Abstract

The global prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has increased significantly over the past decade and is projected to rise further. While genetic and lifestyle factors are well-established contributors to T2DM pathogenesis, mitochondria have also gained attention as the key players. Many studies suggested that mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations and epigenetic modifications were implicated in the development and progression of T2DM. This review aimed to provide a comprehensive analysis of mtDNA mutations and epigenetic modifications associated with T2DM. Based on data from 30 published studies, a total of 117 mtDNA mutations were identified to be associated with T2DM, with D-loop region being the mutation hotspot. However, it was reported that the majority of D-loop mutations were also more frequently observed in healthy populations compared to mutations in other mtDNA regions, suggesting their potential non-pathogenic characteristic. Thus, mtDNA mutations found to be associated with T2DM but with lower occurrence in healthy populations may play a more significant role in influencing T2DM susceptibility. Regarding epigenetic modifications, mtDNA methylation was commonly reported in the D-loop and ND6 regions across seven studies. These findings suggested that these regions may play critical roles in the regulation of mitochondrial gene expression under diabetic conditions. Lastly, this review also discussed the technical challenges and limitations of detecting mtDNA mutations and methylation changes. In addition, relevant ethical considerations surrounding mitochondrial genetic research were also addressed. In conclusion, mtDNA mutations and methylation changes could potentially serve as biomarkers for the development and progression of T2DM. These molecular modifications may offer valuable insights for early diagnosis and preventive strategies. However, further research and validation are essential to establish their clinical significance and diagnostic utility.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is recognised as one of the fastest expanding global health crises. In 2024, approximately 589 million adults aged between 20 and 79 were reported to have DM, which is estimated to increase to 853 million adults by 2050 [1]. Notably, around 90% of diabetes cases globally are attributed to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [2, 3]. Adding to this concern, T2DM incidence among individuals aged 15 to 39 rose by 56% between 1990 and 2019, further emphasising the urgent need to address this disease [4].

DM is characterised by increased blood glucose levels, often due to impaired insulin secretion from the pancreas, insulin resistance (IR) in peripheral tissues, or both [2]. Insulin is an important hormone secreted by the pancreatic β-cells, which facilitates glucose uptake from bloodstream into cells for energy production or storage [1]. Additionally, it plays a key role in inhibiting hepatic gluconeogenesis [5]. Therefore, reduced insulin production or sensitivity can lead to increased blood glucose levels.

It has been proposed that both genetic and epigenetic factors may influence the development of T2DM [6]. Although genome-wide association studies have identified several common genetic mutations associated with glycaemic traits (e.g., fasting glucose, fasting insulin, insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity), these account for only about 10%–20% of the variance in these traits [7]. This suggests that factors other than nuclear DNA may also play a significant role in T2DM development. In this context, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is thought to affect T2DM progression, in which mutations or epigenetic modifications in mtDNA may disrupt glucose homeostasis. Although studies have been conducted to determine mtDNA mutations related to T2DM, research on mtDNA epigenetic modifications remains limited and less well-documented.

Thus, this review summarises findings from 1994 to 2024 on the link between mtDNA mutations, epigenetic modifications, and T2DM, with most studies published within the past decade. The challenges and limitations to the profiling of mtDNA mutations and methylation have also been addressed. The discovery of mutations or epigenetic variations associated with T2DM susceptibility may enable earlier diagnosis or prevention. Additionally, mtDNA epigenetic profile may serve as a valuable indicator for assessing treatment efficacy or disease progression, contributing to a significant milestone in clinical advancement.

Mitochondrial DNA Mutations in the Development of T2DM

Mitochondria and Mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondria are frequently referred to as the “powerhouse of the cell” due to their essential role in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis through oxidative phosphorylation. They also play several crucial metabolic roles, such as intracellular calcium homeostasis, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, synthesis of haem and iron-sulphur clusters [8–10]. Furthermore, they play a central role in regulating programmed cell death by responding to the pro- and anti-apoptotic signals to maintain tissue homeostasis [11].

Mitochondria are distinct from other cytoplasmic organelles as they contain their own DNA, which encodes essential RNAs and proteins [12]. Human mtDNA encodes only 37 genes due to the evolutionary loss or transfer of most mitochondrial genes to nuclear DNA [13]. Among these, 22 genes encode for tRNAs, 2 rRNAs (12S and 16S) and 13 are protein-coding genes (Figure 1) [13]. Unlike traditional Mendelian genetics, mtDNA is inherited maternally as a haploid molecule, allowing mutant mtDNA to accumulate and be passed from mother to offspring [15, 16].

FIGURE 1

The human mitochondrial DNA. The outer circle indicates the H-strand, while the dotted line indicates the L-strand. Human mitochondrial DNA only encodes for 37 genes, namely 13 OXPHOS protein-coding genes, 22 tRNAs and 2 rRNAs [14]. H-strand: heavy strand; L-strand: light strand; OH: origin of H-strand synthesis; OL: origin of L-strand synthesis; HSP: promoter for transcription of heavy strand; LSP: promoter for transcription of light strand; bp: base pairs; D-loop: displacement loop: rRNA: ribosomal RNA; ND: NADH dehydrogenase; COX: cytochrome c oxidase; ATP: ATP synthase; Cyt b: Cytochrome b; tRNAs for F: Phenylalanine; V: Valine; L: Leucine; I: Isoleucine; Q: Glutamine; M: Methionine; W: Tryptophan; A: Alanine; N: Asparagine; C: Cysteine; Y: Tyrosine; S: Serine; D: Aspartic acid; K: Lysine; G: Glycine; R: Arginine; H: Histidine; E: Glutamic acid; T: Threonine; P: Proline; OXPHOS: oxidative phosphorylation.

Human mtDNA is a circular, polycistronic, double-stranded molecule made up of 16,569 base pairs (bp) and lacks introns (Figure 1) [17]. The nucleotide content of each strand differs, whereby the light strand (L-strand) is rich in cytosine, while the heavy strand (H-strand) is rich in guanine [17]. Next, mtDNA possesses a triple-stranded displacement loop structure known as displacement loop (D-loop), which is a non-coding region that acts as the promoter for both strands [18]. The D-loop regulates mtDNA replication, optimising the mtDNA copy numbers according to the cellular energy demands [19, 20].

Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

In mitochondria, ROS (e.g., superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals) are inevitably produced due to the continuous oxidative phosphorylation activity, accounting for approximately 90% of cellular ROS [21, 22]. Under normal circumstances, the cells possess defence mechanisms to counteract ROS generation [23]. For instance, the cells possess antioxidant enzymes that neutralise ROS, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione reductase, glutathione peroxidase, thioredoxin reductase, thioredoxin and peroxiredoxin [23, 24]. In addition to enzymatic antioxidants, mitochondria contain low molecular weight antioxidants (e.g., coenzyme Q) and repair mechanisms that help mitigate oxidative damage [23]. However, excessive ROS production can still be induced by stress factors, leading to excessive electrons being transferred to oxygen in the electron transport chain without ATP production [25].

Excessive ROS production has been implicated in causing oxidative damage to DNA, contributing to the development of various diseases [26]. It has been strongly associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, resulting in increased mutation rates, reduced mitochondrial biogenesis and accelerated aging [25, 27]. The ROS-induced mitochondrial dysfunction further suppresses ATP production while increasing ROS production, creating the ‘vicious cycle’ that ultimately leads to insulin resistance and onset of DM [25]. Additionally, excessive ROS disrupts the phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate proteins by serine kinases, which is a critical initial step in the insulin signalling pathway [28].

In turn, insulin resistance or DM can further disrupt the mitochondrial metabolism, causing reduced insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells, enhanced mitochondrial permeability transition, or increased mitochondrial apoptosis [29, 30]. Studies conducted on the relationship between mitochondrial mutations, mitochondrial dysfunctions and T2DM supported the involvement of mitochondria in T2DM development [31].

Mitochondrial DNA Mutations and T2DM

Mutation is a permanent and heritable alteration in DNA that often leads to changes in protein function [32]. It can also affect the structure and function of non-coding RNAs such as tRNA and rRNA [33]. Mutations may happen spontaneously or be induced by ROS. MtDNA is particularly susceptible to mutation due to its haploid nature and the close proximity to ROS production site, as aforementioned [21, 34]. Additionally, mtDNA lacks protective histones, leaving it more exposed to damage induced by ROS or other mutagens [21]. Moreover, unlike nuclear DNA, mtDNA lacks sufficient repair mechanisms to correct mutation and maintain normal mitochondrial function [35]. This susceptibility of mtDNA to mutation has led to the concept of a ‘vicious cycle’, in which initial ROS-induced mitochondrial dysfunction triggers further ROS production, subsequently exacerbating mitochondrial damage and dysfunction [21].

Recent studies have identified mtDNA mutations as potential contributors to the development of DM. Several mtDNA mutations associated with DM in various populations have been reported (Table 1). Beyond identifying mutations detected in diabetic individuals, it is equally important to determine whether these mutations also occur frequently in healthy individuals. Therefore, gnomAD 3.1 and Helix frequencies were included, which acted as the indicators of whether specific mutations are commonly found in healthy individuals, rather than exclusively in diabetic individuals [37–39]. In most cases, a mutation that appears at high frequency in healthy populations is likely a non-pathogenic polymorphism or mutation hotspot. Thus, the potentially significant mutations were highlighted in bold in Table 1, as they might be the more reliable indicators for different forms of DM.

TABLE 1

| mtDNA region | Mutationa | No. of haplogroups reported from PhyloTree 17.0 [36] | gnomAD 3.1 frequency (%)b [37, 38] | Helix Frequency (%)c [37, 39] | Patient report from Mitomap [37] | Population(s) identified by studies | Type(s) of DM/IR identified | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-loop | A16051G | 25 | 2.529 | 2.580 | N/A | Bangladeshi | T2DM | [40] |

| T16093C | 57 | 5.311 | 2.590 | N/A | Uyghur; Chinese; not specified | T2DM/MIDD | [41–44] | |

| T16126C | 21 | 14.321 | 17.653 | N/A | Bangladeshi; not specified | T2DM | [40, 44] | |

| G16129A | 93 | 11.526 | 7.282 | N/A | Bangladeshi | T2DM | [40] | |

| C16186T | 3 | 1.386 | NR | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] | |

| T16189C | 117 | 24.856 | NR | Reported DM | Italian; bangladeshi; caucasian; Chinese; not specified | T2DM | [40, 41, 46–48] | |

| C16223T | 33 | 39.409 | 18.185 | N/A | Bangladeshi; not specified | T2DM | [40, 49] | |

| C16270T | 18 | 8.836 | 7.629 | N/A | Moroccan | T2DM | [50] | |

| G16274A | 36 | 1.381 | 1.079 | N/A | Arab | T1DM/T2DM | [45] | |

| C16292T | 24 | 3.466 | 2.477 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] | |

| C16294T | 31 | 14.190 | 10.619 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] | |

| T16311C | 147 | 21.850 | 17.076 | N/A | Bangladeshi | T1DM | [40] | |

| G16319A | 39 | 6.228 | 4.645 | N/A | Bangladeshi | T2DM | [40] | |

| C16320T | 25 | 4.753 | 1.710 | N/A | Moroccan | T2DM | [50] | |

| T16519C | High | 65.725 | 64.287 | N/A | Italian; not specified | T2DM | [41, 46] | |

| T58C | 1 | 0.025 | 0.067 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM | [41] | |

| C150T | 76 | 16.628 | 10.078 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] | |

| C151T | 42 | 3.544 | 1.553 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM | [41] | |

| T195C | 124 | 27.606 | 17.602 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] | |

| 568 poly C | - | - | - | N/A | Not specified | MIDD | [41, 51] | |

| 12S RNA | T1189C | 3 | 4.005 | 5.965 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM | [49] |

| C1310T | 2 | 0.034 | 0.048 | N/A | Japanese; not specified | T2DM | [41, 52] | |

| A1382C | - | 0.066 | 0.079 | Reported T2DM susceptibility | Not specified | T2DM | [41] | |

| T1420C | 2 | 0.353 | 0.139 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM | [49] | |

| A1438G | 14 | 95.610 | 96.891 | N/A | Japanese | T2DM | [52] | |

| 16S RNA | G1719A | 28 | 4.033 | 5.127 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] |

| A1811G | 7 | 8.794 | 12.126 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM | [49] | |

| G1888A | 14 | 6.360 | 9.489 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] | |

| T2667C | - | 0.009 | 0.009 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM | [49] | |

| A2706G | 10 | 73.949 | 63.340 | N/A | Uyghur | T2DM | [43] | |

| T3027C | 8 | 0.236 | 0.366 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM | [49] | |

| A3156G | - | 0.007 | 0.007 | N/A | Not specified | T1DM/T2DM | [41] | |

| T3200C | 2 | 0.090 | 0.055 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM | [41] | |

| tRNA leu | A3243G | - | 0.000 | 0.001 | Confirmed pathogenic MELAS/MIDD | Chinese; Uyghur; Japanese; Indian; not specified | T1DM/T2DM/MIDD/GDM | [41, 43, 53–56] |

| C3254A | 1 | 0.243 | 0.041 | Reported GDM | Singaporean; not specified | GDM | [41, 57] | |

| C3256T | - | NR | NR | Confirmed likely pathogenic MELAS | Not specified | T2DM/MIDD | [41, 44] | |

| T3264C | - | 0.000 | 0.001 | Reported DM | Japanese; not specified | MIDD/MDM | [41, 58] | |

| T3271C | - | 0.000 | 0.000 | Confirmed pathogenic MELAS/DM | Chinese | T2DM/MIDD | [56] | |

| T3290C | 6 | 0.145 | 0.096 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM/MIDD | [41, 44] | |

| A3302G | - | 0.000 | 0.000 | N/A | Not specified | PCOS-IR | [41] | |

| ND1 | G3316A | 12 | 0.457 | 0.495 | hg D1, D2, M33, R30 markerd; reported DM | Indonesian; Mizo; not specified | T2DM | [41, 44, 59, 60] |

| G3357A | 2 | 0.044 | 0.059 | N/A | Not specified | T1DM/T2DM | [41] | |

| C3375A | - | NR | NR | N/A | Not specified | T1DM/T2DM | [41] | |

| T3394C | 8 | 0.911 | 1.085 | hg M9 markerd; reported DM | Chinese; Indonesian; Mizo; not specified | T1DM/T2DM | [41, 44, 48, 59, 60] | |

| T3398C | 7 | 0.239 | 0.270 | Reported GDM | Singaporean; not specified | GDM | [41, 57] | |

| A3399T | 2 | 0.005 | 0.009 | Reported GDM | Singaporean; not specified | GDM | [41, 57] | |

| G3483A | 6 | 0.190 | 0.173 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM | [44] | |

| T3548C | 4 | 0.034 | 0.036 | N/A | Not specified | MIDD | [41] | |

| C3970T | 2 | 0.588 | 0.581 | N/A | Mizo | T2DM | [60] | |

| tRNA Ile | G4284A | - | 0.007 | 0.001 | N/A | Not specified | MIDD | [41] |

| tRNA Met | A4435G | 2 | 0.041 | 0.066 | N/A | Chinese | T2DM | [56] |

| C4467A | - | NR | NR | N/A | Chinese | T2DM | [56] | |

| ND2 | G4491A | 8 | 0.298 | 0.384 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM | [41] |

| A4769G | 6 | 98.387 | 97.684 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] | |

| A5178C | - | NR | NR | N/A | Japanese; not specified | T1DM/T2DM | [41, 49] | |

| tRNA Trp | A5514G | 1 | 0.005 | 0.015 | N/A | Chinese | T2DM | [56, 61] |

| tRNA Ala | T5587C | 1 | 0.012 | 0.015 | Reported MIDD | Chinese | T2DM | [56] |

| T5628C | 1 | 0.096 | 0.086 | N/A | Chinese | MDM | [62] | |

| A5655G | 2 | NR | NR | N/A | Chinese | T2DM | [56] | |

| tRNA Cys/tRNA Tyr | A5826G | 1 | NR | NR | N/A | Chinese | T2DM | [63] |

| COXI | G5913A | 2 | 0.530 | 0.633 | N/A | Not specified | MIDD | [41] |

| C7028T | 2 | 74.940 | 63.008 | N/A | Uyghur | T2DM | [43] | |

| tRNA Ser | C7502T | - | 0.009 | 0.003 | N/A | Chinese | T2DM | [56] |

| T7505C | - | NR | 0.001 | N/A | Chinese | T2DM | [56] | |

| tRNA Lys | 8,281 9bp | 19 | NR | NR | N/A | Not specified | MIDD | [41, 51] |

| A8296G | 3 | 0.044 | 0.048 | N/A | Chinese | MIDD | [56] | |

| G8313A | - | 0.000 | NR | N/A | Indian; not specified | T2DM | [41, 53] | |

| A8344G | - | 0.000 | 0.000 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM/GDM | [41] | |

| A8348G | 2 | 0.094 | 0.151 | N/A | Not specified | MIDD | [41] | |

| T8356C | - | 0.000 | 0.000 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM | [41] | |

| ATP8 | C8478T | 2 | 0.486 | 0.704 | N/A | Not specified | MIDD | [41] |

| T8414G | 1 | NR | NR | N/A | Uyghur; not specified | T2DM | [41, 43] | |

| C8393T | 2 | 0.028 | 0.040 | N/A | Not specified | MIDD | [41] | |

| Region between ATP8 and ATP6 | T8551C | - | 0.018 | 0.020 | N/A | Not specified | MIDD | [41] |

| C8561G | - | NR | NR | Reported DM | Not specified | T2DM | [41] | |

| ATP6 | A8701G | 10 | 30.319 | 8.753 | N/A | Mizo | T2DM | [60] |

| A8860G | 4 | 99.381 | 98.774 | N/A | Not specified | MIDD | [41] | |

| COXIII | G9267C | - | NR | NR | Reported MIDD | Not specified | MIDD | [41] |

| T9540C | 1 | 30.433 | 8.791 | N/A | Mizo | T1DM | [64] | |

| A9827G | - | NR | NR | N/A | Not specified | T1DM | [41] | |

| tRNA Gly | T10003C | 1 | 0.025 | 0.068 | Reported MIDD | Chinese; not specified | T2DM/MIDD | [41, 56] |

| A10055G | - | 0.004 | 0.004 | N/A | Chinese | T2DM | [56] | |

| ND3 | A10398G | 24 | 41.848 | 25.166 | hg L, M markerd | Mizo; not specified | T2DM | [44, 64] |

| C10400T | 1 | 5.275 | 4.611 | N/A | Mizo | T2DM | [64] | |

| tRNA Arg | T10463C | 5 | 5.802 | 8.966 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] |

| ND4L | T10873C | 1 | 30.495 | 8.833 | N/A | Mizo | T2DM | [64] |

| G11696A | 6 | 0.099 | 0.135 | N/A | Chinese | T2DM | [65] | |

| G11914A | 48 | 10.858 | 5.329 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] | |

| A12026G | 4 | 0.108 | 0.096 | Reported DM | Japanese; not specified | T2DM | [41, 52] | |

| tRNA Ser | C12237T | 2 | 0.021 | 0.022 | N/A | Chinese | T2DM | [61] |

| C12258A | - | NR | NR | Confirmed likely pathogenic MIDD | Not specified | MIDD | [41, 66] | |

| tRNA Leu | A12230G | - | 0.000 | 0.000 | N/A | Chinese | T2DM | [56] |

| A12308G | 3 | 15.539 | 19.993 | Reported not pathogenic in hg K and Ud | Chinese | T2DM | [56] | |

| ND5 | C12633A | 4 | 1.271 | 1.893 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] |

| C12705T | 2 | 48.879 | 18.024 | N/A | Mizo | T2DM | [64] | |

| G13368A | 12 | 5.779 | 8.901 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] | |

| G13590A | 11 | 10.851 | 3.257 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] | |

| ND6 | G14364A | 12 | 0.489 | 0.614 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] |

| T14502C | 7 | 0.156 | 0.195 | N/A | Chinese | T2DM | [54] | |

| T14577C | 4 | 0.089 | 0.179 | Reported MIDD | Not specified | T2DM | [41, 49] | |

| tRNA Glu | A14692G | 1 | 0.002 | 0.009 | Reported MIDD | Chinese | MIDD | [67] |

| A14693G | 7 | 0.193 | 0.187 | Reported MELAS | Chinese; not specified | T2DM/MIDD | [41, 48] | |

| T14709C | - | 0.000 | NR | Confirmed likely pathogenic MIDD | Not specified | T2DM | [41, 44] | |

| Cytb | C14766T | 4 | 70.679 | 58.525 | N/A | Not specified | T1DM/T2DM | [49] |

| T14783C | 2 | 5.535 | 4.885 | N/A | Mizo | T2DM | [64] | |

| G15043A | 7 | 7.876 | 7.868 | N/A | Mizo | T2DM | [64] | |

| G15148A | 10 | 0.333 | 0.429 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] | |

| G15301A | 7 | 24.462 | 8.104 | N/A | Mizo; Arab | T2DM | [45, 64] | |

| A15326G | 9 | 99.342 | 98.973 | N/A | Not specified | MIDD | [41] | |

| A15607G | 4 | 5.558 | 8.735 | N/A | Arab | T2DM | [45] | |

| A15746G | 2 | 0.236 | 0.246 | N/A | Not specified | T2DM | [41] | |

| tRNA Thr | G15897A | - | 0.000 | NR | Reported MID | Chinese | T2DM/MIDD | [56, 68] |

| A15901G | 1 | 0.005 | 0.002 | N/A | Japanese | T2DM | [69] | |

| A15924G | 31 | 4.115 | 5.064 | N/A | Chinese; not specified | T2DM | [44, 56] | |

| C15926T | - | 0.012 | 0.028 | N/A | Japanese | T2DM | [69] | |

| G15927A | 7 | 0.709 | 0.920 | N/A | Chinese; not specified | T2DM | [44, 56] | |

| G15928A | 6 | 5.609 | 8.707 | N/A | Arab; not specified | T2DM | [44, 45] |

Summary of mitochondrial DNA mutations associated with diabetes or insulin resistance.

“TxxxxC” represents mitochondrial DNA, point mutation which occurs at position xxxx, where “T” is being replaced by “C”. “xxxx poly C″ represents that the polycytidine tract is variable in length at position xxxx. “xxxx xbp” represents mitochondrial DNA, insertion mutation which occurs at position xxxx, where a repeated sequence of x base pairs is inserted. All mutations positions are reported according to the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS, NC_012920.1). Haplogroup associations and presence in healthy individuals were determined using PhyloTree 17.0 and Mitomap. Mutations potentially significant in diabetes are highlighted in bold.

The gnomAD, 3.1 frequency refers to the variant frequency in healthy population based on the mitochondrial dataset from the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD v3.1). The frequency is derived from 70% Eurasian lineage (N), 25% African lineage (L) and 5% Asian lineage (M).

The Helix frequency refers to the variant frequency in healthy population based on the Helix population database. This frequency is derived from 91.2% Eurasian lineage (N), 4.2% African lineage (L) and 4.6% Asian lineage (M).

Mitochondrial haplogroup (hg) denotes specific maternal mtDNA, lineages. These markers indicate mtDNA, variants commonly found in specific maternal lineages and may represent population-specific polymorphisms rather than pathogenic mutations.

Haplogroup distribution, variant frequencies in healthy populations (as reported in public databases), clinical reports and examples of studies that observed these mutations in different populations were listed. T1DM: Type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; MIDD: maternally inherited diabetes & deafness/mitochondrial diabetes; MID: mitochondrial inherited diabetes; MELAS: mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; PCOS-IR: insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome; NR: not reported; hg: mitochondrial haplogroup (e.g., D1, D2, M33, R30, M9, L, M, K, U).

It was observed that while a majority of the mutations listed were located in the D-loop region, their frequencies in healthy populations based on both databases, were relatively higher compared to mutations in other regions of the mitochondrial genome. This suggests that many of the D-loop mutations linked to T2DM may represent random, non-pathogenic variants, rather than disease-causing mutations. This interpretation is supported by the fact that D-loop, which plays a key role in regulating mtDNA replication and transcription, is the most variable region of the mitochondrial genome in both healthy and diseased individuals [41]. Nevertheless, it is possible that D-loop mutations may still disrupt mtDNA replication, leading to mtDNA depletion and subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction, contributing indirectly to disease pathology [70].

While D-loop mutations are frequently observed in healthy individuals and likely non-pathogenic, certain other mutations may demonstrate a stronger disease association. For instance, one commonly affected site that is rarely found in healthy population is the tRNALeu gene, where adenine is substituted with guanine at nucleotide position 3243 (m.A3243G) [71, 72]. This mutation is also referred to as the mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) mutation, as it was initially identified in individuals with these clinical manifestations in 1990 [73]. This mutation disrupts the proper folding of tRNA molecule by interfering with key hydrogen bonds between A14 and U8, resulting in increased structural openness, reduced stability and reduced aminoacylation [74, 75]. To compensate, the mutant tRNA may abnormally form dimers with other mutant tRNA molecules, which further reduces the aminoacylation rate [74]. As a result, amino acids may be incorrectly incorporated or entirely omitted during mitochondrial translation, producing defective mitochondrial proteins and ultimately impairing mitochondrial function.

In summary, beyond identifying mutations present in diabetic individuals, it is equally important to assess whether these mutations also occur frequently in healthy populations. This distinction may further refine the understanding of specific genetic factors underlying mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetes, thereby contributing to more efficient risk detection. In this context, oxidative stress represents one of the key factors driving mtDNA mutations due to elevated levels of ROS in mitochondria. Thus, addressing oxidative stress and its effect on mtDNA mutations may offer promising strategies for the prevention or management of mitochondrial dysfunction in T2DM.

Mitoepigenetics in the Development of T2DM

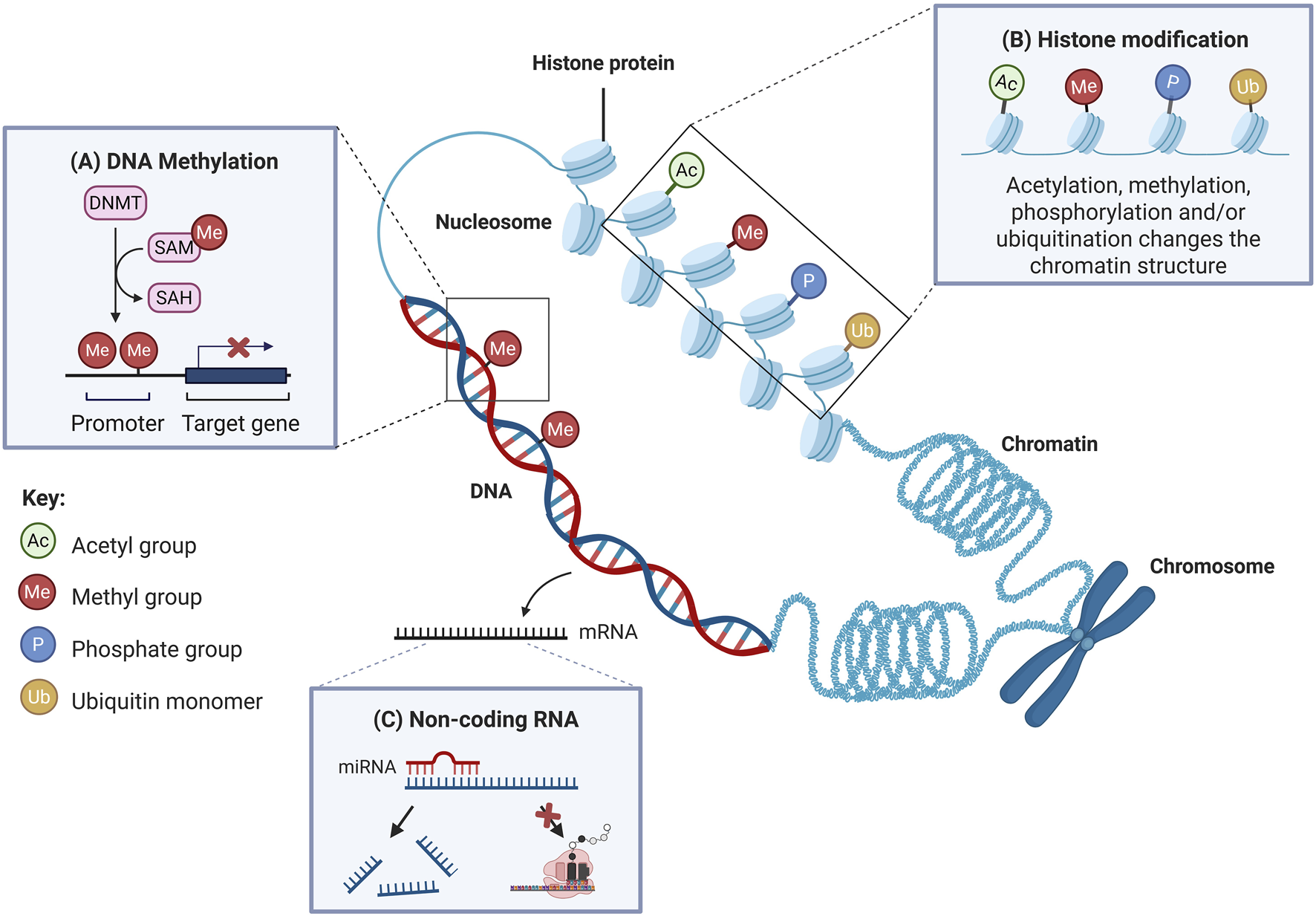

Epigenetics is the study of variations in gene expression that occur without DNA sequence alterations [76]. Key epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation, histone modifications and regulation of gene expression by non-coding RNAs (Figure 2) [79]. These mechanisms play important roles in regulating gene expression at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional and translational levels [80]. It is proposed that epigenetics not only occurs in nuclear DNA, but it also affects mtDNA, in which the phenomenon is known as “mitoepigenetics” [81]. The processes underlying mitoepigenetics have not been as thoroughly explored as those governing nuclear DNA, mainly due to the absence of histones in mitochondria [81, 82].

FIGURE 2

The primary mechanisms of epigenetics involve DNA methylation, histone modifications and regulation by non-coding RNAs. (A) DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of a cytosine residue. When methylation takes place at gene promoter regions, it usually leads to downregulation of gene expression. (B) Histone modification refers to post-translational modification of histone proteins, such as covalent addition of acetyl, methyl, phosphate groups or ubiquitin monomers. These modifications alter the chromatin structure and affect transcriptional activity. Histone acetylation and phosphorylation typically promote transcription, while methylation is often linked to transcriptional repression. Ubiquitination can either activate or suppress transcription, depending on the context. (C) Non-coding RNAs, such as miRNAs, regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally. When binding to target mRNAs, miRNAs either inhibit translation or promote mRNA degradation, thus silencing gene expression. DNMTs: DNA methyltransferases; SAM: S-adenosylmethionine; SAH: S-adenosylhomocysteine. Adapted and modified with permission from Low et al. [77]. Additional details from Liu et al. [78].

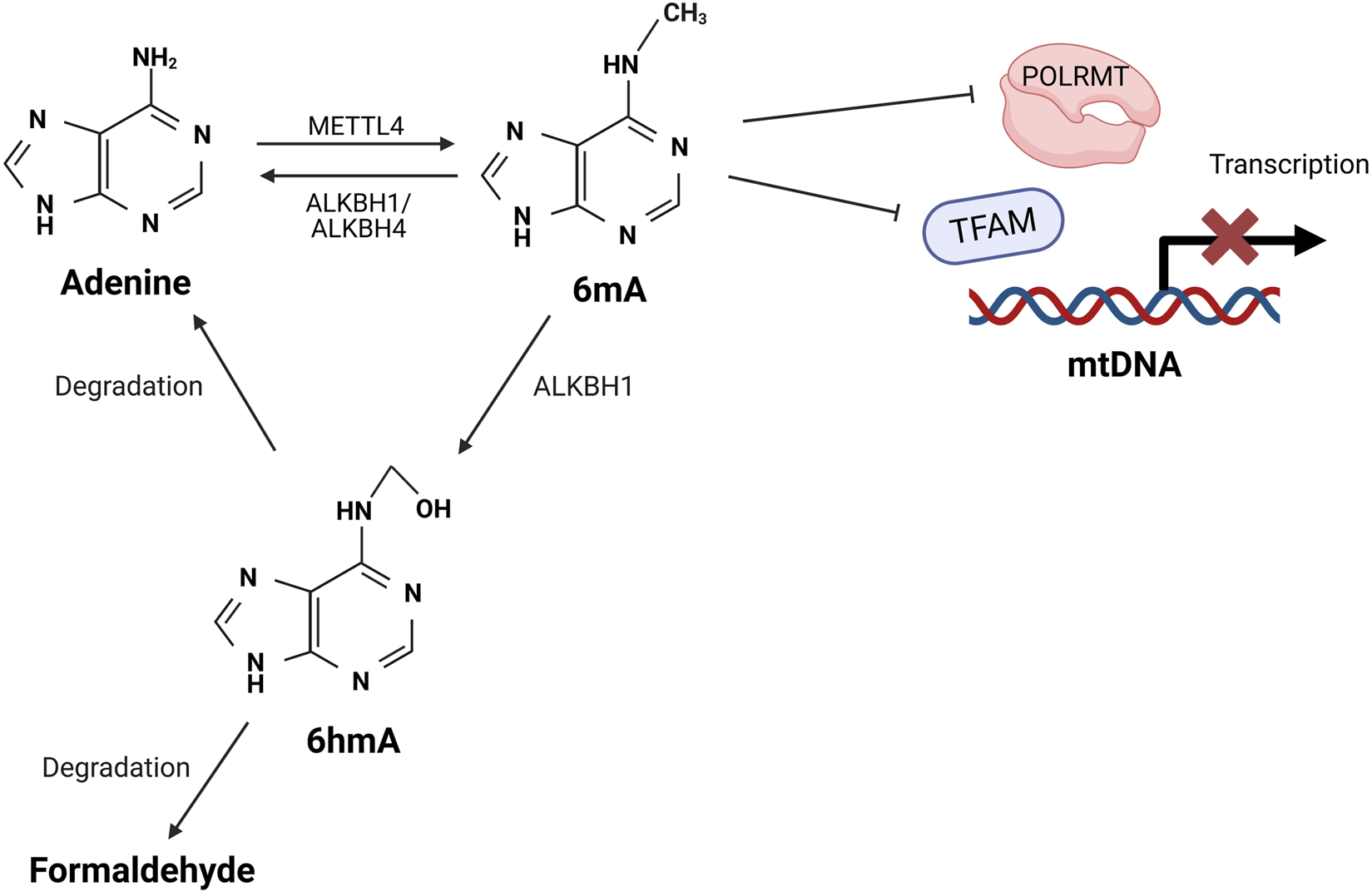

While some studies suggest that methylation is a distinct feature of nDNA and absent in mtDNA, others provide evidence supporting its presence in mtDNA [83–86]. Emerging studies have identified N6-methyldeoxyadenosine (6mA) as an alternative form of mtDNA methylation, mediated by methyltransferase 4 MTA70 (METTL4), alongside the more commonly studied 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) (Figure 3). Notably, the deletion of METTL4 has been shown to reduce 6mA levels in mtDNA [87]. However, studies have reported conflicting findings regarding the primary methylation sites in mtDNA, with evidence suggesting involvement of both CpG and non-CpG sites [92–95]. While the majority of studies suggest that methylation primarily occurs at CpG sites, Patil et.al. [93] reported that non-CpG sites are the main targets of methylation in mtDNA. Despite these conflicting findings, one consistent observation is that methylation occurs more frequently on the L-strand compared to the H-strand [93–96].

FIGURE 3

Proposed mechanisms of mtDNA methylation. Methyltransferase METTL4 catalyses the formation of 6mA on mtDNA, which interferes with the binding of TFAM and POLRMT with mtDNA, thus preventing the assembly of transcription initiation complex. This inhibition reduces mtDNA transcription and impairs mitochondrial function. The 6mA can be removed through oxidative demethylation mediated by ALKBH1 or AKLBH4, which restores adenine to its unmethylated form. Alternatively, ALKBH1 can oxidise 6mA to an unstable intermediate 6hmA, which rapidly degrades into formaldehyde and adenine [87–91]. METTL4: methyltransferase 4 MTA70; A: adenine; 6mA: N6-methyladenine; TFAM: transcription factor A; POLRMT: mitochondrial RNA polymerase; ALKBH: alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase homolog; 6hmA: 6-hydroxymethyladenine.

Several studies have suggested that mtDNA methylation serves as a protective mechanism against oxidative damage, which could potentially be induced by high blood glucose concentrations in patients with T2DM [97, 98]. The frequency and sites where mtDNA methylation have been detected in the progression of T2DM and related disorders are summarised in Table 2. An in vitro study showed that diabetic condition increased mtDNA methylation by 1.5- to 3-fold at various regions, including the D-loop, Cytb, ND6 and COXII [99]. Similar findings have also been reported by several in vivo studies. For instance, Kowluru (2020) found higher levels of D-loop methylation in the retinal microvasculature of T2DM rats [100]. Meanwhile, another study reported significant methylation at the ND1, ND2, ND6, CYTB and COX1 regions in diabetic mice [95]. The latter study also found significant higher methylation of ND6 in T2DM human subjects compared to healthy controls [95]. Notably, IR subjects displayed significant 4.6-fold increase in DNA methylation compared to insulin-sensitive subjects [103].

TABLE 2

| Experimental model | mtDNA Region(s) investigated | Key Observation(s) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell culture | |||

| High glucose (20 mM) treated in vitro cultured bovine retinal endothelial cells and human retinal microvasculature | D-loop, Cytb, ND6 and COXII | Increased methylation, decreased mtDNA transcription and increased DNMT1 binding were observed at D-loop. Methylation levels were significantly higher at D-loop compared to Cytb and COXII regions (p < 0.05). This resulted in significant inhibition of the mitochondrial gene expression critical for electron transport chain activity (p < 0.05) | [99] |

| Animal model | |||

| Hepatic mtDNA from db/db mice | 13 mtDNA-encoded genes | Significant methylation was observed at ND2, ND5, ND6, COX1 and ATP8 regions, with ND6 region showing the highest methylation level under diabetic conditions due to enhanced mitochondrial translocation of DNMT1 (p < 0.05) | [95] |

| Retinal microvasculature from T2DM, T1DM diabetes rat models, and high-fat diet rat models | D-loop | D-loop methylation level was higher in the T2DM group compared to the T1DM or high-fat diet group | [100] |

| Clinical studies | |||

| Peripheral leukocytes from 39 obese and 39 non-obese human subjects | ND6 | Significant increased ND6 methylation was observed in T2DM subjects compared to healthy controls. ND6 methylation level was inversely correlated with ND6 expression and positively correlated with metabolic parameters including body mass index, fasting glucose, fasting insulin and insulin resistance index (p < 0.05) | [95] |

| Buccal swabs from 69 young caucasian individuals | D-loop | D-loop methylation was significantly higher in overweight females than lean females. Increased methylation was associated with reduced mtDNA copy number, and mtDNA copy number showed a negative correlation with BMI in females (p < 0.05) | [101] |

| Leukocytes from fasting blood samples of 8 lean and 32 obese/overweight participants | D-loop and ND6 | D-loop and ND6 methylation levels were significantly correlated with insulin resistance indices (p < 0.05) | [102] |

| Leukocytes from fasting blood samples of 40 participants without diabetes or cardiovascular disease | D-loop | A 5.2-fold increase of D-loop methylation was observed in obese than in lean subjects; A 4.6-fold increase of D-loop methylation was observed in insulin-resistant than in insulin-sensitive subjects | |

| Liver biopsies from 45 NAFLD patients and 18 with near-normal histology | D-loop, ND6 and COX1 | Methylated/unmethylated ND6 ratio was significantly correlated with NAFLD activity score, whereas D-loop and COX1 methylation were not correlated with disease severity | |

mtDNA methylation studies in T2DM or related disorders.

Limited clinical research has been conducted to characterise the mtDNA methylation profile in T2DM subjects. However, since T2DM is often associated with obesity or being overweight, studying the methylation profile in such individuals may provide valuable insights. For example, a clinical study reported that increased methylation at specific CpG sites in the D-loop was significantly (p = 0.003) associated with body mass index (BMI) percentiles >85th in female subjects [101]. Similar observations were made in an earlier mixed-gender study, in which a 5.2-fold increase in D-loop methylation was observed in obese subjects compared to lean subjects [103]. This was further supported by a subsequent study that revealed a drastic elevation of methylation levels at ND6 and D-loop regions as BMI increased [102].

Research has also demonstrated the common coexistence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and T2DM. Specifically, NAFLD increases the risk of T2DM by 2- to 5-fold, with about 59.67% of T2DM patients also having NAFLD [104, 105]. This connection suggests that the methylation profile in individuals with NAFLD may be linked to T2DM. For instance, one study reported a significant positive association (p < 0.04) between the methylated-to-unmethylated ratio of mt-ND6 and the severity of NAFL, with methylation levels increasing from 20.6% in simple steatosis to 28.4% in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis [106].

In summary, increased mtDNA methylation is a response to various stress factors in disease states to protect mtDNA from damage and potential mutations. Several findings have indicated that mtDNA methylation profile contains relevant information about body composition and the associated risk of developing diseases such as T2DM. Given its roles in gene expression regulation, the potential of epigenetics in disease development or prevention warrants further research. Consequently, these epigenetic profiles might be a useful indicator for early molecular detection or prevention, as they are often detectable in the early stages of disease progression [107].

Limitations and Challenges in Sequencing Mitochondrial DNA Mutations and Mitochondrial Epigenetic Modifications

While research on mtDNA mutations and epigenetic modifications has advanced the understanding of mitochondrial regulation in T2DM, the accurate detection of these changes remains technically challenging. To date, hundreds of thousands of human mitogenomes have been sequenced using traditional Sanger methods, as well as a range of modern high-throughput sequencing platforms. Meanwhile, studies on the mitoepigenome remain limited but are getting increasing attentions with advancements in sequencing technologies. These sequencing technologies typically involve several steps including DNA isolation, library preparation and sequencing that uses various chemistries, flow-cells and detection systems utilizing base-specific color-coded fluorescence, light emissions, current, or ions changes. This is followed by bioinformatics analysis and each stage of the process presents unique challenges, making mtDNA sequencing particularly challenging.

Mitochondrial DNA Isolation and Purification

The initial step of isolating and enriching pure mtDNA relative to nuclear DNA remains challenging. Contamination with nuclear DNA, including mitochondrial pseudogenes in the lysate, can introduce artifacts during mtDNA analysis, particularly with short-read lengths [108]. Various conventional isolation techniques have been used, such as differential centrifugation, density gradient centrifugation, magnetic bead-based and mitochondrial isolation followed by DNA extraction [109–111]. Several commercial kits for direct mtDNA extraction are widely available. One study has also demonstrated a novel approach for mtDNA isolation and enrichment using a plasmid isolation kit, followed by additional purification with solid-phase reversible immobilisation on paramagnetic beads and limited polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification [112]. However, a very high cell number, typically ranging from 5 to 17 million cells is required from cell culture and patient samples to obtain sufficient mtDNA yield for sequencing, regardless of the method used [110, 112]. This requirement may be impractical for certain studies, particularly those involving clinical samples, which are often scarce.

Other options include DNA extraction followed by target enrichment of mtDNA by either long-range PCR amplification or complementary oligonucleotide probe hybridization. Targeted amplification may be suitable for direct sequencing but sequencing artefacts may be introduced during the DNA amplification, which may lead to false positive or negative results [113]. Moreover, mtDNA enrichment via PCR amplification is unsuitable for methylation sequencing, as PCR does not preserve methylation marks (such as 5-mC), compromising accurate quantification of mtDNA methylation [112, 114]. A mtDNA isolation method capable of providing high yield and enrichment with minimal or no amplification is ideal for downstream methylation sequencing and improvements are still needed in DNA extraction methods and protocols for investigation of epigenetic markers in an unbiased manner.

Sequencing Methods

Sequencing technologies are categorised into first-, second- and third-generation methods, with the latter two often referred as next-generation sequencing (NGS) [115]. The selection of an appropriate sequencing technology depends on the specific research question being asked. Different sequencing methods and platforms exhibit varying degrees of error rates, ranging from 0.1% to 5% as compared to the lower error rate of Sanger sequencing (0.001%) [113, 116–122]. Although these error rates might seem to be negligible, their cumulative effect can become significant given the vast size of the human nuclear genome [113].

Sanger sequencing (first-generation) is considered the gold standard due to its high accuracy despite its short-read limitations, but it is expensive compared to the newer technologies that have gained popularity, particularly for human whole genome sequencing [113]. These technologies have been increasingly integrated into clinical diagnostic practices, enabling a holistic analysis of genetic variants in targeted or complete genomes [123].

Besides characterizing genetic variants, it is worthwhile to study epigenetic changes, as epigenetic modifications can be influenced by external factors (e.g., lifestyle factors or intervention). If an individual is diagnosed with a particular genetic variant associated with a specific disease, epigenetic changes may be useful to control or switch off the expression of the specific gene through DNA methylation. By understanding both genetic variants and epigenetic changes in an individual or population, it is possible to offer a more targeted treatment which may potentially reduce the disease occurrence.

Bisulfite conversion with or without PCR amplification is generally used for methylation and mutation sequencing. In methylation sequencing, incomplete conversion of unmethylated cytosine to uracil followed by PCR amplification can lead to overestimation of methylation levels [124]. For mutation sequencing or other applications, biases may arise when short sequences or those with extreme GC content are preferentially or non-preferentially amplified [125]. Although reducing PCR cycles has been proposed as a strategy to minimise bias, research has shown limited improvement with an even lower correlation [125].

While methods such as bisulfite sequencing and methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) are commonly used to study epigenetic modifications, recent advances have enabled PCR-free sequencing approaches that bypass the need for bisulfite conversion. Platforms such as Illumina and Oxford Nanopore have been used for mtDNA sequencing, each offering distinct advantages and limitations (Table 3). Although PacBio technology has the potential to sequence full-length DNA without involving PCR amplification and bisulfite treatment, its application in detecting mtDNA methylation remains limited and underexplored in the current literature.

TABLE 3

| Sequencing methods | Epigenetic mark detected | PCR/Bisulfite conversion | Advantages | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | 5-mC | Yes | - Used mtDNA-specific primer sets to exclude nuclear mtDNA segments | - Required fragmented DNA. - Introduced bias due to bisulfite conversion and PCR amplification | [126] |

| 5-mC | Yes | [127] | |||

| 5-mC | Yes | [128] | |||

| Nanopore sequencing | 5-mC | No | - Enabled direct sequencing of linearised long read mtDNA or gDNA. - Excluded possible nuclear mtDNA segments from analysis - Overcame bias introduced by bisulfite conversion and PCR amplification - Detected both 5-mC and 6mA methylation marks | - Required high read depth to accurately detect methylation, increasing the cost | [96] |

| 5-mC | Both PCR-amplified and native mtDNA were used | [129] | |||

| 5-mC (applicable for 6mA) | Long-range PCR was used | [130] | |||

| 5-mC | No | [131] | |||

| Pyrosequencing | 5-mC | Yes | - Offered lower cost, suitable for validation studies - Provided precise quantification (%) of methylation at specific CpG sites | - Introduced bias due to bisulfite conversion and PCR amplification - Limited to short, targeted reads | [127] |

| 5-mC | Yes | [132] | |||

| 5-mC | Yes | [133] | |||

| 5-mC | Yes | [134] | |||

| PacBio single molecule real-time sequencing | 6mA | PCR was used | - Enabled direct sequencing of mtDNA or gDNA. - Overcame bias introduced by bisulfite conversion - Detected both 5-mC and 6mA methylation marks | - Potentially misidentified 5-mC as 6mA - Introduced bias due to PCR amplification | [135] |

Sequencing methods used for the detection of epigenetic modifications in mtDNA.

Data Analysis and Validation

After a successful sequencing run, the large volume of sequencing data requires extensive bioinformatics expertise for analysis to identify significant mutations or epigenetic changes. The computational analysis typically involves three essential steps: (1) Data processing and quality control to ensure accuracy, (2) Data visualisation and statistical analysis to identify patterns and trends, and (3) Validation and interpretation to confirm findings and assess their significance [136]. While minimising error rates remains a key objective for reliable results, ongoing optimisation is still required for different sequencing methods. Despite the availability of various analytical tools, a clear guideline for analysis settings and thresholds has yet to be established [136]. Different studies have adopted different approaches, often employing multiple software tools at different stages [137]. This lack of standardisation poses significant challenges in sequencing analysis. Additionally, comparing results across studies using different analysis methods can further complicate data interpretation.

Ethical Issues

Gene sequencing can reveal extensive genetic information, including adverse functional alleles of protein-coding genes and private individual variations that can be used to identify patients or their close relatives [138]. This raises ethical dilemmas regarding the disclosure of results to the individual or their relatives [139]. While increased awareness of potential hereditary conditions may promote healthier lifestyles, it can also lead to excessive anxiety or detrimental effect on individuals’ perspectives on their health and psychological wellbeing [140, 141].

In cases of maternally inherited mitochondrial diseases, caused by mtDNA mutations, several alternative strategies have been suggested to reduce or prevent the transmission of mtDNA from mother to child. These strategies include egg donation, prenatal testing, preimplantation genetic diagnosis and mitochondrial donation, all raising ethical concerns. Egg donation results in the child being genetically related to only one biological parent without the mitochondrial disease. Prenatal testing and preimplantation genetic diagnosis may risk the pregnancy and bring additional emotional burden on parents in deciding on whether to continue or prematurely terminate the pregnancy, if mitochondrial disease is detected [142]. Mitochondrial donation may be a more permissible approach as only the child’s mtDNA is replaced with mtDNA from a healthy donor while the nuclear DNA remain from both the biological parents [142]. However, concerns remain regarding the technical practicalities of complete faulty mtDNA replacement, as well as potential mismatches between the mtDNA haplotypes of the biological and donor mothers [142].

Conclusions

The increasing prevalence of T2DM in recent decades, along with its future projections and prevalence have raised global concerns. In response, numerous initiatives have been introduced worldwide to promote healthier lifestyles and lower the risk of T2DM. However, while lifestyle factors can have a significant impact on T2DM development, it is also essential to acknowledge the significant influence of inherited genetic factors. Although these genetic predispositions are difficult to alter, epigenetic mechanisms may offer a potential means to regulate harmful gene expression patterns that may contribute to the increased risk of developing T2DM.

This review highlights the emerging roles of mtDNA mutations and epigenetics in the pathogenesis of T2DM. Evidence suggests that alterations in mitochondrial gene expression and function may significantly impair metabolism, leading to T2DM. Given the interplay between inherited genetic predisposition and epigenetic regulation, future research should prioritise large-scale clinical trials to investigate these relationships and susceptibility to T2DM in diverse populations. By integrating genetic background and epigenetic modifications, a more advanced personalised treatment for T2DM could be developed to prevent the development and progression of T2DM.

Statements

Author contributions

The manuscript was written by MK. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia for the grant FRGS/1/2023/SKK10/UNIM/02/1 awarded to Y-FP. Sincere gratitude is also extended to the University of Nottingham Malaysia for providing full tuition fee waiver to MK.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work, MK used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4, https://chat.openai.com) to check for grammar and sentence clarity. The final content is reviewed and edited by the authors.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

References

1.

International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 11th ed. (2025). Available online at: https://idf.org/about-diabetes/diabetes-facts-figures/(Accessed June 5, 2025).

2.

GoyalRSinghalMJialalI. Type 2 Diabetes. Statpearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing (2023).

3.

RodenMShulmanGI. The Integrative Biology of Type 2 Diabetes. Nature (2019) 576:51–60. 10.1038/s41586-019-1797-8

4.

XieJWangMLongZNingHLiJCaoYet alGlobal Burden of Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Young Adults, 1990-2019: Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study (2019). BMJ (2022) 379:e072385. 10.1136/bmj-2022-072385

5.

SaltielARKahnCR. Insulin Signalling and the Regulation of Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Nature (2001) 414:799–806. 10.1038/414799a

6.

Galicia-GarciaUBenito-VicenteAJebariSLarrea-SebalASiddiqiHUribeKBet alPathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21:6275. 10.3390/ijms21176275

7.

GrarupNSandholtCHHansenTPedersenO. Genetic Susceptibility to Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity: From Genome-Wide Association Studies to Rare Variants and Beyond. Diabetologia (2014) 57:1528–41. 10.1007/s00125-014-3270-4

8.

PandaSBeheraSAlamMFSyedGH. Endoplasmic Reticulum and Mitochondrial Calcium Homeostasis: The Interplay With Viruses. Mitochondrion (2021) 58:227–42. 10.1016/j.mito.2021.03.008

9.

PicardMTrumpffCBurelleY. Mitochondrial Psychobiology: Foundations and Applications. Curr Opin Behav Sci (2019) 28:142–51. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.04.015

10.

YienYYPerfettoM. Regulation of Heme Synthesis by Mitochondrial Homeostasis Proteins. Front Cell Dev Biol (2022) 10:895521. 10.3389/fcell.2022.895521

11.

VringerETaitSWG. Mitochondria and Cell Death-Associated Inflammation. Cell Death Differ (2023) 30:304–12. 10.1038/s41418-022-01094-w

12.

CooperGM. The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd ed. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates (2000).

13.

GustafssonCMFalkenbergMLarssonN-G. Maintenance and Expression of Mammalian Mitochondrial DNA. Annu Rev Biochem (2016) 85:133–60. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014402

14.

YusoffAAM. Role of Mitochondrial DNA Mutations in Brain Tumors: A Mini-Review. J Cancer Res Ther (2015) 11:535–44. 10.4103/0973-1482.161925

15.

ProtasoniMZevianiM. Mitochondrial Structure and Bioenergetics in Normal and Disease Conditions. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22:586. 10.3390/ijms22020586

16.

GilesREBlancHCannHMWallaceDC. Maternal Inheritance of Human Mitochondrial DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (1980) 77:6715–9. 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6715

17.

ChinneryPFHudsonG. Mitochondrial Genetics. Br Med Bull (2013) 106:135–59. 10.1093/bmb/ldt017

18.

SharmaHSinghASharmaCJainSSinghN. Mutations in the Mitochondrial DNA D-loop Region Are Frequent in Cervical Cancer. Cancer Cell Int (2005) 5:34. 10.1186/1475-2867-5-34

19.

PereiraFSoaresPCarneiroJPereiraLRichardsMBSamuelsDCet alEvidence for Variable Selective Pressures at a Large Secondary Structure of the Human Mitochondrial DNA Control Region. Mol Biol Evol (2008) 25:2759–70. 10.1093/molbev/msn225

20.

BrownGGGadaletaGPepeGSacconeCSbisàE. Structural Conservation and Variation in the D-loop-containing Region of Vertebrate Mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Biol (1986) 192:503–11. 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90272-X

21.

BalabanRSNemotoSFinkelT. Mitochondria, Oxidants, and Aging. Cell (2005) 120:483–95. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001

22.

McCordJM. The Evolution of Free Radicals and Oxidative Stress. Am J Med (2000) 108:652–9. 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00412-5

23.

NapolitanoGFascioloGVendittiP. Mitochondrial Management of Reactive Oxygen Species. Antioxidants (2021) 10:1824. 10.3390/antiox10111824

24.

BhattiJSBhattiGKReddyPH. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Metabolic Disorders — A Step Towards Mitochondria Based Therapeutic Strategies. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis (2017) 1863:1066–77. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.010

25.

KimJWeiYSowersJR. Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Insulin Resistance. Circ Res (2008) 102:401–14. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165472

26.

LiuZRenZZhangJChuangC-CKandaswamyEZhouTet alRole of ROS and Nutritional Antioxidants in Human Diseases. Front Physiol (2018) 9:477. 10.3389/fphys.2018.00477

27.

Rovira-LlopisSApostolovaNBañulsCMuntanéJRochaMVictorVM. Mitochondria, the NLRP3 Inflammasome, and Sirtuins in Type 2 Diabetes: New Therapeutic Targets. Antioxid Redox Signal (2018) 29:749–91. 10.1089/ars.2017.7313

28.

Besse-PatinAEstallJL. An Intimate Relationship Between ROS and Insulin Signalling: Implications for Antioxidant Treatment of Fatty Liver Disease. Int J Cell Biol (2014) 2014:519153. 10.1155/2014/519153

29.

SivitzWIYorekMA. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Diabetes: From Molecular Mechanisms to Functional Significance and Therapeutic Opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal (2010) 12:537–77. 10.1089/ars.2009.2531

30.

HaythorneERohmMvan de BuntMBreretonMFTarasovAIBlackerTSet alDiabetes Causes Marked Inhibition of Mitochondrial Metabolism in Pancreatic β-Cells. Nat Commun (2019) 10:2474. 10.1038/s41467-019-10189-x

31.

RochaMApostolovaNDiaz-RuaRMuntaneJVictorVM. Mitochondria and T2D: Role of Autophagy, ER Stress, and Inflammasome. Trends Endocrinol Metab (2020) 31:725–41. 10.1016/j.tem.2020.03.004

32.

DurlandJAhmadian-MoghadamH. Genetics, Mutagenesis. Statpearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing (2022).

33.

XingGChenZCaoX. Mitochondrial Rrna and Trna and Hearing Function. Cell Res (2007) 17:227–39. 10.1038/sj.cr.7310124

34.

NeimanMTaylorDR. The Causes of Mutation Accumulation in Mitochondrial Genomes. Proc R Soc B (2009) 276:1201–9. 10.1098/rspb.2008.1758

35.

LiaoSChenLSongZHeH. The Fate of Damaged Mitochondrial DNA in the Cell. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res (2022) 1869:119233. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2022.119233

36.

van OvenMKayserM. Updated Comprehensive Phylogenetic Tree of Global Human Mitochondrial DNA Variation. Hum Mutat (2009) 30:E386–94. 10.1002/humu.20921

37.

LottMTLeipzigJNDerbenevaOXieHMChalkiaDSarmadyMet alMtdna Variation and Analysis Using Mitomap and Mitomaster. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics (2013) 44:1.23.1–23.26. 10.1002/0471250953.bi0123s44

38.

Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD). Broad Institute (2025). Available online at: https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/ (Accessed November 5, 2025).

39.

BolzeAMendezFWhiteSTanudjajaFIsakssonMJiangRet alA Catalog of Homoplasmic and Heteroplasmic Mitochondrial DNA Variants in Humans. BioRxiv (2020). 10.1101/798264

40.

SahaSKSabaAAHasibMRimonRAHasanIAlamMSet alEvaluation of D-loop Hypervariable Region I Variations, Haplogroups and Copy Number of Mitochondrial DNA in Bangladeshi Population with Type 2 Diabetes. Heliyon (2021) 7:e07573. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07573

41.

Al-GhamdiBAAl-ShamraniJMEl-ShehawiAMAl-JohaniIAl-OtaibiBG. Role of Mitochondrial DNA in Diabetes Mellitus Type I and Type II. Saudi J Biol Sci (2022) 29:103434. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2022.103434

42.

JiangZZhangYYanJLiFGengXLuHet alDe Novo Mutation of M.3243A>G Together with M.16093T>C Associated with Atypical Clinical Features in a Pedigree with MIDD Syndrome. J Diabetes Res (2019) 2019:5184647. 10.1155/2019/5184647

43.

JiangWLiRZhangYWangPWuTLinJet alMitochondrial DNA Mutations Associated with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Chinese Uyghur Population. Sci Rep (2017) 7:16989. 10.1038/s41598-017-17086-7

44.

BerdanierCD. Linking Mitochondrial Function to Diabetes Mellitus: An Animal’s Tale. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol (2007) 293:C830–6. 10.1152/ajpcell.00227.2006

45.

AlwehaidahMAl-KafajiGBakhietMAlfadhliS. Next-Generation Sequencing of the Whole Mitochondrial Genome Identifies Novel and Common Variants in Patients With Psoriasis, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Psoriasis With Comorbid Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biomed Rep (2021) 14:41. 10.3892/br.2021.1417

46.

NavagliaFBassoDFogarPSpertiCGrecoEZambonC-Fet alMitochondrial DNA D-Loop in Pancreatic Cancer: Somatic Mutations Are Epiphenomena While the Germline 16519 T Variant Worsens Metabolism and Outcome. Am J Clin Pathol (2006) 126:593–601. 10.1309/GQFCCJMH5KHNVX73

47.

PoultonJLuanJMacaulayVHenningsSMitchellJWarehamNJ. Type 2 Diabetes Is Associated With a Common Mitochondrial Variant: Evidence From a Population-Based Case-Control Study. Hum Mol Genet (2002) 11:1581–3. 10.1093/hmg/11.13.1581

48.

TangD-LZhouXLiXZhaoLLiuF. Variation of Mitochondrial Gene and the Association With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in a Chinese Population. Diabetes Res Clin Pract (2006) 73:77–82. 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.12.001

49.

Garcia-GaonaEGarcía-GregorioAGarcía-JiménezCLópez-OlaizMAMendoza-RamírezPFernandez-GuzmanDet alMtdna Single-Nucleotide Variants Associated With Type 2 Diabetes. Curr Issues Mol Biol (2023) 45:8716–32. 10.3390/cimb45110548

50.

CharouteHKefiRBounaceurSBenrahmaHReguigAKandilMet alNovel Variants of Mitochondrial DNA Associated with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Moroccan Population. Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp Seq Anal (2018) 29:9–13. 10.1080/24701394.2016.1233530

51.

JanssenGNeuA‘t HartLvan de SandeCAntonieMJ. Novel Mitochondrial DNA Length Variants and Genetic Instability in a Family With Diabetes and Deafness. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes (2006) 114:168–74. 10.1055/s-2006-924066

52.

TawataMOhtakaMIwaseEIkegishiYAidaKOnayaT. New Mitochondrial DNA Homoplasmic Mutations Associated With Japanese Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes (1998) 47:276–7. 10.2337/diab.47.2.276

53.

KhanIAShaikNAPasupuletiNChavaSJahanPHasanQet alScreening of Mitochondrial Mutations and Insertion–Deletion Polymorphism in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in the Asian Indian Population. Saudi J Biol Sci (2015) 22:243–8. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2014.11.001

54.

DingYZhangSGuoQZhengH. Mitochondrial Diabetes Is Associated With Trnaleu(Uur) A3243G and ND6 T14502C Mutations. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes (2022) 15:1687–701. 10.2147/DMSO.S363978

55.

KadowakiTKadowakiHMoriYTobeKSakutaRSuzukiYet alA Subtype of Diabetes Mellitus Associated With a Mutation of Mitochondrial DNA. N Engl J Med (1994) 330:962–8. 10.1056/NEJM199404073301403

56.

LinLZhangDJinQTengYYaoXZhaoTet alMutational Analysis of Mitochondrial Trna Genes in 200 Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Gen Med (2021) 14:5719–35. 10.2147/IJGM.S330973

57.

ChenYLiaoWXRoyACLoganathANgSC. Mitochondrial Gene Mutations in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract (2000) 48:29–35. 10.1016/S0168-8227(99)00138-2

58.

SuzukiYSuzukiSHinokioYChibaMAtsumiYHosokawaKet alDiabetes Associated With a Novel 3264 Mitochondrial Trnaleu(Uur) Mutation. Diabetes Care (1997) 20:1138–40. 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1138

59.

PranotoA. The Association of Mitochondrial DNA Mutation G3316A and T3394C with Diabetes Mellitus. Folia Med Indones (2005) 41:3–8.

60.

LalrohluiFThapaSGhatakSZohmingthangaJSenthil KumarN. Mitochondrial Complex I and V Gene Polymorphisms in Type II Diabetes Mellitus Among High Risk Mizo-Mongoloid Population, Northeast India. Genes Environ (2016) 38:5. 10.1186/s41021-016-0034-z

61.

YangLGuoQLengJWangKDingY. Late Onset of Type 2 Diabetes Is Associated With Mitochondrial Trna Trp A5514G and Trna Ser(Agy) C12237T Mutations. J Clin Lab Anal (2022) 36:e24102. 10.1002/jcla.24102

62.

LiKWuLLinWZhaoTQiQLiuJet alMutation at Position 5628 in the Mitochondrial Trnaala Gene in a Chinese Pedigree With Maternally Diabetes Mellitus. Res Square [Preprint] (2019). 10.21203/rs.2.17444/v1

63.

LiXShangJLiSWangY. Identification of a Novel Mitochondrial Trna Mutation in Chinese Family with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Pharmgenomics Pers Med (2024) 17:149–61. 10.2147/PGPM.S438978

64.

LalrohluiFZohmingthangaJhruaiiVKumarNS. Genomic Profiling of Mitochondrial DNA Reveals Novel Complex Gene Mutations in Familial Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Individuals from Mizo Ethnic Population, Northeast India. Mitochondrion (2020) 51:7–14. 10.1016/j.mito.2019.12.001

65.

DingYZhangSGuoQLengJ. Mitochondrial Diabetes Is Associated with the ND4 G11696A Mutation. Biomolecules (2023) 13:907. 10.3390/biom13060907

66.

LynnSWardellTJohnsonMAChinneryPFDalyMEWalkerMet alMitochondrial Diabetes: Investigation and Identification of a Novel Mutation. Diabetes (1998) 47:1800–2. 10.2337/diabetes.47.11.1800

67.

WangMLiuHZhengJChenBZhouMFanWet alA deafness- and diabetes-associated Trna Mutation Causes Deficient Pseudouridinylation at Position 55 in Trnaglu and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. J Biol Chem (2016) 291:21029–41. 10.1074/jbc.M116.739482

68.

LiKWuLLiuJLinWQiQZhaoT. Maternally Inherited Diabetes Mellitus Associated with a Novel m.15897G>A Mutation in Mitochondrial Trna Thr Gene. J Diabetes Res (2020) 2020:2057187. 10.1155/2020/2057187

69.

MiyamotoATomotakaUTakaakiKKenichiMChimiM. Molecular characterization of two pedigrees with maternally inherited diabetes mellitus. Mitochondrial DNA Part B (2022) 7:1724–31. 10.1080/23802359.2022.2050474

70.

DabravolskiSAOrekhovaVABaigMSBezsonovEEStarodubovaAVPopkovaTVet alThe Role of Mitochondrial Mutations and Chronic Inflammation in Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22:6733. 10.3390/ijms22136733

71.

ManwaringNJonesMMWangJJRochtchinaEHowardCMitchellPet alPopulation Prevalence of the MELAS A3243G Mutation. Mitochondrion (2007) 7:230–3. 10.1016/j.mito.2006.12.004

72.

GormanGSSchaeferAMNgYGomezNBlakelyELAlstonCLet alPrevalence of Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Mutations Related to Adult Mitochondrial Disease. Ann Neurol (2015) 77:753–9. 10.1002/ana.24362

73.

GotoYNonakaIHoraiS. A Mutation in the Trnaleu (UUR) Gene Associated with the MELAS Subgroup of Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathies. Nature (1990) 348:651–3. 10.1038/348651a0

74.

RahmadanthiFRMaksumIP. Transfer RNA Mutation Associated with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biology (Basel) (2023) 12:871. 10.3390/biology12060871

75.

HaoRYaoY-NZhengY-GXuM-GWangE-D. Reduction of Mitochondrial Trna Leu (UUR) Aminoacylation by Some Melas‐Associated Mutations. FEBS Lett (2004) 578:135–9. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.004

76.

PeschanskyVJWahlestedtC. Non-Coding Rnas as Direct and Indirect Modulators of Epigenetic Regulation. Epigenetics (2014) 9:3–12. 10.4161/epi.27473

77.

LowHCChilianWMRatnamWKarupaiahTMd NohMFMansorFet alChanges in Mitochondrial Epigenome in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Br J Biomed Sci (2023) 80:10884. 10.3389/bjbs.2023.10884

78.

LiuRWuJGuoHYaoWLiSLuYet alPost‐Translational Modifications of Histones: Mechanisms, Biological Functions, and Therapeutic Targets. MedComm (2023) 4:e292. 10.1002/mco2.292

79.

GibneyERNolanCM. Epigenetics and Gene Expression. Heredity (Edinb) (2010) 105:4–13. 10.1038/hdy.2010.54

80.

MoosaviAMotevalizadeh ArdekaniA. Role of Epigenetics in Biology and Human Diseases. Iran Biomed J (2016) 20:246–58. 10.22045/ibj.2016.01

81.

ManevHDzitoyevaS. Progress in Mitochondrial Epigenetics. Biomol Concepts (2013) 4:381–9. 10.1515/bmc-2013-0005

82.

CoppedèFStoccoroA. Mitoepigenetics and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2019) 10:86. 10.3389/fendo.2019.00086

83.

HongEEOkitsuCYSmithADHsiehC-L. Regionally Specific and Genome-wide Analyses Conclusively Demonstrate the Absence of Cpg Methylation in Human Mitochondrial DNA. Mol Cell Biol (2013) 33:2683–90. 10.1128/MCB.00220-13

84.

SainiSKMangalharaKCPrakasamGBamezaiRNK. DNA methyltransferase1 (DNMT1) isoform3 Methylates Mitochondrial Genome and Modulates Its Biology. Sci Rep (2017) 7:1525. 10.1038/s41598-017-01743-y

85.

BellizziDD’AquilaPScafoneTGiordanoMRisoVRiccioAet alThe Control Region of Mitochondrial DNA Shows an Unusual Cpg and Non-cpg Methylation Pattern. DNA Res (2013) 20:537–47. 10.1093/dnares/dst029

86.

MechtaMIngerslevLRFabreOPicardMBarrèsR. Evidence Suggesting Absence of Mitochondrial DNA Methylation. Front Genet (2017) 8:166. 10.3389/fgene.2017.00166

87.

HaoZWuTCuiXZhuPTanCDouXet alN6-deoxyadenosine Methylation in Mammalian Mitochondrial DNA. Mol Cell (2020) 78:382–95.e8. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.02.018

88.

LiXZhangZLuoXSchrierJYangADWuTP. The Exploration of N6-deoxyadenosine Methylation in Mammalian Genomes. Protein Cell (2021) 12:756–68. 10.1007/s13238-021-00866-3

89.

KohCWQGohYTTohJDWNeoSPNgSBGunaratneJet alSingle-Nucleotide-Resolution Sequencing of Human N 6-methyldeoxyadenosine Reveals strand-asymmetric Clusters Associated with SSBP1 on the Mitochondrial Genome. Nucleic Acids Res (2018) 46:11659–70. 10.1093/nar/gky1104

90.

SharmaNPasalaMSPrakashA. Mitochondrial DNA: Epigenetics and Environment. Environ Mol Mutagen (2019) 60:668–82. 10.1002/em.22319

91.

ZhangFZhangLHuGChenXLiuHLiCet alRectifying METTL4-mediated N 6 -methyladenine Excess in Mitochondrial DNA Alleviates Heart Failure. Circulation (2024) 150:1441–58. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.068358

92.

DostalVChurchillMEA. Cytosine Methylation of Mitochondrial DNA at Cpg Sequences Impacts Transcription Factor A DNA Binding and Transcription. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech (2019) 1862:598–607. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2019.01.006

93.

PatilVCueninCChungFAguileraJRRFernandez-JimenezNRomero-GarmendiaIet alHuman Mitochondrial DNA Is Extensively Methylated in a Non-cpg Context. Nucleic Acids Res (2019) 47:10072–85. 10.1093/nar/gkz762

94.

DouXBoyd-KirkupJDMcDermottJZhangXLiFRongBet alThe strand-biased Mitochondrial DNA Methylome and Its Regulation by DNMT3A. Genome Res (2019) 29:1622–34. 10.1101/gr.234021.117

95.

CaoKLvWWangXDongSLiuXYangTet alHypermethylation of Hepatic Mitochondrial ND6 Provokes Systemic Insulin Resistance. Adv Sci (2021) 8:2004507. 10.1002/advs.202004507

96.

LüthTWasnerKKleinCSchaakeSTseRPereiraSLet alNanopore single-molecule Sequencing for Mitochondrial DNA Methylation Analysis: Investigating parkin-associated Parkinsonism as a Proof of Concept. Front Aging Neurosci (2021) 13:713084. 10.3389/fnagi.2021.713084

97.

YueYRenLZhangCMiaoKTanKYangQet alMitochondrial Genome Undergoes De Novo DNA Methylation that Protects Mtdna Against Oxidative Damage During the peri-implantation Window. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2022) 119:e2201168119. 10.1073/pnas.2201168119

98.

ZhangZHuangQZhaoDLianFLiXQiW. The Impact of Oxidative stress-induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction on Diabetic Microvascular Complications. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2023) 14:1112363. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1112363

99.

MishraMKowluruRA. Epigenetic Modification of Mitochondrial DNA in the Development of Diabetic Retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2015) 56:5133–42. 10.1167/iovs.15-16937

100.

KowluruRA. Retinopathy in a diet-induced Type 2 Diabetic Rat Model and Role of Epigenetic Modifications. Diabetes (2020) 69:689–98. 10.2337/db19-1009

101.

BordoniLSmerilliVNasutiCGabbianelliR. Mitochondrial DNA Methylation and Copy Number Predict Body Composition in a Young Female Population. J Transl Med (2019) 17:399. 10.1186/s12967-019-02150-9

102.

ZhengLDLinarelliLEBrookeJSmithCWallSSGreenawaldMHet alMitochondrial Epigenetic Changes Link to Increased Diabetes Risk and early-stage Prediabetes Indicator. Oxid Med Cell Longev (2016) 2016:5290638–10. 10.1155/2016/5290638

103.

ZhengLDLinarelliLELiuLWallSSGreenawaldMHSeidelRWet alInsulin Resistance Is Associated with Epigenetic and Genetic Regulation of Mitochondrial DNA in Obese Humans. Clin Epigenetics (2015) 7:60. 10.1186/s13148-015-0093-1

104.

AnsteeQMMcPhersonSDayCP. How Big a Problem Is Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease?BMJ (2011) 343:d3897. 10.1136/bmj.d3897

105.

LoombaRAbrahamMUnalpAWilsonLLavineJDooEet alAssociation Between Diabetes, Family History of Diabetes, and Risk of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Fibrosis. Hepatology (2012) 56:943–51. 10.1002/hep.25772

106.

PirolaCJGianottiTFBurgueñoALRey-FunesMLoidlCFMallardiPet alEpigenetic Modification of Liver Mitochondrial DNA Is Associated with Histological Severity of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gut (2013) 62:1356–63. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302962

107.

ShiYZhangHHuangSYinLWangFLuoPet alEpigenetic Regulation in Cardiovascular Disease: Mechanisms and Advances in Clinical Trials. Signal Transduct Target Ther (2022) 7:200. 10.1038/s41392-022-01055-2

108.

WoischnikMMoraesCT. Pattern of Organization of Human Mitochondrial Pseudogenes in the Nuclear Genome. Genome Res (2002) 12:885–93. 10.1101/gr.227202

109.

Milián-GarcíaYHempelCAJankeLAAYoungRGFurukawa-StofferTAmbagalaAet alMitochondrial Genome Sequencing, Mapping, and Assembly Benchmarking for Culicoides Species (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). BMC Genomics (2022) 23:584. 10.1186/s12864-022-08743-x

110.

LiaoP-CBergaminiCFatoRPonLAPallottiF. Isolation of Mitochondria from Cells and Tissues. Methods Cell Biol (2020) 2(155):3–31. 10.1016/bs.mcb.2019.10.002

111.

RepolêsBMGorospeCMTranPNilssonAKWanrooijPH. The Integrity and Assay Performance of Tissue Mitochondrial DNA Is Considerably Affected by Choice of Isolation Method. Mitochondrion (2021) 61:179–87. 10.1016/j.mito.2021.10.005

112.

Quispe-TintayaWWhiteRRPopovVNVijgJMaslovAY. Fast Mitochondrial DNA Isolation from Mammalian Cells for next-generation Sequencing. Biotechniques (2013) 55:133–6. 10.2144/000114077

113.

ChengCFeiZXiaoP. Methods to Improve the Accuracy of next-generation Sequencing. Front Bioeng Biotechnol (2023) 11:982111. 10.3389/fbioe.2023.982111

114.

YuHHahnYYangI. Reference Materials for Calibration of Analytical Biases in Quantification of DNA Methylation. PLoS One (2015) 10:e0137006. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137006

115.

MohammadiMMBaviO. DNA Sequencing: An Overview of Solid-State and Biological Nanopore-based Methods. Biophys Rev (2022) 14:99–110. 10.1007/s12551-021-00857-y

116.

Victoria WangXBladesNDingJSultanaRParmigianiG. Estimation of Sequencing Error Rates in Short Reads. BMC Bioinformatics (2012) 13:185. 10.1186/1471-2105-13-185

117.

HoffKJ. The Effect of Sequencing Errors on Metagenomic Gene Prediction. BMC Genomics (2009) 10:520. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-520

118.

RonchiDGaroneCBordoniAGutierrezRPCalvoSERipoloneMet alNext-Generation Sequencing Reveals DGUOK Mutations in Adult Patients with Mitochondrial DNA Multiple Deletions. Brain (2012) 135:3404–15. 10.1093/brain/aws258

119.

RieberNZapatkaMLasitschkaBJonesDNorthcottPHutterBet alCoverage Bias and Sensitivity of Variant Calling for Four whole-genome Sequencing Technologies. PLoS One (2013) 8:e66621. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066621

120.

van DijkELAugerHJaszczyszynYThermesC. Ten Years of next-generation Sequencing Technology. Trends Genet (2014) 30:418–26. 10.1016/j.tig.2014.07.001

121.

MascherMWuSAmandPSSteinNPolandJ. Application of Genotyping-By-Sequencing on Semiconductor Sequencing Platforms: A Comparison of Genetic and Reference-Based Marker Ordering in Barley. PLoS One (2013) 8:e76925. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076925

122.

GoodwinSMcPhersonJDMcCombieWR. Coming of Age: Ten Years of next-generation Sequencing Technologies. Nat Rev Genet (2016) 17:333–51. 10.1038/nrg.2016.49

123.

DonathXSaint-MartinCDubois-LaforgueDRajasinghamRMifsudFCianguraCet alNext-Generation Sequencing Identifies Monogenic Diabetes in 16% of Patients with Late Adolescence/Adult-Onset Diabetes Selected on a Clinical Basis: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. BMC Med (2019) 17:132. 10.1186/s12916-019-1363-0

124.

DaiQYeCIrkliyenkoIWangYSunH-LGaoYet alUltrafast Bisulfite Sequencing Detection of 5-methylcytosine in DNA and RNA. Nat Biotechnol (2024) 42:1559–70. 10.1038/s41587-023-02034-w

125.

KrehenwinkelHWolfMLimJYRomingerAJSimisonWBGillespieRG. Estimating and Mitigating Amplification Bias in Qualitative and Quantitative Arthropod Metabarcoding. Sci Rep (2017) 7:17668. 10.1038/s41598-017-17333-x

126.

MechtaMIngerslevLRBarrèsR. Methodology for Accurate Detection of Mitochondrial DNA Methylation. J Vis Exp (2018) 135:e57772. 10.3791/57772

127.

DevallMSoanesDMSmithARDempsterELSmithRGBurrageJet alGenome-Wide Characterization of Mitochondrial DNA Methylation in Human Brain. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2022) 13:1059120. 10.3389/fendo.2022.1059120

128.

GuittonRDölleCAlvesGOle-BjørnTNidoGSTzoulisC. Ultra-Deep Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing Reveals a Single Methylation Hotspot in Human Brain Mitochondrial DNA. Epigenetics (2022) 17:906–21. 10.1080/15592294.2022.2045754

129.

AminuddinANgPYLeongC-OChuaEW. Mitochondrial DNA Alterations May Influence the Cisplatin Responsiveness of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Sci Rep (2020) 10:7885. 10.1038/s41598-020-64664-3

130.

BicciICalabreseCGolderZJGomez-DuranAChinneryPF. Oxford Nanopore Sequencing-based Protocol to Detect Cpg Methylation in Human Mitochondrial DNA (2021). 10.1101/2021.02.20.432086

131.

GoldsmithCRodríguez-AguileraJREl-RifaiIJarretier-YusteAHervieuVRaineteauOet alLow Biological Fluctuation of Mitochondrial Cpg and Non-cpg Methylation at the single-molecule Level. Sci Rep (2021) 11:8032. 10.1038/s41598-021-87457-8

132.

BaccarelliAAByunH-M. Platelet Mitochondrial DNA Methylation: A Potential New Marker of Cardiovascular Disease. Clin Epigenetics (2015) 7:44. 10.1186/s13148-015-0078-0

133.

LiuBDuQChenLFuGLiSFuLet alCpg Methylation Patterns of Human Mitochondrial DNA. Sci Rep (2016) 6:23421. 10.1038/srep23421

134.

MposhiACortés-ManceraFHeegsmaJde MeijerVEvan de SluisBSydorSet alMitochondrial DNA Methylation in Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Front Nutr (2023) 10:964337. 10.3389/fnut.2023.964337

135.

SturmÁSharmaHBodnárFAslamMKovácsTNémethÁet alN6-methyladenine Progressively Accumulates in Mitochondrial DNA During Aging. Int J Mol Sci (2023) 24:14858. 10.3390/ijms241914858

136.

RauluseviciuteIDrabløsFRyeMB. DNA Methylation Data by Sequencing: Experimental Approaches and Recommendations for Tools and Pipelines for Data Analysis. Clin Epigenetics (2019) 11:193. 10.1186/s13148-019-0795-x

137.

DelahayeCNicolasJ. Sequencing DNA with Nanopores: Troubles and Biases. PLoS One (2021) 16:e0257521. 10.1371/journal.pone.0257521

138.

TaborHKBerkmanBEHullSCBamshadMJ. Genomics Really Gets Personal: How Exome and Whole Genome Sequencing Challenge the Ethical Framework of Human Genetics Research. Am J Med Genet A (2011) 155:2916–24. 10.1002/ajmg.a.34357

139.

Martinez-MartinNMagnusD. Privacy and Ethical Challenges in next-generation Sequencing. Expert Rev Precis Med Drug Dev (2019) 4:95–104. 10.1080/23808993.2019.1599685

140.

TurnwaldBPGoyerJPBolesDZSilderADelpSLCrumAJ. Learning One’s Genetic Risk Changes Physiology Independent of Actual Genetic Risk. Nat Hum Behav (2018) 3:48–56. 10.1038/s41562-018-0483-4

141.

KnoppersBMZawatiMHSénécalK. Return of Genetic Testing Results in the Era of whole-genome Sequencing. Nat Rev Genet (2015) 16:553–9. 10.1038/nrg3960

142.

SaxenaNTanejaNShomePManiS. Mitochondrial Donation: A Boon or Curse for the Treatment of Incurable Mitochondrial Diseases. J Hum Reprod Sci (2018) 11:3–9. 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_54_17

Summary

Keywords

ethical limitations, haploid, methylation, mitochondrial dysfunction, next-generation sequencing

Citation

Koh MX, Simpson T, Zain SM, Ayub Q, Cheah HL, Pan Y, Cheng SH and Pung Y-F (2025) Mitochondrial DNA Mutations and Epigenetic Regulation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Development. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 82:15375. doi: 10.3389/bjbs.2025.15375

Received

04 August 2025

Revised

07 November 2025

Accepted

17 November 2025

Published

27 November 2025

Volume

82 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Koh, Simpson, Zain, Ayub, Cheah, Pan, Cheng and Pung.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuh-Fen Pung, yuhfen.pung@nottingham.edu.my

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.