Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is the most aggressive breast cancer subtype, characterized by a lack of key hormone receptors in tumor cells. As there are limited treatment options for these patients, it is crucial to understand the underlying mechanisms by which TNBC constantly evolves and evades treatments. In this regard, the pervasive nature of transcription provides a potential reservoir of transcripts, including both coding and noncoding, that TNBC leverages to sustain a proliferative advantage and support tumor growth. TNBC is affected by energy sources such as glucose, which can have a profound impact on gene expression regulation mediated by various molecules, including noncoding RNAs, at the cellular level. In this study, we demonstrate that glucose modulates the gene expression profile mediated by the microRNA-503 host gene (MIR503HG), which has been previously implicated in TNBC. To comprehensively characterize the impact of glucose on MIR503HG-regulated genes and cellular pathways, we sequenced total RNA, performed gene set enrichment analyses, and determined the relation between gene expression and patient outcomes. Analysis of gene subsets specific to various glucose environments identified clinical outcomes for breast cancer patients across different molecular subtypes. Our findings indicate that MIR503HG has potential as a diagnostic marker and may be useful in the clinical management of TNBC.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the leading cancer among women worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2022, 2.3 million women were diagnosed with breast cancer, and there were 685,000 deaths globally [1]. Breast cancer is heterogeneous in nature, with multiple molecular subtypes. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for approximately 15%–20% of all breast carcinomas [2] and is associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes and higher recurrence rates than other subtypes [3]. TNBCs are characterized by the low levels or complete absence of key hormone receptors, particularly estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and an oncogene known as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), which is a target of trastuzumab [4]. The lack of these hormone receptors creates a hazardous scenario for TNBC patients, as the tumors do not respond to hormone-targeting drugs that are typically used in hormone receptor-positive cancer cases. As such, standard treatments for TNBC include surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy [5], with post-treatment recurrence rates around 50% for patients diagnosed in the earlier stages [6]. Chemotherapeutic drugs, such as anthracyclines and taxanes, are commonly used in combination to treat TNBC. Anthracyclines, like doxorubicin and epirubicin, intercalate DNA strands, leading to DNA damage and cell death [7–9]. Taxanes, such as paclitaxel and docetaxel, act by stabilizing microtubules, consequently disrupting mitosis [10]. Even though there are several chemotherapeutics available to treat TNBC, identifying novel therapeutic targets for this complex breast cancer subtype, as well as learning more about its pathology, persists as a critical problem to address [11, 12].

One of the hallmark characteristics of cancer cells is metabolic reprogramming, which enables them to thrive and rapidly proliferate in a nutrient-deficient tumor microenvironment (TME). The Warburg effect describes how cancer cells are able to survive in the TME, as they exhibit high rates of aerobic glycolysis, where the cells convert glucose to lactate regardless of the presence or absence of oxygen [13, 14]. The rewiring of their metabolic network enables the cells to meet their bioenergetic demands and promote oncogenic pathways, leading to their proliferation and metastasis [15]. Although this phenomenon is seen across a wide array of cancers, studies have shown that TNBC is highly glycolytic compared to other molecular subtypes of breast carcinomas, which might contribute to its aggressiveness and poor outcomes [16]. Recent studies have classified TNBCs into multiple subtypes based on their metabolic phenotype [17], meaning each subtype must be treated uniquely. This predicament underscores the need to develop alternative therapeutic strategies that target TNBC across diverse environmental conditions.

Several studies have reported that long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) play an integral role in cancer cell metabolism [18–20]. LncRNAs are non-coding RNAs that have a length of 200 nucleotides or greater and play diverse roles in the regulation of gene transcription, translation, and epigenetic modification [21]. Notably, lncRNAs are able to modulate gene regulation via both cis-acting and trans-acting mechanisms, which sets them apart from other non-coding RNAs such as small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) [22]. In recent years, numerous lncRNAs have been associated with various aspects of TNBC, ranging from its pathogenesis to therapy resistance and prognosis [23], with lncRNAs exhibiting either oncogenic or tumor-suppressive characteristics [24, 25]. The involvement of dysregulated lncRNAs in the development and progression of TNBC is an area that requires further study, due to the complexity involved in characterizing lncRNAs as well as the heterogeneous nature of TNBCs.

Although the roles of lncRNAs in TNBC are an area that has been studied, there are still many lncRNAs whose mechanisms have not been fully characterized. In this study, we investigated a specific lncRNA, microRNA-503 host gene (MIR503HG), whose original roles were thought to be primarily angiogenic in nature [26]. Later studies identified MIR503HG as being highly expressed in reproductive tissues [27], and most recently, it has been identified as an oncogene in prostate cancer [28] and as a regulator of cell differentiation and insulin production in stem cell-derived pancreatic progenitors [29]. Other studies have shown that the overexpression of MIR503HG can impair epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) properties, acting as a tumor suppressor lncRNA in diseases such as ovarian cancer [30]. Furthermore, MIR503HG has been implicated in TNBC, in which it inhibits cell proliferation [31]. However, in the context of glucose involvement in cancer, it will be crucial to determine whether it affects MIR503HG-dependent gene regulation. Additionally, the role of glucose in modulating MIR503HG-dependent gene regulation in TNBC remains an unexplored area. Hence, the objective of this study was to identify the effects of glucose on MIR503HG-mediated gene expression in TNBC cells and assess its possible clinical implications. To achieve this, we treated TNBC cells engineered to overexpress MIR503HG with varying amounts of glucose. Subsequently, we conducted total RNA-sequencing to evaluate the impact of glucose on genes regulated by MIR503HG. Our RNA-seq analysis of this data has revealed that MIR503HG-regulated genes were modulated by glucose, altering the expression profiles of TNBC cells. Overall, our analyses have unveiled interesting biological aspects of glucose and MIR503HG interaction in TNBC. These findings could potentially be applied in the clinical setting to inform the development of novel therapeutic approaches.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Cell Culture Conditions

MDA-MB-157 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and regularly cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (5 g/L glucose, Sigma-Aldrich, D6429). The media was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, 26140079) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, 15140-122), and cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. For induction of MIR503HG or GFP with doxycycline (Dox, Sigma Aldrich, D9891), the cells were treated with 250 ng/mL of Dox for the indicated times before collection. For glucose treatments, cells were incubated in low-glucose DMEM media (1 g/L glucose, Sigma-Aldrich, D6046) for 48 h, before being treated with the experimental glucose concentration (1, 5, or 15 g/L glucose) and co-treated with Dox for 4 h.

Dox-inducible Ectopic Expression in Cell Lines

Lentiviruses were generated by transfecting HEK293T cells (ATCC, CRL-3216) with pInducer20 [32] containing MIR503HG or GFP, along with pMD2.G, psPAX2 plasmids using the Lipofectamine 3000 kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, L3000015) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Medium from transfected 293T cells was collected and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter to transduce MDA-MB-157 cells, and polybrene (0.5 μg/mL) was added. Stably transduced cells were selected under drug selection by Geneticin™ (G418, Gibco, 11-811-031) at 1 μg/mL and were used for Dox-induced ectopic expression of MIR503HG and GFP to perform a variety of experiments described herein.

Total RNA Isolation, RNA-Seq Library Preparation, and Sequencing

Cells expressing inducible MIR503HG or GFP were seeded in six-well plates and treated with 250 ng/mL Dox and media with the indicated glucose concentrations for 4 h. The total RNA was isolated using EZ-10 DNAway RNA Mini-Preps Kit (Bio Basic, Canada). Agilent Technologies 4200 TapeStation was used to analyze RNA integrity of the preparation, and Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific, USA) was used to conduct RNA quantification. Only isolated RNA samples with >9 RIN (RNA Integrity Number) were utilized for RNA-seq library preparation. RNA-seq libraries for total RNA-sequencing were prepared and sequenced at Novogene Corporation (Sacramento, CA). Briefly, ribosomal RNA was removed from the total RNA and then precipitated using ethanol. After fragmentation, the cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers, followed by the addition of a second-strand synthesis buffer (Illumina), dNTPs, RNase H, and DNA polymerase I to initiate the second-strand synthesis. Next, terminal repair, A-tailing, and sequencing adaptor ligation steps were carried out. Finally, the double-stranded cDNA library was completed through size selection and PCR enrichment. The libraries then went through QC checks, which include Qubit 2.0, Agilent 2100, and real-time PCR. Finally, the quantified libraries were pooled according to the concentration and data amount required and fed into Illumina sequencers (NovaSeq X Plus).

Transcriptomic Data

The transcriptomic data for this study were submitted to NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through NCBI-GEO-GSE297214. This dataset represents RNA-seq-based gene expression in the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-157, which includes samples of G1, G5, and G15 glucose treatments for cells overexpressing MIR503HG or GFP.

Transcriptome Assembly and Differential Gene Expression

In this study, the raw reads (fastq files) from total RNA-sequencing were uploaded to Genialis™ Expressions 3.0 [33] and processed using the General RNA-seq pipeline (featureCounts). Reads were trimmed using BBDuk (BBMap 37.90), followed by alignment to the human genome (hg38) with annotation from Ensembl release version 109 (February 2023) using STAR aligner (v2.7.10b) [34]. BAM files were then sorted and indexed using Samtools (v1.14) [35]. Read counts were quantified using featureCounts (1.6.3) [36], with reference annotation from Ensembl version 109. Normalization of expression values was calculated using rnanorm (1.3.1). The DESeq2 tool was used for count normalization and differential gene expression analyses. Filtering criteria for differentially expressed genes were set by applying a p-value (≤0.05).

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

Utilizing the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) [37], Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) version 4.4.0 was conducted to examine the relationship among top DEGs to specific processes and mechanisms. Top 20 gene sets (gene ontologies) with FDR q-value less than 0.05 for gene ontology (GO), KEGG, Hallmark, and CGP were generated for up- and downregulated genes. Genes were ranked by log2 Fold Change value, and the top 500 were used as the input gene set for the GSEA.

Kaplan-Meier and Gene Expression Analyses of Breast Tumor Samples

To evaluate the prognostic value of identified differentially expressed genes specific to glucose treatment, we explored the expression of merged gene sets across breast tumor tissues. The Kaplan-Meier plots estimating overall survival (OS), distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS), and relapse-free survival (RFS) in three quantiles over 10 years were generated utilizing the Gene Expression-Based Outcome for Breast Cancer Online (GOBO) tool [38]. Genes were ranked by log2 Fold Change value, and the top 500 up- and downregulated genes were used as the input gene sets for the GOBO. Boxplots of merged gene sets across molecular breast tumor subgroups was also attained using the GOBO tool, using the same gene sets. Each box depicts the combined expression score within a subgroup, with the dotted line indicating the overall median expression across all samples.

Results

Glucose Regulates MIR503HG-Dependent Genes in a Dose-Dependent Manner

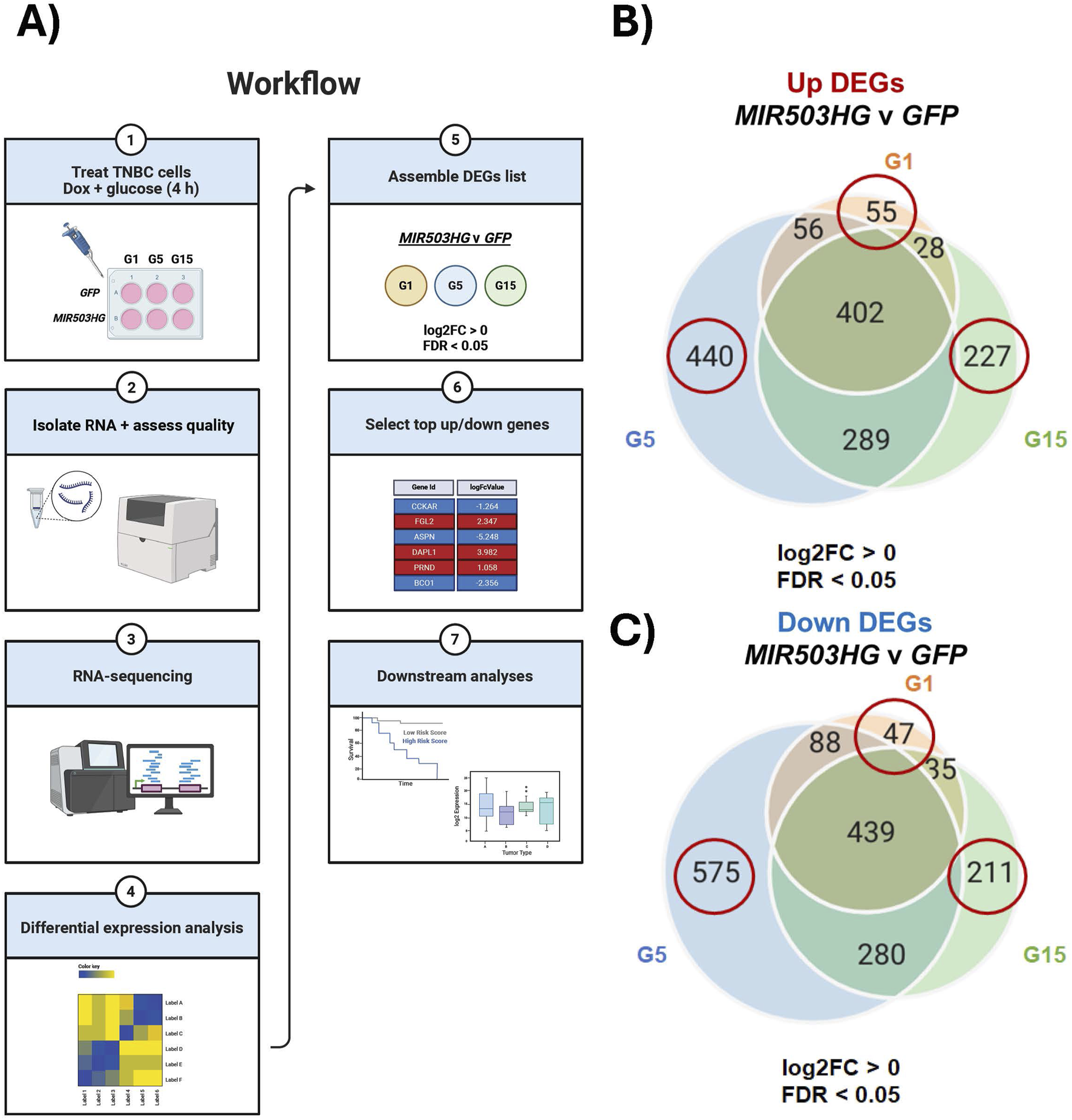

To investigate the role of glucose in MIR503HG-dependent gene expression, we conducted RNA-sequencing to identify condition-specific gene sets. Dox-inducible MDA-MB-157 cells were generated to overexpress MIR503HG or GFP. We resorted to ectopically expressing MIR503HG (mature and processed RNA), enabling us to identify MIR503HG-regulated gene sets independently of miRNAs. These cells were treated with different glucose concentrations 1 g/L, 5 g/L, and 15 g/L (G1, G5, G15, respectively) for 4 h, while co-treated with doxycycline to induce overexpression of MIR503HG or GFP (Figure 1A). At 4 h, the cells were collected, and total RNA was isolated (Figure 1A). Differential expression analyses of RNA-sequencing data identified distinct up- and downregulated gene sets for MIR503HG-regulated genes compared to GFP (Figures 1A,B). The condition-specific differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were utilized to conduct downstream analyses, as shown in Figure 1A, highlighting the biological and clinical significance of glucose on these genes. Figures 1B,C show Venn diagrams for up- and downregulated gene sets, the circled ones of which were used for all subsequent analyses. It was noticed that there were fewer up- and downregulated genes specific to G1, 55 and 47 respectively, compared to the gene sets for G5 and G15 (Figures 1B,C; Supplementary Tables S1–S3).

FIGURE 1

Experimental workflow and RNA-seq expression of differentially expressed genes. The workflow illustrates the experimental design and downstream processes that utilized condition-specific genes. (A) Flow chart of experimental design using circled gene sets from Venn diagrams for (B) upregulated and (C) downregulated genes. Samples include: G1, G5, and G15 for MIR503HG and GFP. Created with BioRender.com. G1, G5, G15: 1, 5, or 15 g/L of glucose. GFP: Green Fluorescent Protein. DEGs: Differentially Expressed Genes; FDR: False Discovery Change; TNBC: Triple Negative Breast Cancer.

Specific Glucose Dose Affects a Distinct Set of MIR503HG-Regulated Genes Predicting Clinical Outcomes Across Various Breast Cancer Subtypes

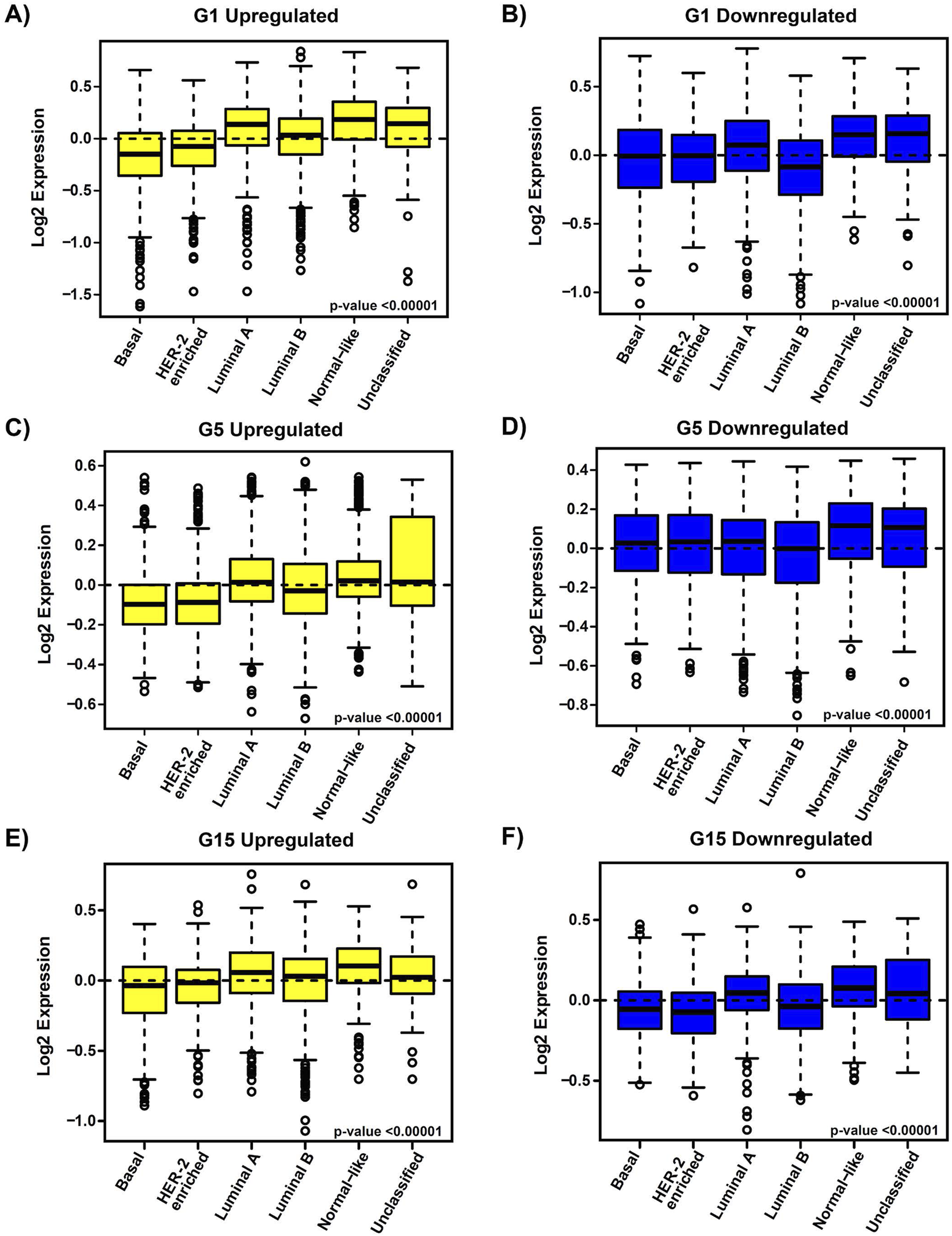

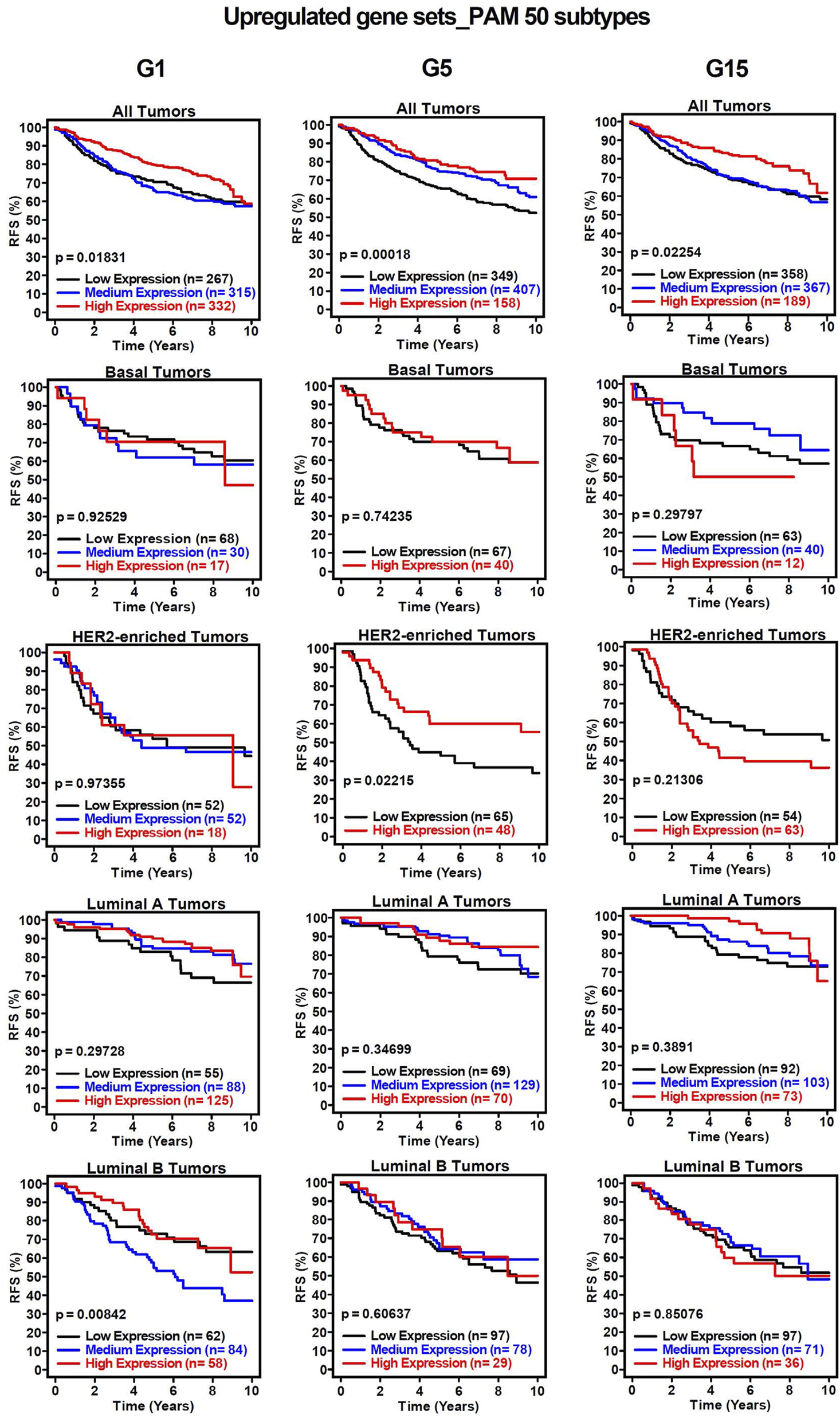

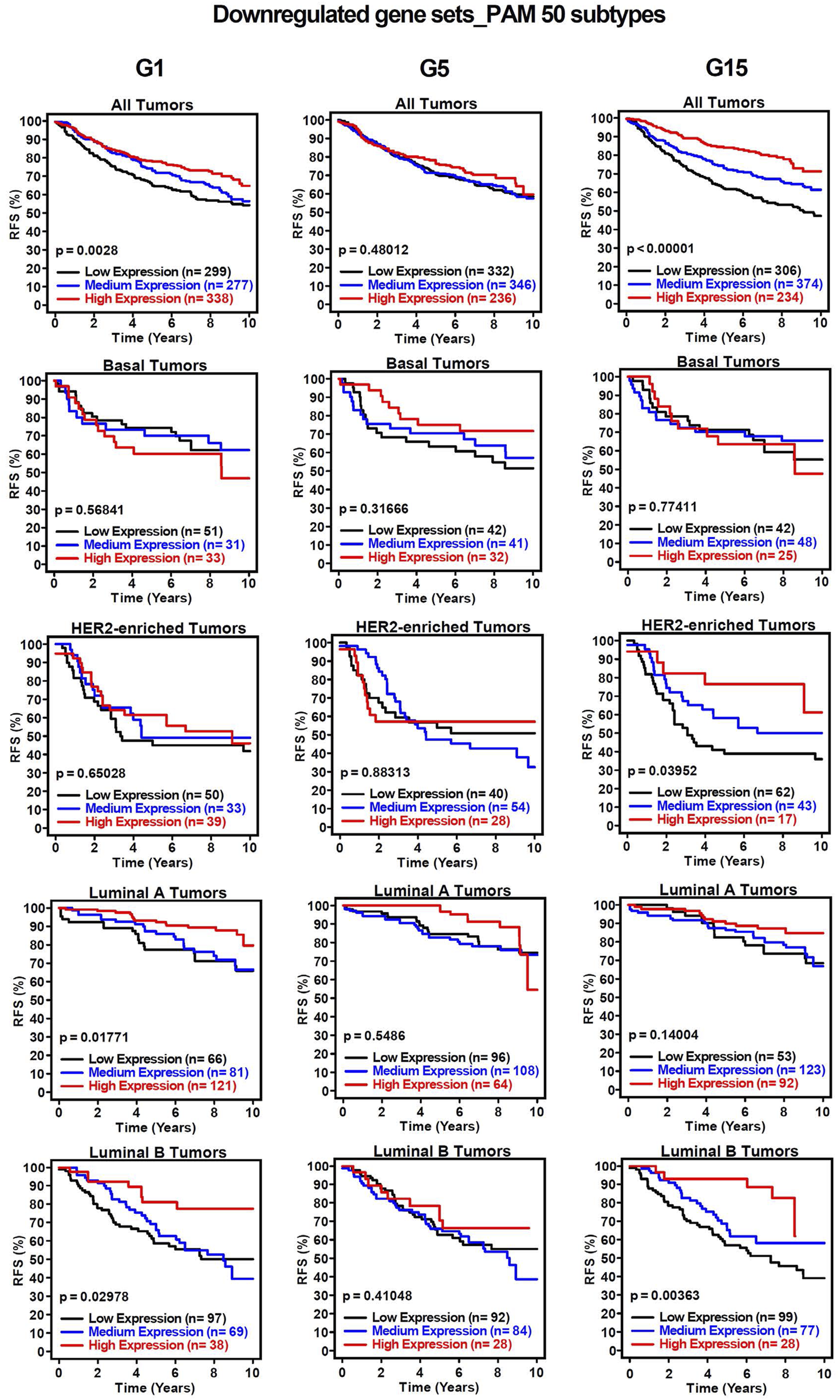

To assess the clinical significance of the identified MIR503HG-regulated gene sets affected by specific glucose doses, an 1881-sample breast cancer dataset from Gene Expression-Based Outcome for Breast Cancer Online (GOBO) was used. Boxplots were generated to show expression levels of condition-specific gene sets across PAM50 tumors, indicating significant differences among molecular subtypes of breast cancer (Figure 2). Most markedly, the expression levels of G1 and G5 upregulated genes showed attenuation in basal and HER2-enriched tumors, when compared to G15 (Figures 2A,C,E). It was observed that basal tumors displayed similar expression levels to those observed in our condition-specific downregulated in vitro analysis (Figures 2B,D,F). Additionally, relapse-free survival (RFS) among molecular breast cancer subtypes was examined using the same condition-specific gene sets used previously. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis indicated varying RFS with increased expression of these genes, however, high expression of these gene sets was significantly associated with better RFS rates in All Tumors for G1, G5 and G15 (Figure 3). Similarly, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was conducted on condition-specific downregulated gene sets, showing a significant correlation between low gene expression and low RFS rates for G1 and G15, specifically, for All Tumors (Figure 4). Overall survival (OS) and distance metastasis-free survival (DMFS) were also analyzed, however, there was a wider variation of correlation among tumor types and gene set expression levels (Supplementary Figures S1–S4). Together, these findings demonstrate that glucose concentrations exert distinct regulatory effects on MIR503HG-regulated genes across breast tumor subtypes, with significant implications for predicting clinical outcomes in breast cancer patients.

FIGURE 2

Expression profiles of condition-specific genes’ signature in correlation with breast cancer molecular subtypes in patient tumor samples. Gene signature expression levels according to breast cancer molecular subtype for all tumors, merged gene set, for PAM50 subtypes. Boxplots for (A) G1 upregulated, (B) G1 downregulated, (C) G5 upregulated, (D) G5 downregulated, (E) G15 upregulated, and (F) G15 downregulated gene expression signatures for the following tumor subtypes: Basal (n = 304), HER2-enriched (n = 240), Luminal A (n = 465), Luminal B (n = 471), Normal-like (n = 304) and Unclassified (n = 97). Observed differences are significant by an ANOVA comparison of the means (p-value <0.00001). The dotted line acts as a reference for comparing gene expression levels across different subgroups. G1, G5, G15: 1, 5, or 15 g/L of glucose; HER2: Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2.

FIGURE 3

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for breast cancer subtypes based on upregulated gene signatures shows relapse-free survival rates. Analysis of relapse-free survival rates (RFS) using condition-specific upregulated gene expression signatures. Low expression (black line), medium expression (blue line), and high expression (red line). G1, G5, G15: 1, 5, or 15 g/L of glucose; HER2: Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2.

FIGURE 4

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for breast cancer subtypes based on downregulated gene signatures shows relapse-free survival rates. Analysis of relapse-free survival rates (RFS) using condition-specific downregulated gene expression signatures. Low expression (black line), medium expression (blue line), and high expression (red line). G1, G5, G15: 1, 5, or 15 g/L of glucose; HER2: Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2.

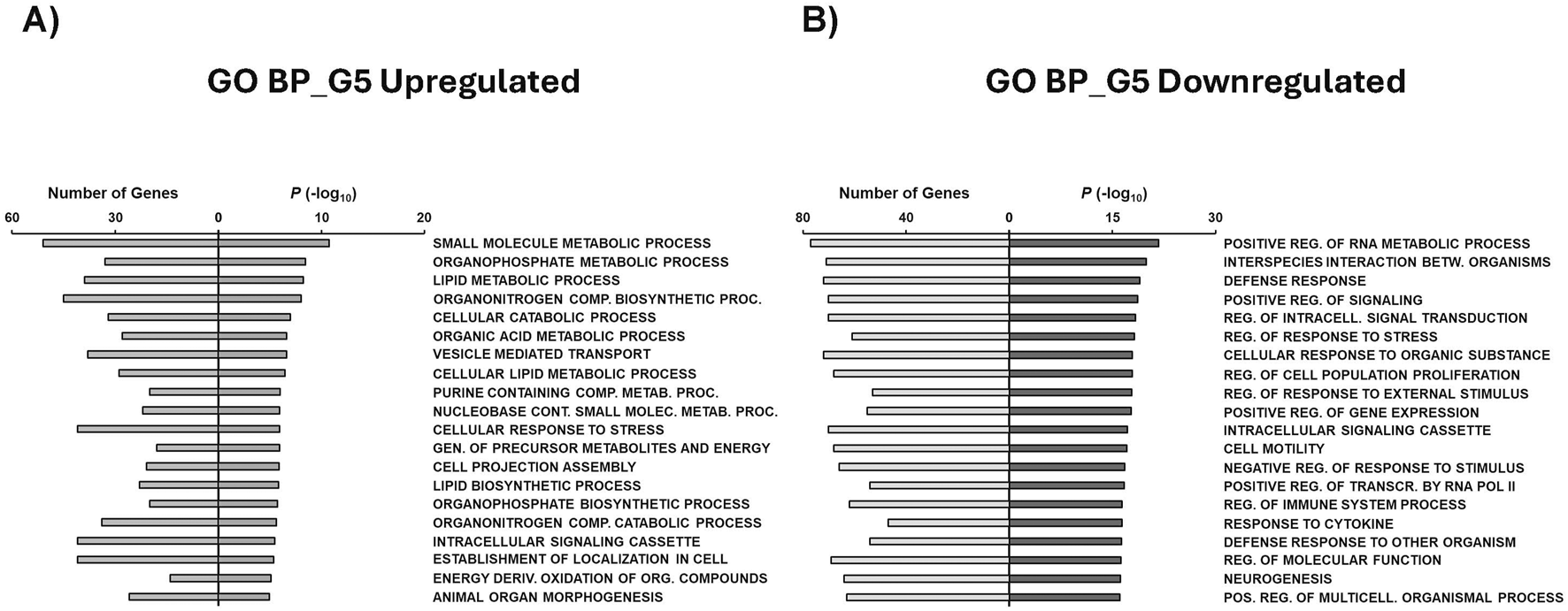

Biological Impact of Glucose-Driven MIR503HG-Regulated Genes

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was conducted to assess the biological impact of each glucose condition on MIR503HG-regulated gene sets. To do this, the previously mentioned condition-specific gene sets were used to derive the top 20 gene ontology (GO) terms, KEGG pathways, Hallmark annotations, and chemical and genetic perturbations (CGP) for each condition, giving insight as to what processes these top up- and downregulated genes are associated with (Figures 5–9; Supplementary Tables S4–S14). Biological processes (BP) for genes upregulated in G5 were mainly involved in metabolic processes relating to small molecules, organophosphates, lipids, cellular catabolic processes, and organic acids (Figure 5A). On the other hand, top BP categories for G5 downregulated genes pertained to regulation of RNA metabolism, signaling, cell proliferation, gene expression, and transcription (Figure 5B). BP for G15 downregulated genes found similar categories to G5 downregulated categories, such as regulation of cell proliferation and signaling, with differences such as proteolysis and phosphorylation observed (Supplementary Figure S5).

FIGURE 5

GSEA shows associated functions of condition-specific genes for Biological Processes. Analysis of condition-specific gene sets for biological processes (BP) in cells exposed to G5 condition. (A) G5 upregulated and (B) G5 downregulated. G5: 5 g/L of glucose; Comp: Compound; Proc: Processes; Metab: Metabolic; Cont: Containing; Molec: Molecule; Gen: Generation; Deriv: Derived; Org: Organic; Reg: Regulation; Betw: Between; Transcr: Transcription; Pos: Positive.

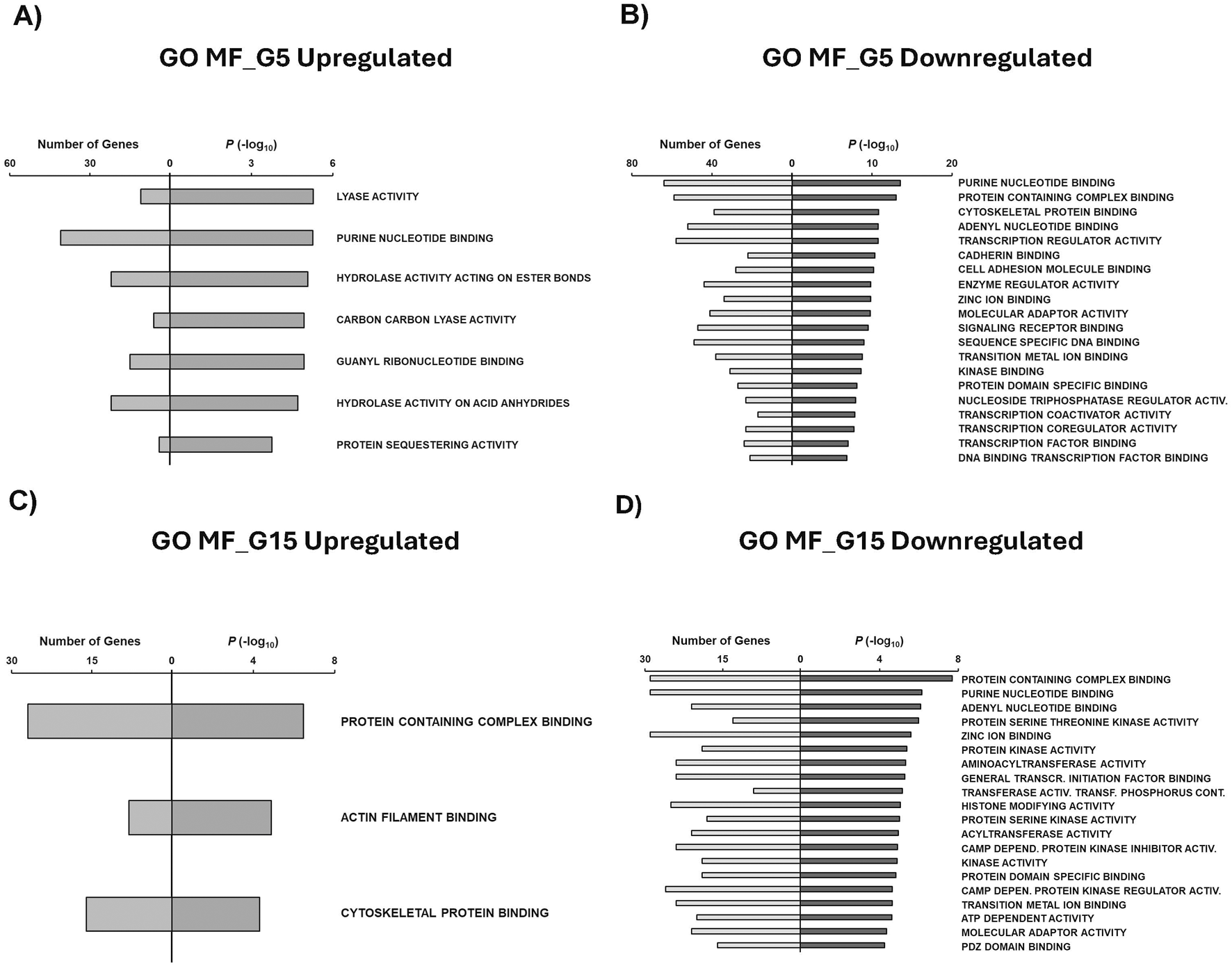

Molecular functions (MF) were then obtained to identify molecular roles associated with condition-specific gene sets. Main MF GO terms associated with G5 upregulated genes include lyase activity, purine nucleotide binding, hydrolase activity acting on ester bonds, carbon carbon lyase activity, and guanyl ribonucleotide binding (Figure 6A). Downregulated genes exposed to the G5 condition revealed MF related to purine nucleotide binding, cadherin binding, signaling receptor binding, kinase binding, and transcription factor binding (Figure 6B). Our study found that G15 upregulated genes were primarily associated with MF protein containing complex binding, actin filament binding, and cytoskeletal protein binding (Figure 6C). G15-specific downregulated genes were found to be related to protein-containing complex, protein kinase activity, histone modifying activity, ATP-dependent activity, and PDZ domain binding (Figure 6D).

FIGURE 6

GSEA shows associated functions of condition-specific genes for Molecular Functions. Analysis of condition-specific gene sets for molecular functions (MF) in cells exposed to G5 and G15 conditions. (A) G5 upregulated, (B) G5 downregulated, (C) G15 upregulated, and (D) G15 downregulated. G5, G15: 5, or 15 g/L of glucose; Activ: Activity; Transcr: Transcription; Activ: Activity; Transf: Transferring; Depend: Dependent.

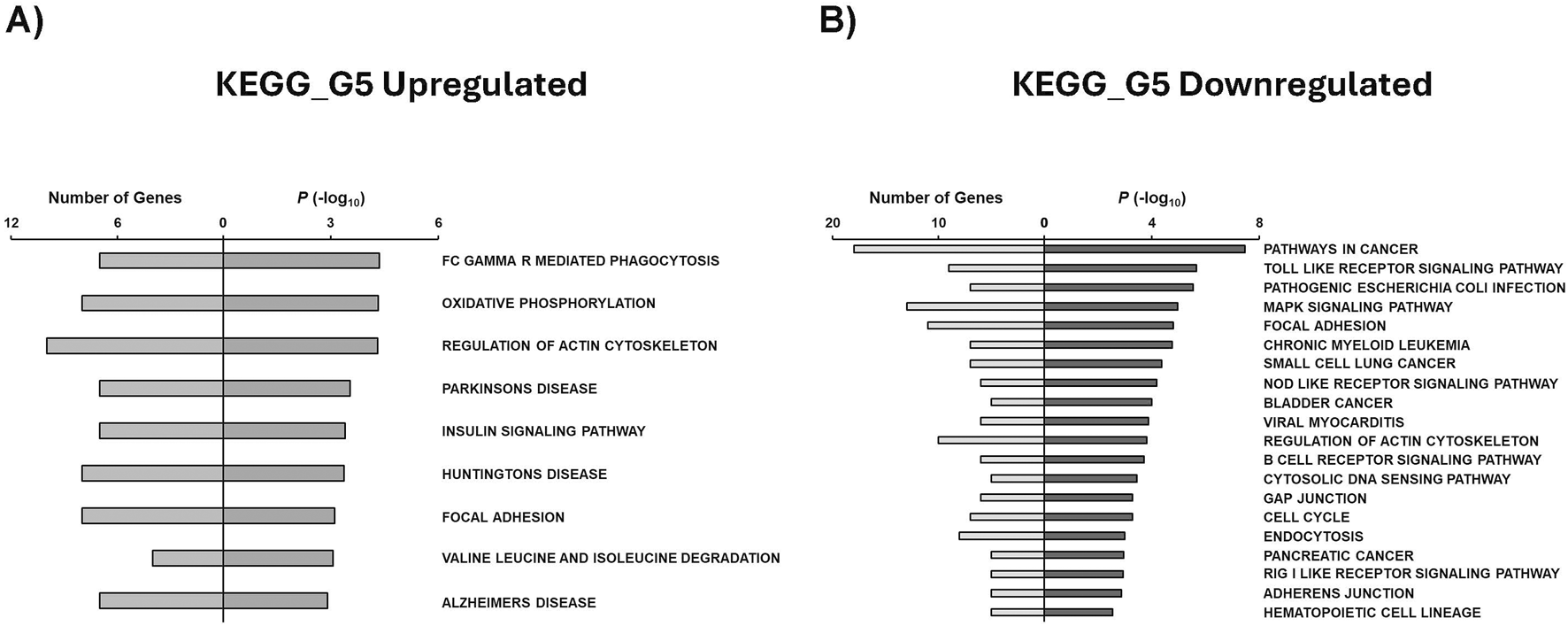

Similarly, we utilized GSEA to identify KEGG pathways associated with condition-specific gene sets. G5 upregulated genes were observed to be related to Fc gamma R mediated phagocytosis, oxidative phosphorylation, regulation of actin cytoskeleton, insulin signaling pathway, and focal adhesion (Figure 7A). It is also interesting to note that genes related to neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, and Alzheimer’s diseases were enriched in the G5 condition. Our study revealed that several KEGG pathways associated with cancer were downregulated in G5, including pathways related to cancer, chronic myeloid leukemia, small cell lung cancer, bladder cancer, and pancreatic cancer (Figure 7B).

FIGURE 7

GSEA shows associated functions of condition-specific genes for KEGG pathways. Analysis of condition-specific gene sets for KEGG pathways in cells exposed to G5 condition. (A) G5 upregulated and (B) G5 downregulated. G5: 5 g/L of glucose; FC: Fragment Crystallizable; R: Receptor.

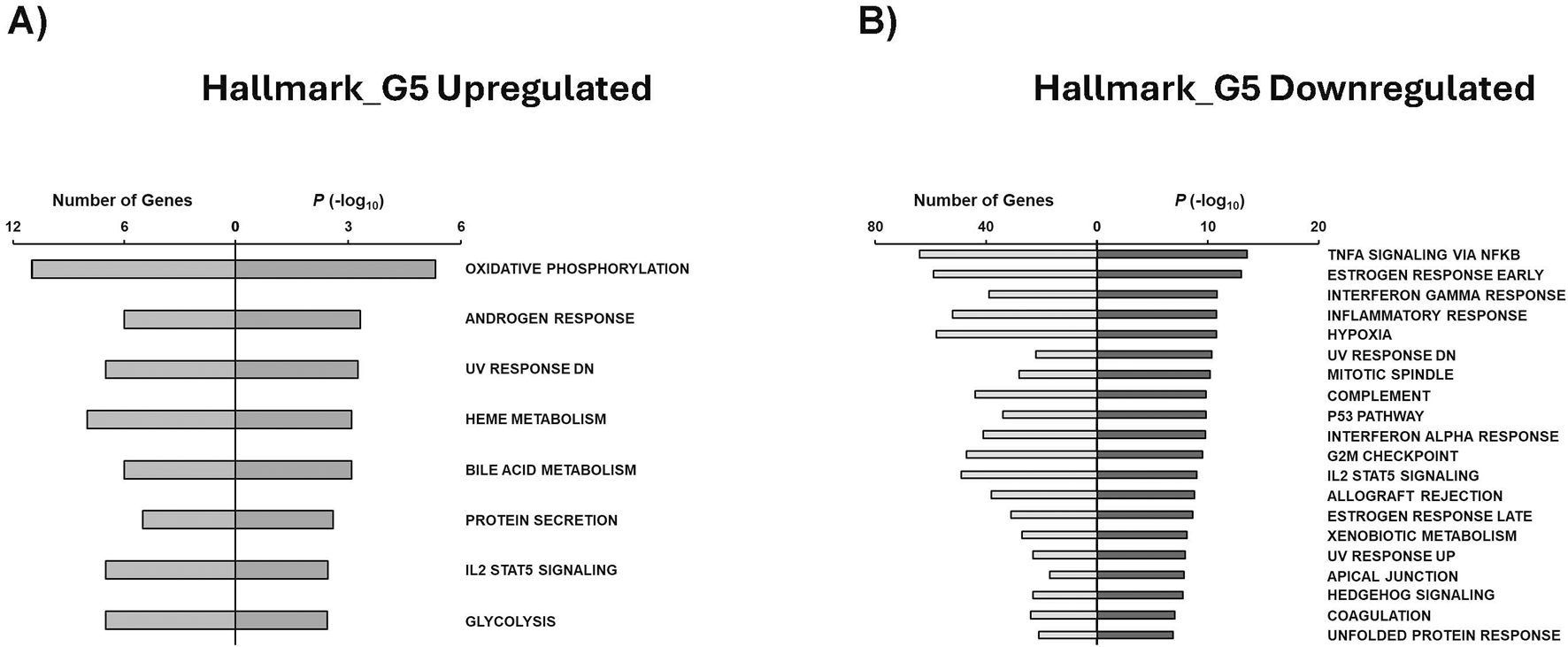

Hallmark annotations were also generated for this study. Upregulated genes in G5 were found to be associated mainly with oxidative phosphorylation, androgen response, heme metabolism, bole acid metabolism, and glycolysis (Figure 8A). On the other hand, G5 downregulated Hallmark annotations were related to TNFa signaling via NFKb, estrogen response, inflammatory response, hypoxia, and P53 pathway (Figure 8B). Interestingly, G1 upregulated gene sets were associated with IL2 STAT5 signaling and adipogenesis (Supplementary Figure S6A), while G15 upregulated genes were related to IL6 JAK STAT3 signaling, glycolysis, and myogenesis (Supplementary Figure S6B).

FIGURE 8

GSEA shows associated functions of condition-specific genes for Hallmark annotations. Analysis of condition-specific gene sets for Hallmark annotations in cells exposed to G5 condition. (A) G5 upregulated and (B) G5 downregulated. G5: 5 g/L of glucose.

Additionally, our GSEA analysis included investigating chemical and genetic perturbations (CGP). Downregulated genes in G1 condition were mainly associated with ovarian cancer tumors and xenografts down (dn), ELAVL1 targets up, liver cancer ciprofibrate up, liver cancer E2F1 up, liver cancer ACOX1 up, and SATB1 targets dn (Supplementary Figure S7). Top CGP related to G5 upregulated genes include Alzheimer’s disease dn, liver cancer up, chronic myelogenous leukemia up, ESR1 targets up, and apoptosis by doxorubicin dn (Figure 9A). Downregulated G5 genes were primarily associated with bronchial epithelial cells influenza A NS1 up, Alzheimer’s disease up, apoptosis by doxorubicin up, ovarian cancer survival suboptimal debulking, and metabolic syndrome (Figure 9B). CGP related to G15 upregulated genes were mainly associated with brain HCP with H3K4me3 and H3K27me3, nasopharyngeal carcinoma dn, adrenocortical tumor dn, endocrine therapy resistance 4, and neuroblastoma copy number up (Figure 9C). Finally, our study showed that genes related to photodynamic therapy stress up, serum response dn, thyroid carcinoma anaplastic up, EZH2 targets up, and Nanog targets CGP were downregulated in the G15 condition (Figure 9D).

FIGURE 9

GSEA shows associated functions of condition-specific genes for CGP. Analysis of condition-specific gene sets for chemical and genetic perturbations (CGP) in cells exposed to G5 and G15 conditions. (A) G5 upregulated, (B) G5 downregulated, (C) G15 upregulated, and (D) G15 downregulated. G5, G15: 5, or 15 g/L of glucose; DN: Down; VS: Versus; UVC: Ultraviolet light; ESR1: Estrogen Receptor alpha; CORR: Correlation; EPITHEL: Epithelial; TNF: Tumor Necrosis Factor; RESPIR: Respiratory; INF: Infection; DEBULK: Debulking; CORR: Correlation; NCP: Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma; HCP: High CpG-density promoters; ICP: Intermediate-CpG-density promoters; PCC: Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient.

Discussion

The treatment of TNBC is challenging due to the lack of tumor-specific targets [39]. Chemotherapy, supplemented with surgery, is the typical treatment strategy for TNBC patients [40], though high recurrence rates are still observed after these standard treatment therapies are administered [41]. Several studies have investigated the relationship between glucose and long non-coding RNAs, specifically in breast cancer [42, 43]. The rewiring of metabolic networks in the tumor microenvironment is a highly valuable characteristic among aggressive cancers. It is now known that there are multiple metabolic phenotypes within the TNBC molecular subtype [17], which makes the development of novel treatments a more challenging yet extremely necessary task.

Select lncRNAs, such as MIR210HG and HANR, have been recognized as modulators of glucose metabolism in TNBC [44, 45]. Additionally, a recent study has explored creating a prognostic risk model based on glucose metabolism-related lncRNAs [43], paving the way for the creation of potential novel therapeutic targets. It is interesting to note that MIR503HG has displayed involvement in glucose-related pathologies such as diabetic nephropathy (DN). A study published in 2020 by Cao and Fan showed MIR503HG and miR-503-5p expression in human proximal tubular epithelial (HK-2) renal cells was upregulated in high glucose conditions, indirectly promoting apoptosis by suppressing anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 [46]. Their findings suggest that this regulatory axis could serve as a potential therapeutic target for diabetic nephropathy. Even though some of the functions of lncRNA MIR503HG in TNBC have been identified [31, 47, 48], the transcriptomic effects of glucose on MIR503HG-regulated genes are still largely unknown. This prompted us to analyze the associated functions of differentially expressed MIR503HG-regulated genes across diverse glucose conditions. One interesting observation in our study is that the condition-specific gene set size for G1 was recognizably smaller than that of G5 and G15, suggesting that there are more shared genes that are differentially regulated in the G1 condition and that glucose affects a very specific MIR503HG-regulated gene set at higher concentrations. Through our analysis of breast cancer patient samples using the GOBO database, we observed that the condition-specific genes showed clinical significance in the correlation between gene expression and relapse-free survival. This indicates that these gene sets could be utilized as prognostic markers to predict patient outcomes. Interestingly, genes regulated by MIR503HG are associated with less aggressive breast cancer subtypes, such as Luminal A. Except under the G15 condition, expression levels in Basal-like and HER2-enriched tumors were higher for downregulated genes compared to upregulated genes (Figure 2). This could be explained by studies showing that MIR503HG functions as a tumor suppressor in ovarian and bladder cancers [30, 49]. Furthermore, this could account for the lack of significant differences in RFS in basal cancer type under different glucose conditions (Figures 3, 4), as the regulated gene sets may be specific to less aggressive cancer subtypes.

During the process of assessing key pathways associated with the identified condition-specific genes, it was noted that many of the regulated genes have neurological functions, as diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s were enriched in the G5 condition. It is noteworthy to mention that recent studies have highlighted the fact that basal-type breast cancers disrupt the blood-brain barrier (BBB) during their metastasis to the brain [50], and that glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) is specifically localized to the BBB [51]. Furthermore, our GSEA analysis of condition-specific gene set revealed associations within the ‘chemical and genetic perturbations’ category, revealed including links to Alzheimer’s disease (G5-upregulated; G5 and G15-downregulated), chromatin modification in brain high-CpG-density promoters (HCPs) (G15-upregulated), and neuroblastoma copy number (G15-upregulated). This correlation requires further in-depth research, as it is an initial investigation of our data.

Furthermore, our study observed key differences in biological function among differentially regulated genes. Genes upregulated in the G5 condition were primarily involved in metabolic processes, while G5-specific downregulated genes were primarily associated with the regulation of gene expression and transcription. This is particularly interesting when compared to the processes related to G15-specific downregulated genes, as the change in dose seemed to not have a profound effect on gene modulation, as processes such as regulation of cell proliferation and signaling were still impacted. More studies are needed, however, as the low gene number between G1-specific and G5-specific groups hindered the ability to conduct further analyses on this comparison.

In conclusion, the differentially expressed MIR503HG-regulated genes in various glucose conditions can be utilized to generate diagnostic and prognostic methods for TNBC. Further studies focusing on specific genes will provide additional data for the development of such tools in the future.

Summary Table

What Is Known About This Subject

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes and higher recurrence rates than other subtypes.

Recent studies have classified TNBCs into multiple subtypes based on their metabolic phenotype, meaning each subtype must be treated uniquely.

LncRNA MIR503HG has been implicated in TNBC, in which it inhibits cell proliferation.

What This Paper Adds

Glucose regulates MIR503HG-dependent genes in a dose-dependent manner.

A distinct set of MIR503HG-regulated genes modulated by glucose predicts clinical outcomes across various breast cancer subtypes.

The crosstalk between glucose and MIR503HG in TNBC uncovered novel biological aspects.

This work represents an advance in biomedical science because it reveals that glucose affects genes regulated by noncoding RNAs, specifically MIR503HG, suggesting their potential use as therapeutic targets in treating TNBC.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Ethical approval was not required for the studies on animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, SG; data curation, investigation, methodology, software, VR and KR; writing – original draft preparation, VR and SG; writing – review and editing, VR, BY, KR, MS, RC, ER, and SG; supervision, SG; project administration, SG; funding acquisition, SG. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a first-time faculty recruitment award from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT; RR170020) and the American Cancer Society (RSG-22-170-01-RMC) grant. SG is partly supported by the NIH 1RO1AI175837-01, Lizanell and Colbert Coldwell Foundation, The Edward N. and Margaret G. Marsh Foundation, and CPRIT-TREC (RP230420).

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the SG lab for their helpful comments. SG is a CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research. Figure 1 was Created with BioRender.com.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/bjbs.2025.15206/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

WHO. Global Breast Cancer Initiative Implementation Framework. Assessing, Strengthening and Scaling up Services for the Early Detection and Management of Breast Cancer. (2023).

2.

Garrido-CastroACLinNUPolyakK. Insights into Molecular Classifications of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Improving Patient Selection for Treatment. Cancer Discov (2019) 9(2):176–98. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1177

3.

MacDonaldINixonNAKhanOF. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Review of Current Curative Intent Therapies. Curr Oncol (2022) 29(7):4768–78. 10.3390/curroncol29070378

4.

BrentonJDCareyLAAhmedAACaldasC. Molecular Classification and Molecular Forecasting of Breast Cancer: Ready for Clinical Application?J Clin Oncol (2005) 23(29):7350–60. 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3845

5.

ObidiroOBattogtokhGAkalaEO. Triple Negative Breast Cancer Treatment Options and Limitations: Future Outlook. Pharmaceutics (2023) 15(7):1796. 10.3390/pharmaceutics15071796

6.

CostaRLBGradisharWJ. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Current Practice and Future Directions. J Oncol Pract (2017) 13(5):301–3. 10.1200/JOP.2017.023333

7.

YadavBSSharmaSCChananaPJhambS. Systemic Treatment Strategies for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. World J Clin Oncol (2014) 5(2):125–33. 10.5306/wjco.v5.i2.125

8.

PloskerGLFauldsD. Epirubicin. A Review of Its Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Properties, and Therapeutic Use in Cancer Chemotherapy. Drugs (1993) 45(5):788–856. 10.2165/00003495-199345050-00011

9.

GeisbergCASawyerDB. Mechanisms of Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity and Strategies to Decrease Cardiac Damage. Curr Hypertens Rep (2010) 12(6):404–10. 10.1007/s11906-010-0146-y

10.

ChouCWHuangYMChangYJHuangCYHungCS. Identified the Novel Resistant Biomarkers for Taxane-Based Therapy for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Int J Med Sci (2021) 18(12):2521–31. 10.7150/ijms.59177

11.

Leon-FerreRAGoetzMP. Advances in Systemic Therapies for Triple Negative Breast Cancer. BMJ (2023) 381:e071674. 10.1136/bmj-2022-071674

12.

KumarHGuptaNVJainRMadhunapantulaSVBabuCSKesharwaniSSet alA Review of Biological Targets and Therapeutic Approaches in the Management of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J Adv Res (2023) 54:271–92. 10.1016/j.jare.2023.02.005

13.

WarburgO. On the Origin of Cancer Cells. Science (1956) 123(3191):309–14. 10.1126/science.123.3191.309

14.

Vander HeidenMGCantleyLCThompsonCB. Understanding the Warburg Effect: The Metabolic Requirements of Cell Proliferation. Science (2009) 324(5930):1029–33. 10.1126/science.1160809

15.

WangZJiangQDongC. Metabolic Reprogramming in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Biol Med (2020) 17(1):44–59. 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2019.0210

16.

ShenLO'SheaJMKaadigeMRCunhaSWildeBRCohenALet alMetabolic Reprogramming in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Through Myc Suppression of TXNIP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2015) 112(17):5425–30. 10.1073/pnas.1501555112

17.

GongYJiPYangYSXieSYuTJXiaoYet alMetabolic-Pathway-Based Subtyping of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Reveals Potential Therapeutic Targets. Cell Metab. (2021) 33(1):51–64 e9. 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.10.012

18.

AgostiniMManciniMCandiE. Long Non-Coding RNAs Affecting Cell Metabolism in Cancer. Biol Direct (2022) 17(1):26. 10.1186/s13062-022-00341-x

19.

XuYQiuMShenMDongSYeGShiXet alThe Emerging Regulatory Roles of Long Non-Coding RNAs Implicated in Cancer Metabolism. Mol Ther (2021) 29(7):2209–18. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.03.017

20.

YangJLiuFWangYQuLLinA. Lncrnas in Tumor Metabolic Reprogramming and Immune Microenvironment Remodeling. Cancer Lett (2022) 543:215798. 10.1016/j.canlet.2022.215798

21.

HuarteM. The Emerging Role of Lncrnas in Cancer. Nat Med (2015) 21(11):1253–61. 10.1038/nm.3981

22.

WangKCChangHY. Molecular Mechanisms of Long Noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell (2011) 43(6):904–14. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.018

23.

DasPKSiddikaARashelKMAuwalASohaKRahmanMAet alRoles of Long Noncoding RNA in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Med (2023) 12(20):20365–79. 10.1002/cam4.6600

24.

ShinVYChenJCheukIWSiuMTHoCWWangXet alLong Non-Coding RNA NEAT1 Confers Oncogenic Role in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Through Modulating Chemoresistance and Cancer Stemness. Cell Death Dis (2019) 10(4):270. 10.1038/s41419-019-1513-5

25.

SharmaUBarwalTSKhandelwalAMalhotraARanaMKSingh RanaAPet alLncrna ZFAS1 Inhibits Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Targeting STAT3. Biochimie (2021) 182:99–107. 10.1016/j.biochi.2020.12.026

26.

FiedlerJBreckwoldtKRemmeleCWHartmannDDittrichMPfanneAet alDevelopment of Long Noncoding RNA-Based Strategies to Modulate Tissue Vascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol (2015) 66(18):2005–15. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.081

27.

MuysBRLorenziJCZanetteDLLimae BRBde AraújoLFDinarte-SantosARet alPlacenta-Enriched Lincrnas MIR503HG and LINC00629 Decrease Migration and Invasion Potential of JEG-3 Cell Line. PLoS One (2016) 11(3):e0151560. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151560

28.

KallenbachJRasaMHeidari HorestaniMAtri RoozbahaniGSchindlerKBaniahmadA. The Oncogenic Lncrna MIR503HG Suppresses Cellular Senescence Counteracting Supraphysiological Androgen Treatment in Prostate Cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2024) 43(1):321. 10.1186/s13046-024-03233-2

29.

XuYMaoSFanHWanJWangLZhangMet alLINC MIR503HG Controls SC-Beta Cell Differentiation and Insulin Production by Targeting CDH1 and HES1. Adv Sci (Weinh) (2024) 11(13):e2305631. 10.1002/advs.202305631

30.

TianJYangLWangZYanH. MIR503HG Impeded Ovarian Cancer Progression by Interacting with SPI1 and Preventing TMEFF1 Transcription. Aging (Albany NY) (2022) 14(13):5390–405. 10.18632/aging.204147

31.

WangSMPangJZhangKJZhouZYChenFY. Lncrna MIR503HG Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Promotes Apoptosis in TNBC Cells via the miR-224-5p/HOXA9 Axis. Mol Ther Oncolytics (2021) 21:62–73. 10.1016/j.omto.2021.03.009

32.

MeerbreyKLHuGKesslerJDRoartyKLiMZFangJEet alThe Pinducer Lentiviral Toolkit for Inducible RNA Interference In Vitro and In Vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2011) 108(9):3665–70. 10.1073/pnas.1019736108

33.

GenialisTM. An NGS Data Management and Analysis Software (2025). Available online at: https://genial.is/expressions (Accessed April 7, 2025).

34.

DobinADavisCASchlesingerFDrenkowJZaleskiCJhaSet alSTAR: Ultrafast Universal RNA-Seq Aligner. Bioinformatics (2012) 29(1):15–21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635

35.

DanecekPBonfieldJKLiddleJMarshallJOhanVPollardMOet alTwelve Years of Samtools and Bcftools. GigaScience (2021) 10(2):giab008. 10.1093/gigascience/giab008

36.

LiaoYSmythGKShiW. Featurecounts: An Efficient General Purpose Program for Assigning Sequence Reads to Genomic Features. Bioinformatics (2013) 30(7):923–30. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656

37.

SubramanianATamayoPMoothaVKMukherjeeSEbertBLGilletteMAet alGene Set Enrichment Analysis: A Knowledge-based Approach for Interpreting Genome-Wide Expression Profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2005) 102(43):15545–50. 10.1073/pnas.0506580102

38.

RingnérMFredlundEHäkkinenJBorgÅStaafJ. GOBO: Gene Expression-based Outcome for Breast Cancer Online. PLOS ONE (2011) 6(3):e17911. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017911

39.

MahmoudROrdóñez-MoránPAllegrucciC. Challenges for Triple Negative Breast Cancer Treatment: Defeating Heterogeneity and Cancer Stemness. Cancers (Basel) (2022) 14(17):4280. 10.3390/cancers14174280

40.

XiongNWuHYuZ. Advancements and Challenges in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Comprehensive Review of Therapeutic and Diagnostic Strategies. Front Oncol (2024) 14:1405491. 10.3389/fonc.2024.1405491

41.

BaranovaAKrasnoselskyiMStarikovVKartashovSZhulkevychIVlasenkoVet alTriple-Negative Breast Cancer: Current Treatment Strategies and Factors of Negative Prognosis. J Med Life (2022) 15(2):153–61. 10.25122/jml-2021-0108

42.

KansaraSSinghABadalAKRaniRBaligarPGargMet alThe Emerging Regulatory Roles of Non-Coding RNAs Associated With Glucose Metabolism in Breast Cancer. Semin Cancer Biol (2023) 95:1–12. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2023.06.007

43.

XuJ-LXuQWangY-LXuDXuW-XZhangH-Det alGlucose Metabolism and Lncrnas in Breast Cancer: Sworn Friend. Cancer Med (2023) 12(4):5137–49. 10.1002/cam4.5265

44.

DuYWeiNMaRJiangS-HSongD. Long Noncoding RNA MIR210HG Promotes the Warburg Effect and Tumor Growth by Enhancing HIF-1α Translation in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Front Oncol (2020) 10:580176. 10.3389/fonc.2020.580176

45.

HanGBaiXLiFHuangLHaoYLiWet alLong Non-coding RNA HANR Modulates the Glucose Metabolism of Triple Negative Breast Cancer via Stabilizing Hexokinase 2. Heliyon (2024) 10(1):e23827. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23827

46.

CaoXFanQL. Lncrna MIR503HG Promotes High-Glucose-Induced Proximal Tubular Cell Apoptosis by Targeting miR-503-5p/Bcl-2 Pathway. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes (2020) 13:4507–17. 10.2147/DMSO.S277869

47.

HanXLiBZhangS. MIR503HG: A Potential Diagnostic and Therapeutic Target in Human Diseases. Biomed & Pharmacother (2023) 160:114314. 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114314

48.

FuJDongGShiHZhangJNingZBaoXet alLncrna MIR503HG Inhibits Cell Migration and Invasion via miR-103/OLFM4 Axis in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. J Cell Mol Med (2019) 23(7):4738–45. 10.1111/jcmm.14344

49.

QiuFZhangMRZhouZPuJXZhaoXJ. Lncrna MIR503HG Functioned as a Tumor Suppressor and Inhibited Cell Proliferation, Metastasis and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Bladder Cancer. J Cell Biochem. (2019) 120(6):10821–9. 10.1002/jcb.28373

50.

YonemoriKTsutaKOnoMShimizuCHirakawaAHasegawaTet alDisruption of the Blood Brain Barrier by Brain Metastases of triple-negative and Basal-Type Breast Cancer but Not HER2/Neu-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancer (2010) 116(2):302–8. 10.1002/cncr.24735

51.

PardridgeWMBoadoRJFarrellCR. Brain-Type Glucose Transporter (GLUT-1) Is Selectively Localized to the Blood-Brain Barrier. Studies with Quantitative Western Blotting and in situ Hybridization. J Biol Chem (1990) 265(29):18035–40. 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)38267-x

Summary

Keywords

gene expression, lncRNA, RNA-seq, triple-negative breast cancer, glucose

Citation

Reid VA, Yang B, Russo K, Sedano MJ, Choudhari R, Ramos EI and Gadad SS (2025) Molecular Effects of Glucose on MIR503HG-Regulated Genes in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 82:15206. doi: 10.3389/bjbs.2025.15206

Received

01 July 2025

Revised

20 October 2025

Accepted

19 November 2025

Published

17 December 2025

Volume

82 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Reid, Yang, Russo, Sedano, Choudhari, Ramos and Gadad.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shrikanth S. Gadad, shrikanth.gadad@utrgv.edu

† Present address: Ramesh Choudhari, MLM Medical Labs, Memphis, TN, United States

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.