruct the personal story of Pol Polloniato, focusing on the aspects relevant to his journey toward becoming an artist–entrepreneur. The information gathered through interviews and interactions with him is compared with publicly available sources concerning his artistic and professional trajectory (Biolchini, 2020; Cologni, 2024; Tich, 2018), as well as the recognition he has received in terms of legitimacy (see Table 1 and the relative footnote). The categorization into different periods, however, is the result of our own interpretive work.

TABLE 1

| Solo exhibitions | |

|---|---|

| 2008 | “Capricci Contemporanei” at the historic Antonibon Manufacture in Nove (VI), his first solo exhibition |

| 2012 | “La Métamorphose de la Tradition” at Galerie Ock’omsa in Vallauris, France, a project that represented the evolution of his artistic language, blending tradition and innovation |

| 2016 | “METAFORME” MACC Museum of Contemporary Ceramic Art in Torgiano (PG) |

| 2019 | “Off Road” at the Civic Museum of Bassano del Grappa (VI). This exhibition marked an important moment of reflection on his journey, where he engaged in a dialogue with the historical traditions of the Vicenza region |

| 2021 | “Metamorfosi FORME NEL VERDE” at Palazzo Chigi | San Quirico d'Orcia, Siena |

| 2022 | “Il bianco senza tempo” at the Civic Museums of Bassano del Grappa, curated by Elena Forin. This exhibition, celebrating over 15 years of dedication to ceramics, represented a retrospective of his most significant works |

| Group Exhibitions | |

| 2009 | Participation in the 56th Faenza Prize, one of the most important international competitions dedicated to ceramics |

| 2012 | European Applied Arts Prize | Mons Belgium. 22nd International Biennale of Art Ceramics | Vallauris, France. 12th Biennale of Ceramics in Andenne, Belgium. Tendances - Galerie de L'ô. Brussels (Belgium). Pompeo Pianezzola and Paolo Polloniato - Civic Museum of Ceramics in Nove (VI) |

| 2013 | “Paradise Now” Extra Spazio Gallery | Rome. 58th Faenza Prize | MIC Faenza. Paolo Polloniato & Noemi Niederhauser - Puls Gallery Brussels (Belgium) |

| 2014 | Design Art Basel 2014 - Antonella Villanova Gallery Florence | Miami. European Ceramic Contest 2014 | Bornholm, Denmark. Ceramic Event 6 Galerie de L'ô | Brussels, Belgium. 23rd International Biennale of Art Ceramics | Vallauris, France. Design Art Basel 2014 Antonella Villanova Gallery Florence | Basel. Open To Art Officine Saffi Gallery | Milan |

| 2015 | 59th Faenza Prize | MIC Faenza. Miart 2015 Milan City Fair - Antonella Villanova Gallery Florence |

| 2016 | “Terra! Una storia nomade” Museum of Ceramics in Mondovì (CN) |

| 2017 | “Keramos: tukaj in zdaj” - City Gallery, Piran (Slovenia). Eunique - Karlsruhe (Germany). “In The Earth Time.” Gyeonggi Ceramic Biennale Yeoju Dojasesang (World Ceramic Livingware Gallery) Gyeonggi, Korea. Collect Saatchi Gallery | LondonUK. |

| 2018 | “Ceramics Now” special edition of the 60th Faenza Prize | MIC Faenza. XXV Mediterranean Ceramics Competition - Museum of Ceramics in Grottaglie (TA) |

| 2019 | Terre d’Italia - XXV International Biennale of Art Ceramics | Vallauris, France. Alchemysts Cambi Auction House | Milan. “Il colore interiore” - Spazio FACTO, Montelupo Fiorentino. “All that glitters is not gold” - 2019 Sands Ceramic Exhibition. Macau (China) |

| 2020 | Italy. Una Generazione Premio Palombini - Church of San Pacrazio, Tarquinia |

| 2022 | International Ceramic Art Biennale Jingdezhen. Ceramic Art Avenue Museum | China |

List of exhibitions.

Data for this table were also collected online from the following websites: https://www.celesteprize.com/_files/cstudios/curr_28655.pdf, http://www.gmazzotti1903.it/pol-polloniato.html, https://first-drops.it/artists/paolo-polloniato/, https://pol9york.blogspot.com/. Data were retrieved on 11/09/2024.

Paolo “Pol” Polloniato is now a well-known artist and craft-maker in Nove, where he is a central point of reference for the ecosystem of pottery production. Pol is an artisan entrepreneur since he uses his skills and hands to create cultural goods and processes and new markets (Ratten and Usmanij, 2021), and he does so developing products which are not primarily aimed at functional use (Pret and Cogan, 2018). He is particularly relevant as an entrepreneur since, given his path and legitimation (as we will try to show), his vision about the future of craft and pottery in an industrial district and craft ecosystem in Veneto region is particularly interesting both from a research point of view and because he is recognized as a legitimate speaker (Bourdieu, 1991) within the ecosystem of Nove.

Paolo was born and raised in Nove in a traditional family of pottery craft makers, but his choices in terms of education and career led him to develop a peculiar entrepreneurial vision for the future of Nove. His persona is a hybrid between an artist and an artisan, a Nove insider (as he was born in Nove) but also an outsider (since he lived and worked abroad while gaining relevant international prizes), and for this border position his profession and his vision are an interesting object of study concerning entrepreneurship, the future of craft and pottery in an industrial district in Veneto, and the figure of the artisan entrepreneur.

To make sense of the role of Pol as a craft entrepreneur, we divided the career and professional life of Pol into four main moments: a) Childhood and informal education on tradition, b) divergent education to foster innovation, c) legitimation and accumulation of symbolic capital, and d) return to Nove and beginning of the artisan entrepreneur.

Childhood and informal education to tradition (1978–2000)

In 1979 Paolo Polloniato, known as Pol, was born in Nove; he is a descendant of a family of master artisans who had worked in the ceramic sector for two centuries (six generations), representing an excellence in the art of majolica. His father, Giulio Polloniato, was one of the most renowned masters of majolica decoration at the prestigious Antonibon, later Barettoni, Manufacture. So, from his adolescence he was absorbed in the ceramic world of Nove. Indeed, during the summer, it was common for young people in Nove to work in ceramic firms as a seasonal job. There was such a high job offer in Nove in the 80s–90s that teenagers could be offered a job just by walking down the main street of town. Indeed, the traditional education of a pottery craft maker was to learn the job in the workshop of an older craft maker or in pottery companies, as his father who was a maestro (master) did. His father’s role, in particular, was to finely decorate, according to tradition, the classical-style ceramics made by Antonibon: ceramics with classical shapes and decorated with visions of Venice. In this phase, Pol learnt traditional ceramic production and recognizes this tradition as part of his DNA:

My relationship with ceramics runs deep—it’s a bond written in my blood. I’m the last in a long line of master craftsmen, a dynasty that has been devoted to this tradition since the early 1800s1.

This first moment is particularly important for Pol because, while he chooses not to pursue a classic career in ceramics, he is almost automatically socialised into the tradition and learns about the people, businesses, and ceramics workshops in Nove, being fully integrated into the social life of the town. So, the family roots and the ceramic production intersect in his biography on the one side by nurturing his knowledge of the material and on the other side by accumulating social capital in the community of Nove craft makers. However, he initially chose to explore other creative paths, and his high school diploma is in technical studies. Nonetheless, his artistic inclination was already present and would manifest itself in subsequent years through a wide and varied artistic exploration. Indeed, contrary to his traditional family education, he did not start as an apprentice in a bottega but instead enrolled to the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice.

Divergent education (2000–2008)

After his high school diploma, Pol decided to follow his artistic calling and enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice, where he attended the Decoration course (Section B) under the guidance of Professor Gaetano Mainenti, known for his focus on the interaction between space and form. During his years at the Academy, Pol developed an interest in painting, photography, and installations, exploring various materials and techniques, including spray paint, acrylics, synthetics, and wood dyes. Ceramics is now out of the picture: a decision that permits him to learn other artistic and artisanal languages that he will then bring into the pottery world to propose innovations. Venice and the academy as a way of learning things other than ceramics were very much on Pol’s mind from the beginning: “I felt this need [to go to the Academy], which luckily led me to break away from the world of Nove. Nove has always been a vibrant, lively place, deeply tied to ceramics—but at the same time, in my view, it’s also very closed in on itself”2.

In 2007, he completed his academic journey with a thesis entitled “Atelier: Evolution of Space-Time”. This work already hinted at his tendency to blend tradition and innovation, characteristics that would become central to his artistic path. His artistic production during his academic years focused on the analysis of physical space and social context, elements that would later be decisive in his transition to ceramics.

2008 was a pivotal year, during which Pol returned to Nove, his homeland, and confronted the severe economic crisis affecting the ceramic district:

In 2008–2009, there was a massive economic and financial crisis—the district was really suffering. That sense of decline, which I had already picked up on through my former atelier, became much more tangible throughout the area. It wasn’t the first crisis Nove had gone through over the years, but it was the decisive one, the one that rewrote the landscape. We were a major European district, one of the biggest in Europe, with 160 ceramic factories within a 2-km radius—160 operations including factories, workshops, subcontractors, and so on. From 2008 onwards—those were a couple of brutal years—it all shrank down. The big factories with 200 workers stopped, production changed, the world changed, the market changed. And that’s when I realized it was time to take hold of ceramics again. And fortunately, I understood right away that I didn’t want to use it to make functional craftwork, which is so deeply embedded in the history of this land—I wanted to use it as a medium3.

Factories were closing, industrial buildings were abandoned, and the economic outlook seemed hopeless. It was in this context that Pol decided to embrace the ceramic heritage of his family and his land but in an innovative way.

I came to understand that ceramics, for me, is a concept—it’s no longer about making a vase for flowers but about using it in the best way to express my point of view. I’m moving toward ceramic sculpture, but I arrived at ceramics, so to speak, through the back door. Fortunately, though, thanks to the Academy and a more open, all-around way of thinking, I was able to approach it more freely, you know?4

He began exploring old moulds and materials abandoned by struggling factories, transforming what was discarded into new forms of art. With his first collection of ceramics, “Capricci Contemporanei,” he mixed the historical tradition of Nove’s classic ceramic forms with modern pictorial representations, replacing the classic romantic views painted on ceramics with glimpses of contemporary urban landscapes. This contrast between past and present became Pol’s distinctive stylistic feature. In this context, he had his first solo exhibition, “Capricci Contemporanei”, at the historic Antonibon Manufacture in Nove (VI), curated by Marco Maria Polloniato and Alessandro Villanova. It is not at all secondary to point out that Pol’s first exhibition, in which he breaks down the concept of classical ceramics, painting post-industrial views instead of romantic and classical ones, takes place in the Barettoni factory, probably the oldest and most institutional of Nove’s ceramists. And this could only happen because Pol is perceived as an integral part of the territory and the community.

The artistic education of Pol “liberated” the artisan from traditional pottery creations and created the artist, or the artiere, as he defines himself:

I’d say I’m an artist who, you know, kind of embraces the original meaning of the word “artist”—someone who’s fully present and deeply respectful of the idea of craftsmanship but who also takes it one step further. In the past, the great artists were, first and foremost, great craft-makers, because they worked with their hands. (…) So some critics have called me an “artiere”—a kind of crossroads between artist and craft-maker. It means I think like an artist, but I move like a craft-maker.5

So, the difference between his artistic production and the masters’ one is that the latter innovated ceramic production from a technical perspective, while he moved on a conceptual level. In an interview with Artribune6, Pol said: “I had to act as a craft-maker but think like an artist. My task was to start from the wreckage of the past” and “my approach to this material—so familiar to me—was never about functional or craft-based purposes, because right from the start I chose an artistic, conceptual direction. I decided to develop my vision with absolute respect for the history, the place, and the people, fully aware that what lay ahead wasn’t going to be easy. I wasn’t some outsider artist coming to Nove to ‘disrupt’ a ceramic tradition. I was playing on home ground”7. His embeddedness in Nove makes him an insider with an outsider gaze, thanks to his divergent artistic education. This mix of traditional heritage and external gaze allowed him to innovate ceramic production from his lateral position:

Look, I really tried in every possible way to stay away from ceramics. I’m in it so deep … and in the end, there was a kind of DNA calling I just couldn’t escape. […] My relationship with the past is the lifeblood of my work. Everything I do is rooted in understanding the past—or rather, I study it, I look at it, I try to understand the present, and then I reimagine a future. That’s how it has to be, at least for me: you need to understand where you come from, understand why things turned out the way they did—why there used to be 80 workers here, and now there aren’t anymore. You need to make sense of that, and then you need to build. Understand this place, and what it might become8.

Legitimation and accumulation of symbolic capital (2008–2013)

In 2009, Pol began to visit Paris for personal reasons. However, after a year spent between Paris and Nove, he decided to move there: “And that was a key turning point, because after graduating I started spending time in Paris—my partner was living there for work. And that opened up a whole new perspective, a really important shift, because, you know, I stepped out of the small-town bubble and found myself face to face with Paris. For a year it was back and forth, and then, in 2008—almost 2009—I decided to move there”9.

Between 2009 and 2013 Pol lived between Paris and Brussels; in Paris, Pol continued to develop his artistic research, maintaining a connection with his ceramic background but approaching the material in an innovative and conceptual way. This period led him to consolidate his vision of ceramics not only as functional art but as an expressive artistic medium. The influence of Brussels on his work was significant, as he had the opportunity to participate in various international exhibitions and artistic projects (see the List of Exhibitions in Table 1). One important moment in Belgium was his participation in the artist residency at the Pipe-Line Cultural Centre in Andenne in 2018, where he had the opportunity to work closely with other ceramic artists and exhibit his works in the “10 Ans du Ceramique” show, celebrating his connection to the world of ceramics. Pol started to collaborate with numerous art galleries, including the Antonella Villanova Gallery, which exhibited his works at major international events such as Design Art Basel Miami/Basel.

In 2012 Pol won the Valter Dal Pane Award for “New Talents” at the 58th Faenza Prize. This award confirmed his role as an innovator in contemporary ceramics. The Faenza Prize is one of the most prestigious awards for ceramic art internationally, and winning in this context brought great visibility to his work. This award helped Pol stand out not only for his technique but also for his ability to reinterpret ceramic tradition in a modern way. In 2017, he won third place at the XXXIX International Ceramics Competition in Gualdo Tadino, further recognition of his ability to reinterpret ceramic tradition in a modern way. His work, based on the manipulation of traditional moulds and the use of white as the main colour, was appreciated for its ability to transform ceramics from a functional object into a work of art. These awards strengthened the perception of Pol as an innovator in contemporary ceramics. His use of white, the manipulation of historical moulds, and the transformation of ceramics into a conceptual art form have found widespread appreciation from critics and the public. Being recognized with prestigious awards has legitimized his unconventional approach to ceramics, moving it away from its traditional function and closer to deeper artistic reflection.

To be recognised as an artist, however, Pol needed to leave Nove and Venice and start an international career living in Belgium and Paris to be legitimized by other institutional actors from the art sector, such as galleries, and from the ceramic field.

The multiple solo and group exhibitions, the prizes, and his increasing recognition by the international art world strengthened his legitimation and symbolic capital in Italy and in Nove, where he returned in 2013, settling once again in Nove, his hometown, where he resumed the work in his studio, continuing his exploration of contemporary ceramics while maintaining a strong connection to the region’s tradition:

But I stepped into a path that other major artists here in Nove had already started: the path of ceramic sculpture. Because here in Nove, we have two very important traditions: one is the economic and productive strength of large-scale manufacturing, mainly household ceramics; and the other is a line of artistic exploration carried forward by the great masters we’ve auto-nurtured right here in our own territory—Parini, Petucco, Pianezzola, Tasca, Bonaldi, Sartori, Lucietti. Names that are stars internationally but that, unfortunately, have always been somewhat undervalued here at home10.

This period away from Nove allowed Pol Polloniato a further step forward: prizes, exhibitions, residencies, all in prestigious contexts, far away from Nove, allowed Pol to gain symbolic capital and extend his social network far beyond the borders of Nove.

Return to Nove and realisation of artisan entrepreneurship (from 2013)

In 2013 Pol was back in Nove, with a different symbolic standing and an entrepreneurial vision for the district that he developed thanks in part to his international experiences.

His return to Nove meant a strong engagement with the community of craft makers, with whom he collaborates for his artwork production. In particular, he often works with local artisans, such as Stylnove by the Zanovello brothers, who support him in creating his works.

What really matters is that my work isn’t 100% made by Pol. I’ve always needed—and still need—the support of local craft-makers, of the know-how embedded in this territory, and that’s always been something I’ve deeply acknowledged. I bring the idea, the vision, I know what I need to create, and I do part of the work myself. But if I need to get a glaze absolutely perfect on one of my more demanding pieces, I’d need 2 years of experience to do it right—and I just don’t have the time, I’m focused on other parts. So I rely on [craft-maker], for instance—he’s still one of my main collaborators—who finishes the piece and glazes it properly, to perfection. And I make a point of saying: it’s him who does the glaze. Because it’s like an orchestra—I can’t play all the instruments myself.

That’s what really matters: the support system, you know? Abroad, and even in places like Faenza, people are expected to do everything themselves. And that inevitably limits your choices and the kind of outcomes you can aim for. I’ve always allowed myself to be supported—to work with what’s basically an orchestra. In fact, this here is my studio, yes—but really, my studio is Nove11.

I love knowing that many hands have been in dialogue with mine to bring one of my sculptures to life. It’s part of what gives meaning to my work—a kind of work that is born from, and speaks about, a territory and a community that has been working this earth for over four centuries. Without the extraordinary support of the craft-makers here in Nove, I simply couldn’t achieve certain results.12

The collaboration with other craftsmen is here intended as a collaboration with a unique territory, which cannot be replicated. As Pol said, the know-how of Nove is so extraordinary that other artisans from other ceramic districts come to produce their pieces:

So that’s another key point: our know-how is extraordinary. […] And it goes beyond ceramics—within a 20-km radius, I can produce anything here. If I decide to build a spaceship, I can build it right here, seriously. From the mechanical district to furniture, glass, steel—any kind of material. This is an incredible strength that sets our territory apart on a European level—if not global, at least definitely European13.

The recognition of the role of craft makers is also very relevant to Pol, who thinks that artisans should get more credit for their work, even if they do it as third-party. Given his insider status, he can develop work relationships based on trust. So, his relationship with the ecosystem is double: on a symbolic and artistic level with the reuse of traditional techniques or forms in his sculptures, and on an organizational level, in collaboration with local craftsmen for the production of his pieces.

He envisions an entrepreneurial change for the Nove district: from an industrial standardized production of ceramic tableware and porcelain to a highly specialized ceramic district that serves a niche market. According to him, the production of traditional tableware is not viable anymore; firms need to innovate and specialize their artistic production for high-end products, and they need to “become manufacturers, the one with a capital M”. He takes Faenza as a virtuous example of this, with its micro artisanal realities with a lot of artistic craftsmen with their studio, working also as third-party. To produce less but better at an excellent level is the future of ceramic districts.

In order to achieve that, some entrepreneurial changes must occur: a new recognition of the profession of the craft maker and the creation of schools/seminars/residences to attract an international audience of craft makers and masters.

Essentially, according to Pol, what Nove lacks is not expertise but rather a strategic vision:

I’ve already seen the path—we can look at what’s happening in Faenza, for example., […] They’ve been smart in attracting people from outside, international folks. I have a lot of friends who went there to study, and then they stayed—because, well, life’s good in Romagna. […] But everyone has their own studio, their own setup, and some work a bit as subcontractors. That’s the way forward. […] I know people who say, “But the container of cups will come back.” We will no longer make a container in 1 day, but we’ll make one a month with incredible value inside14. That’s the shift we need to understand. And some people, they’ve got it15.

On the recognition of the figure of the artisan and its working conditions, Pol acts as a local memory of how craft makers used to be:

If you look at old photos of Barettoni, the decorators were in suits and ties—they looked like lords, with big moustaches and all. Even the façade of the factory was spectacular. Now it’s all turned into these horrible shacks. (…) Back then, there was also a kind of managerial culture—entrepreneurs who wanted a beautiful factory and made sure their workers had decent conditions. We have incredible examples of social welfare in Italy’s industrial past. Today, it’s more like: “just work and shut up.” I work with the younger generations—it’s not that they don’t want to work. It’s that they want to work differently. And they’re right.16

The entrepreneurial attitude in the artisanal sector should change and artisans should be valued more, in part to become attractive for younger craft makers. He adds “we must bring these guys, these craftsmen back to be truly proud to work like those who work for Ducati or Ferrari.” So, social and professional dignity should be recognised by the entrepreneur to craft makers, in opposition to Veneto’s mentality of “work and shut up.” The provincial mentality of Nove led, in the years, to cannibalisation among ceramic firms where artisan entrepreneurs competed with each other trying to produce everything at the lowest price. This insane competition and work attitude needs to change, turning toward collaboration and specialization, with a renewed status of the craft maker.

On the creation of ceramic schools or symposia, a successful example that Pol cites is Capodimonte, where a few years ago the dean of the school of porcelain relaunched the craft course; the school now has many classes.

In fact, Nove already had a very important ceramics school in the past (Scuola d’Arte), founded in 1875 by De Fabris and dedicated to the education and formation of new artisans:

One very important part of Nove’s history is the school—the Nove Art School, founded and directed by De Fabris in 1885. This sculptor, before dying, left behind an inheritance and said: “I want a ceramics school to be created in Nove.” And that’s something extraordinary. He basically founded a school to train craft-makers and workers for the future of Nove—for the district of Nove.17

The school went through different phases, but the peak was in the 1950s and ’60s, when Nove became a kind of Bauhaus […] thanks to Pianezzola. When he became principal, he launched the world ceramics symposia, which made Nove the epicentre [of European ceramics] for three editions—around ’68, ’70, and ’72. Back in the 60s and 70s, we were truly a model at the European level […] because the school moved in that direction, and the companies—the district—enabled constant access to new materials and technologies. They needed to innovate to meet the demands of large-scale production, which meant research, techniques, materials, and well-structured enterprises. So these masters were teaching on one hand and doing research on the other

The school in 2011 changed juridical form and became a Liceo Artistico, which is a high school more oriented towards theory than practice, and also lost its specialisation course in ceramics. His idea of organising new ceramics symposia, residences, or a campus for international students and artists in Nove has the aim of attracting people from outside Nove and abroad, re-nurturing a territory that has lost his vision with external stimuli and experimentation. It also resembles international schools of porcelain and ceramics in France (like Sèvres) and Belgium where this is already happening. The collaboration between schools and craft makers is also essential: in Nove, the presence of medium-sized ceramic companies played an important role in relation to the Art School: the great masters that studied at the school had the opportunity to collaborate and work in these ceramic firms. This collaboration brought the masters in contact with the firms and their technologies, producing special designer lines and artistic creations that would have not been possible elsewhere. This kind of collaboration between the school and the ceramic companies is another strength that Nove should rediscover.

Finally, another aspect that highlights Pol’s role within Nove’s ecosystem is his maieutic role and his ability to see before others how ceramics can be used for purposes beyond the production of low-cost tableware. He was among the first, for example, to explore the use of ceramics in art therapy, a practice he continues with the students he works with as a support teacher. This work, on the one hand, allows him to expand the scope of ceramics and, on the other hand, it enables him to pursue artistic research in non-trivial areas. Pol is thus able to navigate a context where he is known and recognised, with an entrepreneurial vision for craftsmanship in Nove. He can do this with credibility because he knows how to navigate the rules of the craft community in which he grew up: he is not an outsider coming to Nove to teach how things should be done. At the same time, the fact that he has not always remained in Nove gives him the legitimacy that he has been able to build only from a distance.

Discussion

From the analysis of Pol Polloniato’s career, it emerges that he is a peculiar and blurred figure, an artist but also an artisan entrepreneur. It has been argued that Swedberg’s (2006, p. 260) perspective, which defines cultural entrepreneurship as “the carrying out of a novel combination that results in something new and appreciated in the cultural sphere”, is most applicable to artisan entrepreneurship research (Pret and Cogan, 2018). This “making culture” approach originates in Dimaggio (1982) work, which focuses on the production and distribution of cultural products. Cultural products, in turn, are defined as goods “directed at a public of consumers, for whom they generally serve an aesthetic or expressive, rather than a clearly utilitarian function” (Hirsch, 1972, pp. 641–642). Ratten et al. (2019) defined artisan entrepreneurship “as an activity that involves the discovery or creation, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities based on traditional or non-mechanized processes to introduce new products (goods and services)” and the artisan entrepreneurs as skilled people working with their hands that “discover or create, evaluate and exploit opportunities for new goods, materials, processes, ways of organizing and markets.” As shown in the Findings, Pol falls into these categories as well, especially his way of producing new cultural products innovatively using tradition and his way of collaborating with the community of craft makers, creating working networks and respecting the norms of the craft community. So, even if, and perhaps even because, he is not a typical artisan, Pol offers new insights into the relevant characteristics and career paths of the artisan entrepreneur.

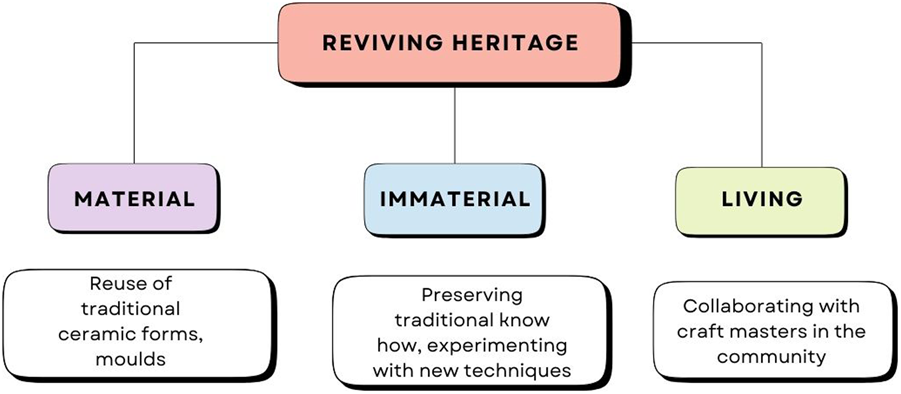

Pol Polloniato, even if coming from a traditional artisanal family, managed to differentiate his positioning and artistic-artisanal production, while at the same time reviving Nove’s ceramics heritage and traditional ceramic production. Reviving heritage in Pol’s practice is delineated in different levels (Figure 1): a) the artistic level from a stylistic-formalistic point of view; b) the immaterial heritage level of maintaining craft traditional work techniques; and c) the community level. On an artistic level, Pol’s ceramic production reinterprets, reuses, and reinvents traditional ceramic forms, moulds, and objects into new art objects that can form dialogue with contemporary art languages (e.g., Capricci Contemporanei, Pieniarendere). Even if stylistic analysis of art pieces is not at the centre of this article, it is important to acknowledge it as a symbolic element contributing to the reviving of ceramic material heritage. On an immaterial level, his experimentation in artistic production led him to push ceramic manufacturing to follow his artistic intuitions, while at the same time to better understand and learn traditional techniques from masters. Indeed, scholars, investigating the working collaborations of artists and artisans in the production of contemporary artworks, point out the mutual contribution in terms of creativity, know-how, and experimentation that originates from it (Leonardi, 2024). On a community level, his continuous collaboration with the community of craft makers for his productions is also a way of preserving living heritage. In this sense, he can also be defined as a community entrepreneur.

FIGURE 1

Reviving heritage dimensions.

A community entrepreneur, in this case, is not a mediator or an external entrepreneur who exploits local craft makers to profit from a market need or for touristic reasons but an artisan entrepreneur whose production and activity is deeply rooted in the community through working collaborations, relationships based on trust, and a cultural discourse. The entrepreneurial vision of Pol is part of a communal cultural discourse that needs to be shared among other craft makers for the ceramic district to survive and revitalise. The cultural discourse revolves around a few key points: the transmission of craft knowledge, the revitalisation of the figure of the craft maker, and the specialisation of ceramic production toward excellence. These key points can be achieved in different ways like, for instance, the invitation of external masters in the district, the opening of an international ceramic school, the organisation of an artistic residency in collaboration with local craft makers, and paying higher salaries to craft makers. So, from an entrepreneurial perspective, reviving heritage means recognising the importance of this cultural and communal perspective before individual profit maximisation.

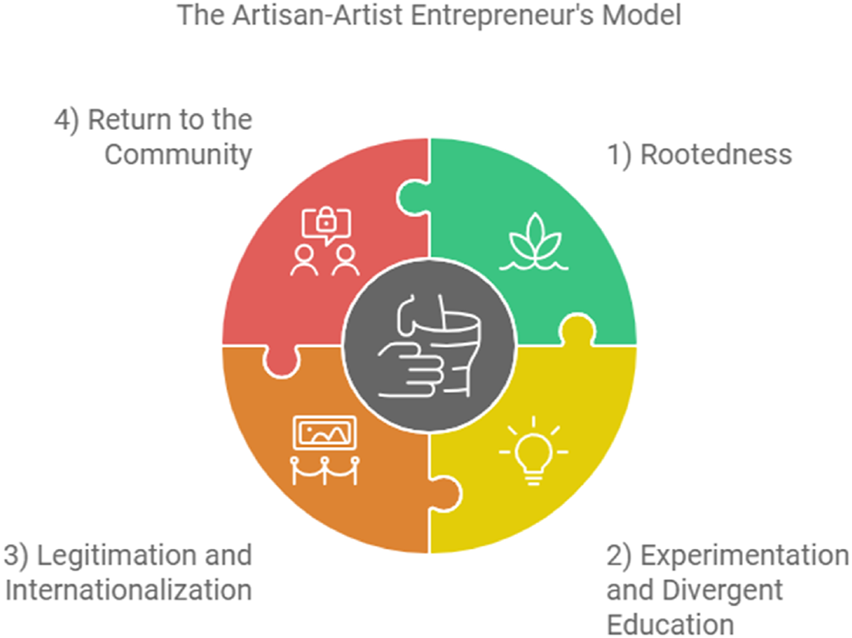

Building on the narrative developed in the findings, we constructed a process model of the artist–entrepreneur (Langley et al., 2013; Tsoukas, 2009). This represents a structured analytical account derived from qualitative data, capturing sequences of events and meaningful patterns. Unlike generalisable models, which seek abstract and broadly applicable explanations, process models emphasize the unfolding of events and contextual specificities within a single case, prioritizing depth, complexity, and theoretical insight over replication. The first step of this process model (Figure 2) is rootedness, which refers to the embeddedness of the entrepreneur in the craft ecosystem, which creates a relationship of trust with the other craft makers. In addition, this communal trust allows the entrepreneur to reinterpret tradition and traditional products with the support of the craft community (e.g., accessing company archives, collaborating with historical firms, etc). Trust enables collaboration and innovation within the community, and it also creates the possibilities for external makers or professionals to be included thanks to the endorsement of the artisan entrepreneur. Being part of a craft community is also fundamental in learning and acting according to tacit craft norms that are specific to the context. The second step is experimentation, meaning the ability to step outside of traditional craft production and be able to innovate it. This step presupposes a divergent education, which builds on traditional know-how and mastery but also integrates a conceptual and artistic or design education. Learning technical craft techniques is the starting point to subvert, reinterpret, and reuse traditional production thanks to a more conceptual, theoretical, and critical education in the artistic design field. The third step is legitimation and internationalisation in ceramics and the artistic fields. Symbolic legitimation through the support and presence of international galleries at global fairs is a well-studied cultural dynamic (Velthuis and Baia Curioni, 2015; Baia Curioni, Forti, Leone in Velthuis and Baia Curioni, 2015) according to which artistic and symbolic value (Bourdieu, 1991) is created thanks to the cooperation of different actors in the art world (Becker, 1982) who play different roles. For instance, gallerists act as gatekeepers of the art system and prizes are guarantees of artistic (and consequently economic) value. The fourth step is the return to the community to innovate and change it. Change often necessitates the creation of a cultural discourse and an entrepreneurial vision to lead actors of the community to embrace it. The artisan-artist entrepreneur, thanks to the rootedness, divergent education, and international experience, can lead the change of the ecosystem in different ways, including his/her artistic production.

FIGURE 2

Artist-artisan entrepreneurial model.

Given the blurred lines between the craft and art worlds, the business similarities between craft entrepreneurs and family businesses, and the overlapping with tourism and local development, this model represents the most important characteristics of the artisan entrepreneur in the craft sector. Being an artisan entrepreneur is not just about a certain lifestyle or answering tourists’ demand for folkloristic objects; it is about a cultural vision of heritage and innovation of craft businesses and craft communities. The relationship between the entrepreneurial dimension and heritage is typical of craft production and, in the case, of Pol is mediated by his artistic production.

Conclusion

Pol Polloniato’s career path allows us to understand how a craft-maker can become a craft entrepreneur. Rootedness in the local area is needed to be credible, but individual entrepreneurship is also necessary to enable the exploration of new paths. Furthermore, skills, talent, and legitimacy are essential, as they are the only means to acquire symbolic capital, which is crucial to unfolding the true role of the craft entrepreneur within the local context and through stakeholder networks. This process model allows us to draw implications at both the research and policy levels.

Regarding research, our work complements the existing literature that describes the characteristics of the craft entrepreneur by offering a description of how a craft-maker can become an entrepreneur through their career trajectory, thus emphasising rootedness, divergent education, and the role of symbolic and cultural capital. Clearly, the epistemological approach we adopted, while allowing us to develop a thorough description of the case and uncover rich nuances that informed the construction of our process model, also represents a limitation. As with any epistemological choice, there are inherent advantages and disadvantages, and the richness of the case—focused on the perspective of a single artist–entrepreneur—comes at the expense of generalisability. We therefore believe that further analogous studies conducted in different contexts could help assess whether the specificity of Pol’s case and the setting of Nove resonates with other craft-based contexts.

The first contribution of the article regards the qualification of the role of the craft entrepreneur as that of a gatekeeper within the local community, capable of having a positive impact on the creation and value of networks.

The second contribution refers to the process model of the artisan-artist entrepreneur that identifies four steps: education, experimentation, international recognition, and commitment to the community. These steps can be supported by local policies and by craft associations and institutions. For instance, to allow experimentation and community collaboration it would be appropriate to provide craft entrepreneurs with spaces and places where networking can be facilitated: collective workshops, shared or shareable machinery, and, in general, tools and resources that can be useful to artisans and around which they can meet and collaborate. To foster legitimation and recognition, local artisan associations and institutions could expand the availability and accessibility of networking and legitimisation tools, such as artist residencies and awards, which have played a decisive role in Pol’s legitimisation. As the literature suggests (Ratten and Usmanij, 2021), entrepreneurial education needs to be implemented not only through extra-curricular courses and case studies but also and especially from a critical perspective, questioning the over-reliance on successful entrepreneurs which reinforces stereotypes and simplifies the environmental dimensions and casualties of success. Instead, more effective policies should take into account different characteristics of entrepreneurs, their contexts, and industry. Indeed, entrepreneurship education varies among industry groups (Ratten and Usmanij, 2021), requiring diverse programs to support different entrepreneurs and, in this case, craft entrepreneurs. The case of Pol is an exemplar of a particular type of craft entrepreneur who fosters the community of craft makers and revives heritage, and it needs specific educational and entrepreneurial skills that may not be generalised for other entrepreneurs or industries.

Moreover, opening a local district to the world can provide opportunities to enrich local culture with that of other artists and craft-makers, and the role of craft entrepreneurs can echo what was historically done in Nove with the symposia organised by Pianezzola and the school. These are still remembered years later as the events that put Nove’s ceramics at the centre of Europe. The role of Pol and other craft entrepreneurs is to have a vision from which the entire district can benefit. It is up to local institutions and trade associations to create the best possible conditions for them to do so.

Statements

Data availability statement

The dataset containing the underlying data of this study is available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15491023, under a CC BY 4.0 license. The dataset adheres to the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable). Zenodo is an OpenAIRE-compliant repository that ensures long-term preservation and open access.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The HEPHAESTUS project (ID 101095123) is funded by the European Union under the Horizon Europe programme. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency (REA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Figure 2, which graphically illustrates the process model described in the text, was generated with the support of a generative AI tool (Napkin AI), based on a textual description provided by the authors.

Footnotes

1.^Original quotation: “Il rapporto con la ceramica ha per me un valore profondo, un legame di sangue. Rappresento l’ultima generazione di una dinastia di maestri artigiani che dai primi dell’800 si dedica a questa tradizione.” Quotation from the interview to Pol Polloniato available here: https://www.fondazionecologni.it/it/interviste/ar/paolo-polloniato

2.^Authors’ translation. Original quotation: “Ho sentito sta necessità [andare all’Accademia] che per fortuna mi ha portato a staccarmi dalla dimensioni di Nove, perché Nove è sempre stata una dimensione molto viva, molto in fermento, legata alla ceramica ma al tempo stesso secondo me è molto chiuso su se stessa”

3.^Authors’ translation. Original quotation: “Nel 2008-2009 c’è una situazione di crisi economico finanziaria enorme: il distretto sta soffrendo tantissimo. E questo decadentismo che già io percepivo attraverso il mio ex atelier, diventa molto più presente nel territorio. Non è la prima crisi che Nove subisce negli anni, ma è quella un po’ decisiva perché riscrive un po’ il paesaggio: era un grande distretto europeo, tra i più grandi d'Europa, dove avevamo 160 fabbriche di ceramica nel raggio di 2 km. 160 attività intese come fabbrica, laboratori, terzisti, etc. Dal 2008 in poi -ci sono un paio di anni tremendi - tutto ciò si ridimensiona, le fabbriche grandi da 200 operai si fermano e cambia la produzione, cambia il mondo, cambia il mercato. E io da là capisco che era giunto il momento di tenere in mano la ceramica e per fortuna dall’inizio lo capisco subito che lo voglio utilizzare come medium, non per creare un artigianato funzionale che è intrinseco alla storia del mio territorio.”

4.^Authors’ translation. Original quotation: “capisco che per me la ceramica è concetto, non è più necessità di fare un vaso per dei fiori, ma utilizzarla il meglio per raccontare un mio punto di vista. Ecco, mi proietto verso la scultura ceramica, ma io arrivo alla ceramica, come dire dalla porta sul retro, però per fortuna, grazie all'Accademia, grazie a uno spirito più a 360°, più libero, ecco.”

5.^Authors’ translation. Original quotation: “Io direi che sono un’artista che comunque, come dire, interpreta l’origine della parola artista, che è quella di avere una massima presenza e rispetto verso il concetto dell’artigianato che viene portato però a uno step ulteriore. Nel passato i grandi artisti erano innanzitutto dei grandi artigiani, perché lavoravano con le mani. (…) quindi io per alcuni dalla critica sono stato definito un “artiere”: che è una sorta di crocevia tra artista artigiano, che quindi ragiono d’artista ma mi muovo da artigiano.”

6.^Original quotation: “Dovevo agire da artigiano ma ragionare da artista. Il mio compito era quello di partire dalle macerie del passato”. Quotation from the interview to Pol Polloniato available here: https://www.artribune.com/professioni-e-professionisti/who-is-who/2020/05/intervista-ceramica-paolo-polloniato/

7.^Original quotation: “il mio approccio con questa materia “tanto famigliare” non fu per fini artigianali e funzionali, perché decisi di prendere da subito una direzione artistico/concettuale. Scelsi di sviluppare la mia visione nell’assoluto rispetto della storia, del luogo e delle persone, cosciente che ciò che mi aspettava non sarebbe stato per niente facile. Non ero un artista sconosciuto che decideva di venire a Nove a “stravolgere” una tradizione ceramica. “Giocavo” in casa.” In Artribune 2020.

8.^Authors’ translation. Original quotation: “Guarda, io ho cercato in tutte le maniera di non farla la ceramica. Perché ci sono dentro e alla fine ho avuto una richiesta di DNA da cui io non sono scampato. […] Il rapporto col passato è la linfa del mio lavoro. Tutto il mio lavoro si basa sul capire il passato, anzi studio, guardo il passato, capisco il presente e re-immagino un futuro. Procedimento che deve essere questo secondo me: capire le tue origini, renderti conto del perché sono andate così le cose, perché qui una volta c’erano 80 operai e ora non ci sono più, devi capire e allora devi costruire, capire questo spazio che potrebbe diventare un’altra cosa.”

9.^Authors’ translation. Original quotation: “Ed è un passaggio importante perché dopo che mi diplomo inizio a frequentare Parigi perché la mia attuale compagna viveva lì per lavoro. E questo mi porta a un confronto, a un passaggio importantissimo, perché, come dire, fuoriesco dal piccolo contesto paesano e mi confronto con Parigi, che per un anno diventa andata e ritorno e poi decido nel 2008 quasi 2009 di trasferirmi su.”

10.^Authors’ translation. Original quotation: “Ecco, ho dovuto essere riconosciuto all’esterno, ovviamente. E da lì parte, decido di dedicarmi alla ricerca ceramica che è una ricerca che cambia in questi 15 anni. […] Ma mi infilo in quella strada che già altri autori importantissimi nella strada di Nove stavano facendo, che era un po’ della scultura in ceramica. Perché a Nove abbiamo due strade molto importanti: una grande importanza economico produttiva di grandi produzioni, di stoviglierie, principalmente; ma poi c'è anche la ricerca data dai grandi maestri che noi abbiamo autogenerato qui nel territorio, che sono dal Parini, Petucco, Pianezzola, Tasca, Bonaldi, Sartori, Lucietti. Nomi che nel mondo sono delle star, ma che qui purtroppo sono sempre state un po’ sottovalutati.”

11.^Authors’ translation. Original quotation: “Molto importante è che il mio lavoro non è al 100% fatto da Pol. Io ho sempre avuto e ho ancora tutt’ora bisogno del supporto degli artigiani, del know del territorio e questo è sempre stato un dettaglio molto importante, a più ho dato riconoscimento. Io ho l’idea, ho la visione, devo portare a termine quello che devo creare, faccio una parte del mio lavoro, però se devo mettere la cristallina perfetta su un capriccio per farlo perfettamente io avrei bisogno di due anni di esperienza e invece io non ho tempo e mi occupo di altro e allora mi affido a [artigiano], per esempio -che ancora tutt’ora uno dei miei grandi terzisti - che mi smalta come si deve a regola d’arte, il pezzo finito per mettergli la cristallina. E io ci tengo a farlo capire che è lui che mette la cristallina. Perché come una sorta di orchestra, non posso usare io tutti gli strumenti. (…) E questa è la cosa molto importante, la parte di supporto, ecco. Mentre all’estero, ma anche a Faenza, loro devono comunque imparare un po’ a farsi tutto. E questo ti implica comunque l’ora delle scelte e dei prodotti determinati. Io invece mi sono sempre permesso di farmi supportare, di avere una sorta di orchestra. Infatti il mio studio è qui dove sei, ma in realtà il mio studio è Nove.”

12.^Original quotation: “Mi piace sapere che più mani hanno dialogato con le mie per dar vita a una mia scultura. Fa parte del senso del mio lavoro. Un lavoro che nasce e parla di un territorio, di una comunità che da più quattro secoli lavora la terra. Senza lo straordinario supporto delle maestranze presenti a Nove, io non potrei ottenere certi risultati.” In Artribune, 2020.

13.^Authors’ translation. Original quotation: “Quindi questo è un altro punto fondamentale: il nostro know how è straordinario. […] anche oltre la ceramica, io nel raggio di 20 km posso produrre qualsiasi cosa qua. Se decido di costruire un’astronave, la faccio qui, è chiaro. Dal distretto meccanico, il mobile, il vetro, l’acciaio qualsiasi tipo di materiale. Questa è una forza incredibile che contraddistingue il nostro territorio a livello europeo, se non mondiale ma europeo, di sicuro.”

14.^This refers to the fact that some people think that the days when at least one container of cups left Nove every day will return, but Pol envisions a Nove in which no low-value products are made but instead one truck per month of high-value products will be the norm.

15.^Authors’ translation. Original quotation “io l’ho già vista la strada: un po’ come sta succedendo a Faenza […] per esempio loro sono stati bravi ad attrarre la gente da fuori, gli stranieri da fuori, ho tanti amici che sono andati là a studiare. Poi si sono fermati là perchè poi in Romagna stai bene. […] Però ognuno ha il suo studio, ognuno ha la sua realtà, poi c'è chi fa un po’ il terzista. Questa è la strada. […]Io conosco gente che dice “ma ritornerà il container di tazzine”. Non faremo più un container nel giorno, ne faremo uno al mese con un valore pazzesco dentro, cioè dobbiamo capire questo, e certi hanno capito”.

16.^Authors’ translation. Original quotation: “Se tu vedi le foto vecchie della Barettoni, i pittori erano in giacca e cravatta, erano dei Lord, con i baffoni. La facciata stessa della manifattura erano spettacolari, adesso sono capanne orribili. (.) C’era anche proprio una cultura manageriale che esisteva nel passato dell’imprenditore che voleva la bella fabbrica e mettere magari l’operaio nella giusta condizione di lavorare. Il welfare sociale, ne abbiamo esempi pazzeschi in Italia. Mentre adesso a un certo punto tutto è dovuto, “lavora e tasi”. Io ci lavoro con le nuove generazioni: non è che non abbiano voglia di lavorare, ma vogliono lavorare in maniera diversa? e hanno ragione.”

17.^Authors’ translation. Original quotation: “Un aspetto molto importante della storia di Nove è la scuola, la scuola d’arte di Nove fondata e diretta da De Fabris, nel 1885. Questo scultore prima di morire lascia un’eredità economica e dice “Io voglio che venga creata una scuola di ceramica a Nove” ed è qualcosa di straordinario. Questo, cioè lui fonda una scuola per creare maestranze e manovalanze nella storia di Nove, al distretto di Nove. La scuola ha vari passaggi, però, il punto massimo sono gli anni 50 e 60 ,dove Nove diventa una Bauhaus […], grazie a Pianezzola, quando lui diventa preside della scuola, si creano i simposi mondiali della ceramica, significa che Nove diventa l’epicentro [europeo della ceramica]per tre edizioni, 68 70 72 circa. In quegli anni tra 60-70 […] eravamo veramente un esempio a livello europeo […] perché avevamo la scuola che andava in questa direzione e le aziende-il distretto permetteva che arrivassero sempre nuovi materiali, nuove tecnologie, perché dovevano fare le grandi produzioni in un certo tipo, che implica ricerca, che implica tecniche, materiali e aziende strutturate. Quindi questi maestri da una parte insegnavano l’altra facevano ricerca”.

References

1

AdamsonG. (2007). Thinking through craft. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

2

AlvessonM.SandbergJ. (2011). Generating research questions through problematization. Acad. Manag. Rev.36 (2), 247–271. 10.5465/amr.2011.59330882

3

BakasF. E.DuxburyN.Vinagre de CastroT. (2018). Creative tourism: catalysing artisan entrepreneur networks in rural Portugal. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. and Res.25, 731–752. 10.1108/IJEBR-03-2018-0177

4

BeccatiniG. (2017). The Marshallian industrial district as a socio-economic notion. Rev. d'économie Ind.157, 13–32. 10.4000/rei.6507

5

BeckerH. S. (1982). Art worlds. University of California Press.

6

BettiolM.MicelliS. (2014). The hidden side of design: the relevance of artisanship. Des. Issues30 (30), 7–18. 10.1162/desi_a_00245

7

BiolchiniI. (2020). Gli artisti e la ceramica. Intervista a Pol Polloniato. Available online at: https://www.artribune.com/professioni-e-professionisti/who-is-who/2020/05/intervista-ceramica-paolo-polloniato/.

8

BourdieuP. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge: Polity Press.

9

CacciatoreS.PanozzoF. (2022). Strategic mapping of cultural and creative industries. The case of the Veneto region. Creative Industries J.17 (1), 28–44. 10.1080/17510694.2022.2026059

10

CologniF. (2024). “Paolo Polloniato,” in Ceramica di Nove. Available online at: https://www.fondazionecologni.it/it/interviste/ar/paolo-polloniato.

11

CornelissenJ. P. (2017). Preserving theoretical divergence in management research: why the explanatory potential of qualitative research should be harnessed rather than suppressed. J. Manag. Stud.54 (3), 368–383. 10.1111/joms.12210

12

CurtisR. B. (2016). Ethical markets in the artisan economy: portland DIY. Int. J. Consumer Stud.40 (2016), 235–241. 10.1111/ijcs.12247

13

DimaggioP. (1982). Cultural entrepreneurship in nineteenth-century Boston: the creation of an organizational base for high culture in America. Media, Culture and Society, 4 (1), 33–50. 10.1177/016344378200400104(Original work published 1982).

14