Abstract

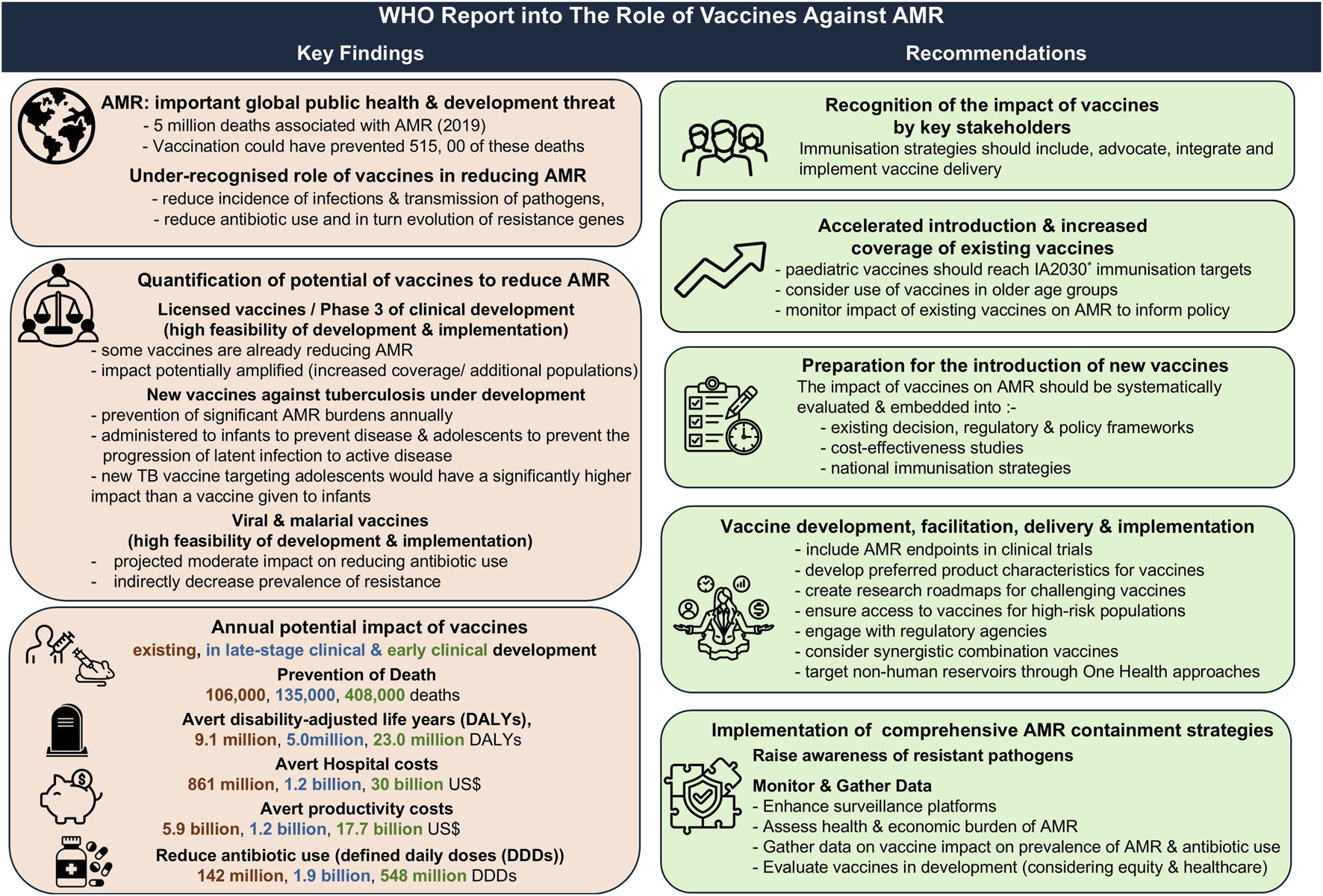

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has caused a global public health crisis, contributing to approximately five million deaths in 2019 and predicted deaths of approximately ten million annually by 2050. This equates to approximately 1.4-fold more deaths annually from AMR in 2050 than the entire COVID-19 pandemic to date. To tackle this AMR pandemic, regulatory and policy frameworks have been prepared at local, national and international levels with multi-faceted proposals and advances encompassing surveillance, diagnostics, infection prevention, antibiotic prescribing and variation of existing and novel treatment approaches. This narrative review primarily focuses on research and development which have been documented over the last five years in relation to therapeutic approaches at various stages in clinical development and the potential role that vaccines can play in the fight against AMR. This review provides an overview on antibacterial drugs, including novel classes of antibiotics, which have been recently approved, as well as combination antibiotic therapy and the potential of repurposed drugs. The potential role of novel antimicrobial, antibiofilm and quorum sensing inhibitors, such as antimicrobial peptides, nanomaterials and compounds from the extreme and natural environments, as well as ethnopharmacology including the antimicrobial effects of plants, spices, honey and venoms are explored. Novel therapeutic approaches are critically discussed in terms of their realistic clinical potential, detailing recent and ongoing trials to highlight the current interest of these approaches, including immunotherapy, bacteriophage therapy, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT), antimicrobial sonodynamic therapy (aSDT), nitric oxide therapy and microbiome manipulation including faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). The potential of predatory bacteria as living antimicrobial agents is also discussed. Importantly, there have been many technological developments which have enhanced bioprospecting and research and development of novel antimicrobials which this review draws attention to, including artificial intelligence, machine learning and Organ-on-a-Chip devices. Finally, key messages from the recent World Health Organization report into the role of vaccines against AMR provides an interesting perspective relating to prevention which can be of significance in tackling the AMR burden.

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global concern which continues to have an impact on public health both within healthcare and increasingly community settings, in relation to mortality and non-fatal health burden, as well as problems associated with treatability and additionally financial costs [1–3]. In 2016, the O’Neill report detailed that there were 8.2 million deaths attributed to cancer and predicted that in 2050, 10 million deaths would be attributed to AMR [1]. Due to this public health crisis, various global and national strategies have been devised and actioned to help tackle AMR using a multidisciplinary “One Health approach”. This framework considers the contributions to this problem attributed to human, animal and environmental factors and effective steps, which can be taken to control and limit the expansion of this problem [4].

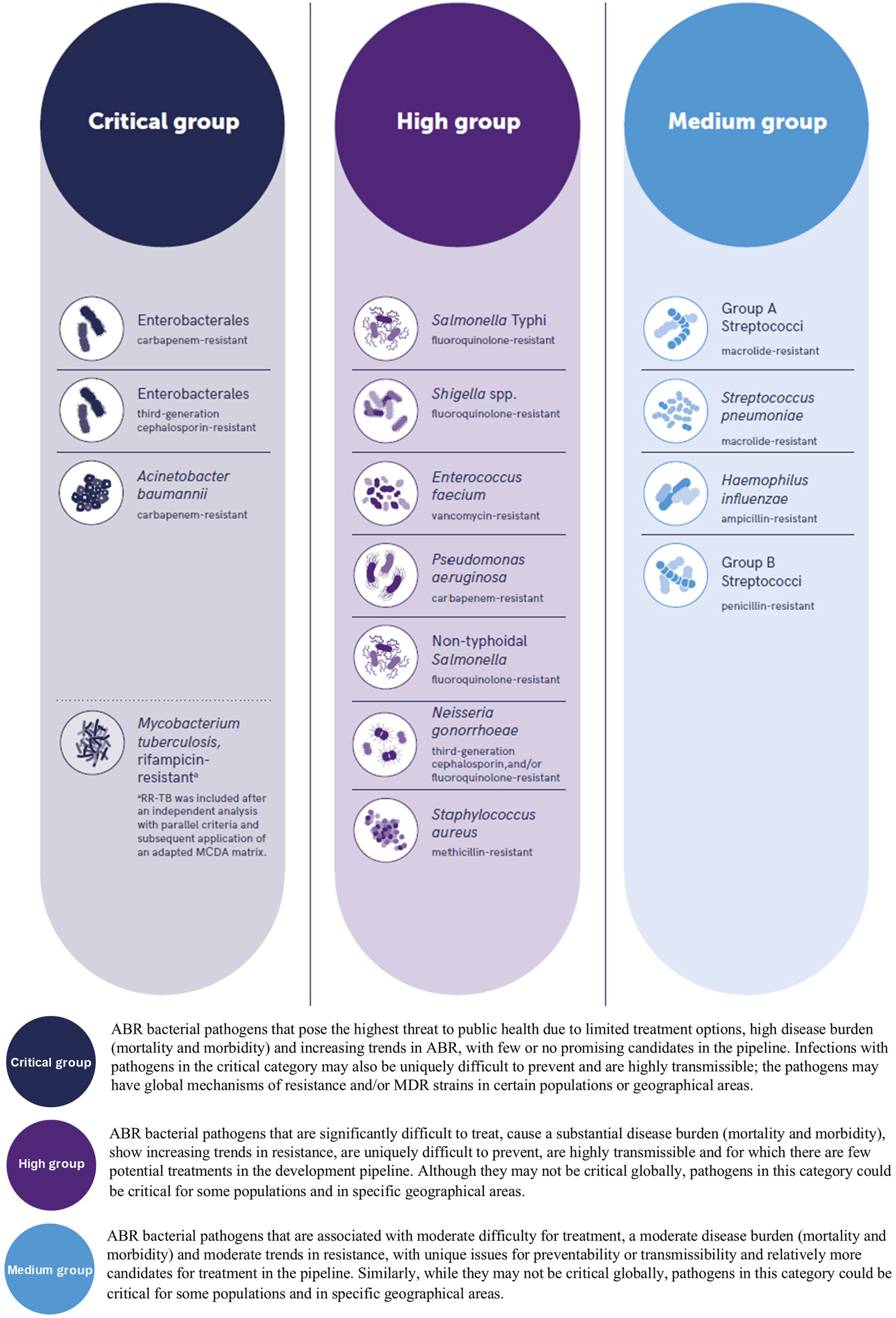

The consequences of AMR have impacted the clinical management of infections causing the World Health Organization (WHO) to update their “Bacterial Priority Pathogens List” (BPPL) in May 2024, seven years since their previous BPPL, during which time the pandemic of AMR has continued to lead to a global crisis particularly, but not limited to, low and middle income countries (LMIC), with some Gram-negative organisms now resistant to last-resort antibiotics [3]. The most recent BPPL lists one bacterial order, 11 named bacterial species and two Lancefield groupings of streptococci which are antimicrobial resistant and have been assigned to three priority groups, namely critical, high and medium, which are of global public health concern within vulnerable populations and LMIC, as well as organisms which are highly virulent, multidrug-resistant (MDR) and those with the ability to transfer resistance genes, including “transmission across the One Health spectrum”, see Figure 1 [3].

FIGURE 1

The World Health Organization (WHO) bacterial priority pathogens list, 2024. (Top) reproduced from “WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024” by World Health Organization (https://www.who.int/) licensed under, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

The recent BPPL highlights the severity of AMR as evidenced with the inclusion of organisms which are MDR. Drug resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) is a primary example of an infection which continues to cause concern, particularly as treatment regimens are dependent on the causes and complex mechanisms of resistance attributed to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex [5], with various classifications of resistance being reported such as Multidrug resistant-TB (MDR-TB), Multidrug resistant or rifampicin resistant (MDR/RR-TB) and extensively drug resistant-TB (XDR-TB) which the WHO more recently clarified in terms of definitions of Pre-XDR-TB and XDR-TB to align with treatment regimens and epidemiological reporting [6]. Another pathogen which is of global concern is Neisseria gonorrhoeae, where resistance has been increasingly reported in relation to antibiotic empirical therapy such as ceftriaxone and more recently azithromycin [7].

Although there are fifteen families of bacterial pathogens highlighted in the recent BPPL which are deemed a priority, there are groups of individuals where there is a stark reality of AMR. One such example where AMR is of major concern, is individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF), where the repeated administration and prolonged duration of antibiotic therapy, coupled with environmental conditions in the airways, such as altered electrolyte levels, thick mucus and an acidic environment has promoted bacterial pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, to establish itself in a biofilm rather than planktonic state, further contributing to the development of AMR, particularly when such bacteria are difficult to eradicate [8]. AMR continues to have a growing significant impact in patients with cancer, where infection is common and results in the second cause of death in this patient group. The burden of AMR is of concern in these patients due to implications for them, such as increased hospital admissions and deaths, as well as associated healthcare costs [9].

The primary aims of the BPPL are multi-fold, including a focus on research and development into the development of diagnostics and novel treatments, financial input, the development of AMR policies and programmes to promote active approaches to tackling AMR, the monitoring of resistance trends, as well as embedding affordable preventative and control measures.

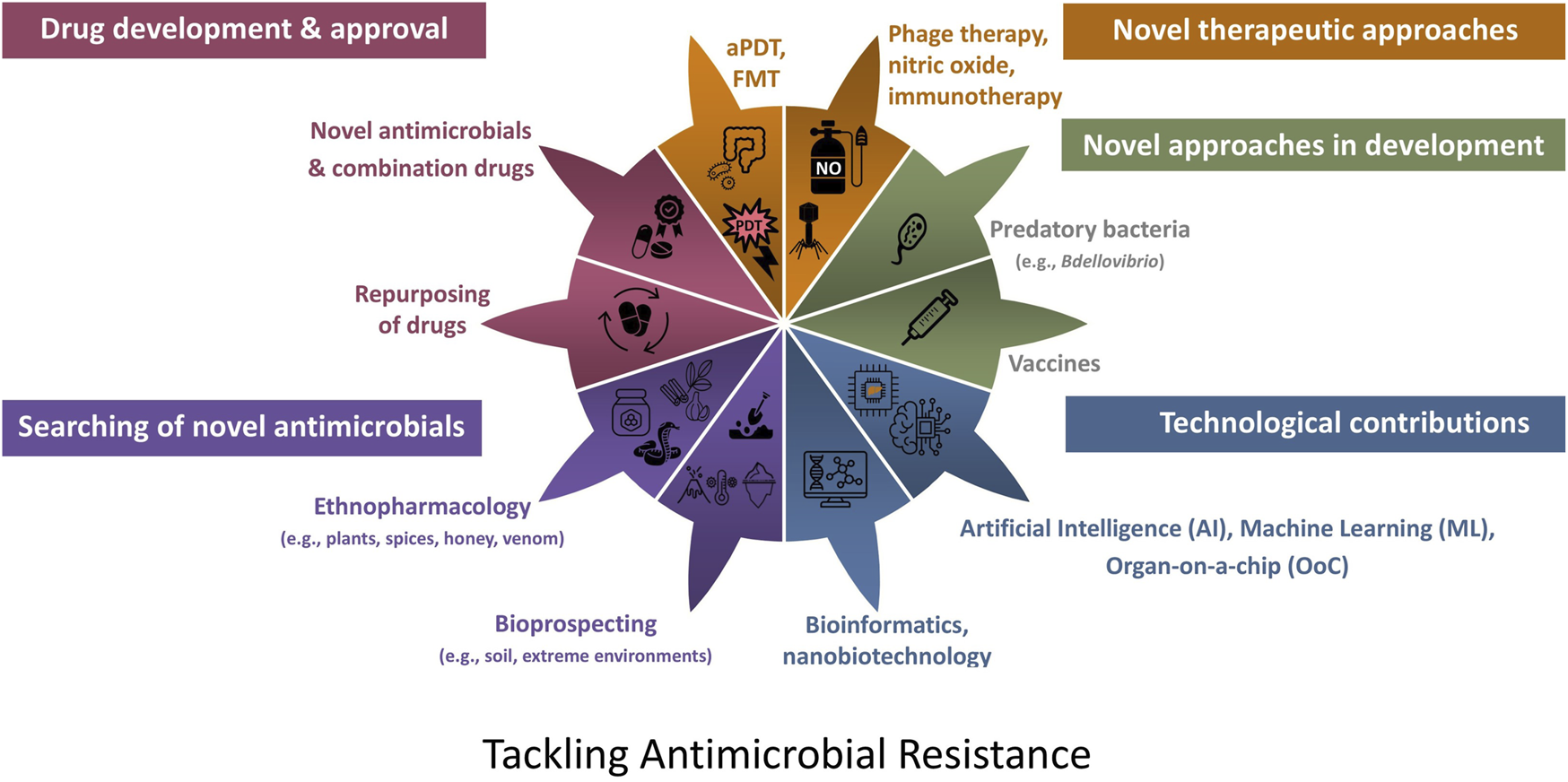

Due to the real-world difficulties in treating infections due to bacteria with multi-faceted resistance mechanisms, the aim of this narrative review is to provide an overview of research and clinical trials which have been or continue to be conducted, primarily during the last five years in relation to searching for and developing novel therapeutic approaches to target AMR infections. The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the wealth of approaches, i.e. the answers (Figure 2) which are currently being developed to tackle the therapeutic dilemma considering the AMR global crisis and to direct readers to seminal recent articles relating to each of these approaches to further enhance their understanding and appreciation of recent research and development.

FIGURE 2

Approaches which are currently being developed to tackle the therapeutic dilemma due to antibiotic resistance. aPDT, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy; FMT, faecal microbiota transplantation.

Novel Antibacterial Drugs & Drug Repurposing

Antibiotics commonly act at one or more of the various bacterial cellular sites such as those involved in the synthesis of cell walls, protein synthesis, nucleic acid synthesis, metabolic pathways and cell membrane function, and in the case of broad-spectrum antibiotics acting at cellular sites which are common to both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [10]. Key to the research and development of novel therapeutic approaches to the treatment of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is an understanding of the various cellular mechanisms of resistance, as well as the virulence factors attributed to such organisms, as the relationship between these, including the genetic regulation of these two components is intertwined [11].

As highlighted in the O’Neill review, research and development into novel antibiotics is challenging, primarily due to associated developmental costs and predicted lack of revenue from subsequent sales. This review stated that “The total market for antibiotics is relatively large: about 40 billion USD of sales a year, but with only about 4.7 billion USD of this total from sales of patented antibiotics”. Hence, coupled with the potential for the subsequent development of AMR, without incentives, the pharmaceutical industry is reluctant to invest in this market [1].

Recently Approved Antibiotics

Two recent seminal articles provide a comprehensive overview of the antibacterial drugs which have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) during the period 2012-2022 [12, 13] and it has been reported that only twenty antibiotics, seven β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations and four non-traditional antibacterial drugs have been launched worldwide during the last 10 years [14]. A recent evaluation of antibacterial drugs, particularly targeting those on the WHO priority list, which have been recently approved by the FDA and EMA, as well as those currently in the clinical trials pipeline, highlights that the majority of drugs are derivatives of currently available antibiotic classes and as such may succumb to similar resistance mechanisms which have been historically observed [15].

It is interesting to note two recent deemed “First-in- class” antibiotics approved, namely lefamulin and gepotidacin. Lefamulin (Xenleta™), is a semi-synthetic pleuromutilin and its mechanism of action is the blocking of bacterial ribosomal protein synthesis by means of interfering with the bacterial 50S RNA subunit [16]. Lefamulin was approved by the FDA (August 2019) and EMA (July 2020) followed by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), granting market authorisation in the UK in January 2021 for the treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. Until 2019, employment of pleuromutilins, was limited in human medicine to the topical treatment of impetigo and staphylococcal skin infections with retapamulin. However, market authorisation for retapamulin was withdrawn by the EMA at the request of the marketing authorisation holder, leaving the new antibiotic, lefamulin, as the sole agent within this class of antibiotic with a licence and indication in human medicine. The licensing of this pleuromutilin in human medicine creates a new dynamic, where the historical backdrop of pleuromutilins were exclusively a class of antibiotics used solely in veterinary medicine, with tiamulin and valnemulin, as licenced in the UK, for the treatment of swine dysentary caused by Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, complicated by the anaerobes, Fusobacterium and Bacteroides, as well as the atypicals, including Mycoplasma infections. Also, this class of antibiotic is typically used against Mycoplasma spp. and avian intestinal spirochetosis caused by Brachyspira in poultry [17]. The arrival of lefamulin in human medicine potentially creates a new route of transmission of pleuromutilin- resistance organisms developing in human medicine and spreading zooanthropogenically (reverse zoonosis) to livestock. As with other classes of antibiotics, cross-resistance may occur between other members of the pleuromutilin class and lefamulin [18].

Zooanthropogenic spread of bacterial pathogens has been documented, particularly with livestock and companion animals and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [19], with the potential to compromise the antibiotic efficacy of important classes of veterinary lincosamides, phenicols, streptogramins, as well as the veterinary pleuromutilins. The equilibrium of potential pathogen transmission involving the ebb and flow effect of zoonosis and anthroponosis coupled with AMR, creates a new dynamic for further investigation under the One Health initiative. This changing topography on the licensing of antibiotics for humans requires careful epidemiological monitoring of antibiotic susceptibility in both human and veterinary medicine, coupled with robust antimicrobial stewardship to ensure longevity of effectiveness with the pleuromutilins against AMR for both our human and animal patients.

Gepotidacin, was approved by the FDA on 25 March 2025 for the treatment of female and adolescent uncomplicated urinary tract infections. This antibiotic is a first in the class of triazaacenaphthylene antibiotics whose mechanism of action is inhibition of bacterial DNA replication by inhibiting the bacterial topisomerase enzymes, namely the B subunit of DNA gyrase (topoisomerase II), as well as topoisomerase IV [20]. This novel antibiotic has a number of properties of interest such as the availability of an oral medication, potential therapeutic use in the treatment of other infections due to its broad activity against Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms, including urogenital gonorrhoea, as observed in a recent clinical trial [21] and the fact that multiple mutations would be required in both enzymes to result in the development of resistance [20].

FDA Legislation to Promote the Development of Novel Antibiotics

In July 2012, The FDA Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA) became a regulatory legislation [22, 23]. One important aspect of this legislation was that the FDA could facilitate and expedite the development and review of new drugs. Title VIII within the FDASIA refers to “Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN)”. The primary aim of GAIN is to offer incentives to promote the development of certain antimicrobial drugs which can result in attainable concentrations in humans to either inhibit or kill fungal and bacterial infections such as those caused by antimicrobial-resistant organisms or emerging pathogens known to cause serious or life-threatening infections [24]. A drug which qualifies for a qualified infectious disease product (QIDP), will be granted two incentive policies: an additional 5 years of market exclusivity and a priority review during the review phase.

Following approval in June 2021 by The National Medical Products Administration, China [25], the FDA recently, September 2023, granted the pharmaceutical company MicuRX, a QIDP as well as fast track designation in relation to their oxazolidinone antimicrobial drugs contezolid (oral), and contezolid acefosamil (prodrug, intravenous) for the treatment of Gram-positive infections in severe diabetic foot infection without concomitant osteomyelitis [26]. Research is active in the potential use of contezolid in the treatment of several infections including tuberculosis due to its efficacy and safety profile [27], the treatment of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus infective endocarditis with cerebrovascular complications [28] and lung abscess due to S. aureus [29]. Interestingly, contezolid has been successful in the treatment of antibiotic-resistant infections such as skin infections due to MDR Mycobacterium abscesses complex bacteria [30], vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium pneumonia [31], MRSA catheter-related bloodstream infection [32], with further in vitro research ongoing in relation to antibiotic-resistant organisms including M. tuberculosis [33–37].

Combination Drugs

One key area where novel antibiotics have been developed relates to those with the potential to treat antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative organisms [38]. Development of combination drugs has been evident in an attempt to treat difficult and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Novel β-lactam and β-lactamase combination antibiotics have been an area of recent development and subsequent approval [39].

EMBLAVEO® (Pfizer, AbbVie) is the most recent FDA approved (07 February 2025) and EMA approved combination antibiotic for marketing authorization (22 April 2024). This combination antibiotic consists of the monobactam β-lactam aztreonam and avibactam which is a broad-spectrum β-lactamase inhibitor. This combination has been approved 39 years since the approval of aztreonam. EMBLAVEO® is effective against Gram-negative organisms such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, Enterobacter cloacae complex, Citrobacter freundii complex, and Serratia marcescens and is licensed to treat adult patients with complicated of intra-abdomenal infections, hospital-acquired pneumonia, ventilator-associated pneumonia, urinary tract including pyelonephritis, and aerobic Gram-negative infections which have limited treatment options particularly due to MDR [40]. Another recent antibiotic combination drug is sulbactam–durlobactam (XACDURO®) which is a β-lactam (sulbactam)/β-lactamase inhibitor combination (durlobactam) which was approved in May 2023 for the treatment of infections caused by Acinetobacter baumannii-calcoaceticus complex [41]. Cefepime/enmetazobactam (EXBLIFEP®; Advanz Pharma & Allectra Therapeutics) is an example of a novel antibiotic which received accelerated assessment via the MHRA International Recognition Procedure (IRP), resulting in approval within 55 days, on 4 April 2024, for the treatment of severe urinary tract infection and hospital-acquired pneumonia [42] and has potent antibacterial activity against Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL) Enterobacterales [43].

Several other combination antibiotic drugs developed approved over the last 10 years with a therapeutic indication for Gram-negative infections including imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam (RECARBRIO®; Merck Sharp & Dohme) [44], meropenem/vaborbactam (Vaborem®; Menarini) [45], ceftazidime/avibactam (Avycaz®; AbbVie) and ceftolozane and tazobactam (ZERBAXA®; Merck Sharp & Dohme) [46], the mechanism of action all of which relate to interference with the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall.

The scientific community continues to research combination antibiotics against antibiotic-resistant organisms such as K. pneumoniae [47]. Additionally, synergy testing of various multiple target antibiotic combinations offers guidance to clinicians when treating antibiotic-resistant organisms [48].

Drug Repurposing

Drug repurposing has extensive potential to accelerate the development of de novo antibiotic therapies and reduce the expense and failure rate for the application of such drugs against MDR bacterial infections, because safety and efficacy data already exist for other therapeutic applications [49]. Various approaches have been used to evaluate the potential antimicrobial repurposed drugs, including virtual screening and computational methods [50]. Recently a high throughput screening method which utilised a spectrophotometric approach prior to primary in vitro screening, for growth inhibition and anti-biofilm activity, was used by Pompilio and colleagues in the search for drugs with potential antimicrobial and antibiofilm properties against a MRSA strain from a patient with CF [51]. From this study, it was interesting to note that several antibacterial and antibiofilm compounds conventionally used as diuretic, anti-cancer, anti-asthmatic, anti-histaminic and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, were identified which warrant further investigation.

Repurposing research has primarily focused on MDR organisms and extended drug-resistant organisms such as A. baumannii [52], P. aeruginosa [53], M. tuberculosis and the non-tuberculous mycobacteria, such as M. abscessus [54]. A selection of such studies is detailed in Table 1. For a comprehensive appreciation, please see a recent review on the subject area [49]. In general, although research has indicated the potential of many of these proposed repurposed drugs, further research and clinical trials are warranted before such use becomes a reality.

TABLE 1

| Class drug | Action | Bacteria |

|---|---|---|

| Antidiabetic | | |

| Metformin [55] | Quorum quenching, decrease in motility | P. aeruginosa |

| Anticancer | | |

| VLX600 [56] | Iron chelator | Mycobacterium abscessus, E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa |

| Antidepressant | | |

| Paroxetine [57] Fluoxetine [57] | Inhibition of biofilm formation, synergy with levofloxacin | MDR P. aeruginosa |

| Antifungal | | |

| Ciclopirox [58] | Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity | P. aeruginosa |

| Antihelminthic | | |

| Albendazole [59] | Inhibition of quorum sensing, anti-virulence, anti-biofilm properties | P. aeruginosa |

| Antihistamine | | |

| Ebastine [60] | Bactericidal, antibiofilm, disruption of bacterial membrane/ increasing membrane permeability | S. aureus, MRSA |

| Fexofenadine [61] Levocetrizine [61] | Anti-quorum sensing, antivirulence potential | P. aeruginosa |

| Astemizole [62] | Disrupted bacterial membrane integrity, inhibited ATP synthesis, induced ROS accumulation | MRSA |

| Antipsychotic | | |

| Chlorpromazine [52] | Restoration of susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin Bactericidal activity, efflux pump inhibitor | PDR and MDR A. baumannii |

| Penfluridol [63] | Limited antibacterial activity alone, synergy with colistin. Enhanced outer/inner membrane permeability, inhibition and biofilm eradication | Colistin-resistant E. coli, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa |

| Antiviral | | |

| Ribavirin [58] | Antibiofilm activity | P. aeruginosa |

| Beta blocker | | |

| Propranolol [52] | Restoration of susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin | PDR and MDR A. baumannii |

| Calcium channel blocker | | |

| Fendiline [64] | Inhibition of essential lipoprotein trafficking pathways | Carbapenemase expressing A. baumannii |

| Amlodipine [53] | Reduction in biofilm formation | P. aeruginosa |

| Diuretic | | |

| Furosemide [58] | Anti-biofilm activity | P. aeruginosa |

| Immunomodulator | | |

| Fingolimod [65] | Bactericidal, inhibition of biofilm formation, disruption of cell permeability/integrity | S. aureus, MRSA, E. faecalis, S. agalactiae |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory | | |

| Aspirin [66] | Synergistic bactericidal activity with colistin Aspirin-colistin disrupted cell membrane | MDR P. aeruginosa |

| Ibuprofen [67] | Effects intracellular K+ flux and leakage resulting in destabilisation of cytoplasmic membrane | S. aureus |

| Diclofenac [68] | Increases oxidative stress and decreases type IV pili when used with colistin resulting in sensitization of resistant strains to colistin | PDR and MDR A. baumannii |

| Aceclofenac [61] | Anti-quorum sensing, antivirulence potential | P. aeruginosa |

| Statin | | |

| Atorvastatin [61] | Anti-quorum sensing, antivirulence potential, interference with proton-motive force | P. aeruginosa |

| Thrombopoietin receptor agonist | | |

| Eltrombopag [69, 70] | Bacteriostatic, antibiofilm, anti-persister effects | S. epidermidis, MRSA |

| Veterinary anti-parasitic | | |

| Nicolaides [71] | Impact bacterial catabolic pathways resulting in reduction of ATP thereby inhibiting bacterial division/growth. Inhibition of α-haemolysin secretion by S. aureus | Gram-positive bacteria MRSA, E. faecalis, VRE, S. agalactiae, S. suis, S. pneumoniae |

| Ivermectin [61] | Anti-quorum sensing, antivirulence potential | P. aeruginosa |

A selection of non-antibacterial drug repurposing studies, evidencing a direct antibacterial or synergistic or restoration effect in the presence of conventional antibiotics.

MDR, multi-drug resistant; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus PDR, pan-drug resistant; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

Novel Antimicrobials in Research and Development

Antimicrobial Peptides and a Novel Macrocyclic Peptide

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), are natural components involved in the innate defence response against pathogenic organisms and are found in plants, animals, amphibians, insects, humans and microorganisms [72]. AMPs have received much attention due to their direct antimicrobial properties as well as their potential modulation of both the innate and adaptive immune responses and regulation of inflammatory processes [73].

AMPs, have broad specificity and are comprised of 5–100 amino acids, typically 50, with a molecular mass of 2–7 kDa [74, 75]. The primary mode of antimicrobial action of these positively charged peptides, is due to their Arginine (Arg) and Lysine (Lys) amino acid residues, which allow for the selection of negatively charged microbial membranes and subsequent disruption of these membranes by means of hydrophobic or electrostatic interactions resulting in cell lysis [74, 75]. Additionally, AMPs may inhibit protein or nucleic acid synthesis, protease activity and bacterial cell division [75]. Duarte-Mata & Salinas-Carmona recently discussed the potential of AMPs for the treatment of intracellular bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis due to the ability of AMPs to kill such organisms by means of internalisation, penetration and the induction of peptides by infected cells and bacterial clearance by means of AMP immunomodulation [73]. This would be a novel focus of research as to date studies and clinical trials have focused on extracellular bacteria.

It has recently been reported that although over 3,000 AMPs have been discovered only seven (gramicidin D, daptomycin, vancomycin, oritavancin, dalbavancin, telavancin and colistin), all of which have originated from soil bacteria, have been approved to date by the FDA [76]. The concerns and limitations of AMPs as a potential therapy must be acknowledged, which may have contributed to their lack of approval. Adverse effects have included kidney injury as well as toxicity namely due to cytotoxic and haemolytic effects. Additionally, historically some AMPs have shown undesirable characteristics with respect to solubility and stability and poor efficacy or non-superiority in comparison to conventional antibiotic therapy [73, 75], which may be in part due to their degradation with blood proteases or by the binding with other proteins. As such consideration must be given to the mechanism of administration [73].

An interesting, novel class of antibiotic with narrow spectrum is a macrocyclic peptide targeting A. baumannii, is zosurabalpin which is due to enter Phase 3 clinical trials in late 2025/early 2026 [77]. Zosurabalpin, has been identified and optimised as a result of initial in vitro studies to elucidate its antibacterial and pharmacokinetic properties and subsequent in vivo animal studies. The mechanism of action of this novel class of antibiotic is blocking the transport of lipopolysaccharide from the inner membrane of A. baumannii to its destination on the bacteria’s outer membrane. [78]. This is of significance as zosurabalpin should not be affected by current known resistance mechanisms.

Antibiofilm Approaches & Inhibition of Quorum Sensing

The ability of communities of bacteria to form biofilms is problematic for many disease states and infections, e.g., infective endocarditis, lung infections in CF and infections associated with medical devices and implants. The biofilm matrix and intracellular signalling mechanisms, such as quorum sensing, between polymicrobial communities to control biofilm formation, and polymicrobial competition are important aspects to consider in relation to AMR. The composition of the biofilm such as the matrix and in particular the protective extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), coupled with metabolic dormancy of pathogens contained within the biofilm, is conducive to protection and intrinsic tolerance to antimicrobial agents. Polymicrobial communities within a biofilm may also contribute to the development and spread of AMR via horizontal gene transfer (HGT), as well as modulating antibiotic efficacy [79]. As knowledge continues to increase in relation to biofilm formation including at a genetic level and via quorum sensing, various groups have investigated novel anti-infective substances natural and synthetic as well as re-purposed drugs (see Table 1), with respect to antibiofilm activity and inhibition of the quorum sensing and associated modulation of virulence pathways, which do not require the eradication of bacteria [80]. Focus has been primarily associated with WHO priority pathogens including P. aeruginosa [80] and MDR A. baumannii [81].

Antibacterial Oligonucleotides

Antibacterial oligonucleotides are synthesised nucleic acid sequences designed to exert an inhibitory effect on bacteria by binding to intracellular RNA sequences through complementary base pairing [82]. This technology is based on regulatory gene silencing via antisense RNA which occurs naturally in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems. To induce an antimicrobial effect of these oligomers is a result of two mechanisms, namely, by the inhibition of microbial growth by targeting essential gene products [83, 84], or by the inhibition of AMR, by targeting resistance gene products and sensitising pathogens to traditional antibiotics [85–87]. Both applications are viable for combating AMR, the first by providing a new class of antimicrobials, and the second by inhibiting the expression of AMR phenotypes in vivo. The antimicrobial efficacy of these molecules is dependent on three key molecular properties; their resistance to degradation, their rate of bacterial cell penetration and their affinity for intracellular target RNAs. Much research in this field has focused on Peptide-conjugated Phosphorodiamidate Morpholino Oligomers (PPMOs) because they have a modified backbone consisting of linked morpholine rings that render them resistant to degradation by nucleases and the oligomer portion specifically binds to mRNA [88]. Membrane-penetrating peptides are conjugated to these oligonucleotides and generally consist of repeating sequence motifs of cationic and nonpolar amino acid residues, which facilitate bacterial uptake, particularly in the case of the membranes of Gram-negative bacteria [88]. PPMOs have been demonstrated to target highly conserved and essential genes such as those coding for acetyl carrier protein (acpP), which functions in lipid biosynthesis, and have been found to be highly effective for reducing bacterial load in mouse models of infection for a range of pathogens including E. coli, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa [83, 84]. Other gene targets include rpsJ coding for 30S ribosomal protein S10 whose function is to bind tRNA to the ribosomes and lpxC coding for the UDP-(3-O-acyl)-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase which is involved in lipid A (endotoxin) biosynthesis [88, 89].

Bactericidal PPMOs have also demonstrated anti-biofilm activity both in vitro and in vivo [83, 84, 88]. In animal models of disease, essential gene targeted PPMOs have not only been shown to inhibit the establishment of biofilm, most likely through growth inhibition of planktonic pathogens, but have also been associated with reduction in mass of previously established biofilm. These findings suggest that despite their large molecular weight, PPMOs can penetrate and act upon biofilms in ways that traditional antibiotics cannot. For AMR-targeted PPMOs, studies have shown effective silencing of transmissible carbapenem resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae, allowing restoration of antimicrobial susceptibility both in vitro and in vivo [86]. Similar findings of restoring susceptibility to β-lactam antibiotics have been noted for mecA mRNA targeted oligonucleotides [85]. mRNA targeting of highly expressed bacterial efflux pumps associated with broad spectrum resistance to fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, macrolides and β-lactams has also resulted in increased efficacy by reducing minimum inhibitory concentrations for these therapies in vivo [87].

To date, PPMOs as antimicrobials have not yet progressed beyond research stages and there are some limitations for antimicrobial applications of this technology that need to be addressed before progression into clinical practice. At present, high concentrations of these high molecular weight molecules are required for effective mRNA silencing in vivo, and the potential toxic effect of producing high concentrations of PPMOs systemically needs to be investigated more thoroughly. Another limitation, particularly with reference to resistance gene silencing, lies in the need to determine which AMR phenotype a pathogen is expressing prior to targeted therapy and having to stagger therapy because antibiotic administration prior to achieving an AMR gene silencing effect would be ineffective.

Nanomaterials

Nanomaterials commonly have at least one dimension or a basic unit in the three-dimensional space in the 1–100 nm range [90]. Nanotechnologies which utilise such nanoparticles (NP) offer several advantages due to their size including improved drug bioavailability due to an increased area of contact between the compound and the bacteria enhancing absorption and adsorption capabilities, and allowing for controlled release and stability [91].

Some NPs which possess hollow structures called nanocages or nanocapsules are designed to contain a drug to deliver and release, and can be made of different materials such as lipids, proteins, polymers, ceramics, silica or metals. It is also possible to use NPs made of materials that already possess antimicrobial activity such as metals, oxides, metal halides or bimetallic materials e.g. ZnO NPs, AgNPs which have demonstrated antibacterial properties against WHO priority pathogens [90].

NPs exert their antimicrobial effects via four main mechanisms; (i) the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the case of metal oxide NPs, which promote peroxidation and damage of the components of the bacterial cell such as polyunsaturated phospholipids in the cell membrane, protein deactivation, enzyme disruption and DNA damage which results in cell death; (ii) physical damage to the cell wall membranes as a result of sharp edges of the nanomaterial; (iii) binding materials on the bacterial cell wall resulting in a loss of the integrity of bacterial cell membranes and the efflux of cytoplasmic substances and (iv) the direct effect of released metal ions which can inhibit ATP production and DNA replication [92, 93].

Surface-functionalised nanocarriers/NPs have been developed with various other functional compounds such as, antimicrobial and antibiofilm compounds such as antibiotics, AMPs, protein, chitosan, ligands, small biomolecules, antibodies and DNA [91] which have shown high antimicrobial activity and synergistic effects against antibiotic resistant bacteria [94] particularly when photodynamic NPs are used [95].

The most frequently studied NPs are silver nanoparticles, AgNPs, which release Ag+ ions and which have a high antimicrobial activity targeting biofilms, the bacterial cell wall and cell membrane, electron transport, signal transduction and generating ROS which target DNA and proteins [96]. Due to these antimicrobial properties, such NPs can be adopted for anti-biofilm coating in the production of surgical implants e.g., in orthopaedics [97] or in the preparation of antimicrobial wound dressings which also promote healing [98]. Kalantari and colleagues highlight some concerns in relation to (i) toxic effects of Ag-NPs in terms of both environmental organisms and human health and (ii) the development of bacteria developing reduced susceptibility/resistance to Ag-NPs [98].

Further research is required to address the challenges relating to production of metal NPs such as Ag-NP in a safe, environmentally friendly and cost-effective manner, in addition to addressing the varied reports relating cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of some metal-NPs such as Ag-NP, TiO2-NP [99].

Natural Sources of Novel Antibiotics From the Environment

Soil

The soil is a rich source of bacteria and fungi which produce antibacterial and antifungal compounds and historically researchers have searched the soil microbiota in the goal to find such compounds, particularly those which have an antibacterial action to help in the drive against AMR [100]. One limitation, however, has been that not all such environmental organisms are culturable by routine culture media and incubation conditions. In order to address this limitation, iChip technology was developed, whereby environmental samples containing micro-organisms were placed in micro-chambers and subsequently placed into their natural environment for incubation [101]. Using such technology lead to the discovery of an uncultured bacterium and novel antibiotic, teixobactin [102]. Teixobactin, is a new class of antibiotic which has a dual action, namely inhibition of cell wall synthesis by binding to a highly conserved motif of lipid II (precursor of peptidoglycan), thereby inhibiting peptidoglycan synthesis as well as disruption of the cytoplasmic membrane [102]. Much interest and research has been conducted on this antibiotic as it only damages membranes which contain lipid II which negates toxicity in human cells. Also of note is that this antibiotic has shown minimal resistance [103].

More recently, an environmental bacterium Paenibacillus sp. was shown to exert a broad-spectrum antibacterial activity. Examination of this bacterial genome revealed the presence of a biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) of colistin and interestingly a BGC of a lasso peptide subsequently named, lariocidin (LAR) [104]. Lasso peptides, so called due to their structural knotted lasso shape, belong to the class of peptides which are synthesised ribosomally and are subsequently modified post-translationally RiPPs) [104]. LAR is of major interest due to several reasons, as it (i) is the first lasso peptide that targets the ribosome to interfere with protein synthesis, specifically by binding at a unique site in the small ribosomal subunit and interacting with the 16S rRNA and aminoacyl-tRNA, to inhibit translocation and induce miscoding, (ii) has low propensity mutations spontaneous resistance mechanisms; (iii) lacks toxicity towards human cells and (iv) has potent broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against organisms including A. baumannii [104, 105]

Ethanopharmacology

Phytochemicals, which are bioactive compounds from plants and numerous research studies have documented that these are a source of antimicrobial natural compounds due to their broad spectrum of activity both per se, as adjuvants and synergistic compounds, enhancing the activity of conventional antibiotics [106–108]. Chinese herbal medicine has shown potential in the treatment of infections including antibiotic resistant infections [108, 109]. Although the precise mechanisms of action are difficult to elucidate as approximately fifty herbs in different combinations are employed, research has identified in the case of coumarins, the blocking of anti-quorum sensing and biofilm formation e.g. [110] and efflux pump inhibition [108, 111].

Honey

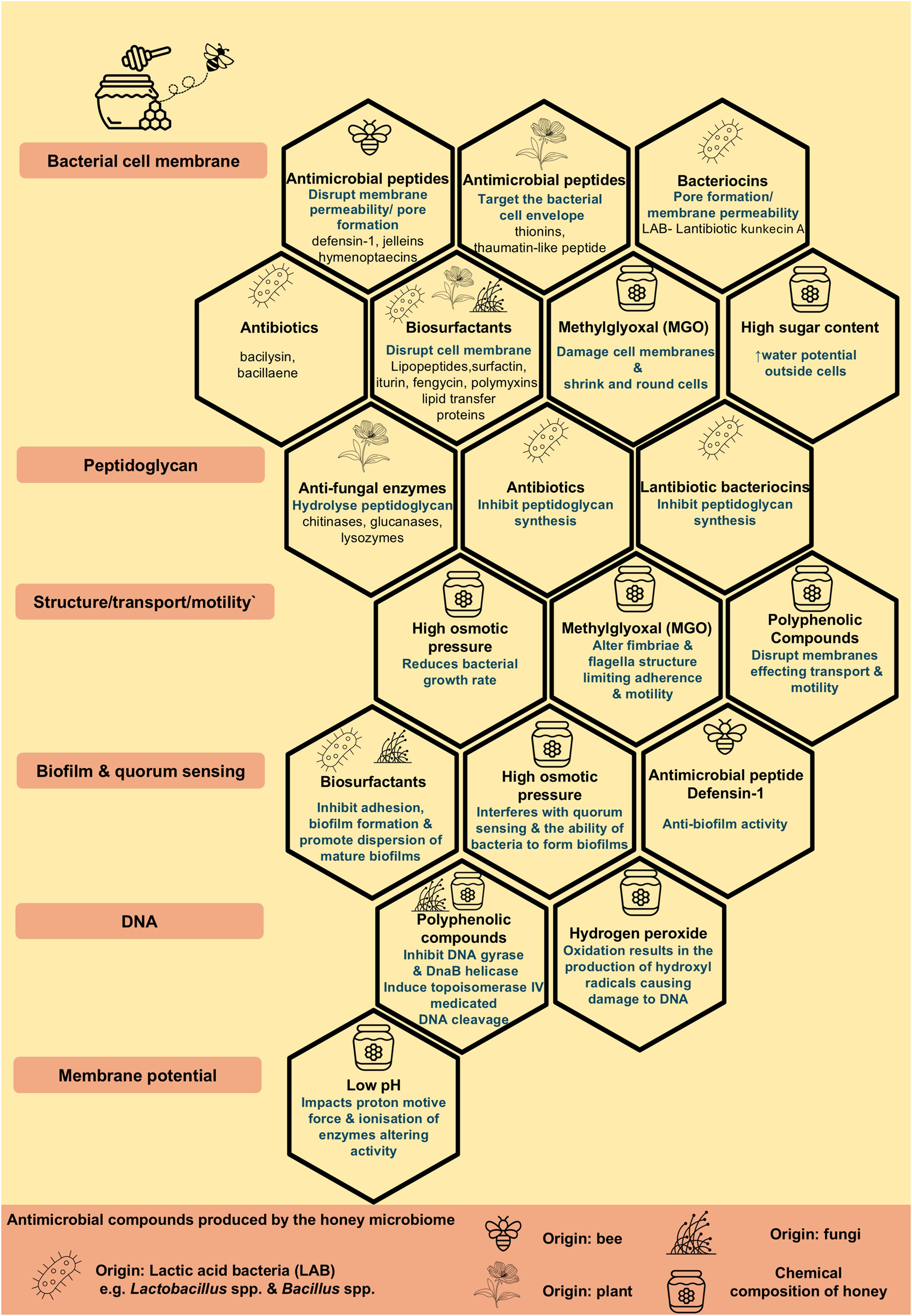

Honey, in particular Manuka honey, has had a rich history of being used to treat infections particularly in relation to wound infections [112], with several clinical trials currently ongoing for the treatment of wounds such as deep neck abscesses (NCT06562257), burn wounds (NCT03674151) and recent research has focused on the potential antibiotic effects of honey against antibiotic resistant pathogens both in human and veterinary medicine [113–115]. The antibiotic properties of honey have been attributed to its physicochemical properties, such as low pH, low water content and high osmolarity, as well as its composition of components including hydrogen peroxide, methylglyoxal (MGO), particularly in the case of Munuka honey from the Australian bush Leptospermum sp [116]. and defensin-1, as well as secondary metabolites originated from nectars, such as flavonoids and phenolic compounds [117–119]. The composition of honey varies depending on the botanical source, species of bee, geographical region and the microbiome of raw honey contributing to its physicochemical properties [120].

It must be realised however, that the antimicrobial effects shown by honey are not necessarily attributed to one particular compound and currently research is focusing on elucidating the mechanism of action of the diverse antimicrobial compounds found in honey many of which have been sourced from the bee, the plant/nectar and the associated microbiomes and microbial interactions [118]. A recent review by Brudzynski, 2021 [118] provides an interesting overview of the microbial ecosystem and the various antimicrobial compounds produced by the microbiome of honey, the honeybee, originating plants, bacteria and fungi. Such antibacterial compounds include ribosomal peptides, non-ribosomal peptides (NRP) peptides, namely antibiotics, lipopeptide surfactants, siderophores and polyketides from Bacillus sp. and bacteriocins and autolysins from lactobacilli (Figure 3) MGO has recently been incorporated into a novel liposomal formulation containing tobramycin which has shown active reduction in biofilm formation, as well as inhibition of bacterial adhesion highlighting the therapeutic antimicrobial potential of its components [121].

FIGURE 3

The composition of honey and antimicrobial compounds produced by the honey microbiome contributing to the antimicrobial properties of honey.

Spices and Essential Oils

Various spices have been examined for their therapeutic properties, antimicrobial activity and mechanisms of action [122], as well as their adjuvant activity in conjunction with conventional antibiotics against drug resistant organisms e.g., M. abscessus [123], polymyxin-resistant Klebsiella aerogenes [124] and P. aeruginosa [125] and Gram-negative organisms causing urinary tract infections [126]. Research has focused on not only pathogens which impact human health but also on the properties of spices which contribute to the prevention of foodborne pathogens, food safety and food preservation [127].

Venom

The potential antibacterial properties of venom from various sources have been shown against drug and MDR pathogenic bacteria. Most recently, honeybee venom has been demonstrated to be active against MDR pathogenic bacteria including, E. coli, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Enterococcus faecalis [128] and S. aureus [129]. Spider venoms have also been shown to contain a valuable resource of antimicrobial peptide toxins against pathogens such as S. aureus in the case of the Lynx spider Oxyopes forcipiformis [130]. The antibiotic potential of venoms including antimicrobial peptides sourced from jellyfish [131], scorpions [132, 133], wasps [134] and insects and centipedes [135], anti-biofilm substances from snake venom [136, 137] and antimycobacterial peptides from the venom gland of the cone snail Conasprella ximenes [138], have provided an evidence-base for future research into the search and development of novel antibacterial pharmacological agents.

Extreme Environments

Bioprospecting of extreme environments has identified various sources of antimicrobials [139]. Below a selection of examples show that all areas of earth are being explored in the quest to discover sources of novel antimicrobial compounds.

Antarctica, has been described as the coldest region on earth by NASA, where the hollows in the high ridge of the East Antarctic Plateau have recorded air temperatures of −94 °C and minimum surface temperatures of −98 °C [140] and yet it has been recognised as a valuable source of novel antimicrobials following microbial ecology [141] and genome mining [142, 143]. Indeed, potential therapeutic value of these novel antimicrobial compounds and source organisms, including bacteria, fungi, lichen, fish, seaweeds, sponges, krill, penguin and springtail have been recognised resulting in an increasing number of patents [144]. Antarctic fish/ice fish such as Notothenia coriiceps, Parachaenichthys charcoti, Trematomus bernacchii and Chionodraco hamatus, have been shown as a source of piscidins, which are antimicrobial peptides, with activity against particularly Gram-negative bacteria and MDR bacteria [145–149]. Other bacterial sources of novel, bioactive compounds, have been sourced from symbiotic bacteria colonised on Antarctic fish [150] and bacteria found in Antarctic marine soils [151, 152], sediment [153, 154], and Antarctica marine water [155] and fungi found in lichen [156] A recent study of interest showed supernatants from several Antarctic marine bacteria, whilst not antimicrobial per se, prevented biofilm formation and dispersal of biofilms produced by ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp.) [154]. Other antibiofilm proteins produced by Antarctic bacteria such as Pseudomonas spp. TAE608 [152] and Psychrobacter sp. TAE2020 [155] have also been reported.

Bioprospecting has led to the discovery of actinobacteria, with antimicrobial activity in the Kubuqi desert in China [157]. Streptomyces spp. found in the Saharan desert soils have been shown to produce a novel broad-spectrum antimicrobial which is a hydroxamic acid-containing molecule, with antagonistic properties against MDR pathogens [158]. The soil, in other remote areas such as caves in China, have been shown to comprise of Streptomyces spp. which produce xiakemycin A, which is a novel pyranonaphthoquinone antibiotic, with a strong inhibitory action against Gram-positive bacteria [159]. A wealth of research is ongoing in sourcing antimicrobials obtained from global extreme environments, such as nanoparticles from volcanic silica [160]; antibacterial activities and compounds including those which inhibit biofilm formation, from extremophile bacterial [161] and fungal [162] microorganisms, as well as shrimps [163] within deep-sea hydrothermal vents and systems. The high-altitude region in the Andes, namely the Lirima hydrothermal system, located in the northern region of Chile has been shown to be a source of secondary metabolites with antimicrobial activity produced by thermophilic bacteria. [164]. The halophilic environment is also being explored as a potential source of novel antimicrobial agents [165], with a recent study reporting that extracts from the soil from the Dead Sea in Jordan, had an antibiofilm activity against P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and S. aureus isolated from diabetic patients’ ulcerated wound infections of the feet [166]. The antimicrobial activity of the Dead Sea soil extract exerted a multifactorial action in that it (i) inhibited biofilm formation by reducing the production of extracellular substances and alginate; (ii) negatively impacted bacterial adhesion by decreasing surface hydrophobicity; (iii) disrupted preformed biofilms and (iv) disrupted outer bacterial membranes [166].

Phage Therapy

Clinical Application of Phage Therapy

Bacteriophages, or phages for short, are viruses which infect a bacterium and undertake a lysogenic or lytic pathway and can potentially transfer genetic material such as virulence and antibacterial resistance genes and lyse bacteria, respectively [167]. Bacteriophages have a number of characteristics which make them advantageous candidates to treat antibacterial resistant infections, such as their specificity in relation to bacterial hosts, the ability to cause bacterial death and their ubiquitous nature in that they are found in the environment as well as animals and humans, where the human gut phagosome has been shown to play a role in gut health and human disease. [167]. Furthermore, due to their natural existence within the human microbiome, it is assumed that using such bacteriophages for therapeutic purposes could be conducted safely and efficiently [168].

Of particular interest is the real-world application of phage therapy to treat or suppress infection. Within the scientific literature, generally such reports are confined to individual case studies and small cohorts, although there are several clinical trials and larger studies documented some of which are ongoing (Table 2), however valuable lessons can be learnt from such studies. The first reported clinical use of phage therapy to treat an infection was in 2017 in USA, when a multidrug-resistant A. baumannii infected pancreatic pseudocyst in a diabetic patient with a necrotising pancreatitis was successful, following a nine-phage cocktail administered intravenously and percutaneously into the abscess cavities [169]. This group subsequently established the Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics (IPATH), University of California, San Diego and published details of the outcomes of requests and ten cases which underwent intravenous phage therapy, in combination with systemic antibiotics, due to MDR and antibiotic-recalcitrant infections. The ten cases related to various infections due to S. aureus (n=2), E. coli (n=1), A. baumannii (n=2) and P. aeruginosa (n=5) [170]. The preferred route of administration was intravenous although one patient with pneumonia due to P. aeruginosa additionally received nebulised phage therapy and where possible a cocktail of phages was used to minimise the development of phage-resistance. The authors reported that such phage therapy was safe and following the initial administration at clinic, patients were administered their phage therapy at home. Furthermore, such phage therapy was not only successful as a treatment but as a suppressive therapy [170]. It is important to note that although bacterial resistance occurred in 3/10 patients, this was able to be successfully overcome by introducing additional phages which had matched with the resistant bacterial isolates.

TABLE 2

| Clinical Trials.gov ID | Condition | Phase | Status | Enrolment | Start date | Completion/ estimated date | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT06605651 | Hip or knee prosthetic joint infections due to Staphylococcus aureus | 2 | Not yet recruiting | 100 | 01/2025 | 01/2027 | Unknown |

| NCT06814756 | Morganella morganii prosthetic joint infection | 1/2 | Not yet recruiting | 1 | 24/02/2025 | 06/2026 | Canada |

| NCT06750588 | Acute alcohol-associated hepatitis (E. faecalis) | 1 | Not yet recruiting | 12 | 01/03/2025 | 12/2025 | USA |

| NCT06409819 | Recurrent urinary tract infections in kidney transplant recipients | 1/ 2 | Not yet recruiting | 32 | 01/06/2024 | 30/06/2027 | USA |

| NCT06942624 | Chronic Enterococcus faecium periprosthetic joint infection | 1/2 | Not yet recruiting | 1 | 05/2025 | 06/2026 | Canada |

| NCT05590195 | Urinary and vaginal health | 3 | Not yet recruiting | 50 | 01/05/2024 | 01/06/2025 | UK |

| NCT06370598 | Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 1/2 | Not yet recruiting | 15 | 09/2024 | 06/2025 | France |

| NCT06262282 | People with cystic fibrosis and non-tuberculosis mycobacteria pulmonary disease | Observational | Enrolling by invitation | 10 | 05/02/2024 | 12/2028 | USA |

| NCT05314426 | Mayo clinic phage program biobank | Patient registry | Enrolling by invitation | 100 | 19/04/2022 | 04/2027 | USA |

| NCT06938867 | Patients scheduled for allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation receiving fluoroquinolone prophylaxis and harbouring fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli pre-transplant | 1/2 | Recruiting | 240 | 25/02/2025 | 01/04/2026 | USA |

| NCT06559618 | Spinal cord injury patients with bacteriuria | 1 | Recruiting | 30 | 02/03/2025 | 12/2026 | USA |

| NCT05967130 | Chronic urinary tract infection post kidney transplant | 3 | Recruiting | 20 | 01/07/2023 | 01/07/2027 | Islamic Republic of Iran |

| NCT06870409 | Infective endocarditis | 3 | Recruiting | 30 | 05/02/2025 | 05/02/2029 | Russian Federation |

| NCT06185920 | Severe infections | Observational | Recruiting | 250 | 01/02/2023 | 01/02/2033 | France |

| NCT06319235 | Surgical site infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1/2 | Recruiting | 52 | 27/10/2023 | 31/12/2025 | Czechia |

| NCT04724603 | Phage safety retrospective cohort study | Observational | Recruiting | 25 | 01/02/2021 | 01/08/2022 | France |

| NCT05369104 | Prosthetic joint infection due to Staphylococcus aureus | 2 | Recruiting | 64 | 15/06/2022 | 16/06/2025 | France |

| NCT04650607 | Phage safety in treating prosthetic joint or severe infections | Observational | Recruiting | 100 | 09/05/2022 | 09/05/2028 | France |

| NCT06368388 | Difficult-to-treat infections | Observational | Recruiting | 50 | 01/06/2021 | 01/06/2025 | Belgium |

| NCT05177107 | Diabetic foot osteomyelitis | 2 | Recruiting | 126 | 24/11/2021 | 12/2024 | USA |

| NCT05948592 | Diabetic foot infection | 2 | Recruiting | 80 | 08/11/2023 | 31/12/2024 | USA/ India |

| NCT05488340 | Uncomplicated urinary tract infection caused by drug resistant E. coli | 2 | Recruiting | 318 | 13/07/2022 | 12/2025 | USA |

| NCT06456424 | Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infection | 1/2 | Active, not recruiting | 1 | 20/11/2024 | 11/2025 | Canada |

| NCT05182749 | Shigellosis | 1/2 | Active, not recruiting | 52 | 23/02/2023 | 30/06/2025 | USA |

| NCT05537519 | Urinary tract infection | 1/2 | Active, not recruiting | 1 | 01/05/2023 | 30/06/2024 | Canada |

| NCT06827041 | Periprosthetic joint infection | 1 | Active, not recruiting | 1 | 22/02/2024 | 02/2025 | Canada |

| NCT05010577 | Cystic fibrosis patients with chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa pulmonary infection | 1/ 2 | Active, not recruiting | 32 | 21/06/2022 | 03/2024 | USA/ Czechia/ Israel/ Netherlands/ Spain |

| NCT04682964 | Tonsillitis | 3 | Active, not recruiting | 128 | 02/10/2020 | 31/12/2028 | Uzbekistan |

| NCT06798168 | Periprosthetic joint infection of multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Expanded access | Available | - | - | - | Canada |

| NCT05453578 | Cystic fibrosis individuals chronically colonized with Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1/2 | Completed | 72 | 03/10/2025 | 10/04/2025 | USA |

| NCT05184764 | Bacteraemia due to Staphylococcus aureus | 1/2 | Completed | 50 | 26/24/2022 | 14/01/2025 | USA/ Australia |

| NCT05616221 | Subjects with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis and chronic pulmonary Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection | 2 | Completed | 48 | 10/01/2023 | 17/07/2024 | USA |

| NCT04684641 | Cystic fibrosis subjects with Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1/2 | Completed | 8 | 29/03/2021 | 26/05/2023 | USA |

| NCT04325685 | Effect of supraglottic and oropharyngeal decontamination on the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia and associated microbiomes | N/A | Completed | 60 | 01/01/2020 | 01/11/2023 | Russian Federation |

| NCT04596319 | Subjects with cystic fibrosis and chronic pulmonary Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection | 1/2 | Completed | 29 | 22/12/2020 | 14/12/2022 | USA |

| NCT05498363 | Difficult-to-treat infections | Observational | Completed | 100 | 01/01/2008 | 31/12/2021 | Belgium |

| NCT04803708 | Diabetic foot ulcers | 1/2 | Completed | 20 | 22/03/2021 | 07/08/2022 | Israel |

| NCT04191148 | Lower urinary tract colonization caused by Escherichia coli | 1 | Completed | 36 | 30/12/2019 | 19/11/2020 | USA |

| NCT04323475 | Wound infections in burned patients | 1 | Unknown | 12 | 01/2022 | 08/2023 | Australia |

| NCT02664740 | Diabetic foot ulcers infected by Staphylococcus aureus | 1/2 | Unknown | 60 | 01/06/2022 | 08/2024 | France |

| NCT04815798 | Prevention and treatment of Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae colonized pressure injuries | 1/2 | Unknown | 69 | 01/2022 | 12/2023 | USA |

Ongoing and recently completed clinical trials, within the last 5 years as of May 2025, relating to bacteriophage therapy to treat infections.

Although clinical successes have been noted with respect to phages in combination with systemic antibiotic therapy, there are ongoing in vivo studies investigating the mechanisms involved which could potentially lead to treatment success or failure, the findings of which have been conflicting. A recent article by Khosravi et al. serves as a critical evaluation of the phage therapy in an attempt to promote adjuvant therapy particularly in the case of individuals with chronic lung infections, such as those with CF, chronic pulmonary disease, non-CF bronchiectasis and individuals with chronic rejection following lung transplantation [171]. Khosvravi et al. details evidence to suggest a combination therapeutic approach can have a synergistic effect and that bacteria can be re-sensitised to antibiotics. In contrast, there have been studies evidencing phage-antibiotic antagonism in the form of phage resistance and enhanced antibiotic resistance, as such it has been proposed that phage therapy and antibiotic therapy should be staggered to minimise such resistance [171].

Is Phage Therapy for Difficult Infections a Reality Within the UK?

Due to the small number of case studies and limited clinical trials, in 2023, NHS Scotland considered a report from the Scottish Health Technologies Group (SHTG), in relation to “Bacteriophage therapy for patients with difficult to treat infections” [172]. The SHTG critically evaluated the evidence from the scientific literature and concluded that although there was a limited evidence-base relating to safety and clinical effectiveness of such therapy, and the lack of large-scale clinical trials, such therapeutic approaches have proven effective in individuals with infections which are difficult to treat with conventional antibiotics. Due to the lack of published cost-effectiveness studies, the SHTG undertook an economic modelling approach to evaluate the potential clinical use of phage treatment in conjunction with conventional care of refractory diabetic foot infections in individuals who were at high risk of lower extremity amputation and concluded this to be of a potentially cost-effective application of phage therapy. It was also recommended that the use of phage therapy in Scotland should be evaluated in terms of clinical effectiveness and safety to further inform decisions in future applications of phage therapy [172].

More recently, the House of Commons, UK Parliament, published a Committee report on 3 January 2024, by the Science, Innovation and Technology Committee relating to “The antimicrobial potential of bacteriophages”. The committee considered global witness from academia, clinicians, regulators, government officials and funding bodies in the format of oral presentations and written evidence on the safety, efficacy, manufacturing of phages, phage clinical trials and clinical use within the UK to date as well as evidence from global witnesses and site visits [173]. In summary, the House of Commons Science, Innovation and Technology Committee made eighteen recommendations, which comprised of four themes relating to phages namely, safety, efficacy and the UK phage research base, manufacturing of phages, clinical trials and the clinical use in the UK [173]. Subsequently, on the 1 March 2024, the UK government responded to these recommendations and the full policy paper can be viewed at the government website [174]. In summary, although the UK government accepted that the current evidence-base of phage therapy was promising, they believed that further evidence would be necessary to gain a full understanding of how such therapy could aid in combating AMR and that they would continue to work and support appropriate partners to achieve this aim. The UK government also indicated that phage therapy would be included amongst a range of various research areas in consideration for the treatment of AMR infections both in animals and humans, and the continued evidence will be reviewed and considered. They also highlighted what they considered to be the current limitations relating to the deployment of phage therapy in the UK which primarily related to “quality assurance, supply chain adequacy, financial approvals, health, safety and containment, and usage guidelines” [174]. A potential roadmap for the deployment of phage therapy within the UK has not been proposed by the UK government, however Jones et al. have proposed such guidance, particularly in relation to scalability and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) [175].

To date, phage therapy, is classified as a biological medicine, and is not licensed by the MHRA in the UK. Jones et al. discuss the regulatory situation in relation to phage therapy within in the UK and in short, phages may be used as unlicensed medicinal products also known as “specials” or “named patient” alternatives in accordance with MHRA guidance when conventional treatments are refractive, and the clinician deems an alternative therapeutic intervention is required [175]. If phages are imported for such clinical purposes, there is no requirement to be manufactured according to GMP, however, MHRA guidance must be adhered to. Phages manufactured in the UK for the purposes of clinical or investigational use must be manufactured according to GMP [175].

Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy (aPDT)

Light emitted at a precise wavelength in association with a photosensitizer (PS), can generate lethal photo-oxidative stress by producing detrimental forms of oxygen as radicals or reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in damage to cellular structures, such as membrane structure, and other components of pathogens such as DNA, cytoplasmic membrane proteins and lipids. Such damage alters cell wall synthesis, damages virulence factors and prevents replication and DNA synthesis [176]. Two types of photochemical reactions, result from activation of photosensitisers, namely Type I which result from the transfer of radical ions (such as superoxide anions (O2−), leading to the formation of various free radicals (including hydroxyl radicals HO˙, peroxyl radicals ROO˙ and alkoxyl radicals RO˙) and radical ions (radical cation of thymine or guanine) and Type II reactions which result in reactive singlet oxygen species, with both reaction types targeting various pathogen biomolecules [177].

To date there has been research into the application of this approach in relation to the treatment of skin cancers; however, there has also been research into the potential bactericidal and bacteriostatic role of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) in tackling ESKAPE pathogens and the AMR problem in the case of both prokaryotes and eukaryotes [178]. Piksa et al. have reported on studies, primarily in vitro, which have used the most common light source, methylene blue in the case of aPDT in relation to Gram-positive, (primarily S. aureus, E. faecalis, Streptococcus mutans), Gram-negative (primarily E. coli, P. aeruginosa, Porphyromonas gingivalis), fungal targets (primarily Candida species such as C. albicans, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis), as well as viral and parasitic targets [179]. Although not routinely used in clinical practice, primarily due to limitations of using this technology such as a lack of standardisation of protocols, varying light sources and the varied effectiveness of this approach, as of 2022 there were approximately 200 clinical trials using aPDT highlighting the interest and therapeutic potential of this technology [180], with current interest primarily relating to periodontal disease [181]. Table 3 details the most recent clinical trials which are examining the prevention of infection by nasal decolonisation, disinfection, as well as wound healing and tissue repair in the diabetic foot. Research has recently focused on areas which are central to aPDT, namely the depth of penetration and effectiveness of various light sources without resulting in thermal issues, such as laser, light emitting diodes (LEDs), lamp and non-coherent light sources, irradiance and radiance exposure values and also various photosensitizers, including those of both synthetic and natural origin, to ensure high tissue selectivity and that pathogens are selectively damaged rather than host cells [176]. Such research is important so that the potential of aPDT can be realised using light sources which are simple and cost-effective, yet clinically effective [179].

TABLE 3

| Clinical Trials.gov ID | Condition | Phase | Status | Enrolment | Start date | Completion/ estimated date | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT06777511 | aPDT to prevent infection in osseointegrated prosthesis patients | Observational | Not yet recruiting | 10 | 01/08/2025 | 30/08/2026 | USA |

| NCT06867458 | Nasal decolonization using aPDT on the prevention of hospital-acquired pneumonia, ventilator-acquired pneumonia and hospital-acquired bloodstream infection | N/A | Not yet recruiting | 400 | 31/03/2025 | 04/08/2025 | Canada |

| NCT06731881 | The efficacy of PDT for preventing surgical site infections in nasal surgery patients: a pilot study | N/A | Not yet recruiting | 80 | 01/01/2025 | 31/08/2025 | UK |

| NCT06570252 | Investigation of aPDT for preoperative nasal cavity decolonization in adult patients | N/A | Not yet recruiting | 208 | 10/2024 | 08/2026 | Switzerland |

| NCT06331442 | The effect of PDT on accumulation and bacteriological composition of dental plaque in orthodontic patients | N/A | Not yet recruiting | 50 | 05/2024 | 11/2024 | Croatia |

| NCT06702878 | Nasal antimicrobial photodisinfection for the prevention of surgical site infections | 3 | Recruiting | 4514 | 27/12/2024 | 07/2025 | USA |

| NCT06416462 | Action of aPDT on wound quality and tissue repair in the diabetic foot | N/A | Recruiting | 90 | 30/07/2024 | 31/06/2026 | Brazil |

| NCT05361590 | Impact of regular home use of lumoral dual-light photodynamic therapy on plaque control and gingival health | N/A | Completed | 40 | 11/10/2022 | 16/08/2023 | Finland |

| NCT06634745 | Evaluation of the effectiveness of aPDT using different irrigation activation techniques in teeth with apical periodontitis | N/A | Completed | 60 | 20/06/2023 | 14/07/2024 | Turkey |

| NCT05797818 | The effect of red light photobiomodulation and topical disinfectants on the nasal microbiome | 1/ 2 | Completed | 28 | 10/01/2023 | 08/02/2023 | USA |

| NCT05090657 | aPDT for nasal disinfection in all patients (universal) presenting for surgery at an acute care hospital for a wide range of surgical procedures | 2 | Completed | 322 | 04/02/2022 | 06/08/2022 | USA |

| NCT04047914 | aPDT in the nasal decolonization of maintenance haemodialysis patients | N/A | Completed | 34 | 01/11/2019 | 12/07/2021 | Brazil |

Ongoing and recently completed clinical trials, within the last 5 years as of May 2025, relating to antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) to treat and prevent bacterial infections.

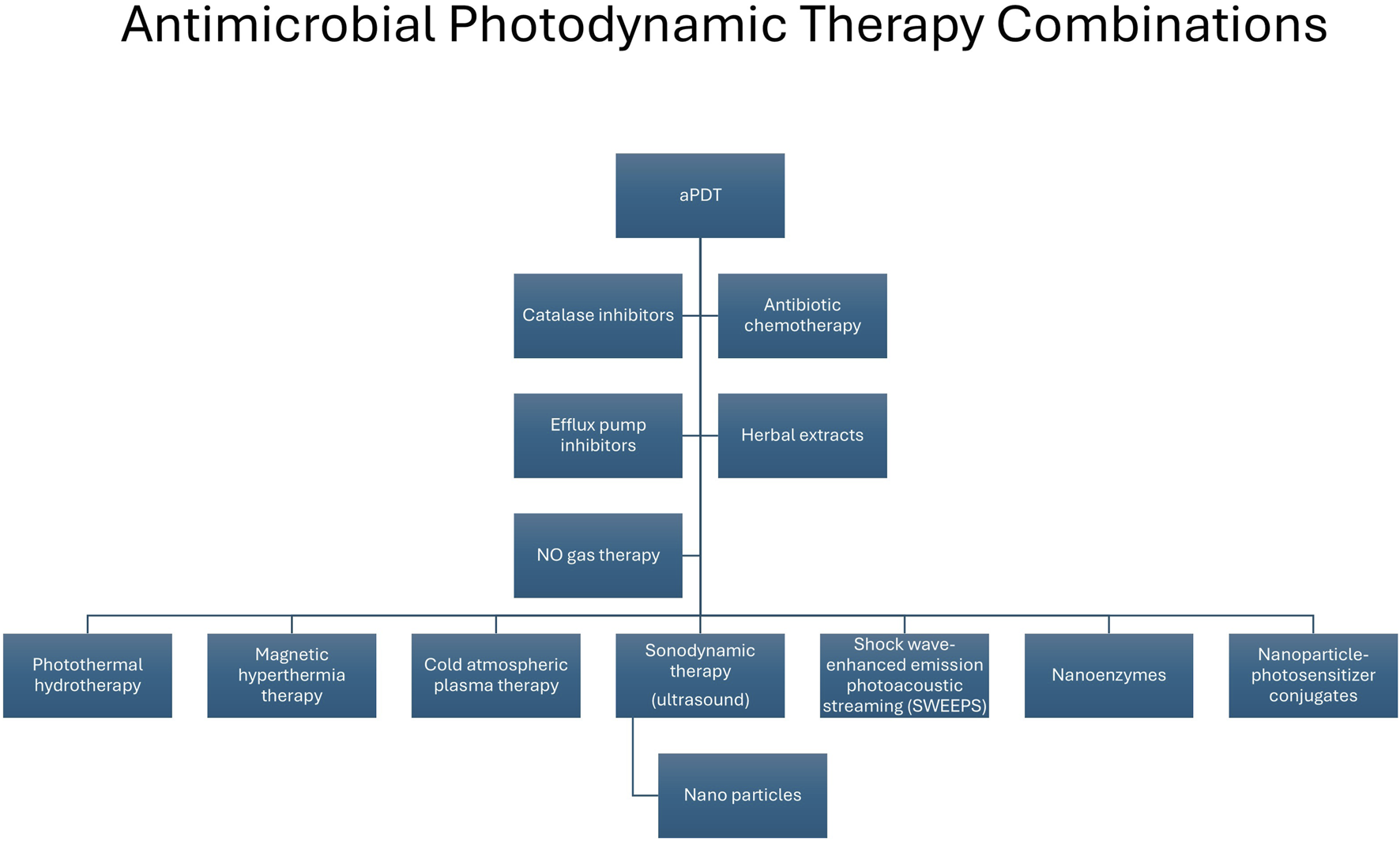

aPDT can offer several advantages in that it alone (i) can cause an antibacterial effect in the case of planktonic cells as well as targeting biofilms, (ii) offers limited development of resistance, due to the multiple sites and its mode of action; (iii) is effective against a broad range of pathogens, including MDR bacteria; (iv) has no toxicity, (v) is limited to target cells, (vi) can result in the reduction of virulence factors and pathogenicity and (vii) can result in a potential synergistic effect when used in conjunction with conventional antibiotic therapy and in combination with other therapies (Figure 4; [178, 181]). It must also be acknowledged that there are also some limitations to aPDT therapy including, (i) cost, (ii) weak antibacterial activity in the case of Gram-negative bacteria, (iii) solubility and (iv) specificity [176].

FIGURE 4

Combination approaches used in conjunction with antimicrobial photodynamic therapy to enhance antimicrobial activity. aPDT, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy; NO, nitric oxide.

Recently several studies have examined the effectiveness of aPDT against difficult-to-treat and MDR organisms [182] e.g. carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae [183]. Combination of aPDT with antibiotics have shown favourable and even synergistic results in the case of MDR organisms such as P. aeruginosa and S. aureus [184], with recent examples, including aPDT in combination with (i) gentamicin and imipenem in P. aeruginosa isolates [185], (ii) colistin against pan-drug resistant A. baumannii isolated from a patient with burns [186] and (iii) vancomycin against resistant E. faecium [187]. Other drug combinations currently undergoing research with aPDT include efflux pump inhibitors [188] highlighted by two recent studies, the first of which demonstrated an improvement in photo-deactivation of E. coli when the efflux pump inhibitor reserpine was used with methylene blue attached to a silver nanoparticle carrier [189]. The second study which used erythrosine B in conjunction with the efflux pump inhibitor verapamil and observed an augmentation effect in the inactivation of MDR planktonic strains of A. baumannii [190]. It has also been shown that aPDT in combination with quorum-sensing inhibitors resulted in synergistically inhibiting and dispersing the biofilm produced by MRSA [178] and a synergistic effect against S. aureus when used in combination with catalase inhibition [191].

It must be noted that several of these physicochemical combinations can be used in isolation or in combination with other therapies and nanoplatforms as antimicrobial approaches. For example, antimicrobial sonodynamic therapy (aSDT) uses low intensity ultrasound waves which can penetrate further than aPDT to a depth of 10 cm in soft tissues, to excite sonosensitizers to generate cytotoxic reactive species that are toxic to pathogens and acts by generating ROS, mechanical pressure and thermal effects [192]. aSDT alone and in combination approach with contrast microbubbles, has proven effective in inactivating both Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms [193], as well as enhancing antibiotic efficacy in the case of antibiotic-resistant bacteria [194] and eliminating biofilms [194]. Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that a co-ordination polymer nanoparticle (chlorin e6 (Ce6) with an antimicrobial peptide) in combination with aSDT had the ability to eradicate bacteria as well as exert an eradication of biofilm in the case of MDR-P. aeruginosa [195].

Nitric Oxide (NO)

Naturally, endogenous diatomic free radical nitric oxide (NO), is produced by the first-line innate immune response to invading pathogens. During oxidative bursts, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) enzymes in macrophages and neutrophils, facilitate the production of NO which subsequently results in the destruction of pathogens within phagosomes due to disruption of protein enzymes required for cell function, modification of membrane proteins and disruption of DNA via deamination.

Due to the multiple mechanisms of action of NO including (i) alternation of microbial DNA, (ii) inhibition of enzymes, (iii) modification of protein targets, (iv) damage to bacterial cell walls, cytoplasmic membranes and the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and (v) dispersal of biofilms, the development of resistance is difficult [196]. As such, its antimicrobial properties make it a valuable antimicrobial agent against infectious agents, particularly MDR bacteria. Although the antimicrobial properties of endogenous NO are well established, Webster and Shepherd (2024) have provided an interesting postulation and cautionary note in relation to the development of novel antibiotics, as they debate that NO may diminish the efficacy of some antibiotics or counteract antimicrobials which target bacterial energetics and elevate metabolism and bioenergetics as part of their bactericidal mechanism, yet they acknowledge evidence for the enhanced lethality of antibiotics in the case of biofilms, when used in conjunction with NO [197].

The off-label use of exogenous inhaled NO gas has been investigated for the treatment of respiratory infections in individuals with CF, which are commonly infected with multidrug resistant organisms [198], including P. aeruginosa [199], M. abscessus [200] and Burkholderia multivorans [201], as well as individuals with nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) pulmonary disease [202, 203]. Results were varied, ranging from reduction in colony forming units, improved lung function, improved antibiotic efficacy and a reduction in biofilm aggregates in the case of P. aeruginosa to improved quality of life and lung function, reduction in bacterial load but no eradication in the case of M. abscessus [196] and an improved antimicrobial susceptibility and clinical outcomes in the case of B. multivorans [201]. Due to the high reactivity and short half-life of NO (1–5 s) NO donors have been developed as well as delivery systems including nanoparticles, which have shown antibacterial and antibiofilm properties, however there are several areas which require further research in relation to potential toxicity issues, mechanisms to ensure controlled release as well as the optimising penetration of biofilms before its clinical use can be fully investigated [204].

A recent comprehensive article on the antimicrobial effects of nitric oxide by Okda et al. details further in vitro and in vivo studies as well as case studies, pilot studies, retrospective studies and clinical trials in relation to the potential and real-world therapeutic application in humans [196] and see Table 4 for current ongoing and recently completed trials.

TABLE 4

| Intervention | Clinical Trials.gov ID | Condition | Phase | Status | Enrolment | Start date | Completion date | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhaled nitric oxide | NCT06950294 | Critically ill patients with pneumonia | 1 | Not yet recruiting | 34 | 06/2025 | 10/2026 | USA |

| NOX1416; foam based gaseous nitric oxide | NCT06402565 | Chronic non-healing diabetic foot ulcers | 1 | Recruiting | 40 | 25/03/25 | 30/01/26 | USA |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | NCT06261827 | Prevention of nosocomial pneumonia after cardiac surgery | N/A | Recruiting | 160 | 20/02/2024 | 01/09/2025 | Russian Federation |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | NCT06170372 | Nosocomial & community acquired pneumonia | N/A | Recruiting | 200 | 15/02/2024 | 15/01/2026 | Russian Federation |

| Nitric oxide releasing solution (nasal spray) | NCT06264141 | Recurrent acute bacterial rhinosinusitis | 2 | Active, not recruiting | 162 | 16/01/2024 | 24/02/2025 | Bahrain |

| Inhaled nitric oxide agent, RESP301, via nebulisation | NCT06041919 | Adults with rifampicin susceptible tuberculosis | 2 | Active, not recruiting | 75 | 27/09/2023 | 31/07/2025 | South Africa |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | NCT06162455 | Prevention of nosocomial pneumonia after cardiac surgery | N/A | Completed | 74 | 17/11/2023 | 15/01/2024 | Russian Federation |

| Nitric oxide releasing solution | NCT04755647 | Diabetic foot ulcer | 1/2 | Completed | 40 | 23/02/2021 | 20/05/2023 | Canada |

| Intermittent inhaled nitric oxide | NCT04685720 | Nontuberculous mycobacteria lung infection in cystic fibrosis & non-cystic fibrosis patients | Pilot study | Completed | 15 | 07/12/2020 | 10/10/2022 | Australia |

| Nitric oxide releasing sinus irrigation | NCT04163978 | Chronic sinusitis | 2 | Completed | 56 | 27/20/2019 | 03/05/2022 | Canada |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | NCT03748992 | Pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection | 2 | Completed | 10 | 28/01/2019 | 26/03/2020 | USA |

Ongoing and recently completed clinical trials, within the last 5 years, as of May 2025, relating to nitric oxide therapy to treat infections.

Microbiome Manipulation

On 30 November 2022, the FDA approved REBYOTA®, the first live biotherapeutic faecal microbiota [205, 206], prepared from human stools donated by screened individuals and administered by enema, for the treatment of individuals ≥18 years following antibacterial treatment for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI). Subsequently, on 26 April 2023, the first oral therapy of faecal microbiota (VOWST™) was approved by the FDA [207]. CDI is often seen as a complication of antibiotic therapy, resulting in the disruption of the normal gut microbiota and is usually treated with metronidazole or vancomycin. However, with increasing drug-resistant strains, the incidence and even mortality rate of refractory CDI is increasing worldwide. In 10%–60% of cases, the infection returns after completing antibacterial therapy or may not subside at all. For such cases, faecal transplantation may be a considerably more effective option, preventing complications such as, colectomy where mortality rates have risen to 50% following this procedure [208]. Severe illness with CDI can ultimately be fatal, therefore it is essential to choose the correct treatment, and it has been proven that faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) can provide mortality benefit in critically ill patients, with 77% less mortality rates than with standard antibiotic care [208]. Such microbiome manipulation restores and harmonises the natural gut microbiota, replenishing bacterial balance.

The human gut microbiome generally has a good symbiotic relationship with the host providing (i) a defence against harmful pathogens through competitive exclusion by means of modulating the immune system and producing antimicrobials and (ii) nutritional benefits. The GI tract may also harbour opportunistic colonising pathogenic organisms and under certain conditions such as antibiotic use, acquisition of pathogens during hospitalisation, poor diet/nutrition, physical stress, mental stress, travel, pollution, age and pregnancy can result in a dysbiosis, thereby negatively impacting on the gut microbiota’s mechanisms to prevent the increase in the colonisation of harmful pathogens such as MDR organisms (MDROs), including ESBL producing Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) as well as contributing to the gut resistome [209].

The precise mechanism of FMT is yet to be determined, however it is speculated that the healthy donor gut flora repopulates the surroundings with normal gut flora with recent research showing that FMT is effective for decolonising [210, 211] and eradicating the carriage of drug and MDR bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes [212]. Such manipulation and modulation of the gut microbiota therefore has a potential role in the therapeutic challenges associated with AMR in terms of treatment and prevention [213].