Abstract

Leadership models in the cultural and creative sectors are frequently based on collective, shared, or distributed structures. In recent decades, research on these plural forms has yielded insights in the form of typological models and empirical studies. This article seeks to examine two issues in the literature on plural leadership that have received insufficient attention. The first is how cultural organizations combine and integrate multiple leadership models. The use of horizontal co-leadership at the macro (organisational) level alongside either vertical or horizontal leadership of embedded projects managed by teams is one example. Little is known about how the existence of distinct leadership styles at the macro and meso levels influences the career paths of individuals and organizations. The second is an inquiry into the evolution of leadership models in cultural organizations over time. This is especially important when an organisation transitions from a startup to a successful enterprise and expands its operations internationally. To empirically investigate these issues, we propose a single case study of Snøhetta, a multinational architecture firm. The results of this case study allow for a better understanding of how forms of collaborative leadership style can influence the career paths of people and organizations, and how it is possible to find a balance between the paradoxical institutional logic on which management and leadership of creativity is based. In other words, how the constellations of relationships that are generated make organizations with this leadership style more resilient and sustainable by virtue of being more transparent, open, and generous.

Introduction

Recent contributions to the literature on arts and cultural management situate cultural leaders as social agents (Price, 2017), whose capacity to enable artistic work to flourish (Mandel, 2017) may be explained by talent for advocacy and facilitation (Sutherland and Gosling, 2010). As individuals, cultural leaders are revered because they are thought to be exceptional individuals with charismatic personalities (Nisbett and Walmsley, 2016). Professionally, they are esteemed for their ability to balance a somewhat challenging juxtaposition of artistic, creative, and economic objectives (Lampel et al., 2000; DeFillippi et al., 2007). In a nutshell, the personality of a cultural leader unites the traits of an entrepreneur (success at the project or organisational level) who is a generous (attentive to the needs of the field or sector) public figure (demonstrates interest in larger societal issues and public concerns) (Price, 2017).

However, the emphasis on the individual traits of leaders may obfuscate significant aspects of the actual managerial models and leadership configurations utilised in the cultural and creative sectors. One important consideration is that so-called collective, plural, or shared models of leadership between two or more people have over time become the standard executive constellation (Hodgson et al., 1965) within management for cultural and creative organizations in many countries (Royseng, 2008; Reid and Karambayya, 2009; Fjellvaer, 2010). Common configurations at the tops of organizations are premised on pluralistic models with two or more individuals having joint responsibility of leading the organisation with separate managerial areas of responsibility (Denis et al., 2012; Gibeau et al., 2016).

Another factor that may condition leadership styles and performance is that cultural and creative organizations’ main line of activity is the acquisition, management, and execution of temporary projects (Gann and Salter, 2000; Grabher, 2002). Bureaucratic models and organisational structures therefore tend towards horizontal rather than vertical alignment. This is because horizontal structures are better for facilitating the management and leadership of temporary projects (Müller et al., 2018), whilst providing intra-organisational infrastructure and resources that facilitate and support project work (Grabher, 2002; Cohendet and Simon, 2007).

Further, leadership by constellations within project-driven horizontal structures may prove to be challenging. This could be related to cultural differences across geographic contexts (Mandel, 2017; King et al., 2019); conflicts between leaders (Reid and Karambayya, 2009); or intra-organisational tensions between the need for creative autonomy (of the project teams and their members) and performance at the organisational level (Lampel et al., 2000; Gilson et al., 2015). Finally, the variety of relationships with external stakeholders (from providers to competitors, politicians, or media) in project-based organizations implies that there is not a single hierarchical path or procedure, but several often-complementary relations (more or less dissonant) to track and monitor. Solutions are therefore most likely to be both customised and context-specific, as there are few standard recipes or procedures to draw upon (Cohendet and Simon, 2007).

It should therefore be of no surprise that leadership and management of cultural organizations requires capacity to address competing institutional logics (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983; Peterson and DiMaggio, 1986; Thornton et al., 2008). Among those identified we find the actual influence of both internal and external stakeholders on the mission, goals, strategy, and resource of the organization; its governance model, defined both by the ownership or legal nature and by how priorities are set, or the executive management is elected (or changed); the values of the organization and its professionals; and obviously, its history and evolution. Others have synthesised these into five logics as they relate to profession, mission, bureaucratic, resource and business aspects of leadership and governance (Fjellvaer, 2010).

Thus, our starting rationale is an interest in assessing the efficiency and potential of one of the perspectives on plural leadership constellations that the literature has conceptualised: managerial shared leadership (Döös and Wilhelmson, 2021). How can managerial shared leadership help strike a balance between the paradoxical institutional logics management and leadership of creativity is premised upon? Is this constellation more resilient because they are considered more transparent, open, and generous? Our knowledge of creative and cultural sector organizations has yet to yield in-depth insight into the way co-leadership at the top is combined with other plural models at the embedded level of temporary projects. Most of the literature consider either plural leadership forms at the top and their impact [some examples are Royseng (2008), Reid and Karambaya (2009), Nisbett and Walmsley (2016)] or leadership of teams managing an organisation’s portfolio of temporary projects (Grabher, 2002; Müller et al., 2018). Combining levels of analysis, by considering plural leadership of an organisation in tandem with how leadership constellations at the top facilitate or hamper the leadership and management of intra-organisational project teams is less common. Drawing together these perspectives would enable the study of cultural leadership as a confluence of top-down (formally imposed) structural influence together with interactional and emergent bottom-up strategies.

An added benefit of combining perspectives is that it will enable us to focus on two issues in the broader literature on plural leadership, of which managerial shared leadership is a part that has received inadequate attention. The first is how cultural organizations combine and integrate multiple leadership models. The second is an inquiry into the evolution of leadership models in cultural organizations over time. This is especially important when an organisation transitions from a startup to a successful enterprise and expands its operations internationally.

To examine these issues, we propose a case study based on the international architecture firm Snøhetta. The rationale for our choice is linked to some of the company principles—sustainability, uniqueness, generosity through shared public spaces, collaborative work, and co-creation inside the team and with the clients. These organisational values are not common either in creative industry firms or in society in general. Even as of 2019 before COVID, Snøhetta justifies the rationale of adhering to these principles by showing how an entrepreneurial creative studio can be successful in applying ‘soft’ values and approaches to work in very competitive market environments. We therefore believe the organisation provides an interesting setting for studying the use of managerial shared leadership and its potential resilience.

The article is structured as follows. In the next section, we outline the theoretical framework, based on a review of recent literature on plural leadership models. Following that, we detail our methodology, data collection and analysis procedures, the results from the case study, and the discussion and conclusions in the following sections.

Literature review

In this literature review, the concepts and approaches to researching leadership at the organisational or embedded project level will be presented and discussed. The review will then transition to a discussion of some of the competing logics and paradoxes that leaders and managers of cultural organizations will have to confront in the course of their work. Defining leadership and management functions, as justified by the tensions and paradoxes faced by cultural and creative organizations, may provide the framework and concepts for an analysis of managerial shared leadership within these organizations.

Whether “manager” and “leader” refer to the same or different categories of people remains a point of contention in the literature. People are split on whether or not these two functions are distinct jobs in and of themselves (Bolden, 2004). In the first case, there are those who take the position that leaders are distinguishable from managers because of their personalities (Burns et al., 2010) and exceptional ability to formulate organisational visions and direction, engender confidence, and effect the required change despite adversity (Kotter, 1996; Bolden et al., 2011, pp. 25–30). This approach may also include some who correlate leadership with a capacity to protect artistic autonomy and work from instrumental concerns and market imperatives (Royseng, 2008). In the latter faction, there are those who consider management to be a profession with numerous facets. As an illustration of this school of thought, Mintzberg (1973) asserts that leadership is only one of the many responsibilities of a manager. This is congruent with the view articulated by Döös and Wilhelmson (2021) that some have a semantic preference for the term leader over manager, even though both jobs are linked in practise. Individuals’ placement in a given group is always specific to their circumstances and the context wherein the organisation they represent is active. In brief, this position implies that while we believe that not every leader is a good manager, some managers can have the makings of future leaders. For practical purposes, it is difficult to compartmentalise roles: people may, depending on the circumstances, need to act as either leaders, managers, or both. As the focus of the article is on the interrelationship between both roles, we will not seek to differentiate between leaders and managers, The second consideration is the usage of terminology such as model or constellation to describe how to arrange leadership and managerial functions. As an alternative to model, a constellation describes how and in what way the various tasks and responsibilities associated with these functions are being divided between people (Döös and Wilhelmson, 2021). The “executive role constellation” as a conceptual framework to analyse collective or shared leadership by teams consists of three dimensions: “specialisation,” “differentiation,” and “complementarity” (Hodgson et al., 1965). When combined, they yield a useful framework for analysing managerial configurations within the shared role space (Gibeau et al., 2016). Specialisation is the extent to which each individual’s roles are broad and comprehensive or focused on specific areas. The differentiation dimension is the degree to which roles overlap, creating (or not creating) zones of mutual replacement or duplication. Complementarity can be broken down into two components: how well the people’s duties overlap, and how well they are able to coordinate their efforts within the shared role area. Given that constellation, as defined, is a more conceptually dense term than the neutral model, the article uses constellation to refer to the way the responsibility for leading an organisation is distributed among people in leadership roles and implemented in practise.

Having established our understanding of leadership, management, and possible ways to assess constellations within which they manifest as managerially shared forms of leadership, we turn to the question of how to define and interpret the variety of so-called plural forms of leadership in the next section.

Plural forms of leadership—an overview

It is not an easy task to make sense of the concepts of leadership constellations that involve more than a unitary leader at the top of an organisation. As Table 1 indicate, there are at least five different conceptualisations, each with an established research stream, that partly overlap and do not always speak with one another. What binds them together is that they focus on forms of leadership and managerial practice in the plural, by which it is inferred that the actual responsibility can be shared or distributed throughout an organisation, always with two or more people involved as a part of the constellation (Denis et al., 2012; Döös and Wilhelmson, 2021).

TABLE 1

| Concept | Definition | Analytical perspective | Focus and emphasis | Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distributed Leadership | A leadership approach whereby responsibility is dissociated from formal organisational roles, and people at all levels are given the opportunity to influence the overall direction and functioning of the organisation. Bolden et al. (2011) | • How to diffuse leadership away from the organization’s apex to develop leadership practises throughout the entire organisation | • Focus on understanding and explaining the role and nature of distributed leadership and how the approach can contribute to organisational change | Spillane and Diamond (2007), Bolden (2011), Bolden and Donato (2011) |

| • Emphasis on how leadership as a practice is developed interactively and situations where it is enacted (organisation as unit of analysis) | ||||

| Shared Leadership | A dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of group or organizational goals or both Pearce and Conger (2003) | • How leadership responsibilities are shared or divided among project team members through either formal designation or interactive emergence | • Focus on leadership as an emergent group-based phenomenon where influence is dispersed and configuration is horizontal, whereby group members take on tasks usually handled by designated or elected leaders | Pearce and Conger (2003), Pearce (2004), Müller et al. (2018), Zhu et al. (2018) |

| • Emphasis on room for individual action within the dynamic frame provided by group dynamics | ||||

| Co-Leadership | A leadership constellation where a group of two, three, or more people situated or pooled at the top leads an organisation Alvarez and Svejenova (2005), Denis et al. (2012) | • How co-leadership constellations can be considering effective managerial structures, adept at navigating intraorganizational complexity, and balance competing tensions | • Focus on acknowledging that leadership constellations can have more than two people, and that these constellations are plural in nature, e.g., leadership can be shared, distributed, or combined in different ways | Alvarez and Svejenova (2005), Denis et al. (2012), Sergi et al. (2017), Reid and Fjellvær (2022) |

| • Emphasis on the characteristics of the organizational context within which co-leadership takes place. These settings are defined as having multiple (organisational) objectives, diffuse power structures, and knowledge-based work processes (Denis et al., 2007) | ||||

| Dual Leadership | A management structure in which two leaders of equal standing divide the top management position and functions between them so that each is responsible for different organizational domains. Fjellvær (2010) | • How leaders relate to one another to achieve organisational goals and avoid conflict | • Focus on potential for conflict and how to avoid it. Largely premised on leader being mandated or appointed by a board | Reid and Karambaya (2009), Fjellvær (2010), Reid and Karambaya (2016), Gibeau et al. (2016) |

| • Emphasis on competing logics (e.g., tension between art and commerce) | ||||

| Managerial Shared Leadership | A constellation with a few individuals being mutually responsible for the tasks (administration, leadership towards goals, and organising working conditions for others) included in holding a managerial position. Döös and Wilhelmson (2021, p.717) | • How leadership in practice either emerges within or is being imposed upon a constellation of any number of managers sharing responsibilities | • Focus on how leadership constellations are structured rather than the number of people and their relationship with one another | Döös and Wilhelmson (2021) |

| • Emphasis on both how these structures relate to organisational aspects (equality (of standing), work tasks, and organisational units) |

Examples of concepts and definitions of plural types of leadership.

As an example of the confusion, take the article by Gibeau et al. (2016) that defines co-leadership as situations where “ … two people might successfully share an organizational leadership role on an equal footing.” (p.225). Conversely, another definition of co-leadership situates the practice as a constellation that also includes “…trios or other smaller groups” (Reid and Fjellvær, 2022). This may be explained by the fact that co-leadership as a plural construct is an evolution of an earlier concept of dual leadership (Reid and Karambayya, 2009; Fjellvaer, 2010) which focused on dyads of leaders in specific organizations from particular sectors, of which museums (Fjellvaer, 2010) and performing arts organizations (Döös and Wilhelmson, 2021) are interesting and relevant settings in the present context. However, the literature on co-leadership (Reid and Fjellvær, 2022) is critical of the concept of managerial shared leadership. This is because they see the concept as a conflation of shared leadership with co-leadership by a formally defined leadership constellation.

Part of the criticism can be explained by the previous research. The literature on management of cultural and creative organizations has put more emphasis in investigating different forms of behaviour relative to the more artistic and creative output rather than profile and strategies of managerial stratums (Peltoniemi, 2015). Another is the level of analysis and concerns of the different traditions detailed in Table 1. The older notions of shared and distributed leadership are primarily concerned with investigating and theorising leadership and management practise that diffuse horizontally, or bottom-up (Pearce, 2004; Bolden, 2011; Ebbers and Wijnberg, 2012), rather than models vertically imposed by the constellation leading from the top (Fjellvaer, 2010). Indeed, as others have pointed out, the co- and dual-leadership literature has a particular affinity with how to establish trust and/or avoid conflicts between leaders and managers of an organisation (Ebbers and Wijnberg, 2017). Thus, the overlap has in practice more to do with whether the level of analysis focuses on teams working on projects (Gann and Salter, 2000; Grabher, 2002) or an organisation (Reid and Fjellvær, 2022), or whether the leadership constellation is imposed via selection or emergent (Denis et al., 2012). Thus, studying the efficacy and efficiency of managerial constellations, two aspects require consideration. First, the structural form of the constellation of leaders (i.e., whether the constellation has a joint, functional, horizontal, or vertical orientation) and the formal organisational aspects (i.e., if the managers are equals or non-equals hierarchically, if the area of influence is within or across organisational units, and if tasks are merged or divided) (Döös and Wilhelmson, 2021).

In brief, combining a perspective of the constellation with these organisational aspects is what distinguishes managerial shared leadership as a concept: it bridges these concerns. Since our interest is in analysing the resilience and potential of horizontal leadership models premised on autonomous teams that manage their work on temporary projects across units with a different constellation leading the organisation overall, we believe there is some purchase in adopting the plural concept of managerial shared leadership in the article.

In the next section, we turn to some of the challenges encountered by those with managerial responsibilities working within this model.

The challenges facing cultural leaders and managers: balancing paradoxes

As discussed in the preceding section, there are various constellations of plural leadership based on distributed (Ebbers and Wijnberg, 2017), shared (Bolden, 2011), or collective (Reid and Fjellvær, 2022) configurations with varying levels of embeddedness (Döös and Wilhelmson, 2021) in organisations. These constellations in and by themselves, however, do not explain why an organisation or a project fails or succeeds. Failure and success are heavily influenced by the type of organisation and the nature of the ventures. For example, entrepreneurial cultural organisations founded by one individual or a group of cultural entrepreneurs that become growing concerns over time (DiMaggio, 1982) differ from established non-profit arts and cultural organisations whose leaders are chosen and appointed by boards for a set period of time (Reid and Karambayya, 2009).

A richer analysis may therefore want to consider contextual issues that may or may not influence the performance of managerial shared leadership constellations. Some of these variables, frequently tied to organisational or project-specific objectives, are the geographical political and cultural framework an organisation is embedded in, cultural sector specificities, the legal form of entities (public, profitability), organizational philosophy/model (hierarchical, self-managed, by project …), size of the organization, and maturity of the organization or project (start-up vs. consolidated organization). This section of the review will discuss some of these.

Whilst managers obviously want to realize organizational objectives, their ambitions for outcomes may conflict with some or all the plural objectives of the professionals involved in artistic or creative work (DeFillippi and Arthur, 1998; Lampel et al., 2000; DeFillippi et al., 2007). In small or newly created organizations, i.e., entrepreneurial organisations, the objectives of teams and organization are generally well aligned. Differences are usually resolved with the departure of those partners who are dissatisfied with the developed mission and strategy adopted by the organization. As an organization grows and expands operations, the differences between its interests and those of its professional teams must by necessity be aligned to better ensure successful outcomes. This requires balancing the need to maintain and continue attracting talent while guaranteeing the sustainability and viability of the organisation’s project. Thus, in situations faced by many cultural organisations where creativity is at the core and outcomes are both complex and uncertain, horizontal approaches to leadership work well because their use dictates intensive interaction among team members (Müller et al., 2018). These approaches develop naturally through practice in many cultural organisations because of the founders’ natural drive and inspirational personalities. These character traits help cultural managers keep track of the overall vision and direction, manage fairness in leadership assignments, and trigger progression by asking the team for solutions (Bolden, 2011). Delegating some of the responsibility and initiative will thus provide a setting for working collaboratively to develop balanced solutions.

The management of creative resources, both tangible and intangible, is thus one of the most significant obstacles facing managers of organizations in the cultural and creative sectors (Eikhof and Haunschild, 2007). As a result of the difficulties inherent in carrying out these responsibilities (Lampel et al., 2000), management becomes a balancing act when trying to strike an equilibrium between either economic results or mission fulfilment, even in the case of cultural and creative for-profit organisations. Adding to the intricacy is the potential influence of exogenous factors on managerial performance, which further complicates the task of balancing these aspects. Differences in national contexts, policy regimes, governance models, organisational objectives, and the demand for transparency are just a few examples (Mandel, 2017; King et al., 2019).

Ambidextrous leadership has been discussed in the literature as one explanation of how to succeed operationally with leadership and management of creativity (Rosing et al., 2023). A style based on ambidexterity necessitates approaches that are both open enough to allow for creative experimentation while also closed enough to allow for effective implementation control. One example of what may constitute ambidextrous leadership and management is the development of organisational systems that encourage the efficient recruitment, retention, and performance of creative employees without stifling them (Cohendet and Simon, 2007).

Nonetheless, our concern is on the challenges faced by cultural managers when acting as ambidextrous leaders. Another strand of the literature has formally conceptualised these as the paradoxes of cultural management (DeFillippi et al., 2007), defined as:

“…a group of conditions that lead to contradiction or defy intuition. Paradoxes prompt exploration of whether the conditions that are inferred are actually true. A paradox sparks further inquiry and the recognition of assumptions and ambiguities. The exploration prompted by paradox leads to rethinking and considering the phenomena at hand.” (p.514).

Four paradoxes have been identified: the difference paradox (the need to craft or standardise practises; the balance between creativity and economic efficiency); the distance paradox (couple or decouple routine work); the globalisation paradox (reconcile or separate local and global arenas of activity); and the identity paradox (creating individual or collective identities, reputations, and careers). These are some of the issues that need to be considered by managers and leaders, whether they are at the “top” of the organisation (Denis et al., 2012) or are embedded as leaders of temporary projects (Grabher, 2002).

Furthermore, in the case of architecture, there is a need to reconcile the “Artist-Entrepreneur Logic” (emphasis on architects’ roles as artists and creative entrepreneurs) and the “Engineer-Manager” Logic (emphasis on architects’ roles as problem solvers and managers who prioritise technology, efficiency, and practicality in their work) (Thornton et al., 2005). Depending on conditions, (e.g., the historical epoch, societal context, and economic factors) one of these logics becomes the most prominent, influencing the architectural styles and approaches of that time. In both cases, however, logics and paradoxes follow a cyclical nature of shifts, oscillating between prioritizing one pole of the continuum (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983; Peterson and DiMaggio, 1986; Thornton et al., 2005). This cyclical pattern has been a defining characteristic of not just the architectural profession’s evolution, but the cultural sector overall (Bonet and Donato, 2011; Bonet and Négrier, 2018).

Thus, being able to juxtapose and balance logics that require ambidextrous approaches (Rosing et al., 2023), through managerial shared forms of leadership is one theoretical explanation to successful leadership styles and organisational performance.

Methods

The study was conducted as a single case study with embedded units of analysis (Yin, 2018). By a single case-study with embedded units of analysis, we mean the identification of different groups within the organisation (e.g., top, and middle management, administrative staff, architects, and interns) across units. As an example, the cases and informants represented the managerial shared leadership of the organisation, the manager of a country office, architects and interns working on project teams with shared and distributed models, alongside administration in charge of defining and structuring management and leadership models. Who the informants were are detailed in Table 2.

TABLE 2

| Name | Function | Office |

|---|---|---|

| Informant 1 | Chief Executive Officer | Main Office |

| Informant 2 | Creative Manager of country office | Country Office |

| Informant 3 | Country Executive Officer | Country Office |

| Informant 4 | Senior Architect—Project Leader | Main Office |

| Informant 5 | Senior Architect | Country Office |

| Informant 6 | Architect—Board Member | Main Office |

| Informant 7 | Junior Architect | Main Office |

| Informant 8 | Intern | Country Office |

| Kjetil | Founding Architect | Main Office |

Overview of the informants.

A case study is a research method that focuses on the intensity (details and information richness) of an analysis of a defined bounded unit (a person, community, or organisation) in relation to developments and context (where and when of the setting) (Flyvbjerg et al., 2011). The exploratory dimension is prominent in this study because we seek to understand how a phenomenon (managerial shared leadership) can be used to balance dichotomous conflicting logics. Furthermore, a case study elucidates the contextual conditions that may (or may not) cause a phenomenon to occur, thereby identifying links between processes and outcomes. Therefore, it is an appropriate and justified methodology for a study investigating managerial shared leadership constellations in an international architecture firm. This is because the case study approach has been found suited for answering questions about how something was initiated or occurred in a particular way (Flyvbjerg et al., 2011; Yin, 2018). In addition, the emphasis on data depth and richness provides a level of insight that may aid in the advancement of the research field by serving as input for the development of new hypotheses and research questions (Flyvbjerg et al., 2011).

Evidently, a qualitative case study approach has some limitations. While findings from one or a few case studies may contradict and thus call into question established knowledge and assumptions (Flyvbjerg, 2006), generalisations about a population or universe are not possible. Case study generalisation is typically based on contrasting findings to corroborate or refute established theory, also known as analytical generalisations (Yin, 2018).

To ensure transparency and possibilities for replication, the study was designed as a stepwise process with five phases. These were 1) negotiating access, 2) collecting data, 3) analysis and interpretation, 4) contrasting results and findings with theory, and 5) writing the case report. Rather than strictly following a predefined recipe (Pan and Tan, 2011; Yin, 2018), this simplified procedure took cues and inspiration from examples from best practice, premised on a belief that the most important methodological principle is transparency of processes to enable replication.

We began by negotiating access to Snøhetta, by pitching the idea of conducting research on their leadership constellations. The rationale for selecting Snøhetta was a lack of case studies on entrepreneurial creative organisations in the arts and cultural management literature, which, with notable exceptions (Alvarez and Svejenova, 2005; Cohendet and Simon, 2007; Ebbers and Wijnberg, 2017) primarily focuses on the arts end of the cultural and creative sectors, through empirical research into art museums and performing arts organisations (Royseng, 2008; Reid and Karambayya, 2009; Fjellvaer, 2010;Mandel, 2017; Byrnes and Brkić, 2019; Reid and Fjellvær, 2022).

After being granted access, data was gathered through interviews and participant observations during two field trips: one to the main office and another to one of the country offices. In-person interviews lasting 60–120 min were conducted while we observed how people worked and interacted, through participating in communal activities such as having lunch with the staff.

The analytical strategy used was a proprietary take on thematic analysis that included manual coding and categorization of notes and interview transcripts. Thematic analysis has been described as a “rather basic, flexible tool” that entails coding the data by assigning “labels to segments of potentially relevant data.” (Herzog et al., 2019) We used close reading to sort fragments and chunks of texts gradually and iteratively into different thematic categories. The purpose of iteration was to reduce the number of thematic codes and categories.

Two choices were made to avoid biases in interpretations. First, it was decided to incorporate triangulation of data sources into the research design by including informants with varying levels of managerial responsibility, from various departments and offices, and with varying levels of seniority. Second, based on the reporting rationale, it was decided to write up the case study in a narrative style, with extensive use of quotations. The justifications were, on the one hand, that the reporting style helped to better illustrate the analysis process (Eldh et al., 2020), while also ensuring transparency by allowing the reader(s) to make their own decisions about whether our interpretations of the findings of the themes accurately reflect the participants’ accounts (Noble and Smith, 2015).

Following this largely inductive approach to collecting and analysing data, the identified data categories and concepts were compared to literature and theories of cultural management and leadership. The rationale was to ensure alignment between theory and data, as well as analytical (theoretical) validity and generalizability relative to our interpretations (Pan and Tan, 2011).

Based on this process, it was decided to focus the case reporting on three thematic areas: Snøhetta’s (as an organization’s) leadership constellation, project management and leadership, and recruitment. The findings are presented in the following section.

Results from the case

Introduction and presentation

Snøhetta is an international architecture and design studio premised on a holistic, horizontal, and co-creative organisational model. It employed 230 professionals in 2019, located in seven permanent offices (Oslo, New York, Hong Kong, Adelaide, Paris, San Francisco, and Innsbruck) and multiple global project offices. These people were at the time simultaneously involved in 300 projects and 30 building sites.

Snøhetta is a conceptual and philosophical grounding of people taking part in projects. The studio is an unusual firm in a highly competitive world of professional architecture. The inherent high risk and uncertainties, and individual choices and preferences of some of the founders, led to some of the colleagues progressively leaving the firm and selling their part. To secure financial stability, Fritt Ord (a Norwegian foundation devoted to supporting freedom of expression and a free press) became a minority owner in 2016, acquiring a twenty percent stake of the company.

Another particularity is that individual architects and designers do not sign off on their designs and buildings. Different professionals (from administrative staff to designers, architects, and technicians) work together in teams out of shared, mixed office spaces, with salaries based on a relatively horizontal and transparent pay scale. Instead, the people working for the studio engage in horizontally shared creative processes that lead to precise outputs as well as social outcomes, either in the form of products (the result of design processes and projects) or as places (in the case of architectonic processes and landscapes).

The leadership constellations and organizational structures are essentially built on transparent and participatory values. Fortnightly, there are internal meetings where employees can learn about status for ongoing projects and get information on the company’s position and financial situation. Additionally, employees have representation at the board level; everyone knows the salary table of the architects (designers’ pay scale is governed to a larger degree by market prices).

The organizational leadership constellation of Snøhetta

The evolution of the current leadership constellation of Snøhetta has been shaped and formed by visionary entrepreneurs, based on a Nordic approach to work, and a generational spirit taking a holistic and collective approach to creativity, with emphasis on generosity and social responsibility.

The gradual transition from being an entrepreneurial start-up to Snøhetta’s current complex international operation is the combined effects of three main factors. Primarily, the resilient capacity to overcome periodic difficult economic moments, with many high and low conjectures determined in part by the wider economy at large and demand from the construction sector. Secondly, an aptitude for maintaining an artisanal approach to work processes, compatible with developing a distinct brand value, based on a work model and interactions with clients at a very personal level. Thirdly, international expansion and a multi-disciplinary approach compatible with strong, value-based local grounding. Those three elements are why Snøhetta has survived and existed for nearly 30 years.

To comply with the logics and demands of these factoring conditions, internal leadership and management of work at the company combines horizontal relationships (everybody’s opinion and voice are taken into account, as it corresponds to a creative company) with projects concurrently running according to the specific scope and scale of the task (project managers, project leads, and creative leads working together in constellations premised by the size of the project).

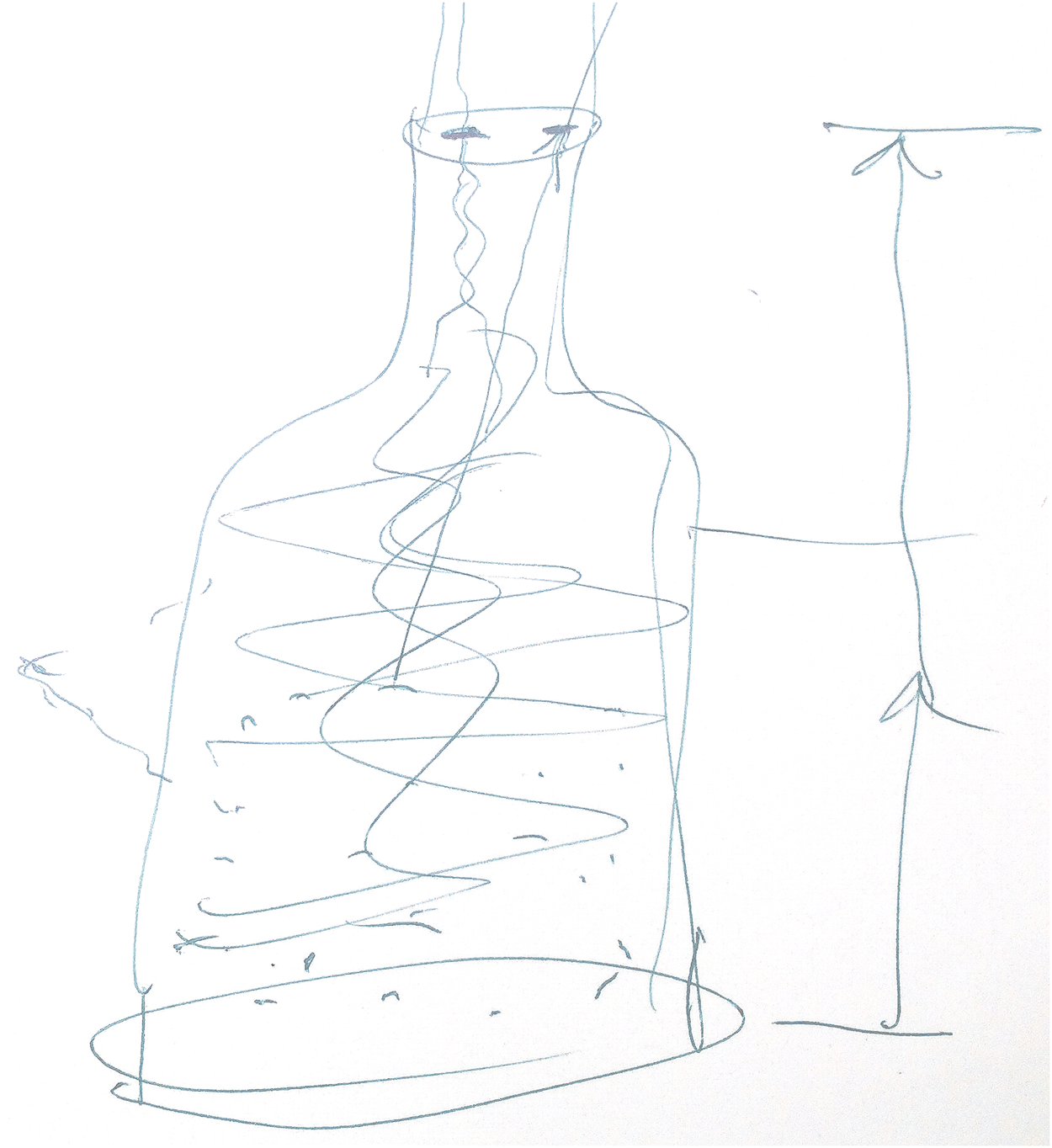

Kjetil has never had any management training. “I don’t think I’d manage anyone. Motivation needs management. Leadership needs inspiration…How can you actually create game-changing architecture, for instance, that has a deeper meaning, is not game-changing only in the sense of aesthetics, or function, but as a total package and direction in society? How do you put people together that manage to think game-changers? And we found that cannot be managed.

Let me do maybe one diagram (see Figure 1). What I do on the management side is maybe just to create the bottle. And we know there is a bottleneck somewhere for a project, for an organisation. Up here somewhere, there is a goal, maybe. And then we let all the people within the boundaries that they’d been given, spread freely inside this bottle with only one condition. You must move upwards towards the top, like champagne. We sometimes even allow people to move out of the framework. As long as they come back in, it’s okay. What we’ve seen is that those that go straight for this goal, they miss because, in time when you come to this point, the goal is here and not there. If you want to make a game-changer, you have to recognize that you have a moving goal. (…) Everyone move in their direction, and at some point, the least important sentence said in a room could be what solves the issue. (…) You have people coming together along the goal that is moved in the bottleneck and then actually pulling together into something that then becomes the project exploding out of the bottle. I think that’s where we came from.”

FIGURE 1

Leading creatives: the bottle approach.

The company has thus far relied on strong leadership but potentially lacked some management tools in present operations (current projects, international expansion, multidisciplinary approach, and recruitment policy). In addition, Snøhetta appointed an executive leader (CEO), to fulfil some of the challenges. One of the significant challenges of the CEO is to maintain a good work environment, respecting the core values of the company and being able to maintain a competitive company with high brand recognition. This implied filling the position with someone able to put in place structures and oversee the legacy and transition of the company into the future, once the current directors and majority shareholders of the holding company (and the US Company) retire.

Here, the horizontal and communal organisational model, developed by the entrepreneurial leaders, in a specific geographic (Norway) and social (egalitarian) context may present challenges and tensions when transferred to different geographies.

Informant 1’s view is that there is a risk that the company sometimes confuses the Norwegian social system with an organisational culture premised on generosity, transparency, and openness. As informant 1 comments: “We move seats every other year, and we have one table where we all have lunch together, we share toilets. That’s how we kind of show our open and transparent culture and then we have the stories we tell. (…) So, we start confusing labour issues, which is how much do you earn or about maternity leave, and our company culture.”

Some of these may stem from differences in the perception of roles and diffusion of power. Informant 2 sees his role as leader of a country office as “…creating an environment so that the people who are here like to work together.” The leadership role resembles that of a facilitator, providing an operational space for the employees to unleash creative potential (see Figure 2) by “…organising the boundary conditions, atmospherically as well as economically for them to be able to work.”

FIGURE 2

Snøhetta office Oslo- 2020.jpg by Gtit-Wiml retrieved and downloaded from Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The leadership of projects

The logic of projects requires execution and delivery in line with defined budgets and deadlines, something that requires assigning and assuming responsibilities. This has led many to flee from the self-organising chaos generated in very creative processes. Conversely, creative processes need motivation and inspiration, and both grow better in horizontal structures. The output of the balancing act is a tailor-made product, something idiosyncratically Snøhetta, reflecting Snøhetta’s conceptual core values: social engagement, generous features, and game-changing design.

Snøhetta has various categories of project leaders and managers. Small projects with a maximum of four team members have a creative lead who “owns” both the creative work and the administration of the project. The next level up is a project that is larger in scale and scope and is managed by a project lead. Typically, the project manager does not participate in the conceptual design process, which is delegated to a creative director. Thus, on a functionally shared basis, two individuals will share the managerial responsibility for delivering the project. Larger initiatives involving multiple offices, subcontractors, and a contract value exceeding 10 million euros will be led by a constellation of a project manager, project lead, and a creative leader on their team. Nonetheless, whether the structure is vertical or horizontal is also person dependent. Informant 3 describes an architect working as a project manager in the country office in the following way: “…what (project manager) likes about his job is to make the decision. So, it’s rather conservative. People are working, and (project manager) organizing, structuring, saying yes or no. In other project teams, where the hierarchy is flatter…then they’re all discussing.”

However, there is room for optimisation of constellations. As informant 1 describes, the actual practice of assigning people to constellations is challenging because of the mismatch between capacities to creatively lead design processes and the necessary skills of managing projects. These choices may have economic consequences. “For larger projects … you should probably not be an architect there, you should probably just be a project manager…what’s happened is that we’ve kind of mixed all of these things together. We’ve put a poor architect who is a creative lead into something like this. and that’s where money just goes down the drain.” Cultural perceptions and values can also interfere with the leadership of projects. In the country office, implementing the constellation is challenging. “We always have this problem of clients being very conservative and hierarchical, and they would only talk to the creative leader (informant 2) …, they never want to talk to the project leader” says informant 3. “As an example, they would not talk about everything openly with the project leader. About numbers, they mainly talk about numbers with informant 2”.

For informant 4, the magic starts when everyone gets onboard, and the conceptual work gets underway. “…. It’s not about our creation, something already made by us for a special customer. It’s something we create together, and that is tailor-made for that customer. All our processes are tailored—we are a lot about how to design a process. Not only the buildings but to come up with the results, at the end of the process”. Kjetil does not believe in the necessity to compromise between social qualities and aesthetically pleasing design. “A lot of the qualities and the designs come out of the attitude of trying to implement exactly these things into the project, and that is what makes them aesthetically valuable. The offer could not become that part of an aesthetic understanding if it hadn’t been for the social approach. So the aesthetics follow the social approach in many ways.” In his opinion, “there is no contradiction between aesthetics, great experiences, emotional settings and the social ambition of a larger architectural project.”

Snøhetta is an expensive studio, due to the emphasis on creative processes grounded in the business and work models. People are allowed to spend more time on conceptual work in initial phases. This is, in essence, what brings the prices up. “If we could get that in half, then we wouldn’t be expensive,” Informant 1 comments. “It is a fact here that everyone is allowed to spend a long time on developing a concept, on doing workshops …creating concepts and models. We allow that, which makes it more expensive…it’s not the fact that we have a huge overhead, it’s actually because we’re allowing people here to spend a lot more time”. These cost structures are also not well understood by clients in all countries. Informant 3 describes a situation outside of Norway in the following manner: “…we had one meeting with a client, …informant 2 told me that the client said, ‘Well you have no overview, or you always want to invoice, and now you’re here with three people. Why are you here with three people? One would have been enough, and then it’s not that many hours you need for the project.’ And then informant 2 said, ‘Yeah, but that’s how we work in Snøhetta. We take different people to have different perspectives on that. And that’s our creative process.’”

Recruitment

Success is essentially dependent on one of the P’s: people. Snøhetta is in the lucky position that many professionals would like to work for the organization. An important recruitment tool to identify suitable candidates for new openings is an expansive database of candidates. According to informant 4, Snøhetta looks for candidates with an ability to collaborate, and general receptiveness to the organisational culture and environment: “Everyone that comes to our team should feel that they get responsibility. They can flourish, show their talent, and we immediately give everyone much responsibility. As soon as you are on-board, you start collaborating with us. Your skills, your opinions, everything is important to us.” Part of the strategy is hiring young people “We want to educate them our self, to grow slowly, with quality.” The ambitions are to have a group consisting of “Experienced people together with young people, creating our culture.”

Recurrent methods are using the employee’s networks and internships, in the Oslo as well as the country office. Informant 7 does not believe these strategies are exceptional, although timing and luck may play a part “First, like everything in life, timing needs to be good. I was lucky because I did an internship while I was doing my diploma. When I delivered it, I was working already. I know that many people that were interns, the people in the company saw some potential in them and kept them tight”.

Others were introduced to Snøhetta while studying. Informant 5, a senior architect, met Kjetil and informant 2 while at university. Snøhetta’s conceptual approach and philosophy was what drew him in. Informant 6 had a similar experience “Snøhetta had a big exhibition in my school. At the Royal Academy (Copenhagen). One of our landscape architects was there to open the exhibition. Jenny. She was telling me about the way of working, about Snøhetta. I came up afterward to the studio space where I was working and told my fellow students that, ‘Right, I know now where I am going to be working after I’m done here.’” Informant 8, an intern in the country office, was third time lucky because there was an opening “I had made a submission based on an advert two times before. After my internship in another company and my Bachelor thesis, I had better chances, so I got an invitation for a talk, they needed someone to start very quickly; we need help; please come on Monday.”

The danger with this system, according to informant 1 is “…we all become a bit too similar; we don’t look at a broad enough portfolio of different people, skills, and ways of looking at things. It is very varying how we pick people, especially in the creative areas”. Informant 3’s take resonates “…many of the architects that work here used to study together. Many of them are actually from one class. I remember we talked about needing different people. Then I thought about how we hire people. I’m not sure we’ll get different people. It’s always the safe decision you make when you hire a person that you already know, or that you heard positive things about.” Informant 3 is clear that this system does work for the country office. It allows them to reach out to the right candidates more effectively than via a typical job advertisement “Take this model builder position we advertised for instance. First, we tried to put an ad online only…we had an impression that many of the applicants had no relationship to Snøhetta … We had many applications, but most of these people wanted to be architects. They just went for this model builder position because they wanted to work with Snøhetta.”

Remuneration and benefits, at least for architects, are according to a predetermined, transparent scale with progression dependent on seniority. Informant 7 seems to agree with the model. “This idea that you are part of a democratic system, you earn depending on seniority, how many years you have been working here” In his view, it has a conditioning effect on the work environment. People in Snøhetta are not there for the money or the positions. “That prevents clashes between people, fighting against each other in the hope of reaching better positions and pay. It depends on how long you work here, if you have worked here for 10 years you earn this amount of money.”

Informant 1 is more reserved. Partly because the set scale only applies for some of the employees, “I have never really been a fan of everybody telling what they earn because I do not think we are here for the money. The danger is that we keep everybody on a scale, and we say you’re not here for the money, and then we pay these people a lot and then they’re here for the money. The market for architects is pretty much on scale everywhere you go. For designers, it is like; you pay what you’re worth. It’s very different. Very market driven. It’s just a different way of doing business too.”

For informant 2, it is a balancing act “We have 40 paid effective working hours, in the main office in Oslo, they have 35 because they have 37 and a half hours, and a half hour lunch break, which is paid. Here the lunch break is not paid. It’s a balance. Some things we have to do legally. We don’t do precarious employment, everybody who works here has a contract, and of course, we have sensibly market-oriented salaries.”

Discussion and conclusion

As previously discussed, findings from a case study that is both single and singular, such as the one presented here, cannot in itself explain the behaviour of managerial shared leadership in a sector as broad as that of the cultural and creative industries. However, from its uniqueness, our explorations allow us to understand some of the logics at play, in particular when it comes to how a project that remains resilient over time, without direct public support, is able to survive periodic crises in the sector, and moves in diverse international environments. What Snøhetta has in common with other cultural projects, and what distinguishes it from organizations in other economic sectors, is the artisanal and collaborative character of the creative process, the ability to attract new talent to the organization based on the recognition and artistic uniqueness of the project, and the interaction with the client and the local community in which each project is located. Part of the success lies in the act of balancing aesthetic sensibility and commercial viability, also known as the difference paradox (DeFillippi et al., 2007), a recurring factor in most corporate cultural projects. All of these aspects are linked to the leadership model.

In this context, what makes Snøhetta a singular case, compared with other international companies in the creative economy, is the strong participatory and shared culture beyond the organisational leadership constellation. Further, the signature of the creative work is socialized: the outputs are credited collectively with the name of the firm instead of appearing with the names of the main creators. This fact contrasts with the dominant logic in the cultural and creative sector of highlighting the name of the main creative figures, despite the fact that most major projects are the result of the collective contribution of many creative people (Becker, 2008).

Initially, our case study of Snøhetta contemplated the following research questions. How can managerial shared leadership help strike a balance between the paradoxical institutional logics that management and leadership of creativity is premised upon? Is this constellation more resilient because they are considered more transparent, open, and generous?

Starting with the first, Snøhetta succeeds with the use of a particular kind of managerial shared leadership. At the top (Alvarez and Svejenova, 2005; Denis et al., 2012), the leadership constellation is distinguished by a division of labour between distinct yet interdependent roles for all intents and purposes. This is what the concept of managerial shared leadership refers to as functionally shared leadership (Döös and Wilhelmson, 2021). The leadership constellation for managing projects and teams is distributed among professionals in a way that varies with the complexity of the tasks at hand to promote adaptive problem-solving and forward momentum (Müller et al., 2018). The relationship between the approaches is that leadership becomes shared across units (projects, headquarters, and country office), and the model functions because of a set of values (the conceptual philosophy of the 3 p’s people, places, and projects) held in common (Döös and Wilhelmson, 2021).

In relation to the second question, does a balance premised on openness, transparency, and generosity make these constellations more resilient? The difference in employment conditions, social benefits, and business culture between studios and countries, as part of different legislative models, generates a perception of inequality with a short distance between the highest and lowest salaries and titles. The incorporation of a design division, with their concurrent, market-based salaries, increases the feeling that the horizontal model is failing. How may Snøhetta at once resolve the imbalances between international expansion and the social compatibility between offices? In particular, when professionals move from one office to another.

This is a concern related to the second foci in the literature on paradoxes: managing creative processes (DeFillippi et al., 2007). Here, Snøhetta succeeds due to the idiosyncratic way by which it enables exploration (providing opportunities for creative and inspirational work) and exploitation (making enough money to sustain the company’s expansive and expensive conceptual line of working) (Cohendet and Simon, 2007).

Snøhetta, a place, as well as a name is a conceptual and philosophical grounding of people taking part in projects. However, the resilience is in part due to processes of recruitment, ensuring that people who come to work for the company understand and are willing to adopt and engage in proprietary ways of conducting architecture business. This model—as it goes beyond a leadership constellation (Hodgson et al., 1965)—is shaped and formed by visionary entrepreneurs, is based on a Nordic approach to work, and has a generational spirit taking a holistic and collective approach to creativity, with emphasis on generosity and social responsibility. Essentially, as Kjetil argues, the “bottle” model requires freedom so that people are inspired to come together and manage to think as game-changers. This involves providing an environment wherein creative processes can flow through the collective, in other words, resolving the identity paradox of creating a collective identity and brand (DeFillippi et al., 2007) that leads to precise outputs as well as social outcomes, either in the form of products (the result of design processes and projects) or as places (in the case of architectonic processes and landscapes). All the offices try to maintain the key cultural and social values of the organization, but here again, the local dimension is necessary to consider.

This is something that attracts creative talent, and is an essential resource of any creative, since a collaborative leadership style influences the career paths of people and organizations. However, not everyone is prepared to work for a creative company where output is collectively credited (individual people do not sign off on designs and buildings) and under specific conditions (which includes a collective annual excursion to the Norwegian mountain of Snøhetta or a skiing day). That said, recruitment is not an issue; the studio receives far more applications from prospective candidates than they can process. There are many people interested in and fitting the personality and profile required to function as a creative within the organisational set-up.

Our findings demonstrate that creative workers are drawn to Snøhetta because the studio provides high-quality employment in an environment that puts more emphasis on symbolic value, knowledge sharing, and learning as opposed to financial gains. Without necessarily being in thrall of art-for-art’s sake motivation, there is a continuing match between their professional creative motives and the job opportunities (Lampel et al., 2000). For them, the ability to be part of the collective, the processes, and projects trumps financial motives. The cooperative spirit induces some of the creative employees to forfeit traditional benefits, such as individual recognition (stardom) and financial gain. The employees express similar attitudes to those of members of the art world when the discussion revolves around the collective production of designs and buildings (Becker, 2008). The fact that they are working for a commercial private enterprise that in many ways differs from publicly funded cultural institutions of the art world does not seem to matter. That is also the answer as to what characterises some of the most important success factors as they relate to managerial shared leadership: contextual antecedents (organisation and culture), alongside selection and appointment (Döös and Wilhelmson, 2021).

To conclude, this article has—through a case study of the international architectural studio Snøhetta—sought to show how it may be possible to resolve the potential conflicts caused by paradoxical logics of attending to the needs of creative workers (architects as artists and creative entrepreneurs) and the need for efficiency and practicality at the organisational level (Thornton et al., 2005) through managerial shared leadership constellations (Döös and Wilhelmson, 2021). Snøhetta achieves success by 1) fostering an atmosphere that encourages creative freedom and 2) addressing the organization’s need to continue operating profitably. (Cohendet and Simon, 2007). While there are issues and problems associated with translating constellations and horizontally shared practices across countries—a globalization paradox (DeFillippi et al., 2007)—the model is resilient because of a shared understanding of a common conceptual model and way of working (Döös and Wilhelmson, 2021).

Some literature on cultural leadership, notably those strands based on the visionary, charismatic approach often seen in the public sector institutions (Price, 2017), shows a need for management skills and structure when a private company seeks to control continuity and expansion. In line with Bolden (Bolden, 2004), it does not make sense to differentiate between the role of the leader and that of the manager, for specific ventures to succeed and grow. It is the dual capacity (ability to inspire and at the same time motivate) that is important. As Kjetil emphasized; motivation needs management, leadership needs inspiration.

In brief, the capacity to manage the process of symbol creation is a form of continuous innovation (Lawrence and Phillips, 2002). This may be some of the hallmarks of what make managerial shared leadership come together in this particular study of management and leadership of cultural organisations.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because Employee data has been anonymized. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AR: Concept development, literature review, data collection and initial analysis, writing LB: Concept development, data interpretation, analysis, writing.

Funding

The researchers received a grant from the Norwegian Ministry of Culture—Kunnskapsverket, with number reference 13/4343 and from the Research Council of Norway, grant number 301291.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Alvarez J. L. Svejenova S. (2005). Sharing executive power: roles and relationships at the top. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

2

Becker H. S. (2008). Art worlds: updated and expanded. Berkeley: University of California Press.

3

Bolden R. (2004). What is leadership? Exeter. United Kingdom: Centre for Leadership Studies, University of Exeter.

4

Bolden R. (2011). Distributed leadership in organizations: a review of theory and research. Int. J. Manag. Rev.13 (3), 251–269. 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00306.x

5

Bolden R. Hawkins B. Gosling J. (2011). Exploring leadership. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

6

Bonet L. Donato F. (2011). The financial crisis and its impact on the current models of governance and management of the cultural sector in Europe. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy1 (1), 4–11. 10.3389/ejcmp.2023.v1iss1-article-1

7

Bonet L. Négrier E. (2018). The participative turn in cultural policy: paradigms, models, contexts. Poetics66 (66), 64–73. 10.1016/j.poetic.2018.02.006

8

Burns S. Wilson K. (2010). “Trends in leadership writing and research: a short review of the leadership literature,” in A cultural leadership reader. Editors Kay,S.VennerK. (Manchester, UK: Arts Council England), 86–95.

9

Byrnes W. Brkić A. (2019). The routledge companion to arts management. United Kingdom: Routledge.

10

Cohendet P. Simon L. (2007). Playing across the playground: paradoxes of knowledge creation in the videogame firm. J. Organ. Behav.28 (5), 587–605. 10.1002/job.460

11

DeFillippi R. Grabher G. Jones C. (2007). Introduction to paradoxes of creativity: managerial and organizational challenges in the cultural economy. J. Organ. Behav.28 (5), 511–521. 10.1002/job.466

12

DeFillippi R. J. Arthur M. B. (1998). Paradox in project-based enterprise: the case of film making. Calif. Manag. Rev.40 (2), 125–139. 10.2307/41165936

13

Denis J.-L. Langley A. Sergi V. (2012). Leadership in the plural. Acad. Manag. Ann.6 (1), 211–283. 10.5465/19416520.2012.667612

14

DiMaggio P. (1982). Cultural entrepreneurship in nineteenth-century Boston: the creation of an organizational base for high culture in America. Media, Cult. Soc.4 (1), 33–50. 10.1177/016344378200400104

15

DiMaggio P. J. Powell W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev.48, 147–160. 10.2307/2095101

16

Döös M. Wilhelmson L. (2021). Fifty-five years of managerial shared leadership research: a review of an empirical field. Leadership17 (6), 715–746. 10.1177/17427150211037809

17

Ebbers J. J. Wijnberg N. M. (2012). Nascent ventures competing for start-up capital: matching reputations and investors. J. Bus. Ventur.27 (3), 372–384. 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.02.001

18

Ebbers J. J. Wijnberg N. M. (2017). Betwixt and between: role conflict, role ambiguity and role definition in project-based dual-leadership structures. Hum. Relat.70 (11), 1342–1365. 10.1177/0018726717692852

19

Eikhof D. R. Haunschild A. (2007). For art's sake! Artistic and economic logics in creative production. J. Organ. Behav.28 (5), 523–538. 10.1002/job.462

20

Eldh A. C. Årestedt L. Berterö C. (2020). Quotations in qualitative studies: reflections on constituents, custom, and purpose. Int. J. Qual. Methods19, 160940692096926. 10.1177/1609406920969268

21

Fjellvaer H. (2010). Dual and unitary leadership: managing ambiguity in pluralistic organizations. Bergen: Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration.

22

Flyvbjerg B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual. Inq.12 (2), 219–245. 10.1177/1077800405284363

23

Flyvbjerg B. (2011), “Case study,” in The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Editors Denzin,N. K.LincolnY. S. (California: Thousand Oaks). 301–316.

24

Gann D. M. Salter A. J. (2000). Innovation in project-based, service-enhanced firms: the construction of complex products and systems. Res. policy29 (7-8), 955–972. 10.1016/s0048-7333(00)00114-1

25

Gibeau É. Reid W. Langley A. (2016). “Co-Leadership: contexts, congurations and conditions,” in The Routledge companion to leadership. Editors StoreyJ.HartleyJ.DenisJ.-L.Hartt' P.UlrichD. (London: Routledge), 247–262.

26

Gilson L. L. (2015). “Creativity in teams: processes and outcomes in creative industries,” in The oxford handbook of creative industries. Editors JonesC.LorenzenM.SapsedJ. (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press), 50–74.

27

Grabher G. (2002). Cool projects, boring institutions: temporary collaboration in social context. Reg. Stud.36 (3), 205–214. 10.1080/00343400220122025

28

Herzog C. Handke C. Hitters E. (2019). “Analyzing talk and text II: thematic analysis,” in The palgrave handbook of methods for media policy research. Editors Van den BulckH.PuppisM.DondersK.Van AudenhoveL. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 385–401.

29

Hodgson R. C. Levinson D. J. Zaleznik A. (1965). The executive role constellation: an analysis of personality and role relations in management. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

30

King I. W. Schramme A. (2019). “Introduction to the project,” in Cultural governance in a global context: an international perspective on art organizations. Editors King,I. W.SchrammeA. (Cham: Springer), 1–20.

31

Kotter J. P. (1996). Leading change. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press.

32

Lampel J. Lant T. Shamsie J. (2000). Balancing act: learning from organizing practices in cultural industries. Organ. Sci.11 (3), 263–269. 10.1287/orsc.11.3.263.12503

33

Lawrence T. B. Phillips N. (2002). Understanding cultural industries. J. Manag. Inq.11 (4), 430–441. 10.1177/1056492602238852

34

Mandel B. (2017). Arts/cultural management in international contexts. Hildesheim: Universitätsverlag Hildesheim.

35

Mintzberg H. (1973). The nature of managerial work. Engelwood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

36

Müller R. Sankaran S. Drouin N. Vaagaasar A.-L. Bekker M. C. Jain K. (2018). A theory framework for balancing vertical and horizontal leadership in projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag.36 (1), 83–94. 10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.07.003

37

Nisbett M. Walmsley B. (2016). The romanticization of charismatic leadership in the arts. J. Arts Manag. Law, Soc.46 (1), 2–12. 10.1080/10632921.2015.1131218

38

Noble H. Smith J. (2015). Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evid. Based Nurs.18 (2), 34–35. 10.1136/eb-2015-102054

39

Pan S. L. Tan B. (2011). Demystifying case research: a structured–pragmatic–situational (SPS) approach to conducting case studies. Inf. Organ.21 (3), 161–176. 10.1016/j.infoandorg.2011.07.001

40

Pearce C. L. (2004). The future of leadership: combining vertical and shared leadership to transform knowledge work. Acad. Manag. Perspect.18 (1), 47–57. 10.5465/ame.2004.12690298

41

Pearce C. L. Conger J. A. (2003). “All those years ago.: the historical underpinnings of shared leadership,” in Reframing the hows and whys of leadership. Editors PearceC. L.CongerJ. A. (Sage Publications), 1–18.

42

Peltoniemi M. (2015). Cultural industries: product–market characteristics, management challenges and industry dynamics. Int. J. Manag. Rev.17 (1), 41–68. 10.1111/ijmr.12036

43

Peterson R. A. (1986). “From impresario to arts administrator: formal accountability in non-profit art organisations,” in Non-profit enterprise in the arts: studies in mission and cosntraint. Editor DiMaggioP. (New York: Oxford University Press), 161–184.

44

Price J. (2017). The construction of cultural leadership. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy7 (1), 5–16. 10.3389/ejcmp.2023.v7iss1-article-1

45

Reid W. Fjellvær H. (2022). Co-Leadership in the arts and culture: sharing values and vision. London: Taylor & Francis.

46

Reid W. Karambayya R. (2009). Impact of dual executive leadership dynamics in creative organizations. Hum. Relat.62 (7), 1073–1112. 10.1177/0018726709335539

47

Reid W. Karambayya R. (2016). The shadow of history: situated dynamics of trust in dual executive leadership. Leadership12 (5), 609–631.

48

Rosing K. Zacher H. (2023). “Ambidextrous leadership: a review of theoretical developments and empirical evidence,” in Handbook of organizational creativity Editors Reiter-Palmon,RHunterS2nd ed. (United States: Academic Press), 51–70.

49

Royseng S. (2008). Arts management and the autonomy of art. Int. J. Cult. policy14 (1), 37–48. 10.1080/10286630701856484

50

Sergi V. Denis J.-L. Langley A. (2017). “Beyond the hero-leader: leadership by collectives,” in The routledge companion to leadership. Editors StoreyJ.HartleyJ.DenisJ.-L.‘t HartP.UlrichD. (Abingdon: Routledge), 35–51.

51

Spillane J. P. Diamond J. B. (2007). Distributed leadership in practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

52

Sutherland I. Gosling J. (2010). Cultural leadership: mobilizing culture from affordances to dwelling. J. Arts Manag. Law, Soc.40 (1), 6–26. 10.1080/10632921003603984

53

Thornton P. H. Jones C. Kury K. (2005). “Institutional logics and institutional change in organizations: transformation in accounting, architecture, and publishing,” in Transformation in cultural industries. (United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 125–170.

54

Thornton P. H. Ocasio W. (2008). “Institutional logics,” in The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism. 840. Editors GreenwoodR.OliverC.SahlinK.SuddabyR. (London: Sage), 99–128.

55

Yin R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications. 6th ed.London: Sage publications.

56

Zhu J. Liao Z. Yam K. C. Johnson R. E. (2018). Shared leadership: a state‐of‐the‐art review and future research agenda. J. Organ. Behav.39 (7), 834–852.

Summary

Keywords

plural leadership, creative entrepreneurship, creative leadership, international studio, architecture and design

Citation

Bonet L and Rykkja A (2023) Why is managerial shared leadership in creative organizations a more resilient, transparent, open, and generous constellation? A case analysis approach. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 13:12056. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2023.12056

Received

15 September 2023

Accepted

05 December 2023

Published

18 December 2023

Volume

13 - 2023

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Bonet and Rykkja.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lluis Bonet, lbonet@ub.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.